9

EVIDENCE OF THINGS UNSEEN

The symbols in Potterdom are powerful pointers to spiritual realities.

Do you groan when you read the word symbolism? If so, I bet I know why. You had a high school English teacher like mine who made sure you “got” the symbolism in everything you read —from the great White Whale in Moby Dick to the all-seeing billboard eyeglasses in The Great Gatsby. Problem was, she never explained how symbolism worked or why these supposedly great writers were spending so much time hiding what they meant behind silly images and metaphors. I figured it was just another adult game for writers and literature teachers to enjoy.

Boy, was I wrong. I will go so far as to say that this chapter on symbolism is the most important chapter in this book in terms of our ability to understand the popularity of Harry Potter, to understand the specifically Christian meaning of the books, and even to understand the right reasons for parents to object to stories their children are reading. Once we understand symbols we can better understand what it means to be human. As Christians who believe we are creatures made in “the image of God” (Genesis 1:26-27), we have to take seriously the idea, at least when studying English literature, that we are indeed three-dimensional symbols, in time and space, of the Trinity.

The world we live in is incomprehensible except in light of symbols. As Martin Lings, tutorial student and friend of C. S. Lewis, wrote:

There is no traditional doctrine which does not teach that the world is the world of symbols, inasmuch as it contains nothing which is not a symbol. A man should therefore understand at least what that means, not only because he has to live in the herebelow but also and above all because without such understanding he would fail to understand himself, he being the supreme and central symbol in the terrestrial state.[70]

Symbolism, it turns out, is not just an English major’s thing —it’s a human thing.

Let’s start by ridding ourselves of some of the mistaken ideas we may have been taught about symbolism. Symbolism is not something “standing in” for something else, a tit-for-tat allegory. An allegory is a story or word picture in which something existing on earth is represented by another earthly character or image. Some critics, for example, have written that The Lord of the Rings is an allegory of the Second World War, with Sauron and the forces of darkness standing in for the Axis powers while the Fellowship of the Ring and other white hats represent the Allies. As readers, we don’t interpret allegories as much as we translate them; allegories, unlike symbols, are just a translation of one story into another language or story. Neither are symbols simply signs, or at least they are not like street signs, which are simple representations for earthly instructions or things (such as Stop or Deer Crossing).

Literary characters and stories are not necessarily symbolic. Great novels like The Pilgrim’s Progress are allegorical both in regard to their characters and story line. Christian’s journey in Progress is a detailed picture of events and people met on every Christian’s earthly journey. The men that he meets —I think immediately of “Mr. Worldly Wiseman” (a great stand-in for television talking heads!) —are cardboard cutouts of people we meet every day who support or obstruct us in our passage to the heavenly Kingdom.

Many stories that are symbolic, however, are often mistakenly explained (and dismissed) as allegories. Please note that little else disturbed C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien as much as critical explanation of their fiction as “allegorical” (as in the WWII analogy). The reason their books touch us so deeply and have endured in popularity as long as they have is because of their symbolic meaning.

Symbols, rather than analogies for other earthly events, are transparencies through which we see greater realities than we can see on earth (see 1 Corinthians 13:12 and 2 Corinthians 3:18). The ocean as it stretches to the distant horizon is a symbol of the infinite power and breadth of the spiritual reality human beings call God. In seeing the one, we can sense the other. The ocean as a body of water has no power in itself to stir the heart; it’s just an oversized bathtub. But as a symbol of God, a way of seeing the unseeable, it can take our breath away or bring tears to our eyes.

