CHAPTER 3

THE CIRCULARITY OBJECTION

INTRODUCTION

In the previous chapter, several arguments were considered which purport to prove that counterfactuals of creaturely freedom cannot be true. In this chapter, a different but related argument that attacks the usefulness of middle knowledge for God’s creative decision will be examined. It may be properly seen as an extension of the grounding objection, though it is typically treated separately. This argument focuses on the steps in the divine deliberative process regarding God’s creative work.

COUNTERFACTUALS OF FREEDOM, TRUTH, AND SIMILARITY AMONG WORLDS

Vicious Circle Argument

The first version of this argument was apparently discovered independently by Anthony Kenny and Robert Adams, who both complain that the possible worlds explanation for the truth of counterfactuals leads to a vicious circle. They point out that Molinism requires counterfactuals of creaturely freedom to be true logically prior to God’s decision to create, since they are thought to inform that creative decision. However, they argue that a problem exists because the relevant counterfactuals do not at that time have a truth value or are false, and therefore cannot be known.1 Kenny writes, “But prior to God’s decision to actualize a particular world those counterfactuals cannot yet be known: for their truth-value depends, on Plantinga’s own showing, on which world is the actual world.”2 Adams concurs: “On the possible worlds theory, moreover, the truth of the crucial conditionals cannot be settled soon enough to be of use to God.”3 Kenny correctly notes that this objection rests on the belief that counterfactuals are true due to the similarity of the possible world in which they hold to the actual world and proceeds from there. Simply put, which world is actual cannot be determined until God makes his creative decision, and that decision cannot be made until the counterfactuals are known.4 In order to see this more clearly, consider an example supplied by Adams. He invites us to consider a proposition that God presumably knew prior to his decision to create:

If God were to create Adam and Eve, there would be more moral good than moral evil in the history of the world.

God uses his middle knowledge of propositions like this to aid his decision regarding which possible world to actualize. More generally, God considers propositions—what Adams calls deliberative conditionals—of the form, “If I did x, y would happen,” in determining which possible world to create/actualize. Adams argues that the truth of these kinds of statements cannot be determined prior to the actual world being actualized because it “depends on whether the actual world is more similar to some world in which I do x and y happens than to any world in which I do x and y does not happen.”5 The problem is that similarity to the actual world depends on which possible world is actual, which in turn depends in part on whether Adams does x. He concludes that the truth of the proposition regarding relative moral good and evil if God were to create Adam and Eve “will depend on whether God creates Adam and Eve.”6

This argument is really twofold. It rests on the premise that there is an interdependent relationship among the steps in the divine deliberative process regarding creation, and that counterfactuals cannot be true soon enough to be of use to God in his decision regarding creation. These two claims are tied together, but for purposes of analysis, will be treated separately.

First, both Adams and Kenny claim that an interdependent relationship exists between the similarity relation among possible worlds and the truth of counterfactuals. This interdependence seems to lead to a vicious circle; the truth of any given counterfactual in the actual world depends on its truth in the possible-but-not-actual world that is closest to it, but the possible-but-not-actual world that is closest to the actual world is the one which shares counterfactuals with the actual world, and so their truth must be determined prior to the establishment of similarity. This may be made more clear if an example is set forth.

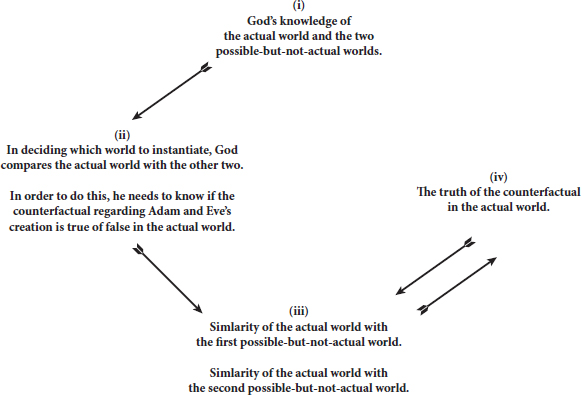

Suppose, with Adams, that it is true that the world would be a better place if God were to create Adam and Eve, and God used his knowledge of this in determining which possible world to actualize. Now consider two possible-but-not-actual worlds that are exactly alike, except that in the first, the counterfactual, If God were to create Adam and Eve, there would be more moral good than moral evil in the history of the world, is true, and in the second, it is false. In this case, Adams argues, the counterfactual is true in the actual world if the actual world is more similar to the first possible-but-not-actual world than to the second, but the closeness of either of the two worlds (to the actual world) cannot be established until the truth of the counterfactuals in the actual world is set (which, of course, only occurs at the moment God decides to actualize a particular world or at the moment he actualizes a world). The argument may be diagramed as follows, and the circular nature of Molinism is clear:

Figure 1

Second, this argument claims that middle knowledge cannot serve the purpose Molina’s system requires because counterfactuals are not true soon enough to inform God’s creative decision. According to Kenny and Adams, God’s decision about which world to actualize requires information only available after he has made his decision about which world to actualize. In other words, a world must be actualized prior to the counterfactuals in that world being true, but the counterfactuals supposedly influence his decision about which world to actualize. An example may clarify the argument.

