Mike Milken believes in 100 percent market share.

— JOHN KISSICK, DREXEL BURNHAM LAMBERT CHIEF OF WEST COAST CORPORATE FINANCE

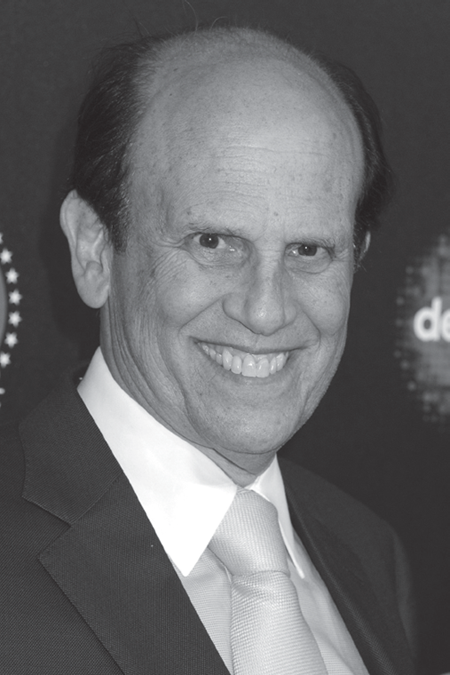

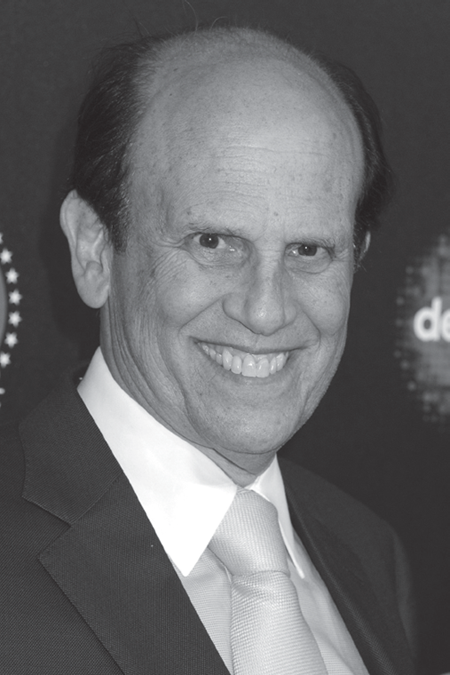

© Byron Purvis/AdMedia/AdMedia/Corbis

In the spring of 1970, I graduated from Wharton, the business school at the University of Pennsylvania. At a dean’s reception for soon-to-be MBAs a few months earlier, I had bumped into a particularly driven and single-minded classmate—when I asked him about his plans after school, he answered without hesitation that he would first become independently wealthy by working a few years at the Drexel Harriman Ripley investment banking firm and then would return to a university to teach. I might have been skeptical of this goal had it been voiced by another peer, but this was Michael Milken; already well known among faculty and students alike, it was clear he had an unusual talent for finance and business. Renowned among our cohort, he would soon be famous—and then infamous—throughout the entire financial world.

But in 1970, Milken was still just a prospective MBA graduate—albeit one with an unheard of three majors (information systems, operations research, and finance) who landed his job after one of Wharton’s finance professors told Drexel’s managing director that Milken was “the most astounding young man I have ever taught.”1 Milken achieved straight As during his MBA studies, getting grades so high that they skewed professors’ grading curves and led some A-seeking students to avoid classes in which he was enrolled. (Milken finished all of his course work and left Wharton in 1970 but didn’t receive his degree until 1973, when he finally completed the required thesis.)

My impression of Milken was as an intensely serious young man with few social or intellectual interests beyond business—but in those areas, his interest seemed boundless. Inspired not by assigned classwork but by his own desire to better understand the business world, he compiled binders full of articles and reports arranged by industry groups to more thoroughly analyze companies within the markets they served. He even asked to read classmates’ term papers if the subject piqued his enormous curiosity. I shared one of my papers with him, on how investment bankers raise money for their clients through privately placed securities offerings. He returned it with insightful comments in the margins. Who could have guessed that fifteen years later (with certainly no credit due to my elementary term paper) Milken would became famous on Wall Street for raising $1.1 billion for MCI Communications through the largest private placement of securities in history.

The topic that most consumed his interest, however, was low-rated corporate bonds. In his soft, monotonic voice, Milken could talk for hours about the investment merits of what would later be called junk bonds. While an undergraduate at the University of California, Berkeley (where he graduated Phi Beta Kappa), he had come across a little known book by W. Braddock Hickman titled Corporate Bond Quality and Investor Experience. This text set the foundation for Milken’s later career and fortune.2 Hickman’s book was not exactly a how-to manual on making money in the bond market, but it provided much of the impetus and statistical raw material on lower-quality bonds that would drive Milken’s research at Wharton. And that research convinced the twenty-three-year-old Milken that he could quickly become a millionaire by trading in a selective portfolio of bonds that were outside the investment-worthy ranges established by the Standard & Poor’s and Moody’s credit-rating agencies. At Drexel, he set out to do just that.

Making a Market

Drexel Harriman Ripley had a storied past, but—when Milken joined in 1970—an uncertain future. A century earlier, in 1871, prominent Philadelphia banker Anthony J. Drexel joined forces with the young J. Pierpont Morgan to form Drexel, Morgan & Company. The firm grew into a powerful American banking house, financing many of the era’s leading railroads and engineering a bailout of the U.S. government during the panic of 1893. Not long after, the firm split into a dual-partnership arrangement, with shared directors but separate names: New York–based J. P. Morgan & Company and Philadelphia-based Drexel & Company. The Drexel firm’s business was mainly in commercial banking, and shortly after the passage of the Glass-Steagall Act in 1933 its partners elected to merge into the J. P. Morgan operation. But in 1940, following the lead of former J. P. Morgan partners who established Morgan Stanley & Company as an investment banking offshoot of the House of Morgan, several Philadelphia partners bought the Drexel name and launched their own wholesaler investment firm. For the next few decades, they enjoyed success by trading on the long-honored Drexel reputation for investment banking excellence and conducted a gentlemanly and upscale underwriting business for companies with whom they had preserved longtime personal and business connections.

By the time Milken arrived in 1970, Drexel had combined with another old-line investment house, Harriman Ripley & Company. And though the resulting Drexel Harriman Ripley had a rich combined history of financing railroads and early twentieth-century industrial companies, their roster of blue-chip corporate clients was shrinking below the level necessary to conduct a viable investment banking business. The only reliable client the firm could count on for ongoing stock and bond offerings was the Philadelphia Electric Company.

