2

ORDER AND ANXIETY

October 21st 1805

8.30 am to 9.30 am

Distance between fleets: 6.5 miles–5.9 miles

Victory’s heading and speed: 034°–067° at 2.5 knots

Order is Heav’n’s first Law

ALEXANDER POPE, Essay on Man, 1734

As the British ships made their slow progress to the eastward, the crews were struck by the beauty of the spectacle they were creating. In the log of the Mars, Thomas Cook, her master, described what the men were about this morning: ‘making Ship perfectly clear for Action’. The clarity before battle was a form of perfection. It was the beauty of order and arrangement, each part of each ship designed for its task, each related to and dependent on all others, a network of interaction. Forget for a minute that these are killing machines. Years later, Midshipman Hercules Robinson of the Euryalus reminisced:

There is now before me the beautiful misty sun-shiny morning of the 21st October. The delight of us all at the idea of a wearisome blockade, about to terminate with a fair stand-up fight, of which we knew the result. The noble fleet, with royals and studding sails on both sides, bands playing, officers in full dress, and the ships covered with ensigns, hanging in various places where they could never be struck.

According to John Brown, a seaman on Victory, ‘the French and Spanish Fleets was like a great wood on our lee bow which cheered the hearts of every British tar in the Victory like lions anxious to be at it.’ Nelson, again and again, commented to the frigate captains he had summoned on board Victory how much the enemy were standing up for a fight, not running and scattering to all corners. The scene looked as these moments were intended to look: a clash of organisations in which men, ships, fleets, naval systems and countries were to be put to the test.

The Euryalus had been in close to the mouth of Cadiz harbour on the preceding days, looking for the slightest sign of enemy preparation. Midshipman Robinson remembered how

The morning of the 19th of October saw us so close to Cadiz as to see the ripple of the beach and catch the morning fragrance which came out of the land, and then as the sun rose over the Trocadero with what joy we saw the fleet inside let fall and hoist their topsails and one after another slowly emerge from the harbour mouth.

His captain, Henry Blackwood, had written on the 20th to his wife in England:

What do you think, my own dearest love? At this moment the Enemy are coming out, and as if determined to have a fair fight. You see also, my Harriet, I have time to write to you, and to assure you that to the last moment of my breath I shall be as much attached to you as man can be, which I am sure you will credit. It is very odd how I have been dreaming all night of my carrying home dispatches. God send so much good luck! The day is fine; the sight of course, beautiful…. God bless you. No more at present.

Captain Edward Codrington on the Orion wrote smilingly to his wife:

We have now a nice air, which fills our flying kites and drives us along at four knots an hour…How would your heart beat for me, dearest Jane, did you but know that we are under every stitch of sail we can set, steering for the enemy.

Codrington missed Jane with a passion, writing to her that he was ‘full of hope that Lord Nelson’s declaration would be verified; viz. that we should have a good battle and go home to eat our Christmas dinner.’ On the Belleisle, Lieutenant Paul Nicolas described how

I was awakened by the cheers of the crew and by their rushing up the hatchways to get a glimpse of the hostile fleet. The delight manifested exceeded anything I ever witnessed, surpassing even those gratulations when our native cliffs are descried after a long period of distant service.

They were seeing battle as home, as the moment of perfection, with the sweet-smelling scents of Iberia wafting across the stretch of sea at which they had arrived, and the Atlantic breakers beyond it creaming on to the sand.

Over this very stretch of sea, 18 months before, Samuel Taylor Coleridge had sailed to Malta in convoy, shepherded by Captain Henry Bayntun in HMS Leviathan. For the poet it was a passage of troubled but at times ecstatic happiness, running from opium and hopelessness in England to the warmth of the Mediterranean. His journal of the voyage speaks, in a way no naval officer could, of the beauties which were so clearly felt on the morning of Trafalgar. ‘Oh with what envy I have gazed at our commodore,’ Coleridge wrote, half in love with ships,

the Leviathan of 74 guns, the majestic and beautiful creation, sailing right before us, upright, motionless, as a church with its steeple – as though moved by its will, as though its speed were spiritual.

This morning, Tuesday April 10th, 1804, a fine sharp morning – the Sea rolls rough & high / but the Ships are before us & behind us. I count 35, & the lonely Gulls fish in among the Ships / & what a beautiful object even a single wave is!

Delightful weather, motion, relation of the convoy to each other, all exquisite/ – and I particularly watched the beautiful Surface of the Sea in this gentle Breeze! – every form so transitory, so for the instant, & and yet for that instant so substantial in all its sharp lines, steep surfaces, & hair-deep indentures, just as if it were cut glass, glass cut into ten thousand varieties / & then the network of the wavelets, & the rude circle hole network of the Foam /

And on the gliding Vessel Heaven & Ocean smil’d!

That is a line from one of Wordsworth’s poems in Lyrical Ballads, in which the female vagrant who speaks is in a wretched condition herself but can nevertheless grasp the beauty in the gliding Vessel before her. That is Coleridge’s predicament too, broken himself, but in love with the orderliness of the Leviathan’s convoy around him.

On the morning of the 21 October 1805, with the huge bluff ships surging beneath them and the sails slatting in the swells, there was little to do but contemplate the excellence of their own fleet and the prospect of violence to come. In the steady breeze and on the constant course, there was little need to adjust the trim of the sails. The only movement was at the wheel, where the helmsman steered to port as the swell lifted beneath him, to starboard as it dropped the bow in the trough that followed. Men had breakfast. Captains showed their lieutenants Nelson’s memorandum, in case they were ‘bowled out’ in the action and the lieutenants needed to take command. On the poops, their bands played ‘Rule Britannia’, ‘Britons strike home’ and ‘Hearts of Oak’, first written after the triumphant victories of 1759, the Annus Mirabilis of the Seven Years War:

Come, cheer up my lads,

It’s to glory we steer,

To add something more

To this wonderful year.

To honour we call you,

As free men, not slaves,

For who are so free

As the sons of the waves?

Half the people who sang that were either pressed men or miscreants sent on board as part of a quota from each county, and a sixth of the entire fleet would desert or attempt to desert in the coming year (an average kept up throughout the Napoleonic war). Their average age was under 22. But the power of the British self-image as free men was such that in all probability these men believed what they sang: theirs was an honourable condition of freedom and order.

This profound shipboard orderliness was no chance effect. The ship itself was to be a model of order. Sail-makers were to see that sails were dry when they went into store, to make sure they were aired and to secure them from ‘drips, damps and vermin as much as possible.’ Proper sentinels were to be posted ‘to prevent people’s easing themselves in the hold or throwing anything there that may occasion nastiness.’ Rather than order, the prevention of disorder was the essence of naval life. Written Admiralty instructions required the boatswain and his mates on each ship ‘to be diligent…and see…that the working of the ship be performed with as little noise and confusion as possible.’ The ship, in fact, is to be worked in silence or near-silence. The repeating of orders was thought to be a symptom of slightly inadequate management.

In a world where the orderliness of things seems so close to disorder and disintegration, an almost dance-like form of behaviour, in which the set moves are made with some grace and precision, was a kind of bulwark against chaos, a guarantee of who you were. On these ships, theatricality of language and dress was more than mere display: it was a mark of civility and order, of a distance from the anarchic mob, of precisely the values for which the war against revolutionary-cum-imperial France was being fought. ‘Even a momentary dereliction of forms,’ one ship’s chaplain wrote, ‘might prove fatal to the general interest.’ St Vincent had insisted that his captains should remain aloof from their men and even from their brother officers. The idea of a captain eating dinner with his lieutenants appalled him. Distance was a method of command. It is the same instinct for order which lies, for example, behind an instruction issued by Lord St Vincent to the Mediterranean fleet in July 1796. The admiral wasn’t going to have any hint of casual drawing-room manners, nor the wit of elegant society, about his fleet or flagship:

The admiral having observed a flippancy in the behaviour of officers when coming upon the Victory’s quarterdeck and sometimes in receiving orders from a superior officer and that they do not pull off their hats and some not even touching them, it is his positive directions that any officer who shall in future so far forget this essential duty of respect and subordination be admonished publically; and he expects the officers of the Victory will set the example by taking their hats off on such occasions and not touching them with an air of negligence.

