5

BOLDNESS

October 21st 1805

12 midday to 12.30 pm

Distance between fleets: 1 mile – Contact

Victory’s heading and speed: 104? at 3 knots

Boldness: the Power to speak or do what we intend,

before others, without fear or disorder

JOHN LOCKE, Essay on Human Understanding, 1695

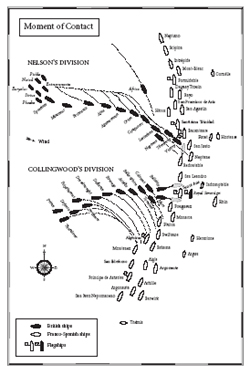

The more southerly of the two British columns, led by Collingwood in the Royal Sovereign, was nearer the enemy line and came within range first. The wind was still light, now more westerly and dropping fast, the sea smooth, the sun shining on the newly painted sides of the French and Spanish ships. As soon as the first shots of the French were fired, from the Fougueux, the flags on the British fleet were let fly. Jacks and ensigns were lashed to the fore topgallant stay, the main topmast stay and the mizzen shrouds, a multiplicity of signals so that in the battle, when in the still airs smoke would hang in thick clouds around them, friends would have a chance of recognising friends. The multiple flags were a sign both of comradeship and isolation. This was a battle in which all of them, jointly, would be alone.

At the Victory’s main topgallant masthead was ‘fast-belayed’ – not to be taken down unless a man was sent up there to untie it – Nelson’s signal No. 16: ‘Engage the enemy more closely.’ It remained there throughout, until shot away, less an instruction than a philosophy of battle: Touch and Take, the intimacy of violence. In the Spanish fleet, a large wooden cross was hung from the end of each spanker-boom, the wooden spar to which the foot of the sail behind the mizzenmast was bent. The large, highly visible crucifixes were, in that way, the mirror image of signal No. 16, an expression not of aggression but of hope and faith looming over every Spanish stern.

The Royal Sovereign was about two miles southeast of the Victory. Because of the speed given her by the smoothness of her newly coppered hull, she had stretched well ahead of the second ship in her own line, the Belleisle. She was strolling into hell: for perhaps twenty minutes she would be exposed to the fire of the enemy line; for perhaps another twenty minutes beyond that, before the Belleisle herself could come up, Collingwood’s flagship would be alone in the midst of the enemy. But he did not pause, nor in any way reduce sail. The fear was not of battle, nor of the French and Spanish gunners even then gauging the distance, but of the wind dropping, of the engagement going off at half cock and of the enemy fleet finding its way back into Cadiz before they were made to fight.

Besides, the sea-state was on the attackers’ side. Each long heavy swell coming in from the west was urging them on to battle. For the Combined Fleet, sailing north, the effect was very different: although their big, many-sailed rigs would in some ways have acted as a stabilising vane, each swell that came through rolled the ships heavily, through as much as ten or fifteen degrees each side, lifting first the port and then the starboard broadsides, so that only for a few seconds in every minute would the ship itself be level. The huge potential of the broadside armaments confronting the two columns of the approaching British fleet were, in these conditions, and at any distance, very nearly unaimable. The first shots fired at the British columns either fell short into the Atlantic or flew high over the top of their targets. Nor was aiming helped by a technical deficiency on the French and Spanish guns. British naval guns were by 1805 fitted with instant firing mechanisms: the moment the gun captain wanted the gun fired, he pulled a lanyard, a flintlock fell, the spark was communicated to the powder in the breech and the gun fired. In the French and Spanish ships, those flintlocks had not been fitted, and the gunners depended on a relatively slow-burning fuse, a slow-match, whose burning time could not be accurately predicted. In a rolling ship, that made target-selection a matter of almost pure chance. It can only have been in Nelson’s and Collingwood’s calculation that the pre-battle, the twenty-minute approach within range, would not signify. The battle that would count was the close-fought battle that was to follow.

The British took no unnecessary chances. On the Neptune, as one of her midshipmen remembered, ‘during the time we were going into action, and being raked by the enemy, the whole of the crew, with the exception of the officers, were made to lie flat on the deck, to secure them from the raking shots, some of which came in at the bows and went out at the stern.’ But the officers, however young, as an act of honour, as a sign of their status as gentlemen, were required to stand.

Paul Nicolas was a 16-year-old Lieutenant of Marines on the Belleisle:

The determined and resolute countenance of the weather-beaten sailors, here and there brightened by a smile of exultation, was well suited to the terrific appearance which they exhibited. Some were stripped to the waist; some had bared their necks and arms; others had tied a handkerchief round their heads; and all seemed eagerly to await the order to engage. My two brother officers and myself were stationed, with about thirty men at small arms, on the poop, on the front of which I was now standing. An awful silence prevailed in the ship, only interrupted by the commanding voice of Captain Hargood, ‘Steady! Starboard a little! Steady so!’ echoed by the Master directing the quartermasters at the wheel.

