Daniel Murray

— A Collector’s Legacy

A pioneering African American bibliographer and historian, Daniel Alexander Payne Murray spent 51 years (1871–1922) working at the Library of Congress, leaving a legacy of rare and important literary materials that document the lives and accomplishments of African Americans. He believed that “the true test of the progress of a people is to be found in their literature.” An agent of change in a period when many African Americans were plagued by racial discrimination, unemployment, and poverty, he eventually bequeathed to the Library a unique collection of pamphlets and books about the contributions of African American writers and organizations working for political and social advancement. This collection, now in the Library’s Rare Book and Special Collections Division, is available online. In 1979, the Daniel A.P. Murray Association was formed at the Library to honor Murray for his exceptional service.

Daniel Murray was born in Baltimore, Maryland, on March 3, 1853, the youngest son of freed slave parents. As a young man, he moved to Washington to work for his brother who managed the Senate restaurant in the US Capitol, which was also then the site of the Library of Congress. The restaurant was located on the ground floor near the Senate committee rooms, and in due course the 19-year-old Murray came to the attention of Senator Timothy Howe of Wisconsin, a member of the Joint Library Committee, and Librarian of Congress Ainsworth Rand Spofford.

Murray impressed both Howe and Spofford, and they arranged a part-time, minor position for him in the Library. His first day of work was January 1, 1871. In the crowded Library, which stretched across the entire projection of the west side of the Capitol’s central section, he joined Spofford and a staff of eight assistant librarians, one messenger, and three laborers. The Library was open to Congress and the public daily, except Sundays, from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. At the time, only members of Congress and the Supreme Court, the president, the vice president, cabinet secretaries, and certain other privileged officials could borrow material. Books were delivered to their offices and sometimes even directly to their homes.

Murray was not the only African American on the Library’s staff. John F.N. Wilkinson, a native Washingtonian, was two decades Murray’s senior. Wilkinson began working in the Law Library in 1857, and was rewarded with the Assistant Librarian title in 1872. He served as Murray’s immediate model. The two of them made themselves proficient at what really mattered to Spofford: finding and delivering books rapidly. Urged by Spofford, whose own memory was legendary, Wilkinson and Murray each developed an infallible recall for books, titles, and locations, which made them indispensable as employees.

The 49-year-old Spofford, largely self-educated, was a bookseller, editorial writer, and abolitionist in his younger days in Cincinnati, Ohio. He also was a founder of the Cincinnati Literary Society. Enthusiasm, especially in one’s work, was the quality he valued above all others. He decided to become Murray’s mentor and made him his full-time personal assistant in 1874. He trained Murray in how to help congressmen in their research and encouraged his interest in reading, history, and the study of foreign languages. As an Assistant Librarian, Murray’s annual salary was $1,000. Murray appreciated Spofford’s patronage and friendship, describing him as “a man singularly free from the blight of color prejudice.” Spofford’s influence helped shape Murray’s lifelong interest in “putting scholarship to the service of Negro protest and advancement.”

In 1879, Daniel Murray married Anna Jane Evans, a Washington, DC, schoolteacher and graduate of Oberlin College and Howard University. During the course of their 46-year marriage, Daniel and Anna Murray raised seven children and aided each other in their careers as they became one of the wealthiest and most socially prominent African American families in Washington.

Widely recognized as an authority on African American culture and history, Daniel Murray also excelled in business as the owner and developer of several buildings in the city. In 1894, the Washington Board of Trade inducted him as its first African American member in recognition of his skillful drafting of a legislative proposal that secured federal expenditure and support for the municipal government of the District of Columbia. He and Anna also worked to advance educational opportunities for African Americans in District of Columbia public schools.

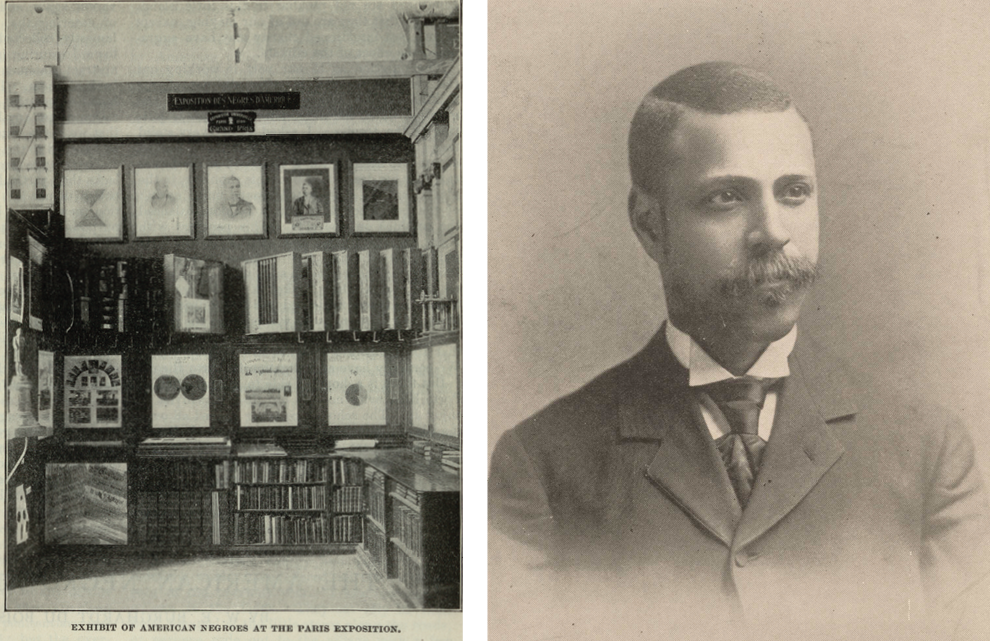

58. In 1900, the Library published the Preliminary List of Books and Pamphlets by Negro Authors for Paris Exposition and Library of Congress by staff member Daniel Murray (right). The display at the Paris exhibit (left) was considered a great success.

