ORDER

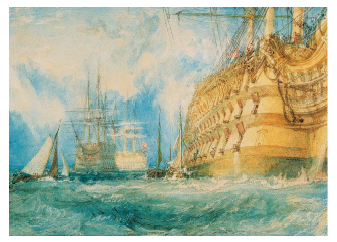

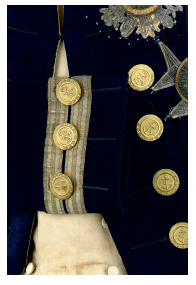

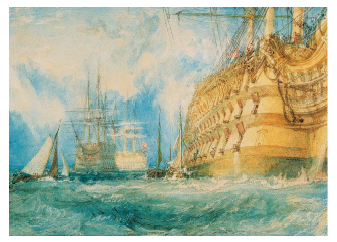

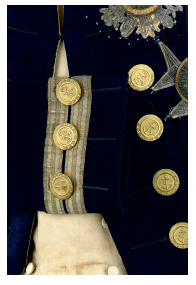

JMW Turner’s immense vision of the ships-of-the-line taking in stores (above) and the dignified richness of the naval officer’s working uniform –this (below) is the coat, with its gold distinction lace and Flag Officer’s buttons, in which Nelson was shot –are both founded on the conservative and Enlightenment virtues of strictness, substance and orderliness, all of them underpinning the workings of the Royal Navy and its

success at Trafalgar.

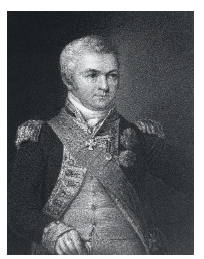

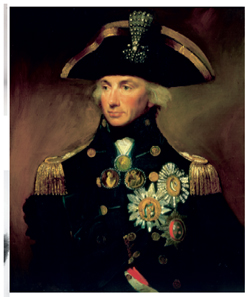

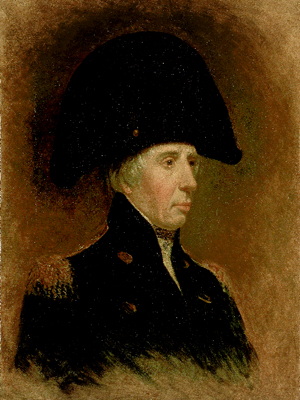

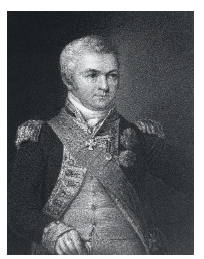

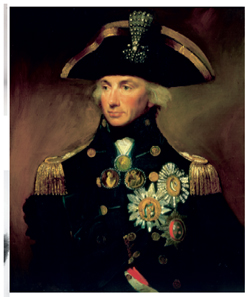

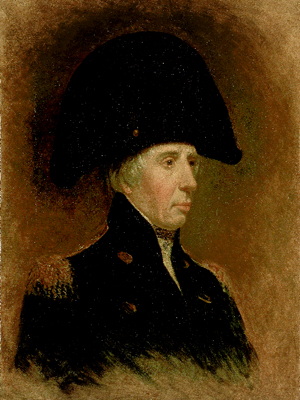

WHAT NELSON WAS NOT

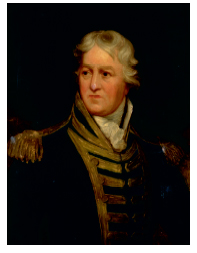

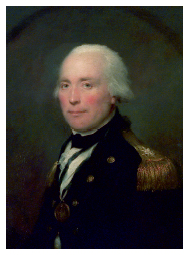

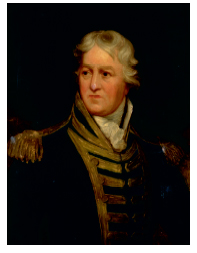

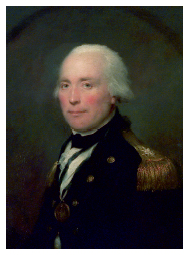

Admiral Sir Cloudisley Shovell (top) and Admiral John Byng (below) stand for the earlier tradition from which Nelsonian war set itself apart. Shovell, in armour, as was

usual for naval commanders until the early 18th century, and Byng, in acres of satin waistcoat, embody the patrician

and gentlemanly ideal of the civilised man at sea. Neither had the great Nelsonian quality: maritime competence combined with unbridled aggression. Shovell drove his entire fleet on to rocks in the Isles of Scilly in 1707, Byng was shot in 1757 for conducting too gentlemanly a battle with the French off Minorca.

