CHAPTER 14

Language, Alphabet, and Linguistic Affiliation

Rex E. Wallace

1. The Etruscan Language

Introduction

The word “Etruscan” is used to refer to the language spoken and written by the inhabitants of Etruria in the period before Roman expansion. It was spoken and written also by Etruscans who settled in the Po Valley, in Latium, and in Campania, and by Etruscans who were engaged in commercial endeavors at emporia scattered throughout the Mediterranean.

Texts – all but one in the form of inscriptions – are identified as Etruscan by their linguistic characteristics, that is to say, by features of noun and verb morphology, by the phonological composition of the word-forms, and to a lesser extent by features of orthography and alphabet (see Sections 3 and 4 below). Even so, the classification of texts as Etruscan is not always clear-cut and the assignment of some to the Etruscan corpus is controversial (Cassio 1994; Watkins 1995: 42–45).

The oldest text in the Etruscan language, the inscription on the so-called Jucker vase from Tarquinia (Ta 3.1)1 dates to c.700 BCE. It is reasonable to assume, however, that the inhabitants of Villanovan sites in Iron Age Etruria spoke a prehistoric form of the language, and that the inhabitants of sites in Middle and Late Bronze Age Etruria did too. Claims of an eastern origin for the Etruscan language, though popular today, remain unsubstantiated (see text 7.18 below).

Etruscan texts span a chronological bridge of 700 years and two phases of linguistic development. Old Etruscan refers to texts dated to between 700 and 450 BCE, while Recent Etruscan refers to texts dated after the mid-fifth century. A sound change that deleted vowels in medial syllables, the so-called vowel syncope, serves as the line of demarcation. The latest texts in the corpus are the bilingual epitaphs from Chiusi and Perugia in Etruria (Cl 1.1221, Pe 1.211, Pe 1.313), and from Pisaurum in Umbria (Um 1.7). They belong to the final quarter of the first century BCE.

Literacy

Discussion of literacy in the Etruscan world amounts to little more than informed speculation. As will be seen in section 4, the Etruscan texts that have survived are inscriptions on durable material, and they belong to a limited set of common epigraphic types, e.g., funerary, votive, dedicatory inscriptions, etc. More important, this evidence was recovered in large part from burials, not from domestic contexts, public spaces, or workshops. As a result the evidence does not provide us with the full range of documentary material that must have been written by Etruscans. Texts written on perishable material did not survive. But despite the nature of the evidence, we have no reason to think that the Etruscans used writing for purposes that were substantially different than other Italic peoples, including the Romans.

It is tempting to speculate about who could read and write and at what level, but, once again, the evidence does it permit us to reach any meaningful conclusions about the percentage of the population that was literate or how far down the social ladder literacy reached at any period of Etruscan history. However, if we adopt a conservative approach and suppose that the spread of reading and writing in Etruria followed a trajectory similar to that proposed by Harris (1989) for Rome, we would calculate that a low percentage of the population – beginning with members of the elite classes – would have been literate in any meaningful sense of the word, even at the end of the Etruscan period.

Language Death

The Etruscan language died because its speakers shifted to Latin as their primary, and eventually only, means of communication. Etruscans chose to abandon their native tongue as a consequence of losing their political and military autonomy. But there were incentives to speak Latin too. Fluency in Latin provided them with the means to access the economic and social networks necessary for accommodation and advancement in the Roman polity.

The death of Etruscan was a gradual process; it was characterized by a period of time covering the third to first centuries BCE during which the social contexts in which the language was spoken became more and more restricted. Although the language became extinct, the Etruscans as a people did not.

2. The Origins of the Alphabet in Italy

The Greek Alphabet in Italy

Euboean Greek colonists from the towns of Eretria and Khalkhis introduced writing to the inhabitants of Italy. These colonists settled at Pithekoussai, and then a few decades later founded the town of Cumae on the mainland. Inscriptions recovered from these settlements, which date to the full eighth century BCE, reveal a vibrant immigrant community, some of whose members were not only literate but were well-schooled in Greek poetic culture (Bartoněk and Büchner 1995; Watkins 1995: 41–5).

An inscribed flask discovered in the tomb of a woman buried at Gabii, a settlement in northeastern Latium, is the earliest evidence of alphabetic writing in Italy. The flask dates to c.770 BCE (Holloway 1994: 112). If the writing is Greek, as many claim it to be, it is the earliest document in the Greek alphabet anywhere in the western Mediterranean (Watkins 1995: 36–39).

The Etruscan Alphabet

Etruscans who engaged Euboean Greek colonists, and became conversant in Greek and in Greek writing, were responsible for adopting and then adapting the alphabet to write Etruscan. Two orthographic innovations distinguish Etruscan writing from Greek. The first innovation is the spelling of the sound /k/ as >c<, >k< or >q<, depending on the following vowel letter.2 The Etruscan u-participle kacriqu /kakriku/ illustrates this orthographic practice. The second innovation is the spelling of /f/. This sound is not found in ancient Greek and so Etruscan scribes had to devise a spelling for it. They decided upon a combination of two letters, >v< and >h<; either order, >vh< or >hv<, was acceptable. The word θavhna “cup” /tʰafna/ and the name θihv&c.dotbl;aries “Thifarie” /tʰifaries/ illustrate the spelling. These innovations guarantee that the alphabet was borrowed and modified to write Etruscan no later than the end of the eighth century BCE. After the alphabet was adopted, it spread rapidly throughout Etruscan communities in Etruria and beyond.

The Etruscan Alphabet as a Source for Other “Italic” Alphabets

Etruscans served as a conduit for the spread of the alphabet to non-Etruscan speakers. Contacts with Italic-speaking settlements along the Tiber were strong during the eighth and seventh centuries BCE and as a result, the alphabet fanned out along these corridors of communication. Umbrians, Faliscans, Latins, and Sabines adopted the alphabet soon after it appeared in Etruria. Etruscans also carried the alphabet beyond the Arno and the Apennines. Tribes inhabiting the Po valley and the sub-alpine regions of Italy were writing as early as the sixth century BCE. Inscriptions in Cisalpine Celtic, Venetic and Raetic, all written in Etruscan-based alphabets, confirm the central role of the Etruscans in the spread of the alphabet outside of Etruria.

3. Etruscan Alphabets and Orthography

Alphabetic Reform and Regional Etruscan Alphabets

Early adopters of the alphabet lived in the southern Etruscan towns of Caere, Veii, and Tarquinia. The alphabet spread from these sites in a northerly direction via elite corridors of communication and commerce. Once members of a community adopted the art of writing, they were free to alter the inherited shapes of letters and to change orthographic practices to suit their own tastes. Regional differences in writing developed in Etruria soon after the alphabet spread.

By the sixth century BCE, three areas of orthographic diversity had developed in Etruria – roughly, southern, central and northern Etruria. It was based on two orthographic features: (1) the spelling of the sibilant consonants, /s/ and /ʃ/, and (2) the spelling of the voiceless velar stop, /k/. In the southern Etruscan communities of Caere and Veii, scribes settled on the letter gamma >c< to spell the sound /k/; kappa >k< and qoppa >q< fell from use. The same orthographic practice was adopted in central Etruria. In northern Etruria, scribes preferred the letter kappa >k< to spell /k/; gamma and qoppa became moribund. The spelling of the sibilants was more complex, as Table 14.1 illustrates.