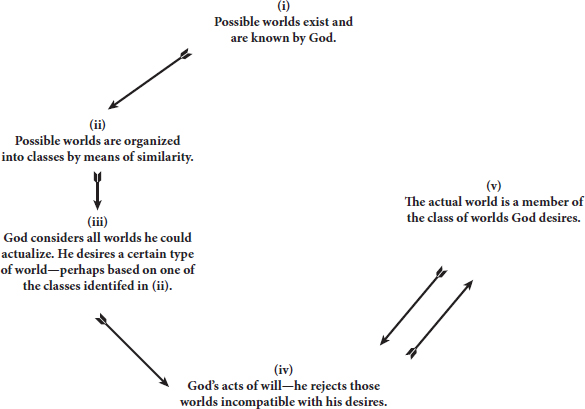

Assume again that God considered truths such as the aforementioned counterfactual and that he desires a world containing more moral good than moral evil. It follows that the counterfactual (If God were to create Adam and Eve, there would be more moral good than moral evil in the world) is true in the actual world. Adams invites the reader to entertain the idea that there is a whole set of worlds that are more similar to a possible-but-not-actual world in which God creates Adam and Eve and there is more moral good than moral evil in the history of the world, than to a second possible-but-not-actual world where God creates Adam and Eve and there is not more moral good than moral evil in the history of the world. Adams maintains that Molinism requires that God compared the worlds of the set with the two possible-but-not-actual worlds in order to aid his decision regarding which world to actualize, and argues that the truth of the counterfactual in the actual world depends on the actual world being a member of that set, but such membership cannot have been established prior to God’s decision to actualize the world he did. He claims that this can be seen once we consider another kind of world God could have considered actualizing, a world in which there are no free creatures. Since morality and responsibility are strongly tied to individual freedom (an assumption granted by most Molinists, but not beyond challenge), there seems to be no way to speak of moral good and moral evil in a world where there are no free creatures. If this is the case, then there is no way to determine if it is more similar to the former or latter worlds, and it cannot be a member of the class of worlds considered. In other words, the decision of which world to actualize depends on the worlds’ being a member of the desired set, but the world’s membership in the set depends on its similarity to the correct possible-but-not-actual world. Some may think that a world containing no free will would result in agnosticism regarding that world’s membership in the set. Such a conclusion, though, would be based on the mistaken notion that the complement of the desired counterfactual, If God were to create Adam and Eve, there would be more moral good than moral evil in the history of the world; is If God were to create Adam and Eve, there would be more moral evil than moral good in the history of the world; and the truth of both of these is indeterminate in such a world. However, the complement of the desired counterfactual is, in actuality, the following: If God were to create Adam and Eve, there would not be more moral good than moral evil in the history of the world. This counterfactual would be true in the second possible-but-not-actual world considered, and it would also be true in a world containing no free creatures, for if moral good and moral evil depend on creaturely freedom, then a world which contains no free creatures will have an equal amount of moral good and moral evil, namely none. Adams’ argument may be diagramed as follows:

Figure 2

Molinist Responses

At least three responses to this objection are available to the Molinist: 1) deny the use of possible worlds semantics, 2) identify specific flaws in wording or logic in the argument, or 3) clarify misunderstandings of the possible worlds analysis of counterfactuals. All three approaches have been used by Molinists, and each will be briefly examined.

Possible worlds semantics

The argument presented by Adams and Kenny is clearly dependent upon the Stalnaker-Lewis approach to counterfactual analysis. Recall that according to this approach, a counterfactual is true in the actual world if and only if it is true in the possible-but-not-actual world that is most similar to the actual world. Yet, according to Adams and Kenny, similarity cannot be determined until the truth of counterfactuals is known and the truth of counterfactuals cannot be determined until the similarity of worlds is established. As already noted, not all Molinists accept the Stalnaker-Lewis thesis as an adequate explanation of counterfactual logic. If the relation between similarity of worlds and truth is denied, then the objection loses its force.