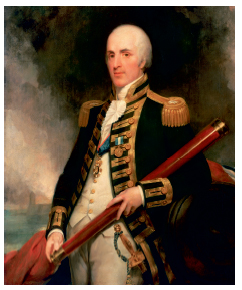

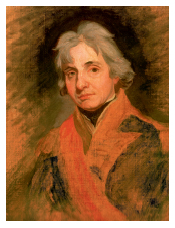

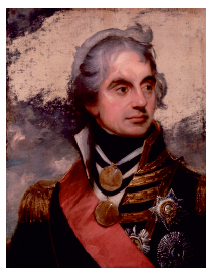

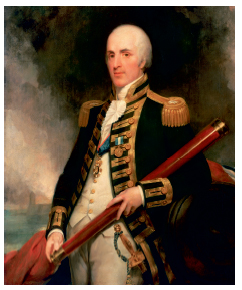

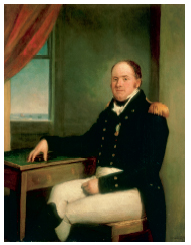

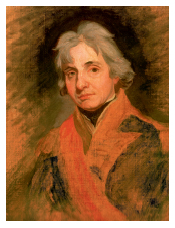

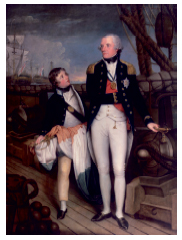

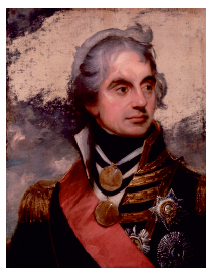

THE GREAT SUSTAINERS

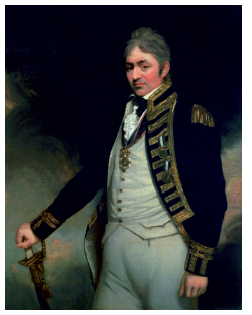

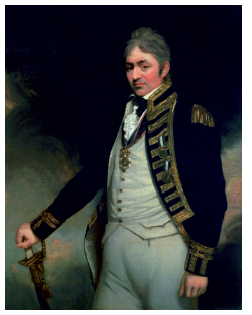

Lord St Vincent (above) and Lord Barham (below), both First

Lords of the Admiralty in the first years of the 19th century, brought different qualities to the task. As William Beechey’s magnificent head-on portrait of St Vincent shows, this was a fighting admiral, with a keen appreciation of Nelson’s ‘animal courage’, the will to win by which the 1805 Navy was fuelled. Barham, a longtime naval administrator, was a wheedling, finickety and irritatingly self-congratulatory man who nevertheless ensured

that the resources needed at Trafalgar were there and in time. It was this combination of qualities which ensured victory.

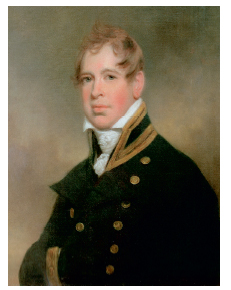

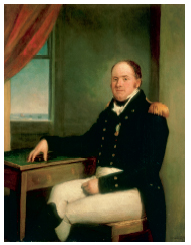

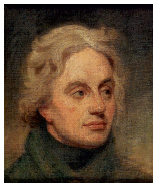

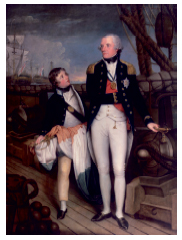

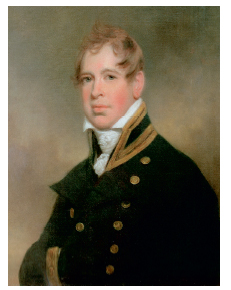

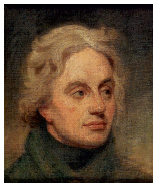

CAUTION AND AGGRESSION: A certain weakness hangs about the eyes of Sir Robert Calder, who failed to bring about a Nelsonian victory in July that year off Cape Finisterre and whose

career was ruined as a result.

Thomas Fremantle evinces the kind of bullish aggression which

endeared him to Nelson and allowed him to write a letter a week after Trafalgar regretting Nelson’s death

largely because it damaged his own career prospects.

SENSE AND SENSIBILITY: Sir Alexander Ball was Governor of Malta, hero of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, a figure of pure rationality, ‘a tideless man’.

The young William Beatty Surgeon on the

Victory, through his sensitive description of Nelson’s last hours, did more

to shape the inherited idea of Nelson than any other.

ELEGANCE AND BRUTALITY: Henry Blackwood was Nelson’s leading frigate Captain and admired by all, including his enemies, for the grace of his bearing.

Thomas Hardy, Nelson’s Flag Captain, was one of the harshest disciplinarians

in the fleet, who was nevertheless happy to kiss the dying Nelson twice.

VIOLENCE AND HUMANITY: Thomas Troubridge relished the doing of violence and the hanging

of criminals;

Henry Bayntun, who points to a chart of the battle and wears his victor’s sword and medal, did more than any other British Captain to save French and Spanish seamen in the storm that

followed.

