9

Squadron Leader Tony Spooner, a much-decorated pilot and veteran of numerous perilous flights over the Atlantic and Mediterranean, wrote a poem that reflected the feelings of many of his comrades who served in Coastal Command.

Fighters or Bombers? his friends used to say

But when he said ‘Coastal’ they turned half away …1

The lines were often read at veterans’ funerals, and the title – ‘No Spotlight for Coastal’ – seemed to sum up the unconsidered place they occupied in the war years; in the RAF’s order of priorities, in the minds of the government and in the imagination of the British public.

It was Coastal Command’s fate to be third in line for everything – resources, money, glory and attention. It operated far away from the public gaze and the nature of the work was repetitive and unglamorous and therefore harder for the propaganda factory to package. Yet its role in Britain’s survival was at least as important as that played by Fighter Command, and its contribution to victory as significant as that of Bomber Command.

Unlike the others, it started the war lacking a clear role and simple, agreed objectives. It would take several years and much trial and error before its proper function became obvious and its squadrons were equipped with the right machines and technology to carry out their duties. The delay did not mean there was any slackening in the work rate. ‘Constant Endeavour’ was the motto given to Coastal Command, and it could not have been more appropriate.

The confusion over role and identity was partly the result of the Air Force’s fractious and complicated relationship with the Navy. The Admiralty had never accepted the arrangement arrived at in 1924 by which aircraft and crews operating on Navy ships belonged to the RAF. In 1937 a compromise was reached in which control of all carrier-borne aircraft was returned to the Navy under the aegis of the Fleet Air Arm.

The deal did nothing to remove the fundamental incompatibility in the outlook of the services. At heart, the Admiralty continued to believe that logic and justice demanded that they should exercise full control over all air resources that directly affected the Navy’s operations. The RAF, meanwhile, feared that ceding the principle would undermine, perhaps fatally, its hard-won status as an independent service.

The picture was made cloudier by prevailing strategic assumptions about how the war at sea would play out. The old charge that soldiers were always fighting the last war did not apply to the Admirals. Their plans and hypotheses suggested they had entirely forgotten it. Much of the naval effort in 1914–18 had gone into protecting the transatlantic sea lanes on which Britain relied for its survival. The main threat had come not from the powerful German surface fleet, which was neutralized after the Battle of Jutland, but from U-boats which in 1917 sank 6.6 million tons of Allied shipping, seriously weakening the country’s ability to continue the war.

The danger had been overcome by a system of merchant convoys, protected by escorts armed with guns, depth charges and torpedoes. By then aircraft, too, were playing an important part and in November 1918 the Air Force had 285 flying boats and 272 land-based aircraft engaged in hunting U-boats. They managed to sink only seven enemy submarines but the deterrent effect was strong. The Naval Staff came to believe that ‘the ideal was that a convoy should be escorted by at least two aircraft, one keeping close and one cruising wide to prevent a submarine on the surface from getting into a position to attack’.2

By the time the war started the wisdom had changed. Thanks to the development of ‘Asdic’, anti-submarine underwater detection, the Navy believed it could handle the threat without any need for heavy air support. Its main concern at the beginning was not the U-boats but the Kriegsmarine’s squadrons of fast, heavily armed and long-ranging capital ships and pocket battleships which, once at large in the Atlantic, could savage Britain’s supply lines.

So it was that in the joint discussions to design a co-operative air and sea organization, held between the Admiralty and Coastal Command, the emphasis was on defensive and passive tasks. The prime duty was to be reconnaissance: ‘to assist the Home Fleet in the detection and prevention of enemy vessels escaping from the North Sea to the Atlantic’, that is, the dreaded breakout of the surface fleet.3 Next came the provision of air patrols to spot submarines and convoy escorts to scare them off in British coastal waters. Offensive operations were last on the list, the ‘provision of an air striking force’ and then ‘mainly on the east coast’.

Despite the history of institutional wrangling, at the outset personal relations between Coastal and the Navy were good. Its chief, Frederick Bowhill, was a former sailor with ‘sea water in his veins’ who joined the RN in 1904, transferred to the RNAS in 1913 and started the First World War commanding the Navy’s first aircraft carrier, HMS Empress, a converted cross-Channel ferry. He was no one’s idea of a seadog, nor indeed of an aviator, with a bald pate, bulging eyes and shaggy red eyebrows that swept upwards across his forehead as if about to take flight. According to his successor Philip Joubert, the fierce impression they gave belied a ‘puckish humour that solved awkward problems of prestige and smoothed ruffled sensitivities’ – useful qualities in the circumstances.4

Joubert believed that Bowhill’s ‘wide knowledge of seafaring matters and his long experience in the flying service made him very well fitted to the control of the sea communications in war’. As a result he commanded the respect of the Navy. His successors, including Joubert himself, ‘were not so fortunate. All of them had Army origins and as such were suspect …’ Nonetheless, though they might lobby persistently for greater air resources, the Admirals did not exploit wartime crises to pursue old claims. When, in the autumn of 1940, Lord Beaverbrook saw an opportunity to stir trouble with a dramatic proposal for Coastal Command to be handed over wholesale to the Navy, it was the opposition of the First Sea Lord, Dudley Pound, that effectively sunk the idea.

Joubert’s one – inaccurate – criticism of Bowhill was that he harboured ‘a grave suspicion of all scientists, and their works’. Service chiefs got used in wartime to being assailed by experts lobbying for a new gizmo that would supposedly win the war. Most of the innovations were useless but some did indeed turn out to have transformational powers. The breakthrough in the development of British radar, after all, emerged from initial research to test the validity of a ‘death ray’ that would kill the crews of hostile aircraft.

Joubert prided himself on understanding the crucial part that science would play in the war at sea, a struggle that Coastal Command would be in the thick of. Despite the Navy’s initial breezy confidence, it would turn out to be just as much a life and death affair as the Battle of Britain, yet it would go on for years rather than months. The Battle of the Atlantic was waged in various forms from the first day of the war. Though a discernible turning point was reached in the middle of 1943, the U-boat menace persisted and the effort to protect the Allied oceanic supply lines by sea and air continued right until the very end. Everyone who mattered understood the immensity of the stakes. Yet there was never a systematic policy emanating from the government, or even from the Air Ministry, to give Coastal what it needed.

