6

VIOLENCE

October 21st, 1805

12.30 pm to 2.15 pm

War: the exercise of violence under sovereign command

against withstanders

SAMUEL JOHNSON, A Dictionary of the English Language, 1755

Every man stood in the quiet of terror and discipline waiting for the first noise of battle. When it came, it sounded, it was said, ‘like the tearing of sails, just over our heads.’ But nothing except the air was being torn: this was simply ‘the wind of the enemy’s shot’, a passage of metal at speed through air. If it passed close enough to you, it could, without touching, kill, merely with the shock of the pressure wave that a travelling projectile creates. Unblemished men would fall dead on the deck as the roundshot passed. Others, extraordinarily, found their clothes on fire. The level of noise grew to a pitch nothing else in life could match. Each ship trembled, deep into its frames and keel, with the reverberation of its own guns firing. The ship was a place of yelling, the guns roaring, the blocks and tackles with which they were hauled out through the gunports and manoeuvred to bear on the enemy, screaming and squealing like pigs on the point of slaughter. The noise of ingoing and outgoing fire could scarcely be distinguished. From within the lower decks of the ships, enemy shot could be heard striking on the hull and bouncing away, but all part of a maniacal frenzy of noise, ‘like some awfully tremendous thunder-storm, whose deafening roar is attended by incessant streaks of lightning, carrying death in every flash and strewing the ground with the victims of its wrath: only, in our case, the scene was rendered more horrible than that, by the presence of torrents of blood which dyed our decks.’

No account survives of the experience in detail of the gunfight at Trafalgar, but in its place can be put the words of a thirteen-year-old powder-monkey called Samuel Leech, who experienced a brutal frigate action in the 1812 war against the United States. Leech was a political radical, deeply distrustful of the violent methods of navy discipline and of the inadequacy of the officer class. Something of that political and social rage undoubtedly colours his account but does not entirely devalue it. About a third of the crew of his frigate was either killed or wounded in the action against a large American, armed with more and heavier guns. Here, in Leech’s words, almost uniquely is the atmosphere between decks in the days of sailing battle. It is a scene of unequivocal horror. The firing has already begun:

I was busily supplying my gun with powder, when I saw blood suddenly fly from the arm of a man stationed at our gun. I saw nothing strike him; the effect alone was visible; in an instant, the third lieutenant tied his handkerchief round the wounded arm, and sent the groaning wretch below to the surgeon.

In this, as in most battles, cause and effect seem scarcely to relate. The damage seems to emerge from the air itself.

The cries of the wounded now rang through all parts of the ship. These were carried to the cockpit as fast as they fell, while those more fortunate men, who were killed outright, were immediately thrown overboard. As I was stationed but a short distance from the main hatchway, I could catch a glance at all who were carried below. A glance was all I could indulge in, for the boys belonging to the guns next to mine were wounded in the early part of the action, and I had to spring with all my might to keep three or four guns supplied with cartridges. I saw two of these lads fall nearly together. One of them was struck in the leg by a large shot; he had to suffer amputation above the wound. The other had a grape or canister shot sent through his ankle. A stout Yorkshireman lifted him in his arms and hurried him to the cockpit. He had his foot cut off, and was thus made lame for life. Two of the boys stationed on the quarter deck were killed. They were both Portuguese. A man, who saw one of them killed, afterwards told me that his powder caught fire and burnt the flesh almost off his face. In this pitiable situation, the agonized boy lifted up both hands, as if imploring relief, when a passing shot instantly cut him in two.

I was an eye-witness to a sight equally revolting. A man named Aldrich had his hands cut off by a shot, and almost at the same moment he received another shot, which tore open his bowels in a terrible manner. As he fell, two or three men caught him in their arms, and, as he could not live, threw him overboard.

The sheer shambolic squalor of these battles is not to be underestimated. The ships were smeared with blood. The blood rolling to and fro across the deck painted patterns on the clean-scrubbed deal. Afterwards, large parts of the ships had to be repainted and each ship carried in its stores the paint necessary to efface the gore.

Nor were these single crises. The cannonading, or the ‘smart salute’ of the broadside, as 19th-century commentators on naval warfare often liked to call it, went on often for an hour or even more at a time. There was no quick solution to the destruction of men for the most part hidden within the walls of their floating wooden blockhouse. Down on the maindeck, manfully bringing his powder to the guns from the magazine, Leech saw death and wounding around him again and again.

One of the officers in my division also fell in my sight. He was a noble-hearted fellow, named Nan Kivell. A grape or canister shot struck him near the heart: exclaiming, ‘Oh! my God!’ he fell, and was carried below, where he shortly after died.

Grape and canister shot poured through the port-holes ‘like leaden rain’. The sound of the large shot striking the ship’s side was ‘like iron hail’. The whole body of the ship was shaken by their impact, a deep, groaning thudding. Even worse, when these 24lb or 32lb balls penetrated the hull, giant splinters, several feet long, would go spinning through the confined space of the gundecks, killing and maiming any bodies trying to inhabit what had become knife-filled air. A shot that came through the gunports was called ‘a slaughtering one’ and it usually killed or wounded the entire gun crew. The dead were then shoved out into the sea by the hole through which their death had come.