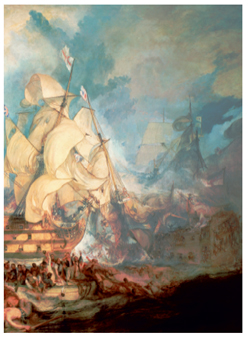

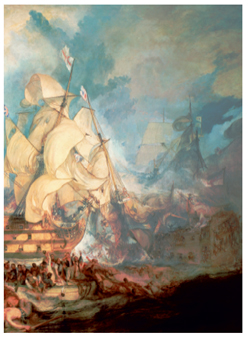

Beauty in the destruction of beauty, the heights and depths of sublime war: JMW Turner’s great image of The Battle of Trafalgar 21st October 1805 was painted for George IV in 1824. Victory’s foremast falls in a cloud of collapsing canvas; in the foreground men die and suffer.

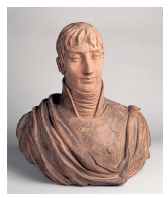

Even in the imagery by which they are recorded, the leading officers of the

Combined Fleet do not have the unity and cohesion of their British enemy.

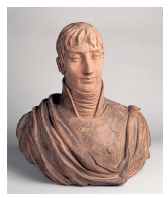

The French commander, Pierre Charles de Villeneuve remains the

pre-Revolutionary aristocrat.

Commodore Cosme de Churruca seem to

come from an earlier world altogether.

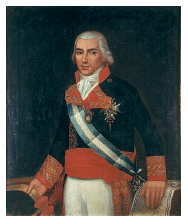

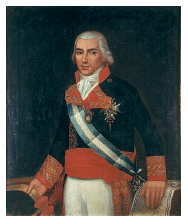

The Spanish Commander-in-Chief Federico Gravina and

his leading Captain

His leading captain, Jean-Jacques Etienne Lucas

of the Redoutable, stands the other side of that revolutionary

divide.

THE MULTIPLE MAN

In life, as in his portraits, Nelson flickered from one image to the next.

Lemuel Francis Abbott’s 1800 portrait is the ultimate in glamour,

the Prince of the Opera, the bejewelled and bemedalled hero.

The portraits by John Hoppner, done in about 1800, by William Beechey,

1801

And by Matthew Keymer in

the same year show a range

of delicacy, sensuousness and even exhaustion

which are quite absent from Abbott’s more famous, starry vision.

Hero-making in action. Guy Head’s meticulous and unheroic painting done in

1798-1799 can be set alongside William Beechey’s famous 1800 painting now on show in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

It is quite

obvious that Beechey has added an extra layer of more romantic and wayward

hair to the tightly controlled effect in the Guy Head portrait. If an age required

a hero, he needed hair and weather to match.

A painting of one of the bloodiest and riskiest moments in

Nelson’s life, attacking a Spanish launch off Cadiz in July 1797. The painting by Richard Westall was one

of a series made for the first biography of Nelson and it explicitly shows Nelson threatened with death by the

Spaniards and his own sword dripping with blood.

The Battle of Trafalgar, 21 October 1805: End of the Action painted by

Nicholas Pocock in 1808. This glamour-free portrayal of the last phase

of the battle was a favourite among naval men for its exactness and

reality. This is battle as dismantling yard, not the sublime vision of a

Turner, but a place of hideous mutilation and overwhelming destruction.

Two competing visions of the Death of Nelson, one

painted in 1806 by Benjamin West (above) and the

other by Arthur William Devis (below) a year later.

Both draw on imagery associated with the death of

Christ but one is ridiculous, the other deeply moving.

West portrays a public and national event, out on the

quarterdeck; Devis a hidden tragedy within the dark

confines (although painted too tall) of the Victory’s

orlop deck. West’s painting gets it wrong not only

actually (French musket fire would within minutes

have killed everyone in his crowded canvas) but

psychologically. The power of Nelson’s death, as

Devis recognized, was not its public glory but its

simple humanity.

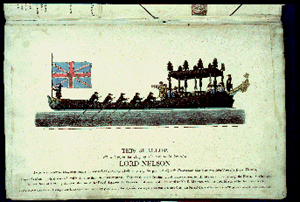

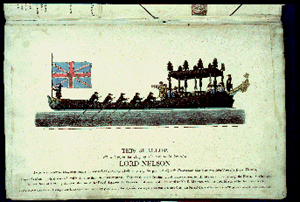

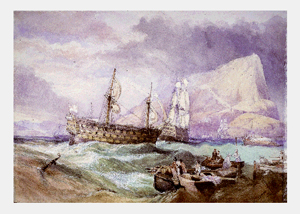

Two memorials to Nelson. In January 1806, he is absorbed (top) into

the world of the British Establishment, a royal barge taking his body

to a funeral in St Paul’s from which those he loved most were excluded.

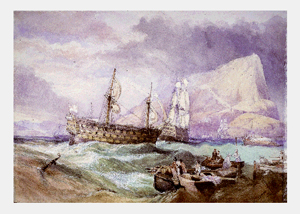

By the 1850s, when Clarkson Stanfield painted the Victory being towed

into Gibraltar after the storm (bottom), another meaning had taken over.

The jury-rigged Victory holds the secret within her decks, the body of the

admiral preserved in a barrel of spirits, lashed tight and stood over by a

Marine, essentially tragic and like all tragedies, essentially private.

