Of Cards, Catalogs, and Computers

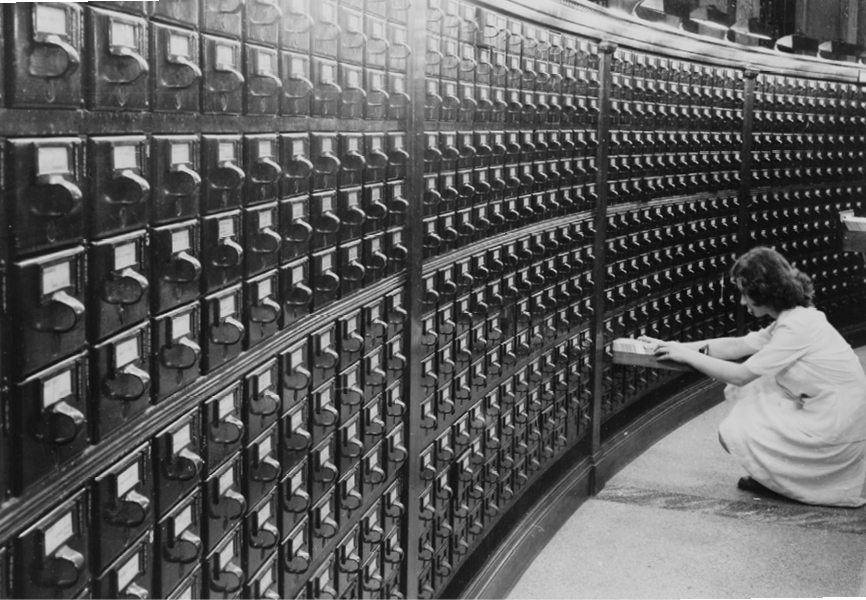

62. The Library’s public card catalog, seen in the Main Reading Room in the 1940s.

In 1877, librarian Melvil Dewey asked a hypothetical question: Could the Library of Congress catalog for the entire country? Decades later, in 1901, he received an answer. Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam, speaking from the impressive new Library building and confident about the Library’s new national mission, replied “yes.” In October of that year Putnam told President Theodore Roosevelt, “American instinct and habit revolt against multiplication of brain effort and outlay where a multiplication of results can be achieved by machinery.” The machinery in this case was authoritative Library of Congress cataloging information and the delivery means was the new technology of the day, the 3 x 5 inch catalog card.

With moral support from Dewey and Richard Rogers Bowker, editor and publisher of Library Journal, Putnam made up his mind. On October 28, 1901, he mailed a circular to more than 500 libraries announcing the sale and distribution of the Library’s printed catalog cards. Libraries immediately showed interest. A separate Card Division, under the direction of the energetic Charles H. Hastings, was established.

The Library had already started printing cards in 1898, using the recently invented linotype machine. In the fall of 1900, it established a branch of the Government Printing Office in the basement to do the printing. In 1902, Roosevelt signed a law authorizing the Library to sell such cards at a price covering their cost plus 10 percent, with all proceeds deposited in the US Treasury. And so the Library of Congress entered into the mail-order business, selling and distributing its cataloging to all who might want it. The librarian’s long-held dream of laborsaving centralized library cataloging, articulated by librarian Charles Coffin Jewett at the Smithsonian in the early 1850s, had come true. Furthermore, the Library of Congress found it had a growing national audience on its hands, especially among the more than 2,500 public libraries established by Andrew Carnegie and his foundation between 1890 and 1917.

The card distribution service became self-supporting in 1905 and soon boomed. By 1914, nearly 2,000 subscribers received cards and 41 staff members worked to fill orders. Within the Library the growth in the inventory of cards soon became a problem as tens of thousands of books were cataloged or recataloged each year. Second and third tiers were added to the steel card-storage stacks, with a fourth needed in 1921 when the stock ballooned to 63,625,000 cards. The Washington Herald for June 30, 1933, featured an article titled “Card Catalog Division of Library Recognized as Model of World.” When Charles Hastings retired in 1938, the number of subscribers stood at 6,311; the number of cards sold that year totaled 13,939,565.

The Library of Congress cataloging and classification systems were helping to shape the American library movement and having a positive influence not only on libraries but also on scholarship. In 1942, “in order to further the progress of scholarly research,” the Library and the Association of Research Libraries reached an agreement to print a complete set of the Library’s printed catalog cards in book form. In his December 1942 preface to the 167-volume A Catalog of Books Represented by Library of Congress Printed Cards, Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish lauded five “very great Americans”—Charles Coffin Jewett, Ainsworth Rand Spofford, Richard Rogers Bowker, Melvil Dewey, and Herbert Putnam—whose names, he noted, were not well known, “but have done far more for the enduring life of their country than many whose first names and photographs are familiar around every wood-burning stove in the forty-eight states.”

