RIGHTS AND STRIKES: ASSOCIATIONS AND UNIONS

From the middle decades of the nineteenth century many coalminers were members of district unions and regional ‘associations’. Before 1945 and the formation of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) all coalfield areas had a variety of unions, some so local as to represent men at a single colliery or village. Many were short-lived, some merged and others amalgamated or became part of federations.

Do bear in mind that some owners did not allow or like their employees to be union members and it was not unusual for some of the more outspoken miners to be sacked and ‘blacklisted’. This chapter provides an overview of the miner and his (and occasionally her) union, which was an integral part of their working life.

In the early days, as with friendly societies, being in a union was a form of family insurance against hard times when illness, injury, handicap or old age reduced or prevented work. Grievances apart, just having someone to talk to at work or the branch (or ‘lodge’) meeting held in the pub or working men’s club was an immensely important social benefit, even in retirement. Mutual support and friendship were the fraternal and symbolic components of the backbone of union membership, as was a vision to change to a more equal and just society. Miners’ unions were also of course an integral part of the labour movement as a whole.

‘Eddie’ Collins (b.Wombwell, Barnsley, 1894), lodge secretary at Denaby Main for twenty years, recalled his union background:

I joined the union when I started work at the pit [Cadeby Main, near Doncaster], Young lads had only threepence to pay, then it went up to sixpence a week. My father paid a shilling. My father was always in the union. I used to go and pay the union for my father when he worked at New Oaks colliery. They paid it at a Saturday then … I was a young lad of nine or ten … He was never in arrears … Eventually, in 1934, when I became branch secretary … there was just over 1,200 in the union, and we’d about 2,200 workmen, and I thought, ‘That’s got to be altered,’ so I used to be standing at the pit gates and asking them to join the union. I got men to join, and we had above 2,000 members before 1936.

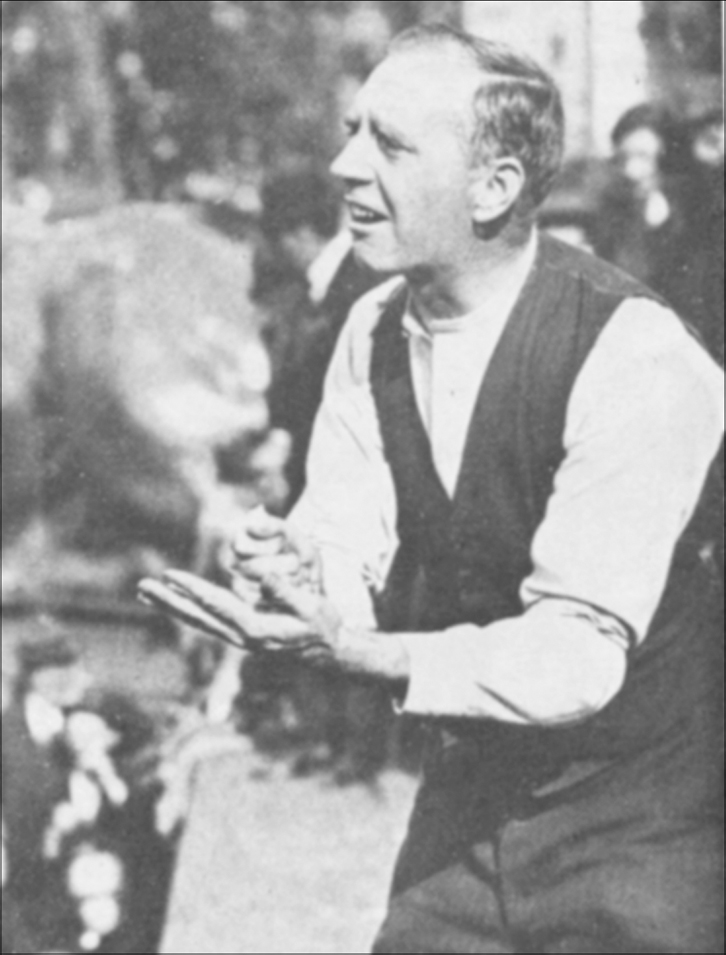

Collins also served as a ‘workmen’s inspector’ under the 1911 Coal Mines Act, representing the miners on safety issues. Politically active, as chair of the Minority Movement in Yorkshire and founder member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, he managed to arrange for the militant socialist and Welsh miners leader Noah Ablett and the charismatic A.J. Cook, Secretary of the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain, to speak at the Denaby branch. His final working years were spent as Compensation Agent for the Yorkshire Area NUM in the Miners’ offices in Barnsley.

