3

THE HERO’S JOURNEY

Harry’s adventures take him through life, death, and resurrection.

The Harry Potter books are laid out according to a formula repeated in each story. This formula, used in stories from ancient epics to modern adventure novels, is known by many different names and has been attributed many different meanings.[18] As it is used in the Harry Potter books, the hero’s journey or monomyth formula is a repeated snapshot in every book of Rowling’s theme that love conquers death and that we will rise from the dead in a resurrection made possible by and in Christ.

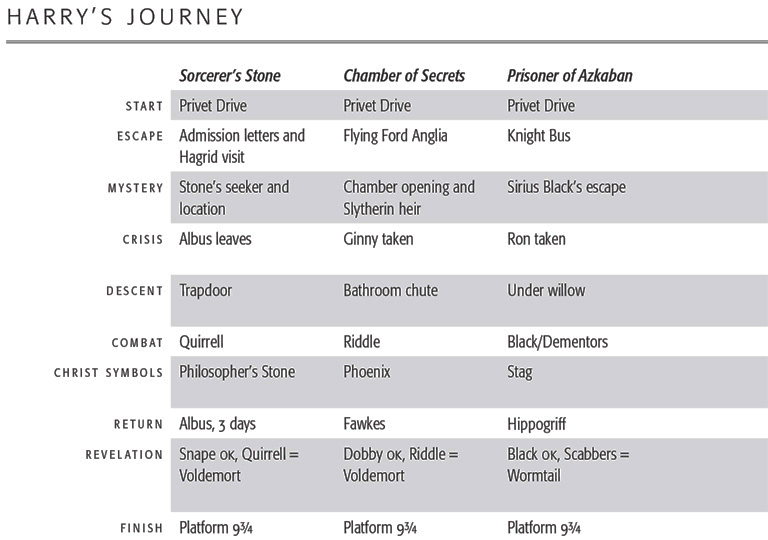

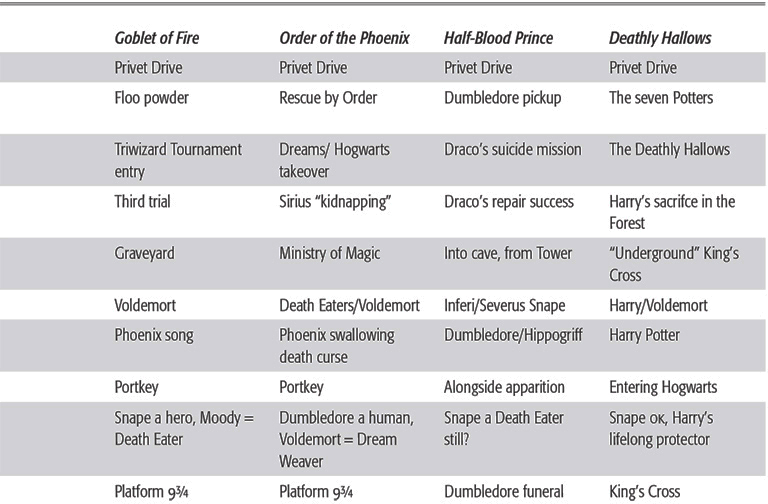

No doubt you find this hard to believe. Let’s start, then, just by describing the formula as shown in our second map and seeing what Harry’s journey involves. The first six books begin and end in the same place and pass a series of landmarks that differ only in details. Here is a rough chart of the pattern as it appears in each of the first six books:

Harry’s hero journey is a generic picture of each adventure Harry has taken.

He begins at home on Privet Drive with his Muggle family, the Dursleys.

He begins at home on Privet Drive with his Muggle family, the Dursleys. He escapes to Hogwarts from his living death via the intrusion of extraordinary magic (Hagrid’s birthday arrival, the flying Ford Anglia, etc.).

He escapes to Hogwarts from his living death via the intrusion of extraordinary magic (Hagrid’s birthday arrival, the flying Ford Anglia, etc.). Harry arrives at Hogwarts to find something mysterious going on.

Harry arrives at Hogwarts to find something mysterious going on. With help from Hermione and Ron, Harry tries to solve the mystery, which, inevitably, comes to a crisis demanding his immediate action (with or without his friends).

With help from Hermione and Ron, Harry tries to solve the mystery, which, inevitably, comes to a crisis demanding his immediate action (with or without his friends). He descends into the earth to face this crisis (except in Goblet of Fire, in which he portkeys to a graveyard, the surroundings of which have a resonant meaning with the underworld).

