DISCOVERING THE WORKING LIFE OF YOUR MINER-ANCESTOR

Mining is one of the few occupations where working memories are passed down over several generations. Workplace camaraderie, close-knit families and living in distinctive communities have contributed to what might be called an inherited testimony; as has the very nature of the job. Even putting the very worst aspects of mining on one side: accidents, disasters and, the most underrated of all – industrial disease – your miner-ancestor worked in one of the dirtiest and most demanding of all British industries.

For most families in mining areas life revolved around the pit: it was the norm, it was what was required and there was little or no alternative. Dad went down the pit and so did his son or sons. Brothers and uncles did the same, as did most of neighbouring bread-winners. It would be rare if your miner did not have a family member or relative or friend or neighbour who also worked at the same or a nearby colliery. That is why the neighbourhood and community should be an integral, rather than occasional or incidental, part of your research.

Working in shifts underground for seven, eight or more hours a day, for five to six days a week, required considerable fitness as well as mental fortitude. But that was not the end of the story. The miner still had to get to work and go through a set preparatory routine before descending the shaft or drift; and may have had to travel underground, one, two or more miles to the place where the job actually started; and the point where he really got paid. Of course, the same routine was repeated in reverse order at the end of the shift – with the addition of getting washed at home (or in the pithead baths in later years); so in reality an average workday could easily be extended by at the very least a couple of hours. Not surprisingly, young and old miners (and a good number of middle-aged ones too) fell asleep in their pit muck, absolutely exhausted, well before starting their main home meal, or went straight to bed after returning from the night shift. And yet some men worked, albeit often on so-called ‘lighter’ jobs, well into old age; others, like my paternal grandfather, a former ‘trammer’ and proud collier, suffering from illness and disability, worked in the pit top winding engine room, on maintenance work, keeping the place clean and tidy. He had no retirement though, passing away at the age of 60.

Almost naked and covered from head to boots in muck and grime, two haulage hands pause by their tub of coal, c.1915. Another black-faced lad, still with his shirt on, can be seen in the background. Once ‘clipped on’, an engine-powered ‘endless haulage rope’ dragged the tubs to a much cooler area: the pit bottom.

Much of this chapter is based on interviews conducted with former miners born well before the nationalisation of the mines in 1947. Although mainly from Yorkshire, their experiences are fairly typical of other regions. The older men, speaking in their 80s and 90s (and a few at the great age of 100 or more) refer to jobs and conditions that existed generations earlier. This oral testimony may therefore help us appreciate what work was like for a miner and his family during the nineteenth as well as the twentieth century.

Boy miners

The 1842 Mines Act prohibited the employment of boys under the age of 10 years working underground, as from 1 March 1943. However, the Act did not have full compliance in its first few years of operation, so don’t be surprised if you find that your 8 or 9-year-old ancestor is listed as a miner in the 1851 census return. It was not until 1887 that the legal limit for working underground was raised to 12 years.

Boys were not allowed (or supposed) to work underground until they had reached the age of 13, as from 30 July 1900. The 1911 Coal Mines Act (effective from 1 July 1912) prohibited any boy under the age of 14 working underground, though of course they could be employed on the pit top, and very many were. After the First World War and the Fisher Act of 1918 the age of compulsory education was in any case extended to the age of 14. However, some youngsters were still allowed to leave when 13, something that one of my ancestors achieved – by ‘getting his papers signed’ (obtaining a certified basic standard of education). Thus some some 13-year-old boys (and very briefly [from January-August 1900] some aged only 12 years) did work at collieries before and just after the First World War, but not, again supposedly, underground.

The 1911 Act also restricted the employment hours of boys to 54 hours a week, and they were not allowed underground after the hours of nine at night and five the following morning. Sundays and Saturday afternoons were excluded for ‘boy labour’.

The Butler Education Act of 1944 raised the school leaving age to 15, a figure that remained in force until 1972, when it was extended to 16 years.

It was not unusual, before the introduction of the state pension, compulsory retirement age and nationalisation of the coal industry in 1947, for miners to continue to work well into their late 60s. Occasionally, even with disabilities, some veterans continued to work in their 70s, even 80s. There are many examples in nineteenth-century census returns of old miners. This was because, apart from minimal Poor Law relief, trade union and family support, there was little alternative other than to work. It was not until 1908, thanks to Lloyd George, that the first state pension – 5s (25p) a week for men who were aged 70 – was introduced; but it was means tested. In 1925, the pension, now for 65-year-olds, was based on contributions from the employer and employee. Established in 1952, the Miners’ Pension Scheme (MPS) continues to provides small pensions to former mineworkers. Originally contributions were voluntary, but became compulsory from 1961. The MPS closed for contributions after the privatisation of the coal industry in 1994.

Tip

Talk to old miners and don’t miss an opportunity if you have one to record the memories of any surviving mining relatives. Most of them will love to recall their experiences, good and bad. Keep the session fairly brief and visit them again after you have listened and transcribed the information. Don’t barrage interviewees with loads of written questions; it’s far betterto stickto broad themes and events and keep the interchange informal. Even where some facts are wrong and/or exaggerated, listening to mining terms and recording the person’s voice is well worth the effort. Failing that, do make use of the many thousands of oral history recordings available online or at national and local museums, archive offices and libraries (see the regional and national reference sections of this book). Although the recordings are from non-related individuals they will help place your ancestor in far better context than otherwise.

Getting set on

For many years, leaving school and getting a job at a pit was an informal and fast process. After a few ‘weighing up’ questions it was just a case of the manager or his representative setting a starting day and time. Having a father or relative already working at the pit was a great advantage. Even religion might play a part. Many youngsters left school on the Friday afternoon and were working at the pit early on the Monday morning, some dispatched underground. Later, from the 1930s onwards and certainly after nationalisation (post-1947), matters were more formal, with youngsters being seen by ‘training officers’ at the colliery, and of course there were close career links with local schools and youth employment services.

New Starters

Tom Emms (b.1911): The pit was the only job to go to. I was 14 on the Thursday and on the Saturday morning my father took me to the colliery [Edlington Main] to see the clerks and the under-manager and I signed on. On the following Monday I was at the pit at 5.30 in the morning.

Johnny Williamson (b.1912): As soon as I was 14 I was told ‘You had better get down the pit lad, they are setting men on’. I went there on my own and knocked on the manager’s door. I was asked my particulars and who my father was. As soon as I told them that my father and grandfather were miners I was accepted and I was signed on as a ‘nipper’ [pit boy].

Roy Kilner (b.1923): The last week in December me and a friend went to Barnburgh pit to get a job. We went into the under-manager’s office and enquired, ‘Any vacancies, Sir?’ He asked me if any of my family worked there. I said, ‘Yes, my Uncle Ted.’ ‘Oh,’ he replied, ‘he’s a good worker. You can start on Monday.’

Arthur Nixon (b.1931): I went on my bike to North Gawber pit one foggy day and was directed the manager’s office, reached by some steps alongside some other offices. I knocked on the door and a voice called out ‘Come in’. There were six chaps inside, in their pit muck, sat around a roaring fire. ‘Now then lad, what can I do for you?’ the manager said. I told him I was looking for a job. ‘What sort of job?’ he replied. I asked if there was a job in the electric shop. He looked at me and asked, ‘Are you religious?’ I said, ‘Well, I went to Sunday school but that’s all.’ He told me that there were lots of ‘bible-punchers’ there but gave me a note and sent me to speak to Fred Moxon, the engineer. He asked me a few questions and asked me when I could start. I started the next day.

Most mines worked a 24-hour day, so having labour close at hand was an essential requirement of estate owners and companies before major transport systems were fully developed. Rows of artisan cottages were built during the eighteenth century by great landowners such as Earl Fitzwilliam, at Elsecar, not far from his great house at Wentworth, near Rotherham, close to his colliery.

Throughout much of the nineteenth century many hundreds of small rural communities in mining areas were transformed into ‘pit villages’. Carlton, the south Yorkshire village near Barnsley where I was brought up, was largely changed due to opportunistic private landlords, but a new coal company community consisting almost entirely of miners’ families were housed in Carlton Terrace (or ‘Long Row’ as it was commonly called), right next to the mine. The top end had a working men’s club but the bottom, right by the canal and pit, had an adjacent shorter row of superior quality houses where the officials and policeman lived. The manager lived in a small but imposing mansion in the old village.