Whatever the perceived inadequacies of the enemy gunners, the sheer density of gunfire would ensure that the British columns were sailing into air filled with death and destruction. It was a moment of revelation at which the young Lieutenant Nicolas came to recognise what was expected of him:

Seeing that almost every one was lying down, I was half disposed to follow the example and several times stooped for the purpose, but – and I remember the impression well – a certain monitor seemed to whisper ‘Stand up and do not shrink from your duty.’ Turning round, my much esteemed and gallant senior fixed my attention; the serenity of his countenance and the composure with which he paced the deck, drove more than half my terrors away; and joining him I became somewhat infused with his spirit, which cheered me on to act the part it became me.

The instinct is to flee, or the next best thing, to hide behind the hammocks piled up in the netting on the bulwarks of the ship. But ‘a certain monitor’ – a Latinate, Enlightenment phrase for what an earlier more religious age would have called ‘conscience’ and a later, more psycho-analytical one the ‘super-ego’ – deflects him into the path of duty, which is revealed as a mixture of cool self-possession and in Nicolas’s extraordinary, half-theatrical, half-psychological language of ‘to act the part it became me.’ The echoes of Henry V are so deeply embedded they have become entirely unconscious: to act is now to act; fully to exist is to become the received role. Here, in these phrases, on the lip of extreme violence, can be seen the English hero in the making, a process whose roots go far back into English history.

The early 18th century had not liked the idea of a hero. A hero was unconformable; would not know about delicacy or even courtesy; and threatened rudeness. A hero would break the rules which it was the function of a civilised man to observe and sustain. Heroes were crude, whereas what was required was the polished and the developed. Sir Richard Steele, Gentleman Waiter to Prince George of Denmark, editor of the Spectator and one of the great arbiters of early 18th-century taste and understanding, discussed for his readers the most suitable paintings with which to decorate their apartments. ‘It is the great use of pictures,’ he instructed them,

to raise in our minds either agreeable ideas of our absent friends; or high images of ancient personages. But the latter design is, methinks, carried on in a very improper way; for to fill a room full of battle pieces, pompous histories of sieges, and a tall hero alone in a crowd of insignificant figures about him, is of no consequence to private men. But to place before our eyes great and illustrious men in those parts and circumstances of life wherein their behaviour may have an effect upon our minds; as being such as we partake with them merely as they were men; such as these I say, may be just and useful ornaments of an elegant apartment.

Heroism in the 18th century, in other words, was vulgar. It was not part of a system, as the third Earl of Shaftesbury described it, in which ‘We polish one another and rub off our corners and sides by a kind of amicable collision.’ Earlier society had been both stiff and violent. Modern civilisation was both supple and peaceful. Arrogant lords, illiterate squires, fanatical puritans and swashbuckling heroes were all in their own way angular rather than polished, and so were not to be embraced. People had to be taught how to be civilised and they could learn from a flood of books such as F. Nivelon’s, The Rudiments of Genteel Behaviour, published in 1737 to ‘distinguish the polite Gentleman from the rude Rustick’. ‘If at any times we must deal in extremes,’ John Toland had written in 1711, ‘then we prefer the quiet, good-natured hypocrite to the implacable, turbulent zealot of any kind. In plain terms, we are not so fond of any set of notions, as to think them more important than the peace of society.’ It was better to lie than to be rude.

Anyone in the swim in mid-18th-century England accepted lying and hypocrisy as both a necessity and the norm. When, for example, in 1746 as a young naval lieutenant so far disappointed in his hopes for command, Lord Augustus Hervey made his way into the higher reaches of London society, looking for promotion, his own cynical savoir faire allowed him to understand its manners and mannerisms for what they were:

I went after dinner to the Duke of Grafton’s, where I found the Duke of Newcastle [Chancellor of the Exchequer] dined at a wedding dinner for Lady Caroline Fitzroy, married to Lord Petersham, Lord Harrington’s eldest son. [She would soon become famous as the Countess of Harrington, the most promiscuous flirt in London.] The Duke received me with all that civility ministers can put on, and with all that falseness natural to his Grace, and seemed astonished that I was not a Captain, when he was the very person in the year 1744 who prevented Lord Winchelsea giving me the Grampus sloop…I received the Duke’s carresses and flatteries as if I believed them good current coin

In response to this need for courtesy and delicacy, wide swathes of English 18th-century life became fragile and dainty, in a way that no age in England, before or since, has managed. It became possible, for the first and only time, for a perfectly serious man to attend ceremonies at court in ‘a lavender suit, the waistcoat embroidered with a little silver or of white silk work worked in the tambour, partridge silk stockings, gold buckles, ruffles and lace frill.’