St Vincent was insistent that midshipmen should have a uniform ‘which distinguish their class to be in the rank of gentleman, and give them better credit and figure in executing the commands of their superior officers.’ Decks were to be swept at least twice a day, the dirt thrown overboard, men to change their linen twice a week, to wash frequently, to make sure the heads were clean every morning and evening. The ship was to appear ‘clean and neat from without board.’ These orders, written in order books, were to be kept on the quarterdeck and open to inspection ‘of every person belonging to the ship’, sometimes in a canvas case.

Filthy language, the solid staple of life between decks, was nevertheless not to be used within the hearing of officers. ‘There is a word which only comes from the mouths of hardened blackguards,’ wrote the extremely clean-minded Captain Riou on the Amazon in 1799, ‘that will not be permitted to pass with impunity.’ What that word was can only be guessed at but certainly Captain Griffiths on the London in 1795 thought ‘“Bugger” a horrid expression disgraceful to a British seaman, a scandalous and infamous word.’ Not as scandalous as the act itself, which seems to have been committed rarely, and only then down in the unlit spaces in the depths of the ship, on the cable tier, where love, lust or dominance could have its way with least chance of disturbance.

The essence of the order was of course vigilance, and the roots of vigilance reached far down into the souls of the officers themselves. Officers and men lived, critically, on either side of a moral watershed: an officer’s self-control was the source of the discipline which he then imposed on the men. The state of a ship and its company was a test of the officer’s inner, moral qualities and each ship needed to be, in effect, a diagram of that highly regulated state. It was a difference which meant that the violence done by officers to men was seen as almost unequivocally good; and violence done by men to officers just as unequivocally bad. A man’s duty was to obey, an officer’s to be right and so, as an aspect of nothing but logic, a man’s failure was a cause for punishment and an officer’s a cause for dishonour.

Every aspect of the ship was to conform to this image of order. The stores were to be stored ‘with economical exactness.’ No excuse would be admitted for stores ‘not being neatly arranged and ready to hand.’ The officer of the watch was

to be careful that the sails are at all times well hoisted, reefs repaired if required, sheets home, yards braced, trusses, weather braces and bowlines attended to, and the sails in every respect as properly set as if the ship was in a chase.

‘Minute attention’, ‘her exact place’, ‘a uniform system of discipline’: every phrase reinforced the sense that not only was the ship a fighting machine but a microcosm of rational civilisation, surviving in and threatened by a chaotic and hostile world, a zone of chaos to which the ship’s company naturally belonged. The terror with which mutiny was viewed, and with which the mildest whisper of mutinous thought was received, was a measure of the tightness with which the line of order was drawn. For the first lieutenant, in effect on test for promotion to captain, the demands of the system could not be more absolute:

It is impossible he can be too minute in these particulars of his duty. He ought to know everything, see everything and have to do with everything that is to be known, seen or done in the ship.

He was, in other words, to be Enlightenment, Virgilian man, the representative of civilisation, entirely aware, entirely informed, entirely in control and as a result entirely admirable. From the cleanness and regularity of his heart and mind would ‘follow credit and comfort to a well disposed ship’s company.’ There were some deeply traditional aspects to this. Buried deep within the 1805 conception of the naval officer was a Roman and stoical image of distilled order, of an applied and balanced rationality which both constituted and oiled the fleet system itself. A fleet was an act of English civility. Its orderliness was its virtue, rationality its fuel, clarity its purpose, and in those qualities, the English had long congratulated themselves that they were different from foreigners. After the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, a thrilling discovery was reported in London:

strange and most cruell Whippes which the Spaniards had prepared to whippe and torment English men and women: which were found and taken at the overthrow of certain of the Spanish Shippes.

The implication, of course, is that no such violence would be natural to an Englishman. No, the English were honest, plucky little fighters against wicked European tyrants and many elements of what would come to be seen as the Nelson persona were in fact utterly conventional parts of this English naval self-image. A rough broadsheet song described the virtues of Rear-Admiral Richard Carter, killed against the Dutch at la Hogue in 1692:

His virtue was not rugged, like the waves,

Nor did he treat his sailors as his slaves:

But courteous, easy of access, and free,

His looks not tempered with severity.

Change the idiom slightly and those are precisely the terms in which Nelson was described a century later.

Needless to say, though, this straining for order, for the idea of the beautiful machine was founded on an overriding sense of anxiety. Naval order was little more than a thin and tense veneer laid over something that was on the boundaries of the chaotic. Rationality was merely a dreamed-of haven in all the oceans of contingency. Order, it turns out, was in many ways little more than a rationalisation of chaos, anxiety and corruption. The great Admiral Vernon had warned in the 1770s that ‘our fleets are defrauded with injustice, marred by violence and maintained by cruelty.’ The amount of money voted by parliament each year to pay the seamen was not only calculated on a scale unchanged since the days of Oliver Cromwell but the amount voted never corresponded to the number of seamen raised. No audit was ever done to see how the money was spent and enquiry after enquiry in the late 18th century did little to cure the wastage and muddle. Seamen’s pay was often years behind, the principal and justifiable cause of the great mutinies of 1797.

It was generally known that the administration of the navy and its dockyards was a mass of deceit and inefficiency. As one contemporary pamphleteer wrote, it was a scene consisting of

gigantic piles, and moles, and misshapen masses of infamy, where one villainy is the buttress of another; where crime adheres to crime; and fraud ascends upon fraud, inserted, roofed, dove-tailed and weather-proofed with official masonry, and the unctuous mortar of collusion. [The navy was] the central temple of peculation: where the god of interest is worshipped under the mystic form of liberality, and the common conscience of guilt is professed under the symbol of mutual charity and conciliation.

Everyone, in other words, was on the make. The great Earl St Vincent had attempted reform and his brief tenure as First Lord of the Admiralty had ended with a savage attack on him, his competency and his methods in the House of Commons by William Pitt himself. His successor as First Lord of the Admiralty, Pitt’s closest friend Lord Melville, had been found guilty of at least borrowing from the state purse. When Barham succeeded him, he was at that time still Sir Charles Middleton, 80 years old, a seasoned naval administrator. Middleton accepted the job on one condition, quite explicitly expressed in a letter intended for Pitt’s ear but addressed to Melville: he wanted to be a lord. ‘I have no other wish towards the admiralty,’ he wrote from his elegantly rustic farm set among the orchards and woods at Teston in Kent, ‘but to secure the peerage to myself and family. The admiralty has no charms for me, further than to serve and promote these objects. The opportunity that offers at present to secure me the peerage must be obvious to Mr Pitt, and it would be a reflection on good sense to suppose his Majesty would be adverse to bestowing a mark of approbation on my many years services, and coming out again in the decline of life, at the desire of his ministers.’ He got the title, became Lord Barham and took the job. Enlightenment London knew all about self-promotion.

In daily detail, life on board a ship-of-the-line was thick with an atmosphere of supervision, anxiety and the endless efforts at maintenance and mending. Order was achieved in a condition of near-anarchy. Take as a pair of complementary documents, a list of boatswain’s stores (to be checked, to be tested against theft and loss) and a ship’s surgeon’s list of what was wrong with the men, and you can read from them exactly what dominated the 1805 man-of-war.