Symbols are windows, too, through which otherworldly realities (powers, graces, and qualities) intrude into the world. As Lings wrote, this is the traditional understanding of Creation —that all earthly things and events testify to “the invisible things of him from the creation of the world” (Romans 1:20, KJV). This testimony includes the power of natural beauty and grandeur (think of mountain ranges, a field of flowers, or a lion on the savanna). It also includes sacred art, architecture, and liturgy, which are by definition symbolic in their portrayal of greater than earthly realities.[71]

Christ, of course, speaks in story symbols, too, through his parables. He knows we cannot understand the truth as it exists, so he wraps these truths in edifying stories or windows we can look through in order to experience some likeness of truth. “These things have I spoken unto you in proverbs: but the time cometh, when I shall no more speak unto you in proverbs, but I shall shew you plainly of the Father” (John 16:25, KJV). Until we see things “face to face” (1 Corinthians 13:12), though, we have symbols to understand ourselves and Creation.

The great revealed traditions teach that man, as an image and likeness of God, is a living symbol —both in the sense of transparency through which we look and of an opening through which God enters the world. Mankind is created in the image of God so that the world will reverence the God who cannot be seen (see 1 John 4:20 and the sequence of the Great Commandments in Mark 12:30-31). Humanity also is designed to be a vehicle of God’s grace, power, and love intruding into the world of time and space. The tragedy of man’s “fall” is that, because most people no longer believe they are symbols of God, shaped in his likeness, it is more difficult to see God in our neighbor, and the world is often denied access to God through his chosen vessels.

We are still moved, however, by the symbols in nature and the symbols that we experience in story form. This is the power of myth: that we can experience invisible spiritual realities and truths greater than visible, material things in story form. Tolkien described Christianity as the “True Myth,” the ultimate intrusion of God into the world through his Incarnation as Jesus of Nazareth. Tolkein’s explanation of this idea was instrumental in C. S. Lewis’s conversion to Christianity; it is this understanding of the purpose and power of story that gives his fiction its depth, breadth, and height.

Symbols in stories, just as the symbols in nature, sacred art, and edifying myths, are able to put us in contact with a greater reality than what we can sense directly. They do this through our imagination. The power of Lewis’s and Tolkien’s writing is found in their profound symbolism; The Lord of the Rings is not a strained allegory or retelling of WWII but a dynamic symbol of the cosmic struggle between good and evil of which WWII was also but a real-world representation.

What This Means for Understanding Harry Potter

Knowing that symbols are points of passage between this world and the greater world “above” —and “within” —us explains a lot about Harry Potter and Potter-mania. Magic, for example, is not demonic or contrary to Scripture when used (as it is in Harry Potter) as a symbol of the miraculous power of God that men as images of God are designed to have (see John 14:12 and chapter 1 of this book).

Books that are rich in symbolism necessarily support a transcendent worldview. The difference between believers and atheists or agnostics is that the secular crowd does not believe that anything exists beyond what can be sensed or measured. Everything is a this-worldly quantity. Christians and other believers understand the world to be a shadow of the reality of its Creator and that this greater reality —God —is rightly the focus of our lives. Symbolic literature requires —and celebrates —this otherworldly perspective that magically undermines the worldly, atheistic, and materialist perspective of our times.

This explains, too, why books that are rich in specifically Christian imagery and symbols are as powerful and popular as they are. Tertullian said that “all souls are Christian souls” and Augustine echoed him in writing that “our hearts are restless ’til they rest in Thee.” Tertullian was not making a sectarian argument contra Islam or Buddhism in saying “all souls are Christian souls.” Instead, he was pointing out the universal human end in the God who is Love. Since we as human beings are designed for the experience of this God, stories that retell the Great Story of our greater life in the Spirit satisfy the longing we are hardwired to feel and answer.

Unlike most contemporary novels, which portray realistic morals or earthbound allegories, Harry Potter is very much a myth pointing to the True Myth. Take, for instance, lead characters Harry, Ron, and Hermione. I already explained how Harry’s two friends are ciphers for the “quarreling couple” of alchemy, but there is a more profound symbolism the trio, Snape’s “Dream Team,” make up.