Over the next twenty years, Milken would transform Drexel into a high-flying investment banking firm far beyond the imagination of the current or prior Drexel partners. But when he first joined he was assigned to less glamorous projects, many of them in the firm’s “back office.” One of the back office projects involved revamping the way Drexel delivered its securities, with Milken’s recommended improvements purportedly saving the firm about a half-million dollars per year.3 The back office assignments were productive, but Milken wanted to pursue work in the firm’s research and trading departments, where he could apply his academic studies on low-grade bonds to the real world. The firm acceded to his wishes, but there was one catch: he would have to transfer from Philadelphia to the New York office.

The prospect of living in New York held little appeal for Milken. His wife Lori was enrolled in graduate school and working as a research assistant on a history of the University of Pennsylvania. Uprooting themselves from their Philadelphia home for what could be a short-lived assignment seemed unwise. What’s more, they both missed California and their families and planned a return to the West Coast as soon as an opportunity arose.

The solution Milken settled on was commuting by bus to and from New York, leaving before sunrise and not returning until midevening. But he made those long commutes—two hours each way—highly productive. He boarded the bus with tote bags full of research reports and securities filings on the issuers of low-grade bonds, and spent the trips in nondistracted study. He eschewed the faster and more comfortable commuter train, preferring the bus’s assured anonymity and the near certainty of an adjacent empty seat for his bags of paperwork. (His routine was well known to colleagues, and one gave Milken a gag gift of a miner’s hat with an attached light to better illuminate reading material during the dark hours of his bus trips.)

The prodigious amount of research he dedicated to his bond endeavors, both on the bus and off, is important in explaining his ultimate success. Making money on low-rated bonds was not just a matter of reading Hickman’s book on the historic yields available on such bonds and then dedicating money to that market segment. By their nature, bonds with a weak credit standing, namely those carrying BB, B, CCC, and lower ratings, have greater inherent risks, and their purchase demands more scrutiny and a thorough knowledge of the underlying business. Bond salesmen and traders had an easier time of it when dealing in bonds rated AAA, AA, A, and BBB, relying on the credit agencies’ assessment of investment quality and the risk of default. A pleasant personality and a decent golf swing was often enough to forge a lucrative career in selling low-risk bonds.

Milken, meanwhile, did not play golf and could hardly be described as congenial. He would ultimately wear the (not-so-cherished) mantle of “Junk Bond King,” but the first leg of his road to success required convincing the innately conservative bond buyers of the day on the merits of junk bonds—or, as he preferred to call them, high-yield bonds. It was a hard sell. When he began on Drexel’s bond research desk in the 1970s, the supply of junk bonds was composed entirely of “fallen angels”: bonds that had once been investment grade but were subsequently downgraded to “below investment grade” status. A bond analyst or trader at an insurance company or an investment advisor in a staid trust department of a bank could hardly be faulted for a lack of interest in such maligned bonds. And it did not help Milken’s cause that he was just in his midtwenties when he set out to change the world of bond investing. Or that he covered his premature baldness with an ill-fitting toupee and wore clothes that looked to be straight off the rack. Or, for a sizable percentage of institutional investors who occupied the buy-side desks on Wall Street, that he was Jewish.

But if he could get an audience, Milken was often able to make a compelling case for one or more of his fallen angels. If the prospective bond buyer had been trained through a strict Graham and Dodd approach to securities analysis—one, that is, that relied on demonstrating that the issuing company had ample cash flow to make principal and interest payments and had sufficiently valuable assets to back up the bonds—Milken was at the ready. Many of the junk bonds of the day had been issued by conglomerates formed in the 1960s that were struggling with their unwieldy collections of diverse businesses. Once-prominent companies such as AVCO, Ling-Temco-Vought, Rapid-American, General Host, and City Investing had suffered downgrades from credit agencies as their fortunes waned. But through endless hours poring over complex financial statements and industry statistics, Milken (like Benjamin Graham before him) was able to ferret out investment value and safety that had escaped the notice of less conscientious analysts. He could answer every question about the bond issuer’s business prospects and balance sheet, and more importantly, he could paint a convincing picture as to why many of the fallen angels, with their high yields, could provide a very enticing return on investment—and could do so with a much lower level of risk than their bond ratings suggested.

If the bond buyer was attuned to the academically based “modern portfolio theory” coming out of the business schools, so much the better. This approach called for investment managers to control risk by balancing their portfolios with a mix of two very different securities: investment-grade bonds and common stocks. If the manager wanted to lower the portfolio’s risk, he would weight the investment mix toward the bonds; if he was feeling less risk averse and was more interested in higher returns, he would move toward a higher proportion of stocks. But now Milken was advocating a third component: non-investment-grade bonds that were more risky than their investment-grade counterparts but less so than common stocks. With Hickman’s study of the corporate bond markets between 1900 and 1943, and the update by T. R. Atkinson for the years 1944 through 1965, Milken had the statistics to back up his pitch.4 Some small percentage of the lower-rated bonds went into default, leaving their holders with a substantial loss of principal value, but on average the return realized on those bonds more than made up for a few losses. Over time, Milken argued, a portfolio of riskier but higher-yielding bonds was much more profitable than a portfolio of investment-grade bonds. And history showed that, when compared with common stocks, the returns to high-yield bondholders were smaller, but the risks were lower, because with any bond there was a contractual obligation from the issuer to make the payment of the bond’s principal amount upon maturity. As Milken explained it:

No matter how much research you have done regarding a particular stock, you don’t have a contract as to what the future price will be. But with a high-yield bond there is a date certain in the future when it matures, and if you hold it to maturity and your analysis is correct, you will be correct in your calculation of your yield—and you do have a contract as to future price. One is certain if you’re right. The other is not.5

While the investment logic for junk bonds may have been compelling, their lack of liquidity in the marketplace often remained a final stumbling block for the potential buyer. With few buyers and sellers in the high-yield bond market, investors faced an unwelcome prospect of holding a bond to its maturity date as the only sure way to be paid. Milken solved that liquidity issue by assuring those investors that Drexel would always be ready to buy or sell the bonds it was promoting. He was able to make this promise because, in addition to his encyclopedic knowledge of the bond issuer’s business and financial position, he knew one other crucial set of facts: which financial institutions owned the bonds and what their inclination might be for buying or selling them. With this information, and a capital allocation of $500,000 from Drexel, Milken developed the first secondary trading market for junk bonds on Wall Street.

A 35 Percent Arrangement

On its face, a junk bond trading operation lodged within a white-shoe firm like Drexel Harriman Ripley was a puzzle. With its elitist, wholesaler pretensions, the firm had limited most of its trading in bonds to the shrinking list of investment grade–rated corporations it could still count as clients. Bond trading was merely an accommodation to its investment banking clientele, not a profit generator. As Milken began his junk bond operation, one of the high-grade bond traders confronted a Drexel top executive with a demand that Milken be fired lest he tarnish the firm’s reputation among the Fortune 500 firms it was pursuing. The executive responded by asking, “Milken on a modest capital base is making money, while your high-grade department on a large capital base is losing it. Now, whom should I fire?”6 Milken stayed, and the advocate for his firing was soon gone. It was an early indication of Milken’s growing influence at Drexel.