(Jim McFarlane, ‘Denaby Main: A South Yorkshire Mining Village’, in Studies in the Yorkshire Coal Industry [Manchester University Press, 1976].)

‘A.J. Cook’ (Arthur James, 1883–1931) as he was generally known, is regarded as one of the most important of all miners’ leaders. Somerset-born, Cook rose to prominence as a full-time union official in south Wales after working as a miner in Merthyr Tydfil. A lay Baptist preacher, ‘Cookie’ was a brilliant speaker. He was elected as General Secretary of the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain, serving until his premature death in 1931 and was a key figure during the 1926 General Strike and miners’ lock-out.

Major issues such as pay and working conditions were dealt with through representative negotiation with management and owners. Rates of pay before nationalisation were largely fixed through complicated ‘price lists’ on a colliery and area basis. In some extreme circumstances miners and their families were evicted from their company-owned houses resulting in exceptional distress. There are several examples, but two of the most astonishing cases of extreme action by owners occurred within a few years in the Yorkshire coalfield, at Denaby Main (1902/03) and Kinsley (1905). The disputes attracted national media coverage as well as parliamentary debate. Keir Hardie, the indefatigable pioneer Labour leader and MP for Merthyr Tydfil, visited Kinsley and, ‘banners flying’, there was a major demonstration at May Day Green, Barnsley in 1906, with speeches from miners’ leaders.

During the twentieth century, and especially after the formation of the NUM in 1945, a wide range of benefits were available for members. Practical help following accidents not only included compensation assistance, but also the provision of convalescence facilities. The long battle to obtain compensation for the long-term respiratory and associated illnesses has continued to the present day, though not without controversy. One other underrated role of the NUM has been the provision of education and training, for example at Day Schools, for its officials and members.

Union development c.1780 onwards

Before the 1830s, small ‘associations’ of miners lacked any organisation for effective bargaining power and had limited success against the owners and an unstable market for coal. The use of special constables, soldiers and the reading of the Riot Act stamped on protest and underlined the fragmentary ineffectiveness of local combination. In south Wales Richard Lewis (better known as Dic Penderyn) paid the ultimate price in 1831, hanged outside Cardiff gaol for the apparently false accusation of stabbing a soldier in the rising at Merthyr on 3 June. Towards the end of the decade Chartism demonstrated that miners had a common ideology, beyond local and area boundaries. The search for national unity began. It proved to be a very long and rough road, starting at Wakefield in November 1842, with the albeit short-lived Miners’ Association of Great Britain and Ireland.

If your coalmining ancestor worked from the 1850s to the 1870s he was probably a member of one of the many district unions. The moderate Miners’ National Union (MNU) gradually lost support from most of its affiliated areas, its falling membership concentrated in Durham and Northumberland. However, under the leadership of Alexander McDonald, the MNU played a decisive role campaigning for better conditions of employment and safety through the Coal Mines Regulation Act of 1872. The districts came under great strain after the great fall in coal prices during 1874 and wage reductions sparked off disputes and strikes throughout the coalfields. A variety of contentious ‘sliding-scale’ pay arrangements were introduced, and the bargaining strength of the miners weakened.

A miners’ federation initially comprising the county associations of Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, Lancashire, north Wales, Staffordshire, Warwickshire and Leicestershire was formed in 1889. The Miners’ Federation of Great Britain (MFGB) soon attracted affiliation from the Scottish and south Wales miners, and also from Northumberland and Durham. With a membership of 600,000 the MFGB could claim to represent all miners, but the situation remained complex. The deputies and craft unions (winding enginemen, mechanics, firemen etc) remained largely separate and in 1910 there were still seventy-four independent coalmining unions in existence. The South Wales Miners’ Federation (founded in 1898 and known as ‘The Fed’) with 137,553 members became the largest constituent of the MFGB. Durham Miners’ Association were not far behind (121,805) and well ahead of third-placed Yorkshire (88,271).