Politeness became a kind of affliction. The Duke of Newcastle who had been so smooth with Hervey acquired the nickname ‘Permis’, as he prefaced every remark with the bogus-sycophantic phrase ‘Est-il permis?’ This was the man to whom half of England had themselves been crawling, hoping for preferment in church, court, government, army or navy. In some ways, natural human dignity had been sacrificed on the altar of a kind of rococo politeness. A letter addressed to Newcastle in January 1756 concluded:

That your grace will permit me to subscribe myself with the inviolable duty and attachment to your grace,

My Lord Duke

Your Grace’s

Most devoted

Most obliged

Most obedient

And ever faithfull

humble servant

W. SHARPE.

This was not a culture from which the heroic would emerge. Apartments described as Frenchified (the adjective would also become slang for ‘suffering from the clap’) and floored in light deal, lit by modern open glazed windows, were furnished not with the big old comfortable chairs of the late 17th and early 18th centuries but little light French chairs, fitted with little swivel wheels on their feet and decorated with French linen festoonings instead of the thick welty damasks which England had once loved. Tables were no longer solid and immovable. They had been replaced by delicate gilded ‘scuttling’ tables in front of what, as Horace Walpole described it, ‘they now call a fireplace, a little low dug hole surrounded by a slip of marble and what does that do for a man? It toasts his shins.’ No longer did England have the giant roaring holes in the side of the room in which half trees were burned for hours at a time.

Mrs Caroline Lybbe Powys, a distant relation of the Austens, visited the by-then ancient and untouched late-sixteenth interiors of Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire in 1757:

Of course it is antique and rendered extremely curious to the present age, as all the furniture is co-eval with the edifice. Our ancestors’ taste for substantialness in every piece makes us now smile; they too would, could they see our delicateness in the same articles, smile at us, and I am certain, if anyone was to compare three or four hundred years hence a chair from the dining room of Queen Elizabeth’s days and of the light French ones of George II, it would never be possible to suppose them to belong to the same race of people, as the one is altogether gigantic, the other quite Liliputian.

Acceptable behaviour had become toy-like and it was not long before the anti-heroic fashion for a delicate sensibility ran out of control. Manliness, or even the ability to survive, had in fact almost entirely deserted those who were suffering from the cult of sensibility. In the Abbey of St Peter and St Paul in Dorchester, there is this poignant epitaph to poor Sarah Fletcher who died in 1799 aged 29:

Reader!

If thou has a heart fam’d for

Tenderness and Pity, Contemplate this Spot.

In which are deposited the Remains

Of a Young Lady, whose artless Beauty,

Innocence of Mind, and gentle Manners,

Once obtained her the Love and

Esteem of all who knew her, But when

Nerves were too delicately spun to

Bear the rude Shakes and Jostlings

Which we meet in this transitory

World, Nature gave way; She sunk

And died a Martyr to Excessive

Sensibility.

Of course, the Cult of Courtesy and Feeling was, at least in part, thought ridiculous even as it was happening – Dr Johnson defined ‘Finesse’ in his 1755 Dictionary as ‘an unnecessary word which is creeping into the language’ – and never more than when subject to the unforgiving verdict of the Grub Street journalists. No figure loomed more symbolically over the naval mythology of the 18th century than Admiral John Byng. Among navy men, he stood as an example of the honourable naval officer who had been betrayed by a combination of deceitful politicians and a crude, vengeful mob. He had been sent to the Mediterranean with a fleet that was inadequate in size, inadequately manned and inadequately equipped. His task was to relieve the siege which the French were laying to the British garrison in Minorca. On May 20 1755, he engaged their fleet under Admiral de la Galissonière, with the sort of inconclusive results which 18th-century naval battle often produced. His own leading ships were severely mauled by the French; de La Galissonière had adroitly withdrawn to leeward when it looked as if Byng was about to attack him with the centre and rear of the British fleet and Byng soon decided to withdraw himself to the safety of Gibraltar.