In the violent 1890s, African American leaders such as Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. DuBois, and Murray spearheaded projects designed to counter what they considered dangerous theories of black racial inferiority. While Booker T. Washington emphasized black advancements in the physical and social sciences and W.E.B. DuBois gained an international reputation as the intellectual leader of the African American community, Daniel Murray focused on black literary achievements.

A prolific writer and researcher, Murray authored numerous articles on black history and culture, published several reference bibliographies on black literature, and amassed thousands of biographical sketches, hundreds of books, pamphlets, and musical compositions, and even plot synopses of 500 novels, all for his planned, but never published, grand work, “Murray’s Historical and Biographical Encyclopedia of the Colored Race.” Drawing on his bibliographic efforts directed toward the Encyclopedia, in 1900—on behalf of the Library of Congress—he made a major contribution to the success of the American Negro Exhibit in the Hall of Social Economy at the Exposition Universelle held in Paris. In 1900, the Library of Congress published the eight-page Preliminary List of Books and Pamphlets by Negro Authors for Paris Exposition and Library of Congress by Daniel Murray. It was the Library’s first bibliography of African American literature.

A self-educated, self-made man, Daniel Murray pursued his work with zeal and grace, ever mindful of his mission to dispel disparaging myths about black people and to stimulate greater public awareness and appreciation of African American culture and history.

April 17 – President McKinley approves the Appropriations Act for fiscal year 1901, which includes funds to enact Librarian Putnam’s recent proposals. An increase in the annual salary of the Librarian to $6,000 also is included.

59. Large coal furnaces in the cellar kept the monumental building heated.

June – Librarian Putnam departs for a European trip to “stimulate” the Library’s exchange agreements and reorganize its overseas purchase methods.

October 19 – Putnam tells William I. Fletcher, librarian of Amherst College, Massachusetts, that after intensive study he has reached the reluctant conclusion the Library cannot use any classification system in current use—its collection is too vast and varied in its formats. Therefore, it is resuming the development of its own classification system.

October 20 – Putnam informs the chairman of the Joint Library Committee that the Library’s specialty is Americana and that it is a “bureau of information” for Americana that serves the entire nation and the world. Moreover, it will sustain active relations directly with libraries abroad and, through the Smithsonian, with all learned societies abroad.

December – A branch of the Government Printing Office is established within the Library to print and bind publications, continue the repair of historical manuscripts, and print catalog cards.

60. Philip Lee Phillips was the first superintendent of maps when the Hall of Maps and Charts was established in the new Library building in 1897. During his tenure Phillips acquired maps and atlases from the wealth of material sent to the Library for copyright deposit. He traveled abroad to add to those collections. Called the “King of Maps” by the Washington Post in 1905, he developed a classification system that became the standard for cartographic libraries and is still in use by some today.

December 4 – In his annual report, Putnam notes that the Library has expanded its foreign newspaper collection “to include those which would exhibit most accurately the current political, industrial, and commercial intelligence of the various countries in whose activities Congress and the public might be interested.”

1901

January – The Library publishes its first new classification schedule, Class E and F: American History and Geography. During the same month, it begins printing catalog cards for all books being cataloged or recataloged.

March – The Library publishes its first finding aid for a manuscript collection: A Calendar of Washington Manuscripts in the Library of Congress.

March 3 – The president approves the Appropriations Act for fiscal year 1902, which further extends access to government libraries for “scientific investigators and duly qualified individuals.” Putnam interprets the law as authority for the Library to inaugurate an interlibrary loan service.

April – The Library replaces its wagon and two horses with an electrical automobile at the cost of $2,000. Putnam points out that the automobile can be charged at the Library’s electric plant without expense.

July 4 – At the annual meeting of the American Library Association, Putnam addresses the subject “what may be done for libraries”: “If there is any way in which our National Library may ‘reach out’ from Washington, it should reach out,” he says. One proposal he discusses is centralized cataloging through the national distribution of Library of Congress printed cards.

October 15 – Putnam explains to President Theodore Roosevelt why “a national library for the United States should mean in some respects more than a national library in any other country has hitherto meant.” The Librarian points out that other American libraries must “look to the National Library” for standards and leadership in uniformity of methods, cooperation in processing, interchange of bibliographic service, and, in general, the promotion of efficiency in services.

October 28 – The Library issues a circular announcing the sale and distribution of Library of Congress printed catalog cards to more than 500 American libraries. Putnam calls the new card service “the most significant of our undertakings of this first year of the new century.”

61. Librarian Putnam called the Library’s new 1901 card service “the most significant of our undertakings of this first year of the new century.” Cards being prepared for distribution to libraries throughout the US filled this entire room.

December 2 – The Library publishes its annual report for 1901, a 380-page volume featuring a “manual” that describes its history, organization, facilities, collections, and operations. Putnam reports an increase in the Library’s total appropriation to more than $500,000 and announces that it has become the first American library to contain more than one million volumes. The purpose of the administration, he states, is “the freest possible use of the books consistent with their safety; and the widest possible use consistent with the convenience of Congress.”

December 3 – In his first State of the Union message, President Roosevelt calls the Library of Congress “the one national library of the United States” and a library that “has a unique opportunity to render to the libraries of this country—to American scholarship—service of the highest importance.”