So for example, the boatswain’s stores on HMS Thunderer, a 74-gun ship, as recorded on 10 October 1805 included 35 gallons of black varnish; eleven large brushes, three small; 90 lbs of ground yellow paint; 863 yards of canvas of eight different grades and another 100 yards ‘old’ canvas; 5 ensigns, 4 jacks, 8 pendants; 1237 hammocks, 631&frac;2 yards of kersey; 1 fish copper kettle, one small fish copper kettle, 1 machine for sweetening water; 1 machine for making cordage and 9,500 feet of spare cordage; 202 iron cringles; six boat grapnels; 7 hatchets; 24 boat hooks and a fish hook; 16 marline spikes; 78 sail needles and 12 sail making palms; 68 thimbles; 56 leather buckets; 11&frac;2 tons of vinegar and 21&frac;2 barrels of tar; 68 spare sails and 72 spare blocks; a 32-ft barge, a 31-foot-long boat, a 28-ft pinnace, two 25-ft deal cutters and a ten-foot four-oared boat, plus all their oars. The ship itself had a pair of giant sweeps with which to propel it in a calm. There were two 70-fathom seine nets, and a mass of fishing gear for albacore, dolphin and bonito, plus some shark-fishing gear fitted with a chain. There was a mackerel line but no turtle nets. The Thunderer carried a Dutch ensign, as well as a French and a Spanish one; a Dutch, Spanish and French jack and a Dutch, Spanish and French pendant, all of which could be used to disguise her identity or to trick the enemy. The stores themselves are a record of vigilance and danger, of damage foreseen and emergency accounted for. It is a world of shattered spars and blown-out sails, men and objects lost overboard, worn sheets and frayed halyards, blocks split and lost, hammocks torn, lift tackles gone, lanyards broken. It feels nearly comfortless.

Alongside it, one can place the list of complaints with which a ship’s surgeon would have to deal, the human impact of this strained life in the damp, dangerous world of a man-of-war: ulcer of frenum of the penis; drunk falling from deck on keelson; hands caught in block; catarrh; rheumatism; diarrhoea; contusion; colic; falling while hauling on the braces, causing venereal hernia; fall while taking down the hammocks, producing dislocated shoulder; letting an adze slip while repairing a cutter and the blade cutting into his Achilles tendon; slipping and falling into tender (a boy aged 16); fractured humerus falling on deck in a wind; rheumatism in the knees; tonsillitis; inflamed glands in groin; ‘fell on deck with four or five men over him in a gale’; stabbed in forehead when ashore; fell out of his hammock on to deck; falling down drunk; a fall into the waist; ankles swollen; epilepsy, (the prospect of which aloft was terrifying); guts – griping, discharge of blood, faeces scanty and white; severe pain in loins; right hand dragged into a block, ends of fingers fractured; sole of left foot punctured by a scrape. More often than not men took several days before they reported they were hurt. One was said to complain simply of ‘Hypochondriasis’. Others, for whom the strain was too much, are described merely as ‘hectic’ or ‘withdrawn’. ‘Mania’ afflicted all categories of men on board.

It is remarkable, in the light of the deeply demanding conditions in which it operated for years at a time, that the navy of 1805 achieved what it aimed for. Deep orderliness was a quality which struck visitor after visitor to the fleet. Part of a diary survives kept by an anonymous tutor to a 15-year-old midshipman called Frederick Gilly cruising on board HMS Gibraltar enforcing the blockade off L’Orient in 1811. The tutor was catastrophically seasick but, like Coleridge, was entranced by the very things which most navy men would not bother to have noticed. Coleridge had gazed for hours at ‘the sails sometimes sunshiny, sometimes snowy: sometimes shade-coloured, sometimes dingy’. The tutor, despite his seasickness,

found a pleasure totally new and indescribable in attending to the execution of orders. What most attracted my notice was the silence which prevailed; not a word was spoke but by the officers commanding, which not only showed the fine order to which the ship’s company had been reduced, but also the alacrity with which everything might be done in case of emergency…

At 11 o’clock all the men are mustered and inspected at their divisions by the captain and officers. All hands are expected to appear dressed in clean linen and their best clothes, consisting in the summer of blue jackets and white trousers.

This is not the usual picture of the rough and ready, brutalised workforce of a British man-of-war, but this journal, naively enthusiastic as it might be, was written for no purpose but the tutor’s own. On Friday 9 August 1811, he recorded that

When several ships are in company it is a very interesting sight to observe the manner in which anything is conducted, as for instance getting under weigh, coming to anchor, loosing and furling sails etc. The signal is first of all given from the admiral’s or commodore’s ship and then all begin at the same time and there is no small emulation in making a display of smartness and discipline. If the command be given to furl sails, then the first lieutenant orders the bosun to ‘Pipe all hands to furl sails’. They then come on deck and wait for the word. In the meantime the midshipmen stationed in the tops take their places. The next word is ‘man the rigging’. This is obeyed by the men ascending the first ratlines of the shrouds and there staying till the lieutenant sings out ‘Away aloft’. When they have got into the tops they wait again for the last word, ‘Lay out and take in – reefs.’(According to the number of reefs out when the sails were loose.) The whole fleet acts with smartness and dispatch.

That too is what you must imagine on the morning of Trafalgar, as the logs laconically describe the evolutions of the fleet, responding to a shift in the wind by coming on to the other tack, ‘wearing ship’ by taking her stern through the wind, raising the topgallant yards as the wind drops and more sail is needed, shaking out the reefs in the topsails, setting the steering or studding sails with which to add the slightest extra fraction of a knot in the light airs, setting the royals above the topsails, for that little bit more, and then lowering the ships’ boats from the davits and towing them on long lines astern. In their cradles on deck, they would not only have interrupted the line of fire; a shot landing among them would have sprayed the deck with murderous splinters.

A ship, to a stranger a maze of complexity, is to a seaman the infinitely exact working out of a few basic principles. The hull combines two contradictory qualities: quickness through the water for the chase of the enemy; steadiness to provide a platform from which guns could be fired. Greater waterline length provided the first, greater beam the second. The profile of men-of-war, seen from bow or stern, was curved steeply in above the waterline because it was realised that if the guns on the upper decks could be brought nearer to the centreline of the ship, there would be less roll and for a higher proportion of the time the muzzles of the guns would be on target. Two ships alongside each other could be touching at the waterline but forty feet apart at the quarterdeck. The heaviest guns, which fired roundshot weighing 32 pounds each, enormous objects, 9ft 6in long and weighing very nearly three tons, were on the lowest decks, those above getting increasingly lighter, for the same reason. The keel of course was dead straight, made of vast baulks of elm, the bow extremely bluff, because there was more room aboard if the full width of the ship was carried as far forward as possible. The stern sharpened to a point, allowing the water to run smoothly off the lines of the ship, reducing drag. The very structure of their world was shaped to a purpose.

Everything in the hull was for strength. The frames or ribs of the ship were set in pairs along its full width, and carefully jointed so that no joint in any timber lay alongside a joint in another. It was a dense structure. If you stripped away the outer shell, the frames would still occupy two thirds of its outline. The whole structure was held together by iron bolts above the waterline and by bolts made of copper alloy below it. The hull was clenched into tightness. The underwater profile was sheathed in copper to keep it clean of weed, a form of anti-fouling and to deter the ship worm which destroys ship timbers in the tropics.

This immensely solid hull was then bridged internally with the heavy deck beams, huge oak timbers, each one placed beneath a gun, cambered slightly to meet the curve of the deck (cambered so that water would run off it) and fixed with grown-oak knees – cut from the curving part of a tree – which held the beams in place in both the vertical and horizontal plane. Over that was laid the deal deck planking, each plank two inches thick and 12 inches wide. The final element was the hull planking, several layers of it: particularly thick timbers known as wales fixed under each row of gunports, further thickening timbers above and below the wales, a mass of exterior planking, four inches thick, followed by interior planking of the same density, and on top of that, still further timbers known as riders and standards to give yet more internal strength. The construction method is more like that of a tank armoured in oak than a seagoing vessel. A first-rate ship like Victory might take ten years to construct. At their thickest, its walls would be three feet thick.