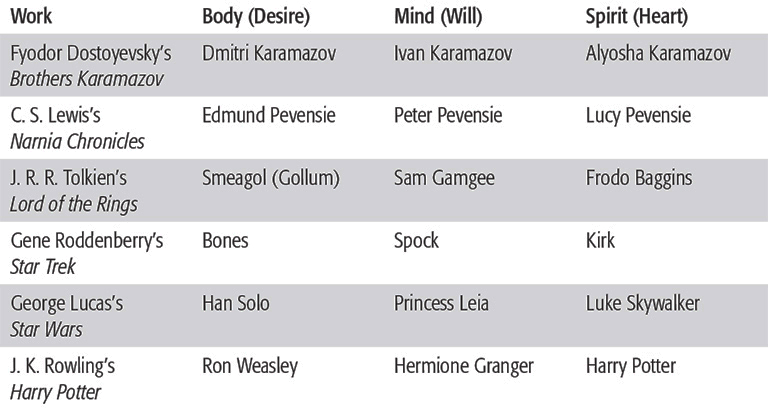

What’s great about this usage is that you’ve seen it before. Take a look at this chart:

Writers as different as Dostoyevsky and Tolkien, television producers and moviemakers, have all used this particular symbolism —because it works. Man is most obviously an image of God in that his soul is three parts; it has three faculties or powers symbolizing the three persons of the Godhead.[72] We call these powers “belly,” “head,” and “chest,” or more commonly “body,” “mind,” and “spirit.”[73]

Rather than try to show how these three principal faculties respond to situations as a sum in every character, artists can create characters that represent one of these faculties and show in story how these powers of the soul relate to one another. Every one of the original Star Trek television shows, for example, was a psychic drama of Kirk (spirit) leading Spock (mind) and Bones (body) against some outer-space adversary.

Harry, Ron, and Hermione can easily be connected with their corresponding faculties. Ron is the physical, comfort-focused complainer; Hermione, the thinker; and Harry, the heroic heart that leads the company.

So what? To understand the purpose and power of this literary model, take a moment to think of Harry, Ron, and Hermione’s relationships —when they work and when they don’t. Harry is clearly in charge. Hermione is the best thinker. Ron is the cheerleader and flag-waver (in his best moments). When they follow Harry’s lead in line —Harry, Hermione, Ron —all goes well. Think of their assault on the obstacles leading to the Philosopher’s Stone in the first book or their teamwork to get to the Chamber of Secrets: amazing work for preteens.

But when the team breaks down and the players don’t play their roles or won’t play them in obedience to Harry, things go wrong in the worst way. In the first six books, this happened twice, both times because Ron, low man in the hierarchy of faculties, takes the wrong role, and both of these times were pointers to his defection in Deathly Hallows.

In Prisoner of Azkaban, Ron takes the lead position. He gets into a bitter fight with Hermione about her decision to tell Professor McGonagall about Harry’s broom and then about her pet cat’s seeming to have made a meal of his pet rat. As Hagrid points out, a broom and a rat are hardly reason to throw off a friend, especially a friend in need; but no matter, Harry follows Ron’s passionate cues and stops speaking to Hermione. Harry also decides to go to Hogsmeade on Ron’s advice and against Hermione’s pleas —and narrowly misses being expelled. Lupin shames Harry; Ron comes to his senses, apologizes to Harry, and they reconcile with Hermione —with Ron again in a place of service to his friends.

In Goblet of Fire, Ron breaks entirely with Harry out of jealousy and meanness of spirit when Harry is chosen by the Goblet to be a school champion. Ron is pathetic on his own, and Harry misses his friend terribly, but he learned his lesson in Prisoner of Azkaban: the heart following selfish, spiteful passions gets you nowhere good, fast. Ron returns to the fold after the first Triwizard task, the danger of which seems to have jerked him back into remembrance of his rightful place in Harry’s service.

These two misadventures and reconciliations were only foreshadowing for Ron’s leaving Harry and Hermione in Deathly Hallows and his spiritual purification on his return in the Forest of Dean (see chapter 17’s discussion of “The Silver Doe”). As with the previous split and makeup, the trio and readers are in agony about the betrayal and longing for the return of order.

