The First Presidential Library

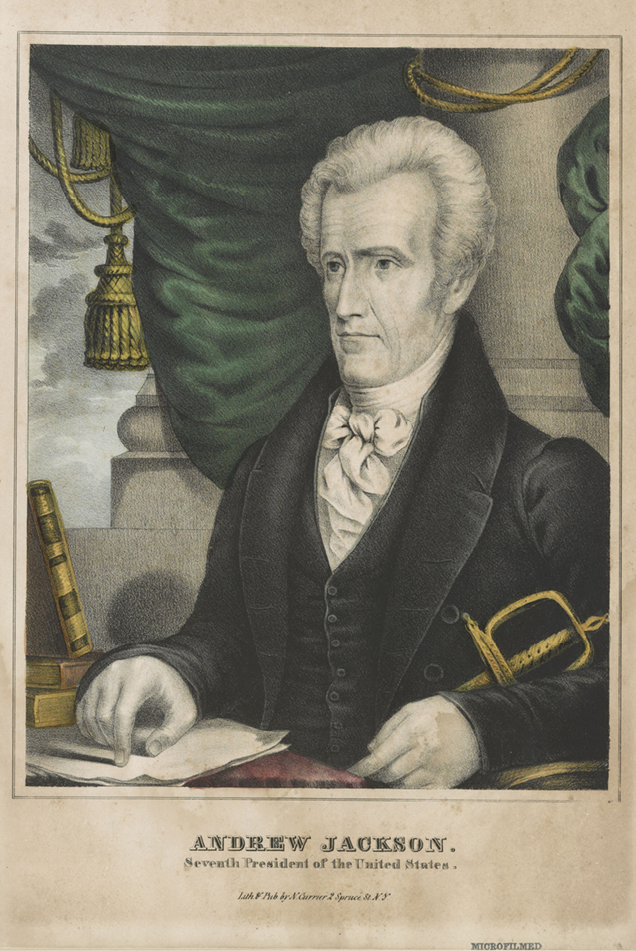

144. The papers of Andrew Jackson, 7th president of the United States, were the first presidential papers to come to the Library, in 1903. Many more would follow.

Today more than 15 Presidential Library-Museums dot the American landscape in more than a dozen states, raising awareness of the personalities and politics that have shaped American history. But few people know that the Library of Congress Manuscript Division is the nation’s oldest and most comprehensive presidential library. While recently opened and planned libraries, such as those honoring presidents Bill Clinton in Little Rock, Arkansas; George W. Bush in Dallas, Texas; and Barack Obama in Chicago, Illinois, hold papers of a single chief executive, the Manuscript Division has in its custody the papers of 23 presidents, including the men who founded the nation, wrote its fundamental documents, and led it through the great crisis of its existence. The collections range chronologically from George Washington through Calvin Coolidge and include more than two million individual items.

The Library began acquiring presidential papers soon after the Jefferson Building opened its doors in 1897. So imposing was the new structure that it seemed to be designed especially for the papers of a president. It was “the natural and fitting repository for presidential papers,” declared the descendants of American journalist and politician Francis P. Blair, who in 1903 gave the Library its first presidential collection, the Andrew Jackson Papers.

In his first State of the Union message on December 3, 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt proclaimed that the Library of Congress, as “the one national library of the United States,” had “a unique opportunity to render to the libraries of this country—to American scholarship—service of the highest importance.” Soon after the Jackson Papers arrived at the Library, Roosevelt followed those words with action. By executive order on March 9, 1903, he transferred from the State Department to the Library of Congress the papers of presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe, along with the papers of Alexander Hamilton and Benjamin Franklin.

In subsequent years, the Manuscript Division assiduously acquired other presidential papers, obtaining some by purchase—the papers of James Polk and Andrew Johnson, for example—and many others by gift—including those of Martin Van Buren, Grover Cleveland, William McKinley, Woodrow Wilson, and Calvin Coolidge.

145. The Abraham Lincoln papers were unsealed in 1947. The event was highly anticipated by scholars and the public alike. The papers were subsequently part of a popular Library exhibition.

No gift was pursued with more patience and diligence than the papers of Abraham Lincoln. Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam first approached the president’s son, Robert Todd Lincoln, about the donation of his father’s papers in 1901. Agreement was reached in 1919. However, Robert Todd Lincoln decided to seal President Lincoln’s papers, closing them to all researchers until 21 years after his own death. This delay produced rumors that the documents would reveal the complicity of members of Lincoln’s cabinet in his assassination. The papers were opened with great fanfare on July 26, 1947; the results were important for historians, but disappointed those hoping the documents contained any scandalous secrets. There were none.

