Baby Curly, whom his brothers immediately nicknamed Babe, was a good child and no trouble for Jennie—that is, until his mischievous siblings, Moe and Shemp, showed him the ropes. Their wild, wacky, and inventive behavior reached dangerous proportions when, one day, Moe and Shemp took Curly’s brand-new baby carriage, converted it into a “soapbox racer,” and placed little Curly in it. When Jennie and Sol returned home and found their baby sitting happily astride this mad invention, perched atop a steep hill and poised for a downhill race, they almost blew their gaskets. Years later, Moe realized the danger of his boyhood prank and said, “It was a lucky thing we didn’t kill him.”

Despite numerous scoldings, Moe and Shemp continued their boyish pranks, with Curly always the “fall kid.” On one windy, rainy night in 1908, Jennie and Sol left Moe and Shemp to care for five-year-old Curly. Our three little Stooges were soon ensconced on a seat in an upstairs bay window, with little Babe an eager, receptive audience as they prepared to blow wads of putty out the window with their peashooters. Within minutes, a man appeared on the street below, clutching his umbrella. Curly screamed with delight as Moe blew hard and a wad of putty splattered into the man’s hand, the impact sending his umbrella into the air, where it tumbled away in the wind.

Curly’s delight attracted the attention of his mischievous brothers, and there was no question in their minds who their next victim would be. It was a lucky break for little Curly that Jennie returned home early, just as dead-shot Moe was preparing to shoot a penny out from between her baby’s fingers.

It is interesting to note that, as a child, Curly always took the brunt of his brothers’ havoc, just as he would later on as a grown man during the making of his ninety-seven Three Stooges comedies.

Time was moving onward, and little Curly was developing into big Curly, getting taller and better looking with each passing day. As the youngest of the five Horwitz brothers, he was spoiled, but in spite of this, he was Moe’s favorite, and my father became his second father, filling in for an ever-absent Sol. Moe took Curly to the beach regularly and taught him to swim and play the ukulele and tried his best to get him through school. Curly was a fair student, but unless Jennie, Sol, and Moe prodded him, he rarely attended his classes. All through his school years, Curly’s first love and favorite pastime was playing hooky.

Unlike their kid brother, Moe and Shemp’s favorite pastime in Bensonhurst was putting on plays at the homes of their friends. Curly would usually join the cast and even at this early age had trouble recalling his lines. Taking over as leader of the group as early as 1910, Moe solved Curly’s memory problem and may have been the first inventor of cue cards. He would write Curly’s cues on adhesive tape and stick the tape to his own forehead so brother Babe could read them.

In these neighborhood shows, Curly, at the age of seven, loved to prance about before an audience, egged on by the sound of applause. He was undisturbed by the fact that he was always cast as the female lead. A dab of paint on his cheeks, lipstick on his lips, and an old string mop plopped on his head with the fringe hanging down over his cute, round face, and there was Curly in drag at the ripe old age of seven.

In 1913 Curly spent a bit more time in school, but it wasn’t the three Rs—readin’, ritin’ and rithmetic—he studied. Uh-uh, in Curly’s case it was the two Bs—asketall. He was a terrific player and the star of his school team. At the same time that Curly was addicted to laying up the ball on the school court, teenage Shemp and Moe were going to parties and entertaining their friends. Shemp had matured into a real Chaplinesque clown and would keep everyone in stitches with his wild stories, fast-paced jokes, and kooky antics, with Moe always playing the “straight boy.” It was the favorable reactions of their young friends that encouraged the pair to turn professional, and Moe, always the leader, decided to prepare a blackface act for himself and Shemp in an attempt to break into vaudeville.

Rear yard of a typical Bensonhurst house, circa 1910.

Brooklyn Historical Society

During the weeks that followed this momentous decision, the two brothers smeared their faces with burnt cork and practiced their corny old jokes, while little Curly, left out for the first time, looked on with envy, impatiently waiting for Shemp and Moe’s opening night.