That was only the beginning: steering systems, capstans, anchors and pumps, the captain’s great cabin or in the greatest ships the admiral’s apartment, the galley, the sick room, the powder magazine – 42,000 lbs of gunpowder in 405 barrels aboard Victory – the water storage and the iron ballasting, the pens for the bullocks, pigs, chickens and sheep that were kept on board, the stores for bread, salt meat and the all-important lemons and limes (18,000 for one ship at a single loading) all had to be fitted out for this 850-man war machine to operate.

Above all that, of course, was the rig. Nothing looks more complicated or more idiosyncratic than the maze of lines, canvas and timber that stretch skyward above these ships. Victory is 186 feet long on her gundecks, 51 wide at her widest point. The poop is already 55 feet above the keel. The truck on the mainmast, the very highest point of the ship, is another 170 feet above that. Every cubic yard of space above those decks is put to work but in a system whose essence is clear and plain. There are three masts and each carries four square sails: the ‘course’ at the bottom – the mainsail, whose name means ‘the body’; the topsail above it, its name deriving from the time when it was simply the upper of two sails; the ‘topgallant’ above that, and above that the ‘royal’. The bowsprit, protruding 100 feet from the bow, carried four jibs. Between the fore and the mainmast and between the mainmast and the mizzen, still further fore-and-aft staysails – attached to the stays holding up the masts – could be set. Extra studding sails could be hoisted, attached to special booms run out on each side from the yards from which the usual sails hung.

In all, a ship like Victory could carry 40 sails, with about 1,000 blocks through which the rigging was led, the whole assemblage weighing about twenty tons and covering an area of more than two acres. Although no element of these extraordinary constructions would have been unfamiliar to anyone alive in 1805 – no special materials; nothing different in the hemp and canvas, iron and timber, blocks and pulleys from those found on land – the man-of-war, as complex as a clock, as large as a prison, as delicate as a kite, as strong as a fortress and as murderous as an army, was undoubtedly the most evolved single mechanism, with the most elaborate ordering of parts, the world had ever seen.

That was the striking fact. One witness after another described the overriding sensation they had on the morning of Trafalgar: the sense of beautiful order; the knowledge of preparedness; of the soundness of hull and spar; of standing and running rigging fully knotted and deeply spliced; of the rope work wormed, served and tarred; of the roundshot in their wooden cups stacked behind the great guns; of the powder cartridges ready far below, the crews in their allocated places; the weekly practice at gunnery known and understood.

The fleet itself, and each ship within it, just as much as a contemporary dockyard or factory, or even the new efficient prisons, was seen by all as an evolving and gyrating machine.

For every task, from getting up the anchor to unbending the sails, aloft and below, at the mess tub or in the hammock, each task has its man and each man his place. A ship contains a set of human machinery, in which every man is a wheel, a band, or a crank, all moving with wonderful regularity and precision to the will of the machinist – the all-powerful captain.

Late in September, on arriving back after a short rest in England, Nelson had written to the unsatisfactory and ailing Rear-Admiral John Knight in Gibraltar:

I was only twenty-five days, from dinner to dinner, absent from the Victory. In our several situations, my dear Admiral, we must all put our shoulders to the wheel, and make the great machine of the Fleet intrusted to our charge go on smoothly.

The phrase ‘great machine’ had a richer resonance in 1805 than it does today. The Newtonian universe was a machine. Beauty, as Newton had revealed, was systematic. The inter-locking, gyrating cogwheeled spheres of the orrery were a model of how things were. No one element could matter more than the system of which it was a part. The universe, in one part of the 18th-century mind, was a uniquely ordered affair, a smoothly clarified machine of exquisitely oiled parts, whose majesty consisted in its rationality. God, it had become clear, did not feel, intuit or imagine. He thought.

As a reflection of that, machines were what grandees loved to visit. The opening of the Albion Steam Mill in March 1786 on the south bank of the Thames in London had been accompanied by a grand masquerade. Dukes, lords and ladies flocked to it. Lords Auckland, Lansdowne and Penrhyn were given tours by Matthew Boulton the great steam machinist and entrepreneur. The East India Company directors were there, as was the President of the Royal Society. A distinguished French Académicien, the Marquis de Coulomb, was caught doing a little industrial espionage on the side. The machine then was still a model of what might be, the image of dynamic exactness, of un-deluded inventiveness harnessing natural forces, which not only mimicked the workings of the universe but stepped outside the limits which human muscle had always imposed on human enterprise.

That was at the heart of the machine’s allure: it was rational potency, an enlargement of the possibilities of life. When James Boswell had visited Birmingham in 1776, he made a beeline for the works belonging to Boulton at Soho. Boswell stood amazed at the scale and energy of the ‘Manufactory’ where 700 people were employed (almost exactly the number on a ship-of-the-line) and regretted that Dr Johnson was not there with him

for it was a scene which I should have been glad to contemplate by his light. The vastness and the contrivance of some of the machinery would have ‘matched his mighty mind’. I shall never forget Mr Bolton’s expression to me. ‘I sell here, sir, what all the world desires to have – POWER.’

It is an analogy that is everywhere in the navy. Lord Barham, First Lord of the Admiralty, a carping, wheedling, occasionally intemperate and unattractive man, who never hesitated to wag the finger, nor remind his superiors of the length, intensity and importance of his labours, who congratulated himself on ‘having naturally a methodical turn of mind’, saw his job simply as ‘keeping the engine moving’. As he wrote to Pitt on 22 May 1805, ‘I thought it right to lay these few ideas before you, that, if possible, the whole machine should be made to move a little brisker, so as to afford us some prospect of success. We may flatter ourselves, from what has passed, that our skill in the management of ships and the activity and bravery of our seamen will bear us out; it is a fallacy, which will manifest itself in a few months if we are not furnished with men for our ships.’

Work, business, the oiling of the machine, and the keeping of the wheels turning, the provision of men by the press gangs, of timber, tar, and flax, from America, the Baltic and the Far East: that was Barham’s task. In the making of its ropes, the Royal Navy was thought to consume 14,935 tons of hemp a year. For its sails 95,585 bolts of canvas were required. Barham ensured that teak-built battleships were commissioned in Bombay, and both light frigates and ships-of-the-line from the Russians in the White Sea in Archangel. Supplies of English oak were running desperately thin, as they were all over Europe. Large loads of central and eastern European oak, carted to Baltic ports and then trans-shipped to England, were found on arrival to be useless. The navy surveyors were told they ‘must cordially agree to substituting elm, fir, beech and any other timber for oak, where it can be used.’ England must be scoured, as Barham had written in a memo entitled Forethought and Preparation and ‘Country gentlemen, and others who have small quantities to sell must be canvassed.’ He was keen to show anyone who would listen ‘the advantages of forethought and preparation in every kind of business and more particularly in naval matters. By such means an enemy is overpowered before he can prepare himself.’ His task was ‘to take the whole business upon myself until the machine was set agoing.’ Whoever decides the disposition of forces ‘must be a perfect master of arrangement. Without this, he must be in continual perplexity.’

Orderliness was in the air. Over 200 English grammars had been published in the second half of the 18th century, by which the wild sprouts of the language were to be disciplined and trained. The water closet with a ball-cock to control the inrush of water into the cistern had been invented in 1778. Public hangings at Tyburn in the west end of London had been done away with in 1783. Branding of criminals had been abolished. The Ordnance Survey, by which every inch of the British Isles was to be precisely triangulated, surveyed and mapped, had been founded in 1793. Income tax had been imposed by Pitt for the first time in 1798. Deduction at source had followed two years later. The first National Census had been conducted in 1801. A year later Thomas Telford had spanned the Thames in one leap with the new London Bridge. In 1803 Luke Howard had named the clouds for the first time. The numbering of London houses became compulsory in 1805. In January 1806, on station off the coast of South America, Captain Francis Beaufort developed the first version of the Beaufort scale by which, ever since, wind has been calibrated in precise increments.