The Library of Congress presidential papers collection holds items that are among the most important individual manuscript treasures in the nation. In the Washington Papers are Washington’s diaries, his commission as commander-in-chief of the American army, and his annotated copy of the United States Constitution. Jefferson’s papers contain his rough draft of the Declaration of Independence, with marginalia by Benjamin Franklin and John Adams. Madison’s papers include the incomparable notes on the Constitutional Convention, the principal source for understanding the composition and meaning of the Constitution. In Lincoln’s papers are the first draft of the Emancipation Proclamation, two drafts of the Gettysburg Address, and the holograph copies of his first and second inaugural addresses. The Woodrow Wilson Papers contain the original draft of Wilson’s Fourteen Points concerning the World War I Peace Treaty.

The size of each presidential collection varies from a handful of documents—631 in the Zachary Taylor Papers—to the voluminous—more than 675,000 items in those of William Howard Taft. On August 16, 1957, President Dwight Eisenhower approved an act of Congress authorizing the Presidential Papers Program in the Library of Congress. The Library was charged with arranging, indexing, and microfilming the papers in its possession “in order to preserve their contents against destruction by war or other calamity for the purpose of making them more readily available for study and research.” The funds were made available in 1958.

Microfilming was then the leading technology, and the Presidential Papers Program allowed the Library to successfully sell positive copies of the microfilm to libraries and scholars and to make its role as a presidential library better known. A new electronic technology was on the horizon, however. In 1990, the Library inaugurated American Memory, a pioneering effort that made digitized versions of some of its unique resources available throughout the country, particularly to teachers and their students. The Library’s microfilmed Presidential Papers collection became a key resource for American Memory, which in its early years included the papers of Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, and Thomas Jefferson. A five-year project, American Memory proved that students, researchers, and the public would use digitized primary resources if access were available. Subsequently, the list of presidential papers available online has grown to include those of James Madison, James Monroe, Martin Van Buren, John Tyler, Zachary Taylor, and William Henry Harrison. Moreover, to provide the most complete record of each presidency, the Manuscript Division continues to acquire—through gift and purchase—additional original documents and reproductions for each of its 23 presidential collections.

1986

February 10 – In extended testimony before a congressional appropriations committee, Boorstin bluntly describes the severe effects that recent budget cuts are having on the Library, calling this “a time of crisis in Congress’s Library, in the Nation’s Library.” His plea results in the restoration of a substantial portion of the recently cut appropriation.

December 10 – Boorstin announces that he will resign as Librarian of Congress on June 15, 1987.

1987

April 17 – President Ronald Reagan nominates James H. Billington, director of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and a specialist in Russian history, to be Librarian of Congress.

May – The Library receives the first installment of the Moldenhauer Archives, a collection of autograph music, manuscript, letters, and documents—and the most significant composite gift of musical documents ever received by the Library. The archive is donated through a bequest by Hans Moldenhauer.

May 6 – Librarian Boorstin accepts the invitation of the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration, issued with the approval of President Reagan, to remain in office until his successor is confirmed and ready to assume the responsibilities of Librarian of Congress.

July 14 – The Senate Committee on Rules and Administration, chaired by Wendell H. Ford, holds hearings on the nomination of James H. Billington to be Librarian of Congress. While believing that “the position as head of the world’s largest library” should be “filled from the ranks of distinguished librarians,” the American Library Association recommends in its testimony an agenda for the Library of Congress in the years ahead and expresses its desire to maintain a close working relationship with the new Librarian. Billington’s appointment is confirmed on July 24.

September 14 – In a ceremony held in the Library’s Great Hall and attended by President Ronald Reagan, James H. Billington takes the oath of office as the 13th Librarian of Congress. Senator Wendell H. Ford presides over the ceremony, and Thomas S. Foley, Majority Leader, House of Representatives, offers formal greetings. The oath of office, taken on the Library’s copy of the 1782 Aitken Bible, the first complete Bible printed in the independent United States, is administered by William H. Rehnquist, the Chief Justice of the United States. President Reagan provides remarks to which the new Librarian of Congress responds. The Library of Congress collection consists of more than 85 million items, including 14 million books, has an appropriation of more than $235 million, and a staff of 4,983 employees.