The fragmentary state of coalmining unions hardly helped solidarity during the 1926 strike and its aftermath, including the breakaway ‘Spencer Union’ in Nottinghamshire. After the Second World War the inauguration of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) on 1 January 1945 took place just at the right time, with a new and reforming Labour government coming to power, just two years before the nationalisation of the industry under the National Coal Board. At last the miners had a single voice and a single negotiating partner. The NUM membership was substantial at 533,000; two officials’ and deputies’ unions had a combined membership of 23,133 and there were a few hundred in a winding enginemen’s union.

During the 1960s, when Lord Robens was Chairman of the NCB, about 400 pits were closed and half of all the miners lost their jobs. The massive run down and virtual eclipse of the deep-mining industry following the 1984/85 miners’ strike now means that NUM membership has declined from around 180,000 to less than 2,000. Nevertheless, the NUM, with its historic headquarters in Barnsley, continues to operate and represent its members past and present on a federal basis via the main old coalfield areas.

Strikes and lock-outs

Miners were always one of the more radical groups of industrial workers and from the eighteenth century every coalfield had its ‘turn-outs’, shortterm strikes or withdrawals of labour, with the main areas of Northumberland and Durham, south Wales and Yorkshire more prone to longer and more frequent agitation. Disputes were often very local and short-lived, lasting a shift or a few days, but others continued for weeks and months, spreading to other coalfields. ‘Lock-outs’, where the coal owner or company barred its miners from returning to work were not uncommon. Your mining ancestor is therefore highly likely to have been involved in one or more industrial disputes during a working life.

Tip

Local newspapers are an excellent source of information on industrial _ disputes and it is well worth taking a sample few years just to get an impression of the ‘militancy’ of the area in and around where your ancestor lived. Build up a ‘context’ file and it will help you appreciate what issues may have affected your miner (and of course his family). Reportage of the meetings of the miners’ associations is particularly useful and the ‘local news’ sections may even include information about events at branch/lodge level. Do also check the ‘magistrates’ court’ pages too! One commonsense word of warning about actual strike/lockout accounts: newspaper editorials and reportage varied according to the political slant of the editor/owner. So do read more than one source.

Personal, eyewitness reports are invaluable even though you may not have anything direct from your own ancestor. And don’t forget to include the contributions from women. Autobiographies, published and in typescript, often lodged in local studies and archive libraries, are well worth consulting, as are any relevant oral history recordings or transcripts. For the 1984/85 strike a massive amount of material has emerged into the public domain over the last thirty years. The role of women during and after the strike was exceptionally important. The BBC regional radio stations and the archived main BBC news site (www.bbc.co.uk) make excellent starts; and a search using ‘miners’ strike’ will direct you to many online sources.

Notable strikes and lock-outs

1893: the ‘Great Lock-out’ affected Yorkshire, Lancashire and the Midlands, from June. Two Yorkshire miners were shot dead (and sixteen injured) in the ‘Featherstone Massacre’ of 7 September when troops opened fire on a protesting crowd following a reading of the Riot Act. The dispute dragged on until the end of November when, after arbitration via a new National Conciliation Board, the owners’ demand for a 30 per cent reduction in miners’ wages was reduced to 10 per cent.

1894: in Scotland, June-October.

1898: in south Wales, over five months.

1902/03: Denaby Main, Yorkshire, lockout and evictions.

1905: Kinsley, Yorkshire, lockout and evictions.

1912: arguably the first truly national coalmining strike; over a million men affected, from late February to mid-April; an often bitter dispute over a minimum wage requirement (in an attempt to deal with inconsistencies concerning pay-rates for coal-getting in different coalfields and districts).

1921: a national lockout, from 1 April (to 1 July) following a return to ‘district agreements’, in effect wage reductions, involving all miners; the Triple Alliance (miners/railwaymen/transport workers) fell apart on Black Friday, 15 April, leaving the miners on their own during a three-month dispute which involved widespread poverty in the coalfields.

1926: a national lock-out from 1 May (and nine-day General Strike from 4 May), following the ‘reduced wages’ Royal Commission report on the industry which the miners felt favoured the owners. The men remained out but by the autumn many thousands had returned to work including the members of George Spencer’s Nottinghamshire-based breakaway union. Bitter recriminations continued for many years.