The entire value system of a figure such as Barham was based not on the Nelsonian virtues of dash, inspiration and the heroic but on understanding, reason, clarity and order. Barham’s cousin and predecessor at the Admiralty Lord Melville had declared that his purpose was ‘to know with perfect accuracy the real state of the British navy as it now stands, with reference as well to the immediate calls upon it, as with a view to its progressive improvement to meet future contingencies. It is my duty to communicate the result of my investigation, for the information of his Majesty and his confidential servants.’ Latinate, explicit, attentive, prospective, urgent: this language forms the essential bedrock on which the fleets of 1805, the victory at Trafalgar and the 19th-century idea of the English hero were all laid.

It was, at some intuitive level, an appreciation of the fleet which had penetrated deep into English national consciousness. The navy was beautiful, substantial, orderly and English. Wordsworth would stand on the Dorset shore and stare, as his sister Dorothy wrote to their brother, ‘at the West India fleet sailing in all its glory.’ William Cobbett, as a boy, had felt his entire sense of being shift into another plane when, in the 1770s,

from the top of Portsdown, I, for the first time, beheld the sea, and no sooner did I behold it than I wished to be a sailor. But it was not the sea alone that I saw: the grand fleet was riding at anchor at Spithead. I had heard of the wooden walls of Old England: I had formed my ideas of a ship, and of a fleet; but what I now beheld, so far surpassed what I had ever been able to form a conception of, that I stood lost between astonishment and admiration. I had heard talk of all the glorious deeds of our admirals and sailors [which] good and true Englishmen never fail to relate to their children about a hundred times a year. The sight of the fleet brought all these into my mind in confused order, it is true, but with irresistible force. My heart was inflated with national pride. The sailors were my countrymen; the fleet belonged to my country, and surely I had my part in it, and in all its honours…

The beauty and power which so struck the young Cobbett also lay behind the great sequence of sea-pieces which JMW Turner was painting in London in the first decade of the 19th century. To see them, thousands of people crowded every year into the 70-foot-long gallery the painter had attached to his house in Harley Street. He had opened it to the public for free, both to promote himself and as a service to the nation. In all of these early sea-paintings, again and again, the roughness of the sea, its turbulence and incipient anarchy, is set against the very opposite: the impassive, dark, stable shapes of the men-of-war anchored within it, the moment of solidity in a world of thrashing light, indifferent to anything which the sea, or trouble itself, could throw at them.

These works by the young Turner are the great English conservative images of the age. They are anti-Romantic pictures. Europe itself is in turmoil; the settled ways of things have been thrown into a stir; and at times alone, at times as the controlling node in a network of alliances across the continent, England, for the English, remains the bastion of reliability and strength. That is what the great black blocks of Turner’s ships embody. He rarely, in these years, paints the men-of-war in motion, let alone in action. That is not their role. They are the wooden walls, the irreducible strength of England standing impervious to the chaos which revolutionary France threatened from across the channel.

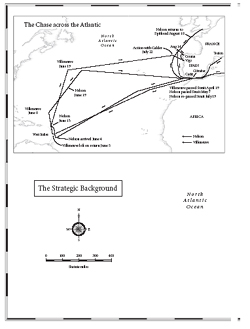

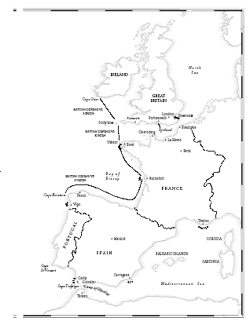

The fleet at Trafalgar represented fifteen per cent of the British armed strength at sea, no more than the fighting tip of an organisation spread across the whole of the eastern Atlantic. That was the deep and underlying order on which British defence relied. Lord Barham wrote to the King on the eve of Trafalgar describing ‘the present disposition of that part of your majesty’s fleet now in commission.’ The accumulated strength was rolled off with some pride: there were blockading fleets off French and Spanish ports, a home defence fleet in the Downs off the Kent coast, ships-of-the-line off Ireland and the Dutch coast, squadrons of frigates between Ireland and Brittany, between Brittany and the north Spanish coast, south along the Spanish coast to Capes St Vincent and Trafalgar, and on into the Mediterranean, some 180 ships-of-the-line in all and twice that number of frigates. Further ships, in port, were preparing to relieve those on station. Men were being pressed to man them, supplies imported to equip them.

Perhaps Barham, aware of the fragility of George III’s mind, was consciously portraying a situation of extraordinary coherence and regularity, evidence of Barham’s own foresight and preparedness over the previous 12 months. It was certainly, in this ideal form, a system designed to reassure a king. The task facing Barham was the same as the one that had faced British strategists for centuries. On the Atlantic shores of Europe, the British navy faced the French army. Strength in two different spheres confronted each other. It was a war, as Napoleon famously said, between an elephant and a whale. If France was to defeat her ancient enemy, she needed to invade England across the narrow seas of the Straits of Dover. In response, England needed to control those seas so as to prevent the invasion occurring. The single aim for British naval policy was to control the all-important access to the western approaches of the English Channel.

Napoleon wanted to destroy Britain, whose government was funding the continental alliances against him. ‘There are in Europe many good generals but they see too many things at once,’ he had said. ‘I see only one thing, namely the enemy’s main body. I try to crush it, confident that secondary matters will then settle themselves.’ The central matter was the invasion of England, or at least its destruction as a world power. ‘Bah!’ Marshal Masséna was said to have remarked years later when asked about the conquest of Britain. ‘Conquer it? No one even dreamt of it. It was just a question of ruining it; of leaving it in a condition that no one would even have wanted to possess it.’ Napoleon thought that once in England he could destroy it in three weeks: ‘Invade, enter London, wreck the shipyards and demolish the arsenals of Portsmouth and Plymouth.’ Then he could march on Vienna. His army for the task, when fully arrayed, stretched nine miles along the sands of Boulogne.

The heart of the problem for the French is that France has few good deep-water ports. Unlike England, which in the harbours of Falmouth, Plymouth and Portsmouth, and in the capacious anchorages of the Nore (in the estuary of the Medway, just south of the Thames) the Downs (just east of Dover) and Spithead (off the Isle of Wight) has room for several world-dominating battle-fleets; France on its Atlantic and Channel coasts has only Brest, and to a lesser extent Rochefort; and on its Mediterranean coast, Toulon. Extravagant attempts before the Revolution to construct a fleet-holding harbour at Cherbourg in Normandy had been abandoned for lack of money.

That geography had governed the naval strategy of the European powers throughout the 18th century. The British need was to pin the French inside their ports; the French to escape the blockades imposed upon them, unite and come in force to dominate the Channel where an invasion could be made. The line connecting Brest to Toulon, via the Strait of Gibraltar, was the battleground on which the naval contest between the great European powers was fought out. Cape Trafalgar is on that line, at one of its hinges, just west of the Strait of Gibraltar, and just south of the great southern Spanish port of Cadiz.

Those were the unchangeable facts. There were of course many more wings and complexities to them: the eastern Mediterranean and the role of the Turks and the Russians there; the position of Egypt as the gateway to India; in the North Sea the role of the Dutch and Danes, and of the Russians in the Baltic; the need for the British to protect Ireland on their Atlantic flank; the inviting vulnerability of the French and British possessions in the Caribbean; the power added to the French naval position by the Spanish coming into the war against the British in January 1805, adding – on the all-important Brest-Toulon route – the outstanding deep-water harbours at Vigo, Ferrol and Cadiz.

Despite those many added complexities, the essence of the strategic situation remained constant. The British Channel Fleet, under Admiral Cornwallis, held the French clamped into Brest; the British Mediterranean Fleet, commanded by Nelson, held the French clamped into Toulon. The third British fleet, commanded by Admiral Keith, and based at the Downs, controlled the Channel and the North Sea. The British had a lockhold on any French maritime ambitions.

Napoleon’s brilliantly lateral idea was to break open the British grip by applying to these maritime circumstances a strategy which he employed on land, with an unbroken string of profoundly bloody successes – he is thought to have been responsible for the death of some 1.5 million Frenchmen and uncounted others – over 30 times between 1796 and 1815. The manoeuvre sur la derrière was not his invention – it was the favoured method of Frederick the Great – but Napoleon made it his own.