Getting to the pit

John Williamson (b.1912): Gran would wake me up with a shout, usually several shouts, each getting louder, at 4am. My snap would be waiting for me, wrapped in the Daily Herald, which was the working man’s paper. I would meet my mates at the end of the street and we would walk a mile and a half to the pit.

Bernard Goddard (b. 1917): I pedalled there on a second-hand bike, which cost me me £5 at 2s 6d a week.

George Kemp (b.1920): It was 4am when I got up. I had to walk from Winn Street into Barnsley and then caught a bus to Carlton, but sometimes would walk it to save money.

Roy Kilner (b.1923): Me and my brother walked to the pit. I was still dressed like a school kid, in short trousers. I walked two and a half miles. As we were going home I made up this little song:

With my snap tin on my belt

And my Dudley on my bike,

I’ll be off to Barnburgh Main in the morning!

With my hard hat on my head And my pit boots on my feet,

We’ll be off to Barnburgh Main in the morning!

New off-shoots to old villages emerged, a mix of private and planned initiatives. Close to where I now live, in the Doncaster area, the pit village of New Edlington developed rapidly following the sinking of Edlington Colliery (later known as Yorkshire Main) in 1909/10, very different to the original Norman settlement, which became known as Old Edlington. In the space of twenty years the population of the new village exploded from about 580 in 1911 to over 5,000 in 1921.

Architect-designed model housing estates were created by the more enlightened companies nearby. Percy Bond Houfton, for example, designed ‘Woodlands’ for the Derbyshire-based Staveley Coal and Iron Company, serving what became the biggest pit in the country, Brodsworth Main, just before the First World War. Woodlands was laid out on garden-city lines and houses were ‘individualised’ via the fashionable Arts and Crafts style. The model village tradition continued well into the twentieth century when technology enabled large new deep collieries to be sunk through previously inaccessible land. After nationalisation, the NCB inherited and further developed its own huge housing stock, becoming one of the largest landlords in the UK.

Despite the close proximity of pit houses, many miners walked to their pit from surrounding villages and towns, such was the great demand for labour and the pull of work. Perhaps exceptionally, one miner that I interviewed, Stanley Potter, worked at fourteen different pits in search of better pay and conditions prior to leaving home to get married, then settling down to work at a colliery where he remained until retirement. Every day Stan walked about six miles to a remote drift mine, attracted by slightly better pay than at his local pits. For most, however, getting to work was a communal rather than solitary journey, the miner meeting an increasing number of mates on the way. Towards the end of the century many miners used cycles to get to work and the rail and new tram networks greatly enhanced mobility. During the first few decades of the twentieth century a profusion of private omnibus companies provided special ‘pit bus’ services to collieries, further increasing access.

First days: working at the pit top

Many former miners will remember their first day at work, some recalling the occasion as a mix of fear and trepidation, others in a more relaxed and matter-of-fact way. The first few weeks and months might be spent on the pit top, say helping out in the timber yard, or doing a job such as working on the screens (where coal was sorted), alongside other boys and a few old miners who through age or disability were unfit to work underground. Ironically a good deal of the work was as dirty and noisy as working underground.

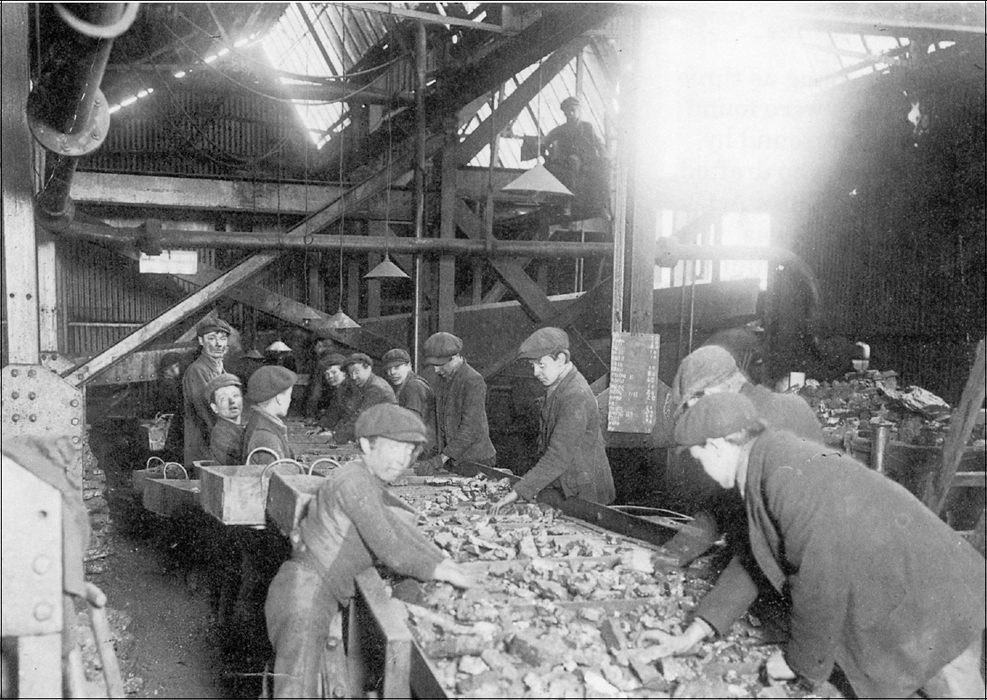

Boys sorting dirt from the coal on the picking belts/screens at a colliery near Bargoed, south Wales, in 1910. Note the elevated position of the man in charge, and the chalked tally list. (NUM)

Screen boys

John Bailey (b.1900): It was a rotten job. A chap from Darfield was the ‘bummer’. He went to chapel but he was a lousy boss. We could never do anything right for him. He shouted at us but did not swear, forcing us to do things, for instance, if some of the belts halted he would find something for us to do while it was being repaired.

Arthur Clayton (b. 1901): I then got into this place and it wanted John Milton to describe it because it was Miltonic! It was dim and dusty and noisy and there was a little man in charge of us. He had been a teacher but had lost his job, through drink. There was a big belt, really iron plates, which went round an hexagonal thing … there were some big mechanical riddles … bump, bump, bump … you could not see for dust. As it [coal and debris] came on the belt a boy stood at the bottom of a big riddle. He had a big rake and would spread it along the belt and there were boys on either side, picking out dirt and throwing it over their shoulders to a place at the back which had a trap door leading to the wagons … A little Irishman was in charge. When you were day-dreaming and not picking dirt out he would shout ‘I will cut your liver out and put it back and swear I never touched you.’ Later we used to laugh about it when some of us had retired.

George Rawson (b.1913): My job was to pick dirt out of the coal on the screens. I wore shorts and old clothes. The screens were large iron conveyors on which coal came out of the pit. It was tipped down chutes by tipplers. As the coal passed us boys we had to pick the dirt or muck out on to this big conveyor belt. At that time the cleaner the coal was then the more money the owners got.

First days: working underground

Many other young miners worked underground on their first day. Travelling down in the cage at great speed was an unforgettable early experience. Jobs below often involved basic haulage work (loading/unloading tubs in the pit bottom) or general duties. For some, their work was not that far removed from early Victorian child mining: as ‘trappers’, opening and closing air doors; and later as ‘trammers’ (also known as putters, hurriers and drawers), pulling and pushing tubs along rails.

A flat cap, old flannel shirt, waistcoat and moleskin trousers (or ‘bannikers’ – knee-length britches) and boots or clogs were the usual clothes worn by miners right up to the 1940s; and a good deal of the clothing might be reduced to shorts or pants in hot working conditions. Some miners would tie string to their trousers just below the knee, in order to keep the bottoms from getting wet and combat invasions of vermin. Infestations of insects, mice and rats were not unusual, accidentally introduced into the mine with bales of straw and horse feed. There were no toilets or washing facilities underground, and lunch or snap time was usually limited to a ten or twenty-minute break taken wherever work took place. Not surprisingly, in view of the working conditions, plus accidents and disasters, life expectancy for miners remained well below the national average throughout much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Pit bottom boys, lamp carriers, door trappers and trammers

Jack Steer (b.1898): When I got to the pit bottom my brother told me to sit there for a while while he reported to the deputy who took me to a corporal, the man that dished the jobs out, and he set me clip-carrying. These clips were put on the ropes and pulled the tubs to the districts and back again. I was dragging clips and chains from one end of the shaft to the other. It was very cold by No. 1 shaft but No. 2 shaft it was nice and warm, warm air coming from the districts.