We should remember that it is Hermione who almost has nervous breakdowns during her time apart from Harry and Ron and during Ron’s breaks with Harry and with her. This is not feminine weakness, but rather a picture of the fragility of an intellect that is disembodied and heartless. Part of Hermione’s brilliance is her determined dependence on her friends; she understands that her jewel intelligence is glorious in its right setting and almost inhuman on its own (remember Hermione at the beginning of Philosopher’s Stone?). Her difficulty in accepting Ron’s return in Deathly Hallows speaks to her greater injury in his absence.

In Order of the Phoenix, Harry is separated from Ron and Hermione by virtue of their being selected as house prefects. Ron and Hermione both flourish as they take on responsibilities independent of Harry —and at the same time, their appreciation for him and their friendship grows apace. The trio’s love for one another and our identification with them makes their hard times with each other the most painful parts of the stories —and their reconciliation the most joyous. We become aligned in this identification —spirit to mind to body —and feel strangely upright and all right for the change.

Good literature trains us in the “stock responses” and lets us see and pattern ourselves after the right alignment of the soul’s powers. When our desires are in line with our will, and both will and desires are obedient to directions from the heart or spirit, we are in operation the way we were designed to be, “spirit side up,” if you will. Turn this upside down, though, so that will and spirit answer to the desires (as the commercials in our desire-driven culture would have it), and you have a wreck-in-the-making. The human person isn’t designed to be belly-led, as Scripture, history, and experience all testify (see Romans 16:18 and Philippians 3:19, and visit any one of the addiction recovery programs in your neighborhood for verification).

Mythical Beasts in Harry Potter

For most of us, the connection between an animal and its symbolic quality is pretty clear. A dog embodies and radiates the virtue of loyalty; a cat, feminine beauty and grace; a lion, power and majesty; an eagle, freedom; and a horse, nobility.

The animals in Harry Potter, though, are not your conventional domestic pets or zoo beasts. Rowling has a rich imagination and a special fascination for fantastic beasts; she has even written a Hogwarts “schoolbook,” Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, cataloging her favorites, A–Z. Are these products of her imagination symbols in the way eagles and lions are symbols?

Yes and no. No, I don’t think a fictional lion (say, the one that occurs throughout the Potter books on the banners of Gryffindor House or the lion Aslan in Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia) has the same power to suggest “majesty” as a real lion on the savanna. One works through the sense of vision and the other through the imagination. But, yes, if the fictional beast is capably depicted, both contain the quality that makes the lion regal and stirs the heart.