The struggle to keep the sea lanes open had many ups and downs. At the break of each false dawn there was a tendency to scale back the resources of the maritime air effort and divert them to other theatres. There was a perpetual clamour for men and machines from all branches of the service, but, with the bomber credo so deeply entrenched in the minds of the Air Marshals, it was Bomber Command’s claims that carried the most weight.

At the start of the war the aircraft, armament and technical equipment with which Coastal Command was equipped were all pathetically inadequate for the tasks it was set. The situation would only get worse as the range of their duties grew ever wider. It was just as well that, at the beginning, its main responsibility was reconnaissance rather than offensive operations.

The Air Ministry issued specifications for a twin-engine reconnaissance/bomber in 1935. Two types were approved but one, the Blackburn Botha, turned out to be all but useless. At the outbreak of hostilities, Coastal’s striking power rested on the frail shoulders of the Vickers Vildebeest, a lumbering, antediluvian biplane. Seaplanes were an essential element in the armoury, extending operational capacity to geographically difficult parts of the world and greatly reducing infrastructure needs. The excellent Sunderland, which carried a crew of thirteen, bristled with ten machine guns, had a range of nearly 3,000 miles and could stay airborne for more than thirteen hours, was due to be phased out and replaced with the Lerwick, another Short Brothers design. Like the Botha it proved to be a dud but when, in the spring of 1940, the Air Ministry turned again to the Sunderland, Short’s Belfast factory was at full capacity churning out Stirlings for Bomber Command. Thus, Coastal’s flying boat fleet in 1939 was supplemented by antique-looking Saro Londons and Supermarine Stranraers.

The unpreparedness of Coastal Command seems reprehensible now but it is easy to forget the enormous hurry in which the RAF went to war and the vast array of problems all services – but particularly the Air Force and Navy – faced with only limited resources from which to contrive solutions. There was not just a nation but an empire to defend and not one potential enemy but three, as Italy and Japan hovered opportunistically on the side lines. What is harder to justify was the later reluctance at the top of the Air Force to make a more intelligent use of available assets when it was clear that the Battle of the Atlantic was as crucial a struggle as the Battle of Britain had been.

New machines were on their way in the shape of Bristol Beaufort torpedo bombers, a happier result of the Air Ministry’s 1935 specification, and 200 Lockheed Hudsons, ordered from the US in 1938, largely on the initiative of Arthur Harris against the furious opposition of the domestic aviation industry lobby. Until then, Coastal’s backbone consisted of the ten squadrons equipped with Avro Ansons, a converted six-seater civilian passenger plane. The aircraft’s reliability was reflected in its nickname, ‘Faithful Annie’. Tony Spooner thought the ‘dear, safe, wallowing Anson … possibly the most viceless aircraft ever designed’, but there were several crucial downsides.5 It was slow, dangerous in violent manoeuvres and so short ranged that it could not get to the Norwegian coast – a vital area in the maritime war – and back. Guy Bolland, who in 1940 commanded Coastal’s 217 Squadron, felt they were ‘quite useless in any wartime role except a limited anti-submarine patrol to protect shipping’.6

At this stage, the mere sight or sound of any aeroplane was enough to cause any U-boat which had surfaced in order to vent the stale air from its hull and recharge batteries to make an immediate dive to safety. Tiger Moths, the game little biplane trainers that every RAF pilot knew from his basic training, were pressed into service on these ‘scarecrow’ patrols. The disruption they caused was valuable, but the German submarines had little to fear. According to Bolland, the Anson was ‘both too slow and too fragile. The engines had to be started up by using a starting handle … Its undercarriage was retractable but only after the use of another (collapsible) handle which took many turns to retract it after take-off and to lower it for landing. For waddling along from A to B it was fine, but the performance, bomb load and armament were totally inadequate and it was soon to be taken off front line duties.’

Bolland joined the RAF on a short service commission in 1930 after a career at sea as a junior officer in the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company. He transferred to Coastal on its creation and commanded the station at Pembroke Dock before taking over 217 Squadron in August 1940 and was by all accounts a popular and efficient commander.7 The story of his time in charge gives a taste of the demands and hardships common to many of the command’s squadrons in the first phase of the war.

217 was based at St Eval, a hurriedly constructed station on the north-west Cornwall coast, and was mainly involved in flying anti-submarine patrols over the Western Approaches to the Channel. The unit was in the middle of re-equipping with the Bristol Beaufort, a much more impressive aeroplane. Its twin Taurus engines made it the fastest torpedo bomber of the day and it was reasonably well defended with a machine gun in the wing and two mounted in a dorsal turret. The transition was difficult. Beauforts were much harder to fly than the placid Annie. In the meantime, operations with Ansons continued.

With the arrival of German U-boats, followed by large surface warships, in the French Atlantic ports the scope of the squadron’s work had widened. The Kriegsmarine now had direct access to the Atlantic sea lanes and the Admiralty inundated the RAF with demands for bombing raids on the ports of Brest, Lorient, La Pallice and Bordeaux. Bowhill responded willingly and Coastal squadrons were diverted into pinprick raids aimed at stalling the gathering threat.

Bolland’s predecessor, Wing Commander L. H. Anderson, who had arrived on the squadron on I July 1940, was dismayed at the new orders. The Ansons with their fixed, forward-firing .303-in.-calibre machine guns, were laughably easy targets for the four squadrons of Me 109s defending the port. Their payload of four 100lb bombs would do little significant damage if by any chance they managed to deliver them. When, in mid-July, Anderson was told to launch a daylight raid on Brest, he refused to sacrifice his men in what he saw as a pointless exercise. He was removed from his command and, at a court martial in October, reduced to the rank of squadron leader.8

If Bolland’s superiors believed that he would be more biddable they were soon disappointed. One of his first acts was to fit Vickers ‘K’ machine guns in the waist of the Ansons to provide them with a little added protection. However, when this reached the ears of Group Headquarters in Plymouth he was told that the modification was unauthorized and the guns would have to be removed. ‘This was an order which I did not obey,’ he recorded.