In 1971, Milken’s nascent power base expanded further when the ailing and capital-poor Drexel was acquired by the much stronger Burnham & Company, to become Drexel Burnham & Company. While the name Burnham Drexel & Company (or even just Burnham & Company) would have been more in keeping with the reality of the arrangement, pedigrees were important in the investment banking hierarchy of Wall Street at the time, and Drexel’s name retained a cachet that Burnham’s, associated with the second tier of investment bankers, lacked. Before the merger took place, Burnham’s founder and majority partner, I. W. Burnham II—nicknamed “Tubby” throughout his life following a brief period of plumpness as a child—consulted with other firms on the new name. Morgan Stanley (then the arbiter of such things in the caste-like rankings of underwriters) advised Burnham that the combined firm should be called Drexel Burnham if it wanted to participate in Wall Street’s securities offerings as one of the top bracketed firms.

The new Drexel Burnham would prove to be a more hospitable home for Milken for reasons far removed from underwriting brackets. Burnham & Company’s principals were predominantly Jewish, and when Tubby Burnham was doing his due diligence prior to the acquisition, he inquired about the number of Jews who were part of the Drexel organization. Drexel’s president at the time, Archibald Albright, said that just a few of their two hundred fifty employees were Jewish. He elaborated: “They’re all bright, and one of them is brilliant. But I think he’s fed up with Drexel, and may go back to Wharton to teach. If you want to keep him, talk to him.”7

Burnham did talk to Milken, and discovered that the source of his unhappiness was that Drexel was allocating only $500,000 of the firm’s capital for junk bond trading—even though he was earning a 100 percent return per year on that capital. He also discovered, after Milken provided him with a lengthy tutorial on junk bonds, that “brilliant” was an apt description, and committed on the spot to increase his capital allocation to $2 million. Much more crucial for its long-term ramifications, however, was the deal that Burnham cut with Milken providing that employees of the high-yield trading operation would receive 35 percent of the profit they generated, to be divided among the traders however Milken saw fit. That incentive no doubt helps explain why the Drexel high-yield group lost money in only three months during their seventeen-year run—and also explains how Milken, who shared in those profits, eventually became a billionaire.

With a larger capital base, “the Department” (as Milken’s junk bond operation came to be known within Drexel) expanded with respect to both the number of traders and its book of clients. Milken’s approach to attracting those institutional clients was short on charm but long on substance. He had never developed any sense of style, and with his shabby suits he could still be confused with a clerk from the firm’s back office. But with an inexhaustible knowledge about junk bonds, he could speak at whatever level of detail the prospective institutional investor required. And by the time he met with investors, he had done enough investigation into each institution’s investment portfolio to tailor a junk bond pitch precisely to its apparent needs, be it an insurance company, pension fund, bank, or mutual fund.

It wasn’t long before Milken evolved from the role of salesman, explaining the merits of high-yield bonds, to the much broader and more influential role of trusted investment advisor. In 1973, his guidance was behind the conversion of the First Investors Fund for Income from an investment-grade bond mutual fund to a high-yield bond fund—and as a result, First Investors was the country’s best-performing bond fund in both 1975 and 1976.8 And while mutual funds represented a fertile new market to which he could spread the junk bond gospel, the insurance industry held even more appeal. Insurance companies were major purchasers of corporate bonds, and Milken enticed several of them, including old-line carriers such as Massachusetts Mutual, to diversify from investment-grade bond portfolios by giving them a sampling of his offerings from the junk bond arena. Much of his new business, however, came from institutions that had recently come under the control of mavericks who acquired insurance-based financial conglomerates through hostile takeovers—familiar names from the 1970s, they included Laurence Tisch (CNA Financial), Carl Lindner Jr. (American Financial Group), and Saul Steinberg (Reliance Insurance Group). For each of these companies, Milken designed as well as implemented much of their high-yield investment strategies.

One bedazzled institutional investor, after a visit to Drexel’s bond operation, summed up Milken’s accomplishments by stating: “He had the issuers. He had the buyers. He had the most trading capital of any firm. He had the knowhow. He had the best incentive system for his people. He had the history of data—he knew the companies, he knew their trading prices, probably their daily trading prices going back at least to 1971. He had boxed the compass.”9

Yet Milken had a major and fundamental problem in the early 1970s: he was faced with a limited supply of product. His promotion of high-yield investing had led to many recent converts and fresh entrants to his markets, thereby fostering a growing demand for junk bonds. But the problem was on the supply side. New fallen angels continued to drop into his orbit, but the number of junk bonds was also being depleted as issuers were acquired by larger, more creditworthy companies. Compounding the shortage were rising stars, the once junk-rated companies that moved back into the investment-grade sphere. And, of course, some of the fallen angels fell even further, disappearing into bankruptcy. With the rise and fall of new and old fallen angels, Milken had only about twenty-five separate junk bond names to trade. That stasis, however, ended shortly after the 1974 arrival of Frederick Joseph at Drexel Burnham.

“Let’s Do Some Deals”

The combination of the blue-blooded investment bankers of the old Drexel with the hard-driving traders and salespeople from the Burnham side was bound to create problems, and it did so without much delay—especially on the investment banking side. The conflicting missions of the old and new versions of Drexel investment banking were colorfully described by a former Drexel & Company banker who said, “The Drexel people were sitting at one end of the hall, waiting for Ford Motor Company to realize it had made a mistake and call us up and tell us that they’d really appreciate it if we would take them back. And you had the guys from Burnham and Company running around Seventh Avenue trying to underwrite every schmate factory they could find.”10

Recognizing the incompatibility of the two approaches, the combined Drexel Burnham fell back on the often-used but rarely successful solution of naming coheads to direct its investment banking operation. But in reality, there was little business to direct. Drexel’s stable of clients included a few remaining Fortune 500 companies, mixed in with many decidedly smaller and lower-quality companies. So when Fred Joseph was recruited to represent the “Burnham side” to complement John Friday on the “Drexel side,” the investment banking business was essentially a turnaround project.

The son of a Boston cabdriver, Joseph had gone on to become a collegiate boxing champion at Harvard College and later earned an MBA from Harvard’s graduate business school. From there, he had gone on to work for two of the larger Wall Street firms of the time, E. F. Hutton and Shearson Hammill. Joseph had a history of setting and achieving lofty goals and had been on the lookout for a place to build a major investment banking operation from the ground up. When he interviewed for the codirector position at Drexel in 1974, he stated confidently that he would build a business that in ten to fifteen years would rival the likes of Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley. It was the kind of naked ambition that many on Wall Street were imbued with—but no one else would enjoy the good fortune of having Michael Milken as a business partner.