Every aspect of what he did, given his inadequate force, had been perfectly reasonable, without being in any way heroic, but as a result the Mediterranean base of Minorca had been lost by the British. The government ministers did their best to blame Byng and the English broadsheet writers rubbed their hands with pleasure. Byng was a gent, not a fighter, and as a result of the popular clamour against him, abetted by the astonishingly corrupt desire among ministers for self-preservation, he was famously shot for cowardice,

And, in Voltaire’s famous words, to encourage the others. His death was intended to satisfy a widespread demand for aggressive leadership, not among the cultured and political élite, but among the non-enfranchised populace. At that level, throughout the 18th century, another vision of admirable behaviour persisted. The mob did not want the smooth, conformable man, the slick hypocrite who could so politely manoeuvre his way into the rewards of high politics and high society. They wanted his very opposite, the clever thief, the man who thrived not by using the well oiled wheels of society, but by opposing them and cheating them, by attending only to the wellbeing of his own heroic self. The notion of the hero – alive in England in the 17th century and again in the 19th – had gone underground in the 18th century and flourished there as the criminal king, full of daring, guile, violence when needed, and a flamboyant theatricality, which emerged nowhere more entrancingly than when on the way to the gallows. For conservative supporters of the status quo, such as Henry Fielding, the novelist and magistrate, nothing was more subversive of that order than the behaviour of the show-off thief as he was taken to his judicial execution at Tyburn. The crowd views him as a ‘hero’ dressed in ‘imaginary glory’. He is puffed up with ‘Pride’ and ‘passion’.

The day appointed by law for the thief’s shame is the day of glory in his own opinion. His procession to Tyburn and his last moments there, are all triumphant; attended with the compassion of the meek and the tender-hearted, and with the applause and the admiration and envy of all the bold and hardened. His behaviour in his recent condition, not the crimes, how atrocious soever, which brought him to it, are the subject of contemplation. And if he hath sense enough to temper his boldness with any degree of decency, his death is spoken of by many with honour, by most with pity, and by all with approbation.

This extraordinary passage, written by Fielding in 1751, part of his Inquiry into the Cause of the Late Increase in Robbers, might be the template on which the heroic figure of Nelson himself was based. Every single keyword and key phrase of the Nelsonian amalgam is there: hero, pride, passion, ‘the day of glory’, ‘his last moments’, ‘triumphant’, ‘the compassion of the meek and the tender-hearted’, ‘applause’, ‘admiration’, ‘envy of all the bold and hardened,’ ‘his death spoken of by many with honour, by most with pity, and by all with approbation.’ It is as if, half a century before, the appetite was there among the mob in the streets en route to Tyburn for the kind of figure which Nelson would provide them in the late 1790s and early 1800s. The public figure of Nelson is modelled not on the Newcastle-Byng template, the big, solid, respectable, prudent and lying establishment, but on the bold, brave, tricky, clever, daring, nimble-minded and nimble-fingered, counter-culture hero of the thief.

The appetite for such a hero was certainly there, but the 18th-century cult of gentlemanly courtesy could not satisfy it. It was fed by a stream of twopenny broadsheets and sixpenny pamphlets, filled with journalistic accounts of criminals in Newgate prison in London. For sale singly or bound in collections for a shilling, by 1760 almost 1,300 of these Newgate prison lives had been published. Men of charm, wit, honour, violence and great professional skill, with a protean ability to appear and disappear, with no social standing, money or education, alert for captures, prizes and victories, ready to risk all for the glory of their triumphs: more connects the image of the naval hero and the thief than divides them. There is, in other words, something in the national hero of 1805 which looks like an adopted and legitimised criminality. Nelson and his band of brothers might be seen as a set of sanctioned villains, living lives that oscillated between intense risk and predatory gain, a role in which a deeply prepared public consciousness welcomed and adored them. And in that role, distinguishing them from the stiff establishment figures with whom the populace in general felt little sympathy, two qualities were central: daring and sincerity.

By 1805, the femininity of the mid-18th century was being left behind. Exaggerated sensibility had started to look absurd. Clothes, for both men and women, had become sober and simple. Their colours were plain; embroidery had shrunk to a minimum. The wig and hair powder had both been dispensed with and men wore their own hair unpowdered, either short in the Roman style or longer and romantically wayward. There is at least some evidence that portrait painters, including Sir William Beechey, when painting Nelson, fluffed up his rather flat reddish-grey hair into much more of a heroic creation than it was. The hero needed big hair. The same treatment was given by Sir Thomas Lawrence to Wellington, whose real hair, as painted by Goya, was insignificant and mousy. In Lawrence’s version, Wellington looks as if he has just emerged from the salon into a fresh breeze, the correct setting for a hero. The admirable had moved outside.

A fashion for manliness had begun to take over the culture. You can see it happening before your eyes in Pride and Prejudice. Jane Austen had completed the original draft of the novel before 1800 and in it one can see dramatised the shift in values between the 18th and 19th centuries, arranged around the two potential heroes of the book: Mr Bingley and Mr Darcy. Mr Bingley is 18th-century man: handsome, young, agreeable, delightful, fond of dancing, gentlemanlike, pleasant, easy, unaffected and not entirely in control of his destiny. Darcy is fine, tall, handsome, noble, proud, forbidding, disagreeable and subject to no control but his own. It is a strikingly schematic division. Darcy is like a craggy black mountainside – Mrs Bennett calls him ‘horrid’, the word used to describe the pleasure to be derived from a harsh and sublime landscape; Mr Bingley is a verdant park with bubbling rills. Darcy is 19th-century man, manliness itself, uncompromising, dark and sexy. And it is Darcy, of course, whom the novel ends up loving. Darcy is the coming man, Bingley the old way of doing things. In some ways, Darcy is the template on which the severe and unbending model of Victorian manliness is founded.