Men, in these circumstances, do not react, as one might imagine, with shrinking terror. There is a mindlessness to a battle of this intensity. What is repeated again and again, in all accounts of Trafalgar and other battles, is the cheering, ‘the deep roar of the outpoured and constantly reiterated ‘Hurra! Hurra! Hurra!’ They cheer each other on, filling with the noise of their own voices the space which terror might inhabit. Leech addresses the strangeness of that behaviour:

The battle went on. Our men kept cheering with all their might. I cheered with them, though I confess I scarcely knew for what. Certainly there was nothing very inspiriting in the aspect of things where I was stationed. So terrible had been the work of destruction round us, it was termed the slaughter-house. Not only had we had several boys and men killed or wounded, but several of the guns were disabled. The one I belonged to had a piece of the muzzle knocked out; and when the ship rolled, it struck a beam of the upper deck with such force as to become jammed and fixed in that position. A twenty-four-pound shot had also passed through the screen of the magazine, immediately over the orifice through which we passed our powder. The schoolmaster received a death wound. The brave boatswain, who came from the sick bay to the din of battle, was fastening a stopper on a back-stay which had been shot away, when his head was smashed to pieces by a cannon-ball; another man, going to complete the unfinished task, was also struck down. Another of our midshipmen also received a severe wound. A fellow named John, who, for some petty offence, had been sent on board as a punishment, was carried past me, wounded. I distinctly heard the large blood-drops fall pat, pat, pat, on the deck; his wounds were mortal. Even a poor goat, kept by the officers for her milk, did not escape the general carnage; her hind legs were shot off, and poor Nan was thrown overboard.

I have often been asked what were my feelings during this fight. I felt pretty much as I suppose every one does at such a time. That men are without thought when they stand amid the dying and the dead is too absurd an idea to be entertained a moment. We all appeared cheerful, but I know that many a serious thought ran through my mind: still, what could we do but keep up a semblance, at least, of animation? To run from our quarters would have been certain death from the hands of our own officers; to give way to gloom, or to show fear, would do no good, and might brand us with the name of cowards, and ensure certain defeat. Our only true philosophy, therefore, was to make the best of our situation by fighting bravely and cheerfully.

Although there is no direct evidence of coercion by British officers at Trafalgar, Leech distinctly heard one of the reasons that the men kept at their work on his frigate. ‘A few of the junior midshipmen were stationed below, on the berth deck, with orders, given in our hearing, to shoot any man who attempted to run from his quarters.’ It was a violent and unhappy ship but there were equally violent and disciplinarian captains at Trafalgar. The prospect of instantaneous execution by one’s own officers might well have persuaded the reluctant to fight longer and harder than they otherwise would. There is certainly evidence from Trafalgar of intense loathing between the lower and the quarterdecks. The seaman known as Jack Nastyface, on the Revenge, later told a grisly story:

We had a midshipman on board our ship of a wickedly mischievous disposition [a more serious accusation in early 19th-century English than nowadays], whose sole delight was to insult the feelings of the seamen, and furnish pretexts to get them punished. His conduct made every man’s life miserable that happened to be under his orders. He was a youth not more than twelve or thirteen years of age; but I have often seen him get on the carriage of a gun, call a man to him and kick him about the thighs and body, and with his fist would beat him about the head; and these, although prime seamen, at the same time dared not murmur. It was ordained however, by Providence, that his reign of terror and severity should not last; for during the engagement, he was killed on the quarter-deck by a grape shot, his body greatly mutilated, his entrails being driven and scattered against the larboard side; nor were there any lamentations for his fate! – No! for when it was known that he was killed, the general exclamation was, ‘Thank God, we are rid of the young tyrant.’

Here, then, is the amalgam of the British ship-of-the-line going into battle: on the quarter-deck and among the officers of the marines, an overwhelming sense of what needs to be done, of the ‘parts that became them’ in the drama of violence. Zeal, order, honour, love and daring were all aspects of duty, as was the steady doing of violence to the enemy. That is what Nelson’s signal to the men of England had meant. The officers are beautifully dressed, wearing silk stockings and shoes, not the seaboots most of them wore at sea, maintaining the upright stance of men indifferent to terror. Heroism for them was violence phlegmatically done. Collingwood, on the Royal Sovereign, as the shot flew around them, as his men were dying, carefully and elaborately folded up a studding sail, which was hanging over the starboard bulwarks, saying to his first lieutenant that they could not know when they might need it next. Watched by the Spaniards, they stored it away in one of the Royal Sovereign’s boats. On the Belleisle, as her great guns and those on the Fougueux dealt out to each other mutual and dreadful slaughter, Captain Harwood, walking on the quarterdeck, came across John Owen, who was his captain of marines, and offered to share with him a bunch of grapes. The two of them stood on the quarter-deck, watching the battle in which the Fougueux lost her mainmast and mizzenmast and the Belleisle lost all three, eating grapes, discussing the future.

Around them, on the decks below them and in the rigging above, the men, the people, were acting to different urges. For every £1,000 of prize money which a captain might expect to receive from a captured enemy vessel, the average seaman might receive £2 or £3. That is a measure not of a continuum between the two classes but a chasm, the two sorts of people occupying different mental worlds. The band of brothers did not include the men below. They were below physically, socially and conceptually and their reaction to this air thick with violence was the opposite of the stoical refined silence which honour imposed on the officers. The crews did not contain the tension but released it by pure aggression and bellowing, some of them even in mid-battle unable to resist poking their ‘heads through an idle port [to see the smoke] bursting forth from the many black iron mouths, and whirling rapidly in thick rings, till it swells into hills and mountains, through which the sharp red tongue of death darts flash after flash. The smoke slowly rolls upwards like a curtain, in awful beauty, and exhibits the glistening water and the hulls of the combatants beneath.’ That seaman, Charles Pemberton, later became a playwright. His memories, recollected in tranquillity, are coloured by a retrospective literariness in a way that Leech’s are not, but still his account of battle seems to describe an engagement with brutalism which is only rarely recorded from warfare but explains much of what happens during it. For Pemberton, quite explicitly battle is a moment of extreme and passionate violence:

Often we could not see for the smoke, whether we were firing at a foe or friend, and as to hearing, the noise of the guns had so completely made us deaf, that we were obliged to look only to the motions that were made. Sulphur and fire, agony, death and horror, are riding and revelling on the bosom of the sea; yet how gently, brightly playful is its face! To see and hear this! What a maddening of the brain it causes! Yet it is a delirium of joy, a very fury of delight!

