The setup was perfect. Too perfect. On April 4, I was going to turn eighteen. On that same date, I was scheduled to be in Cancún, Mexico, on my high school senior trip. That deserved its own rock song; I’d be sitting on the beach at noon, waking up to face the tropical sun, with a gorgeous brunette on a towel by my side. She’d hand me a Corona with a wedge of lime and say, “Happy birthday, Ned. You’re eighteen.” And then she’d smile.

Didn’t exactly work out that way.

I heard about the Cancún trip in the fall of senior year. I didn’t have any idea what it was. I was ignorant of the whole senior trip ritual, where wealthy teenagers with lenient parents escape to warm climates to get drunk and have casual sexual encounters. I’d just hear it whispered, “Cancún.” “Man, this homework sucks. I can’t wait to go to Cancún.” “I hate school. The only reason I’m still here is for Cancún.”

One day, Owen, my bug-eyed Russian friend, approached me in the hall and asked outright, “Dude, are you going to Cancún?”

“Probably,” I said. That was good. “Probably” made me sound cool—like I’d known about the trip all along—but it was noncommittal. I didn’t want to commit to this before I knew what it was.

“All right,” Owen said, throwing his arm around me.

I broke his mood by asking the nerdiest possible question. “Uh, what is Cancún? Exactly?”

“Stupid, it’s the senior trip. We fly down to Mexico to party for a week.”

“Oh. How many people?”

“Whoever can afford it, like forty, fifty people. Lots of girls is the important thing.”

“How much does it cost?”

“Eight hundred bucks.”

“Damn.”

“Dude, are you going or not? And don’t tell me you can’t afford it. You’re probably the only guy in the school who can afford it, since you’ve got your own money. What do you have by now? A hundred thousand dollars?” Owen was exaggerating. I had about ten thousand dollars saved up at this time; no way was I spending 8 percent on some trip.

“I’m just saying, eight hundred bucks is a lot of money.”

“Ned, you want to do this. I know you do. I’m telling you now so you can room with me and Josh and Alex.”

“Dude, we need somebody else to room with us.”

I knew this could be trouble.

“I’ll go.”

“Okay!” Owen grinned. “So go talk to Emily! She’s, like, the coordinator. She has sheets for you to fill out.”

“Cool.”

Talking to Emily wasn’t going to be fun. She was one of those criminally gorgeous high school girls; she made me feel about eight years old. If she found out I was going on her trip, she’d laugh in my face. I sought her out a couple of days later.

“Hey, Emily?” She was sitting with the other preppy seniors in their segregated area by the Snapple machine. “I’m, uh, going to Cancún, and I need some literature?”

“Oh, Ned, you’re going?” Her smile was too wide. And she had said my name, which was suspect—I didn’t even think she knew my name. “Here, let me give you the sheet.”

She handed me a colorful piece of paper. “This,” she bubbled, “has all the info! About the trip! See! The name of the company is Student Travel Services; the trip costs eight hundred fifty dollars; we leave on April second …”

I wasn’t looking where Emily was pointing, though. I was checking out the flyer’s photo: a row of thonged butts under the caption, “Fun in the Sun.”

“Okay?” Emily summed up whatever she’d been telling me.

“Yeah.” I folded the flyer neatly, tucked it in my pocket, and took it home to show my mother. “Mom,” I said, closing the door and throwing my backpack on the dining room table. She was sitting with her feet up, doing a crossword puzzle.

“Hi, honey,” she said, looking at me. “How was your day?”

“Good, good … ah, Mom, I have to show you this.” I pushed the “Fun in the Sun” flyer in front of her. “I’m going to Cancún in April.”

“Whaaat?” Mom jumped from her chair, clutching her crossword like a shield. The flyer dropped to the ground. “Whaaaaat?!”

“It’s spring break! I’ve done very well in school. I deserve a reward, right? It’s just, you know, a vacation. To Cancún.”

“Vacation? Ha! It’s an orgy of sex and drugs!” She grabbed the flyer off the floor and inspected it.

“It’s not an orgy of sex and drugs.” I was wistful. “It won’t be for me, anyway.”

But now Mom had seen the thongs. “Look at this!” she howled. “No, no, no, no, no, no, no!” Uh-oh, the Seven Nos. Those were always a bad sign. “You are absolutely—”

For the next few minutes, we had an interesting scene. Mom yelled at me about Cancún and I yelled back, but the problem was, she was right. The place was a seedy hole, and when I tried to describe it as anything else (“There are ruins, Mom, I’ll see the Cancún ruins!”), she would burst out laughing. Then I would chuckle, despite myself, until our shouting degenerated into laughter. At some point, I noticed that our apartment door was open; it always opened while we fought, delivering the action in stereo to our neighbors.

