I was born and brought up in several south Yorkshire mining villages. Just about everyone I knew – family, relatives, school friends, neighbours – had what might be called ‘colliery connections’. The pit not only dominated the skyline at the bottom of our street, but also impacted on lives over several generations. Mining really was a way of life for most people; and it is one of those rare occupations where stories are passed down with remarkable clarity over many years. It was not until I spent some of my time away from home, as a college student in the late 1960s, that I began to develop an interest in local history and the history of coalmining in particular. I was able to visit and interview a good number of descendants of those involved in the 1866 Oaks Colliery disaster for my dissertation. After more than a hundred years their testimony proved invaluable, unobtainable elsewhere. Since then, research, writing and teaching, the latter in both school and adult education contexts, has been a major part of my professional and recreational life for well over forty years.

It was not until the early 1980s, in the pre-internet years, that I began to explore my own family history; and now thanks to much more accessible online sources I can trace several lines of my miner-ancestors back five or six generations. But the first thing that I did – and this is standard advice for anyone beginning research – was to visit relatives so as to collect information and memories. That was the only way I could ‘get to know’ my granddad Fred Elliott, as he died when I was only two years old. Much later, my research widened to include oral history and academic projects with a large number of mineworkers. Over the years I have tried to make the results of my work accessible to a wide range of people through articles, books and deposits in museums and libraries.

Much of the the contents of this book assumes that readers have at least a basic knowledge of the main sources for family history research. But please don’t be put off if you haven’t! From time to time I have tried to incorporate general advice into more specialist investigation routes and pathways, and I’ve referred to good family history advice that can easily be obtained, ranging from fact sheets to internet guides, the latter easily available online from some excellent libraries, archive offices and family history societies.

Of course there are many general books too. Be warned though: the bibliography of the coalmining industry is a massive one. Indeed, it can be daunting for new and even experienced researchers. The standard work, Bibliography of the British Coal Industry (Oxford University Press, 1981), which is way out of date, lists 120 primary source collections, over 2,500 secondary studies and almost 3,500 parliamentary and departmental papers. Just think of the new books and papers – and internet sources – that have appeared since then. The standard academic source (but not yet digitised), is The History of the British Coal Industry, commissioned by the National Coal Board and British Coal. It is best consulted or obtained via a major library or library services as it will cost you a small fortune if you want to buy the five-volume set. Hopefully the reading/source lists that I have suggested at the end of each chapter of this book will direct you to some of the most useful sources available ‘for family historians’.