December – Billington initiates a comprehensive review and planning process to chart the Library’s future. The review includes four components: an internal staff Management and Planning Committee (MAP), an external National Advisory Committee, regional forums with local library communities, and a review by a management consulting firm. He also asks the General Accounting Office to perform an audit.

December – The Main Reading Room closes for renovation.

1988

January – Billington gives the 27-person MAP Committee a three-fold charge: to find ways to increase the Library’s effectiveness in serving the Congress, the federal government, the nation’s libraries, scholars, the entire creative community, and all citizens; to review the Library’s legislative, national, and international roles and responsibilities; and to recommend broad goals the Library should achieve by the year 2000 and practical steps to obtain them. The MAP Committee presents its vision for the Library’s future in a 300-page report dated November 1988 that contains 108 separate recommendations. During the months following, the committee’s recommendations are incorporated into a new strategic plan that goes into effect on October 1, 1989.

March – With congressional approval, Librarian Billington establishes the Library’s first Development Office.

April 13 – Billington gives the opening address for the exhibition Legacies of Genius in Philadelphia. In this talk he succinctly summarizes his hope that the Library can move simultaneously in two general directions: “in more deeply”—to strengthen the Library, its staff, and its services; and “out more broadly”—to make the Library’s riches available to even “wider circles of our multi-ethnic society.”

September 27 – To make certain the Library plays a leadership role in ensuring the survival, conservation, and public availability of the nation’s film heritage, Congress approves the National Film Preservation Act of 1988. The legislation establishes the National Film Preservation Board (NFPB) and the National Film Registry. Every year, beginning in 1989, the Librarian of Congress, with assistance from members of the NFPB and the general public will choose 25 films that are “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” for the National Film Registry, and these films are given priority in Library preservation efforts and treatment. Among the first 25 films selected are The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), Casablanca (1942), and Citizen Kane (1941). Through subsequent authorizations and expansions of the act, a National Film Foundation is created and the Library receives authority to expand is national film preservation program.

December 5 – At a White House ceremony, President Reagan signs a proclamation designating 1989 as the “Year of the Reader,” a theme promoted by the Library’s Center for the Book.

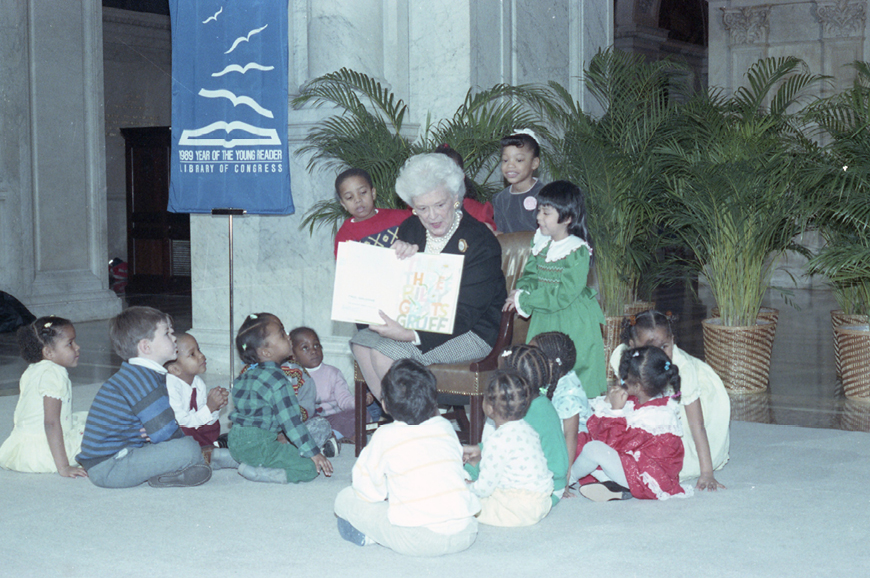

146. As honorary chair of the Library’s “Year of the Young Reader” national reading program, First Lady Barbara Bush read to young people in the Library’s Great Hall in March 1989.

1989

January 30 – In response to a request from new First Lady Barbara Bush, Librarian Billington and John Y. Cole, the director of the Center for the Book, meet with Mrs. Bush at the White House to discuss how she might help with the Center’s forthcoming “Year of the Young Reader” campaign. She agrees to become honorary chairperson and launches the campaign in March by reading aloud to a group of Washington, DC, school children in the Library’s Great Hall.