Logical/wording flaws

Alvin Plantinga has criticized this argument at the point of the depends on relation. He notes that the concept of depends on must be transitive for the argument to work, but it is not. In order to illustrate his point, he invites the reader to consider an argument which utilizes the same terminology, but is clearly false because of an equivocation in the meaning of “depends on.” Consider the proposition, “The truth of The Allies won the Second World War depends on which world is actual.” This should be clear enough, for presumably there is some possible-but-not-actual world where the Allies did not win WWII. Now consider a similar statement, but future-directed: “Which world is actual depends on whether I mow my lawn this afternoon.” Plantinga claims that, following similar logic to that employed by Adams, it should follow that “The truth of The Allies won the Second World War depends on whether I mow my lawn this afternoon.”7

Linda Zagzebski has argued that Plantinga’s response to Adams—that the depends on relation between which world is actual and an individual’s action is not transitive—misses the point, and that the depends on relation need only be asymmetrical. However, her counterexamples and reframing of the circularity objection is not convincing.8

Clarification of possible worlds analysis

Probably the most striking problem with the argument presented by Kenny and Adams is that it makes some assumptions about the possible worlds semantics which are not correct. Plantinga correctly notes that underlying this objection is the false assumption that similarity among worlds somehow causes or grounds the truth of counterfactuals, but this is not how the similarity relation functions in counterfactual logic. Instead, similarity of possible worlds only shows what it means for counterfactuals to be true. Plantinga writes:

In the same way we can’t sensibly explain necessity as truth in all possible worlds; nor can we say that p’s being true in all possible worlds in [sic] what makes p necessary. It may still be extremely useful to note the equivalence of p is necessary and p is true in all possible worlds: it is useful in the way diagrams and definitions are in mathematics; it enables us to see connections, entertain propositions and resolve questions that could otherwise be seen, entertained and resolved only with the greatest difficulty if at all.9

Since similarity among worlds is not what causes counterfactuals to be true, the move from (iv) to (v) in the argument is denied. Rather, (v) is really part of (i). The counterfactuals that are true in the actual world are true prior to God’s consideration of the possible worlds; it is part of what God considers. Prior to God’s decision to create (and creating!) the actual world is just one among the virtually infinite number of possible worlds being considered. The closest possible-but-not-actual world is only revealed once God creates (as are all possible-but-not-actual worlds because prior to God’s creating, they are all merely possible worlds). Relative similarity to the actual world is a function of God’s creation decision.10

Some Molinists have argued that the actualization of the actual world is progressive and that this removes the force of the objection. For example, William Lane Craig writes, “What this objection fails to appreciate is that parallel to the logical sequence in God’s knowledge—natural knowledge, middle knowledge, free knowledge—there is a logical sequence in the instantiation of the actual world as well.”11 Craig argues that it is incorrect to speak of God’s actualizing an entire possible world at the first logical moment—God’s natural knowledge—though it is true that some aspects of the actual world obtain. At the second logical moment of divine deliberation (middle knowledge), more aspects of the actual world obtain. According to Craig, it is at this moment that “all those states of affairs corresponding to true counterfactuals of creaturely freedom obtain.”12 For example, the state of affairs, If Adam were offered the forbidden fruit, he would eat, obtains. At this point, of course, Adam does not exist and God could decide to refrain from creating/instantiating him. It is not until the third logical moment of divine deliberation that the actual world is instantiated by an act of divine will. According to Craig, the force of the not soon enough objection has been removed because the premise behind it, namely that counterfactuals must be true before the actual world obtains, has been shown to be false. He writes:

The upshot of this is that it is not wholly correct to say with Kenny that prior to the divine decree the actual world does not obtain, for certain aspects of it do and other aspects do not. And those states of affairs that do obtain are sufficient for the truth of counterfactuals of creaturely freedom, since the latter correspond with reality as it thus far exists and since possible worlds can be ranked in their similarity to the actual world as thus far instantiated, thus supplying the truth conditions for a possible worlds analysis of the truth of counterfactuals of freedom in terms of degree of shared counterfactuals. Once it is appreciated that there is a logical sequence in the exemplification of the actual world just as much as there is in God’s knowledge, then objections to middle knowledge based on counterfactuals’ being true "too late" to facilitate such knowledge disappear.13

Hasker complains that these answers skirt the force of the objection and return to the grounding objection. He writes, “So we are confronted with this vast array of counterfactuals—probably thousands or even millions for each actual or possible free creature—almost all of which simply are true without any expectation whatever of this fact being given. Is this not a deeply puzzling, even baffling state of affairs?”14 Hasker is correct to note the close ties between the priority objections and the grounding objections. In fact, it appears that the priority objections reduce down to the grounding objection. Therefore, if an acceptable answer to the grounding objection can be presented, all obstacles to middle knowledge will be removed.