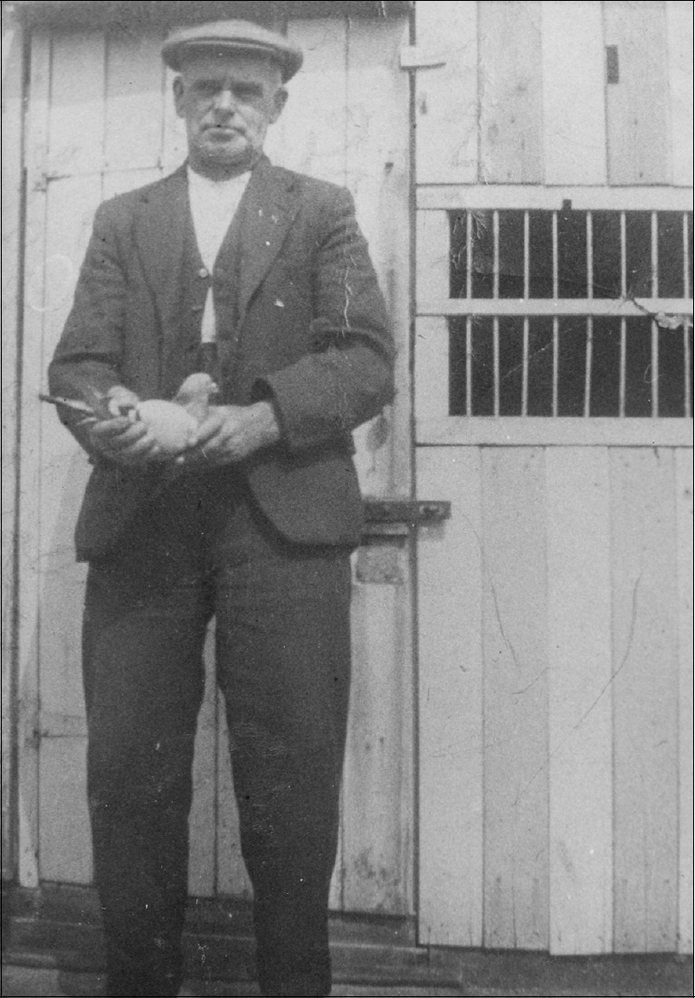

Fred Elliott (1887–1948), my paternal grandfather, at his pigeon loft in the village of Carlton, near Barnsley. Fred worked at Dodworth and Monckton collieries.

A perhaps surprising number of miners themselves have published autobiographical accounts of their life and times. Good examples of these can be extremely valuable for background information concerning one or more miner-ancestor. I have made use of several within the main chapters and certainly as part of source lists; and have made similar references to that most underrated source – oral history recordings. If I was to suggest one miner-author to read, with no hesitation I would say make use of the prolific writings of B.L. Coombes (Bertie Louis Coombes, b.1893). A miner in south Wales for forty years, his most famous book, These Poor Hands: The Autobiography of a Miner Working in South Wales, is a classic and easily obtainable. It is also well worth reading some of his less well-known writings, summarised and sampled by Bill Jones and Chris Williams (in B.L.Coombes and With Dust in His Throat) both published by University of Wales Press in 1999. Coombes’ very humane writing really does capture the life and times of a miner from the First World War through to nationalisation and beyond. He deserves to be read by anyone with mining ancestry.

Unfortunately, coalminers are often portrayed in stereotypical extremis, banded together as militant agitators or habitual drunkards, even as a ‘special breed’. In his ‘urban rides’ to Wigan and Barnsley, Orwell portrayed them in situations meant to shock 1930s society, echoing the work of the nineteenth-century commissioners. Other authors present the miners as archetypical proletariat workers. In reality – and this is where good family history research is so important – miners lived in communities where the pit, family, sport and leisure, politics and even religion combined and interacted in many positive ways; and especially manifested in deep friendships and an unspoken camaraderie engendered by the ever-present shared dangers of the job. If you get the chance do go and see Lee Hall’s Pitmen Painters play, based on the painter-miners of Ashington, or, for life at a colliery, get hold of a copy of The Price of Coal (1979) by Barry Hines.

Although employment numbers were huge, coalmining family histories are not easy to research. Pits were usually short-lasting enterprises, relatively few surviving a hundred or more years in a single ownership. That’s why miners were so mobile and not easy to track, even on the censuses. They might lodge somewhere for a short time and then move on. The coal owners and coal companies were not always the best of record-keepers anyway. Even when they were, their papers may not have survived or have been deposited in archives. What remains is well scattered among regional and national repositories. The Big Question that everyone asks relates to personnel records. If you are researching a direct and recent miner-ancestor then you may be able to find some or part of his employment records via application to the Iron Mountain repository, but otherwise finding personal information, if any, is difficult. However, there are still some very useful pre-1947 company and colliery records in regional and national archives. These can be used alongside general sources such as Ordnance Survey maps, local newspapers, estate and tithe maps and trade directories, and of course standard family history sources such as census, civil registration and parish registers.