There was nothing conservative about Napoleon’s attitude to war. Large ambitions involved high risks, and the essence of the risky Napoleonic plan, which went through many changes and permutations, was this: both the Toulon fleet under Villeneuve and the fleet at Rochefort on the French Atlantic coast, under Ganteaume, would slip out past the blockading British. That was quite possible: both had done it before. An easterly over the Atlantic coast of France would drive the British out to sea and allow the French in Rochefort to emerge. A northerly in Provence would have the same effect for the Toulon fleet. Villeneuve would make for the Strait of Gibraltar, the Spanish fleets at Cadiz and Cartagena would join him, the Rochefort squadron would drive south and west, and this huge accumulation of firepower – each man-of-war carried the weight of artillery that usually accompanied an entire land army – would be hidden in the immensities of the Atlantic Ocean. The rendezvous would be in the West Indies, from where they would return in force, gather more Spanish ships from Ferrol, push up to Brest, drive off the English Channel Fleet and with the French Brest fleet now accompanying them, would sweep the Channel (Napoleon’s phrase – balayer la Manche), push on to control the Straits of Dover and enable the invasion flotilla to cross.

The plan relied on the absorbent secrecy of the Atlantic and the desperate slowness of communications across it. The enemy could know nothing. He would be thrown back on to guesswork. A state of acute anxiety would be induced in him. There would be no telling where the French forces were, how they had dispersed or where they might recombine. Napoleon had hints published in the Moniteur, the government news organ, that India was the target, as it had been notionally in 1798. As he had done often enough on land, and was to do often again, the long trans-Atlantic feint to the Caribbean was to draw the defending forces out to it, leaving the main target – England itself – horribly exposed. The re-assembling fleets, in the plan Napoleon made, were to cut straight back from the Caribbean to the English Channel, and take up a position between the Straits of Dover and the British fleets pursuing them. Napoleon’s veterans, 150,000 of them, would pour across the Channel, England would be ruined and as Napoleon told his soldiers ‘six centuries of insult would be avenged and freedom would be given to the seas.’

Wellington thought that ‘The whole art of war consists in getting at what lies on the other side of the hill, or, in other words, in deciding what we do not know from what we do.’ Napoleon’s manoeuvre sur la derrière was the opposite of that: using the vastness of the ocean itself as a cloak (his term was ‘the curtain of manoeuvre’) behind which to concentrate his forces for the attack. The whole secret of Napoleonic war on land was the deceit and confusion brought about by dispersal, sudden appearance in the rear of the enemy, his flank turned, followed by rapid concentration and delivery of the blow. It is what he brought about in the Austerlitz campaign in the autumn of 1805 and it is what he planned for the Battle of the Atlantic too.

The account survives by Denis Decrès, the Minister of Marine, of the moment when he told Villeneuve of the scheme. It was in Boulogne in August 1804. ‘Sire,’ Decrès wrote to Napoleon, ‘Vice-Admiral Villeneuve and Rear-Admiral Missiessy [of the Brest fleet] are here. I have laid before the former the great project. Villeneuve listened to it coldly and remained silent for some moments. Then, with a very calm smile, he said to me “I expected something of that sort.” Going on, he said’ – quoting Racine –

Mais pour être approuvés,

De semblables projets ont besoin

d’être achevés.

‘To meet with approval, such plans need to have succeeded.’ It was a pivotal moment and a diagnostic remark: the French admiral, a product of the pre-revolutionary French royal navy, is not taken up by the blaze of inspiration in which the Napoleonic plan was conceived; nor rushes to salute the genius of the Emperor, but remains cautious, controlled, knowing and rational, the reaction of a practised and ordered mind. Nevertheless, and inevitably, the imperial vision prevailed. Villeneuve responded to the inducements dangled before him: once promoted vice-admiral and appointed Grand Officier of the Légion d’Honneur, he became, as Decrès described him, un homme tout nouveau. It was, Villeneuve had told Decrès, the prospect of glory which had changed his mind. He would ‘deliver himself entire’ to the project.

These were the sources of the drama that had then unfolded over the spring and summer of 1805: Napoleon’s radical military vision; a French navy out of sympathy with that vision (and a Spanish navy even more so) but doing the best to fulfil the imperial orders; the British Establishment and its naval servants intent on bringing the French fleet to battle. For all sides, it was a period of acute anxiety. If you read the file of correspondence received by the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty from the captains and flag officers who were part of the command structure of the Mediterranean Fleet in 1805, the beautifully organised pages are thick with worry and trouble, with the sense of incipient failure and inadequate resources, with the desperate mismatch between the sort of coherence which the tradition expected and the realities of sea and war.

Villeneuve broke out of Toulon on 30 March 1805 but in the persistent and disturbing fog of non- or partial-communication, Nelson missed him. His blockade had been set too loosely and Villeneuve escaped to the south along the Mediterranean coast of Spain. French spies in Paris got the news to London, where it soon appeared in the newspapers, with the added (true) detail that a combined French and Spanish fleet was bound for the West Indies. But it would take at least a month to get any such information to Nelson off Toulon. Within a week, Nelson heard that they had got out. But where to? For the best part of a month, Nelson failed to guess that Villeneuve and the Toulon fleet were heading for the Atlantic. Instead, he pursued him eastwards towards Egypt. Endlessly, besieged by worry, Nelson searched for him, or for news of him, desperate not to leave the eastern Mediterranean and Egypt unprotected, not even imagining the complexities of Napoleon’s Atlantic strategy. English agents in Madrid, Cadiz, Ferrol and Cartagena scurried for news, but to no avail. ‘I wish it were in my power to furnish you with more satisfactory intelligence,’ one of them wrote, ‘but the object of the Enemies Expeditions have been hitherto kept a profound Secret.’ Only on 16 April did Nelson hear that Villeneuve had been seen off the southeastern tip of Spain nine days earlier, and had probably passed through the Strait of Gibraltar the next day. Nelson was horrified: ‘If this account is true, much mischief may be apprehended. It kills me, the very thought.’

Other British officers, on guard along the peripheries of the European mainland, were equally susceptible to the possibility of failure destroying their careers. Any hint of inadequacy in battle was to invite a hailstorm of loathing from a well-informed public at home. Rear-Admiral Sir John Orde had been stationed off Cape Trafalgar with a small squadron as the French Mediterranean fleet joined Gravina with the Spanish from Cadiz and set off for the Caribbean. Hugely outnumbered, Orde had made no attempt to stop them. Summoned home, in disgrace, to strike his flag, he was never employed as an admiral again and was subject to virulent loathing from the public, particularly merchants in the City of London who considered their trade put at risk by his behaviour.

The possible rewards of naval life might have been huge, but the penalties – in public humiliation if nothing else – were appalling. Even when Nelson finally guessed and then heard the truth, it took weeks for his news to reach the Admiralty. Nelson’s dispatch written on 5 May from off Cape St Vincent, finally announcing that Villeneuve had left the Mediterranean, was received in London only on 3 June, more than two months after Villeneuve had left Toulon. Even then it was unclear if the French were headed for the Caribbean or Ireland. All Barham could do in London was station curtains of warships across the entire width of the western approaches of the English Channel, from Cape Clear in southwest Ireland, across to Scilly off Land’s End, to Ushant off the western tip of Brittany and then down to Rochefort and Cape Finisterre at the northwest tip of Spain. With an invisible enemy, the only possible option was to wait, armed and ready. This was the received strategy, but it was one based, essentially, on a condition of ignorance.