Joseph’s plan for building an investment banking powerhouse was based on a strategy of raising capital for up-and-coming businesses that were too small or too risky for the major firms—or for the once-exclusive Drexel Harriman Ripley. The timing for such a strategy could not have been better. During the troubled 1970s, medium-sized businesses, regardless of their potential for growth and development, had few places to go for expansion funds. The stock market was inhospitable for fast-growing companies looking to go public. Only a handful of such companies—“special situations” of one kind or another—could attract a willing underwriter. In normal years, hundreds of companies launched initial public offerings, but in 1974 there were only nine IPOs, and in 1975 the number dropped to six. And there seemed to be no way to float a bond offering for a company that was not sporting an investment-grade rating. To make matters worse, the ranks of the smaller, “sub-major” investment firms, whose corporate finance departments once catered to small- to medium-sized businesses, had greatly thinned during Wall Street’s problem years of the mid-1970s. In most cases, the only financing alternative for a medium-sized company was a commercial bank or sometimes a receptive insurance company. In short, when Joseph arrived at Drexel Burnham, there was a large pent-up demand for capital but a dwindling supply of it.

Milken was running his lucrative bond trading operation at a far remove from the rest of Drexel Burnham investment bankers, but when Joseph got around to meeting Milken he realized that he had not only come across an uncommonly bright trader who had a desire for success and market share that rivaled his own, he’d also found an answer to his capital shortage. Joseph knew of an untold number of low credit–grade companies that were being shut out of the capital markets, while Milken’s operation was strapped by a shortage of junk bonds available in the market. They quickly realized they could solve each other’s problems, and their first meeting ended with Joseph saying, “Let’s do some deals together.”11

And deals they did. Over the next several years Drexel Burnham Lambert—a transaction with Belgian-based Groupe Bruxelles Lambert resulted in a major capital infusion into the newly named Drexel Burnham Lambert—prospered by developing a new form of financing: bonds that began their lives in the capital market with below–investment grade ratings and high interest rates. In one of the most important developments of modern investment banking, Joseph and his team found a way to raise capital for clients by floating newly created junk bonds.

Drexel would eventually dominate the market for new-issue junk bonds, but the first such bonds were offered in 1977 by Lehman Brothers—then one of Wall Street’s elite investment bankers—for low-rated but familiar companies such as LTV Corporation, Zapata Corporation, and Pan American World Airways. Later in that year, Drexel made its junk bond debut by underwriting an original issue of $30 million of bonds for Texas International, an oil and gas company. The firm sponsored six other junk bond offerings in 1977 and raised a total of $125 million but still lagged behind Lehman in the new junk bond category. In 1978, however, Drexel’s volume of junk bond financing soared to fourteen offerings totaling $439 million, leaving Lehman Brothers and all other investment banking firms far behind. In short order, Milken and Joseph had put a rejuvenated Drexel Burnham Lambert back among the major investment banking firms.

Westward Expansion

By the late 1970s, Drexel was thriving. At the beginning of that decade it had been on the ropes, with no apparent direction and few profitable operations, but by the end, with its new focus on junk bonds, it reemerged in good financial health. The investment bankers were able to command underwriting fees on new junk bond issues of between 3 to 4 percent of the gross amount being offered—by contrast, underwriters of investment-grade bonds charged less than 1 percent for the same services—and Milken continued to oversee a profitable and rapidly growing trading operation. With a junk bond–based mission, Drexel abandoned the low profits of the high-quality segment of the bond business, and John Friday, once Joseph’s codirector of investment banking, was pushed out.

And as Drexel prospered, so did Milken. Because of his growing position of power within the firm, he was successful in extending the Department’s 35 percent share of trading profits to include profits realized from investment banking work that involved junk bonds. Milken retained sole discretion on how the Department’s bonuses were distributed, and as would be the practice during Milken’s reign as Junk Bond King, he allocated much of the 35 percent to himself. Still, many of the traders, salespeople, and research analysts who worked for him began making incomes well into the six figures.

Compensation at that level is not that unusual nowadays for Wall Street bankers, but in the 1970s it was considered a staggering amount and, of course, bought a great deal of loyalty to Milken. So in 1976, when he first broached the idea of moving the high-yield department from New York City to Southern California, there was little resistance from those who worked for him. All of the important players in the Department went along with the move, with only a few clerical workers opting to stay behind in New York.

More surprising was the lack of resistance from the top management of Drexel. Tubby Burnham and Fred Joseph knew that Milken and his operation would be hard to control three thousand miles away, but they understood the reality of the situation: no matter how they crunched the numbers, the Department was responsible for the firm’s new levels of profitability. If Milken wanted to return home to the Southern California lifestyle he and his family had missed for the last ten years, they’d let him do it—as long as he continued to ship back 65 percent of the profits back to New York.

With little fanfare and with not so much as a sign on the door, the West Coast operation of Drexel Burnham Lambert opened in Century City on July 3, 1978, one day before Milken turned thirty-two. It was home to the same cast of characters who had worked together successfully in New York, but with one major modification: the workday began at 4:30 in the morning to accommodate the three-hour time difference between New York and California. Milken sold his transplanted work crew on the notion that the change would result in an enhanced family life, since the trading day would end three hours earlier. In reality, at least for Milken, it just extended the number of working hours in the day. He arrived home in Encino—not far from where he and Lori grew up—about the same time the bus rolled into Philadelphia when he worked on Wall Street. Now he just left home even earlier in the morning.

The business from the new California base exploded. By 1983, Drexel’s junk bond financing increased more than tenfold to $4.63 billion. All told, Drexel underwrote 276 new issues of junk bonds in that five-year span, with proceeds to the corporate issuers totaling $14.6 billion, including the $1.1 billion offering for MCI Communications, the up-and-coming challenger to AT&T for the long-distance telephone business.12 And Milken—with a vast web of institutional investors who trusted his investment judgment and secondary trading prowess—was arguably the only investment banker with the credibility to engineer billion-dollar deals.

Most of the money he raised went to companies that had no alternative means of tapping into the capital markets, or at least not to the extent they could under Drexel’s sponsorship. Milken and his acolytes often ascribed more lofty aims than mere moneymaking to their activities, and it is certainly true that not just new companies but the growth and development of whole new industries, including much of the cable television, telecommunications, broadcasting, and gaming industries, were powered with junk bonds. Just as the level of venture capital financing grew exponentially after its locus shifted from Boston to California’s Silicon Valley in the 1980s, the junk bond business took off after the move to Los Angeles. Comparisons between the two types of financings and their positive effects on the economy quickly grow strained—the case for venture capital is much easier to make—but it’s true that much of the new capital raised by the less tradition-bound West Coast financiers was initially put to productive use and spurred significant economic growth.