Table 14.1 Regional Spelling of the Sibilants (/s/ and /ʃ/) and the Velar Stop (/k/).

| Regions | /s/ | /ʃ/ | /k/ |

| Northern (Chiusi) | |||

| Central (Tarquinia) | |||

| Southern (Caere and Veii) |

At Caere and Veii, the dental sibilant /s/ was represented by three-bar sigma >s< and the palatal sibilant /ʃ/ by four-bar sigma >ς&c.acute;<.3 In central Etruria, a three-bar sigma spelled the dental /s/, but the letter san >σ&c.acute;< was used for the palatal /ʃ/ sound. In northern Etruria, the spelling was reversed. San >σ< spelled /s/ and sigma >ś< spelled /ʃ/. This diversity of spelling had its origin in the graphic over-differentiation of the spelling of /k/ (too many letters to write one sound) and the graphic under-differentiation of the spelling of the sibilants (one letter to spell two sounds). In the first case, the complex system whereby /k/ was originally spelled by three letters, >c<, >k<, or >q<, was simplified. In the second case, a graphic distinction was created region by region in order to express a phonological distinction between the sibilants in the sound system.

The alphabet borrowed from Euboean Greeks had 26 letters, and its various manifestations are listed in Table 14.2.

Table 14.2 Etruscan Alphabets.

| Alphabet 1: seventh century BCE (AT 9.1) | a b c d e v z h θ i k l m n ŝ o p σ q r s t u  ϕ χ ϕ χ |

| Alphabet 2: sixth century BCE (Ta 9.1) | a [c e v z] h θ i k l m n [p σ q r s] t u ϕ χ |

| Alphabet 3: sixth century BCE (Ru 9.1) | a c e v z h θ i k l m n p σ q r s t u ϕ χ f |

| Alphabet 4a: third century BCE (AH 9.1) | a c e v z h θ i l m n p σ r s t u ϕ χ f |

| Alphabet 4b: 550–500 BCE (Pe 9.1) | a e v z h θ i l k m n p σ r s t u ϕ χ f |

These data indicate that the oldest Etruscan alphabets preserved all of the letters inherited from the Greek, even though the letters beta, delta, samekh (transcribed here as ŝ and omicron were never used to write Etruscan texts (Alphabet 1). A century later, alphabetic reforms eliminated unused letters from the series (Alphabet 2). At roughly the same time, a new letter, standing for the sound /f/, was added to the end of the series (Alphabet 3). By 500 BCE, the number of letters had been further reduced to 20 by eliminating either kappa and qoppa (Alphabet 4a; southern and central Etruria) or gamma and qoppa (Alphabet 4b; northern Etruria).

Retrograde >e< at Cortona

Changes in the pronunciation of diphthongs in Recent Etruscan created new sounds that were not distinguished in writing. For example, the diphthong /aj/, originally spelled >ai<, changed to a simple vowel, a phonetically long [eː], before the approximant /w/. Most Etruscan scribes spelled the “new” vowel by making use of the existing letter >e<. At Cortona, however, a clever scribe distinguished this vowel sound from the original e-vowel in the sound system by reversing the direction of the vowel letter >e< (retrograde >e< is transcribed as ê). By doing so, he introduced a “new” letter into the writing system (Agostiniani and Nicosia 2000: 47–52).

Punctuation

The oldest Etruscan inscriptions were written scriptio continua without any division between the words, and this style of writing survived in Recent Etruscan. Punctuation in the form of two or three vertically-aligned points separating words appeared in the seventh century BCE, and remained an optional feature of writing until Etruscan ceased to be written. However, the most common form of word-punctuation, especially in Recent Etruscan, was a single point placed at mid-line level.

Occasionally, different forms of punctuation were used within the same inscription for functions other than separating words, for example, to mark the end of a clause (AT 1.105) or an inscription (Cr 2.131), or to frame the beginning and the end of an inscription (Pa 2.7).

The division of inscriptions into “pages,” “paragraphs” or sections is more rare, but noteworthy examples exist. The epitaph of the Claudii (Cr 5.2), written in the fourth century BCE, was divided into three sections, each separated from the preceding by a double horizontal line. Double horizontal lines also set off the ten major sections of the Tabula Capuana (II. TC), a mid-fifth century BCE incised terracotta tile found at Santa Maria Capua Vetere in Campania. Vertical lines, on the other hand, divided the columns of the Liber Linteus, a ritual calendar, into twelve “pages,” while blank spaces of two or three lines divided the text into sections. Editorial marks in the shape of a Z also set off sections of the Tabula Cortonensis (III AC = Co 8.3), a bronze tablet with writing on both sides, while the Cippus Perusinus (IV CP = Pe 8.4), a legal agreement between the Afuna and Velthina families of Perugia, was divided up into “paragraphs” by leaving a space at the end or the beginning of a line.

Another form of punctuation is found on inscriptions incised by scribes working at the sanctuary of Portonaccio at Veii. Letters beginning and ending orthographic syllables that did not have CV or CRV structure were marked with points (e.g., mama.r.ce.a.punie “Mamarce Apunie” Ve 3.5). This orthographic practice, which is known as syllabic punctuation, may have originated as a teaching or spelling aid in scribal schools (Pandolfini and Prosdocimi 1990).

Direction of Writing

Etruscan texts were written almost exclusively in a right-to-left direction. Deviation from this norm is found in Old Etruscan inscriptions recovered from Caere, Veii and environs, but this practice spans a relative short period of time, from c.650 to 575 BCE (see inscription 7 in Section 4). Recent Etruscan inscriptions, particularly those composed within second and first centuries BCE, sometimes adopted left-to-right direction of writing, in deference to the direction used to write Latin (e.g., Cl 1.196, Cl 1.254, Cl 1.421, Cl 1.487, etc.).

4. Etruscan Texts

Inscriptions

The Etruscan texts that have survived are, with a single exception to be discussed below, inscriptions – that is to say, texts incised, painted or stamped on objects made of durable material (ceramic, metal, and stone). They belong to epigraphic categories that are well attested throughout the ancient Mediterranean. The total number in the corpus is over 10,000 (Meiser 2014).

Sixty words purported to be of Etruscan origin are found in the works of classical authors – Varro, Suetonius, Strabo, and others – and in the Lexicon of the late-Greek grammarian Hesychius (fifth century CE). Unfortunately, the citations are not always trustworthy. Some words are Greek (δέα “goddess,” κάπρα “goat”). Words that are demonstrably Etruscan, such as the word for “god” (aesar, αἴσοι), are sometimes altered to conform to the morphological and phonological templates of Greek or Latin, thus depriving them of much of their utility for the study of Etruscan. But the citations have provided some gems too. The names of several months have proved to be important additions to the lexicon and have contributed to the analysis of sections of Etruscan ritual texts.

Funerary inscriptions make up a high percentage – over 60 percent – of Etruscan texts. They range in date from the seventh century to the first century BCE, with a majority belonging to the third–first centuries. As is to be expected, epitaphs have minimal linguistic structure, most often conveying the name of the deceased (see inscription 1) and his or her familial relations (see inscription 2). Inscriptions on the tomb facades of the Crocifisso del Tufo necropolis outside of Orvieto offer the syntax of proprietary texts (inscription 3) (Figure 14.1) (for the syntax, compare inscription 7 below).

Figure 14.1 Funerary inscription (mi aveles sipanas) on the architrave of a tomb, c.500 BCE.

From the necropolis of the Crocifisso del Tufo, Orvieto. Photo: R. Wallace.

- velθur tarχna[s] (Cr 1.42; 300–200 BCE)

“Velthur Tarkhnas”

- avle . tarχnas . larθal . clan (Cr 1.10; 250–225 BCE)

“Avle Tarkhnas, son of Larth”

- mi aviles sipanas (Vs 1.39; c.500 BCE)

“I (am the tomb) of Avile Sipanas.”

Funerary inscriptions from the Ager Tarquiniensis and from Vulci can be more expansive. They may include detail about the deceased’s lineage, his age, and the public and religious offices to which he was appointed, as noted in inscriptions 4–5.