Poor Curly was forced to maintain his patience when his brothers’ entry into show business was suddenly postponed indefinitely. Moe had gotten his first big break and took off for the entire summer. How could he turn down the opportunity to perform on the showboat Sunflower with Captain Billy Bryant? With Moe gone, Shemp was forced to find another partner, and Curly, watching and waiting, wished that it would be him. But such was not the case. He would have to wait many more years for the opportunity to cast his lot in with his talented brothers.

Moe returned from the Mississippi at summer’s end and finally began his professional career in earnest, joining Shemp in their blackface act at the Mystic Theater on Fifty-Third Street near Third Avenue. The two aspiring performers leapt for joy as they signed a contract for the grandiose sum of thirty dollars a week and at last received their billing as “Howard and Howard.”

Curly’s oldest brother, Irving, at age 13 (1904).

On opening day, Shemp and Moe took Curly with them and sat him in the front row, where he waited excitedly for his brothers’ debut. Once again, brother Babe was to be disappointed. Howard and Howard were last on the bill for a specific reason. The greedy theater manager knew how corny their act was, and to clear out the theater for new customers who were lined up outside, he dashed onstage and shouted, “Howard and Howard, up and at ‘em!”

Moe and Shemp charged onto the stage and, just as the manager had planned, the audience left the theater en masse after their first two jokes.

It was a heartbreaking experience for the two, with their only solace the wild, exuberant applause of their brother, sitting alone in the empty theater.

Whether on the stage or in the audience, Curly loved the theater. In his mind his two brothers were superstars, and he was determined to emulate them.

It was 1914. Europe had gone to war, but in America the movies were on their way to becoming a national entertainment and vaudeville was flourishing. The Brooklyn neighbors of Moe, Shemp, and Curly Howard were such vaudeville headliners as Trixie Friganza; Adelaide and Hughes, a top-flight dance team; Charles Dale of the comedy team Smith and Dale; and Harry Fox, who worked with the Dolly Sisters. Added to this rarified environment (and just around the corner from where Curly lived) were the Grand Opera House and the Crescent and Montauk Theaters, where he watched plays whose titles alone quickened his pulse: Ten Nights in a Barroom, The Two Orphans, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and Seven Keys to Baldpate.

Curly longed desperately to be part of this wonderful world of show business, but he felt alone and left out at this point in his life. Moe and Shemp were finally succeeding with their act, mother Jennie was deeply involved in real estate deals and charitable causes that took up most of her time, and his father spent all day chanting the Torah at the local synagogue. It was a period in his life when he found himself marking time, waiting for that day when he would stand on the stage with the footlights shining in his eyes and the audience cheering his performance.

It was 1916 when, at age thirteen, Curly’s first performance before an adult audience finally took place. He strode brazenly onto the stage at his father’s shul to be bar mitzvahed.

Even this event in his show business life was a tough haul for Curly. School, and especially Hebrew school, was not one of his first loves, but for the son of Solomon it was a must, and Curly performed with all the spirit and punch that was later to make him a comedy genius.

Curly at age thirteen, around the time of his bar mitzvah (1916).

Several months after his bar mitzvah, Curly asked Shemp and Moe to go back with him to their Hebrew school at the Congregation Sons of Israel, their alma mater. All three were taught by Dr. Agat, a scholarly old man with very poor eyesight who moved about like an arthritic snail. Always looking for laughs, Curly, Moe, and Shemp decided to play one of their pranks on the old doctor. They snuck to the rear of the classroom and crouched under one of the long wooden benches. When old Dr. Agat entered, all three began raising the bench slowly up and down, like a Ouija board at a séance.

Overly superstitious, the old doctor, certain he was seeing an apparition, rushed off to the rabbi’s study, screaming for him to come see what was happening. When the astute rabbi caught sight of the wooden bench seeming to hover in midair in the back of the room and heard muffled laughter, he caught on at once. Glaring at Dr. Agat, he whispered, “Doctor! Don’t you know those devils yet? It’s the Horwitz boys.”

When these three delinquents arrived home, word of their prank had already reached Jennie, and all hell broke loose. Naturally, all of the dressing down was done by Jennie, the taskmaster, and not by Sol, who throughout his life would never lay a finger on his boys.