The implication of the novel is that there is something better than politeness and that the merely civil is inadequate. Pride and self-possession, even to the extent of rudeness, taciturnity – ‘He does not rattle away’ – sudden unpredictable behaviour and abrupt judgements had become not a symptom of barbarism but of authenticity, of a truth to a more fiercely defined self which cannot tolerate the hypocrisy on which the previous century was founded. Darcy is ‘silent, grave, and indifferent’, words in this new moral universe which signal pure approval.

It is not difficult to see in this powerful and spreading ethic and aesthetic a version of the new economic reality. A society based on the fixed and ancient ranks, while dressing its aesthetic sense in patterns derived from the ancients, will like the idea of fixed perfectability, of a static order as the definition of beauty. But British society in 1805, in which the motor and generator of national life was increasingly commercial, a commercial empire and armed forces in which enormous prizes and high prestige could be won, was increasingly impatient with and contemptuous of the stupidities of rank. What mattered was authentic, self-generated worth. The first years of the 19th century were a surprisingly rude and frank moment. St Vincent, when First Lord of the Admiralty, could write to the Marquises of Salisbury and of Douglas in a way no one could have dreamed of doing even 20 years before. Both grandees had written to St Vincent, outraged that employees of theirs should have been taken by the press gang, and asking them to be released:

23rd June 1803

To the Marquis of Salisbury

If the Board was to give way to the numerous applications for the discharge of Seamen, the Fleet could never be manned. Let me entreat Your Lordship therefore not to listen to the representations which are made to you on this head.

23rd June 1803

To the Marquis of Douglas

The Peerage is become so numerous that if Noblemen grant their Badge and Livery for the sole purpose of protecting Men whose occupation is upon the water from the Impress, it will be impossible to man the Fleet.

With the increasing erosion of the élite by bourgeois culture, something of the street understanding of the hero-thief in the 1750s had become 1805 middle-class mainstream thinking. By the time of Trafalgar, England had not only been long subject to an expensive and threatening war. She was deep into the social transformations which a commercial revolution had worked, and had, as a result, become a more serious place: tense, anxious, interested in material facts. War and commerce had rubbed away the frivolities which a previous age had come to see as normal and natural. A new roughness and harshness was in the air. As Linda Colley has written, there was ‘a distinctively sturm-und-drang quality about British patrician life in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.’ William Pitt died at the age of forty-seven, a victim of incessant work and compensatory drinking. One minister after another committed suicide, most by cutting their throats. Nineteen members of parliament killed themselves between 1790 and 1820. More than twenty went mad. Both Russian and real roulette became the diversion of the moment. Duelling and gambling enjoyed a resurgence they had not known since the 17th century.

Delight in easy gradients had been replaced by a passion for suddenness. The sudden was integral to the sublime. As the young Burke had described it,

Whatever, either in sights or sounds, makes the transition from one extreme to the other easy, causes no terror, and consequently can be no cause of greatness. In everything sudden and unexpected, we are apt to start; that is, we have a perception of danger, and our nature rouses us to guard against it.

That rousing of the inner nature was the source of sublime pleasure, and the new delight in the ‘great’ feelings which suddenness produces had penetrated very deeply into English society. Throughout the summers of the 1790s, the British royal family spent their time at Weymouth on the Dorset coast. At night there was dancing and in the daytime expeditions into the Dorset countryside. Far more exciting, though, was sailing in the bay. A 74-gun ship-ofthe-line, the Magnificent and, faster and more fun, a frigate, the Southampton, stood by every day, one for royal protection, the other for royal pleasure. The favourite game was for the Magnificent and the Southampton to approach each other under full sail on opposite tacks, with a combined speed of twenty knots or even more and to rush past one another, almost brushing sides. At the moment of climax, when the gunports of the two ships were inches apart, the entire crew of the Magnificent would cheer the rapidly passing royals. The experience was said to have ‘had a charming effect on the whole party’ and at the end of the summer Captain Douglas of the Southampton was knighted.

There is a cluster of new ideas here: the beauty in sudden change; the admirableness of the man whose character is authentically his and stands out from his surroundings; the flaccid nature of the courteous quadrille; the possibility of the heroic in the sublime; the delight in roughness rather than high finish. Perhaps the most intriguing question about Trafalgar is how this deep transformation in sensibility and in the sense of what was valuable played itself out in the conduct of naval war.