Added to the problems of a hidden enemy were the sheer uncertainties of navigation. Great improvements had been made in the course of the 18th century in the instruments and theories by which a ship could calculate its position at sea but still it was as much art as science. It was all very well to know the theory by which noon sun sights could establish your latitude, but they were no good when the sky remained cloudy for weeks at a time, and when maps and charts were far from the reliable documents they are today. The magnetic variation of the earth itself, which disrupts the workings of a ship’s compass differently in different parts of the ocean, could only be guessed at. The log lines, which measured a ship’s speed through the water, were often found to be inaccurately measured out and subject to wide operator error. Besides, all that such a line could measure was speed through the water. It could not take account of the many unknown currents in the sea by which speed over the ground was radically affected. Taking a log-line measurement when the weather was bad and the seas high was an exercise more in guesswork than in science. The navigator had to rely as much on a far older and more intuitive level of understanding of the sea – its colour, even its smell, the nature of the seabed which soundings brought up on the end of the lead line, or even the behaviour of seabirds. For a great deal of the time, Nelson’s fleet had to guess as much where they were as where the enemy was.

The strain told on everyone. Nelson finally left for the West Indies on 11 May. Villeneuve was now a month ahead of him. No one in England, despite the many varied reports about enemy fleets in Ireland, off Ferrol, approaching the Channel, had any idea where either Villeneuve or Nelson had got to. On passage, Nelson began to draft a plan of the battle he hoped for, encouraging his captains and their crews to race the French across the Atlantic, urging his ships to shave two weeks off the French fleet’s lead. On 4 June, he finally arrived in Carlisle Bay, Barbados and immediately wrote to William Marsden, Secretary of the Admiralty: ‘I am anxious in the extreme to get at their 18 sail of the line.’ It was, as Nelson calls it, ‘a laudable anxiety of mind’, but the nervous exhaustion is palpable. Letter after letter from the Caribbean is full of this urgency and worry: ‘My heart is almost broke,’ ‘the misery I am feeling’, ‘all is hurry’.

The French fleets failed to meet up in the Caribbean but Villeneuve, partly through some false information received by Nelson, kept one step ahead of him and on 5 June headed north and back for Europe. Nelson was exhausted, longing for home and England ‘to try and repair a very shattered Constitution.’ ‘My very shattered frame,’ he wrote to his friend and agent Alexander Davison, ‘will require rest, and that is all that I ask for.’ Not yet though. He had to set out back across the Atlantic, in pursuit of the French: ‘By carrying every Sail and using my utmost efforts I shall hope to close with them before they get to either Cadiz or Toulon to accomplish which most desirable object nothing shall be wanting on the part Sir of your most obedient servant. Nelson + Bronte’.

There is strain and exertion in every word. All he needed was proximity. Get close to them, and he felt he could rely on the destructive power of the fleet under his command. Every rag in every ship was hauled to the mast but he never caught them and never guessed at what the grand Napoleonic scheme might be. Villeneuve was heading, as his orders required, for Ferrol in northwest Spain, but Nelson was still thinking of the Mediterranean, and he headed for the Strait of Gibraltar. By 18 July, after a round trip of 6,686 miles, Cape Spartel, on the Moroccan side of the Strait, was sighted from the Victory, but no enemy in sight, ‘nor any information about them; how sorrowful this makes me, but I cannot help myself’. They had given him the slip.

Any complacent sense of system that might have prevailed among the armchairs of London was totally absent from the fleet. Throughout the anxious summer, the feeling at sea was of a desperate stretched thinness to the British naval resource. Admiral Knight at Gibraltar – something of a complainer – felt he had no ships with which to confront the Spanish in the Strait: ‘I therefore trust their Lordships will allow me to repeat to them the exposed situation of a British Admiral without the means of opposing this Host of armed Craft.’ In Malta, the pivot of the British presence in the eastern Mediterranean, Sir Alexander Ball, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge acting as his secretary, wrote in full anxiety on 24 June 1805. ‘We are in very great distress for Ships of war for the services of this island. Affairs here are drawing fast to a crisis.’ His ships were dispersed in Constantinople, Trieste and off Sardinia. He of course had no idea where Nelson’s fleet was, nor Villeneuve’s; or even whether England might have been invaded.

On 19 July, after very nearly two years at sea, Nelson stepped ashore in Gibraltar. The next day he was writing to the Admiralty, assuring their Lordships ‘that I am anxious to act as I think their Lordships would wish me, were I near enough to receive their orders. When I know something certain of the Enemys fleet I shall embrace their Lordships permission to return to England for a short time for the reestablishment of my health.’

If things had been different, the great events of 1805 might have reached their crisis at the end of July. Napoleon’s army was waiting at Boulogne. It was the most effective invasion force ever assembled and would go on to win the most devastating victories against the Austrians and the Russians at Ulm and Austerlitz. The strategy of the French Mediterranean fleet had foxed Nelson. It is true that the British Channel Fleet still held the French shut into Brest. All that was needed was for Villeneuve to collect the Spanish ships from Ferrol and the French squadron from Rochefort and to drive north to the Channel. The Brest fleet would emerge and in overwhelming numbers they would come to dominate the Channel as Napoleon had envisaged.

On 22 July, 100 miles west of Cape Finisterre, Villeneuve fell in with a British fleet under Sir Robert Calder and in fog and with a greasy swell sliding under them, met in an inconclusive battle for which Calder was pilloried in the British press. Nelson headed north from Gibraltar on 15 August. He left most of his ships with the Channel Fleet and in Victory went home to England, the arms of Emma Hamilton and rest. Any idea that the events of the preceding months had been governed by order and rationality would have summoned from him a hollow laugh. All was contingency, guesswork and desperation. He was reading in the newspapers, which he picked up from the Channel Fleet, of Calder’s half-hearted engagement off Finisterre. As he wrote to his friend Thomas Fremantle:

Who can, my dear Fremantle, command all the success which our Country may wish? We have fought together and therefore know well what it is. I have had the best disposed Fleet of friends, but who can say what will be the event of a Battle? And it most sincerely grieves me, that in any of the papers it should be insinuated that Lord Nelson should have done better. I should have fought the Enemy, so did my friend Calder; but who can say that he will be more successful than another?

Napoleon wrote to Villeneuve, to tell him that ‘the Destiny of France’ lay in his hands. After the action with Calder’s fleet, he went first into Vigo and then Coruña. He wrote to Decrès about the rotten condition of his fleet. The Bucentaure had been struck by lightning. His ships were floating hospitals. Masts, sails and rigging were inadequate. His captains were brave but inefficient. His fleet was in disorder. On 11 August, full of apprehension, he left Coruña, but two days later, frightened by false intelligence of a British fleet to the north, he gave the order to turn south. On 22 August he entered Cadiz, where he had remained ever since, sunk in shame. On the same day, Napoleon had written him a letter from the camp at Boulogne, addressed to Villeneuve in Brest, where he was expected to arrive at any minute.

Vice-Admiral, Make a start. Lose not a moment and come into the Channel, bringing our united squadrons, and England is ours. We are all ready; everything is embarked. Be here but for twenty-four hours and all is ended.

Villeneuve failed the test of nerve which Napoleon had set him, but he failed it on rational grounds. His inadequate fleet would have been smashed by the sea-hardened ships of the British Channel Fleet and of Nelson’s Mediterranean Fleet which were waiting for him off the Breton coast. Trafalgar would have occurred in August 1805, a thousand miles further north and the British would for ever after have celebrated the great victory of Ushant.

As it was, Villeneuve and his 33 ships were now shut into Cadiz by the small English squadron of between four and six ships-of-the-line under Collingwood, which had been cruising off the port since June. For months, they had been craning their ears to discover what was going on in Cadiz. And even now, reinforced on 30 August by Sir Robert Calder with 19 sail-of-the-line, there was no sense of the anxiety being over. Far from it. Fishing boats were stopped and boarded. Neutral American merchantmen were searched and their captains interrogated. Among the papers of Captain Bayntun of the Leviathan is the Atlas Maritimo de España, published in Madrid 1789, in its handmade sailcoth cover, sewn by a sailor on the Leviathan, and many of the pages deeply water-stained. The chart of Cadiz Bay is covered in Bayntun’s notes and lines, the anxious care of a blockading captain drawing in the bearings on the church at Chipion near St Lucar and the Cadiz lighthouse, working out the leading marks and the bearings on various fortifications around the city, carefully annotating and translating the table of soundings for the sand, gravel, rock and mud shoals south of the city. Even 200 years later, in a muniment room in England, it is a document drenched in anxiety.