- [al] ẹθnas : arnθ : larisal : zilaθ : ṭạṛχnalθi : aṃce (AT 1.100; 300–100 BCE)

“Arnth Alethnas, (son) of Laris, was magistrate in Tarkhna.”

- tute : larθ : anc : farθnaχe : tute : arnθals | haθlials . ravnθu : zilχnu : cezpz :

purtσ&c.acute;vana : θunz | lupu : avils : esals: cezpalχals (Vc 1.93; 250–200 BCE)

“Larth Tute, who was generated by Arnth Tute and Ravnthu Hathli, held the

magistracy seven (?) times, the purtshvana once. He died at the age of 72.”

A few examples commemorate the construction of tombs or their renovation. The most famous was incised on a column in the central chamber of the tomb of the Claudii at Caere (inscription 6).

- laris . av|le . laris|al . clenar | sval . cn . ϛ&c.acute;uθi | ceriχunce | (Cr 5.2; 400–300 BCE)

apac . atic | saniϛ&c.acute;va . θui . cesu . | clavtieθurasi

“Laris (and) Avle, sons of Laris, built (had built) this tomb while living. Both father and mother, the saniϛ&c.acute;- (?), (were) laid to rest here. For members of the Clavtie family.”

Old Etruscan inscriptions of the seventh and sixth centuries BCE are proprietary (7), dedicatory (8), and votive (9) in content. They follow simple, formulaic syntactic patterns. Artisans’ signatures (see inscription 10), which were sometimes incised or painted on vases, are syntactically simple too. Nevertheless, a not inconsiderable number of inscriptions from this period defy classification and interpretation (e.g., Cr 0.1 and Cr 0.4).

- mi ςunθeruza ςpuriaς mlakaς (OA 2.75; 625–600 BCE)

“I (am) the small pyxis of the beautiful Spuria.”

- mini kaisie θannursianna

mulvannice (Cr 3.14; c.600 BCE)

mulvannice (Cr 3.14; c.600 BCE)“Kaisie Thannursiannas gave me (as a gift).”

- itun turuce venel atelinas tinas cliniiaras (Ta 3.2; sixth century BCE)

“Venel Atelinas dedicated this (vase) to the Dioskouroi.”

- mini zinace aranθ arunzina mlaχu mlacasi (Cr 6.2; 625–600 BCE)

“Aranth Arunzina made me, a beautiful (vase) for a noble (person).”

“Longer” Inscriptions

The Etruscan inscriptions cited above are all short, the case with most extant examples of Etruscan writing. In fact, the list of inscriptions with more than 50 words has seven entries. The two Etruscan Pyrgi Tablets (Figure 14.2), which have 36 words and 15 words respectively, may be added to this list (see inscription 16).

Figure 14.2 Tablet I with inscription in Etruscan, c.500 BCE. Gold.

From Pyrgi. Rome, Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia, inv. no. Provv.PS.S.S1. Photo: Universal Images Group/Art Resource, NY.

The longest document in Etruscan does not, in a technical sense, count as an inscription. The Liber Linteus is a manuscript written in ink on a sheet of linen. The text was written in 12 columns, which were divided into “pages” by means of vertical lines. Each column had 34 lines of writing, yielding a total of 1350 word-forms. If words that are repeated and inflectional forms of the same word are not counted multiple times, the total is reduced by about two-thirds.

The Liber Linteus functioned as a ritual calendar. Sacrifices to be made and prayers to be offered to Etruscan divinities are organized by month and day. For example, the sacrifice to Nethuns begins as follows:

- celi . huθiσ . zaθrumiσ . flerχva . neθunσl . σucri . θezeric (I. LL VIII, 3–4)

“On September twenty six, victims must be offered (?) and sacrificed (?) to Nethuns.”

This linen book survived by sheer luck. After the text was copied, probably in the third century BCE, Etruscans who migrated to Egypt to escape Rome’s military reach carried the book with them. At some point – we do not know when – the book fell into disuse and was acquired by an Egyptian family who cut it into strips and used it to wrap the corpse of a deceased woman.

The Tabula Capuana was incised on a terracotta tile; it was found at Santa Maria Capua Vetere in Campania and dates to the middle of the fifth century BCE. The bottom of the tile is so badly damaged that the words in the central portion of the text field are not legible. 62 lines of text, divided into ten “chapters,” survive. The word-count is 390, but the total number of words, allowing again for repeats and inflectional forms of the same word, is around 200. The Tabula Capuana, as the excerpt in inscription 12 illustrates, is also a ritual calendar and is structured like that of the Liber Linteus (12).

- isveitule ilucve apirise leθamsul ilucu cuiesχu perpri (II. TC II, 8)

“On the festival of the Ides, in April, the cuieskhu rite of Lethums must be performed (?).”