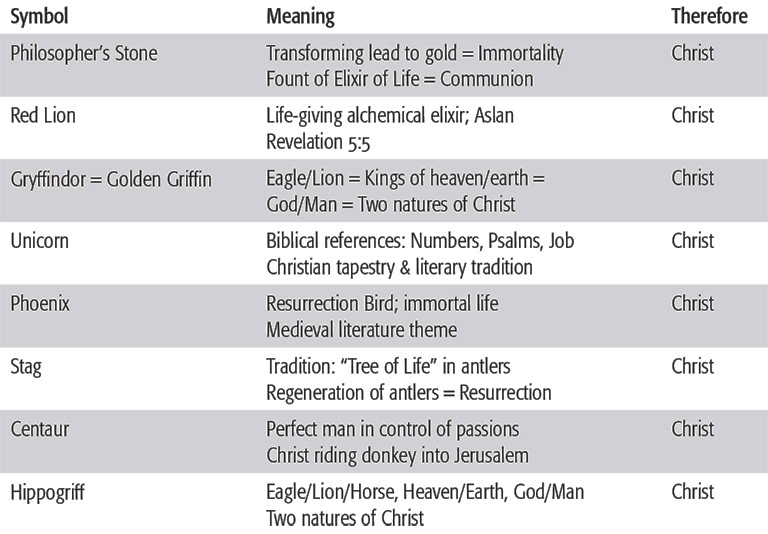

Many of the animals in Harry Potter are Rowling’s own inventions (although the acromantula reminds Tolkien fans of the giant spider Shelob and of the den of spiders in The Hobbit). However, let’s focus on traditional symbols from European and especially English literature because of the wealth of references that support the interpretation of their supernatural qualities. If there is a single giveaway of the transcendent and specifically Christian meaning in Harry Potter, it is in the uniform meaning of the symbols. The magical creatures and figures we will look at more closely are the griffin, the unicorn, the phoenix, the stag, the centaur, the hippogriff, the Philosopher’s Stone, and the red lion. Each is a traditional symbol of arts and letters in the English tradition used to point to the qualities and person of Christ.

THE GRIFFIN

I’ve found only two mentions of a griffin per se in the Harry Potter books, and they are details mentioned in connection to Dumbledore’s office. Professor McGonagall is bringing Harry there in Chamber of Secrets after he has been discovered next to the petrified forms of Justin Finch-Fletchley and Nearly Headless Nick: “Harry saw a gleaming oak door ahead, with a brass knocker in the shape of a griffin.”[74] The password keeper on the stairs leading to Dumbledore’s office that Harry passes twice in the last chapters of Deathly Hallows is also a griffin.

The griffin is described in Fantastic Beasts as having “the front legs and head of a giant eagle, but the body and hind legs of a lion.”[75] It is an important symbol in the Potter series, though only mentioned at Dumbledore’s office entrance, because “Harry’s House, Gryffindor, literally means ‘golden griffin’ in French (or is French for ‘gold’).”[76] So spell it “Griffin d’or.” As Harry is considered a “true Gryffindor” in Dumbledore’s estimation,[77] you can put a bet on there being great significance in the meaning of golden griffin for the identity of Harry Potter.

How does a beast that is half lion and half eagle symbolize Jesus Christ? Two ways. First, Christ is the God-Man, so double-natured symbols are a natural match for him. More important, though, is that the two natures here are the lion and eagle. A beast that is half “king of the heavens” (eagle) and half “king of the earth” (lion) points to the God-Man in his role as King of Heaven and earth.[78]

THE UNICORN

Harry first meets a unicorn in the Forbidden Forest under the worst of conditions. The unicorn is dying or dead; Voldemort, as something like a snake, is drinking its blood, which “tonic” curses the drinker but keeps him alive.[79] Unicorns pop up again in Ms. Grubbly-Plank’s and Hagrid’s Care of Magical Creatures Classes.[80]

I remember as a young boy being taken to the Cloisters, a New York museum of medieval art in an authentic castle brought stone by stone from Europe. The highlight of the trip was the tapestries —specifically the unicorn tapestries. The guide told us that the unicorn was the symbol of Christ preferred by the weavers of these giant pieces. Though I was a child of no special faith (or sensitivity), I was moved by the images of the unicorn being chased, captured, and resting its head on a virgin’s lap.

A check in Strong’s Concordance to the Bible reveals mentions of unicorns in the Old Testament books of Deuteronomy, Numbers, Job, Psalms, and Isaiah.[81] One Harry Potter guidebook comments that “these references, to some scholars, indicate that the unicorn is actually a symbol of Christ.”[82] Scholars of symbolism as diverse as Carl Jung and Narnia expert Paul Ford confirm this interpretation of the pure white animal whose single horn symbolizes the “invincible strength of Christ.”[83]

As we’ll see in the chapter on Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, the unicorn as a symbol of Christ is essential in understanding the meaning of the dramatic scene in the Forbidden Forest during Harry’s detention with Neville and Draco.

THE PHOENIX

My flat-out favorite beastie in Rowling’s menagerie is Fawkes the phoenix, Dumbledore’s pet. Harry meets him in Chamber of Secrets on a “dying day” when Fawkes bursts into flame and rises as a chick from his own ashes.