Bolland found that ‘squadron morale was very low’. One of the factors determining a unit’s state of mind was the degree to which its members felt that their actions made some contribution, no matter how small, to the war effort. The business of going back and forth over vast grey wastes of water, while struggling to keep fatigue and boredom at bay, often to return having seen nothing, did not bring any sense of achievement. Bolland wrote that after the war U-boat commanders ‘made it plain in their memoirs how much they feared the mere sound of an aircraft and just the possibility of being seen’, causing them to dive and disrupting their pursuit of their victims. However, ‘those facts were not known to us at the time and it [was] impossible to persuade many of those who flew thousands of miles without a sight of the enemy that they were doing [anything] to win the war’.

Life on the ground that winter was unsettling with constant air raid warnings and occasional bombs landing on and around the base from raiders on their way back from plastering Merseyside. On 21 January 1941 a parachute mine landed on an air raid shelter, killing twenty-one of the base ground staff.

While the Beauforts were bedding in, Ansons kept up attacks on the Atlantic ports. When operating in darkness the fighters left them alone and they escaped relatively unscathed by flak so that in 200 sorties not a single aeroplane was lost. The crews noticed that the shells always seemed to burst some way ahead of them and concluded that they owed their survival to the fact that German gunners did not realize that the attacking aircraft were so slow and made a correspondingly exaggerated guess at the degree of deflection needed to hit them. Better aircraft only brought heavier casualties. In December 1940, the first month of night operations by the Beauforts, six machines and eighteen crew members were lost; this out of a squadron with a nominal strength of eighteen aircraft.

Admiralty pressure on the Air Force intensified with the appearance of the German battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau in Brest in the early spring of 1941. They had joined the U-boats and the long-range Focke-Wulf 200 ‘Condor’ maritime patrol and bomber aircraft in ravaging the Atlantic traffic, sinking 115,622 tons of shipping during their voyage south. They were constrained by the fact that they did not have the guns to tackle convoys which sailed with a battleship escort. That deficiency would be remedied with the arrival of their own battleship, Bismarck, which had finished its final sea trials and was due to dart through the northern seas to join them. The worsening situation brought a new call to arms from Downing Street. On 6 March 1941 Churchill issued his Battle of the Atlantic directive which ordered all available resources to ‘take the offensive against the U-boat and the Focke-Wulf wherever we can and whenever we can’. When the German cruisers were confirmed as having docked at Brest on 22 March, an all-out air assault by Bomber and Coastal Commands began.

217 Squadron had already been involved in the effort to sink the cruiser Admiral Hipper which arrived at Brest in mid-February after two successful Atlantic sorties. The order to attack the port would trigger the premature departure of a second CO. Guy Bolland recorded how ‘one day in March … I had orders to send available aircraft to raid [Brest] in daylight. I was only too well aware how well-defended that was by guns and fighters. There was no possible chance of any of my machines getting anywhere near Brest, and if they were lucky enough to hit the ships, the damage they inflicted on the enemy would be negligible.’ The chances of disaster were further increased by the fact that there would be no fighter escort to offer any protection over the target. He decided to take the drastic step of declaring that all his aircraft were unserviceable. Group Headquarters in Plymouth were immediately suspicious and queried the signal. Bolland recalled that ‘as the day wore on C-in-C Coastal Command [Bowhill] came onto the phone demanding that I got some aircraft serviceable. The station commander at St Eval was not supporting me and I was out on a limb.’

Such was the pressure that he relented enough to make three Beauforts available, bypassing the station commander to warn Plymouth that ‘this was a suicide order and I was dead against it as it would serve no useful purpose except to pander to the Navy’s demand for action’. He told the Air Officer Commanding 19 Group, Air Commodore Geoffrey Bromet, ‘that I did not expect to ever see any of my crews again and if this turned out to be true, to expect to see me in Plymouth that night’.

All three Beauforts were lost with only one of the twelve crew members surviving. Bolland kept his promise, turning up at the headquarters at Mount Wise that evening where he bearded Bromet and an unnamed senior naval officer. ‘I told them as clearly as I could that the order to send young men to their deaths on useless missions was not on, and I did not think they could possibly understand what the defences of Brest were like.’ He signed off with a suggestion that must have burned like acid: ‘Perhaps it would be better if I could discuss this with someone on their staff who had fought in the war.’

For this insubordination Bolland was duly sacked. Unlike Anderson he was not subjected to court martial, and somewhat to his surprise found himself posted to the staff of the Commander of the Home Fleet, Jack Tovey, as Fleet Aviation Officer, handling liaison between the admiral and Bowhill.

The diversion of attacking ports did bring some results, in one case spectacular success. Bomber Command led the assault on the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau at Brest but it was a Beaufort of Coastal’s 22 Squadron that did the most significant damage. On the morning of 6 April 1941, Gneisenau lay in the port’s inner harbour having been moved there from dry dock the previous day due to the presence of an unexploded bomb delivered in an earlier RAF attack. The new position was spotted by a Spitfire from the Photographic Reconnaissance Unit and a strike ordered for first light.

Of the four Beauforts in the attacking force, only the one piloted by Flying Officer Kenneth Campbell managed to locate the target in the morning haze. Coming in low from seaward he would have seen before him, first, three flak ships bristling with anti-aircraft guns, then behind them a low stone mole that ran in from the west to curve protectively around the dock and five hundred yards beyond that the low bulk of the battlecruiser, hard up against the north wall of the harbour. More guns were clustered on the slopes behind the town, and other batteries sat on the two arms of land encircling the outer harbour. Within seconds of the Beaufort appearing every gun – a thousand weapons of all calibres – was in action. To hit the ship, Campbell had to drop his single torpedo just the other side of the mole. According to the official report ‘coming in at almost sea level, he passed the anti-aircraft ships at less than mast height in the very mouths of their guns, and skimming over the mole, landed a torpedo at point blank range’.9

At that height and speed, he had no chance of clearing the high ground ahead and hauled the aircraft into a tight turn, thus presenting an unmissable target. The Beaufort plunged into the harbour in flames, but the torpedo ran straight and true, exploding beneath the Gneisenau’s waterline. The attack was followed by another Bomber Command raid five days later, which killed many of the crew, and it would be eight months before the battlecruiser was seaworthy.