I closed the door and gave in. “Okay, fine, Mom,” I smiled. “You won’t let me have a wholesome time in Cancún. I guess I’ll have to suffer.”

She sat back down. “Don’t try to pull one over on me, Ned,” she said. “I was young once, too.”

I walked to my room, plopped down on my bed, and started strategizing. How could I get to Cancún without Mom finding out?

It wasn’t such a stretch. I’d snuck out on my parents before and lied about my whereabouts to stay at parties. The method was always the same:

Me: “Mom, I’m sleeping over at James’s house tonight.”

Mom: “You are? Oh, how is James? Is he doing okay?”

Me: “He’s fine, Mom. I’m sure he says hi.”

Mom: “Well, if you’re going there, leave the phone number by the stove so I don’t have to look it up if I want to call.”

Then I’d leave the phone number—James’s legitimate phone number—and head out, knowing she’d never call. We had a tacit pact—if I showed enough respect to give her a phone number, she’d show enough respect not to check on me.

Cancún would operate on the same principle, but for a week, instead of a night. I’d tell Mom and Dad that I was staying at James’s country house this time. The plan was airtight; I actually had stayed there a year before so the element of parental trust was in place. I’d give my parents a phone number, and they wouldn’t call. I’d be home free—eighteen, on the blanket with my beach babe, as planned.

I went to school the next day with an eight-hundred-fifty-dollar Cancún deposit. I handed it to Emily by the Snapple machine.

“You know, it’s so great that you’re going, Ned,” she said earnestly.

Emily’s act was beginning to bother me. If she liked me—which would be unthinkably cool—I needed to move fast. I’d found that girls, when they developed crushes, were never receptive for more than two weeks. Sure, they’d remember a crush for two years and then tell you, “Ned, back in sophomore year, I thought you were sooo cute.” But they were only open for two weeks—you needed to act quick.

“You’re really glad I’m going?” I asked Emily. “I mean, glad glad?”

“Oh, yeah,” she said. “You round out a whole room. It’s you, Owen, Alex, and Josh. And I get paid by the room.”

“You do?”

“Uh-huh. It’s a sponsorship. The company sending everyone to Cancún pays me based on how many people go. I am making so much money. You wouldn’t believe it.”

“Oh.” Glad I got that cleared up.

• • •

I went through the dark months—November, December, January—without any changes on the Cancún front. My escape plan stayed the same: (1) leisurely tell my parents I was going to spend the week at James’s country house; (2) get on the plane; (3) party; (4) pray for no phone calls. But at the end of January, two things happened: I took on the role of Jesus, and I got a girlfriend.

Jesus first, though I assure you, I was more surprised to get the girlfriend. My church, St. John’s, which Mom had made me attend all through adolescence, held an annual Easter Passion, a reenactment of Christ’s crucifixion, with congregation members playing the major characters. St. John’s liked to cast teenagers* in the Jesus role—I don’t know why; we were singularly unqualified to play the pure-minded son of God, but whatever. For two years, my friend John had played Jesus, but that year, he declined. Because there was no one else to play the part and (much more significantly) because Mom pressured me, I took it.

As for the girlfriend, wow. Her name was Judith, and she was everything I’d missed in high school—love, status, constant physical attention—wrapped up and delivered in a slick, beautiful package. I met her at a party at Alex’s around Thanksgiving. She was there with a guy. She had on a dark top with a silver skirt, showing off her midriff. I had shlubby pants, a collared shirt with a T-shirt under it, and my calculator in my pocket.** I’d drunk three beers, which was enough to get me to talk to people.

I needed to call Mom (to tell her I’d arrived safely at “James’s”), but I couldn’t make the call on Alex’s phone because the party was too noisy. So I began cruising for a cell phone. I figured I’d find some cool guy, borrow his phone, and huddle in a closet to talk with Mom. Instead, I ran into Judith; she was just finishing up a call out on Alex’s porch.

“Excuse me, ah, hello, my name’s Ned, and I was wondering if I could use that, your cell phone, for a second.”

“Hi!” she said. She had such a happy little hi. It had a lot to do with my falling in love with her later on.

“Um, hello.”

“Are you a friend of Alex’s?” she asked.

“Since grade school.”

“Oh! Well here, sure. The buttons work like this …” She drew herself close and showed me.

She was a gorgeous girl, and we talked for a while. Afterward, as I walked off the porch, Alex himself asked me if she was my girlfriend. I smiled. “I wish.”

In the next two months, Judith dumped her boyfriend, got my phone number, and seeped into my life by showing up at events that I showed up at. It was confusing because she was so cool. Capital C Cool. It wasn’t her money or her cell phone; it was the way she carried herself. She was a member in good standing of the Cool People. She went to another specialized public high school, but if she had gone to Stuy, I knew she’d be hanging out with Emily by the Snapple machine.