Up to the eve of Trafalgar, and beyond, there were officers in the Royal Navy who had not grasped the essence of the new idea. The fleet engagement that had occurred most recently before Trafalgar was a text-book case of what the new thirst for uncompromising victory no longer thought adequate. Sir Robert Calder, the admiral commanding a British squadron off Cape Finisterre, the northwestern tip of Spain, had enjoyed by any account a glitteringly successful career, winning prizes, making his fortune, acting as Sir John Jervis’s flag captain at the Battle of Cape St Vincent, promoted to vice-admiral in 1804, both a knight and a baronet.

In the summer of 1805, Calder’s responsibility was one of the most essential nodes in the British defence network, cruising off the deep-water port of Ferrol, both to blockade the Spanish ships arming and victualling in there and to catch Villeneuve’s fleet as it returned from the Caribbean. The British force, reinforced by Barham in early July, consisted of fifteen ships-of-the-line, stretched out in a curtain to the west of Cape Finisterre. On 22 July, in a thick fog, they fell in with Villeneuve’s superior fleet, twenty to his fifteen. Calder found himself downwind of the French, but he managed to engage them and capture two Spaniards before night intervened. The poor man was honourable, personable and charming but not cast in the Nelsonian mode. He thought he had achieved a victory and sent a modestly heroic dispatch to London. The following day, he was anxious to secure his prizes, to attend to the battered condition of one or two of his own fleet and to avoid being caught by the huge fleet, consisting of Villeneuve’s 18 plus the 15 that would come out of Ferrol to join him, which now threatened him. Imagining that discretion was still the better part of valour, he did not seek to re-engage.

The newspapers in England were full of contempt for Calder’s lack of fighting spirit, for his ridiculous interest in preserving his little Spanish prizes and his failure to destroy the enemy. Lord Howe’s explanatory notes to the Fighting Instructions issued in 1799 had been unequivocal:

If the admiral himself behaved in such a pusillanimous way, public ignominy was the only possible outcome. The tradition of Hawke, Rodney, Howe and now Nelson had created an environment in which Calders could not survive.

When the news of the state of public opinion reached the fleet, Calder requested a court martial at which he might defend himself, feeling, as officers usually did in this predicament, that without a hearing his silence would be interpreted as accepting the calumnies against him. At the same time, an acutely political Admiralty required him to return home to England, realising equally powerfully that the London populace would never accept as good enough such an inconclusive form of fighting the French. The delays in communication between the fleet at sea and the Admiralty meant that Calder’s personal crisis persisted for the rest of the year. By the time the decision was made to send Calder home, it was mid-September. Nelson had by then returned to the fleet off Cadiz, where Calder was flying his flag in the 98-gun Prince of Wales. Such a ship would be an immensely important asset in any coming battle with the Combined Fleet. On instructions from the Admiralty, Nelson decided, at first, to remove the admiral from his flagship and send him home in the Dreadnought, still a ship-of-the-line, but the fleet’s worst and slowest sailer.

He wrote to Calder to say so and Calder, in a highly emotional state, replied:

Nelson relented, allowed Calder to remain in the Prince of Wales and on 30 September wrote to Barham:

Calder was popular among the other captains, capable of giving life-enhancing dinner parties for twenty of his captains at a time on board the Prince of Wales, the object of far more affection, for example, than stiff, solitary, wooden Collingwood, ‘another stay-on-board Admiral, who never communicates with anybody but upon service,’ as Captain Codrington of the Orion described him. It is possible, in this light, to see Nelson’s leniency as an act of war: its respect for an officer’s honour would have bound the captains of the fleet to him with a gesture only they would have understood. Such trust would win a battle in a way that the mere presence of the Prince of Wales might not.

Nevertheless, Nelson was worried about Calder, anxious about the outcome of the court martial, not sure that Calder quite understood the severity of his predicament, and was acting ‘too wise’, as Nelson wrote to Collingwood. The court martial was held on 25 December 1805, but even by then Calder had not understood. Defending himself against the charge that he did not renew the action the following day, he said:

Not to have done what he did, he said, would have been ‘rash and imprudent’. He congratulated himself on having exercised ‘a sound discretion’. He did not like the idea, as he wrote to Barham, of the ‘danger I must have exposed my squadron to, as also the country, if I had madly and rashly done what John Bull seems to have wished me to have done.’ Pompous, wordy and non-Nelsonian, everything Calder disparaged was precisely what, in the light of Trafalgar, he should have done: rashness, imprudence, exposure to danger, madness, what John Bull wished for – all this was central to Nelson’s grasp of the heroic.

At his trial, Trafalgar had come and gone and Calder had missed it:

He had no such luck; he made the appallingly thick-skinned error of claiming that, although he had been absent from Trafalgar, he was nevertheless due his share of the £300,000 prize money voted by parliament after the battle; and the judgement of the court must have driven a stake into the poor man’s tender, 18th-century heart.

The world had moved on past him and Calder was never asked to serve at sea again.