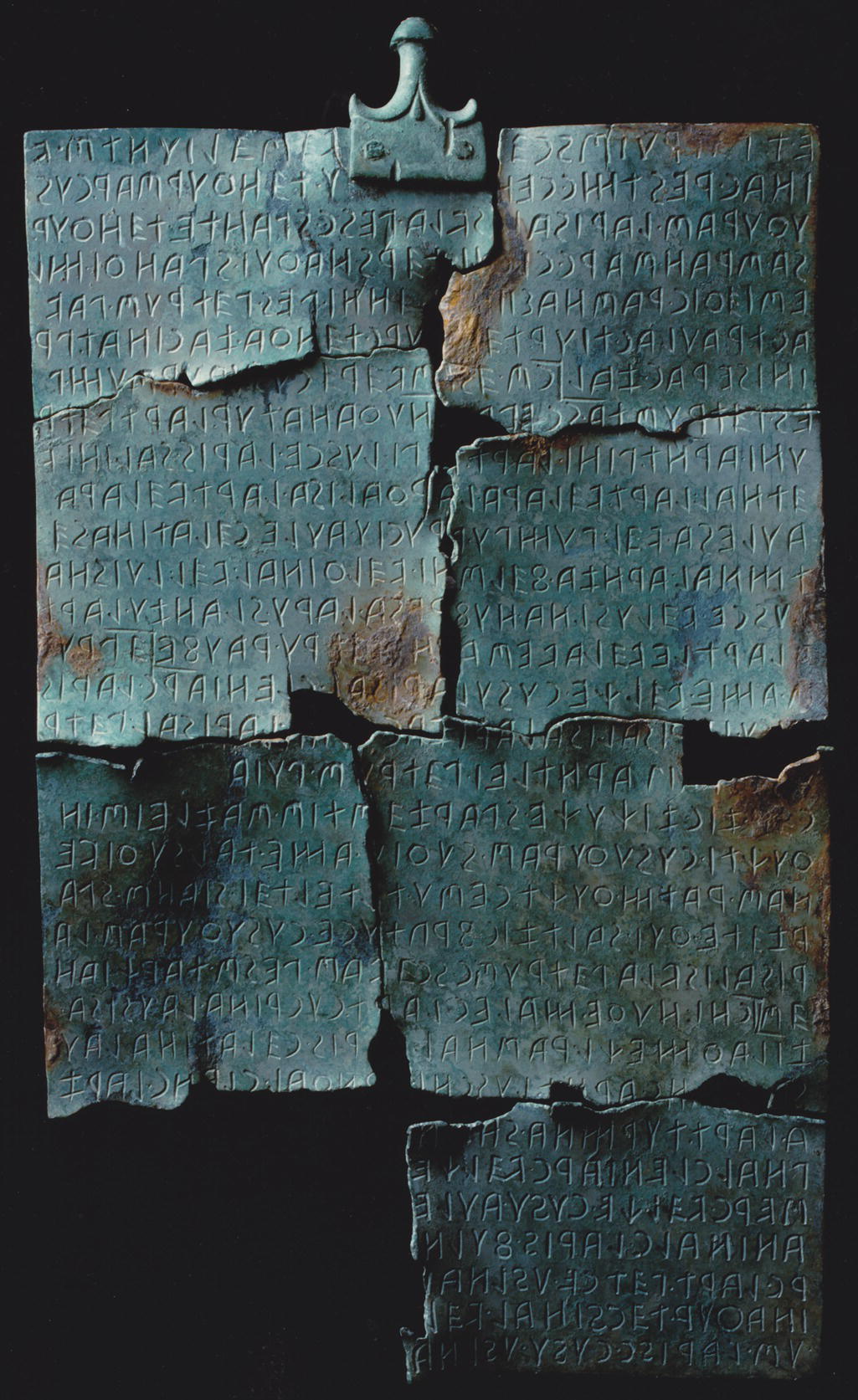

In 1992 a bronze tablet with writing on both sides, now known as the Tabula Cortonensis, was turned over to authorities in Cortona (Figure 14.3). The inscription, which was published in 2000, generated considerable excitement because of its length and content. The text is 40 lines long, with 32 lines of writing on Side A and 8 on Side B. There are 206 word-forms. The text is a legal agreement between Petru Shceva and members of the Cushu family over the return of land. The text begins with the following statement:

Figure 14.3 The Cortona Tablet (Tabula Cortonensis), c.250–200 BCE. Bronze.

From Cortona. Cortona, Museo dell’Accademia Etrusca e della Città di Cortona. Photo: © Luciano Agostiniani.

- e{.}t . pêtruiσ ścêvêσ êliuntσ . v|inac . restmc . ceṇ(vacat)u . tênθur σar . cuś|uθuraσ (III. AC, 1 = Co 8.3)

“Thus both the vina and the restm (were) ceded (?) by Petru Shceva, the eliun, in the amount of 10 acres (?) to the Cushu family.”

The Cippus Perusinus, the fourth longest Etruscan text, is also a legal agreement. It is a copy of a contract between the Afuna and Velthina families of Perugia over property rights. 24 lines of text were incised on the front of a stone cippus; another 22 lines appear on one of the sides. The total number of word-forms is 128.

- auleσi . velθinaσ arznal cl|enσi . θii . θil σcuna . cenu . e|plc . felic larθalσ afuneσ (IV. CP a, 9–11 = Pe 8.4)

“As regards the water, the rights (?) to water (were) granted by Larth Afuna, both epl and feli, to Aule Velthina, the son of Arznei.”

The Santa Marinella inscription (Cr 4.10) is a bronze plaque with writing on both sides. Two non-fitting fragments of the bronze survive, both badly damaged. 40 words and parts of another 40 survive. The plaque, which dates to the fifth century BCE, was found in the sanctuary of Punta della Vipera.

The lead tablet of Magliano (Av 4.1) too is an opistograph. It is oval in shape; words were incised in a spiral from the outer edge running in toward the center. The tablet was incised about 450 BCE. It is a religious text of some sort to judge from the mention of Cautha and other divinities.

The image of Laris Pulenas holding a book scroll in his hands was sculpted on the cover of his sarcophagus. His epitaph was incised on the scroll. The sarcophagus and text date to the first half of the second century BCE. The inscription thus has the distinction of being the most recent Etruscan text of any length. It records the genealogy of Pulenas as well as his political and religious activities. The initial sentences read as follows:

- l(a)ṛis . pulenas . larces . clan . larθal . papacs | velθurus . nefts. pruṃs. pulẹ&c.acute;ṣ . larisal. creices | an cn . zịχ . nẹ&c.acute;θśrac&c.dotbl; . acasce . (Ta 1.17, 1–3)

“Laris Pulenas, son of Larce, grandson (?) of Larth, great-grandson (?) of Velthur, descendent (?) of Laris Pule Creice (‘the Greek’). He put together (?) the document on haruspicy.”

Three inscribed gold plaques were recovered in 1964 during excavation of the Etruscan sanctuary at Pyrgi. Two plaques (Figure 14.2) were inscribed in Etruscan, the third in Phoenician. The latter, although not a translation of the Etruscan, provides a guide for interpretation. The plaques describe the dedication of a cult building to the divinity Uni (Phoenician Astarte) by Thefarie Velianas, the king of Caere. The first sentence of plaque one is cited in (16).

- ịta tmia icac he|ramaśva vatieχe | unialastrẹs (Cr 4.4; c.500 BCE)

“This shrine and this sanctuary were requested (?) by Uni.”

5. Language

Morphological Classification

Etruscan is classified as an agglutinating language in the manner of Turkish and Hungarian. Etruscan nouns best illustrate this type of morphological structure. Inflectional suffixes generally represent a single meaning or grammatical feature. For example, Etruscan aiseraσ (gods) had three constituents: a stem aise- “god,” a plural suffix -ra, and an genitive ending –σ.

Morphology

Nominal forms in Etruscan appear as a morphologically simple root, e.g., clan “son,” seχ “daughter,” ais “god,” ziχ “document, writing, book,” θi “liquid, water,” sren “image,” or as a morphologically complex stem, e.g., σ&c.acute;uθ-i “resting place, tomb,” θi-na “jar (for liquid).” The inventory of noun and adjective forming suffixes is not understood in all respects, but the form and function of those cited in Table 14.3 are secure.

Table 14.3 Noun and Adjective Suffixes.

| Suffix | Uses | Examples |

| -za |

forms nouns indicating diminutive size forms diminutives of names |

leχθumuza “small oil flask” larza “Larth junior” |

| -θur (-tur) | forms nouns indicating membership |

clavtieθur “members of Clavtie family” nuθanatur “a group of witnesses” |

| -c | forms adjectives from nouns |

zamθic “of gold” nẹθσ&c.acute;rac&c.dotbl; “of a haruspex” |

| -aθ | forms agent nouns from noun and verb stems | zilaθ “one who governs” |

| -na | forms adjectives from noun stems, including family names | σ&c.acute;uθi-na “of the tomb” apa-na “of the father” larice-na “the Laricena family” |

Nouns inflected for number and case. There were two numbers (singular and plural), and four oblique cases (genitive, pertinentive, ablative, and locative). The uninflected form of the noun, referred to here as the nominative / accusative form, served as the base of the paradigm. The suffix of the locative was -i. The remaining oblique cases had two sets of inflectional suffixes (informally called endings): s-endings and l-endings. The s-endings were the following: genitive -s /s/, pertinentive -si /si/ and ablative *-is (the vowel -i of the ending combined with the stem-final vowel). The l-endings were: genitive -al (Old Etruscan -a), pertinentive -ale, and ablative -als (Old Etruscan -alas). Representative forms are cited in Table 14.4.

Table 14.4 Case Forms of Nouns and Adjectives.

| Case forms | Examples |

| nominative/accusative |

śpura “community” zilχ “magistracy” meθlum “city” clan “son” avil “year” mlaχ “good” tmia “shrine” |

| genitive |

σpural “community” clens “sons” meθlumeσ “city” avils “year” mlakas “good” larθal “Larth” zilacal “magistracy” tmial “shrine” |

| pertinentive |

clensi “son” mlacasi “good” larθale “Larth” |

| ablative |

śpures < *śpurais “community” śparzeσ < *śparzaiσ “tablet” meθlumeσ < * meθlumeiσ “city” larθals “Larth” |

| locative |

zilci “magistracy” meθlume < *meθlumei “city” θii “water” zati < *zatii “club” |

The inflection of a noun in the singular, that is to say, whether it took the s-endings or the l-endings, was not predictable based on the nominative/accusative stem (but see Section 5: The Onomastic System). A few nouns could be inflected with both types of endings without any difference in meaning. Consider, for example, the genitives cilθσ “fortress (?)” and cilθl. Why this should be the case is not clear.