Miners’ wives and children supporting pickets at Rugely Power Station during the national coal strike, 18 January 1972.

1972: the first national strike for over forty-five years was about pay, a dispute against the NCB and statutory incomes policy of the Heath government. It lasted from 9 January – 28 February and resulted (via a landmark inquiry under Lord Wilberforce) in a substantial improvement in pay and conditions. The strike was noted for co-ordinated and strategic (and so-called ‘flying’) picketing of sites such as power stations and, most famously, at Saltley Gate coke plant, Birmingham, led by a young Yorkshire miners’ leader called Arthur Scar gill.

1974: on 9 February, two days before Parliament was dissolved, 82 per cent of the NUM voted for strike action in support of higher wages. The snap General Election on 28 February resulted in a defeat for the Conservative Government of Edward Heath and a Labour minority government under Harold Wilson came to power. The strike ended on 11 March with the award of wage increases and better conditions of work and employment, though some of the injustices still outstanding from 1926 remained.

1984/85: the last and now often referred to as ‘great’ miners’ strike lasted almost a year, starting in South Yorkshire, from March. Often personalised as a battle between Scargill and MacGregor/Thatcher, experts continue to argue over the background and outcomes of what is now generally regarded as the most bitter and most controversial industrial dispute in modern British history. Whatever the analysis, its legacy is undisputed: the miners’ demise was a precursor of the virtual destruction of deep coalmining in Britain through post-strike pit closures, especially during 1985–1994.

Strike Memories

Ernest Kaye (b.1917), Birdwell, south Yorkshire

The [1926] strike was clog and boot time if you like, not much to wear, no money at all. There was mother and father, me and my two brothers, one of them dying aged ten. Quite a few people gave food to the community. We went to school as normal … some wearing just one shoe … big holes in jumpers … we used to take our pot to school and go across to Birdwell Club and have our tea there, two jam sandwiches and a bun. At the top of our road there were some allotments and one very knowledgeable man decided to sink a pit. A big hole was dug. All the men, colliers, stood around and they went as far down as to think to get some coal … My dad was among them. A big bicycle wheel with a rope on and a bucket was set up and they used to shout ‘Reight, lower it down’.

Barbara Williams, miner’s wife, Maerdy Women’s Support Group, south Wales, 2004

The memory doesn’t go away. It’s as if it was a few weeks ago. We had to form a committee. Somebody said, you need a treasurer and secretary and my friend said, put your hand up and get involved. At the start no one would have envisaged it would have been a year-long strike. We realized there was a fight on, but at the end of the day we were fighting to keep the pit open, for the men to keep their jobs to support their families. I think a lot of women proved there were things they had never, ever done before that we were now capable of doing.

Demonstrations and Galas

Regional gatherings of branches and lodges, leading to an open-air meeting involving speeches and entertainment, became increasingly common from about 1860 and attracted huge crowds. The South Yorkshire Association, for example, held fourteen Demonstrations between 1863–79, mostly at Barnsley, and the neighbouring West Yorkshire union had ten Demonstrations during a similar period (1867–80). After amalgamation in 1881 demonstrations in Yorkshire were held annually (except during 1912–31 and 1940–46). In Derbyshire, the first demonstration was held in 1873. The annual Northumberland Miners’ Picnic, which began in 1866, also attracted a large following. Although there are now no deep mines in the area, the famous Durham Miners’ Gala or ‘Big Meeting’ is still held each second Saturday in July, in Durham city. First held in 1871, in its heyday during the 1950s over 300,000 people were in attendance. In Fife the annual celebration held to commemoration the famous eight-hour day victory of 1870, was in 1947 incorporated with the Scottish Miners’ Gala Day at Holyrood Park, Edinburgh, inaugurated after the winning the five-day week. By 1953 the attendance at the Gala exceeded 100,000. Demonstrations were always well reported in local and regional newspapers and the programmes, photographs and film of the events are well worth consulting in local studies and national libraries.