Given Fawkes’s role in the defeat of the basilisk in Chamber of Secrets, Harry’s draw with Voldemort in Goblet of Fire in the cage of phoenix song and light, and that Dumbledore’s adult army in opposition to the Dark Lord is called the Order of the Phoenix, this symbol is central to any interpretation of the books or understanding of their power and popularity. How is the phoenix a symbol of Christ? In the Middle Ages the phoenix, because of its ability to “rise from death,” was known as the “Resurrection Bird.” Like the griffin, it was used in heraldic devices and shields to represent the bearer’s hope of eternal life in Christ.[84] A sure pointer to this symbolism comes in the climactic battle between Dumbledore and Voldemort in Order of the Phoenix. Voldemort has managed to get the drop on his headmaster nemesis and shoots out the death curse, Avada Kedavra. Fawkes the phoenix dives between Dumbledore and certain death, swallows the death curse in his place, explodes into flames, and rises from the dead on the spot. The phoenix here, of course, portrays not only the Resurrection of Christ but also the Christian belief that he has intervened for humanity and taken the curse of death upon himself.

THE STAG

Lupin and Black explain to Harry in the crucible of the Shrieking Shack that his father, James, was an animagus. Harry discovers later that night what form his father took: a majestic stag with a full rack of antlers. His nickname at school, Prongs, came from these antlers, which are the stag’s weapon and defining characteristic.[85] That Harry’s Patronus likewise takes the shape of a stag gives this already powerful symbol even more importance.

Narnia fans recall that the Pevensie children in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe only return to Earth from their Narnia kingdom because, as kings and queens of Narnia, they pursue the White Stag into a thick wood. Lewis points to their search for Christ as the cause of their return, because Christ is to our world what Aslan is to Narnia. The stag can be described as “a beast, the quest of great hunting parties, who was said to grant wishes to his captors. Lewis, as a student of the Middle Ages, would know of the symbolism of the stag for Christ”[86] (emphasis added). Maybe you don’t see how a big deer can link our world and the Christian creative principle.

It’s simple, really. The power of the symbolism comes from the antlers. Just as the phoenix is the “Resurrection Bird” because it can rise from its own funeral pyre, so the noble stag “came to be thought of as a symbol of regeneration because of the way its antlers are renewed.”[87]

The stag’s antlers break off and grow back, tying the animal symbolically to the tree of life and the Resurrection. Given this correspondence, it is no accident that when Harry first sees the stag Patronus who saves him from the Dementor’s kiss —the living, soulless death worse than death —he sees it “as a unicorn.”[88] The stag in Harry Potter, like the unicorn, is a symbol for Christ.

THE CENTAUR

Fawkes is great, but my favorite character in literature may be a centaur out of Narnia because of his last words. In The Last Battle, the centaur Roonwit —literally “he who knows the ancient languages”[89] —reveals to King Tirian the signs that calamity is about to strike Narnia. The king sends him on a dangerous mission, and Roonwit is shot by the archers of invading Calormenes he has been sent to spy on. But he sends this edifying, otherworldly message as he expires: “Remember that all worlds draw to an end and that noble death is a treasure which no one is too poor to buy.”[90]

C. S. Lewis, renowned classicist and medieval scholar of Oxford and Cambridge, was certainly familiar with the conventional interpretations and uses of the centaur as symbol. His centaurs in the Chronicles of Narnia are often of this reveling type, but in Roonwit’s case the centaur is heroic and sacrificial in service to the King. In Harry Potter, similarly, we have passionate centaurs and one heroic example, Firenze, who saves Harry from Voldemort in Philosopher’s Stone.