John Clamp (b.1900): I wore shorts and had clogs on my feet. I was on nights on my first day working as a ‘deputy’s boy’ and had to walk with him, but he sat me down and left me in the dark! I went to sleep until he came back.

Arthur Clayton (b.1901): My first job underground was lamp-carrying, getting four safety lamps from the lamp room and taking them down the pit, walking a long way with a lot of other boys and men. During the shift, if some colliers ‘lost’ their lamp I had to swap them. They frequently went out, just a jerk would do it. Then I had to walk back to the pit bottom.

Johnny Williamson (b.1912): I was given a CEAG electric hand lamp, which had recently been developed but it weighed 71bs. I was only 4 foot 6 inches so the lamp dangled from my leather belt, knocking my knees. I soon got used to it. I wore clogs on my feet. When we went to work they would say ‘Clogs are going!’ Going down the shaft was a bit strange at first. I was told to stand in the middle, there were fourteen of us on one level of a 3-decked cage. We used to go down in 45 seconds, slowly to start off, then there was a ‘whoosh’ and we were down. From the pit bottom I walked about a quarter of a mile and tripped over just about everything I came across.

Ernest Kaye (b.1917): I was absolutely terrified that first morning, going down in the chair. My old lamp was on my belt and I held on to the safety bar, got off at the bottom, feeling frightened to death. I was told to stay with this man on an 8-hour shift. When I got home Mother asked me how I had got on and I said ‘Shocking!’ I was a door trapper. There were big wooden doors, two together, since when you opened one to go through you had to shut that one and open the other so the air was not stopped. I was shown what to do, allowing people to pass through, opening and shutting. The air pressure meant pulling the doors hard, using the bar on them, and going through with whoever was passing. I sat on a bit of wood or stood, waiting.

Stan Potter (b.1922): I soon found out what tramming was really like. First he (the collier) told me to get some clay out of the bankside near the pit (a drift mine) entrance and to keep it working with my hands, like plasticine, spitting on it and getting it going. Then he said, ‘Here’s your candle, lad.’ The colliers had to buy their own candles. We went down and into the pass-by and he uncoupled a tub and started tramming it, to show me what to do. The candle was stuck in the clay and placed on the tub. On the main level, about 5ft high, it was okay, but when it came to going along the low gate it was only a yard high and fairly steep. He pushed it up okay and and told me how to drop it off at the end of the rails, leaving a little gap to throw coal into the tub. When the tub was filled he just put a locker in the back wheel, lifted it on the rail and pushed and it slid along. It looked easy. Well it did not work for me. I could not push the tub like he did. I tried using my head against it as I had not enough strength in my arms and had not got his balance or his technique; and had not got his knack of going over the sleepers. My clogs hit them and my back kept hitting the roof. When I got to the end of the gate my back was streaming with blood, all along the vertebrae. I wore a pair of clogs, a pair of tramming drawers [long pants] and was stripped to the waist; and a cloth cap. Later I was in the kitchen getting washed and my mother came to wash my back and noticed all the tom flesh. She said, ‘Oh Stanley, what a mess. You can’t go there again’. I did. I got used to it and kept my back lower, tramming like my dad did.

James Reeve (b.1928): Dad took me to the box hole [hut-like underground office] and left me with the pit bottom deputy who gave me a sweeping brush! I had to sweep the box hole out and then nearby roadways. It was done to get me used to the pit bottom and get my underground eyesight. The first day seemed an eternity.

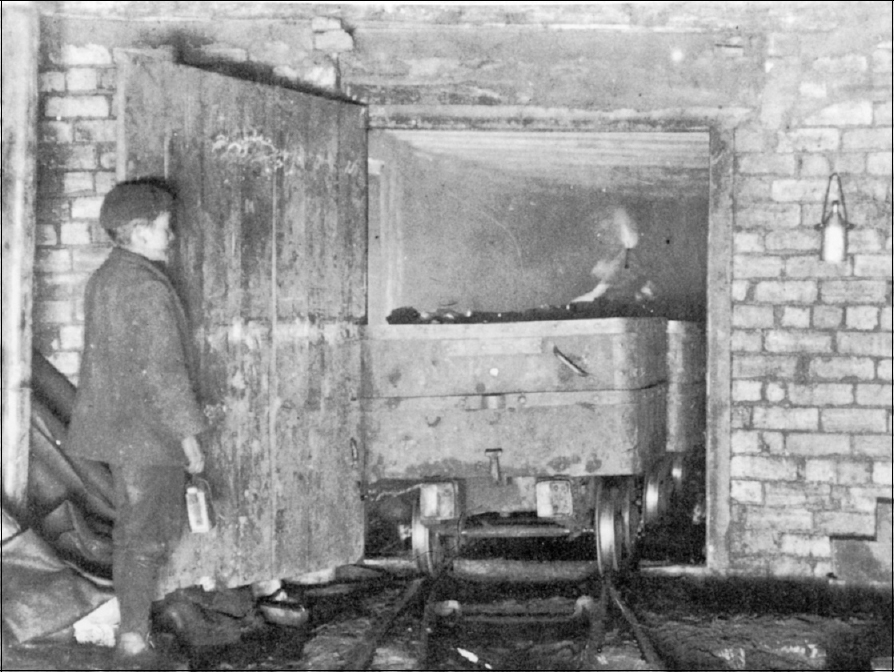

One of the loneliest jobs in the mine: a boy door trapper had to open and close a ventilation door – on demand – to allow tubs to pass through.

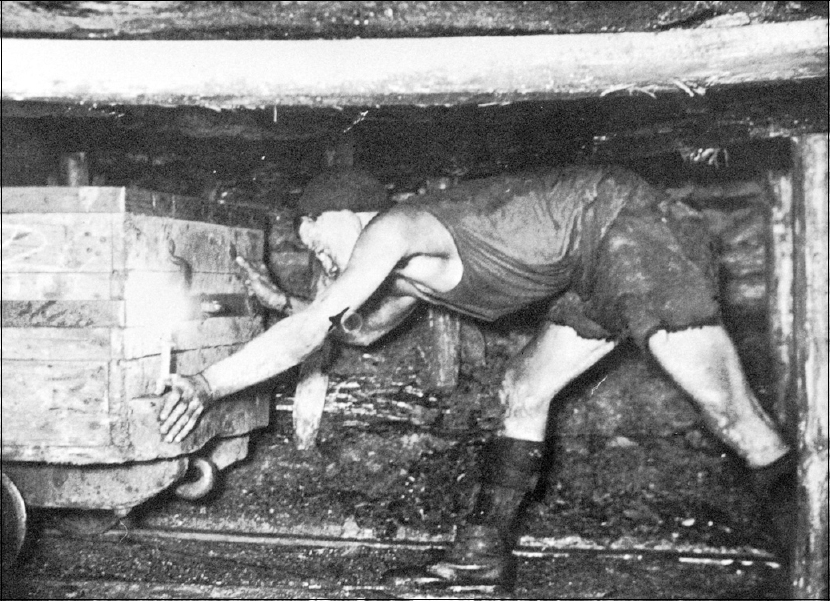

‘Tramming’ – pushing tubs of coal on rails – was an arduous job, especially along low roadways with only a candle for light.

Pony drivers

Young miners, from about the age of 12, were often described as ‘pony drivers’ in census returns and other documentation. Training was minimal and some miners will tell you that the ponies and horses were looked after far better than themselves. From the late 1870s there were strict rules and regulations so as to ensure that the animals were worked properly and not abused, reinforced further via the 1911 Coal Mines Act and subsequent amendments.

Responsible to the ostler or stableman, drivers were in charge of the working animal, when hauling tubs (or trams/hutches as they were also known) to and from the coal faces. It might be a single tub or two, or a train of linked tubs. The horses, despite the complicated logistics of getting them up and down the shafts, were given an annual break during the miners’ paid feast or holiday week, after 1938. Occasionally, during the longer strikes they were also given a respite, even taking part in events such as agricultural shows and even races.

‘Pit ponies’, really horses of various breeds, were an essential though often controversial part of underground mining from as early as the mideighteenth century in the North East to well within living memory. In 1878 there were over 200,000 horses at work in British mines, according to the RSPCA. Numbers decreased to around 70,000 by 1912. Founded in 1927, the Pit Pony Protection Society was totally against the use of the animals for mine haulage work. Nevertheless, and despite mechanisation, horses remained useful in some mining situations, over 21,000 still at work in 1945. Numbers rapidly dwindled to 632 by 1971, mostly concentrated in Northumberland and Durham.