Whatever the salutary effects of junk bonds on society and the economy through 1983, the effects on Drexel and Milken were unequivocally positive. Drexel, the once-prominent investment banking firm of J. P. Morgan and Anthony Drexel, was making a resurgence, and in the closely watched “league tables”—the periodic listing of where investment bankers place by activity—the firm had risen to the number six spot for underwriting corporate securities. It was once again, as Joseph had brashly predicted just ten years earlier, operating in the top tier of investment banking firms. Milken shared handsomely in that success; his 1983 tax returns showed personal income of $47.5 million.13

His fortune was made, but Milken showed no interest in following up on his earlier plan to move to academia. Instead, he ratcheted up his business further by seeking other uses for junk bonds. He was especially intrigued by the idea of extending their use to international finance, in particular by providing a means to fund the development of emerging-market countries. Unfortunately, his fertile mind was diverted from the more idealistic field of development finance to the more immediate and lucrative opportunities in the roaring mergers and acquisitions markets of the 1980s. It would prove to be a disastrous decision for both Milken and Drexel.

Highly Confident

Drexel’s West Coast business soon relocated from Century City to Beverly Hills, and it was there, in November 1983, that Milken, Joseph, and a select group of Drexel’s corporate finance officers conceived of a new application for junk bonds. The strategy they plotted, which they believed would provide a “quantum leap” in the level of their business, was to make junk bonds an integral part of a corporate transaction called a leveraged buyout. It was the dawn of the so-called LBO, a form of acquisition that was spurred by the remarkably quick and successful buyout of Gibson Greeting Cards in 1982 by an equity group put together by former Treasury secretary William Simon. An LBO involves purchasing a company largely through the use of debt (hence, the transaction is “leveraged”), so the buyer can use just a token amount of its own equity capital and a much larger amount of “other people’s money” procured through borrowing. About 60 percent of the acquisition funding typically came from commercial banks that secured their loans by using the target company’s assets as collateral, and another 10 percent or so was supplied by the new owners of the company in the form of common stock equity. The toughest money to locate, however, was “mezzanine” debt—the unsecured financing level between the collateralized bank debt and the new owners’ equity. If it could be found at all, such debt was usually available from a small number of aggressive insurance company lenders or specialty mezzanine finance funds and only after prolonged business investigations and the negotiation of a long list of restrictive conditions.

Milken and Joseph realized that junk bonds, with their long-term maturities and light terms and conditions, provided a much faster and more appealing way to apply leverage. The only problem was that Drexel was just a middleman and did not, like an insurance company or a mezzanine fund, have the figurative vault from which to draw the funds. For good reason, a prudent board of directors was chary of approving an LBO without all of the financing firmly in place, including the linchpin mezzanine money. By 1983, however, Drexel had developed such a formidable reputation that Joseph and Milken believed a “highly confident letter” could be issued to assure all parties to the deal that the firm could bring the necessary funds to the closing table. This idea raised skepticism among Drexel’s mergers and acquisitions competitors on Wall Street and the whole idea was derisively referred to as Milken’s Air Fund.

But just a few months later, Milken proved that he could deliver. T. Boone Pickens, one of the country’s most effective and feared takeover operators, had hired Drexel to raise a staggering $1.7 billion in advance of his attempted hostile takeover of Gulf Oil by his much smaller acquisition vehicle, Mesa Petroleum. After the proposed deal was publicly announced, Milken quickly came through with commitments for the $1.7 billion—promising more if needed. Gulf was ultimately acquired by Chevron Corporation, which acted as a “white knight” to counter the acquisition by Mesa, but Pickens still made a great deal of money, having already purchased many shares of Gulf stock at prices far below the $80 per share price that Chevron wound up paying. And with Milken’s remarkably fast procurement of almost $2 billion, Drexel’s highly confident letter was no longer referred to as the Air Fund.

It was after this transaction that Milken lost the anonymity he had always coveted. He had never sought a high profile in high finance—he was listed in Drexel’s annual reports as merely a vice president—but the Pickens transaction forced Milken into the limelight of Wall Street financiers. Financing engagements for Drexel soon followed from the leading takeover players of the day, including Carl Icahn, Sir James Goldsmith, and the LBO firm of Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Company. With its dominance in LBO financing, Drexel climbed another four spots in the league tables, occupying the number two spot among the underwriters of corporate debt securities in 1984, just behind Salomon Brothers. Through the remainder of the 1980s, Drexel, with its ability to raise vast amounts of mezzanine money, was a key player in the rise of record-sized LBOs that included the buyout of Beatrice Foods, Union Carbide, and, ingloriously, the highly controversial $25 billion buyout of RJR Nabisco in 1988. Between 1984 and 1990, LBOs consumed $216 billion in junk bond financing.14 For much of that time, Milken was at the controls.

As Milken’s notoriety grew, comparisons to J. Pierpont Morgan became commonplace; no one since Morgan had wielded such financial power, and like the venerable Morgan, Milken had a string of large financial institutions lined up to fund his transactions at a moment’s notice. Also like Morgan, he was a divisive figure that was either revered or hated by the public. But whereas Morgan was generally held in high repute by the business elites and Wall Street, Milken was loved mainly by scrappy entrepreneurs and takeover specialists and was despised by much of the business establishment—especially by organizations such as the Business Roundtable (an organization of CEOs of large corporations, many of whom feared a Milken-engineered hostile takeover) and by the prominent investment banking firms that eschewed, at least initially, the ungentlemanly business of hostile takeovers. Many dismissed Drexel Burnham Lambert as “junk people and junk bonds” and seemed eager to see the firm implode.

100 Percent Share

Drexel’s critics would not have to wait long for the implosion. Indeed, while the firm was making record profits and climbing to the top rungs of investment banking during the glory years of the 1980s, its West Coast office, the source of most of its success, was also careening dangerously out of control under Milken’s loose management.

In well-run investment banking firms, there are checks and balances and systems of quality control, but Drexel failed to put those measures in place with respect to its Beverly Hills operation, dubbed by many in the home office as the Wild West. At the New York headquarters, Joseph had formed the Underwriting Assistance Committee to, ostensibly, approve investment banking commitments. Milken paid little heed to the decisions of this feckless group, and if they disapproved of a deal that he proposed, he simply flouted the firm’s internal rules and did it anyway. Furthermore, in the Beverly Hills operation, there were no real boundary lines between departments—referred to as “Chinese walls” in the investment business—to assure that the confidential information the firm’s bankers held about a transaction was kept separate from the traders and sales force. Milken’s California organization, in reality a full-scale investment banking operation, shared information among its employees indiscriminately. Indeed, Milken was given complete freedom to run the Beverly Hills firm with no apparent input from New York management. At the height of its activity, the Beverly Hills office was transacting two hundred fifty thousand trades per month, yet they were coded in a way that only Milken understood. The carving up of profits, the levels of inventories, and the settlement of trades were all in accordance with Milken’s preferences. He set up partnerships among his cronies and members of his family through which he funneled the firm’s profits with minimal approval and oversight.