The centaur is first and foremost a symbol of man. It has the head and chest of a man and the body of a horse. The head and chest of a man are man’s will, thought, and spirit; the horsey bottom is his desires or passions. The centaur is a comic picture of a man’s dual nature as angel and beast. When man is right side up, his angelic part tells the horse desires what to do, as a rider directs a horse; when the beast is in control, however, the belly of the horse drags the chest and head where it wants like a runaway pony.[91] We see the donkey centaurs in Half-Blood Prince and Deathly Hallows where the herd in the Forbidden Forest refuses to help Harry and fight the Dark Lord until they are shamed by Hagrid and by seeing Harry’s seeming corpse. Then they come to themselves, man over donkey, and lead what seems a suicidal charge on the Death Eaters and the Dark Lord.[92]

The heroic centaurs Roonwit and Firenze and these repentant champions in Hallows are all symbols of Christ because, as caricatures of men, they are also imaginative “images of God.” Through these characters, Lewis and Rowling refer to a tradition that links a man on a passionate beast with heroic, sacrificial, and saving actions: Christ riding into Jerusalem in triumph on a donkey.

The traditional Christian explanation of why Christ rides in triumph into Jerusalem on a donkey rather than a noble steed is that he wanted to show the hosanna-shouting assembly on the sides of the road a three-dimensional icon or symbol of the obedient man. Thus the donkey (certainly a picture of willful, stubborn desire) serves his master, Spirit and God incarnate, in cheerful obedience. Roonwit and Firenze give us this scriptural image of the God-Man and the rightly ordered soul . . . another symbol of Christ.

THE HIPPOGRIFF

I confess to initially thinking that Buckbeak the hippogriff was another one of Rowling’s mythological innovations —and a hoot. I had certainly never heard of one. Turns out, it is the creation of a sixteenth-century Italian court poet named Ludovico Ariosto in his Orlando Furioso.[93] The original hippogriff, of whom Buckbeak must be a descendant, is a griffin/centaur cross. “Like a griffin, Ariosto’s hippogriff has an eagle’s head and beak, a lion’s front legs, with talons, and richly feathered wings, while the rest of its body is that of a horse. Originally tamed and trained by the magician Atalante, the hippogriff can fly higher and faster than any bird, hurtling back to earth when its rider is ready to land.”[94] The hippogriff is “a kind of supercharged Pegasus, a blend of the favourable aspects of the griffin and the winged horse in its character as the ‘spiritual mount.’”[95]

Hippo is the Greek word for “horse” (a hippopotamus is a “river-horse”), and griff takes us back to the griffin. A hippogriff, then, is a combination horse/lion/eagle, or a centaur with a lion/eagle “top.” We have already learned how the griffin in Gryffindor is a symbol of Christ as King of Heaven and earth. As a griffin/centaur, the hippogriff, too, suggests Christ’s divine conquest of the passions, as evidenced by his donkey ride into Jerusalem.

Hagrid describes hippogriffs to his students as “proud,” but they are not proud in the sense of conceit or vanity. They are great-souled and aware of their virtue, which the ignoble misunderstand (Hagrid loves them dearly; he knows!). The noble —even supernatural —Buckbeak in Prisoner of Azkaban pecks the disrespectful and shameless Malfoy, is persecuted by the godless Ministry, and is almost executed by the Death Eater McNair. He escapes death at the hands of a world that cannot understand him (and that chooses to hate and fear him) to serve as Sirius’s salvation. As with the griffin’s and centaur’s double-natured symbols, Rowling uses the hippogriff as a symbol of Christ, the God-Man.

THE PHILOSOPHER’S STONE

The end result of the alchemical Great Work was a stone that produced the Elixir of Life (an elixir often called “the red lion”). This magical object, known as the Philosopher’s Stone, gave its owner immortality (as long as the owner drank the elixir) and infinite wealth. Touching any leaden or base metal object to the Stone would make it turn to gold.