Nelson had an instinct for devastation and the people of England detected it in him. He knew in his bones that the public demand was for convincing and destructive violence, not a harmless strategic victory. It was what he had gone for at Cape St Vincent and delivered at the Nile and again in Copenhagen. He had tried and failed to deliver the same in the Canaries and in a catastrophic raid on Napoleon’s invasion fleet in Boulogne. In the media-rich environment of early 19th-century London, this was, if nothing else, a canny stance. He was, consciously or not, the hero-thief. In August 1805, for the fortnight he was back in London, he was mobbed in the streets like a star. His old friend, Lord Minto, chanced on him one morning:

Those last words are acute: the Nelson story was rising up into the realms of fiction and theatre. Later he was seen in the Strand:

His appearance was irrelevant. These were inner qualities, only apparent to the adoring crowd, seeing in his slightest gesture, as they see in all heroes, the workings of a wild and catastrophic heroism. He was summoned for interviews by ministers and officials. The country looked to him for its prodigies of conflict and its miracles of victory. On 24 August he wrote to Captain Keats, one of his Mediterranean band of brothers, from the house at Merton, to the west of London, which he shared with Emma Hamilton: ‘I am now set up for a Conjuror, and God knows they will very soon find out I am far from being one.’ The country expected magic; Nelson, who had been careful throughout his career to promote this mould-breaking, magic-delivering idea of himself, now found the wave he had set in motion taking on a life of its own.

The fantasy of sudden and violent victory at sea was something deeply shared in England. It reached what, at this distance, seems like the most unlikely of corners and was far more widely spread than merely among the jingoistic, navy-admiring French-haters. William Wordsworth, for example, who in the 1790s had been agonisingly alert to the savagery and psychic destruction of war, nevertheless nurtured a half-guilty, voyeuristic vision of himself as a fighting sailor.

It is, for Wordsworth, a moment of visionary apocalyptics, a shuddering, vicarious delight at the tales of battle and the need for courage, resolution and skill which they impose. The received ideals of courteous politeness no longer satisfy. Those, perhaps are what a wise man should delight in, but they are not enough. Deadly fighting and fighting to the death reaches deeper into the modern heart than politesse and the observance of rank and order. Wordsworth’s guilty confession acknowledges a new world bubbling up under the skin of the old. And to the general populace Nelson, more than any other man in the country, looked as if he had the secret of that new world in his hand. For Wordsworth, Nelson’s genius consisted, more than anything else, in ‘turbulence’.

Fascinatingly, in the terms they use to describe what they do, Nelson’s approach to battle mimics Wordsworth’s idea of what poetry needed to be. This is not to claim that battle is guided by aesthetic concerns, merely that Nelson’s form of battle, so clearly drawing on the Hawke-Rodney-Howe inheritance, but given heightened intensity in the psychically dynamic and inventive years around Trafalgar, takes as its essential merits precisely those qualities which Wordsworth requires for the new poetry: immediacy; a dignity given to the common man; dispensing with the fripperies; a sense that the moment of crisis is engaged with the ultimate metaphysical realities; interested more in the essence of what is to be done than the niceties of form; quite unaffected in manner, ‘scrambling into action’; inspiring in a way those around both Wordsworth and Nelson cannot quite explain; richly, deeply and humanly sympathetic; ruthless in its pursuit of the ideal; prepared to engage with the broken, the anarchic and the chaotic in pursuit of the goal either of victory, which is a form of revelation, or revelation, which is also a form of victory.

In both of them there is a deep distrust of the affected world of 18th-century society. From the beginning, Wordsworth proudly declared his crudeness, his lack of courtesy, his plain truth.

This is battle without decorum, without the pretty and elegant evolutions on which poetry had previously relied. Like Nelson, never loath to repeat his essential point, Wordsworth’s language, he says again and again, is ‘the real language of men in a state of vivid sensation’, ‘the very language of men’ addressing ‘the essential passions of the heart’ in ‘a plainer and more emphatic language.’ ‘What is a Poet?’ he asked, as Nelson might have asked what a fighting man might be. ‘He is a man speaking to men. He is the rock of defence of human nature; an upholder and preserver, carrying everywhere with him relationship and love.’ In this light, it becomes clear that Wordsworth’s basic conception of the human condition is battle.

This is no more than core Rousseauism, a rejection of ‘social vanity’, but given a new fighting ferocity. It is as if Wordsworth, in his programme for a new kind of poetry and a new kind of society, is drawing up a plan of attack, whose forms and emphases mimic Nelson’s in the months and years before Trafalgar. ‘All good poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings,’ Wordsworth famously wrote, just as Nelson insisted, again and again, that the purpose of battle was to annihilate the enemy by a release of essential fighting energies. A fusion of slow understanding, the application of the will and an unbending enmity towards the hypocritical, the weak, the affected and the wrong drives them both. ‘I have at all times endeavoured to look steadily at my subject,’ Wordsworth wrote. ‘The style is manly,’ and whatever beauty, he wrote modestly, may be found in his poetry, it resides ‘in the sense of difficulty overcome.’ Poetry is victory. In such a martial conception of art and life, beauty and victory become the same thing. Poetry is no longer bound up in books and metrical forms. Poetry, as Hazlitt would describe it, was to be found ‘wherever there is a sense of beauty, or power or harmony.’