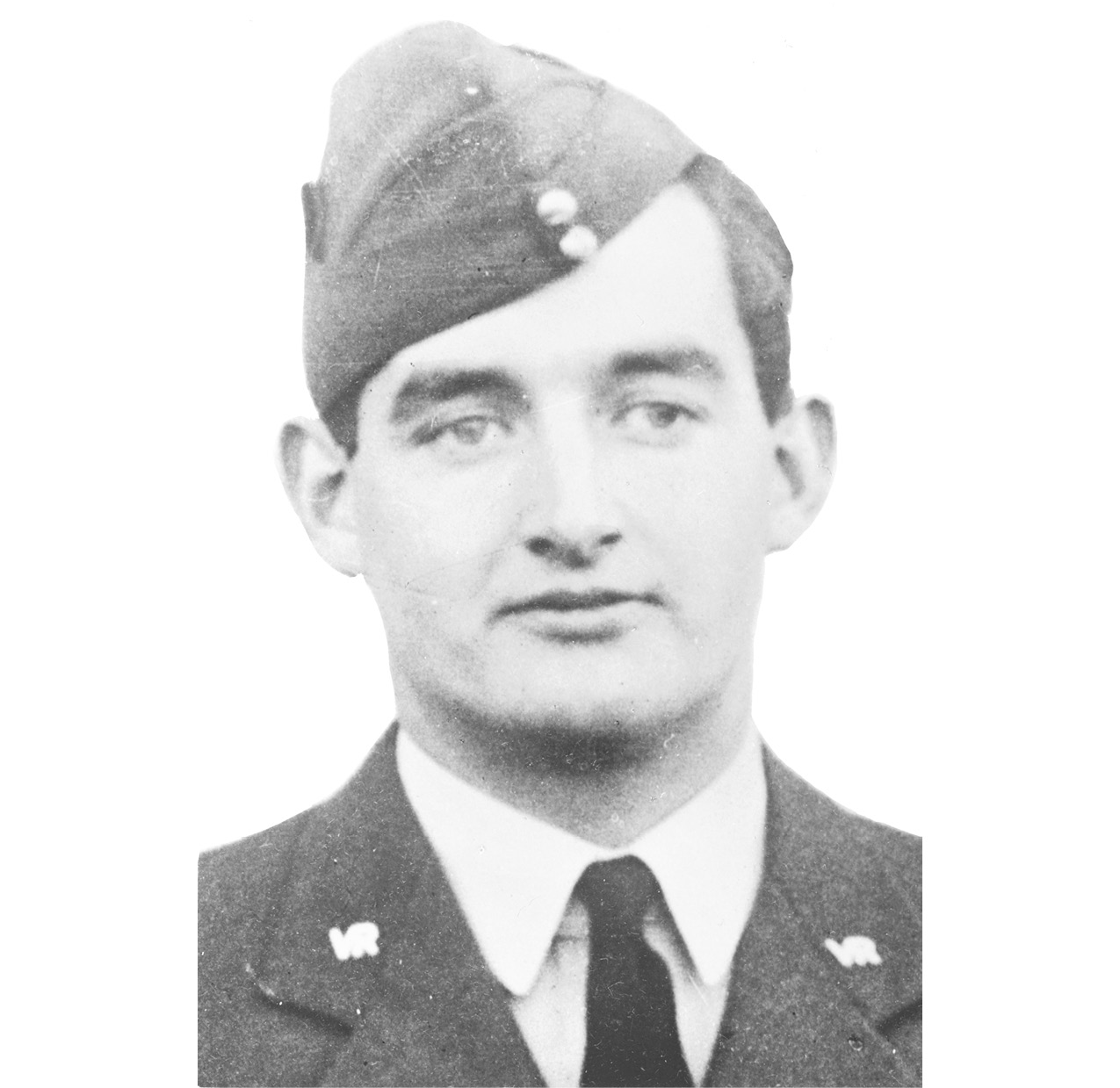

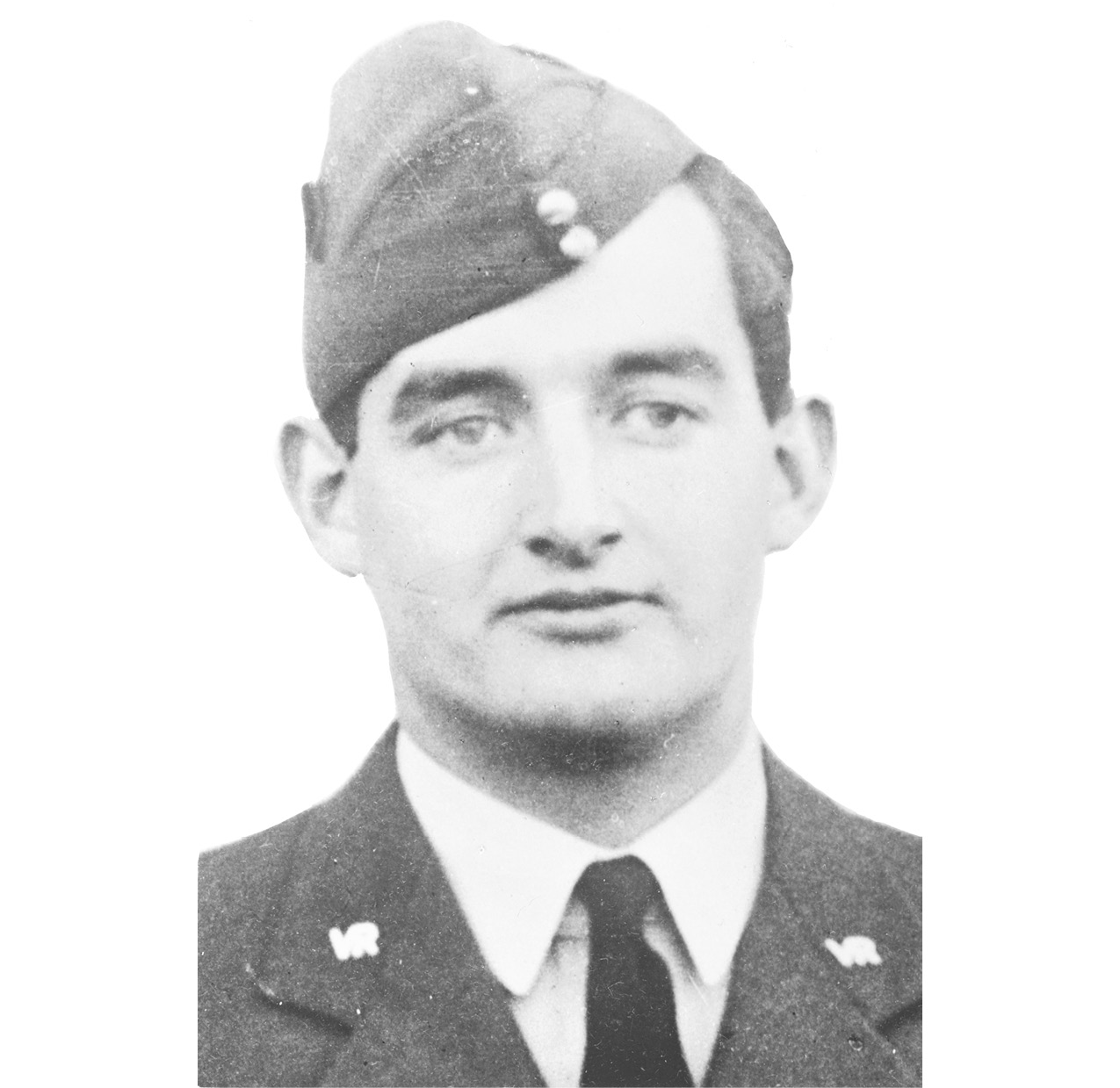

Kenneth Campbell VC (© Imperial War Museums, CH 4911)

Campbell, of course, was dead, along with his crew, Sergeants J. P. Scott, the Canadian navigator, R. W. Hillman, the wireless operator, and W. C. Mullins, the air gunner. As the pilot and captain, Campbell was awarded the Victoria Cross. The others, in keeping with the practice of the time, were deemed to have played no part in the decision to press home the attack and got nothing. Campbell was a twenty-three-year-old Scot, born in Saltcoats, Ayrshire, educated at Sedburgh public school and Cambridge where he read chemistry and joined the University Air Squadron. What drove his extraordinary determination, what armoured him from the paralysing fear that the eruption of gunfire that met them must have provoked, we shall never know. In the photograph, from beneath his Air Force Blue side cap his steady eyes meet ours and tell us nothing.

The great Atlantic rendezvous of German surface ships never happened. In May, the attempted breakout by Bismarck came to a spectacular end when, after being battered by the shells and torpedoes of a combined naval task force, she went down 500 miles off Brest, with all flags flying. The episode provided some much-needed good news but also demonstrated that, used intelligently, combined air and sea operations could be devastatingly effective. Coastal played a crucial part in the battleship’s demise. It was a Spitfire from the command’s No. 1 Photographic Reconnaissance Unit, which on 21 May took the pictures from which Bismarck and its consort, Prinz Eugen, were positively identified as they steamed towards Bergen.

The following day a Fleet Air Arm Maryland dipped below the clouds blanketing the Bergen fjords to establish that they had now departed. Both Coastal and FAA reconnaissance aircraft dogged the battleship’s steps as it passed through the Denmark Strait between Greenland and Iceland, and carried on the pursuit following the action of 24 May in which HMS Hood was sunk. When Bismarck shook off its shadowers on 26 May, it was a bold stroke by Frederick Bowhill that put them back on the trail. He ordered a patrol further south than the Admiralty reckoned the quarry to be. Coastal Command Catalina flying boats intercepted the battleship nearly 800 miles north-west of the haven of Brest and set in train the FAA Swordfish attack that slowed, and ultimately doomed, the battleship.

By now it was clear that the role allotted to Coastal Command at the outset was not ambitious enough. Its aircraft and crews would be better employed not just in reconnaissance and deterrent patrols but in an offensive role, hunting U-boats and destroying them.

The arrival of more and better aircraft and upgraded radar meant they were in a reasonable position to combine with the Navy to provide improved protection for the convoys and take the fight to the Germans.