Nouns belonged to one of two semantically determined classes. The semantic feature [± human] distinguished the two (Agostiniani 1992: 54–55). Thus, clan “son” belonged to the [+ human] class, while avil “year” belonged to the [− human] class. The two classes were distinguished formally in terms of their inflectional endings. Nouns classified as [+ human] formed their plural with an r-suffix (Table 14.5, Section A); nouns that were [− human] formed their plural with the suffix -χva and its variants -cva and -va (Table 14.5, Section B).

Table 14.5 Etruscan Plurals.

| Singular | A. Plural formed with an r-suffix |

| clan “son” | clenar “sons” |

| ais “god” | aiser “gods” |

| papals “grandchild” | papalser “grandchildren” |

| B. Plural formed with the suffix -χva and its variants -cva and -va | |

| avil “year” | avilχva “years” |

| cilθ “fortress” | cilθcva “fortresses” |

| zusle “zusle-offering” | zusleva “zusle-offerings” |

The two classes were further distinguished by inflection and syntax. Nouns that inflected with the r-plural took the s-endings, while nouns that inflected with the χva-plural took the l-endings. When numbers modified nouns, the plural suffix was obligatory for nouns of the [+ human] class, but optional for nouns that were [- human] (e.g., ci clenar “three sons,” ki aiser “three divinities,” but ci zusle “three zusle-offerings,” cf. pl. zusleva).

Adjectives inflected for case, but no evidence has been adduced to show that they inflected for number, though one would expect that substantivized adjectives would take plural inflection under the appropriate syntactic conditions.

Etruscan had two demonstrative pronouns (ita/eta “this, that” and ica/eca “this, that”), an indefinite pronoun (ena “anyone, anything”), a determiner (-(i)σ&c.acute;a “the”), and two relative pronouns (an and in). The determiner, which was an enclitic, inflected like the demonstratives and almost certainly had demonstrative function in prehistoric Etruscan. The demonstratives ita and ica could be accented or unaccented. When unaccented, they were enclitic, and, in Recent Etruscan, were phonologically reduced in form (see Table 14.6).

Table 14.6 Etruscan Pronouns.

| Case |

Demonstrative pronouns (Old Etruscan Forms are on the left of the slash and Recent Etruscan forms on the right) |

First person pronouns | |

| nominative | ita/eta, ta | ica/eca, ca | mi |

| accusative | itan, etan, tn | ican, ecan, ecn, cn | mini, mine, mene |

| genitive | tas, tala/etas, tla | cas/ecs, cla | – |

Personal pronouns are attested for the first (mi) and third person (sa), and perhaps also for the second (un), but the identification of this form as a second pronoun is controversial (Rix 1991).

The inflection of pronouns differed from that of nouns and adjectives in several respects. Pronouns had an inflectional ending (-n, -ni) to mark the direct object of a verb. The pronominal l-genitive ending was -la, rather than -l. And finally, the pronominal genitive admitted both s- and l-suffixes without any functional distinction between the two. Partial inflectional paradigms of demonstratives and of the first person pronoun are given in Table 14.6.

The words for the numbers 1–6 are: θu(n), zal, ci, σ&c.acute;a, maχ and huθ. The words for 7–9 are cezp-, nurϕ- and semϕ-, but we are not sure which word matches up with which number. At this point the best guess is that cezp- is “seven,” semϕ- “eight,” and nurϕ- “nine.” The word “ten” is σar, and the word “twenty” is zaθrum. Multiples of 10 over 20 were formed by addition of -alχ to the numerical stem (e.g., ci-alχ “thirty,” śe-alχ “forty,” muv-alχ “fifty,” cezp-alχ, semϕalχ, and nurϕalχ “seventy” to “ninety”). The remaining numbers were compound formations. The first six numbers between 10 and its multiple were coordinate compounds, the second constituent being the word for 10 or its multiple (e.g., huθzar “sixteen,” ci zaθrum “twenty-three,” and maχs semϕalχls “eighty-five (?)”). The last three numbers between 10 and its multiple were formed by adding the suffix -em to the first constituent. Thus, the word “seventeen” was ciem zaθrms, which may be translated as “three subtracted from twenty.”

Multiplicative adverbs were formed from the stems of numbers by addition of the suffix -z, e.g., cezpz “seven times (?)” and citz “three times.”

Views of the Etruscan verb system – its forms and their constituent structures – as well as their meanings are more diverse than the views of the nominal system, but important areas of scholarly consensus exist (cf. Wylin 2000; Belfiore 2001; Rix 2004; Wallace 2008; Willi 2011). These are described below.

Etruscan verbs were inflected for tense, voice, and mood, but not for person and number. Past active verbs had the suffix -ce (e.g., Old Etruscan turuce “dedicated,” muluvanice “gave,” amake “was” and zinace “made”; Recent Etruscan turce; zince; lupuce “died” and amce). These forms contrast with verbs such as nuθe “observes,” male “sees,” ture “dedicates,” and ame “is,” which are unmarked for tense and so may cover functions ranging from present to future. Past passive verbs had the suffix -χe (e.g., Old Etruscan ziχuχe “was engraved, designed, written” and menaχe “was prepared (?)”). The verbs tenine “is held” and cerine “are constructed” are best construed as passives, as inscription 17 demonstrates; the verbs are unmarked for tense.

- eca : σ&c.acute;uθic : velus : ezpus | clensi : cerine (Vc 1.87; third century BCE)

“This (monument) and tomb (belong to) Vel Ezpus; they are constructed by his son.”

The uninflected verb root or stem served as the imperative (e.g., tur “dedicate,” σ&c.acute;uθ “put,” trin “speak” and nunθen “invoke”). The imperative capi “take, steal” is found in so-called anti-theft inscriptions (18).

- mi χuliχna cupe.s. .a.l.θ.r.nas .e.i minipi c&c.dotbl;api | mini θanu (Cm 2.13; fifth century BCE)

“I (am) the bowl of Cupe Althr&c.ringbl;na. Don’t steal me. Thanu (?) me.”

Modal forms of the verb ended in the suffixes -a and -ri. Verbs with the suffix -a had jussive function (e.g., inscriptions 19 and 20). Verbs ending in -ri referred to activities that were obligatory, as can be seen with the function of σucri, θezeri, and perpri in inscriptions 11 and 12 (above section 4).

- ein θui ara enan (Cl 0.23; fifth century BCE)

“No one should put/make (?) anything here.”

- raχθ tura heχsθ vinum (I. LL IV, 9)

“Let him place (?) (it) on the altar (?) while pouring (?) wine.”

Verbs could be formed directly from verb roots, but they could also be made from nominal or participle stems by means of suffixation. The suffix -(v)ani- (Recent Etruscan -n), having causative or factitive function, is well-attested in Old Etruscan (e.g., mulu-vani-ce “gave as a gift” and ziχ-(v)ani-ce “composed a document about”). Recent Etruscan verbs such as zilaχnuce “held a magistracy” were also derived from nominal stems by means of an n-suffix; but in this case, the meaning was not factitive.

The Etruscan verb system also included participles derived from verb roots and verb stems. The most common formation was made by adding -u to roots (e.g., mul-u “given as a gift; gift” or lup-u “dead”) or past tense stems (e.g., aliq-u “given (?)”), without their being, as far as can be determined, any functional difference between the two formations. Participles in -θ, formed to roots and stems, referred to activities that were contemporaneous with that of the main verb (e.g., trin-θ “speaking,” nunθen-θ “invoking,” and heχσ-θ “pouring (?)”). Other participles were more complex morphologically, their constituent structure being difficult to assess (e.g., acnanas “having produced (offspring)” and acnanasa, both from the root ac- “to make, produce;” svalθas “living,” from the root sval- “to be living;” and zilaχnθas “having held/holding a magistracy,” from the stem zilaχn(u)- “to hold a magistracy”).