The Library of Congress soon began a successful program of publishing, on a regular basis, different book catalogs, which contained the newly issued catalog cards in different physical arrangements. In the meantime, in the 1950s, the Library’s own card catalog bulged with more than nine million cards crammed into more than 10,000 catalog trays. About the same time, computer companies were making major innovations and new possibilities were on the horizon for cataloging and storing data.

In January 1958, Librarian of Congress L. Quincy Mumford established a Mechanical Information Retrieval Committee to study “the problem of applying machine methods to the control of the Library’s general collections,” and the possible automation of the Library’s main catalog. Under the leadership of Henriette D. Avram, the Library devised in January 1966 the first automated cataloging system in the world, known as Machine-Readable Cataloging (MARC). Through MARC, cataloging information could be searched on a computer terminal. In March 1969, the MARC Distribution Service began sending out magnetic computer tapes containing cataloging data.

It was just in the nick of time. The number of subscribers to the overloaded but still operating Card Distribution Service peaked in 1968, when the total number of subscribers reached 25,000—and the size of the staff was nearing 600. MARC was recognized as an international standard and as its automated distribution system grew, the demand for paper catalog cards produced by the Card Division fell. In 1972, for the first time in the history of the Card Division, the dollar sales of cards dropped below the sales of cataloging in other physical forms. The end was in sight. In 1975, the Card Division was changed to the Cataloging Distribution Division, which soon became the Cataloging Distribution Service. The first computer terminals soon were installed in the Main Reading Room. On December 31, 1980, the last new cards were filed in the Main Reading Room’s card catalog and the Library launched a new catalog of its collections online.

1902

June 28 – President Roosevelt approves an act of Congress authorizing the Library to sell copies of its “card indexes” and other publications “to such institutions and individuals that may desire to buy them.” All proceeds shall be deposited in the US Treasury.

December 1 – In his annual report, Putnam announces the appointments of several subject specialists, including two new division chiefs: Oscar George Theodore Sonneck of the Music Division and Worthington Chauncey Ford of the Manuscript Division. He also reports that the Library’s Orientalia collection of more than 10,000 volumes is now “believed to be the largest representation in this country of the literature of the Far East.”

1903

January 27 – Putnam informs the Joint Library Committee that to make the Library a general circulating library for the public would “tend rather to the injury of serious research in this Library, including its use by Congress.” He points out that this function “can be more effectively dealt with by the Public Library of the District of Columbia.”

February 23 – President Roosevelt approves the Appropriations Act for fiscal year 1904. The new law authorizes US government agencies to transfer to the Library of Congress “any books, maps, or other material no longer needed for its use and in the judgment of the Librarian of Congress appropriate for the uses of the Library.”

March 9 – An executive order issued by President Roosevelt directs the transfer of the records and papers of the Continental Congress and the personal papers of George Washington, James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, James Monroe, and Benjamin Franklin from the Department of State to the Library of Congress, “to be there preserved and rendered accessible” for historical and “other legitimate” uses.

July – The Johann Georg Kohl Collection of manuscript copies of maps significant in the history of cartography is transferred from the Department of State to the Library of Congress.

1904

January 24 – A cylinder recording of the voice of Kaiser Wilhelm II is made. The recording, presented to the Library shortly thereafter, is the first phonograph record acquired by the Library of Congress.

April 20 – The Louisiana Purchase Exposition at St. Louis opens. Putnam proudly notes in his annual report that the Library of Congress exhibition, which emphasized the “National Library as a function of our Government,” was “the first direct participation of the Library in any of the great international expositions.”

December 5 – Putnam explains that his annual reports are lengthier than those of the British Museum or the Bibliothèque nationale de France only because the Library of Congress is pursuing activities “of which their operations offer no example.” One new activity is highlighted: the publication of historical texts from the Library’s collections, beginning with the Journals of the Continental Congress and the Records of the Virginia Company, which describe the settlement of Virginia.

1905

July 5 – The Librarian justifies the liberal interlibrary loan policy of the Library of Congress, explaining that if a volume be lost in the process, “I know of but one answer: that a book used, after all, is fulfilling a higher mission than a book which is merely being preserved for possible future use.”

December – The Library’s program for copying manuscripts in foreign archives that relate to American history officially begins.

63. Visitors took in the Great Hall in 1904.