There, in a rare moment of excess, some kind of truth is uttered. For those in the horror of battle, it is not horror but delight, a form of the sublime, a moment in which the collapse and disintegration around them, the excess of energy, finds sudden and explosive release in ‘a very fury of delight.’

Nelson wanted a conflict that was indescribable, not in the sense of moral revulsion, but as a plain narrative fact. The pell-mell battle, the anarchy in which the individual fighting energies of individual ships and men were released, could not submit to narrative convention. The fleets become their ships, the ships their men, the men their instincts. Decision-making moves from admirals to captains, to gun captains, to the powder-monkeys, the surgeons and their assistants buried in the bloody dark of their cockpits. Life – and death – in Nelsonian battle is atomised, broken into its constituent parts, made to rely not on the large scale manoeuvring of destructive force, but the will to kill and to live. Already, in the first moment of engagement, as Royal Sovereign entered the killing zone, that atomisation had begun. Every ship in all fleets considered that they fought Trafalgar almost entirely on their own. The literal fog of battle threw them in on themselves, a half-blind and in most places nearly fearless frenzy from which the British emerged victors and the French and Spanish destroyed. It was the chaos which Nelson required and which his daring approach had imposed on the enemy.

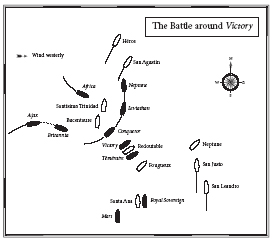

Trafalgar, nevertheless, can be seen to have three distinct phases: the first battle between Collingwood’s division and the rear of the Combined Fleet; the long-drawn-out mutual battering between Nelson’s division and the centre of the Combined Fleet; and finally, the battle between the van of the Combined Fleet, which had sailed away from the battle to start with, and a series of individual British ships which, very late in the battle, it had turned to attack. The two conflicting principles of war and of human organisation are apparent in all three phases: fragmentary British aggression, as if the British fleet were an explosive charge, breaking and scattering into tens of equally explosive pieces, coming up against the defensive wall of the Combined Fleet. That wall was inadequate because it was broken from the start, and the detonating elements of British aggression – the individual ships – found their way between the blocks of which it was made, so that their violence did not break like a wave against a seawall, but entered the body of the enemy’s defences and destroyed them from within.

The leading ships, of all three navies, knew that this was to be a tight, close-range affair. Spanish and French ships had prepared for the battle with grappling irons and extensive training in boarding the enemy which those irons held alongside. Grenades were prepared to be thrown down the enemy hatches from the tops of all three masts. The British had loaded their guns with two or even three shots each: ineffective at long range but delivering multiple killing and splinter-creating blows at short range. Every British ship, and several of the Combined Fleet, were armed with short range, large calibre, deck-mounted guns known as carronades, which were mounted not on a conventional gun carriage but on a pivot and swivel which would allow them to sweep the decks of enemy ships alongside. British crews were also provided with lengths of line, which once they had got deep among the mass of the enemy, they could use to lash the French and Spanish ships to their own, holding them there, not hundreds of yards away, not even a few feet away, but bound to each other, their hulls touching at water level, their yards and bowsprits tangled up high above, so that the enemy could not withdraw from the murderous onslaught of the broadsides which one after another were fired through them and into them. Close to, guns were loaded with reduced powder, to slow down the shot and ensure it remained within the hull of the enemy alongside and didn’t burst through to damage a friendly ship beyond it. Guns on high decks were aimed below the horizontal so that the shot would smash their way downwards through deck after deck. The big guns on the lowest tier were aimed upwards, so that in the enemy ship their shot would erupt through the decks beneath men’s feet, destroying men’s bodies from below. It is as if a boxer, with one hand, was holding the head of his opponent which, with his other, he then bludgeons into submission.

The intimacy of this battle meant that in some ships the muzzles of the French and English guns touched each other. An average British ship, like the Polyphemus, eighth behind the Royal Sovereign, expended 1,000 24lb shots and 900 18lb shots in the course of the battle, a weight equivalent to 18 tons of cast iron fired at a muzzle velocity capable of killing men and destroying masts at the range of a mile, but here fired into the faces of people six or eight feet away. In many ships, more than 7,000 lbs of gunpowder was used during the engagement. What is extraordinary is not that people died or that ship structures were savaged but that anyone or anything survived.

That story repeats itself again and again at Trafalgar, beginning at the moment that the Royal Sovereign broke into the Combined line. Collingwood had aimed just astern of the Santa Ana, who had backed her mizzen topsail to take the way off her. The British ship fired not a shot, apart from one or two to create a curtain of smoke around her, until her guns bore on the Spanish flagship. Collingwood had ordered his guns double-shotted and as they passed under the windows of the stern galleries, the huge, glazed glories of a ship-of-the-line, set in dazzlingly carved and gilded woodwork, the most theatrical, most honourable and in retrospect most absurd aspect of a ship-of-the-line, behind which admirals and captains had their cabins, and providing by far the weakest point in the entire structure, the Royal Sovereign gunners fired one by one, as their guns came to bear.