Etruscan did not have prepositions, but, as is to be expected of an agglutinating language, it did have postpositions. The postposition -ri “on behalf of” was affixed to locative case forms (e.g., śpureri “on behalf of the community”). The postposition -θi “in, on” and its variants -θ, -ti and -te were also added to locative forms; they indicated location (e.g., hupnineθi “in the funerary niche”). When affixed to place names, this postposition governed the genitive case (e.g., tarχnalθi “at Tarkhna” (Van Heems 2006: 51–56)).

Morphosyntax and Syntax

The syntactic functions of the inflected forms of nouns, adjectives, and pronouns are well-established. The nominative/accusative form served as the subject of transitive and intransitive verbs, and as the object of transitive verbs. This form was also used to indicate duration of time (e.g., ci avil “for three years”). The genitive case indicated possession (see inscription 7) and other forms of nominal dependency, e.g., familial relationships (see inscription 2). It also marked the indirect object in votive dedications (e.g., inscription 9). The pertinentive case indicated the person to whom something was given or for whom an activity was performed (Agostiniani 2011). In passive constructions, it marked the agent of an action (see inscription 17). In some noun phrases, the pertinentive case functioned as a locative of a genitive (e.g., zilci Ceisiniesi v “in the magistracy, the (magistracy) of Vel Ceisinie,” or serturiesi “in the (workshop) of Serturie”). The ablative case was used to indicate origins (e.g., larθals “deriving from Larth”) or to designate a part of a whole (e.g., śin aiσer faσeiσ “take (?), O gods, (some) of the salsa (?)”), but it too could stand for the agent in a passive construction (see inscription 5). The locative indicated place where and time when, as well as the instrument, means or manner by which an activity was accomplished.

The default order of the major constituents in Etruscan sentences was S(ubject) O(bject) V(erb). Orders other than SOV involved the movement of constituents, typically to the front of the sentence, for reasons having to do with emphasis. The placement of the accusative case pronoun in first position is common in inscriptions of the “speaking text” variety. In these cases the focus is on the artifact, which “speaks” to the viewer (see inscriptions 8 and 10 in section 4).

SOV order is in keeping with the arrangement of other constituents in Etruscan sentences from a typological perspective (Agostiniani 1993). Genitive phrases, pronominal adjectives, and numbers tend to be placed before the nouns they “modify” (e.g., larθal clan “son of Larth,” ita tmia “this shrine,” ci avil “for three years”), while ad-positions follow the nouns they govern (e.g., śpureri = śpure + -ri “on behalf of the community”). Adjectives, insofar as can be determined, typically follow their nouns (see the noun phrases in inscriptions 7 and 12 in Section 4).

Adjectives agreed with their nouns in case. Demonstrative adjectives and the determiner did so as well. Evidence indicates that the determiner also agreed with its noun in number. An example is given below (inscription 21). In the noun phrase cuśuθuraσ lariśaliśvla, the word lariśaliśvla is parsed as lariśal-iśvla; -iśvla is the genitive plural of the article. It agrees with its noun cuśuθuraσ in case and number.

- śpa|rzête. θui. śalt. zic. fratuce. cuśuθuraσ . la|riśaliśvla . pêtruσc . ścêvaσ (III. AC, 18–19= Co 8.3)

“Here, on this tablet (?), (the Shians) incised the contract (?) of the Cushu brothers, the (sons) of Laris, and of Petru Shceva.”

Etruscan had two coordinate conjunctions, -ka/-ca/-c “and” and -um/-m “and, but.” The former coordinated phrases and clauses (see inscription 16). The latter did, too, but it could also have adversative function. Recent investigation suggests that it may have had discourse functions as well (Poccetti 2011). Both conjunctions were enclitic. Etruscan also permitted asyndetic coordination of noun and verb phrases (see inscription 6).

The selection of the relative pronoun depended on the semantic class of the antecedent (Agostiniani and Nicosia 2000: 100). If the antecedent phrase had the feature [+ human], the relative word was an (see inscription 5); if the antecedent phrase had the feature [- human], then the relative was in. In the sentence cited below (inscription 22), the relative pronoun in, which is the subject of the verb phrase śuθiu ame, refers back to the ablative phrase śparzêσtiσ σazleiσ.

- cên . zic . ziχuχe . śparzêσtiσ . σazleiσ . in | θuχti . cuśuθuraσ . śuθiu . ame (III. AC, 18–19 = Co 8.3,)

“This document was copied from the wooden (?) tablet (?) which is kept in the home (?) of the Cushu brothers.”

The syntax of subordinate sentences is not very well understood, although several subordinators have been identified: nac “when, after, since (?),” iχ “just as,” and iχnac “how” introduced adverbial clauses (see inscription 23), while ipa “that” introduced noun clauses (see inscription 24).

- eca : sren : | tva iχna|c hercle : | unial cl|an θra{:}σ&c.acute;ce (Vt S.2; fourth/third century BCE)

“This image shows (?) how Hercle became (?) the son of Uni.”

- eθ fanu lautn precuσ ipa murzua cerurum ein heczri (Pe 5.2, 2–3; second century BCE)

“Thus, the family Precu declared (?) that neither the urns nor the cerur (?) were to be emptied (of their contents) (?).”

Phonology

The Old Etruscan phonological inventory had 21 sounds: 17 consonants and 4 vowels. The consonants, as outlined in Table 14.7, may be represented schematically based on the features of place and manner of articulation.

Table 14.7 Etruscan Consonant System.

| Labials | Dentals | Palatals | Velars | Glottals | |

| Stops | p | t | k | ||

| pʰ | tʰ | kʰ | |||

| Fricatives | f | s | ʃ | h | |

| Affricate | tˢ | ||||

| Nasals | m | n | |||

| Liquid | l | ||||

| Rhotic | r | ||||

| Approximants | 𝒥 | w |

The consonant system had two series of voiceless stop sounds. The first series was un-aspirated /p, t, k/, the second, aspirated /pʰ, tʰ, kʰ/. There were four fricatives /f, s, ʃ, h/ and one affricate /tˢ/, all voiceless. The sonorant consonants consisted of two nasals /m/ and /n/; a lateral liquid /l/; a rhotic /r/; and the approximants /j/ and /w/. These sounds were voiced.

The Old Etruscan vowel system consisted of two front vowels, one high /i/ and one mid /e/; a low, back, un-round vowel /ɑ/; and a back round vowel /u/. In addition to these simple vowels, there were several diphthongs: /ɑj/, /ej/, and /ɑw/. The diphthongs /uj/ and /uw/ entered the system as a result of borrowing.

Etruscan also had a stress accent, which was placed on the vowel in the initial syllable of a word. Syllable-initial accent affected the quality of the vowels in successive syllables and led eventually to their loss. This happened in two stages. In Old Etruscan, medial vowels lost their distinctive quality, in all likelihood changing to a mid-central vowel [ə]. This accounts for the fluctuation in the spelling of medial vowels during the sixth and early fifth centuries, as can be seen if we compare the spellings of the personal name Avile: avile, avale, avule, and avele (all phonetically [awəle]). By the middle of the fifth century, [ə] was lost, sometimes leaving behind complex consonant clusters and causing inter-consonantal nasals, liquids and rhotics to assume vocalic function, e.g., avile > avle /ˈawle/ “Aule,” turuce > turce /ˈturke/ “dedicated,” ramuθa > ramθa /ˈramtʰa/ “Ramtha,” but menerva > menrva /ˈmenr&c.ringbl;wa/ “Menerva,” vestricin[as] > veśtrcnaσ /ˈweʃtr&c.ringbl;knas/ “Veshtr&c.ringbl;knas.”