He descends into the earth to face this crisis (except in Goblet of Fire, in which he portkeys to a graveyard, the surroundings of which have a resonant meaning with the underworld). Harry fights Voldemort or a servant of the Dark Lord and triumphs against impossible odds (in books 3, 4, 5, and 6 merely by escaping alive).

Harry fights Voldemort or a servant of the Dark Lord and triumphs against impossible odds (in books 3, 4, 5, and 6 merely by escaping alive). He dies a figurative death, rises from the battlefield with the miraculous help of a Christ figure, and returns to the land of the living.

He dies a figurative death, rises from the battlefield with the miraculous help of a Christ figure, and returns to the land of the living. Harry learns from Professor Dumbledore that a good guy is really a bad guy and a bad guy is really a good guy (along with the meaning and lesson of his adventure).

Harry learns from Professor Dumbledore that a good guy is really a bad guy and a bad guy is really a good guy (along with the meaning and lesson of his adventure). Harry leaves us at Platform 9 ¾ to go home with the Dursleys.

Harry leaves us at Platform 9 ¾ to go home with the Dursleys.

Some friends have told me when I have shown them the second map that they feel cheated somehow. If this were just a mechanical formula, as in TV dramas, disappointment would be warranted. (Remember The A-Team television program? Same show every week with a different machine at the end to save the day?)

The Harry Potter formula, however, is anything but a scripting cookie cutter. While the story is a partial throwback to the heroes of old (Odysseus, Aeneas, Dante), these stories take quite a different turn. In the ancient and medieval epics, the heroes travel to the underworld to confront death (usually for information), entering and exiting without a trial much greater than the difficulties of the trip and the shock of what they see. Not so in Harry Potter.

Look at the chart again. What happens to Harry underground? Invariably he dies a figurative death.

In Philosopher’s Stone, Harry expires “[knowing] all was lost, and fell into blackness, down . . . down . . . down . . .” (chapter 17).

In Philosopher’s Stone, Harry expires “[knowing] all was lost, and fell into blackness, down . . . down . . . down . . .” (chapter 17). In Chamber of Secrets, Harry is poisoned by the basilisk. “Harry slid down the wall. He gripped the fang that was spreading poison through his body and wrenched it out of his arm. But he knew it was too late. . . . ‘You’re dead, Harry Potter,’ said Riddle’s voice above him” (chapter 17).

In Chamber of Secrets, Harry is poisoned by the basilisk. “Harry slid down the wall. He gripped the fang that was spreading poison through his body and wrenched it out of his arm. But he knew it was too late. . . . ‘You’re dead, Harry Potter,’ said Riddle’s voice above him” (chapter 17). In Prisoner of Azkaban, a Dementor lowers his hood to kiss Harry. “A pair of strong, clammy hands suddenly attached themselves around Harry’s neck. They were forcing his face upward. . . . He could feel its putrid breath. . . . His mother was screaming in his ears. . . . She was going to be the last thing he ever heard. . . . [When released, Harry] felt the last of his strength leave him, and his head hit the ground” (chapter 20).

In Prisoner of Azkaban, a Dementor lowers his hood to kiss Harry. “A pair of strong, clammy hands suddenly attached themselves around Harry’s neck. They were forcing his face upward. . . . He could feel its putrid breath. . . . His mother was screaming in his ears. . . . She was going to be the last thing he ever heard. . . . [When released, Harry] felt the last of his strength leave him, and his head hit the ground” (chapter 20). In Goblet of Fire, Rowling places Harry’s seemingly hopeless battle with the risen Voldemort in a graveyard, so Harry is not only in an almost certain collision course with death, he is also already among the dead (chapters 32–34).

In Goblet of Fire, Rowling places Harry’s seemingly hopeless battle with the risen Voldemort in a graveyard, so Harry is not only in an almost certain collision course with death, he is also already among the dead (chapters 32–34). In Order of the Phoenix, Harry is possessed by Voldemort to get Dumbledore to kill the boy. “And then Harry’s scar burst open. He knew he was dead: it was pain beyond imagining, pain past endurance” (chapter 36).

In Order of the Phoenix, Harry is possessed by Voldemort to get Dumbledore to kill the boy. “And then Harry’s scar burst open. He knew he was dead: it was pain beyond imagining, pain past endurance” (chapter 36). In Half-Blood Prince, the Inferi from the cavern lake grab Harry and begin to carry him into the Stygian depths. “He knew there would be no release, that he would be drowned, and become one more dead guardian of a fragment of Voldemort’s shattered soul” (chapter 26).

In Half-Blood Prince, the Inferi from the cavern lake grab Harry and begin to carry him into the Stygian depths. “He knew there would be no release, that he would be drowned, and become one more dead guardian of a fragment of Voldemort’s shattered soul” (chapter 26).