Any shot that entered through those galleries would travel the length of the ship on all three of its decks. No bulkheads or transverse timbers would interrupt their flight. They would slaughter without difficulty every creature, human and animal in their path. To achieve this longitudinal devastation of a ship – called since the mid-17th century a ‘raking’ – from a position in which no enemy broadside could be brought to bear, was the aim and the ideal of all late-18th-century ship tactics and the moment of the Royal Sovereign’s passing of the Santa Ana, achieved through Nelson’s daring perpendicular approach, was the apotheosis of the killing craft.

The Santa Ana carried a crew of some 800 officers, marines and men; 240 of them were killed or wounded in the first raking broadside from the Royal Sovereign. If Collingwood’s flagship was travelling at about 2 knots, gliding forward at a rate of about 3 feet a second – in the very light airs, both studding sails and the main-and fore-courses were shaken out; they wanted every bit of speed out of her they could – she would have taken almost exactly a minute to pass under the stern of the Santa Ana. That first minute of Trafalgar devastated the Spaniards, half of them recently swept up from the gutters of Cadiz. One Spaniard after the battle was found still to be in the Harlequin clothes he had been wearing when taken from the theatre where he had been entertaining the people of Cadiz. During this minute on the Santa Ana they were killed and wounded at a rate of nearly 4 men a second, a screaming, frenzied, terrifying minute, from which there would have been no escape, and in which the scenes between decks must have been beyond description.

On the long approach of the Royal Sovereign, they had scarcely managed to land a single shot on target. The cold silence of the approaching English guns, and the knowledge that this enemy, with such a ruthless reputation, was planning to pass under their desperately vulnerable stern – that can hardly have helped Spanish resolve. Now the Sovereign’s weight of metal plunged through her crew, totally disabling 14 of the Santa Ana’s guns, the full broadside of 50 guns fired once, half of them able to fire again. This was shock and awe. As Collingwood stood on the quarter-deck of his calmly advancing ship, he called out to his captain: ‘Rotherham, what would Nelson give to be here?’ There was delight in battle if battle was like this, in the supremely effective imposition of overwhelmingly damaging force. Two miles away to the northwest, Nelson watched through his telescope from the quarter-deck of Victory: ‘See how that noble fellow Collingwood carries his ship into action’. It was a form of battle he admired too.

At the same time, on the starboard side of the Royal Sovereign, the French Fougueux turned her port broadside on to the invading Englishman. On this side too, the Sovereign replied, her huge weight of iron slamming into the smaller Fougueux. Pierre Servaux was the master-at-arms on board:

She gave us a broadside from fifty-five guns and her carronades, belching out a storm of cannon shot, big and small, and musket-shot. I thought the Fougueux must be shattered, pulverised into tiny pieces. The storm of missiles that was driven against and through the hull on the port side made the ship heel to starboard. The larger part of the sails and the rigging was cut to pieces, while the upper deck was swept clear of most of the seamen who were working there and of the marksmen. On the gundecks below, there was less damage. There, not more than thirty men were put out of action. This preliminary greeting, rough and brutal as it was, did not dishearten our men. A well-maintained fire showed the Englishmen that we too had guns and could use them.

Servaux’s cool-headed account of that first blast of the iron wind from a British ship-of-the-line is revealing on several counts. There is, to begin with, the sheer volume of aggressive metal which the big three-decker can deliver. Initial shock, conveyed by hugely powerful ships at the head of the two columns, was central to Nelson’s scheme. It established a devastating advantage from which recovery was nearly impossible. But Servaux also makes clear two crucial facts about this form of attack. First, the effect of raking fire and the effect of a broadside received broadside-on is the difference between a battle and a slaughter. Raking fire, poured through the stern or bow of a ship, encountered no obstacle on its way. It met the vulnerable bodies of men and guns as violently as it had left the muzzles from which it had been fired. But gunfire which had to punch its way through the oak walls of the enemy ship could have no such effect. Its killing power was blunted by the density of the wooden defences. Even a broadside that drove the receiving ship over with the impact, as if caught in a vicious squall, did not disable a ship in the way that the Santa Ana was smashed by the raking fire on the Sovereign’s other broadside. Sailing skill, sheer deftness of manoeuvre and the alacrity with which crews would jump to instructions, either turning the ship into a position where it could rake its enemy, or turn itself away from raking fire, were the factors on which life or death depended.

Further than that, in Servaux’s words, the difference could not be clearer between the horror of exposure on the upper decks – the forecastle, the quarterdeck and the poop – and the relative safety of the oak-bulwarked gundecks below. Those upper decks were where the leading figures of the ship needed to be during the battle. Captains, first lieutenants, and masters were all to be found on the quarterdeck, boatswains, other petty officers and prime seamen on the forecastle, marine officers on the poop. These places were where the killing and wounding was done and so among these ranks, in ship after ship, the proportion of casualties often rose to well over a third or even a half. The more significant the man at Trafalgar, the more vulnerable he was.