Curly (top left) at age fifteen with the members of the P.S. 128 basketball team (1918).

He was the bogeyman that Jennie created, a bogeyman that scared nobody. It is interesting to note that, in this era, catching hell was much more physical than it is today. According to my father, it was usually a hard smack across the face or upstairs and down with your pants, followed by several whacks on the bare buttocks with a strap used for sharpening razors. But Shemp, Moe, and Curly were the lucky ones. Their punishment, though severe, was mild by comparison to that of some of their friends. Other families, at the least display of disrespect from their kids, would crack them over the head with whatever was handy, be it a broom, rolling pin, or mop handle.

The three neophyte Stooges played their next prank against their older brother Jack, whose major goal in life was making money. This was something that Curly just couldn’t understand. Jack was a saver and kept all his money hidden in a sock tied inside his pajama pants. One night, just before bedtime, young Curly noticed with envy the big bulge in his brother’s crotch. Curious, he spied on him the next morning and discovered, with relief, that Jack’s bulging whatsis was in fact his secret sock.

Zingo! Back he went to Moe and Shemp to spill the beans. Jack, a sound saver, was also a sound sleeper. The next night, Shemp, Moe, and Curly tiptoed into Jack’s bedroom and picked him clean. Poor money-mad Jack went bananas for several days searching the entire house and wondering about the grins on his brothers’ faces, until finally our wacky young Stooges returned his money.

Like most teenagers, Curly’s prime interest in life soon turned to the fairer sex. To please the girls, he became a clotheshorse, dressing in the latest fashions of the day. By now, Jennie had consummated many big real estate deals and could afford to clothe Curly in a way she had never been able to do for her other sons. The cut of his jacket, his cap and tie, and the boutonniere in his lapel were the best that money could buy, and week by week his wardrobe grew.

But Curly was never one to think of the future. In Bath Beach when the summer of 1916 came, it was time for fun and relaxation, and Curly would spend his days frolicking amidst sand and surf. Sol would, as always, grab his Jewish newspaper while Jennie would make her business contacts during walks with prospective buyers and sellers in Ulmer Park. The summer of 1916 was also the time that Jennie decided to stake Sol in a business of his own by fulfilling his dream of becoming a manufacturer of ladies’ ready-to-wear. She investigated the potential of this business from all angles, found it sound, and proceeded to take the necessary steps to start Sol on his way. Having no time to help run the business, she finally acquiesced and left it to her husband to make it on his own.

Jennie was not a spendthrift, but when she started charging all of Curly’s new clothes, Sol, who was closemouthed, finally raised hell. Jennie’s answer was a sound one. She wanted to establish credit. If and when hard times came, every door would be open to her. And hard times soon would come, with the crash of the stock market and the start of the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Gravesend Bay in Bensonhurst, Curly’s stomping grounds for swimming and fishing.

Brooklyn Historical Society

Sol bubbled over with confidence and, with full financing from the Horwitz coffers, charged ahead into the world of big business. He was owner, boss, and salesman and quickly found a Midwestern chain-store buyer who agreed to place an order for three thousand skirts. In Sol’s mind, his fortune was made. Moe, who was working at Sol’s factory for the summer, begged his father to look up the buyer in Dun & Bradstreet to be certain he was legitimate. Sol, who could only see good in everyone, responded with “Did you see the man’s eyes? He’s as honest as the day is long.” Ever confident, Sol shipped the three thousand skirts and never saw a dime. Between this major error and the pricing of his skirts at four cents apiece instead of sixty-four cents, he was out of business within months.