Our first date was a self-guided tour of a college both of us were looking at for next year. I don’t know how I did it but, at some point, I got Judith into a secluded room, asked her out, and kissed her, all in rapid succession—all of which she was receptive to. Really.* I was James Bond for a day. Once the relationship began, though, I reverted to my bumbling self.

Physically, Judith was all smile. Her smile could thaw snowdrifts: perfectly spaced teeth, wide without being too wide, innocent, and enthusiastic, like she really wanted to see me, which was something I’d never experienced. She had brown eyes and brown hair; she duped me into thinking she was five feet five, with her sharp posture and high-heeled shoes, but she was actually five two. I got used to it. She had small glasses, small hands, small breasts—only her temper, as I came to learn, was ponderously massive.

Judith and I started going out January 26. Only a week into the relationship, we were talking every day—I called her from a pay phone at Stuy. She’d get mad if the calls were less than ten minutes, so I’d bring extra quarters. During one of these conversations, I told her about Cancún.

“Ned, we have to make plans for your birthday.”

“I’m not going to be around for my birthday. Didn’t you know? I’m in Cancún from April second to April eighth, on the senior trip.”

“Oh.” That was something I’d learned to fear from Judith: the Clipped Oh. It meant trouble.

“Didn’t I tell you about Cancún?”

“No.”

Silence.

“I’m not going to cheat on you or anything,” I lied. If the beach babe came along, I’d cheat on Judith in a flash.

“Oh, sure, you’re not going to cheat on me, but you’re going to get drunk a lot, aren’t you?” Judith was always suspicious and judgmental about that stuff.

“No,” I lied again.

“Oh.”

More silence.

“I have to go,” I said.

“Yeah, bye.” Click. Judith was a fan of the hang-up-and-wait-for-Ned-to-call-back tactic. I ignored this volley, though, and went to class.

My life had become a two-front conflagration: on one side, Judith—fighting with her, comforting her, and gradually falling in love with her; on the other side, playing Jesus.

The Easter Passion was run by Dale, a head honcho in the choir. Dale had some serious ambitions for our church. He wanted lavish costumes and tortured acting. He wanted to reveal the soul of Jesus. And he had written his own eleven-minute song, “I Saw Jesus,” to anchor the show. (It was actually quite good.)

On the first day of rehearsal, I showed up alone so Dale could guide me step by step through the emotions of Jesus. “Ned, you have to understand that Jesus was a normal man. That’s what’s been lost in the centuries since he died. He wasn’t a god, although he had God in him. He was just a man, with a man’s fears and desires and hopes and faults. And you need to capture the difficulty of his decision—his decision to die.”

“Okay.”

“So you need to try this line again: ‘Jerusalem, Jerusalem.’ I don’t want it to sound like Hamlet; I want it to sound like a normal man.” I worked on that for a while; finally, after I told Dale that I was exhausted, he sent me home with some flyers.

“You can give these to people at your school.” The flyers were yellow, with a stylish picture of the Son of Man. They read, “Come to the Saint John’s Passion Play, April 2, at 7:30 P.M.”

I’d walked halfway home before it hit me: April second, at seven thirty! April second! That was when I was scheduled to leave for Cancún! I ran home and called Owen.

“Hey, dude, it’s me. I have some questions for you about Cancún.”

“What?”

“When does the plane leave?”

“April second, at eight thirty. Why?”

“Oh, man. I have to be Jesus on April second, at seven thirty!”

“What?”

“I need to play Jesus. In a church play. I’m sort of signed up for it.”

“Dude, I don’t know how, but you have to get out of that. If you don’t make it on this trip, we are all screwed. Me, Josh, and Alex will have to pay more money, and we will all personally kill you.”

“Okay, okay,” I mumbled. “I’ll get out of it.”

I hung up the phone and went to Mom. “Sorry, I can’t be Jesus,” I said.

“Whaaat?” You’d think my mother would get tired of this act, but no. She jumped off the couch and yelled, “You are not getting out of playing Jesus! You are committed to it, and you committed yourself to it, and it’s a very important commitment! You cannot turn your back on your church that way!”

“But I have to be at James’s country house on the day of the play!”

“No, you don’t! That can wait. If you knew about that, you should never have agreed to play Jesus!”

I checked the apartment door; miraculously, it was closed.

“Mom, I didn’t even want to play Jesus, y’know? You kind of made me do it, and now I’m telling you that I have to do something, and I can’t be Jesus on the day I’m supposed to, and, uh, they’ll have to find someone else.” I was wavering, and Mom could tell.

“Absolutely not. You are still living under my roof, in my house, and you committed to something. If you cancel, you will be letting down a lot of very nice people.”