Although loose management was a major ingredient in the recipe for disaster, another ingredient, even more problematic, was Milken’s growing propensity to ally himself and Drexel with bad actors. When the LBO boom got under way in the 1980s, Milken funded some tough and controversial people (like Carl Icahn and T. Boone Pickens) who earned the enmity of establishment bankers and corporate America. They were smart and pushed the boundaries of fair dealing but seemed to be playing by the rules. But as time went on, Milken became the source of acquisition funding for more questionable corporate raiders and Wall Street operators. In his rabid pursuit of more deals, his associates in the Beverly Hills office and his nominal supervisors at the New York headquarters understood that “Mike Milken believes in 100 percent market share.” Quantity often trumped quality. And despite an awe-inspiring thoroughness when it came to the facts and figures of the billions of dollars of transactions he masterminded, he had a fatal blind spot when it came to the people behind the deals. And no one proved more fateful for Drexel and himself than Victor Posner and Ivan Boesky.

Even Joseph, whose New York corporate finance department was staffed with an unusually aggressive and rule-testing breed of investment bankers, knew that Posner was nothing but trouble. One of the shadiest takeover players of the 1980s, Posner was an unsavory Miami wheeler-dealer who was routinely under investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission and had pleaded no contest in a recent charge of tax fraud. After Joseph ordered a study into Posner’s businesses, he became alarmed with the pattern of noncompliance with securities regulations and the performance of the several companies under his control. The Drexel banker who completed the study on Posner concluded that Posner had a history of “turning gold into dross.”15 But when Joseph voiced his very reasonable objections to doing business with him, he was steamrolled by the strong-minded Milken and his “100 percent market share” ambitions; Posner was retained as a client in several takeover transactions.

Ivan Boesky was another Milken-championed client. Drexel’s New York bankers were as wary of Boesky as of Posner, and initially balked at any representation of him. Boesky had been wildly successful in the frantic mergers and takeover business of the 1980s by engaging in merger arbitrage, which involved making large bets on whether an announced merger transaction would actually close. There was always some uncertainty as to the completion of a merger, since an agreed-upon deal could go off the rails for any number of reasons (including regulatory and antitrust problems, due diligence issues, or just unfavorable market developments). Because of that uncertainty, the target company’s stock almost always sold at some discount to the anticipated value of the deal during the weeks or months prior to a final closing. “Arbitrageurs” like Boesky made large and leveraged bets on the actual completion of transactions and, if correct, benefited handsomely. The bets were informed by whatever the arbitrageur could dig up—including inside information known only to the corporate executives, investment bankers, attorneys, accountants, and others with access to such privileged information. Although acting on inside information was illegal, the SEC was less than vigilant in pursuing suspected insider abuse. Boesky used whatever means he could, including bribery, to gain profitable information on which to base his bets.16

During the early to mid-1980s, Boesky appeared prescient and established a remarkable record of success as an arbitrageur. He craved public approbation and in 1985 wrote a book about his business: Merger Mania: Arbitrage, Wall Street’s Best Kept Money-Making Secret. In the same year he gave the commencement address to the business school graduates at Berkeley (Milken’s alma mater), telling his young listeners: “Greed is all right, by the way. I want you to know that. I think greed is healthy. You can be greedy and still feel good about yourself.”17 Those lines, simplified to “Greed is good,” were immortalized by the Gordon Gekko character in the movie Wall Street.

Among the cognoscenti on Wall Street, including the bankers and traders at Drexel, there was little doubt that Boesky’s arbitrage gains were ill-gotten. So when Milken proposed a plan to raise $640 million for Boesky’s arbitrage partnership, there was strong and well-grounded resistance from the more discerning Drexel bankers. Members of the firm’s Underwriting Assistance Committee argued that the real and perceived conflicts of interest would be overwhelming, since many of Boesky’s arbitrage bets would be on the very deals that Milken and the firm’s LBO group were engineering. Since it was always Milken’s policy to take a financial interest in clients, there was a built-in temptation to steer information on the deals to Boesky for mutual benefit. And even if there was no actual illegality involved, the appearance of the arrangement looked suspect—and Drexel, with its entrance into the often controversial LBO arena, already had enough reputational problems to deal with. But as with so many other transactions that the committee disapproved, Milken simply ignored the firm’s internal procedures and raised the money for Boesky anyway.

Milken also ignored the better instincts of his brother Lowell and his wife Lori. Lowell, a prominent tax lawyer in Los Angeles, began working at Drexel when the Department moved from New York to California, handling many of Milken’s legal and administrative issues. He was both a consigliore and confidant to Milken, offering personal advice as well as business and legal advice—and one piece of advice was to be wary of Boesky. Lori’s advice, based more on Boesky’s objectionable personal behavior than on his business practices, was the same. Neither Lowell nor Lori would take or return any of Boesky’s repeated telephone calls—but Mike would usually pick up.

A $5.3 Million Payment

The events that eventually took down Drexel, and then Milken, involved both Posner and Boesky. During the early 1980s, Posner had been engaged in a protracted takeover attempt of Fischbach Corporation, a publicly traded New York-based electrical contractor. According to SEC rules, investors were required to give public notice when they had accumulated an amount of stock that exceeded some threshold and to further state their intentions regarding any attempts to wrest control of the company. Posner complied with that SEC requirement by filing a Schedule 13-D form with the SEC. That was followed by a “standstill agreement” with Fischbach under which Posner agreed not to purchase any additional stock of Fischbach, unless a rival suitor purchased enough stock to require the filing of another Schedule 13-D.

At that point, Milken began to act on behalf of Posner—again over the objections of his purported bosses in New York. Milken’s power in the acquisitions market was based on his ability to control both the issuers and buyers of his high-yield bonds and to maneuver them like chess pieces in furtherance of his goals. In 1983 he had one of his oldest and most loyal junk bond buyers, Executive Life Insurance Company, purchase enough stock in Fischbach to trigger the end to the standstill agreement—even though an insurance company was not a logical buyer of Fischbach. When that tactic backfired because of legal technicalities, Milken called on Boesky to “park” Fischbach stock in one of his arbitrage funds on Posner’s behalf. Parking is illegal under securities laws, because it violates the full-disclosure rules of the SEC regarding the actual parties to an acquisition; it also was in violation of the standstill agreement between Posner and Fischbach, since by using a straw party under Milken’s direction to acquire stock, Posner was by no means “standing still.”

To entice Boesky to take multi-million-dollar positions in Fischbach, Milken assured him that upon the ultimate takeover, whether by Posner or another purchaser, there would be a substantial increase in the stock price—and if not, Milken promised to make Boesky whole through profits on other unrelated transactions between him and Drexel. Boesky agreed to the no-lose proposition and by 1984 had accumulated enough stock to trigger the filing of his own 13-D—with no disclosure in the filing of any understandings with Milken—and also to trigger the end of the standstill agreement that blocked Posner’s takeover attempt.