Curly, meanwhile, was enjoying the summer, his favorite time of year. July 1916 was hot and muggy, and to escape the Brooklyn infestation of mosquitoes, Curly, who loved to swim, spent most of his time at the beach. Brother Moe, his mentor during these days, was employed on weekends as one of Bath Beach’s assistant lifeguards, and Curly reveled in watching his big brother pull hapless victims from the surf. Throughout his life, Curly never forgot and often related stories about Moe’s heroism as a lifeguard and how Moe and three of his friends eventually joined an act with the Annette Kellerman Diving Girls, which consisted of ten shapely young swimmers. Actually, there were only six Kellerman girls, as Moe and his three friends, dressed as girls, formed the remainder of the troupe. Curly watched enthralled as the “girls,” including Moe, took turns doing thirty-foot dives into a tank seven feet long, seven feet wide, and seven feet deep. Moe and his buddies dove into the water wearing long one-piece bathing suits, caps on their heads, and balls of crumpled newspaper stuffed inside their suits to augment their concave bosoms. After each dive, Curly, who stood tankside, would crack up as the paper falsies dropped down around the boys’ stomachs and they would have to struggle underwater, gyrating comically, trying to push their bosoms back up where they belonged before they emerged to take their bows.

Later in the season, Moe quit Miss Kellerman’s troupe after one of the female divers misjudged the tank and was killed.

For Curly the beach was not only a place to swim but a place to girl watch. He delighted in staring at their cute little bodies in their tight little jerseys, which clung quite pleasingly when they were wet.

This youngest of the Horwitzes was “beach smart” and had a clever method for attracting the attention of the girls. Perched high atop the railing of the pier, at least fifteen feet above the water, he would dive off into about three feet of sparkling white foam. The girls would scream, then ooo and aaah, gathering around Curly, waiting for him to break his neck. When he didn’t, they’d throw their arms around him and congratulate him. He never tired of those hugs and repeated his trick over and over again.

Besides girls and swimming, another love during his teens that definitely affected him in later life was food. Curly ate anything and everything: from his mother’s gefilte fish to those hot, charred potatoes dumped in beach bonfires and given the Irish name “Mickeys.” Life in those heady days was sweet for Curly: strumming his ukulele, plunking out the strains of “Oh, You Beautiful Doll,” eyeing shapely, tanned female bodies in tight bathing suits, and sinking his teeth into charred and blackened fluffy baked potatoes.

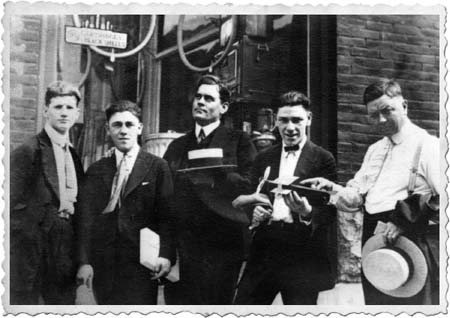

Curly, second from left, and members of the “Bath Beach Gang,” according to Curly’s girlfriend Ernestine Boehm Goldman, who took this photograph at Captain’s Pier.

Courtesy of Ernestine Boehm Goldman

Toward summer’s end, Curly gave up his beach bumming and joined Moe and Shemp on their train ride to the Horwitz farm in Chatham, New York. This 116-acre parcel of land 150 miles from New York City was Jennie’s latest real estate purchase. She not only wanted it for a business investment but felt it would be a healthy place for her sons to spend their summers, away from the heat of the city and far away from that monkey business—show business.

Moe, unbeknownst to his mother, would sandwich in his vaudeville stints with Shemp between his trips to Chatham while his older brother Jack and a professional farmer worked on the farm full-time.

Curly, an animal lover, was fascinated by anything with four legs. On his first trip to the new farm, he took a special liking to a big, fat, curly-tailed pig. This un-kosher beast came with the property, and as soon as Jennie discovered it romping with Curly, she lost no time in selling it, at a discount price, to a neighboring farmer.

Although at home Curly would shirk all forms of housework, on the farm he pitched in with the chores and learned everything from running the cream separator to churning butter and tending the truck garden. Every farm animal became his friend, and he awoke each morning at four thirty to feed them.

Shemp, on the other hand, hated farm work and would rather goof off. He never tired of running around the Horwitz spread in the maddest-looking outfit, which consisted of bright red flannel underwear, an old Continental Army coat, and an early American military hat. Each day would find him playing his favorite practical joke. He would don his kooky costume, strike a comical pose in the middle of a cornfield, and wait for the neighboring farmers to pass by and stare in amazement at what they thought was one strange-looking scarecrow. Of all his big brothers’ many pranks, this one delighted Curly the most.