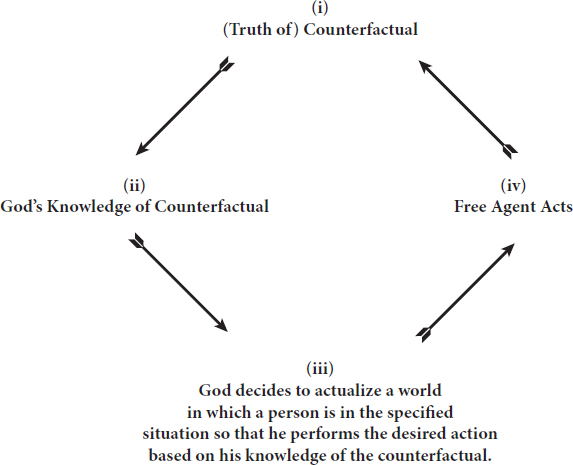

EXPLANATORY PRIORITY, CIRCULARITY, AND DETERMINISM

The second version of this argument has been developed by Robert Adams.15 Recall that Molinism is based upon the premise that there are several logical steps in God’s decision process regarding creation: Necessary truths are logically prior to God’s knowledge of counterfactuals of freedom, and the truth values of those counterfactuals are prior to God’s knowledge of them. God uses his knowledge of the necessary truths and the true counterfactuals of creaturely freedom in order to decide which possible world to actualize so that he gets what he desires. Flint has characterized Adams’ argument as making the claim that the libertarian nature of a person’s action requires that it (i.e., the action) be logically prior to the truth of the relevant counterfactual of creaturely freedom about that action.16 If this is indeed the argument that Adams is advocating and if he is correct, then the circular nature of the Molinist account of divine foreknowledge and providence, and its viciousness, is readily apparent. It may be diagrammed as follows:

Figure 3

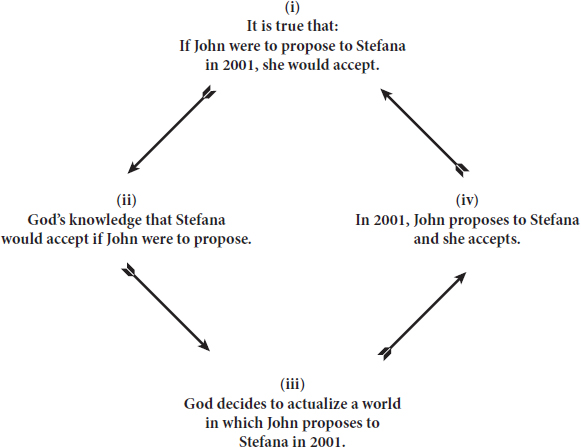

Perhaps an example of a deliberative conditional (colloquially, counterfactual of creaturely freedom) known to be true will make the argument more clear. I proposed to Stefana in August, 2001, and she accepted. Thus, the counterfactual, If John were to propose to Stefana in August, 2001, she would freely accept; is known to be true, and presumably this information was known to God prior to his decision to actualize any world and it informed/influenced his decision to actualize this world. In other words, God wanted Stefana and I to marry, and he actualized a world in which we would be in a situation where I propose in 2001.17 Thus, the counterfactual was true logically prior to God’s decision about which world to actualize, and prior to any action on my part or on Stefana’s part. Yet this characterization of the argument has Adams claiming that it is precisely Stefana’s action of accepting my proposal that makes the counterfactual true. Thus, our actions—my proposal and her free acceptance—must be prior to the truth of the relevant counterfactuals and the Molinist system is shown to be circular and therefore, fails.

Figure 4

Flint recognizes that this characterization of the argument includes a step that Adams did not make, namely the move from Stefana’s acceptance back to the establishment of the counterfactual, but this move is clearly false according to Molinism. The doctrine of middle knowledge does not require that an action be performed in order for propositions describing that action to be true, but this is precisely the picture of Molinism described. The problem with this interpretation may be seen if a deliberative conditional that is not known to be true is considered. For example, the counterfactual, If Pius XII had intervened, Hitler would have stopped the deportation of the Jews of Rome to Auschwitz; may be true, but there is no way for us to know it. Adams seems to hold that Molinism must assert that the counterfactual is false because Pius XII did not intervene. However, Molinism clearly does not lead to this conclusion; in fact, it is based on the claim that conditionals such as this can be true! Herein lies the problem:

The interesting thing to note about this diagram is that it describes some events which actually occurred. Pius XII did not intervene, and the Jews of Rome were in fact deported, but this does not mean that the counterfactual describing what Hitler would have done had Pius XII intervened is false. In fact, Cornwell believes that it is true, and there is no reason for the Molinist to think him incorrect; there is nothing inherent in the doctrine of middle knowledge that requires the counterfactual to be false due to the events which have actually occurred.18 Surely this is not the argument Adams presents. Instead, he contends that the free nature of Pius XII’s action precludes there being a truth about what he would have done or would do because its being true means that he could not have done otherwise. Put differently, Adams says that counterfactuals are true prior to the action, which renders the course of action certain, but this is contrary to the individual named in the counterfactual having the ability to do otherwise, and therefore, Molinism violates libertarian freedom.

While I have attempted to avoid long, protracted arguments with enumerated propositions, I have deemed it necessary to set forth Adams’ argument as he originally presented it.19 This will enable the reader to understand the rather detailed responses by Molinists. Adams’ argument proceeds:

(1) According to Molinism, the truth of all true counterfactuals of freedom about us is explanatorily prior to God’s decision to create us.

(2) God’s decision to create us is explanatorily prior to our existence.

(3) Our existence is explanatorily prior to all of our choices and actions.

(4) The relation of explanatory priority is transitive.

(5) Therefore it follows from Molinism (by 1–4) that the truth of all true counterfactuals of freedom about us is explanatorily prior to all of our choices and actions.

(6) It follows also from Molinism that if I freely do action A in circumstances C, then there is a true counterfactual of freedom F*, which says that if I were in C, then I would (freely) do A.

(7) Therefore it follows from Molinism that if I freely do A in C, the truth of F* is explanatorily prior to my choosing and acting as I do in C.

(8) If I freely do A in C, no truth that is strictly inconsistent with my refraining from A in C is explanatorily prior to my choosing and acting as I do in C.

(9) The truth of F* (which says that if I were in C, then I would do A) is strictly inconsistent with my refraining from A in C.

(10) If Molinism is true, then if I freely do A in C, F* both is (by 6) and is not (by 7–8) explanatorily prior to my choosing and acting as I do in C.

(11) Therefore (by 9) if Molinism is true, then I do not freely do A in C.

As should be clear, this critique is similar in nature to Hasker’s counterfactuals as part of the causal history of the world argument.

Molinist Responses

The most obvious response to Adams’ argument here is akin to some offered for the grounding objection. Adams seems to have begged the question of incompatibilism regarding libertarian free will and true counterfactuals of freedom. But this response can seem dismissive, so more should be said. Fortunately, Molinists have offered other answers.

Craig argues that Adams has equivocated in his use of “explanatory priority”; it functions in a different way in (1) from how it functions in (2) and (3). In (2) and (3), explanatory priority seems to refer to the relationship between consequent and condition. Craig illustrates this point by rewording (2) and (3) in order to bring this aspect out:

(2a) If God has not created us, we should not exist;

(3a) If we were not to exist, we should not make any of our choices and actions.

A moment’s reflection will show that this will not work for (1) because

(1a) According to Molinism, if all true counterfactuals of freedom about us were not true, God would not have decided to create us.

is false. It seems abundantly clear that God may have chosen to create me, even if some counterfactuals about me had been different. This is made especially clear when a counterfactual which has no bearing (so far as I can tell) on the history of the world is considered. The counterfactual, If John were offered $100,000,000 with no strings attached, he would accept; is most likely true in the actual world. I do not know it is true, but I do have a high degree of confidence in its truth. At the same time, though, I also feel quite certain that a world where I am offered $100,000,000 with no strings attached is quite distant; I do not foresee any such offers coming my way. If I am correct in this supposition, then it does not seem likely that the counterfactual describing my response to such an offer played a significant role in God’s creation decision. What if I really do not know myself as well as I think, and instead, it is true that I would not accept the offer of $100,000,000, even if no strings were attached? What if I am not as worldly as I am inclined to think I am? It does not appear that anything significant follows; this difference would not seem to change anything in God’s creative decision, all other things being equal. It follows that, even if the counterfactuals about the creatures God instantiated were different than they in fact are, God still may have chosen to instantiate them. In fact, it seems that there could have been a great many counterfactuals that were different, and God’s choice would have remained the same because they would have no impact on the history of the world. Craig believes that the error in Adams’ argument is a confusion of reasons and causes. He writes, “Adams’s mistake seems to be that he leaps from God’s decision in the hierarchy of reasons to God’s decision in the hierarchy of causes and by this equivocation tries to make counterfactuals of creaturely freedom explanatorily prior to our free choices.”20