Eighteenth-century naval war had been based on the line of battle and the line of battle was founded on two unavoidable facts: a ship is longer than it is broad; and it cannot always manoeuvre where required. Its most defended and its most aggressive aspects are along its length; the most vulnerable its bow and stern where there are no or few guns and the structure is weakest. The essential idea of the line of battle, first used by the English in 1653 against the Dutch, is that the fleet lines up bow to stern, and presents those long armed broadsides to the enemy. This arrangement protects individual ships from both the raking fire of an enemy firing from ahead or astern and the possibility of being outnumbered and ‘doubled’ – with an enemy on both sides. It also avoids the danger of friendly fire. Ships in line ahead cannot by mistake fire into each other, something which had often happened in the chaotic mêlées of the 16th and 17th centuries. The line of battle, in theory, combines the force of many ships into a single fighting instrument.

But it had its problems. It was most effective as a defensive posture: it minimised one’s own risk but it also minimised the potential of damage to the enemy. It was a flock or a shoal of fish, bristling with violence, but concerned to look after itself, hugging itself for protection. In attack, in ships which anyway could not sail closer than 67? to the wind, and only sailed happily with the wind on the quarter, it was cumbersome and stiff. The line had to sail at the speed of the slowest ship and to turn a line without ships losing position, creating dangerous gaps, could only be done slowly and steadily. The ballet of naval warfare was a stately business.

Until the 1780s, when new gun-training tackles were introduced to the British fleet, allowing guns to be trained 45? both ahead and abaft of the beam, the broadside could only be fired at 90? to the direction in which the ship was sailing. To bring the guns of a fleet to bear on a mobile enemy in shifting conditions of wind and sea, with the possibilities of gear failing, ships running into each other or falling off to leeward, was an extraordinarily demanding task, only rarely achieved with anything like conclusive effect. What is called ‘decisive action’ – in other words one ship battering another for long enough for its crew to be killed or its rig destroyed – usually required broadsides to be fired into the enemy for at least half an hour at a distance of no more than 200 yards, closer if possible. ‘Hailing distance’ was Nelson’s favoured range for the ideal moment at which to open fire.

Inevitably, by the mid-18th century, there was an element of stalemate to line-of-battle fighting. Admirals became concerned above all to preserve their forces to fight another day and not to allow their captains to expose themselves to danger. Exactness was all. Admiral Edward Vernon, in 1740, for example, ordered that ‘During the time of engagement every ship is to appoint a proper person to keep an eye upon the admiral and to observe signals.’ No free spirits there. Captains needed to obey. In some ways, the ethic and aesthetic of order, propriety and communality which shaped so much of mid-18th-century life, also dictated the behaviour of fleets, the mentality of admirals and the fighting instructions they issued.

Battle as a result remained something of a quadrille. Lord Augustus Hervey, watching from the quarterdeck of a frigate in Admiral Byng’s fleet as they manoeuvred against the French outside Port Mahon in Minorca, considered the ‘evolutions’ of the enemy ‘pretty and regular’. Even the terrifying Admiral Boscawen, known to his sailors as ‘Old Dreadnought’, who when woken as a young captain by the officer of the watch and asked what to do with two large Frenchmen then seen to be bearing down on them, asked famously, standing in his night shirt on the quarterdeck, ‘Do? Do? Damn ’em and fight ’em,’ – even this termagant could in 1759 (in written instructions they all carried on board) address his captains like a dancing master:

If at any time while we are engaged with the enemy, the admiral shall judge it proper to come to a closer engagement than at the distance we then are, he will hoist a red and white flag on the flagstaff at the main topmast-head, and fire a gun. Then every ship is to engage the enemy at the same distance the admiral does.

When I think the ship astern of me is at too great a distance, I will make it known to him by putting abroad a pennant at the cross-jack yard-arm, and keep it flying till he is in his station; and if he finds the ship astern of him is at a greater distance than he is from the [flagship] he shall make the same signal at the cross-jack yard-arm, and keep it flying till he thinks that the ship is at a proper distance, and so on to the rear of the line.

This insistence on orderliness and on the stately meeting of equally matched forces began to break down in the last quarter of the 18th century. One after another, leading admirals and naval theorists, looking for battle advantage, started to abandon the old sense of regularity as the underlying principle of the well-conducted battle. Roughness, imbalance, asymmetry, concentration on one part of the enemy, the breaking open of accepted norms: this, increasingly, became the intellectual pattern of British naval battle in the last part of the 18th century. Classical forms had started to take on Romantic intonations.