Direct, fierce, daringly bereft of ornament or complexity, focusing on the central task, impatient with frippery, allowing the plain and open approach its vigour and clarity, Wordsworth, at precisely the same historical and cultural moment, had become to poetry what Nelson was to battle. Both were driven by a desire for the primitive and the passionate, that dreamed-of, unequivocally manly moment in the history of the world when daring coloured the acts of men:

Action would erase the effeminate hypocrisies to which both poet and admiral considered themselves opposed. ‘The ready way to make a mind grow awry is to lace it too tight,’ Coleridge had written in his notebook in November 1801. Here were his passionate contemporaries, both of them his heroes, looking for resolution in violence.

Nelson had been dwelling on how to bring the French and Spanish fleet to a conclusive and final victory at least since October 1803. The long and grinding months on blockade off Toulon, the chase across the Atlantic and back again, the couple of weeks and the hectic discussions in England in August 1805 had all provided him with the opportunity to develop a plan. He was clear from the start. There was to be no shilly-shallying. ‘The business of an English Commander-in-Chief,’ he wrote in a memorandum probably written off Toulon in 1803, was to lay ‘his ships close on board the Enemy, as expeditiously as possible; and secondly to continue them there, without separating, until the business is decided.’ There was to be none of this long-distance elegance. It was to be close, bloody, attritional, naked and decisive. At this stage, he was thinking only of a relatively small fleet action, involving perhaps eight or nine ships on each side. Nelson’s initial plan was quite conventional: to bring his full force to bear on a part of the enemy fleet, push through them to leeward, à la Howe, accept that some damage would be done to the British ships during the attack, but confident that straight dealing would overwhelm the enemy in detail.

Two years of dwelling on the question developed it. Nelson, predicting he would have more ships with him than turned out on the day, initially decided to attack in three divisions. One, made up of the fastest ships, would be held in reserve, to windward, to descend on any part of the battle where it looked as if they were needed. With the other two, as he told Sir Richard Keats, strolling on one of those August mornings in the garden at Merton,

This, as the great naval historian Sir Julian Corbett described it, was ‘a return to primitive methods: the three squadrons, the headlong charge and the mêlée. He seems to insist not so much upon defeating the enemy by concentration as by throwing him into confusion, upsetting his mental equilibrium in accordance with the primitive idea.’ A scribbled note, recently discovered among a file of letters from Nelson to his elder brother, seems to have, on its reverse side, a rough sketch by Nelson of exactly such a plan in action, clearly describing his method of attack when in London in August 1805.

After Nelson joined the fleet, he described the plan to his captains on 29 September in the great cabin of the Victory:

The ‘Nelson touch’ was a phrase Nelson had often used in letters to Emma. Between them, it carried slight erotic overtones: ‘Touch and take’ was another variant he often used, implying closeness, that electricity, an intimate violence. Its meaning is nowhere spelled out, but it certainly cannot mean overwhelming the rear of the enemy fleet, nor of driving through them to the leeward side, as both of those tactics had been well known in the navy for 20 years. What it is much more likely to mean is the style of the attack: giving Collingwood complete command of the lee division; trusting his captains to their own initiative once the battle had begun; creating an atmosphere among them in which it felt impossible not to win; and as Collingwood wrote to Admiral Sir Thomas Pasley after the battle, ‘to substitute for exact order an impetuous attack in two distinct bodies.’ Those are the electrifying atmospherics which lie behind the victory at Trafalgar, the introduction of chaos as a tool of battle.

The written memorandum Nelson issued to his captains on 9 October is highly detailed: three divisions, two to attack, one as reinforcement; Collingwood’s line to attack 12 from the rear of the enemy fleet; Nelson attacking in the centre; the enemy van to be left to its own devices. The plan, as described in the memorandum, does not describe a hell-for-leather chase all morning across the ocean to get to the enemy. The British fleet are to arrange themselves in their divisions just out of gunshot of the French, in close order, sailing parallel to them. Only then would the signal be given to attack, Collingwood’s division first, in line abreast, followed by Nelson’s, also in line abreast, the third division hanging off, waiting to see where its force could be brought with greatest effect.

This is so unlike what happened at Trafalgar that it left most of the captains confused. There was no reserve squadron and the ships designated for the reserve squadron were mostly attached in a slightly muddled way to Collingwood’s line. The two columns did not gather themselves into coherent aggressive bodies just out of gunshot but each ship of each column plunged into battle one by one. The distance between the head and tail of each of the British columns was about 7 miles. As they approached, Collingwood gave the signal for each ship to make for the enemy ship nearest to him in the rear of the Combined Fleet, each pushing through, according to one of Howe’s signals. Nelson apparently feinted towards the enemy van, keeping Villeneuve in a state of uncertainty, and then pulled back towards the centre and drove into the enemy in line ahead, pretty much on the Rodney model.