Historians of science, religion, and literature agree on very little, in my experience. However, they do agree that the Philosopher’s Stone is a symbol of Christ.[96] There isn’t anything else in the Western spiritual tradition that promises eternal life and golden (that is, incorruptible or spiritual) riches except Christ, so the connection is transparent. The end product or aim of alchemy is life in Christ; English authors and poets of many centuries have used this symbol of Christ, consequently, to dramatize the search for an answer to death and human poverty of spirit. Harry Potter is no exception, as we will see in chapter 11 on Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.

THE RED LION

Narnia fans have told me they do see Aslan, Lewis’s Christ figure from the Chronicles of Narnia, in the Gryffindor House lion symbol. I think that is a reasonable link, especially in light of the symbolic meaning of Gryffindor and its opposition to the Slytherin serpent. This idea, however, hasn’t been “lifted” from Lewis —the lion, and specifically the red lion, has been a symbol of Christ from the first century.

Saint John the Evangelist had no need to explain this usage in the book of Revelation: “Weep not: behold, the Lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David, hath prevailed” (Revelation 5:5, KJV). It is a theme of Christian literature and heraldic signs, consequently, throughout the Middle Ages. Lewis draws from this tradition both for Aslan (Persian for “lion”) and Aslan’s devotees in Narnia. Remember Peter’s shield? “The shield was the color of silver and across it there romped a red lion, as bright as a ripe strawberry at the moment when you pick it.”[97] The seven Harry Potter books are full of alchemical imagery, and even if Lewis was unaware of it (the silver and red in Peter’s shield makes me doubt his ignorance), we can assume Rowling knows what the “red lion” means to an alchemist.[98] The “red lion” is the Elixir of Life coming from the Philosopher’s Stone, a symbol of the blood of Christ received in Communion. The Stone in the first Harry Potter book, in case we missed this point, is described as “blood red.”[99] The red lion, then, is still another symbolic point of correspondence between Christ and the world of Harry Potter.

The following chart recaps the eight symbols of Christ we’ve examined:

Does it seem odd that there are so many symbols of Christ? There is a big difference between symbols and allegorical figures. Allegories are stand-ins or story translations of a worldly character, quality, or event into an imaginative figure or story. There can be only one figure representing the other, consequently, or it’s difficult to translate; I cannot have two Hitler figures if I’m writing an allegory of the Second World War, or the allegory fails.

Symbols, in contrast, can be stacked up. If I am telling a fantasy story with a transcendent meaning, even a Christian message, I can include characters and beasties and events that all point to the various qualities, actions, and promises of Christ. Rowling, depicting Dumbledore’s suffering in the cave and in his death on the Astronomy Tower in Half-Blood Prince, is writing in story form of Christ’s death on the Cross at Calvary.[100] If the symbols correspond with these qualities, even if they are not consciously understood as Christ symbols, they open us up to an imaginative experience of those supernatural qualities. A variety of these symbols woven into a story that itself echoes the Great Story will powerfully stir even the unconscious or spirit-denying soul because the heart of homo religiosis is tuned to these specific spiritual frequencies that cannot be totally shut down. Our cardiac intelligence radios are always tuned to the frequency of spiritually laden symbols transmitted through story.

The Harry Potter stories, in their formulaic journeys that end every year with love’s triumph over death in the presence of a Christ symbol, find their power and popularity in the resonance they create in our hearts. We connect with them because they point toward the True Myth that lifts us above our mundane ego concerns. So much of Harry Potter —the symbols of Harry, Ron, and Hermione; the drama of the soul’s faculties in action; the imagery of the many beasts; the windows into Christ’s role in the Great Story; and the stories themselves —all foster a Spirit-first perspective by “baptizing the imagination.”[101] Even neglecting the transparent Passion narrative at the end of Deathly Hallows, a powerful symbolic message about the spiritual realities celebrated in the Christian tradition has rarely, if ever, been smuggled into the hearts and minds of readers so successfully and profoundly.

Now that we have examined the formulas, themes, and symbols of the books, we have only to detour briefly to decipher the secret names many Harry Potter characters have before jumping into the stories themselves.

Ever wondered what Neville Longbottom means? Keep reading.