Not much to recommend the books, though, if the hero merely dies at crunch time, is there? Harry doesn’t just die in these stories, of course; he rises from the dead. And in case you think this is just a “great comeback” rather than a Resurrection reference, please note that Harry never saves himself but is always saved by a symbol of Christ or by love. As you can see from the chart, in Philosopher’s Stone, it is his mother’s sacrificial love and the Stone; in Chamber of Secrets, it is Fawkes the phoenix; in Prisoner of Azkaban, it is the white stag Patronus; in Goblet of Fire, it is the phoenix song; and in Order of the Phoenix, it is Harry’s love for Sirius, Ron, and Hermione that defeats the Dark Lord. Both Dumbledore and Buckbeak the hippogriff save Harry as Christ figures in Half-Blood Prince. That he rises after three days in Philosopher’s Stone is another obvious reference to the Resurrection.

Rowling begins her great departure from this formula at the end of the sixth book, Half-Blood Prince. At the end of that book Dumbledore is murdered, so there is no denouement with the headmaster and Harry does not return to King’s Cross or the Dursleys’. Harry vows that he will not be returning to Hogwarts for his seventh and final year of magical education because he has a mission to destroy Horcruxes and vanquish the Dark Lord.

Oddly enough though, even if Harry’s odyssey in Deathly Hallows does not conform to one or two details of Rowling’s monomyth formula, it does conform to type on the important points. Harry begins his adventure at Privet Drive after all, and there is a magic escape featuring six of his friends pretending to be him à la Polyjuice Potion. Harry, Ron, and Hermione, however, do not return to Hogwarts. Instead, they go into hiding from the Dark Lord and the Ministry while they search for Voldemort’s Horcruxes.

On their adventures, they confront bad guys and go underground repeatedly —into the depths of the Ministry of Magic, the dungeon beneath Malfoy Manor, and the caverns miles beneath Gringotts Bank, most notably —to search for Horcruxes and to liberate the imprisoned and falsely accused. Incredibly, it turns out at story’s end that all these trips underground, followed by resurrections from the dead in the presence of a symbol of Christ, were just foreshadowing for Harry’s sacrifice at the end of Deathly Hallows and his rising from the dead to defeat Voldemort —literally from King’s Cross —as a symbol of Christ himself.

There’s a lot more that needs to be said here about death, bereavement, and Christian symbols —which I’ll get to in chapter 7, chapter 9, and of course chapter 17 on the events and meaning of Deathly Hallows itself —but for now let’s leave the hero’s journey formula with these two key points:

The climax of Harry’s hero journey invariably turns out to be a strong image of the Christian hope that death can be transcended by love and in faith and specifically that believers have reason to hope in their individual resurrection in Christ.

The climax of Harry’s hero journey invariably turns out to be a strong image of the Christian hope that death can be transcended by love and in faith and specifically that believers have reason to hope in their individual resurrection in Christ. The answer these stories offer to the ultimate human problem —death —is always either love, Harry’s great power, or the symbol of Love himself, Jesus Christ.

The answer these stories offer to the ultimate human problem —death —is always either love, Harry’s great power, or the symbol of Love himself, Jesus Christ.

Why do people love these books? It’s not because the author is especially shy about answering the big human questions in story form or because she doesn’t point to specific enough answers! Every one of the seven Harry Potter novels and especially the last, Deathly Hallows, is built on the hero’s journey story structure. Rowling has given a peculiarly spiritual and undeniably Christian finish in Harry’s faux death and resurrection in the presence of or as a symbol of Christ. Readers don’t need to be Christians, of course, to find this ending thrilling and satisfying, or even an image of their greatest hope. The greatest human fear is of death, and sharing in Harry’s repeated and final victory over an enemy whose name means “willing death” brings readers back to the stories again and again for the vicarious pleasure of defeating death themselves. In a world largely stripped of the reality and inevitability of death, Harry Potter tackles the issue head-on in every story and gives a profoundly spiritual and specifically Christian answer: Love transcends death and defeats those who worship at death’s altar. Those who love sacrificially have hope of a personal resurrection on the example and in the person of Jesus Christ. Whether readers accept this last part or not —there is no altar call, after all —the message of personal immortality and love’s victory over death resonates in the human heart as a universal hope and explains in large part the widespread popularity of these books.

But there’s more! Rowling, believe it or not, has another storytelling superstructure with a strongly spiritual message on which she builds these stories. Turn the page for an introduction to literary alchemy, Rowling’s real magic for the transformation of her readers.