Shortly after the turn of the century, my father, Moe Howard, who was a very young child at the time, listened with fascination to his father, Solomon, as he told him bedtime stories about his youth in Russia and his emigration to America. Decades later, in the late ’60s and early ’70s, Moe, whose retentive memory was spectacular, decided to write his autobiography and jotted down, in the minutest detail, his memories of those ancient bedtime stories. In the first segment of his original manuscript, there were hundreds of pages covering just my grandfather meeting my grandmother and hundreds more detailing their arduous journey from Russia to America.

Kovno (Kaunas), Lithuania, where Curly’s father, Sol Horwitz, was born.

World Book Encyclopedia

After my father died, the task of editing those voluminous notes down to size and completing his autobiography fell on my shoulders, and hundreds of pages of the Horwitz family’s ancestry were deleted.

Ten years later, while researching the mystery of Curly and his roots, I came across this mass of discarded material tucked away in a carton in my attic. Knowing that no book on my uncle Curly, the superstooge, would be complete without more details about his family, I found myself rereading page after page.

This is no ordinary story but a yarn that has the makings of a “Jewish Roots” and that describes where all the Stooges’ insanity originated.

Curly’s father, Solomon Gorovitz, was born in the city of Kovno (Kaunas), Lithuania, on November 4, 1872. At age fifteen, as was the tradition for orthodox Jewish youths, Solomon, shy and inexperienced, was sent to a rabbinical seminary over one hundred miles away in Vilna (Vilnius), where he would live at his cousin’s house during the two years of his biblical studies.

Taking along a few simple belongings, young Solomon made the difficult journey by foot, wagon, and train. To this wide-eyed, naive Lithuanian teenager, the trip and the radical changes in his life loomed as a frightening event.

Upon his arrival, Solomon breathed an exhausted sigh of relief when he was greeted by his cousin Nathan and then taken by horse and buggy to the Gorovitz home. It was here he met his second cousin, Jennie. Born on April 4, 1869, Jennie Gorovitz was three years older than Solomon. She was robust, with sparkling eyes and raven-black hair, a young girl who could be sweet as an angel one minute and a domineering martinet the next.

To Jennie, Solomon was far from being the boy every teenage girl dreams about. As the weeks passed, Solomon was bewildered by her scorn until another cousin, Victor, explained, “Don’t you know that you hurt most the people you love.”

Cousin Victor’s words helped to soothe Solomon’s wounded pride for the moment, but throughout his life my grandfather learned to totally ignore most of Jennie’s barbs, except those times when they became too thorny. Then he’d put on his hat, show her his back, and stride silently out the door. In later years, Curly, Moe, and Shemp referred to this as “the hat trick.”

Later, as Solomon’s graduation from rabbinical school drew near, fate stepped in to change his life forever. My great-grandfather had gotten word that the czar’s soldiers were roaming the country and conscripting all men of Solomon’s age into the Russian army.

To a religious Jewish family, the thought was intolerable, since Jewish boys were conscripted for incredible lengths of service and sometimes subjected to forced conversions.

This was a time of urgency, and the Gorovitzes had to take immediate action. They decided to give Solomon the identification papers of a young Jewish man who had died after serving his stint in the army. Aware that this ruse was certain to be discovered eventually, the Gorovitzes made plans to get Solomon out of the country and ship him to America.

Eastern Europe in the nineteenth century.

Map by Norman Maurer

This was easier said than done. The Gorovitzes realized that naive, unworldly Sol would never survive the difficult journey alone. On the other hand, Jennie was a strong, strapping young woman, and the two together would have more than a fighting chance to make it out of the country, but they had to patch up their differences, marry immediately, and leave for America together.

Opposites attract, and Mrs. Gorovitz, always the optimist, was certain Sol and Jennie would eventually learn to love each other.

But Jennie had a mind of her own, and it took some convincing to get her to agree to the marriage. The wedding was a hurried one, and immediately after the ceremony, my great-grandmother and -grandfather made preparations to send the newlyweds on their way.