A young pony driver, water bottle in his pocket, collecting his horse from the stables. The animal also has some protection: a leather cap, with dual projections that served as blinkers, c.1940s.

Colliery horses featured in a 1976 Walt Disney film, Escape from the Dark (or The Little Horse Thieves [USA title]), about an attempted rescue of ‘condemned to be killed’ horses following the introduction of machinery at a Yorkshire mine. Robbie and Gremlin were probably the last colliery horses in Britain, retired from a small south Wales drift mine in 1999. Robbie continued demonstrating his skills, albeit to surface visitors, when pulling small tubs around the site of the National Mining Museum for England (NCM), for a few years afterwards. Patch, another veteran Welsh horse, was the last of the NCM’s working horses, passing away in 2011.

Tip

For background reading about horses and ponies in mines see Ceri Thompson, Harnessed. Colliery horses in Wales (National Museum of Wales, 2008); Derek Hollows, Voices in the Dark. Pit pony talk and mining tales (lulu.com, 2011); also useful are John Bright, Pit Ponies (Batsford, 1986) and Eric Squires, Pit Pony Heroes (David and Charles, 1974).

Arthur Clayton (b.1901): All the new lads had Dan because he ruled II. himself. He was a small pony and would do anything. There were some bad ones. One was called Snap! It used to stand and kick, breaking all the gears. On rare occasions two or three boys were killed when the pin jerked out and they fell and the truck ran over them. You used to sit behind the pony, like a drayman … taking three empties at a time and bringing three full trucks back.

The head stableman for the whole pit used to come and kill badly injured ponies with a ‘peggy’. While it was on the floor they would hold two or three safety lamps before its eyes and then would suddenly remove them and let bang.

Tommy Hart (b.1905): There were about thirty-six ponies. Some were named after First World War battles such as Verdun. Ponies were well looked after. They would walk on their own to the stables and go in their own stalls. It was unbelievable, you did not have to guide them. Sometimes they could be awkward but I never got kicked. I remember that we rode them (against regulation). I got on top of the pony and laid down so my head was below the pony’s head but we did not do it a lot. The stablemen were very strict and would inspect every horse and pony and you got a clip around the ear if there was something wrong.

George Rawson (b.1913): Father came home from the pit one day and told me he had got me a job working with him as a pony driver. I was 14 and 3 months. I had to report to the box hole [‘office’] in the pit bottom and the deputy would tell me where to go. I walked to the stables where Mr Silcock was in charge. He was very keen and really did look after the horses. When you got back at the end of the shift he would examine them to make sure that there were no cuts, bumps or bruises. We put the collar on and the harness or gears, which were hung in the pass-by. The chain, which was about 5ft or 6ft long, was hooked on to the tubs. The miners would fill the tubs by hand and take them to the pass-by. My pony was called Midget, the smallest in the pit, but I was only small myself, 5ft 2 in. It was well behaved and intelligent but it would not stand still while I put his gears on at the start of the shift. Sometimes the ponies would catch their backs on the roof so the deputy would send the repair men to dint [lower] the roadway. Later I had a pony called George, the same name as me! If we rode the ponies we got into trouble. Every so far down the roadways there were man-holes where you could go for safety. The stableman might hide in there, with a brush and bucket of whitewash, so that when the drivers rode past they they were splashed, so there was no excuse when you got to the pit bottom. We then got a telling off but if you did it too often you got some money stopped from your wage – and that meant trouble at home as well!

Norman Rennison (b. 1922): At South Kirkby they were more like cart horses compared to ours, which were more like New Forest ponies. I drove one which was called Gypsy. It had its tail trimmed, a lovely little pony but it got killed, though not through me. The bloke was taking him out, through the doors, but he should have made sure that nothing was coming and it was hit by some tubs and put down. They used a spiked cap for this, the shape of the horse’s head, with a hole in the middle and a spike went into the hole and was banged with a hammer. We used to have to fetch dead ponies off the units on trams which were like tubs with no sides.

You must not hang your coat up with an apple in your pocket anywhere near a horse or he would eat it.

At holiday times we took the ponies out of the pit and into the fields. A box with wooden sides was used to contain them on the chair and it was wound up slowly but they sometimes slipped on metal plates. The ponies got to know you. Some were Welsh mountain ponies and a few were Shetlands. One was called Dot, a great little worker. Another was called Pride, a grey, who used to bang his collar at the back of the tubs and would shove them with his collar, nearly a hundred tubs at a time but they were small, not like the big modern tubs. There were mice in the stables but we had a couple of cats and they got bottles of milk everyday.

Job variety and progression

Some miners were quite happy to work on a variety of jobs during their pit life. Day-labourers – ‘datallers’ as they were sometimes known – were paid a daily rate for miscellaneous tasks. Many others preferred to progress to ‘learning a trade’ or specialising and there were plenty of opportunities to do so: as electricians, surveyors, fitters (repair and maintenance workers), engine drivers, plumbers, joiners, blacksmiths, bricklayers, and so on. A National Schedule of occupations and and job descriptions drawn up by the NCB identified 194 underground jobs, 221 surface jobs and 120 jobs in central workshops; and there were many locally-named variations of each one.

For many young miners, progressing to work at the coalface – often alongside a father, uncle, even grandfather – was the ultimate ambition. Colliers were an elite workforce. Status and hard work apart, it also meant top pay, especially when working with a good team of men on a productive face. After nationalisation of the industry in 1947 the job of a collier was defined as:

Getting and filling coal on to a conveyor or into trams [tubs]; getting and filling coal, setting necessary supports, on either machine-cut or hand-got faces; hewing coal by hand-got methods; engaged on stall work and responsible for taking forward rippings, etc., carrying out any operation in connection with a mechanized heading or longwall face; hewing coal with pneumatic picks; developing headings in coal preparatory to opening out stalls.

Coalface-related jobs included that of a ‘ripper’, who would make and brush roadways to obtain a suitable height, erect supports, bore shot holes, load materials and assist getting coal by hand. Other key jobs included that of the ‘packer’ (who built pillars or blocks, using stone and dirt to support the roof in the waste area or roadway), ‘timberman’ (who set wooden props as supports), ‘cutterman’ (working the coal-cutting machine), ‘gummerman’ (dealing with waste material after cutting), ‘borer’ (drilling shot holes), ‘conveyor loaderman’ (loading coal from conveyors on to tubs), ‘fanman’ (operating ventilating fan at the face), and so on.

Getting the coal varied tremendously due to geological conditions. The type of coal, angle of dip, faulting, thickness of seams and working conditions, including high temperatures and wetness, were all crucial factors affecting extraction. Many colliers adapted remarkably well when working in low and awkward seams. Some were ‘complete colliers’ in the sense that they worked alone with little light, many yards from any help or companionship, setting timber props as they progressed each shift.