Flint has also charged Adams with equivocation in his use of explanatory priority. The key points in Adams’ argument, according to Flint, are (1), (2), (3), (4), and (8). Flint notes that Adams seems to imply that explanatory priority should be understood in terms of causal power.21 However, he contends that this understanding of explanatory priority will work for points (1), (2), (3), and (4), but not for (8) because it compromises the doctrine of divine foreknowledge. Thus, a causal analysis of explanatory priority will not work. This is similar to the point made earlier about begging the question.

Next, Flint asks whether explanatory priority can be understood in terms of counterfactual power, and it fares no better.22 It does not work in (4) because the counterfactual relation is not transitive. If it were, then the upshot of Adams’ argument would be that no matter what the individual named in a counterfactual does, the counterfactual will say what it does. This only follows if Adams presupposes that persons do not have counterfactual power over the past. This will be discussed more in the next chapter, but suffice it to say that most Molinists believe that persons have the power to act in such a way that past truths about their free actions would have been different from how they, in fact, were. Thus, Flint concludes that there is no reason for the Molinist to accept the second conjunct of (9).

Flint then considers several other proposals that may serve as definitions of explanatory priority for use in Adams’ argument, but demonstrates that none are satisfactory.23 He concludes that it is doubtful any such definition can be given.24 Thus, he has given the problem back to the detractor of Molinism, but it must also be admitted that no proponents of Molinism have provided an alternate definition or proven that one cannot be given which will work in the argument. In fact, proponents of Molinism must concede that the system employs a conception of priority and that therefore, this problem is one that will continue to be raised by opponents.25

CONCLUSION

In this chapter, I have presented a critique of the doctrine of middle knowledge which purports to show that the logical moments in the divine deliberative process required by the Molinist system are incoherent. Two separate, yet closely related versions of the argument were examined, and each was found wanting.

The first version of the argument, offered by both Adams and Kenny, criticizes the possible worlds approach to understanding the truth of counterfactuals. They have argued that the truth of counterfactuals in the actual world is dependent upon which possible-but-not-actual world is closest to the actual world, and which counterfactuals are true in it. However, the closest possible-but-not-actual world to the actual world cannot be determined until the actual world is identified. This fact leads Adams and Kenny to conclude that Molinism is viciously circular. They proclaim that counterfactuals cannot serve the purpose the doctrine of middle knowledge requires of them because counterfactuals are not true soon enough to be of use to God in his decision about which possible world to actualize.

I noted that this version of the priority objection relies upon the Molinist acceptance of the Stalnaker-Lewis approach to understanding the truth of counterfactuals. This approach, however, is not inherent in the Molinist system, is not accepted by all Molinists, and has been misconstrued by Adams and Kenny as a causal relationship. The Stalnaker–Lewis approach to the truth of counterfactuals by way of comparative similarity among possible worlds is only meant to be an explanatory tool regarding what it means to say counterfactuals are true much in the same way that truth in all possible worlds is meant to aid in conceiving of the concept of necessary truth. Similarity among worlds does not make or cause counterfactuals to be true.

I also pointed out that this version of the argument assumes that the truth of counterfactuals is grounded in the similarity relation among possible worlds. This answer to the grounding objection, however, was considered and rejected in the previous chapter. Grounding the truth of propositions which hold in the actual world in the occurrence of events in a non-actual world does not seem to be the best solution to the grounding objection. Thus, if a different answer to the grounding objection can be presented, then the vicious circle argument fails.

The second version of the argument has been set forth by Robert Adams and relies heavily upon the concept of explanatory priority. According to Adams, since Molinism requires that counterfactuals of creaturely freedom be true (explanatorily) prior to the existence of the individuals to whom they refer and, hence, prior to the actions they describe, then the freedom of the creatures is removed with respect to the actions described. This loss of freedom is due to the fact that if the counterfactual is true prior to the action, then the individual does not have the power to do otherwise (because if the individual was to do otherwise, the counterfactual would have been false).