These conditions were common to all sides, given the current technology. Why, one might ask, did the commanders not have constructed for themselves a quarterdeck shelter, in which they might be as protected from shot and musket-fire as those on the decks below them? Was self-exposure so central a part of the code of honour that a sailing ship-of-the-line, governed as these were, would not in fact have been operable in battle without it? It may be, at some subliminal level, that this self-sacrificial style of command also fed into the fighting capacity of ships. If his officers were prepared to expose themselves to so much danger, then what could a man do but follow their lead? It is precisely the opposite of generals commanding later battles from many tens of miles behind the front. Here the commanders placed themselves on the point of the spear.

It was not a complicated method, it was inherently bloody and it meant that officers needed to wait in the danger zone for long periods while the great guns did their work. That long period of exposure was an inescapable part of the theatre of battle. They had no protection, beyond the hammocks in their netting containers on either side of the quarterdeck, and the horizontal nets drawn taut above their heads to save them from falling debris. Neither was any use against roundshot, langridge or musket-fire. And the theatrical role played by honour, combined with the style of personal leadership Nelson had developed, meant that neither he nor any other officer could hide. Exposure of the person was more than an inherent hazard; it was an essential part of the task.

But there is one further and governing point which emerges from Pierre Servaux’s words: a deep, inbuilt sense of inferiority. They were not ‘disheartened’ by the brutal aggression. They could show the Englishmen that they had guns too. That is the language of defeat, of keeping one’s end up, of showing the better man that you are a man too. In that innermost, erosive doubt much of the outcome of Trafalgar is decided.

Collingwood was many minutes ahead of the next ship behind him, the Belleisle. Gathering to the aid of the Santa Ana, French and Spanish ships clustered like wasps around the intruder: the Fougueux raked the Royal Sovereign from astern; the San Leandro from ahead; the San Justo was cannonading her from 300 yards off her starboard bow; the Indomptable from off her starboard quarter. Shots were perfectly visible as they came towards the men on board, at least from the upper decks, and in these few minutes, so many were being fired at the Royal Sovereign that the crew frequently saw shots from different ships collide, or glance off each other, as if in a game of demonic aerial billiards. But the Royal Sovereign stuck to her guns. Once past the stern of the Santa Ana, Collingwood turned hard to port and ranged his ship right alongside the Spanish flagship.

Muzzle to muzzle for about two hours they fired man-killing shots into each other’s bellies. The British fired perhaps eighty broadsides in that time, the Spanish perhaps twenty-five or thirty. The aim was not to sink the other ship but to kill the other crew, or at least enough of them for their officers to consider any continuation hopeless, and those mathematics are the facts on which victory was founded. By about 2.15, the officers of the Santa Ana decided to surrender. Her starboard side, next to the Sovereign’s guns, had been ‘very nearly beaten in’ by the shot fired into it. Nearly all her officers were dead or wounded and they surrendered, as was the convention, by hauling down her flag. At almost the same moment, the mizzenmast on the Royal Sovereign collapsed, shot through by the fire of the five ships which had surrounded her. A few minutes later, the mainmast followed, leaving only the foremast standing, and that, as the expression of the time had it, ‘tottering and wounded’. Records and figures of dead and wounded on French and Spanish ships are sketchy, but on the British ships exact. There were 47 men dead on the Sovereign and 95 wounded, half of them severely, out of a ship’s company of about 600. The Spanish had inflicted casualties at a rate of about 25%; the British had probably killed or wounded about 50% of the enemy. That is the winning difference.

The Belleisle strode in after the Royal Sovereign, through the same gap Collingwood had entered, and the Belleisle again savaged the Santa Ana from astern, another double-shotted load with a canister of grape shot on top of them. These methods of warfare do not aim at individual destruction; they make environments murderous. The air between decks in a well-raked ship was as unsurvivable as any No-Man’s-Land over which machine guns played.

On all ships engaged in this form of brutal action, winning or losing, the damage was horrifying. ‘I now went below,’ Samuel Leech wrote of his encounter with a heavily armed American frigate in 1812, after his own outgunned ship had surrendered,

to see how matters appeared there. The first object I met was a man bearing a limb, which had just been detached from some suffering wretch. Pursuing my way to the ward-room, I necessarily passed through the steerage, which was strewed with the wounded: it was a sad spectacle, made more appalling by the groans and cries which rent the air. Some were groaning, others were swearing most bitterly, a few were praying, while those last arrived were begging most piteously to have their wounds dressed next. The surgeon and his mate were smeared with blood from head to foot: they looked more like butchers than doctors.

Here the sea was full of the bodies of scorched, butchered and mangled people. On board the defeated ships, the scene confronting the British officers was one of cinematic horror. A British midshipman went on board the Santísima Trinidad:

She had between 3 and 400 killed and wounded, her Beams where coverd with Blood, Brains, and pieces of Flesh, and the after part of her Decks with wounded, some without Legs and some without an Arm; what calamities War brings on, and what a number of Lives where put an end to on the 21st.

The companionway steps, leading down from deck to deck, were in the most brutalised ships so covered in blood that you could hardly walk on them without slipping. Nor is the sense of revulsion a modern reaction. ‘Such was the horror that filled’ the mind of the chaplain on board the Victory, the Rev. Dr Scott,

that it haunted him like a shocking dream for years afterwards. He never talked of it. Indeed the only record of a remark on the subject was one extorted from him by the inquiries of a friend, soon after his return home. The expression that escaped him at the moment was, ‘it was like a butcher’s shambles.’

Lieutenant William Ram of the Victory was brought down into the cockpit where the surgeons were working on the wounded. Ram was not aware as he was carried down below quite how desperate his condition was. The surgeon looked at him and the young man was told the seriousness of his wound.