Then, in 1985, Milken assisted Posner in securing enough money to purchase the Fischbach stock from Boesky by selling securities in one of Posner’s affiliated companies, Pennsylvania Engineering. Posner used the proceeds of the offering to buy sufficient Fischbach stock to be in full control of the company. He became its chairman in October. Posner got his prey and Drexel earned tens of millions in underwriting and advisory fees in connection with the Fischbach transaction. But Boesky, based on the prices at which he bought and sold the company’s shares in his parking role, wound up losing money.

Despite repeated calls to Milken and his lieutenants in Beverly Hills during and after the Fischbach takeover, Boesky received no guarantee that he would receive his promised compensation. Yet Boesky knew exactly how much he was “owed” by Milken from the Fischbach arrangement. In frustration, he wrote a cryptic note to Milken, with a demand to resolve the matter, referring to his vaguely titled “Special Projects” file—and Milken promptly satisfied his tacit agreement with Boesky by arranging a number of profitable trades involving high-yield bonds under his control.

The Fischbach transactions, however, were not the only ones detailed in Boesky’s Special Projects file. Over the years, as later alleged by the SEC and U.S. prosecutors, he and Milken kept a running account of the profits and losses involved from parking and other related transactions. Sometimes Milken would park securities to disguise the true ownership of Boesky; at other times, one instance being the Fischbach transactions, Boesky would park for Milken and his clients. So at any time, who owed whom could shift between Milken and Boesky. In 1986, the balance was in favor of Milken—nominally Drexel—and Boesky owed $5.3 million. In March Boesky made payment to Drexel to settle the account in that amount.

The problem with that payment arose when Boesky’s arbitrage funds were being audited, at which time he brushed off the auditors’ request to explain the purpose of the payment to Drexel, calling it just a “consulting fee” he owed the firm. In response to the auditors’ dogged insistence on more backup documentation, he coaxed the Beverly Hills officials into providing an after-the-fact letter for substantiation. The resulting letter, signed by Lowell Milken, stated that the $5.3 million was paid for “advisory and consulting services.”18 If any piece of evidence could be called a smoking gun in the legal investigations into the business of Drexel and Milken that followed, it was that letter.

Path to Conviction

As with so many other high-flying financiers, Milken’s great success had a hand in his downfall. By 1986, the year that would mark the beginning of his problems, more than nine hundred companies had issued junk bonds—more than the number of corporations raising capital with investment-grade bonds. Each month, billions of dollars of new money flowed into companies that only a few years earlier had no access to the long-term capital markets to fund their growth. Milken could rightfully claim that his junk bond innovation was contributing to the real growth of the U.S. economy. Less convincingly he could point to the power his junk-financed LBOs had in shaking out complacent and low-performing managements and making American industry leaner and tougher and better able to compete in world markets. He believed in the efficacy of junk bonds to his very core.

But the benefits of operating lean and mean were by no means universally shared. Corporate management and union officials were aligned in their perception of the evils that junk bonds and hostile takeovers presented. Opponents of takeovers cited the inevitable reduction in the number of employees following a takeover and the dangers takeovers posed for the continued stability of long-established corporations. And they pressed their concerns to their legislators.

Before long, states were adopting antitakeover protections for their local corporations; state insurance commissions began lowering the amount of permissible junk bond purchases; and, at the national level, Congress opened hearings on takeovers and junk bonds. Congressman John Dingell convened a hearing on the issues, and his opening statement left little to the imagination regarding the direction in which his committee was heading: “Companies which have existed for decades, which have carried the brunt of our national defense through two World Wars, which have provided employment in the heartland of America, no longer exist. They have been victims of takeovers, financed through the junk bond market.”19

William Proxmire, chairman of the U.S. Senate Banking Committee, also took up the issue. He convened hearings in 1986 to investigate the practice of takeovers, asking at the beginning of the deliberations: “How much do we really know about the corporate takeover game and the complex network of information that circulates among investment bankers, takeover lawyers, corporate raiders, arbitrageurs, stock brokers, junk bond investors, and public relations specialists?”20 Evoking the spirit of the Pecora hearings of more than fifty years earlier, Proxmire emboldened Rudolph Giuliani, since 1983 the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, to be “the Ferdinand Pecora of the 1980s” by looking for instances of insider trading, and bringing the culprits to justice.21

Giuliani readily took up Proxmire’s open-ended charge. He had made a name for himself in his first few years on the job with high-profile prosecutions of organized crime figures and hoped to enjoy even greater public recognition by going after many of the rich and powerful on Wall Street. With Milken now the most prominent name in corporate takeovers, he was Giuliani’s ultimate target. If anyone was to be identified as the central figure in the “complex network of information” that was purportedly costing American jobs and perverting high finance, it was Milken.

The path to a Milken prosecution, however, was not direct. It started with New York–based Drexel investment banker Dennis Levine and none other than arbitrageur Ivan Boesky. Levine worked on Drexel’s mergers and acquisitions business and therefore was in a position to trade on inside information. He made a great deal of ill-gotten money by buying and selling stocks of his clients based on confidential information. He also sold his privileged information to Boesky, who used it to turn large profits for his merger arbitrage accounts. So when Giuliani nabbed Levine—thanks mainly to the SEC’s investigative efforts—he negotiated a criminal plea agreement that reduced his likely jail time if he could offer testimony useful in indicting Boesky.

After receiving a subpoena in August in connection with his dealings with Levine, Boesky caved quickly. He entered into his own plea agreement in September with Giuliani. Boesky, like Levine, agreed to provide testimony to aid in the prosecution of another suspect—and that suspect was Milken, the end target from the start of Giuliani’s Wall Street crusade. In exchange for his full cooperation in indicting Milken—including wearing a wire in meetings with him and allowing the recording of their phone conversations—Boesky was allowed to plead to only one felony count of insider trading. On November 14, 1986 (a day that became known on Wall Street as Boesky Day), Giuliani proudly announced the government’s deal with Boesky. At Boesky’s sentencing shortly afterward, the government followed through with its leniency, handing down a three-year sentence and $100 million fine, both just half the penalty called for by the single offense to which he pleaded guilty.

By the time the Wall Street prosecutions reached Milken in 1989, both Giuliani and the SEC had already taken action against Drexel, with the bulk of their charges revolving around the $5.3 million payment from Boesky to Drexel. In his prosecution of the firm, Giuliani hauled out his ultimate weapon, charging that Drexel was a “racketeering enterprise.” That meant that under the provisions of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) the government could freeze Drexel’s assets at the time of indictment—before any conviction. In the same spirit, Giuliani demanded that Drexel fire Milken if he were indicted—again, before Milken was actually convicted or pleaded guilty. Fred Joseph, by this time Drexel’s CEO, knew that no investment firm could operate if its assets were frozen and also knew that Milken’s indictment was a near certainty. So in December 1988, Drexel pleaded that it was “unable to contest” the government’s charges (a guilty plea in gentler terms) and settled the government’s lawsuit, paying a record-setting fine of $650 million and firing Milken. In reality, Joseph’s decision to cooperate with the government only prolonged the agony and Drexel declared bankruptcy in early 1990.