It was argued that Adams has made two fatal errors in his critique. First, he has begged the question of the compatibility of truths about future or non-actual actions, and those actions being free. Second, he has equivocated in his use of explanatory priority. An interpretation of explanatory priority in terms of causal power presupposes that divine foreknowledge is incompatible with human freedom. An interpretation of explanatory priority in terms of counterfactual power fares no better because it either presupposes that counterfactuals are false (which is what Adams hopes to prove), or it presupposes that the agent named in the counterfactual does not have counterfactual power over the truth of the counterfactual (which is also what Adams hopes to prove). Either way, the argument is suspect because it ends up begging the question. The problem has been handed back to the detractor of Molinism—a satisfactory definition of explanatory priority must be given if the argument is to succeed. Since no such definition has been offered, the second version of the priority objection fails as well.

1. It seems that both Kenny and Adams originally maintained that counterfactuals do not have a truth-value, though Adams changed his position to make the claim that they are all false (at least, counterfactuals of creaturely freedom). See the reprint of his “Middle Knowledge and the Problem of Evil,” in The Virtue of Faith (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), 91, n. 4. He seems to have changed his position due in large part to interaction with Alvin Plantinga, who has pointed out the strangeness of saying propositions do not have a truth value. As Plantinga writes, “But how could a proposition fail to have a truth value? Either things are as it claims they are, in which case it is true, or it’s not the case that things are thus, in which case it is false.” Plantinga, “Replies,” 373. On either count, the argument can proceed. What is relevant is the claim that prior to creating, counterfactuals of creaturely freedom cannot be true.

2. Anthony Kenny, The God of the Philosophers (Oxford: Clarendon, 1979), 70.

3. Adams, “Middle Knowledge and the Problem of Evil,” 109–17.

4. Kenny writes, “The problem is that what makes the counterfactual true is not yet there at any stage at which it is undecided which world is the actual world. The very truth-conditions which the possible-world semantics were introduced to supply are absent under the hypothesis that it is undetermined which world the actual world is to be. But if truth-conditions are not fulfilled, the propositions are not true; and if they are not true not even an omniscient being can know them.” Kenny, The God of the Philosophers, 70.

5. Adams, “Middle Knowledge and the Problem of Evil,” 113.

6. Ibid., 114.

7. Plantinga, “Replies,” 376.

8. For a more thorough discussion of Zagzebski’s response to Plantinga and her development of the circularity objection, see my “Molinism and Supercomprehension,” 260–65.

9. Plantinga, “Replies,” 378.

10. All that must be established is that the world to be actualized is one of a particular set, or class, of worlds. Recall the discussion of feasibility in chapter 1. The counterfactual regarding the relative amount of moral good if God were to create Adam and Eve may be true in all worlds God could actualize (that is, in all feasible worlds) and therefore, which specific world is actual does not have to be settled in order for it to be true in the actual world. In other words, the counterfactual may be true in all the possible worlds of a given set and since God only actualizes a world-germ, he does not need to know which world is actual to make his creative decision.

11. Craig, “Hasker on Divine Knowledge,” 102.

12. Craig, Divine Foreknowledge and Human Freedom, 266.

13. Ibid., 267.

14. Hasker, God, Time, and Knowledge, 38.

15. See Adams, “An Anti-Molinist Argument,” 343–53.

16. Flint, Divine Providence, 159–62.

17. This is, admittedly, simplistic. After all, it may be that God did not desire a world where Stefana and I marry (though I doubt it), and instead this world met his other desires better than any other world where we do not marry.

18. See John Cornwell, Hitler’s Pope: The Secret History of Pius XII (New York: Viking, 1999), esp. chapter 7, “The Jews of Rome,” 298–318. I am not here suggesting that Cornwell’s speculations regarding the actions Hitler would have taken are correct. In fact, I doubt that they are. The point, though, is simply that the Molinist view does not require that the counterfactual stating Hitler would have stopped the deportation if Pius had intervened be false, if Pius XII does not intervene.

19. See Adams, “An Anti-Molinist Argument.” I have renumbered the propositions here, and in the critiques/responses.

20. William Lane Craig, “Robert Adams’s New Anti-Molinist Argument,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 54, no. 4 (December 1994): 859.

21. He offers a definition of explanatory priority which captures this element:

(EP/C) x is explanatorily prior to my choices and actions ≡ x is true, and there is no choice or action within my power that would cause it to be the case that x is false.

I have changed the symbol used to designate this and the other definitions offered by Flint. The definition itself remains unchanged. Flint, Divine Providence, 164.

22. Flint’s definition of explanatory priority in terms of counterfactual power:

(EP/CF) x is explanatorily prior to my choices and actions ≡ x is true, and there is no choice or action within my power such that, were I so to choose or so act, x would be false.

Ibid.