Jennie’s bag was packed, and the senior Gorovitzes supplied the young couple with enough kopecks and rubles to cover the costs of lodging as well as bribes for the border guards and payment for passage to America. Mr. Gorovitz, however, was adamant about securing Jennie’s dowry, since the couple would need the money from it when they got to America. He placed one hundred rubles in a small sack and concealed it by sewing it inside the fly of Solomon’s pants. Little did he or Solomon realize the embarrassment that would result from this simple security measure.

And so our young couple joined several other young couples for their difficult trek across Lithuania, Poland, and Germany, finally arriving at their destination, the North Sea port of Hamburg.

They were packed like sardines in the ship’s steerage, and the voyage across the Atlantic lasted fourteen days. The seas were rough and, as was always the case in steerage, the trip was most unpleasant. This was especially so for Solomon, who constantly held his hands to his fly to protect his wife’s dowry; he had to endure with embarrassment the curious stares of his fellow passengers.

During the voyage, Jennie made detailed plans of how she would find work in America. Even at this early point in their married life, Jennie demonstrated that she was destined to take over as the family breadwinner.

The trip across Europe under Jennie’s guidance had taught Solomon respect for her capabilities and her honesty, qualities that he greatly admired. Neither a thinker nor a man of action, he surrendered his masculine authority then as he would continue to do throughout his life.

Upon the young Gorovitzes’ arrival at Castle Garden, New York, in 1890, they went through the usual immigration red tape and the typical problems caused by the ever-present language barriers. When asked their names by the immigration officer, Jennie, with her thick Lithuanian accent, replied, “Gorovitz.” To the officer it sounded like “Horwitz,” and Horwitz it would remain for the rest of their lives. Not so with Moe, Shemp, Curly, and Jack, who, for the sake of euphony, would eventually change their name to Howard.

Jennie’s oldest brother, Julius, who had previously emigrated to America, gave the newly-weds the first roof over their heads—a room in his furnished apartment at Twenty-Second Street and Third Avenue.

Curly’s fraternal grandparents in Europe, circa 1880. Chaim Nocham (Charles Norman) was born and died in a shtetl near Vilna, killed while rescuing the Torah from the town synagogue in 1900. Wife Dora died of starvation in a post-World War I famine in Russia.

Courtesy of Stanley Marx

There they were, Jennie and Sol, two strangers in a strange land, unaware that they would one day change the course of comedic history.

Jennie and Solomon started their family in 1891 with the birth of a son, Irving, a sickly child but nevertheless a joy because of the added realization that, according to law, Irving was an instant American citizen. Jennie and Sol catered to their new son’s every whim, since he was their firstborn and tradition gave him a special place in this blossoming Jewish family.

Irving, however, would one day be Jennie’s first disappointment, for he would grow up to become an insurance salesman and not the professional that Jennie, the typical Jewish mother, had dreamed about.

In 1892 Sol found a job as a clothing cutter. He worked hard until the union struck for a shorter work week and he found himself unemployed. Desperate to prove that he could support his family, he decided to go into business for himself. He used every cent of his and Jennie’s money to purchase a pack of notions, which consisted of handkerchiefs, socks, matches, and other sundries, and made the decision to become a peddler.

Jennie hated the idea of a husband who was a peddler, but she had little choice. Irving’s delicate constitution forced her to stay home and care for him, but Jennie wasn’t too concerned about her husband’s new career, as she had the feeling that Sol’s current vocation would be short-lived. She was right.

One morning, while hawking his wares on a Brooklyn street, Sol was accosted by a group of toughs who had decided to harass this “Jewish character” with the fiery red mustache and bulging backpack. They went after Sol, pulling his mustache, roughing him up, and finally shoving him hard against a nearby wall. The impact ignited one of the matchboxes in his backpack. Instead of ripping off the pack, Sol panicked and ran down the street, his back in flames. Fortunately, onlookers in the windows above heard his cries and doused him with whatever liquids they could find, including buckets of slop.

Poor Sol limped his way home, arriving flushed, beaten, and filthy. Sympathetic, Jennie took him in her arms, then helped him clean up. She realized that Sol would never change, that he would always be that young, inexperienced boy from Vilna who wanted to be a rabbi. She knew from that moment on that she would have to take charge in order to keep a roof over her family’s heads and food on their table.