Bowhill left in June 1941 to take over Ferry Command. On his watch, Coastal had undergone a quantitative and qualitative transformation. The nineteen squadrons it had started the war with had grown to forty. New aircraft like the US-manufactured PBY-5 Catalina seaplanes were almost as big as the Sunderlands and could operate 800 miles from base and stay in the air for seventeen hours. The flying boats were relatively spacious compared with most military aircraft but there was ‘still less room in which to move than is to be found in a small fishing smack’.10

The Lockheed Hudson could be projected 500 miles with a time over the target area of two hours. Wellingtons and Whitleys ceded by Bomber Command could also spend two hours on station at that distance. The basing of a wing in Iceland in the late summer of 1940 opened the air umbrella wider, though a gap in mid-ocean still remained which could not be covered from either side of the Atlantic. There were some, though still not enough, long-range fighters to offer a degree of protection from the Condors and long-range Heinkels that reinforced the air offensive.

The men who flew the patrols had an identity which set them slightly apart. A disciplinary report noted that Coastal was ‘a more stable command. The captains have earned their rank by long experience, and the crews as a whole are a more reliable and responsible type.’11 Tony Spooner fitted the approving stereotype. In 1937 he had decided to try and become an airline pilot. The attraction was the pay and career prospects rather than any romantic attraction to flying. He had been an instructor before joining Coastal and had a strictly methodical approach to operations.

Steady types were needed in this unglamorous front of the air war. The report noted ‘the isolated nature of many of the stations’, far from the bright lights. Early in 1941 Spooner was based at Limavady, in Northern Ireland. The station was next to Lough Foyle, and he was able to vouch for the truth of the local saying that ‘if you can see across the lough it’s a sign that it’s about to rain. If you can’t, then it’s raining already.’12

The work was tedious. As an official publication of the time put it, ‘the chief enemy is not the German Luftwaffe or the German Navy, but boredom, which may provoke first inattention, then indifference. [The pilot] must spend hundreds of hours with nothing to look on but the expanse of sea and sky. “Wave, on wave, on wave, to West” stretches the vast monotony of the Atlantic Ocean. It may glitter in the noonday or lie devoid of light and colour in the hour after sunset; it may seem to crawl like the wrinkled skin of a beast or stretch in ridged and uneven furrows under the breath of strong winds; but it will be empty for hours.’13 Protracted staring at the sea could prove fatal, sending the pilot into a trance and blinding him to the line between sky and water.