All year long they had listened to the gossip coming out of Cadiz and all of it was transmitted back to London. The Spanish fleet was watering and taking on provisions. Admiral Gravina had been appointed to command. The Spanish crews had received five months’ pay. It was now said that Villeneuve ‘was likely to lose his head for his conduct, and it was supposed he would be sent a prisoner to Paris.’ The Combined Fleet was reported bound to the Mediterranean. Couriers were seen leaving for Madrid and Paris at ten o’clock at night. Gravina was going to strike his flag, disgusted, the report said, with the conduct of the French.

In early September a spy somehow got to Collingwood a complete breakdown of the ships in Cadiz, including precise information on their captains and the number of guns per ship. On 19 September the entire Combined Fleet was said to be stored and complete with provisions, but in want of sailors. There followed ‘a general press on shore, and a strict search of French, and Spanish Deserters on board all the merchant Ships of every nation.’ Battle would soon follow.

In the British fleet, this constant vigilance and anxiety exacted its price. A Lieutenant Wharton, in HMS Bellerophon on station off Ushant with the Channel Fleet under Admiral Cornwallis, longs to go home. He has just heard that his father has died and his affairs are ‘in a very confused state’. He gives his request to his captain John Cooke, who sends it to the admiral, who sends it to the Admiralty. A minute in response, by Marsden, is written as usual on the corner of the letter: ‘The expence of the Service does not permit Lt Whartons request to be complied with.’ No relief; he must stick to the task.

On 18 August, Lieutenant Pasco, flag lieutenant on Victory, was suffering from rheumatism and ‘my weak state of health’. Pasco wrote to Hardy, Hardy to Nelson, and Nelson to the Admiralty requesting that Pasco go ashore. The doctor on the flagship, William Beatty, recommended 14 days ‘Country Air, Exercise and change of diet’. Captain Hardy himself had been ‘for many months afflicted with very severe rheumatic complaints attended with maciation and privation of rest and obstinately resisting the efficacy of medicine’, for which Beatty recommends

relaxation of some weeks, from the duties of Service, change of air, and Regimen, exercise on horseback, or in a carriage, together with the frequent use of the Tepid Bath.

Sir Richard Bickerton had ‘confirmed affection of the liver’; Rear-Admiral Lord Northesk wants to go home ‘having urgent business in England’; Captain Morrison of the Revenge wants to go home: ‘A Rupture of some years Standing has lately become worse. I do not find my Health equal to the Duties of my profession.’ Admiral Knight in Gibraltar had become too ill to do anything. On the Achille on 21 September, different officers were suffering from repeated liver pain and visceral obstruction, ulcered leg and consumption. Lieutenant Will Davies on Spartiate was suffering from ‘rapid Constitutional Decay, privation of appetite and general debility’.

By early October, John Wemyss, captain of the Royal Marines on board the Bellerophon wrote to his captain John Cooke:

Sir,

I beg leave to represent to you that Domestic Concerns of a most Urgent and particular Nature, render my immediate presence in England indispensably necessary to my private Interests, and induce me to request you would have the goodness to use your influence with the Commander in Chief, to permit me to proceed thither, either by appointing some Officer included in the late Promotion to serve on board the Bellerophon in my room, or granting me such leave of absence as his lordship may deem proper. From my situation on the List of Captains and having some time ago completed a Tour of Sea Duty, and not having during the last thirteen years troubled my Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty for an indulgence, I trust will, in his Lordships Conscience, have due weight –

I have the Honor to be

Your most Obedient and

Humble Servant

John Wemyss

Capt Royal Marines

A month and a half later, on 16 November, after Trafalgar had come and gone, when Cooke was dead and Wemyss recovering from a dreadful wound, Barham wrote baldly:

‘Aqunt Lord Collingwood that Capt Wemyss’s request cannot be complied with.’

The ships themselves were as worn as their officers. By early October, Nelson had returned from England to join the fleet off Cadiz. He sent a list to the Admiralty of the state in which he found the ships: Victory was fit for service; Canopus would be better docked before the winter; Spencer was fit for service, Superbe ‘must be docked for her movement’ – the shifting of timbers in heavy weather – Belleisle needs docking, Donegal ‘needs docking but not so much as Belleisle.’

The inefficiencies of men, ships and supplies, the annoyance with others, the conscious display to superiors, the squabbles about prizes, prize money and the sums due to flag officers who may or may not have been absent from the station, the tendency to disobey orders, the sheer illness and exhaustion of many of the officers under this strain, the extreme tautness of the naval screen stretched around the European periphery from the Baltic to the Aegean, the vast army ranged opposite the British coast at Boulogne, the threat to the British possessions in the Caribbean, the slowness of communications, which meant that a conversation could take three months, the overriding anxiety about where the enemy fleets and squadrons were and how they were to be prevented from achieving the concentration they need to establish superiority in the Channel: all of this is the human and technical reality underlying the idea of an orderly fleet which they all held as the model of perfection in their mind. Alert they listen all the time for the truth straining at the horizon to identify the ships they see. On 12 September, Collingwood wrote to the Admiralty: ‘The intelligence I get of the Enemy is vague, and sometimes contradictory.’ It reads at this distance like a plea for understanding.

There was undoubtedly high tension in the exactness. On the morning of Trafalgar, for the first time in his life, Nelson forgot to wear his sword; it was found in his quarters after the battle. All around him on the Victory, the anxiety was running at a high level. Nelson, Hardy and the frigate captains who were with them toured the various decks of the ship. Nelson urged the men not to fire unless they knew the shot would tell and ‘expressed himself highly satisfied with the arrangements.’ There were then discussions over the danger to Nelson himself. Hardy, Nelson’s secretary, the ship’s chaplain and others discussed the possibility of persuading Nelson to conceal the stars on his coat. None dared raise the question with him, as it was known with what contempt he would treat it. The great officer needed to maintain a heroic bearing. He should, in the aristocratic mould, ‘appear and be’, which meant that he should wear his stars.

Instead, Blackwood raised the question with the admiral as to which ship should lead his column into the battle. The first ship would take an immense quantity of fire. On tactical grounds alone, the flagship should not be exposed to such fire. Nelson loved and admired Blackwood and accepted his advice. The Téméraire was sailing abreast of the flagship, so close that Nelson thought he might shout instructions over to her, that she should go ahead of the Victory, to take the brunt of the Combined Fleet’s defence. But Captain Harvey of the Téméraire could not hear and so Blackwood was sent in one of Victory’s boats to deliver the orders. The Neptune, one ship further back, was given the same orders by flag signals.

The discussion is anxious, clipped, excited. Nelson’s subordinates scarcely dare approach him. Even as Blackwood is away, Nelson, without countermanding them, goes back on the orders and urges the Victory forward, asking Hardy to have still more sail set so that the Téméraire could not pass. Lieutenant John Yule, who was in command on the flagship’s forecastle, seeing that the starboard lower studding sail

was improperly set, caused it to be taken in for the purpose of setting it afresh. The instant this was done, Lord Nelson ran forward and rated the Lieutenant severely for having, as he supposed, begun to shorten sail without the Captain’s orders. The studding-sail was quickly replaced; and Victory, as the gallant chief intended, continued to lead the column.

That is not the action or behaviour of the calm man. A Calder or a Villeneuve might have done the orderly thing, and allowed the Téméraire and the Neptune to go ahead. But Nelson’s battle agitation was governing him. ‘Lord Nelson’s anxiety to close with the enemy became very apparent,’ Henry Blackwood wrote afterwards. That too is another reason that battle was longed for: as a place in which the anxiety was over, a place paradoxically of ultimate order and calm.