Through the years, Jennie accepted the job of provider with graciousness, skill, and enthusiasm. She thrived on accomplishment and constantly tried to make Sol feel that he had contributed to her success. Even when she became a wealthy real estate saleswoman, consummating million-dollar deals, she would always hand Sol the checks for deposit—made out in his name. In her own strange way, she had grown to love and honor this man she called her husband.

In 1893 Jennie gave birth to another son, Benjamin “Jack,” a fat little blond-haired baby. Although Jack would be a good student and a fine athlete, he would not be the answer to Jennie’s dream of having a professional in the family, for he would follow in his brother Irving’s footsteps and become an insurance salesman.

While Jack was the picture of health and vitality, Irving, now two, was thin and short for his age. Although Jennie admired and doted on her new curly-haired, blue-eyed son, she drew ever closer to Irving, whom she felt needed her more.

It wasn’t until 1895 that Jennie’s first comedian son came along. On March 17 Samuel “Shemp” Horwitz was born. How his name evolved to Shemp is a family classic. Once again it was Jennie’s European accent that caused the dilemma. When she would call “Sam,” it sounded to others like “Sams” and sometimes like “Shemps,” and among the Horwitz boys and their friends, that strange name stuck.

Shemp was a stubborn child. If he fell or hurt himself or did something wrong and was punished, he would never cry, just tighten his lips, clench his teeth, and rarely utter a sound. As he grew older, this would change, and during his school days Shemp would make up for his childhood silence by becoming the most mischievous and gregarious kid in the neighborhood.

Neither athletically inclined nor a good student, Shemp’s favorite pastime throughout grammar school was making comical faces at his fellow students and his teachers and drawing funny pictures. He was continually clowning and would do anything and everything for a laugh, which resulted in Jennie spending as much time in school as Shemp did.

Curly’s brothers, circa 1900: Moe in front row; second row, left to right, Jack, Irving, and Shemp.

On the day of Shemp’s graduation from elementary school, Jennie and Sol watched proudly as their son stepped up on the platform. As the principal handed Shemp his diploma, he grinned and said, “Students, ladies and gentlemen, this young man did not graduate … his mother did.”

In the year 1897 two momentous events occurred in the lives of the Horwitzes. First, thanks to Jennie’s success in real estate, the family moved to Bath Beach, a lovely summer resort in the Bensonhurst area of Brooklyn. Their new house had a wonderful yard filled with large shade trees under which Sol relaxed and Irving, Jack, and Shemp romped about.

The neighborhood consisted mainly of Irish Catholics, and when the Horwitzes moved in, there were only seven Jewish families living in the area. This was no deterrent to Jennie and Sol. Jennie was excited about the neighborhood’s real estate potential, and Sol was delighted that there was a synagogue nearby.

Bath Beach was to have a tremendous influence on the Horwitz boys. The area had a great many residents in the theatrical profession, and within a mile from Sol and Jennie lived many of the biggest names in vaudeville. The proximity of these stars would contribute to Shemp, Moe, and Curly’s tremendous drive to achieve success in show business.

The second event in ’97 was the birth of Jennie’s fourth son. On a warm day in June, Jennie stopped work long enough to get word to Mrs. Solomon, her midwife, that her labor had started in earnest, and Moses Horwitz pushed his way into the world on the morning of June 19, 1897, and—voila—Jennie’s second Stooge was born.

Moe was sturdily built, with a slim, funny face surrounded by brownish-black hair. He had steel-blue eyes like his mother and weighed in at exactly eight pounds.

Jennie had plans through the years for this, her fourth son. At four, she was sure he’d be a dentist, at six a doctor, at seven a violinist, and at ten a lawyer. In later years, Moe would prove to be her fourth disappointment when, like Shemp, he would also become an actor and then a comedian, both of which were professions that were decidedly not Jennie’s cup of tea.

The family was growing, and it was no easy job raising four sons, catering to a husband, and swinging major real estate deals. To increase the family’s income and enable her to buy more property in the Bensonhurst area, Jennie rented out several rooms in the house to boarders. Desperate for household help, she arranged for Sol’s fourteen-year-old sister, Esther, to come to America from Europe. Strong, robust, and willing, Esther was expected to care for the house, for Sol and the kids, and for a houseful of boarders. This was no easy task, especially with the wild and mischievous Moe and Shemp constantly underfoot.