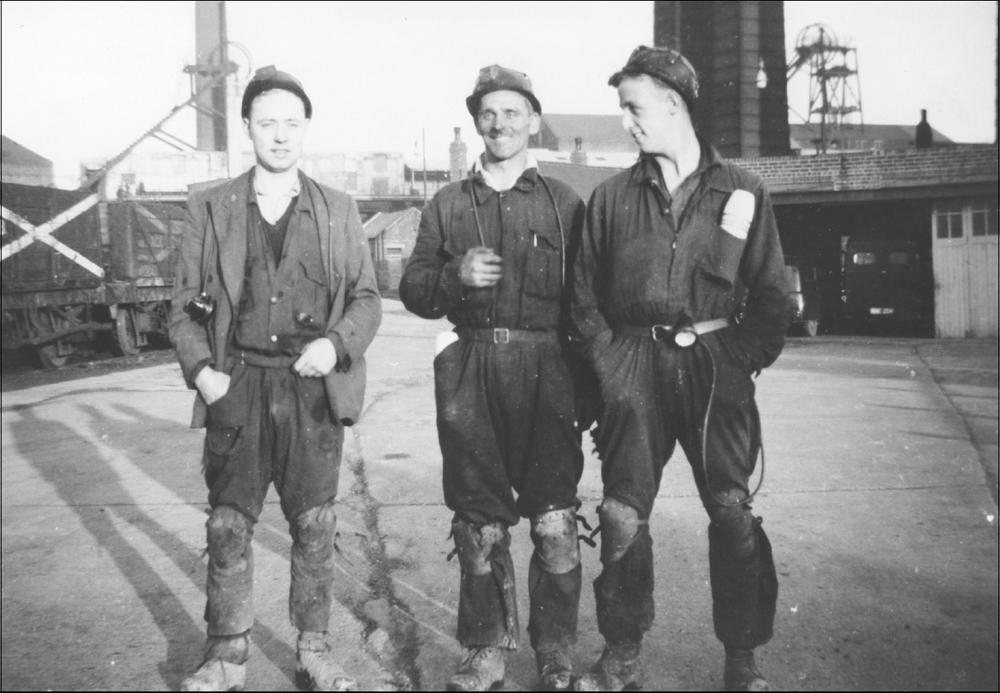

This is the only photograph I have of my father, Fred Elliott (1917–2007: centre of image) in his mining clothes, pictured at Wharncliffe Woodmoor 1, 2 & 3 Colliery in the mid-1960s shortly before the pit closed. He had worked there since the age of 14 and later found a similar job, but on the pit top, at nearby Grimethorpe Colliery.

There are remarkably few modern guides to researching coalmining ancestors: David Tonks’ My Ancestor was a Coalminer, published by the Society of Genealogists, is a worthy exception. Also still useful is Alison Henesey’s Routes to Your Roots. Mapping Your Mining Past (National Coal Mining Museum for England).

What I have tried to do in this book is run contextual information alongside research advice in the main chapters of Part One. I have also included several themes that have had relatively little coverage elsewhere from an ancestry viewpoint, for example ‘miners at war’, ‘researching ancestry through objects and ephemera’ and aspects of ‘accidents and disease’. Part Two, the main reference section, relates to regional and national sources. When researching and writing this section it became clear that a good number of libraries, archives and museums were being revamped and/or rehoused. I have tried to be as up-to-date as possible but do check websites and social media sites for the latest news.

If you can place your miner-ancestor in a meaningful historical and social context it will have been a very worthwhile piece of research, not just for your family, but also for future generations – and for mining history as a whole. It really is worth all the effort: the subjects themselves deserve it. And finally, whilst the internet and commercial sites are wonderfully convenient tools for researchers, do make use of libraries, archives, museums and family history societies in person, where expert support and help is always available.

This c.1891 studio photograph shows my great-grandfather Jonas Elliott (1845–1892) with his wife Harriet and surviving members of the family (two children died young). They lived at Deepcar, near Sheffield, where Jonas worked in small coal and ganister mines. The constant inhalation of silica and coal dust in dreadfully cramped workings led to many premature deaths due to respiratory diseases in this area. Jonas looks far older than his 46 years and probably realized that he was dying when he took the family to a local photographer’s studio. He passed away a few months later, and was buried in an unmarked grave in Bolsterstone churchyard. His eldest son George (standing) died aged 30 from the same ‘complaint’. My grandfather, Fred Elliott, is the small boy sat on Jonas’ knee: another boy miner in waiting.

Brodsworth Main Colliery in the Doncaster area was sunk to the famous Barnsley coal seam from 1905 to 1907 and the model village of Woodlands soon developed, providing comfortable houses for hundreds of miners and their families. During the 1920s the pit became one of the largest and most productive mines in Britain, employing well over 4,000 men and boys and even providing coal for the fires of Buckingham Palace.