Between Drexel’s guilty plea and its ultimate collapse, Giuliani’s investigation continued with the obvious mission of indicting Milken. There were a few vocal Milken supporters—one of them memorably stating, “Corporate America is hoping to indict Mike Milken so it can go back to sleep for another thirty years.”22 But in the main, public opinion was decidedly not in Milken’s favor. It was the tail end of the “decade of greed,” and Milken, rightly or wrongly, had become its most visible symbol. The savings and loan industry was collapsing as a result of high interest rates and inept management. The U.S. government had authorized thrift institutions to buy high-yield bonds just a few years earlier, and Milken became a convenient scapegoat for that crisis as well, with allegations that he foisted worthless bonds on unsuspecting savings institutions—although junk bonds never accounted for more than the 1 percent of S&L assets and the Government Accounting Office testified that the bonds had no role in the crisis.23

In March 1989, at the height of anti-Milken sentiment, the U.S. attorney, as expected, handed down a massive indictment against both Michael Milken and Lowell Milken. While the same New York office had allowed Boesky, its prime witness, to plea to a single count, its ninety-eight-count indictment threw the book at the Milken brothers. The charges included insider trading and various forms of fraud, but most alarmingly for Michael and Lowell, it alleged violations under RICO. If they were convicted of the indictment’s charges at trial they would face many decades behind bars—housed with an unsavory group of traditional RICO convicts.

The most newsworthy revelation from the 1989 indictment was not the long list of alleged crimes or even the RICO charges, but rather, on the second page of the indictment document itself, the fact that Drexel paid Michael Milken $550 million in the prior year. It was an unprecedented amount, greater than any business executive had ever made. As a prosecutorial tactic, it served to establish that Milken was indeed the personification of greed.

Faced with the multicount indictment, Milken’s first impulse was to go to trial and take his chances with a jury. Unlike most defendants prosecuted in federal court, he could easily afford to hire an all-star team of criminal lawyers to refute each and every one of the government’s ninety-eight charges. But the reality was that prosecutors would have at their disposal a growing cast of witnesses to testify before the jury as to Milken’s guilt, not just Boesky, but many others from Drexel who had turned state’s evidence to protect themselves in connection with the firm’s prosecution.

Given all this, Milken’s lawyers realized that a conviction at trial was highly likely with the result that Milken would be incarcerated for the better part of his remaining years. In addition, the government indicated that it would drop the charges against Lowell if Michael Milken, the true target, entered into a plea agreement. Perhaps most difficult to overcome at trial would be the $550 million compensation. The jurors may have never heard of the nineteenth-century writer Honoré de Balzac, but at some gut level they too were likely to feel that, as Balzac famously put it, “Behind every great fortune lies a great crime.” Ultimately, following the advice of his lawyers and their counsel that “only religious fanatics believe they have to go to trial,”24 Milken pleaded guilty to six relatively minor counts of criminal behavior, none of which involved racketeering or insider trading. Unsurprisingly, four of the six counts involved his dealings with Boesky and Posner and the $5.3 million payment.

Mixed Verdicts

Milken was certainly avaricious beyond any normal limits, and it’s clear that his pursuit of ever-higher markers of success clouded his judgment, but whether he engaged in actual criminality remains a subject for debate. His detractors tend to cling to the “evidence” that anyone who could become so wealthy at such a young age must be doing something illegal. His supporters, believing Milken was a political pawn, liked to point out that the offenses to which he ultimately pleaded guilty were mere technicalities and committed every day on Wall Street’s trading desks. The truth is probably somewhere in between and certainly more nuanced, but the comment attributed to business writer Michael Lewis may be apt: “Mike Milken was convicted of loitering in the vicinity of the savings and loan crisis.”

At sentencing, Milken was ordered to ten years of confinement. That sentence was reduced shortly afterward to just twenty-two months in light of “substantial cooperation” with the government in later cases. But there was little that Milken testified to of any importance, and most observers believe the very large sentence reduction reflected the judge’s reconsideration of the penalty in light of the substance of the case. When stripped to its essentials, Milken was convicted primarily of stock parking, an offense for which no one had ever before gone to jail.

Despite the controversy his career generated, the effect that he had upon the financial world was irreversible and monumental. In his twenty-year stint with Drexel, he had transformed the way businesses raised money and he had created a widely accepted financial instrument called a junk bond. Beginning with Milken’s one-man operation, trading in a corner of the New York office of Drexel Harriman Ripley, the high-yield market has expanded to thousands of corporate issuers. During Drexel’s collapse and Milken’s brief imprisonment, new junk bond issuance slowed to a trickle, and many were predicting a total collapse of Milken’s “Ponzi scheme.” But several Wall Street firms quickly took up the slack, most notably Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette. As a result, the market value of all outstanding junk bonds has increased from about $150 billion when Milken went to jail to approximately $1.5 trillion today.

Books and articles that appeared during and after his tenure seem evenly split between naming Milken the devil incarnate or, alternatively, the savior of modern finance.25 But few would argue that he conforms to the typical vision of an ex-con—especially an ex-con with several hundred million dollars at his disposal. He still lives in an unpretentious house in Encino, not far where he met his first and only wife. He still drinks no alcohol or caffeinated drinks and in manner, physique, and dress could pass for a somewhat intense high school science teacher—who might double as the track coach.

In her sentencing memorandum to the court, his probation officer Michalah Bracken captured the essence of Milken as well as anyone:

Among Milken’s strengths are his inability to accept defeat, his total commitment to causes he considers “just and right,” and his vision concerning business and society. His weakness was that, as creator and head of the High-Yield Bond Department at Drexel, these convictions were more important than his responsibilities and obligation to conduct business fully within the parameters of the law. Yet, despite his fall, Milken is an individual still able to contribute to society and to create positive changes in the future.26

Bracken was correct in her opinion about Milken’s future contributions. The former financier is now an entrepreneur for philanthropy, putting his considerable money, energy, and intellect into new ventures in medical research, education, and social causes. Based on his initiatives in healthcare, Fortune called him “The Man Who Changed Medicine” in a 2004 piece that described Milken’s help in speeding up and improving cancer research. (The focus on cancer is personal; Milken contracted prostate cancer at about the same time he was freed from prison.) His pace in later life appears to be as frenetic as it was on the trading desk at Drexel, with one of the cancer researchers he works with complaining to the Fortune reporter that Milken “is exhausting—physically, mentally, and emotionally exhausting.” Even Rudolph Giuliani, Milken’s onetime nemesis and also a prostate cancer survivor, told Fortune, “I realize now that I didn’t know him then. The man I now know is able to do tremendous things. He took the tremendous talent he had in business and is using it to fight prostate cancer. What more could you ask for?”27