By 1780 a system of tactics had been developed in which the idea of crushing part of the enemy had replaced the earlier intention of coming alongside, fleet to fleet, and hoping for the best. A swift and vigorous attack had replaced the slow and watchful defensive. Above all, naval tacticians had come to realise that concentrating as much of the attacking force as possible on the rear of the enemy meant that a devastating victory could be achieved. The leading ships in the enemy’s van could do nothing to help their beleaguered rear, at least not quickly, and that period of advantage for the attacker would bring victory before any help arrived. Battle had moved over from something that had seemed essentially fair to an action which was founded on the idea of initial and shocking advantage. From a matter of regular beauty, it had become a question of the devastating sublime.

Three leading British admirals, Hawke, Rodney and Howe, were largely responsible for the change. All, despite their age, Hawke born in 1705, Rodney in 1719, Howe in 1726, stood outside the acceptable mid-century courteous norm. Hawke’s victory at Quiberon Bay during the Seven Years War in 1759 off the Breton coast, in a thrashingly wild northwesterly November gale, had broken all the rules. Hawke’s blockading squadron heard that the French Brest fleet was at sea and it was spotted by one of his scouts when 40 miles west of Belle Isle. They were making for shelter, hoping to avoid an engagement. Hawke made the signal ‘for the seven ships nearest to them to chase, and draw into a line of battle ahead of the Royal George [his flagship], and endeavour to stop them until the rest of the squadron should come up, who were also to form as they chased.’ Forming as they chase, pursuing a reluctant enemy on to a wild lee shore: there are pre-echoes here of Trafalgar.

Hawke had no reliable charts of the reef-strewn bay into which he pursued the French. He simply assumed the French themselves would avoid the rocks and shoals and followed them. He used the enemy as his pilot, chasing up behind them as the shore and the night both approached. Two French ships surrendered, two sank, two ran ashore and burnt, seven others ran ashore deliberately, of which four broke their backs. Another nine escaped either into the mouth of the Loire or southwards to Rochefort, where they spent the rest of the war, imprisoned behind the British blockade. It was a model of victory achieved through wild and unregulated pursuit.

Hawke gleams as a Nelsonian hero avant la lettre, but he had his heirs. Rodney was intemperate, a gambler, falling so deeply in debt that in the 1770s he had to escape to Paris for four years, a man famed for a dashing attack against the Spanish, on a lee shore, at night and in a storm, always quick to seize an opportunity, and far from polished. He had the habit of ‘making himself the theme of his own discourse. He talked much and freely upon every subject, concealed nothing in the course of conversation, regardless who were present, and dealt his censure as well as his praises with imprudent liberality. Through his whole life two passions – the love of women and of play – carried him into many excesses.’

For the first time, at the Battle of the Saints off St Lucia in 1782, this wild womanising gambler of an admiral took the shocking and unprecedented step of leading his fleet through the enemy to the other side, an action which won him the battle, ‘pulverising’ the French and turning the world of naval tactics upside down. To go through the enemy was to become British orthodoxy.

Where Rodney was garrulous, Howe was silent, ‘a man universally acknowledged to be unfeeling in his nature, ungracious in his manner and, upon all occasions, discovers a wonderful attachment to the dictates of his own perverse impenetrable disposition.’ His courage was famous – Horace Walpole described him as ‘undaunted as a rock and as silent’ – and his appearance forbidding, but ‘Black Dick’ was loved by both officers and the men of the lower deck. When the mutinies erupted in 1797, it was the aged Howe whom the supervising committee at Spithead chose as the one admiral they trusted and would deal with. These were the precursors, both of them heroes to the common man, on whom the daring, mould-breaking aspect of the Nelsonian method was based.

In Lord Howe’s signal book issued in 1790, there is an entirely new signal, applicable when the British fleet was on the attack either from upwind of the enemy or to leeward of them:

If, when having the weather-gage of the enemy, the admiral means to pass between the ships of their line for engaging them to leeward or, being to leeward, to pass between them for obtaining the weather-gage. N.B. – the different captains and commanders not being able to effect the specified intention in either case are at liberty to act as circumstances require.

Lines broken through and captains at liberty to act as circumstances require: the world of the orderly dance was over. In the next edition of the signal book, the degree of individual freedom for ships was enhanced still further. Howe included a signal which told the ships of the fleet: ‘To break through the enemy’s line in all parts where practicable, and engage on the other side.’ A manuscript note is added in the Admiralty copy of the signal book: ‘If a blue pennant is hoisted at the fore topmast-head, to break through the centre; if at the mizzen topmast-head, to break through the rear.’ In either case, the van is to be left to sail away ignored. At the Battle of the Saints, Rodney had led his fleet in line ahead through the enemy line. At the Glorious First of June in 1794, Howe instructed his captains to approach the enemy in line abreast, break through wherever they could and ‘for each ship to steer for, independently of each other, and engage respectively the ship opposed in situation to them in the enemy’s line.’