“Well, if I don’t leave April second, I’ll be letting down a lot of nice people, too.”

“Ned,” Mom said, grabbing my cheeks like she used to do when I was six. “You are going to be in this play. That’s it.”

“Okay,” I said.

I walked slowly to my room. The last thing I needed now was to deal with Judith but, for some reason, I called her.

“Hey.”

“Hi!” That was it. Her happy hi; I loved to hear it. “How are you?”

“Not so good. It looks like I can’t go to Cancún.”

“Oh. Why?”

“I have to be Jesus the same day.”

Judith started laughing. She laughed for seconds, probably minutes. A minute of laughter is long on the phone.

“What’s so funny?”

“Ned, you are so silly. You have—hold on.” Laughter. “You have all these fantasies that you try to live out.” More laughter. “You act like James Bond; you act like this rock star; and really, you’re just playing Jesus in your church.”

“Well, thanks,” I smiled. “I’m glad you’re so supportive of my hopes and dreams.”

“Listen, bubbelle.” (That’s what Judith called me when she was feeling happy.) “It’s okay. It’s—my God, it’s bad enough that I’m not going out with a Jewish boy; now I have to tell my parents I’m with someone who’s playing Jesus. Maybe it’s good that you don’t have to worry about that and Cancún at the same time.”

“Yeah, maybe.”

“What did your parents think about all this?” she continued.

“About Cancún?”

“Oh, I never told them.”

Silence.

“What?”

“What?” I asked.

“You never told your parents you were going to Cancún?!”

“No. I, uh, had a plan. I was going to tell them I was at this guy James’s house, see, and then I hoped they wouldn’t call—”

“Are you out of your mind?! Who am I dating? Are you crazy? Really, Ned, are you a sane person? Can you think what would have happened if you had gotten hurt? If you needed help? Can you even imagine?”

“Uh, I guess so.”

“This is ridiculous. You’re ridiculous. Thank God you’re not going to Cancún; you probably would have died.”

“I don’t think so.”

“Jesus—wait, I’m talking to Jesus, aren’t I?”

“Ha, ha.”

“Ned, don’t go doing crazy things. I care about you very much, and I don’t want you going to Cancún and getting hurt. Okay?”

That’s how it worked with Judith. First, the sucker punch—the “I-can’t-believe-you’re-such-a-jerk” chastising. Then the sweetness. It was a double whammy I could never fight. I’d convinced myself I wasn’t going to Cancún because of playing Jesus, but I suppose I was doing it for her too.

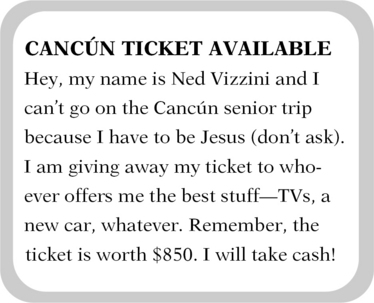

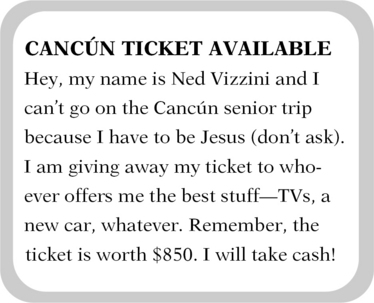

I got off the phone, sat at the computer, and typed:

The next day, I posted copies of the announcement all over school, nearly crying as I stapled them to bulletin boards. There’d be no beach babe for me—no “Fun in the Sun.”

I got three offers. A guy promised eight hundred dollars worth of marijuana; a girl offered enough Delta frequent-flier miles to go anywhere in the world for the next five years, and another guy presented a check for eight hundred fifty bucks. I took the check.

• • •

So I didn’t lose anything. I got my money back, and I played Jesus as a normal man (with Mom watching, of course—she said I was inspiring, and she was proud to have me as her son). Then I spent my birthday with Judith—she didn’t hand me a Corona with a wedge of lime, but she did say, “Hey, Ned, you’re eighteen!” And she smiled very nicely.

Still, there’s no rock song in that. I don’t even think there’s a lesson.

*The church never called us teenagers, though, always “youth.” We had “youth groups,” “youth services,” “youth Bible study,” “youth ministry.” St. John’s loved that word.

**I always took my calculator everywhere, because whenever I left it at home, it got lost in my house, and then I couldn’t find it when I needed it for school.

*This was all highly thrilling and unusual. At Stuy, I spent hours trying to dissect whether Girl A or B liked me; with Judith, it was clear from the beginning. All I learned during those high school musings was that if a girl likes you, she’ll look at you a lot. That sounds obvious, but it works; you just have to know who’s looking and who’s daydreaming.