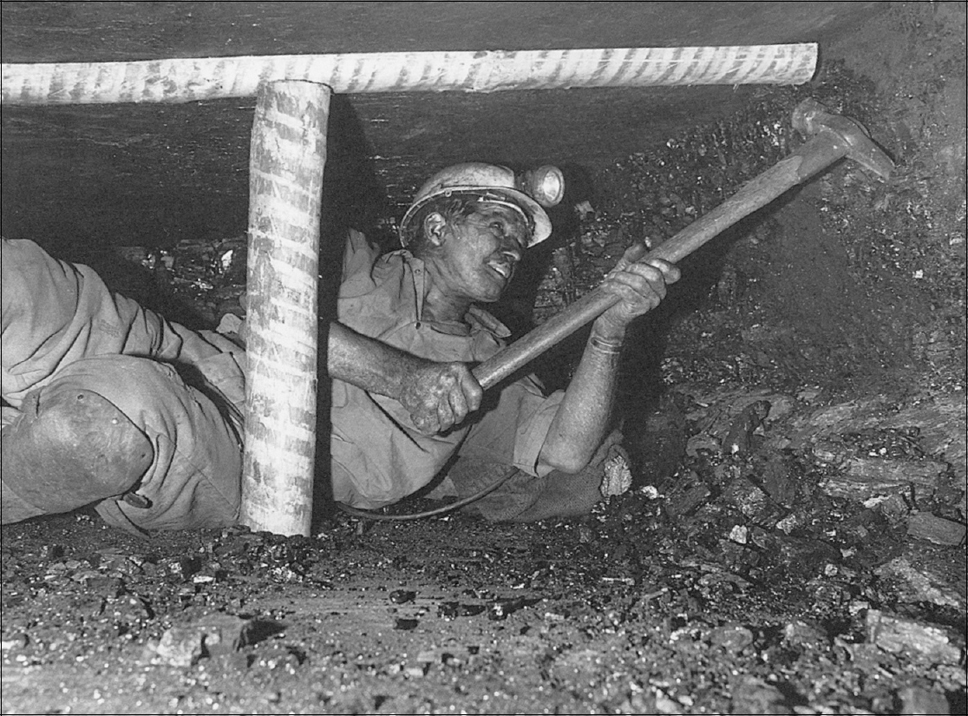

A Yorkshire NCB photographer, Jeff Poar, captured traditional hand-got coal getting (or ‘hand-filling’) at Emley Moor colliery in 1983. The Beeston seam here narrowed to only 16 inches (40cm) high and could not be worked by machine. The collier, 59-year-old Reuben Kenworthy, worked most of his shift laid on his side and belly, a pad of cloth the only protection against the floor, using a pick and shovel to get the coal. He was replicating the kind of work that your collier ancestor would have done many generations earlier. Coal extraction was achieved via the power from the muscles in his arms, chest and stomach, combined with years of skill; and from time to time his back would snag against the roof. Reuben worked continuously for three hours until ‘snap-time’, then took a 20-minute break, then it was back to work in a ridiculously confined space for a further four hours. In this way he extracted twenty-two tonnes of coal on average per day (approx 2,500 shovelfuls!), an extraordinary achievement. The seam record, however, by a Polish miner, Marion Rokicki (or ‘Rocky’!) was almost forty tonnes a day. The legendary Rocky never missed a day’s work, travelling seventeen miles on a bus to get there every day, even walking it in bad weather, producing over a quarter of a million tonnes of coal single-handedly as a traditional collier.

Reuben Kenworthy, when offered a more comfortable job on a higher face, refused, saying that he was used to working in the old way. To get to his place of work, after a 120-yard shaft descent, he had to take a 600-yard ‘man-rider’ journey, precariously laid on a conveyor belt, which was also used to carry materials. Then there was a 20-minute walk and crawl to the face. Preparation work, that is undercutting the dirt below the coal, had been done by a machine, as had some blasting by the shot-firers to loosen the valuable coal.

The use of electronic coal-cutting machines, hydraulic roof supports, and great machines known as shearers, greatly increased production at coal faces, though the noise, dust and dirt generated had to be dealt with as part of the health and safety process.

Reuben Kenworthy at work on the Beeston sewn in 1983. (Jeff Poar)

The recollections of old miners provide us with wonderful insights into the organisation, type and conditions of work in the premechanisation era.

Jack Steer (b.1890): It was hard work. I wore a pair of pit pants, nothing else apart from shoes as it was so hot. The sweat ran down my chest. I’ve seen colliers take their pants off to wring them out. Every collier had his own way of getting the coal. It wasn’t just strength as you used your brains. An experienced collier would cut out one side, cut underneath and over the top, but a strong man might just use brute force, but would achieve less. You would work on your stomach, ‘spragging’ (supporting with timber) the coal to hold it up and then knock the sprags out and the coal would fall. When cutting you had to lay on your side with room just to swing your pick. You kept putting sprags under, until about 5 foot, then knocked them out and it was then easy coal to chuck on. This was the old method of ‘holing’ as they called it.

Tommy Henwood (b.1911): I worked in the New North East face, a Barnsley seam, which was 5ft 6 in. You had to fill a stint [in a shift, say 3 cubic yards] of coal. I used a pick and shovel, hammer and wedge and a ringer [long bar]. At the bottom by the floor we put wooden blocks under the coal and knocked them out and put wooden props up so we could get cover and knock the props out and the face would come down. If the props didn’t hold then you got out of the way fast. I have been buried up to my neck but when mechanisation came steel props came in. We preferred timber as they would split and crack to warn us.

George Rawson (b.1913): Four men worked a pillar of coal or stall, two on day shift and two on afternoon shift. They had to hew under the coal with picks. There was no shot firing. After holing under the coal, by lying on your side, iron wedges were driven into the top pillar of coal to make it leave the roof, then the coal was broken up with a sledge hammer. One of the hammers was bigger than the other and was called a ‘Monday’ as no one liked using it after having a weekend off! The coal was then filled into tubs and the tubs taken by the pony driver to the pass-by where they were sent to the pit bottom by the rope haulage. Hand filling and hewing was very hard work.

George Kemp (b.1920): I would sneak on to the face to the colliers and help them, learning how to go on. I progressed to become a collier when I was 19. The Silkstone was about 2ft 8inches in height. Faces were 200 yards long and ten men worked up at the top side and ten at the low side. You worked on your knees. Getting to your place, you each had 10 yards of coal, about 14 tonnes, to shift. This was a stint. You carried an oil lamp, an electric lantern, a pick, shovel and hammer. You got rid of the gummings [waste] so that it would be higher to work in. The face was prepared for us by the previous shift by the shot-firers. By 10 you felt buggered but three or four slices of bread and fat would revive you. We did not leave the face but occasionally went to the tailgate to have a stretch. Going to the toilet, well you just had to manage where you were working, shovel it into the gob [waste area] and cover it. You could not do anything else. Some might do it on a shovel and put it on a belt but this was not fair on the lads working on the screens!

Bathing and women’s work in the home

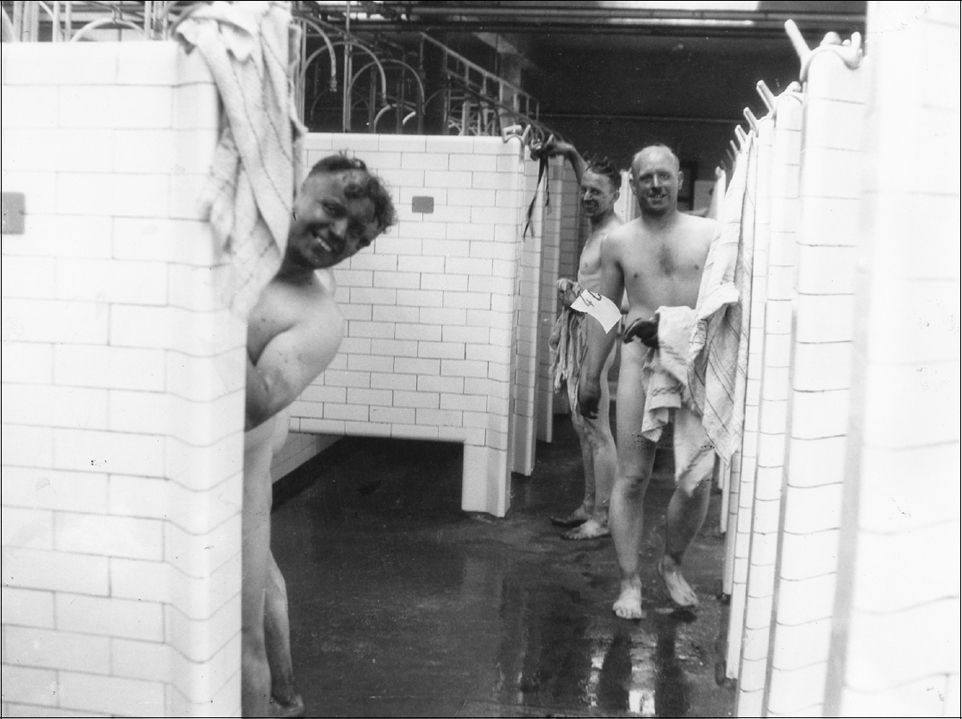

The pit-head bath was full of naked and chattering males of various ages. Almost every bare body there was slim and well shaped. Very few pitmen are ever podgy; their work and bending see to that. New energy and cheerfulness stir our bodies as the hot shower sluices the coal dust downwards in black streams.