When disaster struck, as it all too often did, it was most likely to be caused by accident or error. It was hard to know, as the end came out of sight of ship or aircraft, witnessed only by the seabirds. On beginning his tour of operations with 221 Squadron flying Wellingtons over the North Atlantic, Tony Spooner noted how ‘most of the losses remained unexplained … crews went out and simply “failed to return.” Perhaps an engine failed? Perhaps they got lost? Perhaps they flew into the sea deceived by their altimeters? Perhaps they got iced up, or ran out of petrol fighting engine ice?’14

The latter was a major hazard, ‘our great enemy’. Whenever possible they tried to fly below the cloud base where icing was less likely, but when the weather made this too dangerous, they were forced to climb into the colder upper air. A chemical de-icing agent could offer protection to the wing and tail surfaces but rain soon washed it off. Propellers collected ice easily, as did the carburettor intakes of the engines. The drill in the case of the former was ‘to make violent alteration in the revs per minute hoping to dislodge [it] by vibration and centrifugal forces’. In the latter it was to ‘either try a full-power climb through the cloud to the clearer air on top or, as a last desperate remedy … switch the ignition off – then on; the monumental back fire which resulted would with luck, clear the carburettor throat’. There was nothing they could do, though, to prevent ice encrusting the aerials which festooned their Wellingtons, emitting an eerie singing noise as they vibrated.

It seemed to Spooner that enemy action was the least likely explanation for disappearances, partly because it was obligatory to send an immediate ‘ops flash’ signal as soon as a hostile aircraft or vessel was sighted. A more dispiriting reason was ‘the sad fact … that neither 221 nor 502 Squadrons, [the sister unit] were finding the enemy, except on very rare occasions …’ Even if they did spot a U-boat, ‘it usually was able to dive under the waves before the crew could drop their load of depth charges’. The figures bore out this judgement. In the first twenty-two months of the war, Coastal Command aircraft spotted 161 U-boats and attacked 125 of them. They managed to sink only two, and then with assistance from Navy craft.15

Philip Joubert took over command from Bowhill in June 1941 and, according to the official historian, made it his first task to ‘develop the most effective operational technique for ASV aircraft, and in so doing to make the aeroplane at last a “U-boat killer”’.16 ASV stood for air-to-surface-vessel radar, supposedly capable of locating U-boats on the surface and with a forward scan of twelve miles and a side scan of twenty. In its early forms, however, it was mainly of use as a navigational device, rather than as a means of pinpointing enemy submarines, and when the government’s chief scientific adviser Sir Henry Tizard visited Limavady and asked the crews how many U-boats they had detected with it the answer came back ‘none, or possibly one’.17

Fighting submarines was a mechanical, methodical business. The battlefield was vast, ten and a half million square miles of sea. The northern boundary lay inside the Arctic Circle and the southern on the Equator. It stretched in the east to the coasts of western Europe and West Africa, and in the west to the eastern seaboards of Canada, Newfoundland, the USA and Central America.18 Finding U-boats in this wilderness meant catching them while they were leaving or returning from a hunting sortie, or as they tracked, or lay in wait, for a convoy. German cryptanalysts had partly penetrated the Navy’s codes before the war began and also cracked those used by merchant shipping, which greatly helped the Kriegsmarine’s commander Admiral Dönitz deploy his forces to maximum effect.19 Much of Coastal’s effort went into flying patrols in likely areas. This involved criss-crossing a designated grid for as long as the weather and fuel allowed until the ‘Prudent Limit of Endurance’ was reached.

If sighted, the patrolling aircraft had to get its attack in quickly for an alert commander could dive his boat in thirty seconds. On board the aircraft, a klaxon sounded action stations and bombs and depth charges were primed. There was often little to show for a successful operation except some mysterious debris. One report of an attack by a Sunderland 210 miles off Finisterre described how ‘bombs were dropped within twenty feet when the submarine was at periscope depth and a large oil patch with air bubbles was observed. Later more bubbles appeared in the centre of the patch. After twenty minutes the oil patch extended with bubbles continuing to rise. The aircraft remained in the vicinity for three and a half hours …’20

The crew of a Hudson, sent out from Iceland on 27 August 1941 after a patrolling aircraft from the same squadron attacked but failed to sink a U-boat, had the satisfaction of catching it just as it surfaced again. After it dropped depth charges ‘the U-boat was completely enveloped by the explosions and shortly afterwards submerged completely’.21 Two minutes later it reappeared and ‘ten or twelve of its crew wearing yellow life jackets appeared on the conning tower and came down on deck’. The Hudson dived, ‘firing all its guns it could bring to bear as it swept in tight turns around the submarine’. The crew then scrambled for the conning tower, re-emerging seven minutes later waving a white cloth, subsequently discovered to be the captain’s dress shirt. Relays of aircraft then kept watch for eleven and a half hours until a naval trawler arrived to capture the prize.

The increasing success of the campaign was due to the greater number of better machines available, the improved quality of radar and the greater efficiency of depth charges, bombs and rockets. None of these were obtained without a struggle. Once again, the peculiar relationship that Coastal Command stood in, not just with the Navy but with the RAF itself, created special difficulties when it pressed for its fair share of resources.

Quite early in the war the Air Staff had accepted that the Admiralty should have overall control of joint air operations connected to the Battle of the Atlantic. That meant Coastal Command was held in joint custody, with the RAF supplying men, machines and land bases while the Navy put them to work. It was a common-sense arrangement and the cogs, large and small, of the two services locked smoothly enough where they met in each of the command’s operational areas.

The friction came at the top from the endless clashes between Admiralty and Air Ministry over resources. By the summer of 1941, Coastal Command had extended the protection it could provide to transatlantic convoys but a wide gap still remained in mid-ocean that was beyond the range of aircraft operating either from Britain and Iceland on one side and Newfoundland on the other. Aggressive patrolling to locate and sink U-boats was starting to have some success, but more machines and crews were needed to change the course of the battle decisively. The Admiralty naturally made repeated requests for very long-range aircraft to expand the air umbrella and maintain pressure on the submarines.