On discovering it, he tore off with his own hand the ligatures that were being applied, and bled to death. Almost frenzied by the sight of this, Scott hurried wildly to the deck for relief, perfectly regardless of his own safety. He rushed up the companion-ladder, now slippery with gore, to the scene above [where] all was noise, confusion, and smoke.

On board the Leviathan,

a shot took off the arm of Thomas Main, when at his gun on the forecastle; his messmates kindly offered to assist him in going to the Surgeon; but he bluntly said, ‘I thank you stay where you are; you will do more good there:’ he then went down by himself to the cockpit. The Surgeon (who respected him) would willingly have attended him, in preference to others whose wounds were less alarming; but Main would not admit of it, saying ‘Avast, not until it come to my turn if you please.’ The Surgeon soon after amputated the shattered part of the arm, near the shoulder; during which, with great composure, smiling, and with a clear steady voice, he sang the whole of ‘Rule Britannia’.

A note survives on Thomas Main, written by his captain, Henry Bayntun, dated December 1st 1805, Plymouth:

I am sorry to inform you, that the above-mentioned fine fellow died since writing the above, At Gibraltar Hospital, of a fever he caught, when the stump of his arm was nearly well. H.B.

In an area of sea about one and a half miles long and half a mile wide, a series of individual ship-actions developed in which the brutal facts were laid out: if one ship in the encounter could kill more of the people on the other, the victory went to them. The ships of each fleet manoeuvred into contact with their enemy. Each attempted to find those positions ahead or astern from which they could inflict ultimate damage and have none or little done to them in return. It was like a wrestling match, close to and sweaty, in which each was looking to turn the other.

Astern of Collingwood, the Belleisle found herself embroiled with crowds of French and Spanish ships coming on to her as the rear of the Combined Fleet sailed up into the battle. The San Juan Nepomuceno, the Fougueux, the French Achille, the Aigle, the San Justo and the San Leandro and the French Neptune all attacked her one after another. Her masts fell in a vast tangle of rigging, sails and spars which blocked her gunports and prevented her from either manoeuvring or firing in her own defence. Only when ships in Collingwood’s column crowded into the same mêlée, was she saved from utter destruction. Of all the British ships, she was the most horrifically damaged. All three masts and bowsprit had been shot away. Her hull was ‘knocked almost to pieces’. The only place they could raise an ensign on board was on the end of pike held aloft. Without her rig above her, the body of the mauled Belleisle rolled like a hog in the swell. But here is a strange and significant fact. No ship in the British fleet should have been more murderously treated and yet, at the end of the battle, out of her crew of 750, only thirty-one of her men were dead and 93 wounded. Here too is one of the governing facts of Trafalgar. The captains and gunners of the Combined Fleet failed in the one essential: killing large numbers of the enemy.

The Polyphemus came to the Belleisle’s rescue, then the Defiance, the Tonnant and the Swiftsure. The crews of each ship cheered as the others came past and drove into the fighting. The Mars, miscalculating a manoeuvre, suddenly found herself stern on to the Monarca and the Algésiras and then bow-on to the Pluton. Captain Duff had allowed his ship to become caught in the most dangerous geometry which sailing battle could offer. It was then that a ball from the Pluton struck him on the chest, drove upwards, removed his head and left his trunk lying dead on the gangway just forward of the quarter-deck. The same shot scything through flesh, killed two seamen behind him. The men of the Mars gathered the trunk of their dead captain, held it up and gave three cheers ‘to show they were not discouraged by it, and they returned to their guns’. Duff’s first lieutenant, William Hennah, appalled at the death of a man he loved, instantly took over command. The ship then drifted out of the battle, all three of her masts still there but with not a single foot of standing rigging having survived the high-aimed and slashingly destructive fire that had been poured into her and killed and wounded 98 of her crew. If a single sail had been raised, the masts would have collapsed. In the ship’s log, her master Thomas Cook wrote, in words thicker with emotion than most logs allow for, ‘Poop and Quarter Deck almost destitute the carnage was so great.’ Even so, none of the ships of the Combined Fleet attempted to take either the Mars or the Belleisle, one of the failures which measures the gap in morale between the two fleets.

How do men sustain this behaviour? Certainly, the culture of violence had by 1805 entered very deeply into the thinking of the British naval officer. It is true that in his famous prayer on the morning of Trafalgar, Nelson had prayed for the greatest ‘humanity’ after the action, but humanity could only follow on from annihilation. Goodness depended on the riding and revelling. It is the paradox at the heart of moral war.

Sir Thomas Troubridge was not at Trafalgar but more strikingly than any other of Nelson’s captains he personifies qualities in the British naval officer of the early 19th century which were so excitedly engaged with violence that they seem to border on the unhinged. Apart from a fit of jealousy and a falling-out towards the end of Nelson’s life, Troubridge was always intimately close to Nelson. Nelson loved him as he loved others like him and did his best to promote him and reward him. They had been boys together on the Seahorse and as Nelson, favoured with better connections in the high echelons of naval command, outstripped him in his career, he ensured that Troubridge kept step. St Vincent singled Troubridge out, as he did Nelson, for the aggressive fighting qualities he recognised in both. Both Nelson and St Vincent admired Troubridge for his extraordinary courage in the 1794 mutiny at Spithead when he had seized ten of the mutineers himself. Nelson made sure that Troubridge, who through sheer bad luck drove his ship aground before the Battle of the Nile, nevertheless received a gold medal as the other captains had. He procured him a baronetcy and persuaded Ferdinand King of Sicily to give him jewels, a pension and boxes of gold coins. For Nelson, Troubridge was ‘My honoured acquaintance of twenty-five years, and the very best sea-officer in His Majesty’s service.’