Banners

Banners were not only used at demonstrations or galas, but also at funerals, especially after accidents and disasters. In recent years they have have formed the backdrop of a variety of commemorative ceremonies and the unveiling of mining monuments. Surviving miners’ banners can be seen in many settings, from working men’s clubs and miners’ welfares, trade union offices and town halls to regional and national museums. In the North East a particularly good display can be seen at the Woodhorn Museum, near Ashington. The South Wales Miners’ Library in Swansea has a collection of thirty-nine relatively modern banners. Samples are usually on display at the national mining museums for Scotland, England and Wales.

The early, hand-made silk or velvet versions are rare, fragile survivals. In most cases the banner you will see is a replacement of one or more earlier versions as they were only expected to have a lifespan of a generation or so. Inauguration was a special occasion. The artwork on the banners includes a variety of social imagery: ‘Steps to Socialism’ or the achievements of the unions and the Labour Party; ‘prosperity and happiness’; ‘health and peace’; ‘five-day week’; ‘nationalisation’; ‘family allowances’; and ‘social security’. From Keir Hardie and Alexander McDonald to Clem Attlee and Harold Wilson, the heroes of Labour are portrayed on many of the banners, as are the great mining leaders: Tommy Hepburn, Arthur Horner, Peter Lee, A.J. Cook, Herbert Smith and, on several of the new banners, modern leaders such as Lawrence Daley and Arthur Scargill.

Was your ancestor a miners’ leader? If not he would certainly have known one. Such men were very important in miners’ working lives, and were also often prominent in matters relating to welfare. And of course some held public office, locally or regionally. In some respects their relatively well-documented lives can also help us to appreciate what it was like to be a miner, as most had worked in the pits from leaving school.

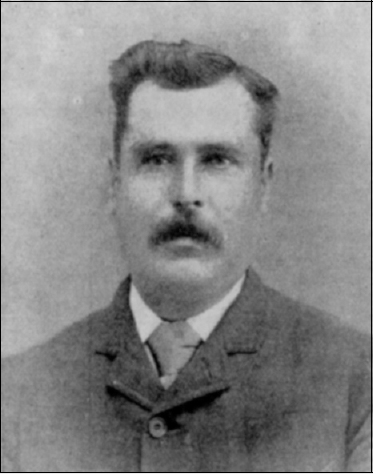

Levi Lovett (1854–1929), miners’ leader

Born at Hugglescote, Leicestershire, his publican parents moved to nearby Swannington where Lovett spent the rest of his life. At the age of 12 he started work at Swannington (No.3) pit but through self-education studied and passed all grades of mining work. Lovett remained as a miner until the age of 32 when he was appointed as checkweighman at Snibston. He helped to form the Coalville and District Miners’ Association (later renamed the Leicestershire Miners’ Association [LMA]), serving as president from 1887 until 1900. His union activities, however, continued, as he worked as secretary and agent for the LMA and as their representative on the executive of the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain. Due to ill-health Lovett resigned as agent in 1923, after thirty-six years of service to the miners of Leicestershire. He had been particularly important in helping miners with their compensation claims. Like most miners’ leaders of this era, Lovett was active in local public life, as parish councillor, president of the village horticultural society, governor of Leicester Infirmary and as a magistrate.

Apart from published autobiographies and biographies, by far the best source for miners’ leaders is the thirteen-volume Dictionary of Labour Biography, a remarkable and ongoing piece of scholarship originated in 1972 by Joyce Bellamy and John Saville (Macmillan Press Ltd) and later by Keith Gildert and David Howell (for Macmillan Palgrave). Most miners’ leaders, however, are contained in the first five volumes. If there is a family connection you can then consult the relevant volume for the biographical entry. Greg Rosen’s Dictionary of Labour Biography (Politico Publishing, 2001) is worth consulting for several of the better-known leaders, as is John Ramsdon’s The Oxford companion to twentieth-century British politics (OUP, 2002 & 2005). For national figures, the Dictionary of National Biography (DNB) is the standard reference work (online via some library services or held at some central libraries). One early but hard-to-find source, containing thirty portraits, is William Hallam’s Miners’ Leaders (Bemrose & Sons, 1894).