As Commander-in-Chief of Coastal, Philip Joubert supported the Navy ‘with all my power’, only to find that his own superiors were against him.22 Requests for some of the new four-engine Halifaxes which began arriving on Bomber Command squadrons at the end of 1940 were ignored by the Air Ministry. In June 1941, a single squadron, No. 120, which was based in Iceland, was equipped with Consolidated B-24 Liberators supplied by America, which had the long legs to close the Atlantic gap. According to Joubert, Bomber Command only spared the aircraft from its ‘private war with Germany’ because ‘their engines showed too much flame from the exhausts, and thus helped the enemy night fighters’. As detection technology improved very long-range aircraft like the Liberators turned out to be very effective hunters and killers of submarines, yet in February 1943 there were still only eighteen operating in the North Atlantic.

Coastal’s bargaining power was diminished after the battle seemed to take a turn for the better in the middle of 1941. In 1942, another crisis developed. In March, more than 800,000 tons of Allied shipping was sent to the bottom, two-thirds by U-boats. There were similar losses in June and November. It seemed obvious to Joubert that some of Bomber Command’s growing resources, in particular the Stirlings, Halifaxes and Lancasters arriving on the squadrons, would have to be switched to face the desperate threat looming in the Atlantic. His representations provoked more irritation than sympathy among those who were directing the larger shape of the war.

The reluctance to divert resources takes some explaining. No one could be in any doubt about the crucial nature of the struggle and the importance of Coastal Command’s part in it. Dudley Pound, the head of the Navy, declared in March 1942: ‘If we lose the war at sea, we lose the war.’23 Churchill agreed with him, recording after it was over that ‘the Battle of the Atlantic was the dominating factor throughout the war … [everything] ultimately depended on its outcome’.

Why, then, the grudging responses, delivered with what felt like hostile relish by the likes of Arthur Harris, to Coastal Command’s modest requests for the tools to do its job? The Air Marshals gave the outward impression of treating the Navy’s needs sympathetically. Early in 1942 the First Sea Lord A. V. Alexander drew up a wish list for six and a half squadrons of Wellingtons, which were now being superseded by the ‘heavies’, to deal with increasing U-boat activity in the Atlantic. There was a further demand for two more bomber squadrons to be sent to Ceylon to help with the extension of the naval war into the Indian Ocean.

More memos fluttered across from the Admiralty carrying more requests. The response from the Air Staff seemed positive. The Secretary of State for Air, Archibald Sinclair, declared that it was the Air Ministry’s duty to ‘meet Admiralty requirements as quickly as possible’, while Portal, the CAS, assured the Defence Committee that he and his colleagues shared the sailors’ view ‘that the present situation at sea calls for substantial assistance from the Royal Air Force’.24 By this the airmen did not mean that they were in favour of any long-term transfer of resources away from the bombing campaign against Germany and towards the fight at sea. Sinclair was quick to point out that bomber squadrons would have to be re-equipped with ASV before they could carry out long-range reconnaissance duties, and by the time that happened aircraft that Coastal Command had on order would have arrived and the deficiency made good. He added that the effort would anyway be ‘largely wasted’ as enemy targets were ‘uncertain, fleeting and difficult to hit’.

The real motive behind the reluctance to give Coastal a higher priority was a determination not to allow the Air Force to be distracted from what it still passionately believed to be its true purpose: a strategic air offensive against Germany that would destroy its ability to wage war. The logic was that the Coastal Command effort was essentially defensive aimed only at preventing Britain from losing the war.25 Only offence could bring victory, and that was the job of Bomber Command. It therefore followed that Coastal should get only the minimum resources necessary to avoid defeat.

The plethora of demands came at a particularly tense time for Bomber Command. A long period of heavy losses and consistent failure had forced it into a policy of conservation while it awaited better days. It was preparing to launch a new offensive, armed with bigger and better aircraft and a potentially game-changing navigational device called ‘Gee’, which raised hopes that the squadrons might at last be able to find their targets. By now Churchill and the government were losing faith in the Air Staff’s claims for what bombing could achieve and the whole doctrine of the strategic air offensive was in danger of collapsing. Under a new commander, Arthur Harris, the bombers were being allowed another chance – quite possibly a last one – to live up to the role the airmen had claimed for themselves. Failure would mean humiliation, and the demolition of the RAF’s arguments for its own independent existence. Most importantly, it would demonstrate that what it had presented as a broad thoroughfare to victory was in fact a dead end, thereby wrecking a fundamental premise of Britain’s war planning. A breakthrough was imperative, but for the renewed campaign to have any prospect of success required the concentration of all Bomber Command’s resources.

Thus, the reasonable tone that the Air Staff adopted when confronted with calls for assistance from the Navy and appeals for largesse from Coastal Command was not entirely sincere. Their minds were set on proving the truth of the Trenchard doctrine. If that meant inflicting a degree of hardship and raising the level of risk on other fronts, then so be it. They were convinced they were at last capable of bombing Germany effectively. By devastating the cities which supplied the Kriegsmarine with the wherewithal to sustain their war at sea, they would do more to win the Battle of the Atlantic than diverting effort to a defensive maritime role in which they had little expectation of success.

No one believed this more fervently than Bomber Command’s new chief. Arthur Harris took over from Richard Peirse in February 1942. It was Peirse’s bad luck to have held the job during a depressing period of international isolation and dismal results. Harris arrived just after the planets had undergone a momentous realignment. Thanks to Barbarossa and Pearl Harbor, Britain now had mighty allies and the technical and material difficulties that had crippled the bombing effort were coming to an end.

Ruthlessness, energy, ambition and a near-fanatical faith in the power of bombing made Harris the Air Force’s most aggressive wartime leader. He had a laser intelligence and razor-edged powers of expression which he used to slash at anyone who dared to challenge his arguments and appreciations. Joubert learned straight-away that he could expect no help from Bomber Command’s stout overlord. Within a few months of arriving Harris had created a buzz of success. Raids on the strategically unimportant but highly flammable old Hanseatic cities of Lübeck and Rostock gave substance to the claim that the Air Force was causing Germany real pain. At the end of May he launched the first Thousand Bomber Raid on Cologne. These were propaganda successes rather than serious blows to the German war economy but they reinforced Harris’s faith that ‘victory, speedy and complete, awaits the side which first employs air power as it should be employed’.26 That meant throwing aircraft against German cities, not using them as a ‘subsidiary weapon’ in support of the Army and Navy.