23. The proposals are in terms of logical priority, entailment, and contra-causality. They are defined respectively:

(EP/LP) x is explanatorily prior to my choices and actions ≡ x is true and there is no choice or action z within my power such that my doing z would entail that x is false;

(EP/E) x is explanatorily prior to my choices and actions ≡ x is true and, for any choice or action z within my power, my doing z would entail x;

(EP/CC) x is explanatorily prior to my choices and actions ≡ x is true and I don’t have the power to bring it about that x is false.

(EP/LP) fails because it is not transitive, (EP/E) fails because it conflicts with both (1) and (9), and (EP/CC) fails because it is too vague.

See Flint, Divine Providence, 169–71.

24. For a more recent attempt to give a definition of explanatory priority, see William Hasker, “Explanatory Priority: Transitive and Unequivocal, A Reply to William Craig,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 57, no. 2 (June 1997): 389–93. Hasker proposes the simple definition:

(EP/T) p is explanatorily prior to q iff p must be included in a complete explanation of why q obtains.

Hasker correctly points out that (EP/T) is transitive, and uses it to critique Craig’s contention noted earlier that explanatory priority functions in a different way in (1) from how it functions in (2) and (3) by an appeal to (1a), (2a), and (3a). Hasker admits that (1a) is false, given (EP/T), but (1) is indeed true because “in deciding to create those persons God did in fact consider all the counterfactuals of freedom that are actually true of them; all of these counterfactuals played a role in the process by which God came to that decision.” Ibid., 391.

Craig has responded, claiming that Hasker’s definition is “so generic that we should have to deny its transivity or so weak that it would not be inimical to human freedom.” William Lane Craig, “On Hasker’s Defense of Anti-Molinism,” Faith and Philosophy 15, no. 2 (April 1998): 239. In order to illustrate this, Craig appeals to a rather common event in which each of two persons, Mary and John, attends a party because the other is going. According to Craig, if (EP/T) is transitive, then John attends the party because John attends the party. This statement does not have any meaning and is therefore vacuous. Ibid., 238. Hasker believes that Craig’s example is faulty because he doubts that such a decision can be reflexive. Instead, he proposes that, although subtle, the decision of either Mary or John was made in successive stages as the two of them discovered that they both wanted to attend: “Mary’s initial signal is followed by John’s response, which leads in turn to a response from Mary, and so on. . . . The process may be subtle and complex, but from a causal standpoint it is perfectly straightforward, and there is no violation of asymmetry, as there is in Craig’s description.” William Hasker, “Anti-Molinism Undefeated!,” Faith and Philosophy 17, no. 1 (January 2000): 128. It seems to me that Hasker is correct on this score. Flint is also unconvinced by Hasker’s definition because he believes that it relies upon the concept of bring about which Flint has shown to be problematic. Even if a clear understanding of (EP/T) could be given which is transitive and works for (1), (2) and (3), Flint contends that it would render (8) unacceptable to the Molinist. Flint, Divine Providence, 171 n. 12.

25. It is interesting to note that Adams originally claimed that he was merely employing the concept of priority utilized in formulations of the doctrine of middle knowledge, although he did not attempt to set forth a formal definition of explanatory priority. He writes, “The central idea in this argument is that of explanatory priority, or an order of explanation. I think it is roughly the same as the idea that Scholastic philosophers expressed by the term, ‘prius ratione’ (prior in reason), but I do not mean to be committed here to any predecessor’s version of it. Even if there was no time before God decided to create us, or if God is timeless, God’s knowing various things can be explanatorily prior to God’s deciding to create us. And it is clear that according to Molinism (as claimed in premise (1)), God’s knowledge (and hence the truth) of all the true counterfactuals of freedom about us is prior in the order of explanation to God’s deciding to create us, since (by the perfection of God’s providence) they were all taken into account in that decision.” Adams, “An Anti-Molinist Argument,” 347. Flint has attempted to set forth a formal definition of priority as it is used in the Molinist schema:

(EP/M) x is prior to z ≡ In either sense (B) [(EP/CP)] or sense (B*) [x is prior to my choices and actions ≡ x is true, and necessarily, there is no choice or action within my power such that, were I so to choose or so to act, x would be false.], x is prior to God’s choices and actions, and z is not prior to them.

Flint correctly notes that (EP/M) allows the Molinist to claim that middle knowledge is prior to free knowledge and that natural knowledge is prior to both middle knowledge and free knowledge, claims that are central tenets of Molinism. However, there still seems to be an irresolvable difficulty: (EP/M) is rather vague, and (B) [(EP/CP)] alone can only make the distinction between prevolitional and postvolitional knowledge; it cannot explain how natural knowledge is prior to middle knowledge. See Flint, Divine Providence, 174–76.