To a critical mind the whole approach was not only chaotic but intensely dangerous. There is one document in particular, anonymous but almost certainly written by an officer on board the Conqueror, Lieutenant Humphrey Senhouse, and almost certainly written soon after the event, which, a little tentatively, dared to criticise the haste and confusion with which Nelson jumped his fleet into the attack. ‘Of the advantages and disadvantages of the mode of attack adopted by the British fleet,’ Senhouse ventures, ‘it may be considered presumptuous to speak, as the event was so completely successful.’ The pall of perfection was already beginning to fall on Nelson’s great battle. Senhouse then described what should have happened:

Senhouse was no bewigged stick-in-the-mud; he had volunteered for the terrifying role of sailing fireships into the Combined Fleet still at anchor in Cadiz. Nevertheless, this is the non-Nelsonian voice of order, consideration and regulation. It is the 18th century addressing the spontaneity and near-anarchy of Nelson’s method. By the original plan, all except the lumpen sailers, the Britannia, Dreadnought and Prince, would have come into action at the same moment and the rear and centre of the Combined Fleet would have been crushed and eventually annihilated by the impact.

But that wasn’t how Nelson did it on the day. Without forming into mutually supportive bodies of ships, the British fleet, raggedly arranged in its two columns, were even now being thrown into action like confetti at a wall, the difference being that this confetti was explosive and the wall far from strong. The reason for the British success at Trafalgar was not tactical. The tactics were immensely weak. The success depended on the independent ferocity and fighting aggression of each British ship and on the example of leadership given by Nelson to his captains. As Lieutenant Senhouse put it:

In others words, love, honour, zeal and skill won the day. Without those qualities, this officer maintained, or even with them when faced with a resolved and skilful enemy, it is perfectly possible that Trafalgar would have been a catastrophe.

Senhouse, after the event, allowed himself the luxury of imagining disaster. The two columns of the British fleet, in their slowness, are drifting down in the light airs towards the enemy. The day is calm and clear. The swell pushes through. All is alert. The bands are still playing. The British ships seem to hang, almost immobile, in front of the enemy cannon arrayed so thickly before them.

He is expert enough to know what a British fleet would have done if they were defending against such an attack.

Assuming a firing rate of a broadside about every 90 seconds, and each broadside firing an average of 37 guns, the leading ship would in the space of about quarter of an hour be sailing through a block of air filled with about 1,000 roundshot, each one aimed at its hull and rigging. If the wind fell, or a sudden calm came on, the leading ships would, in Senhouse’s words ‘be sacrificed before the rear could possibly come to their assistance.’

These are not the armchair thoughts of an amateur strategist reflecting much later on Trafalgar after all is over. This, among officers of the British fleet, is the quality of apprehension on the morning of Trafalgar itself. What is Nelson doing? Why does he not allow us to come up? What mad daring is this? How can he hope to survive? And among the French and Spanish, those questions must have been equally insistent. Nelson, for friend and enemy alike, was imposing exactly what he had told Keats a couple of months before: ‘I think it will surprise and confound the Enemy. They won’t know what I am about. It will bring forward a pell-mell Battle, and that is what I want.’

Confusion and its attendant chaos was, for all his planning, Nelson’s chosen method of battle. He knew he would win like that, even if at some terrible cost to the British fleet. As the great 19th-century French naval historian Julien de la Gravière wrote, ‘Le génie de Nelson c’est d’avoir compris notre faiblesse.’ The genius of Nelson was to have understood our weakness. Or, as Miles Padfield has written more recently, the chaotic, piecemeal mode of attack adopted by Nelson at Trafalgar was ‘the tactics of disdain’.

Everything was visible as they approached: the broadsides of the enemy, with their iron teeth turned towards them, now and then trying the range of a shot to gauge the distance, so that they might, ‘the moment we came within point blank (about six hundred yards) open their fire upon our van ships.’ The Santísima Trinidad, with four distinct lines of red painted the length of her hull between the gunports, was clearly seen about eleven ships back from the van of the Combined line. Nelson was driving his column towards her. On the Neptune, just behind him, one of Fremantle’s midshipmen, 16-year-old William Badcock, was gazing at the Spanish flagship,

Everything on every ship was now in order. The galley fires had been extinguished, flashproof screens made of thick woollen cloth known as ‘fearnought’ had been fitted around the hatchways through which powder from the magazines, where it was stowed in copper-hooped barrels which would make no sparks, would be passed; the shot racks in which the 18lb, 24lb and 32lb balls were stored had been drawn out from under their usual coverings; the guns, usually triced up tight to prevent movement at sea, had been cast loose. Crowbars – handspikes – used to lift and point the guns were lying at hand beside them on the decks. Goats and pigs had been sent down to the cable tier, the deepest and most protected level on the ships; the captain’s ducks and geese were more often left in the coops to take their chance; Collingwood didn’t move his pigs from their sty and they were killed during the battle. In the near lightless depths of the cockpit on the orlop deck, sails were spread out on chests, the surgeon’s saws, knives, probes, bandages and tourniquets all put in order. The surgeon’s task, as the Admiralty described it, was ‘to be prepared for the reception of wounded men, and himself and his mates and assistants are to be ready and have everything at hand for stopping their blood and dressing their wounds.’ The carpenter and his crew were ready down below with shot boards and plugs of wood with which to repair underwater damage from enemy fire.