Harris’s hectoring voice echoed through Whitehall and Downing Street where Churchill’s door seemed always open to him. In June, he called for the immediate return to Bomber Command of all the aircraft it had loaned to Coastal, for their absence from his order of battle was ‘an obstacle to victory’. A few months later Churchill supported a move to prise two bomber squadrons seconded to Atlantic duties and send them back to Harris.27 Harris also demanded the return of all bombers from the Middle East once the situation stabilized and the recall of all suitable aircraft and crews from Army Co-operation Command. According to one of the statistics, vivid but obscure of origin that he was apt to flourish, it took ‘7,000 hours of flying to destroy one submarine at sea … approximately the amount of flying necessary to destroy one third of Cologne …’

Would the Battle of the Atlantic have been won quicker if Bomber Command’s men and machines had been thrown into the fray? The question burned fiercely from the beginning, spreading well beyond expert military and political circles, and was publicly aired in the House of Commons.28 It has flared up frequently in the decades since. The debate is unresolvable. The truth is that the inter-war theories, policies and personalities of the RAF landed it in a place where there was little room for manoeuvre. Men, machines, training and doctrine all pointed in one direction, and that was to Europe and Germany. To change course so dramatically once the conflict was launched required a root-and-branch reorganization that needed to be both physical and conceptual. The timetable of war made the feat impossible. To construct an Air Force adequate to face all the challenges that Hitler threw up would have meant putting the clock back a dozen years.

To succeed, then, Coastal Command would have to adapt, to improvise, to analyse. Joubert sought solutions in science. Despite his disparaging remarks about Bowhill’s alleged hostility to boffins, he inherited from him the brilliant brain of Professor Patrick Blackett who Bowhill had appointed as his Scientific Adviser in March 1941. Blackett, who went on to win the Nobel Prize in Physics, was sceptical about the value of strategic bombing and believed that priority should be given to winning the Battle of the Atlantic. He set up an operational research unit and recruited a star team to examine all aspects of the command’s work. It was supplemented by scrupulous analysis of the pattern of U-boat activities overseen by the senior naval staff officer at Coastal, Captain Dudley Peyton-Ward, who valued every scrap of intelligence gleaned from crew reports, often debriefing the airmen in person.29 The research resulted in the issue of precise tactical drills which offered the best chance of killing submarines.

Everything hinged on spotting and surprise. To stand any chance of damaging a submarine the hunter had to catch it unawares on the surface, for the window within which an attack might succeed was tiny. It took half a minute for a U-boat to disappear into the deep, where it was all but invulnerable, no matter how many depth charges were showered on the immediate area. Even the most fractional extension of the margins increased the possibility of success. Experiments showed that camouflaging the under-surface and sides of aircraft with white paint enhanced their invisibility against the pale skies of the North Atlantic, making the German lookout’s job harder. From summer 1941, the livery of the Coastal Command aircraft operating in those latitudes earned them the nickname ‘the White Crows’.30

Tony Spooner left Northern Ireland for a hair-raising spell in Malta, before eventually joining 53 Squadron to return to U-boat hunting. He was delighted by the improvements that had taken place in his absence. The ‘greatest joy … was to be given really effective radar. No longer were we to battle with the limited ASV Mark II. Now we had a circular screen which depicted the area around as a map orientated about our aircraft …’31 He was now flying a Liberator which ‘could fly with one or possibly two engines inoperative’, fitted with anti-icing devices and a radio altimeter which reduced the old danger of flying into the sea.

U-boats tended to remain submerged during the day when within aircraft range, surfacing at night to proceed more rapidly under cover of darkness. The arrival of enhanced ASV radar gave a little more point to night-time patrolling. Even if a conning tower showed up on the screen, the target needed to be lit up for a successful attack. Bowhill had backed an initiative by Squadron Leader Humphrey de Vere Leigh, labouring in a dull personnel job at Command Headquarters, to pursue the prospect of an ASV-directed searchlight mounted in the under-turret of a Wellington. Leigh was in his mid-forties and had served as an aviator in the RNAS in the First World War. He had no technical expertise but had developed his idea after chatting with returning aircrew about their operational frustrations.32

Experiments in May 1941 were encouraging and Bowhill referred the project to the Air Ministry. The dossier landed on the desk of Joubert, then an assistant to the CAS with responsibility for radio. But Joubert was pursuing his own night-illumination project, the ‘Turbinlite’, devised by Group Captain William Helmore to guide night fighters onto bombers. The aircraft carrying the Turbinlite had to work in tandem with another which would carry out the attack. The Leigh Light seemed more promising and, after taking over at Coastal, Joubert backed it. It still took a year before five Wellingtons from 172 Squadron were fitted with the new device. By the end of the war, Leigh Light-fitted aircraft had attacked 218 U-boats by night and sunk twenty-seven of them. The beam not only made the night day but tended to blind the German gunners as the attacker moved in for the kill. ‘It was no wonder that nothing very dangerous ever came our way during this vital stage of the attack,’ wrote Spooner. ‘We were never hit once.’33

These improvements heaped yet more operational difficulties on the U-boats, forcing them to remain submerged as they made their way from the safety of their massively reinforced pens on the French coast to their hunting grounds. As was the way in the most technology dependent fronts of the war, dangerous innovation by one side stimulated counter-measures by the other. German boffins fought back with the Metox radar warning receiver necessitating a further refinement that tilted the odds back in the attackers’ favour.

There was no great clash of arms that brought a decision in the Atlantic. Instead it was a story of huge and unflagging effort, both physical and mental, that brought only incremental advantages. Eventually the cumulative pressure told and by the middle of 1943 the joint operations of the Navy and Air Force had turned the tide. The continuing threat did not allow any relaxation of effort and Coastal Command was in continuous action not only in the Atlantic but across the world in every theatre where British troops were present. By the end of the war, by their own efforts, they had sunk 169 enemy submarines and seriously damaged another 111.34

For most of the time the crews on the air and the ground carried on their duties outside the glare of the propaganda limelight which played on their fighter and bomber comrades. The names and feats of outstanding warriors like Terry Bulloch, who sighted and attacked more U-boats than any other pilot, sinking four of them, and the New Zealand ace ‘Mick’ Ensor, are little known outside the ranks of the survivors. As John Slessor, who succeeded Joubert, remarked eleven years after the war, they ‘certainly did not get their meed of public recognition at the time; nor have they since …’35