B.L. Coombes, Home on the Hill. An autobiography

(1959: unpublished)

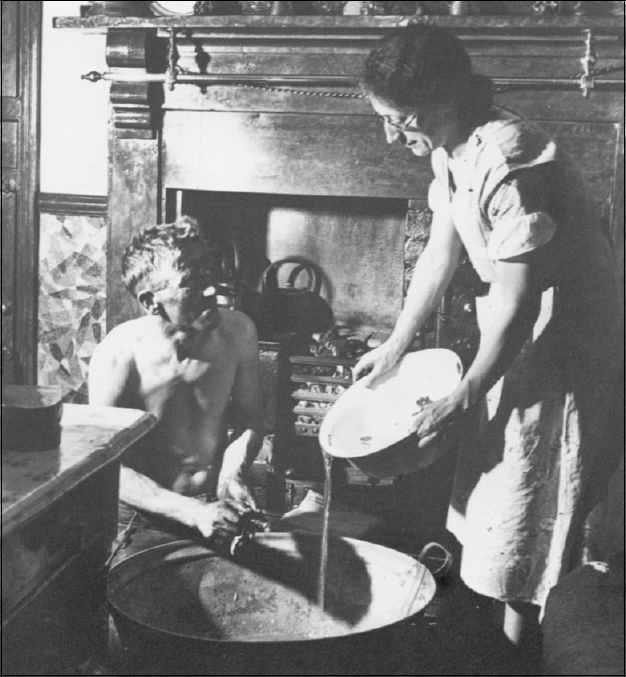

As a small boy growing up in a Yorkshire pit village I can still remember a few black-faced miners coming home from work in their ‘pit muck’, despite the provision of colliery pithead baths. For generations miners had little option but to strip to the waist and bend over an oval zinc bath or bathe in a tub in front of the fire or in the backyard after each shift. What a job it must have been to wash away so much muck and grime. The role of women in this process should not be underestimated! Meal-making apart, mothers, wives and sisters would spend many hours in preparation in a household that might include anything from three to ten or more male miners coming home at three crucial shift times: days (about 2pm); afters (about 10pm) and nights (about 5am). Goodness knows how they coped when several men and boys arrived home at the same time. As each shift ended water had to be heated in the ‘copper’ (an integral boiler) or in receptacles placed on the fire in readiness to fill and replenish the bath. What’s more, the water had to be carried in enamel bowls or jugs to the bather, a back-breaking daily chore; and women were expected to scrub the man’s back (though the superstition of avoiding this as it ‘weakened the spine’ may have persisted for some old miners). Many women developed arthritic and other problems in later life, and even suffered miscarriages. Scalding was also common, occasionally with fatal consequences. Allied to this work was the endless task of the drying of damp pit clothes and associated wash days, which for large families must have taken many hours. In a very real sense women were the unpaid home workers of the coal industry.

The provision of pithead baths – often viewed suspiciously by miners at first – was undoubtedly one of the most important social and practical innovations of the industry. And linked with this development was the provision of canteens and medical rooms, staffed by a ‘pit nurse’ and/or ‘ambulance’ man.

Filling the old ‘tin bath’ with hot water was a backbreaking and potentially dangerous task for women.

In the showers at Woolley Colliery, near Barnsley. The pithead baths here opened in 1939.

Further reading: Ceri Thompson, The Pithead Baths Story (National Museum Wales Books, 2010); Brian Elliott, ‘Muck and grime. Home and pithead baths’ in Memories of Barnsley [magazine], Issue 25, Spring, 2013.

Pithead baths

• The 1911 Coal Mines Act stated that if two-thirds of mineworkers submitted a request for pithead baths (and were willing to pay half the cost of maintenance), the owners would build them, provided the upkeep was no more than 3d per miner.

• The Sankey Commission (1919) recommended that pithead baths should be provided at collieries.

• The Mining Industry Act (1920) inaugurated the Miners’ Welfare Fund, which enabled money to be allocated for the erection of pithead baths.

• By 1936 pithead baths were built or planned for 244 collieries, making provision for 304,000 men and 592 women (female baths were needed in some coalfield regions for ‘pit-brow lasses’).

• The term ‘baths’ was a misnomer as the washing facilities were in fact showers.

• A key feature of the interior design was the separation of clean and dirty locker areas.

• Miners were issued with ‘how to use the baths’ handbooks by each pit after the official opening.

• For cash, miners could purchase bathing items such as soap, towels and sandals.

• The new baths were usually contained in architect-designed modernistic buildings.

Officials: deputies and overmen

Some experienced miners (usually with at least five years’ underground experience, including two years’ facework) either aspired or were encouraged to take on a more senior role at their collieries, as an ‘official’ or deputy. Becoming a ‘shotfirer’ was regarded as a step to becoming a deputy. Occasionally known as a ‘fireman’, a deputy was responsible for the safety of the men in a specified area or district of a mine. It meant obtaining suitable qualifications, through attendance and examination at a mining college or mining department in a technical college. A deputy also had a supervisory role and his yardstick was a symbolic as well as practical badge of office. An overman was a senior official responsible for a larger underground area of a colliery, say two or more districts, an intermediary in status between a deputy and under-manager. From 1910, deputies and overmen had their own national union, the National Association of Colliery Overmen, Deputies and Shotfirers (NACODS).

Officials’ stories

Tommy Emms (b.1911): At age 22 I had a lot of mining experience and one of the managers came round and told me he was looking for officials. I was asked if I would consider becoming a deputy. I had not done very well at school but was told I would be taught how to go on. I was asked to go to Edlington night school and Doncaster Tech for the examination which I passed aged 27. First of all I was a ‘pit bobby’ going around the face and checking for any hidden props, which were valuable items. I had to find them and tell the men to dig them out. I carried a bullseye lamp with a bright light that shone a long way. I did this for six months and then trained on the face and became a deputy. I had a lot of respect when I was a deputy. I always asked the men questions and they gave me questions. That’s the way we got on. Learning their way and they learning my way. I had forty-five men to look after on a shift. I set the men off, with my book, six front rippers, six tailgate rippers, fourteen to sixteen putting packs in, men boring holes, cutter men and so on.

Sydney Cutts (b.1919): I witnessed many accidents because when someone got hurt I was called for … there were some really bad ones. One young chap was killed on the face … he’d been sat down and had not noticed the roof coming down and was buried with his head on his knees. You almost got hardened to it. Deputying was a lot of responsibility. I was as soft as a boat with the men at first. Some deputies could be bullies but I let the men know I was one of them, not one of the upper crust. I would help if someone was behind, give them a hand, especially the old ‘uns. Later I became an overman. I was well liked by the men as I did not believe in pushing them too much. If I saw someone getting a bit extra or a bit less then I would sort it out. We looked after about three districts and helped each other (overmen). We had to see the manager after each shift. I would sooner have worked with the men. We had a rough time going to the pit to examine things during strikes but we had to check on safety. We refused to do anything else. Most of the men were great, just like brothers.

Eric Crabtree (b. 1932): A good official has to be able to organise the work well and have good eyes to know what needs doing. You also needed to be able to handle men. I gave the men an hour’s overtime for a big job and got them together in the conference room to discuss the job, and also asked for suggestions. This was much better than ordering people about. I treated men as my equal and got a lot of respect as a result.

Under-managers and managers

Colliery under-managers and managers in the modern era not only had wide experience of the mining industry, but also had to have a variety of qualifications under various mines Acts. Many were also members of professional bodies. They were responsible for safety and production in part of or for the entire mine.

Tip

A managers’ database at the North of England Institute of Mining, and Mechanical Engineers (NEIMME) in Newcastle is currently under development and members’ lists can be seen in the back of the proceedings of the National Association of Colliery Managers held at the NEIMME (www.mininginstitute.org.uk).