There is a deep historical and geographical pattern at work here. The essential disposition of British and French fleets over the whole of the 18th century was governed by geography and the prevailing winds. The strategic position of the British was to be out at sea, to windward, holding their blockading station to the west of the European mainland. Their leeward guns faced the French. The French, emerging from port, approached the British from downwind. Their windward guns faced the British. This essential historical structure had a shaping effect on the way in which each side engaged in battle. The British guns, brought down towards the surface of the sea by the heeling of the ships, were habitually aimed at the hulls of the enemy. The French guns, lifted by the heeling of the ships, were usually aimed at the rigging of the ships.

More significantly than that, the French had developed the habit during battle of slipping off to leeward, avoiding the decisive contact, dancing away in front of the British eyes, compelling the British ships to turn towards them and allowing the French to rake their enemy on the approach. The great innovation of the Howe method in particular was to slip through the gaps in the enemy to leeward and then to hold them between the mouths of the British guns and the wind, since a fleet to windward cannot slip away. It is seized in a murderous grasp, the coherence of the fleet broken into fragments over which the French admiral has no control. The Howe method, in other words, dared to recreate the mêlée which 150 years previously the invention of the line of battle had been designed to avoid. It is, like so much of what was happening in European consciousness at the time, a return to the primitive, to the essential brutal realities of battle in which deep and violent energies are released by dispensing with the carapace of courtliness which the 18th century had done so much to cultivate. It is, in a phrase, Romantic battle, in which, as tacticians describe it, there is ‘the utmost development of fire-surface’. It was the method by which a fleet could develop an overwhelming attack of the most violent kind. And it released the possibilities of heroism. This morning, off Trafalgar, Nelson made a signal to the fleet, expressing an intention which in all likelihood his captains had already assumed: he would break through the enemy line and engage them on their leeward side.

The battle which made Nelson famous, fought off Cape St Vincent in 1797, is an example of this thinking. Commanding the British fleet was Sir John Jervis, who would be created Earl St Vincent as a result of the victory. He surprised a scattered Spanish fleet off Cape St Vincent on the northern edge of the Bay of Cadiz. The by now familiar signal went up; ‘The admiral intends to pass through the enemy’s line.’ But Jervis then made a mistake, asking his fleet to ‘tack in succession’ meaning that they should follow him in a single line ahead through the enemy, pursuing in other words the Rodney tactic. Only Nelson grasped the mistake, which would have allowed the Spanish the time to get away. On his own initiative, Nelson in the Captain converted the order into a version of Howe’s method of attack: all turn for the enemy together, in line abreast, not an orderly file but a flock of aggression descending on the Spanish fleet. Followed by Collingwood, Nelson broke through the middle of the Spanish fleet, created the havoc he required, destroyed the Spanish admirals’ system of control and captured two ships in the process.

Fascinatingly, there is an account of this battle written by a Spanish observer, Don Domingo Perez de Grandallana, who identified the core of the new English fighting method:

An Englishman enters a naval action with the firm conviction that his duty is to hurt his enemies and help his friends and allies without looking out for directions in the midst of the fight; and while he thus clears his mind of all subsidiary distractions, he rests in confidence on the certainty that his comrades, actuated by the same principles as himself, will be bound by the sacred and priceless principle of mutual support.

Accordingly, both he and all his fellows fix their minds on acting with zeal and judgement upon the spur of the moment, and with the certainty that they will not be deserted. Experience shows, on the contrary, that a Frenchman or a Spaniard, working under a system which leans to formality and strict order being maintained in battle, has no feeling for mutual support, and goes into action with hesitation, preoccupied with the anxiety of seeing or hearing the commander-in-chief’s signals for such and such manoeuvres…

Thus they can never make up their minds to seize any favourable opportunity that may present itself. They are fettered by the strict rule to keep station, which is enforced upon them in both navies, and the usual result is that in one place ten of their ships may be firing on four, while in another four of their comrades may be receiving the fire of ten of the enemy. Worst of all they are denied the confidence inspired by mutual support, which is as surely maintained by the English as it is neglected by us, who will not learn from them.

In three acute paragraphs, de Grandallana, who by the time of Trafalgar had become head of the naval secretariat in Madrid, identified precisely the post-systematic nature of the British advantage. He understood it was a cultural and not a technical advantage; reliant on the notion of the ‘band of brothers’, of which he would not have heard; and intuitively grasping the power of the individual ‘emulation to excel’ with which the 18th century had coloured the English heart. This is not a description of Trafalgar; it explains, nevertheless, why Trafalgar was won.