Silence prevailed as the men and boys stood to their guns. Men tightened their handkerchiefs around their heads. On the leading ships, shot fell short alongside and then went over. Then, in Victory, a shot went clean through the main topgallant sail. Then seven or eight ships opened fire on her, ‘a heavy and unremitting cannonade’ and within a minute or two, as Dr Scott, Nelson’s secretary, was speaking to Captain Hardy on the quarterdeck, a roundshot killed him. That is casually said, but what exactly happened when a cannonball hit a body?

It could cut a man in two; it could remove his head or any one of his limbs, not neatly but leaving a ragged tear where the limb had been. The man died either through sheer destruction of life-critical tissue – the hammocks in their netting were spattered with it – or through the rapid loss of very large quantities of blood. For a few moments, the heart might respond to the trauma by increasing the pulse-rate, but that response would only have the effect of killing the victim faster. Scott’s blood would have pumped out all over the quarter-deck, his flesh would have begun to turn pale, his mashed remains would have been thrown over the side, and the only memory of this sophisticated, multi-lingual, doggedly loyal man, who wrote letters to Emma on Nelson’s behalf, would have been a pool of blood on Victory’s pale deck timbers of Prussian deal.

‘Is that poor Scott who has gone?’ Nelson asked, suddenly looking round, a question that reveals how death could appear so casually here; a man Nelson knew as well as any other, walking on his quarterdeck, speaking to his captain, and then, in the next instant gone, not lying there as an elegant corpse, but his identity erased, his body not butchered or hurt but mangled and distorted, a muddle of blood and bone and half-human features where a man had been.

When Victory was 500 yards from the enemy line, her mizzen topmast was shot away. Another shot struck and destroyed the wheel. Within another two minutes, a double-headed shot – a heavy, stubby bar of metal which spun through the air – sliced through a line of eight marines, killing every one of them. Yet another smashed into a launch, hit the deck of the Victory and a splinter flew towards where Hardy and Nelson were walking on the quarterdeck. It tore off the buckle from Hardy’s left shoe.

For young Lieutenant Nicolas on the Belleisle, newly challenged to the display of phlegm, war became suddenly horrifying:

On the decks of the Belleisle a dozen men lay dead. Ten more were wounded and in the hands of the surgeon far below. Between the decks, at least protected by the thickness of the oak, there was nevertheless tangible fear: no noise, no laughter, no show of hilarity; perhaps some jokes but nothing more. Men stood there listening, or peering out through the gunports to judge the distance. ‘I felt a difficulty in swallowing,’ one sailor, Charles Pemberton, remembered of just such an attack a few years later.

When at sea, the drummer beat the men to quarters every night. The entire ship knew what its fighting quarters were, eight men and a boy to the lightest guns, fifteen of them to the heavy 32-pounders, and they habitually sang to the drummed rhythm.

Not now though. All is perfect death-like silence. The guns have been shotted and the slow-matches lit and placed in their tubs, a stand-by system in case the flintlocks misfired. The lieutenants have been through the decks, reminding the marines and those seamen who are designated as boarders, what to do if they were ordered to board the enemy. Pikes, cutlasses, and pistols have been issued and stowed. Buckets of good sweet drinking water and tubs of cinders or sand, for when the deck becomes wet or slippery, have been placed between each pair of guns. Behind them the grape and canister, the roundshot, the waddings, the powder cartridges and the powder horn are all laid out according to designated patterns. Pistols are kept ready in case a gun should fail to discharge when the flintlock is released. If a gun ‘hangs fire’ like that, a ‘pistol with half a cartridge of powder fired slantway down the touch hole of the gun will always discharge the gun.’ As it does so, a burst of blame drives up from that touch hole and scorches the deck beams above. The captains have toured all parts and urged the men ‘to courage and duty’.

On the Neptune, Thomas Fremantle speaks to his men at their different quarters. They were to think of their country, and all that was dear to them. The fate of England, as Able Seaman James Martin remembered Fremantle’s words

That’s why Nelson loved Fremantle: because Fremantle loved England and everything in it and understood what might be called the ‘Achilles Deal’ which Nelsonian battle required. What Martin may not have realised is that Fremantle was remembering the inspirational words he had read in Pope’s translation of the Iliad, Book V, in which Diomed addresses the Greek warriors:

Men were stationed in the tops – narrow platforms on each mast which gave an overview of neighbouring ships – their duty both to trim the sails and, in some ships, to fire down with muskets on the enemy poop and quarterdeck if it came to close action. Others on the forecastle and poop had as their task the handling of the sails during the battle: to back the topsails if the ship needed to lose way, to haul on the braces of the great yards if the ship was to tack or wear. Every man was at his quarters. The moment of intimacy was upon them.