Joseph Arthur Hall (1887–1964), miners’ leader

‘Joe’ Hall was born in the small mining community of Lundhill, Wombwell, in south Yorkshire. Here, thirty years earlier, residents experienced one of the worst disasters in British coalmining history when 189 men and boys were killed. By the age of 12 he was working underground, at Darfield Main, replacing burnt-out lamps at the coal face; he then went pony-driving. Moving to Cortonwood, he was set on as a ‘trammer’, hauling full and empty tubs for his paymaster collier. In 1907, Joe Hall was elected to the Cortonwood branch of the Yorkshire Miners’ Association (YMA), progressing to delegate (1910) and secretary (1916). He served as checkweighman at the pit from 1917. By 1925 he became a paid official (financial secretary) of the YMA (which then had a substantial 160,000 membership). In 1930, he was elected as an executive member of the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain (MFGB) and was a key figure at the Gresford (north Wales) inquiry following the disaster of 1934; he gave evidence to the resultant Royal Commission on Safety in Mines. The climax of Hall’s union career was his election as president of the YMA in 1939, succeeding the great Herbert Smith. Joe remained in office until his retirement in 1952. Affectionately known as ‘Our Joe’, centre-stage in the Miners’ Hall at the NUM headquarters in Barnsley is a stone plaque commemorating his services, especially his ‘unceasing efforts to save life at many of the mining disasters in the country’.

Women

Female union membership was very sparse until towards the end of the First World War when women were recruited in significant numbers to work at pit-heads. There were only 290 female miners’ union members in 1896 and 1,041 in 1914, but by 1918 their numbers had swollen to 10,000. Female union labour was spread throughout the main coalfields. In Lanarkshire, for example, there were 2,040 women members in December 1908 (out of a total membership of 48,000). They worked as coal-pickers, haulage hands and saw-millers, earning from about 6 to 15 shillings a day including bonuses, far higher rates than in most other industries. Although female membership was welcomed, it was the policy of the union to get rid of female labour ‘owing to the conviction in members’ minds that their employment about collieries is not suitable’.

Research guide

1. Where to find miners’ union records

What survives is scattered across a range of archives. Some union records may be deposited in your local and/or county record office, so it is always worth a check there as a first step. For regions, see Chapter 9. The National Archives (www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/), National Library of Scotland (www.nls.uk) and National Library of Wales (www.llgc.org.uk) also hold mining union records. Here are some of the main specialist libraries and archives, but you will need to make an appointment prior to any visit.

• National Union of Mineworkers, 2 Huddersfield Road, Barnsley, S70 2LS [t] 01226 284006; [w] www.num.org.uk. The NUM/MFGB records are not properly catalogued as yet, though there have been discussions about the establishment of a new research centre.

• The Modern Records Centre (MRC), University Library, University of Warwick, Coventry, CV4 7AL [t] 024 7652 4219; [e] archives@warwick.ac.uk [w] www2.warwick.ac.uk/services/library/mrc). A major trade union records repository including the archives of the TUC. The Centre has a useful online Family History and Occupational guide. Online catalogue. Holdings include records of the National Association of Colliery Overmen, Deputies & Shotfirers (NACODS) (ref: ODS), from 1962; publications relating to the the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain (MFGB) and National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) 1888–1992 (ref MFG) including some constituent MFGB associations; and the NUM Birch Coppice (Warwicks) Branch 1941–68 (ref NUM). There are also online guides on the General Strike (1926) and Miners’ Strike (1984—5). Very useful is the current King Coal exhibition webpage (www2.warwick.ac.uk/services/library/mrc/images/coal) which ran alongside the British Film Institute’s ‘This Working Life’ project. This archive does not hold membership records, so you are unlikely to find a miner’s individual record, but it is an excellent source for background information.

• TUC Congress Library Collections, Holloway Road Learning Centre, 236–250 Holloway Road, London, N7 6PP. [t] 020 7133 3726; [e] tuclib@londonmet.ac.uk; [w] www.londonmet.ac.uk/services/saslibrary-services/tuc/. A massive source for pamphlets and periodicals especially. Online catalogue and Enquiry Desk.

• Working Class Movement Library, Jubilee House, 51 The Crescent, Salford, M5 4WX [t] 0161 7363601; [e] enquiries@wcml.org.uk www.wcml.org.uk; [w] www.wcml.org.uk. Started in the 1950s by union activists Edmund and Ruth Frow. Houses a wonderful collection of books, leaflets, recordings, memorabilia etc. The website has genealogical advice/guidelines. Online catalogue of library and archives includes NUM/MFGB records. A really good place for background information.