Vocabulary

The inscriptions in the Etruscan corpus cover a limited range of topics. As a result, the vocabulary that has survived, and for which meanings can be determined, belongs to small number of semantic areas: religion, kinship, death and burials, political offices, months of the year, styles of pottery and so forth. Moreover, the meanings of a significant number of the vocabulary items in our inventory, which might provide us with a broader view of the Etruscan lexicon, cannot be determined from the inscriptions in which they are found. Thus, while we know the names of various types of vases, we do not know the words for everyday vocabulary, food items, types of furniture, styles of clothing, or personal relationships.

Native Etruscan words are well represented in the area of familial relationships. The words that have been identified are: clan “son,” seχ “daughter,” apa “father,” ati “mother,” ruva “brother,” papals and tetals “grandchild” on the father’s and mother’s side respectively, and puia “wife.” The words for “grandfather” and “grandmother” are compound formations: apa nacna and ati nacna.

The largest segment of Etruscan vocabulary, coming as it does from the Liber Linteus and the Tabula Capuana, is religious in nature. A selection of words from these sources includes: ais “god” (aiser pl.), farθan “genius, spirit,” faσe “salsa (?),” fler “offering (?),” flere “divine spirit,” zivas “living,” zusle “victim,” θezeri “must be sacrificed,” nunθen “invoke,” raχ “altar (?),” sacnica “brotherhood (?),” śuθ “place, put,” trin “speak,” and turza “[small] offering.” The words vinum “wine” and cletram “carrier,” which figure prominently in offerings and ritual actions, are loanwords from Umbrian. But many words attested in these texts are hapax legomena: their meanings cannot be determined.

Several terms for ceramic objects come from ancient Greek: κώθων “drinking vessel” →qutum, λήκυθος “oil flask” → leχtum(uza), πρόχους “jug” → pruχum, and κυλίχνη “small cup” → χuliχna. The phrase aςka eleivana refers to an “askos for olive oil.” The adjective eleivana has, as its stem, the Greek word ἐλαίϝα. In inscription OA 3.15 elaivana (note the spelling difference) is used substantively; it refers to a flask for oil (mi m{:}laχ mlakas larθus elaivana “I (am) the beautiful oil flask of the noble Larthu.”). A few native formations are also attested. For example, Etruscan spanti (plate) is derived from span, the word for “plain, flatland.” θina “jar [for liquid]” is the native word for a container for liquid; it is derived from θi, the word for “water” or “liquid.”

The Onomastic System

Etruscan shared with its Italic neighbors in central Italy an onomastic system that had the family name (gentilicium) as its fundamental unit. The family name was inherited by freeborn offspring from their father at birth. The personal name (praenomen) was the given name. In Old Etruscan, there were a rather large number of personal names, but those in common use steadily decreased over time. In Recent Etruscan no more than a dozen personal names were in common use (e.g., avle, phonologically /aule/, arnθ, vel, velθur, larθ, laris, marce, σ&c.acute;eθre, for men; velia, θana / θania, θanχvil, larθi, ramθa, σ&c.acute;eθra, and fasti/fastia for women). In addition to the personal name and the family name, the basic onomastic phrase in funerary inscriptions often included the patronymic, which was the father’s personal name inflected in the genitive case (see inscription 2 in Section 4).

Funerary inscriptions of the third and second centuries BCE, particularly those in the northern Etruscan towns of Chiusi and Perugia, expanded upon the basic onomastic phrase by including one or more of the following: a cognomen; a metronymic (the family name of the deceased’s mother); and a gamonymic (the family name of the deceased’s spouse). The cognomen, which served to distinguish branches within an extended family, was also inherited.

Inscriptions with four or five onomastic constituents are not uncommon at Chiusi. Inscriptions 25 and 26, both epitaphs, are examples.

- lθ : peθna : aθ : titial : ścire (Cl 1.147, c.300 BCE)

“Larth Pethna Shcire, (son) of Arnth (and) Titi”

- θana : peθnei | ściria : tutnaśa | ḥelial : σec (Cl 1.148, c.300 BCE)

“Thana Pethnei Shciria, the (wife) of Tutna, daughter of Heli”

The names of slaves and freed persons are also attested in epitaphs. In the case of slaves, the onomastic phrase consisted of the slave’s personal name, often Greek in origin, and the family name of her/his owner. The nouns lautni “freedman” and lautniθa “freedwoman” accompanied the names of freed slaves, as inscription 27 illustrates.

- apluni : cum|eres : lautni (Cl 1.121, second century BCE)

“Apollonius, freedman of Cumere”

The inflection of names was more regular than the inflection of nominal forms. The final sound of the stem determined whether the inflectional endings were of the s- or l-type. Stems ending in vowels were inflected by means of the s-endings. Stems in -l and -r took the s-endings too, but the ending was preceded by the vowel -u (e.g., genitive vel-us “of Vel”). Stems in dental consonants took the l-endings. Feminine family names, which had the suffix -i, also followed l-type inflection. Forms of names are cited in Table 14.8, with Old Etruscan names listed on the left of the backslash.

Table 14.8 Case Forms of Personal and Family Names.

| Case Forms | Personal Names | Family Names |

| nominative/accusative |

larice/larce

ramaθa/ramθa venel/vel |

nuzarnai |

| genitive |

larices/larces

ramaθas/ramθas venelus/velus larisa/larisal larθia/larθial |

nuzinaia |

| pertinentive |

laricesi

licinesi ramaθasi venelusi larisale larθiale |

|

| ablative |

ramθes (stem ramθa) arnθals |

veleθnalaς

tarnes (stem tarna) |

6. Linguistic Affiliation

Proto-Tyrrhenian

Etruscan is linguistically related to two sparsely attested languages. The first is Lemnian, the language of the pre-Greek inhabitants of the island of Lemnos in the north Aegean (Agostiniani 1986; de Simone 1986 and 2009). The second is Raetic, a language spoken in the sub-Alpine regions of eastern Italy (Rix 1998; Schumacher 2004).

The linguistic features shared by these three languages are found primarily in the domain of inflection, though a few cognate lexical items can be cited (e.g., Lemnian avis “year” and Etruscan avils (both genitive case); Lemnian σ&c.acute;ialχveis “forty” and Etruscan σ&c.acute;ealχls (both genitive case); Raetic zinake “dedicated (?)” and Etruscan zinace “made”). The linguistic relationship posited on the basis of morphological and lexical similarities compel us to view Etruscan, Lemnian and Raetic as descendants of a common parent language, which is referred to as Proto-Tyrrhenian (Penny 2009).

How the geographical distribution of these languages is to be explained is another, more perplexing, question, and one that has been − and still is − the subject of considerable debate. It is possible that prehistoric Etruscan and Raetic speakers moved west to their current locations from a “homeland” in the eastern Aegean, perhaps in the Early Bronze Age. This view corresponds to the Eastern Origins “theory” in its current form. Another possibility is that prehistoric Lemnian speakers moved eastward from a “homeland” in Italy. This theory corresponds most closely to the autochthonous view of Etruscan origins.

Both scenarios are plausible, but we cannot prove which one, if any, is right because they must be projected so far back in time. So, while the linguistic evidence makes it clear that Etruscan, Lemnian and Raetic belong to the same family of languages, it cannot provide insight into the question of the Etruscans’ origins.