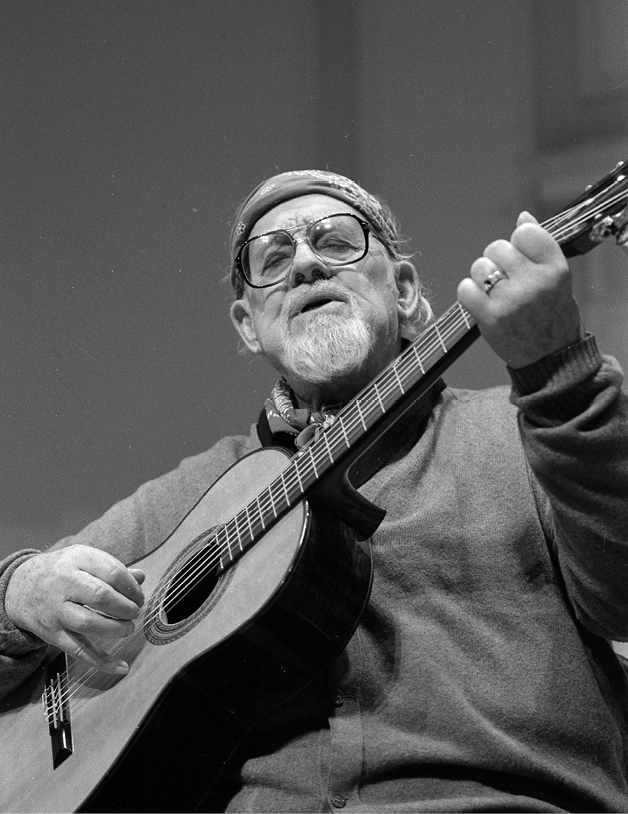

147. Folk singer Burl Ives presented a “Year of the Young Reader” concert at the Library on September 21, 1989. Afterwards he donated his guitar to the Library for its collection.

1990

January – With approval from Congress, Librarian Billington establishes the James Madison National Council, a private-sector group that will further the Library’s mission by providing financial support for digital initiatives, publications, exhibitions, acquisitions, staff development, internships, and fellowships that advance scholarship. The first official meeting takes place on January 25th.

February – The Library announces its new American Memory project, the first important step in fulfilling Librarian Billington’s goal of finding new ways of disseminating to the nation the “substantive content” of the Library’s collections. American Memory will make 15–20 American history collections available to libraries and other institutions on optical media. Drawing on the foundation of the Library’s 1982–88 Optical Disk Pilot Project, the start-up period for American Memory is planned for 1990–95, during which enhancements to the existing electronic format will be developed through prototype systems and creative repackaging. Early planning for American Memory is supported by gifts from the private sector.

July 17 – President George H.W. Bush issues a proclamation designating the 1990s as the “Decade of the Brain,” an effort “to enhance public awareness of the benefits to be derived from brain research.” The Library and the National Institute for Mental Health (NIMH) announce a joint initiative supported by the Charles A. Dana Foundation to advance the proclamation. The endeavor will include six symposia between 1991 and 1995, a 1996 celebration of the 50th anniversary of the National Mental Health Act, and a series of public and congressional programs from 1997 to 1999. In 1995, the Library and NIMH publish a book, Neuroscience, Memory, and Language, containing 11 papers from the symposia.

148. Raisa Gorbachev, wife of the president of the Soviet Union, opened an exhibit of rare Russian manuscripts at the Library on May 31, 1990.

1991

March 22 – The Library announces a new Junior Fellows program for college juniors and seniors and graduate students. This privately funded program will pay a monthly stipend for each two-to-six-month fellowship. Librarian Billington cites several fellowship objectives: making the Library’s unique collections better known, helping the Library make available previously unexplored materials, and “exposing bright young Americans to the challenging career opportunities at the Library of Congress and other research libraries.”

June 3 – The newly restored Main Reading Room in the Jefferson Building reopens, boasting bright colors and its first carpet. The card catalog has been replaced with a new central reference desk and 226 new and refurbished reading desks. The Computer Catalog Center features workstations that incorporate end panels from the original card catalogs.

149. Main Reading Room staff posed for a photograph on June 3, 1991, to mark the opening of their newly restored space, the first tangible result of a 1984 appropriation to renovate and restore the Jefferson and Adams Buildings.