Another of Shemp and Moe’s capers that Curly loved was watching as his brothers shaved off only one side of their bushy brown beards and then following along as they marched through town. Seeing the expressions on the shocked faces of the staid townspeople never failed to crack up Curly, no matter how many times he witnessed it.

Later that summer, the boys received a letter from Jennie stating that she was coming to the farm for the weekend and wanted them to pick her up at the Chatham Railroad Station. This time, Shemp and Moe decided to try one of their pranks on their own mother. Curly, knowing Jennie’s stodgy, old-fashioned ways, warned his brothers that she wouldn’t appreciate their crazy monkeyshines. His warning went unheeded. There was too much theater in Shemp and Moe, and once these two clowns decided to put on their act, there was no stopping them.

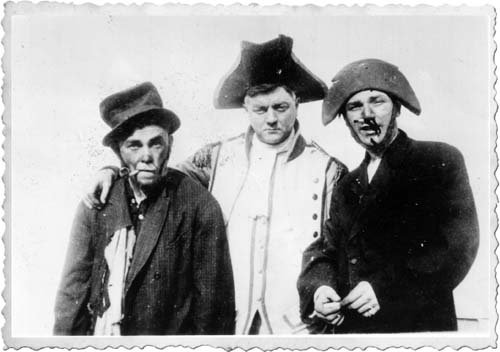

Moe, left, a friend, and Shemp in costume on the Chatham Farm (1916).

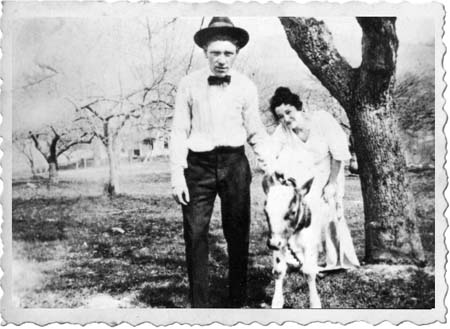

The Chatham Farm. Jack Horwitz (right) aboard a hay wagon with his fellow farmers (1916).

Shemp and Irving’s wife, Nettie, on the Chatham farm in 1916.

Courtesy of Margie Golden

Nettie and Irving on the farm. He is wearing what every well-dressed farmer should wear (1918).

Courtesy of Margie Golden

The Horwitzes’ Chatham farm. Left to right: Curly; Moe; Curly’s dog, King; Jennie; and Sol’s sister Celia (1916).

Jennie and her boys (left to right) Shemp, Jack, Irving, and Moe.

As always, Curly was beside himself with excitement and had difficulty holding back his laughter at the ludicrous appearance of his two crazily costumed brothers as they rode into town on the farm’s “surrey with the fringe on top” to pick up their mother.

When Jennie arrived at the railroad station, she glanced casually at what she was certain were two maniacs standing near the station platform, dressed in red flannels and Continental Army coats with silly-looking black tricornes on their heads. Their half-beards added a final touch of insanity as they stood stiffly by the surrey, each holding a horse by the bridle. There was absolutely no sign of recognition on Jennie’s face as she searched about for her sons. Finally, she heard Curly’s giggles from behind the surrey and realized that these two maniacs were Shemp and Moe. To say that she was shocked would be an understatement. She cringed with embarrassment, her discomfort increasing by the minute as curious townspeople gathered around them, staring and laughing at her two offspring. Livid, she hissed under her breath to Moe and Shemp, “How can you do such insane things—you meshuganas.”

But life on the farm wasn’t all fun and games in the summer of 1916. There were mishaps, the first of which occurred when Curly cut through a nest of yellow jackets while mowing a field. Moe was nearby, and both had to race to the nearest stream and dive in, with the swarm of angry insects in hot pursuit. It was a real-life forerunner of many Stooges antics as they limped back to the farm, soaking wet and covered with masses of swollen red lumps.