Esther Horwitz Feldman (Jennie’s indentured servant) with her daughter Emily, circa 1918.

Courtesy of Emily Trager

Bensonhurst Station, circa 1910-1920.

Brooklyn Historical Society

Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. View of east side of Thirteenth Avenue looking north from Eighty-Fifth Street, circa 1910.

Brooklyn Historical Society

Twenty-Second Avenue, the show street of Bensonhurst, circa 1910.

Brooklyn Historical Society

Esther was miserable. She had no room of her own and, on many nights, would curl up on the stairs in an effort to get some sleep. It was catch as catch can, since each rented room meant extra income for Jennie.

In desperation, the homesick young girl complained to her married sister, Celia, who was living in New York City.

As the story goes, on a dark night in 1901, Celia’s husband, Barnet Marx, went to Jennie’s house in Bath Beach and spirited young Esther away. The next day he put her on a train to St. Paul, where she would stay with her older sister.

When Jennie found out that Esther was gone, she was incensed. According to an agreement between Esther’s parents in Lithuania and Jennie, the girl was required to work in the Horwitz home until she paid back the cost of her fare. Jennie accused Barnet of breaking the contract and kidnapping Esther. She brought the matter to court, but the case was promptly dropped, the judge’s reason for his decision forever lost in obscurity.

Moe was four at the time of Esther’s indenture and was never aware of this side of Jennie’s character. In his eyes, his mother could do no wrong, and Moe’s memories of her were all pleasant ones—with one exception: that loathsome time when his mother, who had always wanted a daughter, put his hair into curls. Poor Moe went through hell when he went to school, his funny, freckled face surrounded by large sausage-shaped curls. Naturally, the boys made fun of him, and it was a constant battle to keep his self-respect. This was a traumatic period for Moe and, throughout his life, the only unpleasant memory he ever had of his model mama.

As the years rolled by, Jennie’s real estate business continued to thrive, and she divided her time between buying and selling land and working for charitable causes. Charity for Jennie was a second religion. She helped young couples who were thinking of divorce work out their problems and spent long hours at the Home for the Aged in Brooklyn, where she donated food, clothing, and money and was referred to by the residents as their guardian angel.

Jennie found time for everyone and everything. Surprisingly, she had terrific stamina for a chunky not-quite-five-footer. Her constant cry was “You get out of life what you put into it.” And this remarkable young woman was putting her all into life while the Horwitz family was growing and prospering.

Sol and Jennie should have been happy and content—and maybe they were—but they rarely displayed any emotion.

Jennie’s cousin, Emily Trager, said, “Jennie bugged Sol all the time, constantly reiterating the song title from Fiddler on the Roof. ‘Do you love me?’ was Jennie’s constant cry to Sol.”

And Sol must have heard Jennie’s cry and acted on it, for on October 22, 1903, the same year that the Wright brothers successfully flew their plane at Kitty Hawk, the last of the Horwitz children was born in a hospital in Brooklyn. No midwife this time for Jennie. She was now a woman of means and had young Dr. Duffy, the brother of Moe’s sixth-grade schoolteacher, deliver her new baby. Jennie was certain that the law of odds would be in her favor this time and she would finally give birth to the girl she had dreamed about.

Once again, for the fifth time, she was to be disappointed. Jerome Lester “Curly” Horwitz was all boy. It was only a temporary disappointment to Jennie but none at all to millions of fans yet unborn or, in later years, to Moe and Larry, whose success as the world-famous Three Stooges might never have been achieved with a chubby, bald-headed girl in their act.

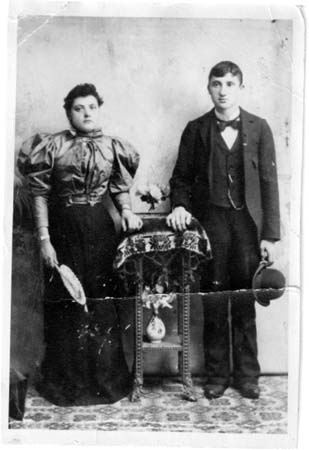

Barnet Marx and Sol’s oldest sister, Celia Horwitz, on her engagement day, 1893, when Celia was living with Sol and Jennie in America.

Courtesy of Stanley Marx