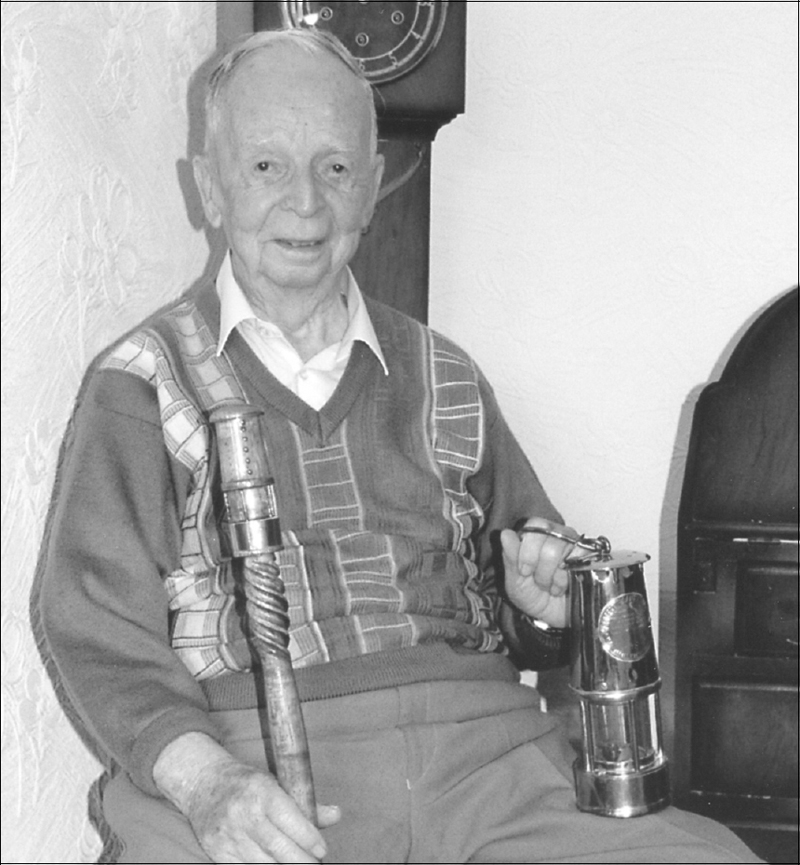

Screen lad to Manager, Inspector, Mining Engineer and Director

Bernard Goddard (b.1917) started work on the pit-top screens at Grange colliery, near Rotherham, at the age of 14. Whilst still in his twenties, through study and examination, he had obtained deputy’s, under-manager’s and manager’s certificates, attending day and evening classes. Aged only 31, he was appointed His Majesty’s Inspector of Mines for the Northumberland, Durham and Cumberland area, the youngest mines inspector in Britain. After five years Bernard returned to colliery management in Yorkshire, eventually becoming Chief Mining Engineer and and Head of Production for the NCB South Yorkshire and Doncaster areas. His career then extended to that of Director (and spokesperson) of Mining Environment, with offices in Doncaster and London. Bernard’s senior role with the NCB involved visiting many European countries, as well as North and South America and the USSR, and working with leading figures in the industry, including the NCB chairman, Derek Ezra and miners’ leader Joe Gormley. After official retirement Bernard worked as a mining consultant, his total mining experience extending to almost sixty years.

Bernard Goddard.

Mining engineers

Mining engineers were of vital importance for the operation and development of mines, as well as for safety and emergencies. Professionally qualified, via regional institutions, they usually worked within or had their own independent practices, and were used on a consultative basis by the colliery companies, swiftly so during times of crisis. Mining engineers were referred to as ‘viewers’ in the nineteenth century.

A biographical database based on information held in the Transactions of the Institution of Mining Engineers is available for consultation in the library at the National Mining Museum for England at their Caphouse colliery site near Wakefield (www.ncm.org.uk/collections/library or email: curatorial.librarian@ncm.org.uk). The database, which covers the period 1889–1983, concerns the more prominent members and includes reference to obituaries, photographs etc. Transactions and printed material relating to some mining engineers are held at the Institution of Mechanical Engineers in London (www.imech.org), as well as other places referred to in the reference section of this book. For high-profile managers and mining engineers do also check the DNB (Dictionary of National Biography) as there may well be an entry.

Parkin Jeffcock, civil and mining engineer (1829–1866)

On 12 December 1866 a telegram from Barnsley reached the office of Thomas Woodhouse, mining engineers, in Derby. It read: ‘The Oaks pit is on fire. Come directly’. Woodhouse was unavailable, so Parkin Jeffcock, the younger partner, set off by train to Barnsley. Assisting with the rescue operations in terrible conditions, Jeffcock was one of twenty-seven brave volunteers who lost their lives after a second underground explosion the following morning. This pushed the total fatalities to 361, making it Britain’s worst-ever mining disaster. Jeff cock’s body was not recovered until 5 October 1867, identified by his name on his shirt tag, and he was then buried in Ecclesfield churchyard. Jeffcock attended the College of Civil Engineers at Putney and trained under an experienced Durham viewer and engineer, George Hunter, becoming a partner in the Woodhouse practice in 1857. St Saviour’s church at Mortomley, near Sheffield, was built in Jeffcock’s memory. A spectacular memorial to Jeffcock and other Oaks volunteers can be seen overlooking Doncaster Road at Kendray, near Barnsley, erected there in 1913.

As we have already seen, from the nineteenth century onwards there was a great diversity of jobs at coal mines. Undoubtedly one of the most specialist and most dangerous at the start-up stage was that of the pit sinker. Once a mine location had been carefully chosen (after test bores) and the site marked, by a ceremonial ‘cutting of the sod’, a small, very distinctive team of workers – usually employed by a specialist contractor – arrived to begin the long and dangerous process of sinking. Led by a master sinker, these men might spend a year or two (even longer sometimes), maybe living in lodgings until the task was complete and then move to the next job. Like pioneer gold miners, they sometimes lived in flimsy huts during the sinking process, prior to the great influx of miners into the area. At Dinnington, in south Yorkshire, for example, the sinkers lived in impromptu properties made of corrugated steel sections, located near the pit, an area that became known as ‘Tin Town’. However, it was not unusual for some sinkers to live in purpose-built cottages near their place of work, occasionally identified on large-scale maps as ‘sinkers’ row’.

Early shafts could be little more than a few feet in diameter and quite close to each other, but from about 1850 usually extended to several yards, enabling a pair of substantial cages to be accommodated. However, shafts were not just for winding men, materials and coal, but also had to be suitable for ventilation, pumping, power and communication (signalling).

Starting off was relatively easy, even in the pre-mechanised era, manually digging through the top and sub-soil until the rock strata was reached. A large iron sinking bucket was used to contain the waste material, and for inspections. On occasions, due to the confined space in the bucket, several sinkers had to dangle one of their legs over the side during precarious descents and ascents. The bucket was suspended, lowered and raised via either a crane and jib at the surface or a basic pulley-frame system. Temporary timber lining was often used to support the shaft sides, and then replaced by brickwork (and in later years by cast iron or concrete blocks). There was immense danger during the whole process, especially from falling rocks and inrushes of water. Accidental explosions and gas emissions were further hazards to contend with, blasting being used to loosen rock as sinking progressed; and of course as work proceeded there was always the real prospect of falling down the shaft to a certain death. Safety was always undermined in that the sinkers were usually paid ‘per yard’ of progress.

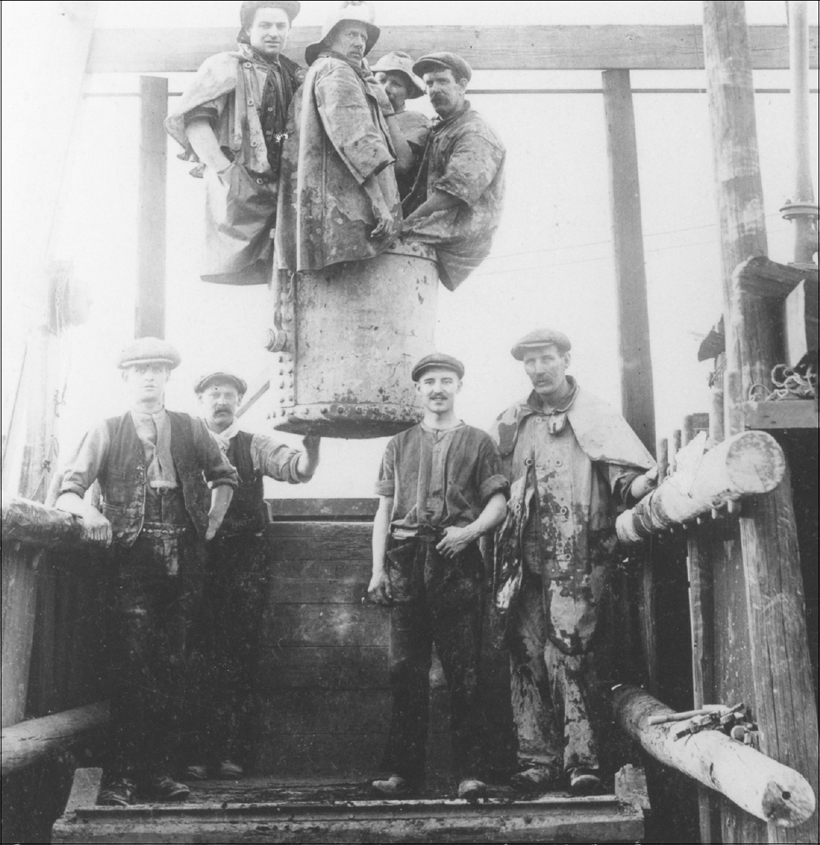

Early photographs showing pit sinkers in dangerous situations, standing on platforms and clinging to buckets, with little protection other than oilskins, are perhaps the most compelling images of mining.