In 1799, he was sent by Nelson to blockade the French in the city of Naples and to take the islands in the bay – Procida, Ischia and Capri – from the enemy. His task was ‘to extirpate the rebels’ who had risen against the authority of the Sicilian Majesties, with whom Nelson was then obsessed. On Ischia, Troubridge found priests preaching revolt against the Sicilian kings. Sir Thomas summoned a judge and then wrote to Nelson. The judge

talks of it being necessary to have a bishop to degrade the priests, before he can execute them. I told him to hang them first, and if he did not think the degradation of hanging sufficient I would piss on the d–d jacobins carcass, and recommended him to punish the principal traitors the moment he passed sentence, no mass, no confession, but immediate death, hell was the proper place for them.

In a separate letter he added, ‘If we could muster a few thousand good soldiers, what a glorious massacre we should have…’ and then apologised that he was unable to send on to Nelson the head of a Jacobin which he had been sent by a Sicilian loyalist but which Troubridge feared he could not forward to Nelson as the weather was too hot and the head would rot on passage.

Nelson went about the task of executing rebels with equal relish. As he wrote to Captain Edward Foote of the frigate Seahorse ‘the hanging of thirteen Jacobins gave us great pleasure: and the three priests [who had been sent to be degraded in Palermo] I hope return in the Aurora, to dangle on the tree best adapted to their weight of sins.’ Perhaps they were brutalising conditions, but the brutality found ready candidates in these men. Perhaps it was of a piece with the necessarily aggressive constitution of a successful military man. Nelson knew this about himself and knew the man he was. He was not smooth. This was, for him, quite explicitly, a war on terror. As he told Sir John Acton, the Neapolitan prime minister, republicanism ‘is the system of terror, by which terror the French hold all Italy.’ In those circumstances, ‘A fleet of British ships of war are the best negotiators in Europe; they always speak to be understood and generally gain their point.’ His aggression was part of the new ‘unpoliteness’ – a word used by Nelson in thanking the Lords of the Admiralty for sending ‘gentlemen to sea instead of dancing with nice white gloves.’ It is a phrase that marks him out as part of the great revolution against politeness which swept Europe at the end of the 18th century. When a certain Mr Hill attempted to blackmail him in 1803, by threatening to publish a true account of what had gone wrong during a desperately unsuccessful raid led by Nelson on the French flotilla outside Boulogne, Nelson responded with almost Shakespearean grandeur: ‘I have not been brought up in the school of fear,’ he wrote, ‘and therefore care not what you do. I defy you and your malice.’

St Vincent had said that ‘predatory war’ was Nelson’s métier and he was certainly capable of the kind of uncomplicated, direct, unelaborated violence in which predators specialise. When commander of the Boreas, he had flogged in 18 months 54 of his 122 seamen and 12 of his 20 marines, eight of them for mutinous language. He famously said he would be happy to hang a mutineer on Christmas Day and St Vincent’s final verdict on the greatest naval commander Britain has ever known was coldly evaluative: ‘the sole merit of Lord Nelson,’ the ancient earl wrote in a letter written deep into the 19th century, was ‘animal courage’.

This was undoubtedly one of the grounds on which the characters of Nelson and Troubridge met. It was, as so often with Nelson, a friendship charged with high passion. In January 1800 Troubridge had written to him warning him of the immorality of the Sicilian court – ‘We have characters, my lord, to lose; these people have none.’ – and of the dangers of being seen with Emma Hamilton gambling deep into the night. Nelson loved Emma and revered the Bourbon queen, at whom Troubridge had openly sneered, and wrote back to his junior captain a letter which has not survived but which was clearly smoking with rage and destruction. Troubridge replied:

It really has so unhinged me, that I am quite unmanned and crying. I would sooner forfeit my life, my everything, than be deemed ungrateful to an officer and friend I feel I owe so much to.

Only a few weeks later, in March that year, Troubridge wrote a letter to Nelson which takes the relish in death and violence to new heights. The British were besieging the French garrison in the port of Valetta on Malta. In attempting to escape, the Guillaume Tell had been taken by Henry Blackwood and others and four English deserters had been found on her, savagely wounded. Troubridge wrote to Nelson:

Two died of their wounds the other two are here one with both legs off & the other has lost his arm, a court martial is ordered, if they will but live Monday, they will be tried and meet their deserts immediately, we shot & hung a Maltese for carrying in two fowls

& tomorrow I hope will be gala day, for the old lady who I have long been wishing to hang, that carried in the intelligence. She swore she was with child, and possibly she will try some stout fellow: even then it will be good policy to destroy the breed.

What to make of such a series of statements? They are – almost technically in the last phrases – fascistic. They describe the scenes which Goya would paint in the Peninsular War a year or two later. They might be excused as coming from a man too long exposed to the facts of war, but they are words written in the expectation of approval from their recipient, bitter, dehumanising words which still shock at the distance of two centuries.