7. Conclusion

Etruscan is a dead language, and yet the interpretation of its inscriptions and the description of its linguistic structure constitute a vibrant field of investigation. Each excavation season yields new epigraphic evidence that sheds light on old grammatical problems and creates new ones for our consideration. For example, the publication of inscription Cr 1.197 from the “Tomb of the Inscriptions” at Caere has reignited the debate about function of ipa as a subordinating conjunction (Facchetti 2009). And the publication of the inscribed bucchero kyathos from Santa Teresa di Gavorrano (Vn 3.2) initiated a study of the palatalization of /s/ in northern Etruscan dialects (Eichner 2012: 69–77). The investigation of the language, although it has not reached the sophistication of our study of the Indo-European languages of ancient Italy, is at a point where it must be regarded as a legitimate object of rigorous scientific inquiry.

REFERENCES

- Adiego, I.-X. 2005. “The Etruscan Tabula Cortonensis: A Tale of Two Tablets?” Die Sprache 45: 3–25.

- Agostiniani, L. 1986. “Sull’ etrusco del stele di Lemno e sul alcuni aspetti consonantismo etrusco.” Archivio Glottologico Italiano 71: 15–46.

- Agostiniani, L. 1992. “Contribution à l’étude de l’épigraphie et de la linguistique étrusques.” Lalies 11: 37–74.

- Agostiniani, L. 1993. “Considerazaione tipologica dell’etrusco.” Incontri linguistici 16: 23–44.

- Agostiniani, L. 1997. “Considerazioni linguistiche su alcuni aspetti della terminologia magistrale etrusca.” In R. Ambrosini, ed., 1–16.

- Agostiniani, L. 2011. “Pertinentivo.” Alessandria. Rivista di glottologia 5: 17–44.

- Agostiniani, L. and F. Nicosia. 2000. Tabula Cortonensis. Rome.

- Ambrosini, R., ed. 1997. Scribthair a ainm n-ogaim: Scritti in memoria di Enrico Campanile. Pisa.

- Bartoněk, A. and G. Büchner. 1995. “Die ältesten griechischen Inschriften von Pithekoussai (2. Hälfte des VIII. bis 1. Hälfte des VII Jhs.).” Die Sprache 37: 129–231.

- Belfiore, V. 2001. “Alcune osservazioni sul verbo etrusco.” Archivio Glottologico Italiano 86: 226–245.

- Bense, G., G. Meiser and E. Werner, eds. 2006. August Friedrich Pott; Beiträge der Halleschen Tagung anlässlich des zweihundertsten Geburtstages von August Friedrich Pott (1802–1887). Frankfurt am Main.

- Carratelli, G. P., ed. 1986. Rasenna: Storia e civiltà degli Etruschi. Milan.

- Cassio, A. C. 1991–93 [1994]. “La più antica iscrizione greca di Cuma.” Die Sprache 35: 187–207.

- Cristofani, M. 1978a. “L’alfabeto etrusco.” In A. L. Prodocimi, ed., 401–428.

- Cristofani, M. 1978b. “Rapporto sulla diffusione della scrittura nell’Italia antica.” Scrittura e civiltà 2: 5–33.

- De Simone, C. 1986. “La Stele di Lemnos.” In G. P. Carratelli, ed., 723–725.

- De Simone, C. 2009. “La nuova iscrizione tirrenica di Efestia.” Tripodes 11.1–58.

- Eichner, H. 2012. “Anmerkungen zum Etruskischen In Memoriam Helmut Rix.” Alessandria. Rivista di glottologia 5: 67–92.

- Facchetti, G. 2009. “Note etrusche (II).” Annali dell’Università degli Studi di Napoli “L'Orientale.” Rivista del Dipartimento Del mondo classico. Sezione Linguistica 31: 223–267.

- Gaultier, F. and D. Briquel, eds. 1997. Les étrusques, les plus religieux des hommes, Actes du Colloque international (Paris, 1992). Paris.

- Harris, W. V. 1989. Ancient Literacy. Cambridge.

- Holloway, R. R. 1994. The Archaeology of Early Rome and Latium. London and New York.

- Maggiani, A. 1990. “Alfabeti etruschi dell’ età ellenistica.” Annali della Fondazione per il Museo “Claudio Faina” [La scrittura nell’Italia antica: Relazioni e communicazioni nel Convegno del 1985 (Orvieto)] 4: 177–217.

- Meiser, G. 2006. “Zur Struktur des Neptunsrituals im etruskischen Liber Linteus (I).” In G. Bense, G. Meiser and E. Werner, eds., 113–124.

- Meiser, G., ed. 2014. Etruskische Texte. Editio minor. Hamburg.

- Pandolfini, M. and A. L. Prosdocimi. 1990. Alfabetari e insegnamento della scrittura in Etruria e Italia antica. Florence.

- Penny, J. 2009. “The Etruscan Language and its Italic Context.” In J. Swaddling and P. Perkins, eds., 88–94.

- Poccetti, P. 2011. “Strutture della coordinazione in etrusco.” Alessandria. Rivista di glottologia 5: 253–287.

- Prodocimi, A. L., ed. 1978. Popoli e civiltà dell’Italia antica: lingue e dialetti dell’Italia antica, vol 6. Rome.

- Rix, H. 1991. “Etrusco un, une, unu ‘te, tibi, vos’ e le preghiere dei rituali paralleli nel Liber Linteus.” Archeologia Classica 43: 665–691.

- Rix, H. 1997. “Les prières du liber linteus de Zagreb.” In F. Gaultier and D. Briquel, eds., 391–398.

- Rix, H. 1998. Rätisch und Etruskisch. Innsbruck.

- Rix, H. 2004. “Etruscan.” In R. Woodard, ed., 943–966.

- Schumacher, S. 2004. Die Rätischen Inschriften. Geschichte und heutiger Stand der Forschung. Innsbruck.

- Swaddling, J. and P. Perkins, eds. 2009. Etruscan by Definition: The Cultural, Regional and Personal Identity of the Etruscans. Papers in Honour of Sybille Haynes. London.

- Van Heems, G. 2006. “L’inscription de l’oenochoe de Montpellier. Un formulaire original.” Mélanges de l'École française de Rome 118: 41–61.

- Wallace, R. E. 2008. Zikh Rasna. A Manual of the Etruscan Language and Inscriptions. Ann Arbor.

- Watkins, C. 1995. “Greece in Italy outside Rome.” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 97: 35–50.

- Weiss, M. 2010. Language and Ritual in Sabellic Italy. The Ritual Complex of the Third and Fourth Tabulae Iguvinae. Leiden and Boston.

- Willi, A. 2011. “Revisiting the Etruscan Verb.” Alessandria. Rivista di glottologia 5: 365–384.

- Woodard, R., ed. 2004. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World’s Ancient Languages. Cambridge.

- Wylin, K. 2000. Il verbo etrusco: Ricerca morfosintattica delle forme usate in funzione verbale. Rome.

GUIDE TO FURTHER READING

Taken together, the articles of Cristofani 1978a and 1978b provide an illuminating introduction to the origins and development of the Etruscan alphabet and to the spread of literacy in the period before Roman expansion. The article by Maggiani 1990 is the most important study of Recent Etruscan alphabets and orthography. The introduction by Weiss 2010 (particularly pp. 3–9) provides a lucid discussion of the methodological issues that may be used to analyze and interpret ancient texts. The articles by Meiser 2006 and Rix 1997 are important because they illustrate how the method of parallel texts can be used to illuminate sections of “long” Etruscan inscriptions. Agostiniani 1997 provides an exemplary study of one area of the Etruscan vocabulary that is reasonably well-understood. Even so, he demonstrates that a more nuanced view is possible. Finally, Adiego 2005 offers a brilliant analysis of an important Etruscan inscription, a perfect marriage of linguistic and textual analysis.