• People’s History Museum, Left Bank, Spinningfields, Manchester, MR3 3ER. [t] 0161 838 9190; [e] info@phm.org.uk; [w] www.phm.org.uk. Ex National Museum of Labour History, reopened in February 2010 after a massive redevelopment. Objects of regional and national importance (online catalogue) include banners and badges; also commemorative items, posters, photographs, pamphlets, tokens and medals. The Labour History Archive and Study Centre (LHASC) (online catalogue) complements the objects, allowing access to resources on social, economic and political life. Jack Jones Reading Room for researchers, [e] archive@phm.org.uk.

2. Websites

• The Union Makes Us Strong (www.unionhistory.info). This is the important site based on the the TUC Congress Library Collections (London Metropolitan University). Free access to a massive amount of information and images.

• Trade Union Ancestors (www.unionancestors.co.uk). Mark Crail’s excellent site, well worth consulting, with friendly advice for family history research.

Further reading

Mark Crail, Tracing Your Labour Movement Ancestors (Pen & Sword Family History, 2009)

Robert (‘Robin’) Page Arnot’s four-volume histories of the MFGB and the formation of the NUM (1949–79) remain the most detailed general works, published by George Allen & Unwin: The Miners. A History of the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain 1889-1910 (1949); The Miners. Years of Struggle. A History of the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain from 1910 onwards (1953); The Miners in Crisis and War. A History of the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain from 1930 onwards (1961); The Miners. One Union, One Industry 1939–46 (1979)

Robert Page Arnot, A History of the Scottish Miners (George Allen & Unwin, 1955)

Robert Page Arnot, South Wales Miners. A History of the South Wales Miners’ Federation 1894–1914 (George Allen & Unwin, 1967)

Robert Page Arnot, South Wales Miners. A History of the South Wales Miners’ Federation 1914–1926 (Cymric Federation Press, 1975)

Carolyn Baylies, The History of the Yorkshire Miners 1881–1918 (Routledge, 1993)

Alan Campbell, The Lanarkshire Miners. A Social History of their Trade Unions, 1775–1974 (John Donald, 1979)

Alan Campbell, The Scottish Miners 1874–1939, Vol. 2, Trade Unions and Politics (Ashgate Publishing, 2000)

J. Davison, Northumberland Miners’ History 1919–1939 (NUM, 1973)

Hywel Francis and David Smith, The Fed. A History of the South Wales Miners in the Twentieth Century (Lawrence and Wishart, 1980)

Alan Ramsey Griffin, The Miners of Nottinghamshire 1914–1944. A History of the Nottinghamshire Miners’ Unions (George Allen & Unwin, 1962)

Frank Machin, The Yorkshire Miners. A History, (NUM, n.d. [c.1958])

Cliff Williams, A Pictorial History. National Union of Mineworkers Derbyshire Area 1880–1980 (NUM, 1980)

J.E. Williams, Derbyshire Miners. A Study in Industrial and Social History (George Allen & Unwin, 1962)

John Wilson, A History of the Durham Miners’ Association 1870–1904 (J.H. Veitch, 1907)

Strikes

V.L. Allen, The Militancy of British Miners (The Moor Press, 1981)

R. Church, and Q. Outram, Strikes & solidarity: coalfield conflict in Britain 1889–1966 (Cambridge UP, 1998)

David Douglass, Strike, not the end of the story. Reflections on the major coal mining strikes in Britain (National Coal Mining Museum for England Publications, 2005)

Francis Beckett and David Hencke, Marching to the Fault Line (Constable, 2009)

Brian Elliott (ed), The Miners’ Strike Day by Day. The illustrated diary of Yorkshire miner Arthur Wakefield (Wharncliffe Books, 2002)

Triona Holden, Queen Coal: Women of the miners’ strike (Sutton Publishing, 2005)

Banners

Derek Gillum, Banners of Pride. Memories of the Durham miners’ gala (Summerhill Books, 2009)

N. Emery, Banners of the Durham Coalfield (Sutton, 1998)

John Gorman, Banner Bright. An illustrated history of trade union banners (Scorpion, 1973 & 1986)

W.A. Moyes, The Banner Book. A study of the lodges of Durham Miners’ Association (Frank Graham, 1974)