Initially ignoring planning regulations, the legendary Lancashire steeplejack and television personality Fred Dibnah (1938–2004) sank a 30m brick-lined mine shaft in his back garden in Bolton during his last series, in 2003, using many of the old skills of the pit sinkers.

Tip

Peter Ford Mason’s The Pit Sinkers of Northumberland and Durham (The History Press, 2012) is essential reading if your ancestor was a pit sinker.

Thorne Colliery: a sinking nightmare

Set in the flat land east of Doncaster, barely above sea-level, the sinking of Thome Colliery must rank as one of the most difficult, most prolonged, most expensive (£1.5 million: about £45 million today) and most tragic engineering tasks in the history of modern British mining. Progress on the two shafts was beset with flooding and technical challenges that spanned the First World War and was not completed until 1926, after seventeen years of stop-start work. During the early phases of sinking one man was killed when he fell from the hoppit (sinking bucket); another worker died from carbon monoxide poisoning; and on 13 December 1910 a sinker was killed and seven others injured when a pump fell down the shaft, crashing through a work platform. But mishaps climaxed in the early afternoon of 15 March 1926, during the final stages of sinking. Six men were hurled to their deaths when the scaffold on which they were standing collapsed following the failure of a supporting engine on the surface.

Engine winders

An extremely important occupation at the pit-head was that of the engine winder, who was responsible for operating the steam-powered (and later electric-powered) engine that hauled the single or multi-decked cages of men, coal and materials up and down the shafts. Before the 1842 Mines Act a boy as young as 12 years old could work as a ‘winder’ and accidents were not unusual. The minimum age was raised to just 15 after 1842. Subsequent safety measures, regulation and inspection were of massive importance, the operators subject to severe interrogation after accidents and mishaps, at inquests, inquiries and in courts, where criminal prosecution might be faced. It was not unusual for winders to be in the job for many years, keeping the role in the same family over several generations. Winding engine houses were usually kept in immaculate condition via the engine-man and his assistants. This small but vital group of workers had their own local unions or associations and, from 1878, national representation through membership of the National Union of Winding and General Enginemen.

Pay

Prior to national agreements, the calculation of miners’ pay was complicated, though the actual process was fairly straightforward, at least for much of the twentieth century, and for a good number of years earlier too. Pay-day was usually on a Saturday after the last weekly shift, and then on Fridays when five-day weeks were established. The usual procedure was for the miner to go to the pay cabin/office and exchange a numbered pay check for cash earned during a set period, say a fortnight. At some pits the money was handed over via small numbered tins. A pay summary sheet or strip usually accompanied the cash, showing what had been earned, along with stoppages, which might include deductions for contributions to hospital and relief funds, insurance and so on, and even materials, such as explosives.

However, in some regions many miners worked under a sub-contracting or ‘butty’ system, where an experienced man such as a collier had an agreement with the management/coal owner/coal company, to pay out a group of men. Pay-outs might take place in the pit yard or a convenient location nearby. My grandfather, Fred Elliott, got paid – rather temptingly – in the yard of a pub about half a mile from his colliery. On occasions my father would be dispatched to the location to make sure that he did not go into the pub and spend some of his wages, every penny being required for a family of eight. Weekend ‘binges’ did take place, of course, and the first Monday morning back at work after a fortnight’s pay-day was never the best-attended shift.

Before about 1850 miners were often subjected to a signed and witnessed hiring agreement, known as the yearly or monthly bond, in exchange for a nominal wage. Akin to a master and servant arrangement, the bondage system was rightly regarded as slavery, and was particularly vicious and prevalent in Scotland and the northern coalfields during the eighteenth century. Miners breaking their agreement could be blacklisted, or even transported. The truck or ‘Tommy’ system was widespread in some areas, with mining families having to purchase basic food and commodities from the colliery companies/owners via the issue of pay in the form of tokens.

Miners were usually paid through piecework, performance-based work agreed between the miner and/or union and the mine manager/company. Typical examples would be based on the amount of coal extracted (per ton or cubic yard removed) or the yardage of advance during the making of a heading. Labourers, however, were paid a daily wage.

After 1911, performances for piecework depended on locally agreed (between management and miners associations/unions) documents known as Price Lists, small booklets containing the rates of pay for working in different seams of coal in a named colliery or area. The lists included rates for ‘boys’ working underground, aged 14 to 23 (later amended to 21). The various miners’ associations and employers also published joint booklets relating to minimum wage rates for men and boys, following the Coal Mines (Minimum Wage) Act of 1912.

An elected and union/workers’-paid pit-top worker known as a check-weighman was a key pit-top figure when miners were paid by weight of coal, monitoring the calculations of the mine owner’s weighman at the weigh house.

From time to time the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain published average wage lists, according to various classes of workers. The largest and best-paid category (with 350,000 members) were ‘piecework getters’, colliers in the main, who got almost 9 shillings in 1914, rising sharply to 21 shillings in 1920 after the substantial Sankey Commission award. ‘Underground labourers’ (163,800) were ranked sixth in the wage table (after day-work getters, fillers, timbermen and deputies), receiving just over 15 shillings after Sankey. Youths and boys working on the surface (42,120) were joint bottom of the listing, with a post-Sankey wage of 7s 6d, the same average earnings received by the smallest category: 3,030 mainly ‘pit-brow’ women and girls.

Pay days recalled

Jack Steer (b.1890), a collier: I was employed by a contractor who was in charge of the haulage system. He paid me from a kitchen window in Ranskill Road [Sheffield], The collier paid you if you worked for him. You got 6 shillings a day for filling and he would keep what was left over. If I earned £1 he would get 14 shillings and I would get 6 shillings. If there was a filler short the deputy would send you elsewhere. Once I had to work on five different stalls so had to go to five different pubs to get my wages. In 1932 a filler still only got 8 shillings a day. The pit was on a four-day week, which meant a 32-shilling wage.

Gerald Booth (b.1909), pit-top haulage worker: It was a day wage, 13s 7d a week at 14 and a shilling rise each birthday. Saturday was pay day. We went to the pay office and received our money in little tins after handing in a pay check.

Stan Potter (b. 1922), trammer and collier: The best thing about mining life was pay day!

Frank Johnson (b. 1922), collier: The best thing about nationalisation was that everyone got the same rate of pay.

Frank Beverley (b.1923), screen lad and underground haulage boy: We had ‘tipple tin day’. On a Friday you went to this window where there was a bob hole, and you put your hand in. On the inside there were little tins with money in and the bloke might say, ‘Tally number 1322’ and put number 1322 tin in your hand. It was 10s a week, which I gave my mum. Then it rose to 12s 6d and Mum gave me 2s 6d back.

Bess and Ralph Anstis, The Diary of a Working Man. Bill Williams in the Forest of Dean (Alan Sutton, 1994)

Harold Brown, Most Splendid of Men. Life in a [North Staffordshire] Mining Community 1917–25 (Blandford Press, 1981)

Jim Bullock, Bowers Row. Recollections of a Mining Village (EP, 1976)

B.L. Coombes, 1 Am a Miner (Fact, 1939)

B.L. Coombes, Miners Day (Penguin, 1945)

B.L. Coombes, These Poor Hands – The Autobiography of a Miner Working in South Wales (Victor Gollancz, 1939)

David Douglass and Joel Krieger, A Miner’s Life (Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1983)

Brian Elliott, South Yorkshire Mining Veterans (Whamcliffe, 2005)

Fred Flower, Somerset Coalmining Life (Millstream, 1990)

John Graham, A Miner’s Life (Tyne Bridge Publishing, 2009)

Michael Pollard, The Hardest Work Under Heaven (Hutchinson, 1984)

Ian Terris, Twenty Years Down the Mines (Stenlake, 2001)

Mary Wade, To the Miner Born [Bedlington] (Oriel Press, 1984)

Maurice Woodward, A Coalville Miner’s Story (Alan Sutton, 1993)