Perhaps the way to explain this is to see in Nelson the particular form of genius which is able to absorb contradictory qualities and to see no contradiction between them. He was an amalgamator, a bringer-together, a collector of qualities, an animator of spirits, an intuitionist, with a mind in which the rational and spontaneous, the instinctive and the systematic, and perhaps the violent and the loving were not strictly separable or distinct. As Coleridge said, no doubt repeating what he had heard from Sir Alexander Ball,

[Nelson] with easy hand collected, as it passed by him, whatever could add to his own stores, appropriated what he could assimilate, and levied subsidies of knowledge from all the accidents of social life and familiar intercourse. When the taper of his genius seemed extinguished, it was still surrounded by an inflammable atmosphere of its own, and rekindled at the first approach of light, and not seldom at a distance which made it seem to flame up self-revived.

That flickering and beautiful description of the workings of Nelson’s mind, as if it were partly a butterfly net, partly a chemical or electrical experiment, partly of the Enlightenment, partly of the Romantic world, has never been equalled. Nelson required, in his lieutenants, something of the violence of Troubridge. But he also valued its opposite. Few men in the navy could match the systematic and Olympian calm of Alexander Ball, a ‘tideless man’ as he was described at the time. ‘Courage,’ Ball once told Coleridge, ‘is the natural product of familiarity with danger.’ No sturm-und-drang there, just the Virgilian emergence of virtuous behaviour from the virtuous man. In 1797 he had saved Nelson’s ship, the Vanguard in a storm on a lee shore off the coast of Corsica, without even raising his voice. Ball had taken the Vanguard in tow but Nelson had, again according to Coleridge,

considered the case of his own ship as desperate, and that unless she was immediately left to her own fate, both vessels would inevitably be lost. He, therefore, with the generosity natural to him, repeatedly requested Captain Ball to let him loose; and on Captain Ball’s refusal, he became impetuous, and enforced his demand with passionate threats. Captain

Ball then himself took the speaking-trumpet, which the fury of the wind and waves rendered necessary, and with great solemnity and without the least disturbance of temper, called out in reply, ‘I feel confident that I can bring you in safe.’

But that neoclassical firmness of purpose in Ball (who also enjoyed a fearsome reputation as a disciplinarian) was not enough. It needed the addition of Troubridge’s troubled, violent and intemperate spirit. ‘Whenever I see a fellow look as if he was thinking,’ Troubridge said when asked how to impose discipline on a ship’s company, ‘I say that’s mutiny.’ Each man and each quality contradicts the other. They cannot tolerate each other. One looks like liberal civilisation; the other unprincipled barbarity; one is patrician (Ball’s father was a large landowner), the other of the street (Troubridge’s childhood had been poor); one is controlled, the other anarchic; but in battle neither is adequate without the other. Victory depends on their fusion, a melding of contradictory qualities. It is the contradiction between that grim controlled silence in the long approach to battle and the ruthless killing minute of the double-shotted broadsides pouring into the stern of the Santa Ana, tearing apart the flesh and bones of those within. They are twinned, the Apollonian and Dionysian aspects of war. Troubridge and Ball were Nelson’s closest fighting allies. Once, according to Coleridge,

when they were both present, on some allusion made to the loss of his arm, he replied, ‘Who shall dare tell me that I want an arm, when I have three right arms – this (putting forward his own) and Ball and

Troubridge?’

If Nelson was, as Byron described him, ‘Britannia’s God of War’, it was due to his intuitive understanding of the intimacy of violence, love, courage, honour, classlessness and victory. That was the amalgam which undoubtedly drew the mass of the ships’ companies at Trafalgar into their deep love and admiration of him. He was the conjuror of violence. As commander of the inshore squadron off Cadiz in the summer of 1797, already a vice-admiral, promoted after the battle of Cape St Vincent in February that year, Nelson and the great Thomas Fremantle had plunged off in his ten-oared barge, accompanied by Nelson’s boatswain John Sykes, to take part in the most dreadful, bloody slashing mêlée of his entire career. The British boats fought gunwale to gunwale with three Spanish gunboats which had come out from Cadiz. Boatswain Sykes twice saved Nelson’s life, at the cost of some terrible deep cutting wounds to his head, pushing himself between his admiral and his admiral’s death. Eighteen Spaniards had been killed out of about 26 and the rest wounded before they surrendered to this whirlwind of violence and aggression. In his dispatch Nelson, without affectation, put the name of Sykes the boatswain alongside those of Captains Miller and Fremantle, two of the gilded élite of the Navy. In Nelson’s own words, it was a moment at which ‘perhaps my personal courage was more conspicuous than at any other part of my life.’ Needless to say, the navy as a result, especially the seamen of the navy on whose level he had put himself, in precisely the way Alexander the Great used to put himself again and again into the bloody crux of battle, came to regard him with still greater awe, admiration and love. That is another way of expressing the amalgam: shared violence is the stimulus for the love on which the violence depends for its success.

This is the world of violence in which, as Wordsworth was writing in The Prelude during the summer of 1805, there was ‘A grandeur in the beatings of the heart,’ where ‘danger or desire’ made

The surface of the universal earth

With triumph, and delight, and hope, and fear,

Work like a sea…

Danger and desire, hope and fear, triumph and delight, violent exposure, removal from the ordinary, on the brink of destruction and self-destruction – this is the heartland of Romanticism, in which the immediate, the spontaneous, the intense and the primitive take over from anything more adult or known. As Coleridge wrote again and again in his notebooks ‘Extremes meet – Nothing & intensest absolutest Being’. Crisis is revelatory. In that, intensely contemporary with Trafalgar, are the seeds of the idea that battle is the place of ultimate reality, and the reason that Trafalgar came to occupy such an iconic place in the British imagination.