Annoying, yes, but a minor mishap when compared to the most traumatic event of this particular summer. It is paradoxical that throughout Curly’s life, as much as he loved animals, he also liked to hunt. One of his prized possessions was his .22-caliber rifle. Unfortunately, it had a hair trigger. While relaxing, Curly placed his gun on his lap, barrel down, between his crossed legs, unaware that the muzzle was resting against the side of his foot. His fingers inadvertently pressed against the trigger. A loud crack rang out and the bullet discharged, shattering the bone in his ankle.

It is a scientific fact that no pain is felt at the instant one receives a gunshot wound. Curly’s pain would come moments later and, although intermittent, would last a lifetime.

Panicked, his friend dragged him home, where an ashen-faced Moe helped his kid brother into bed. Shock had set in, and Curly lay like a corpse, blood pouring from his foot.

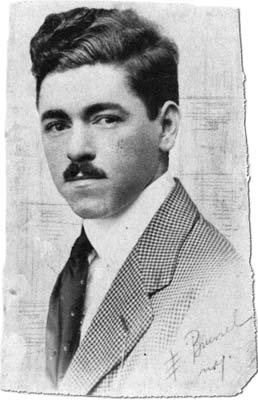

Brother Irving in 1912, in real estate with Jennie.

Jennie, at right, in Bath Beach with one of her sisters. Note ROOM TO LET sign in the background.

Moe, terribly rattled by the sight of all that blood, wrapped Curly’s foot in a towel, carried him into the farm’s surrey, and drove like a maniac to the nearest hospital in Albany, New York.

At the hospital, it was touch and go as to whether Curly would lose his foot. Luck was with him. His foot would not have to be amputated. The doctor recommended immediate surgery that would entail deliberately breaking his ankle bone and then putting his entire foot in a cast until the bones knitted properly. Curly had never been in a hospital before and panicked at the thought of an operation. He instantly rejected the doctor’s recommendation and insisted that the wound be allowed to heal by itself.

Family, friends, and fans would speculate for years to come as to whether Curly made the right choice that night in Albany. The wound did heal by itself without surgery, but the residual effects would leave him with a limp for the rest of his life and would cause him pain if he was on his feet for extended periods of time. But Curly was a trouper and never allowed his handicap to interfere with either his work or his play.

The traumatic summer of 1916 passed and was followed by an uneventful fall and winter. Then, in the spring of 1917, the United States declared war on Germany. Curly was fourteen at the time, struggling to graduate from grammar school, while Moe and Shemp were performing their comedy act for both the Loews and Keith circuits.

Working for two vaudeville circuits at the same time was a major no-no, as there was an unwritten agreement between the circuits that if you worked for one, the other would not hire you. Shemp and Moe, ever the inventive pranksters, got around this no-no by disguising themselves with the aid of makeup and performed a blackface act for Keith and, under another name, a whiteface act for Loews. They got away with this trick for months, until Shemp’s number was called and he was drafted into the army. Moe found himself unemployed—but not for long. Shemp was discharged after only a few months of service when the army discovered he was a bed wetter. Always a sensitive young man, and a lifelong scaredy-cat, Shemp was terrified by the thought of soldiering in a shooting war and was greatly relieved when Uncle Sam rejected him. Throughout his life he thanked God for supplying him with a weak bladder.

While the Horwitz family was celebrating Shemp’s safe return from the wars, Jennie, ever the astute real estate businesswoman, received an offer for the Chatham farm that she couldn’t refuse. But, as always, her children came first, and especially her baby Curly. The escrow stipulated that the new owner could not take occupancy until the fall of 1918, allowing Curly one extra summer on the farm with the animals he loved.

The summer of 1918 found Curly enjoying life by helping with the harvesting of the wheat, corn, and buckwheat crops, and especially loving every minute of tending the farm’s animals. Moe and Shemp were also there for this last summer, and they were later joined by their other brother, Jack, who married his boyhood sweetheart, Laura Brukoff, and spent his honeymoon on the farm. Jack later moved to Laura’s hometown of Pittsburgh, where he eventually got a job with the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company and rose to district manager. Jack would never be an actor, and his only link to show business would be selling bundles of life insurance to his three famous brothers, Moe, Shemp, and Curly.

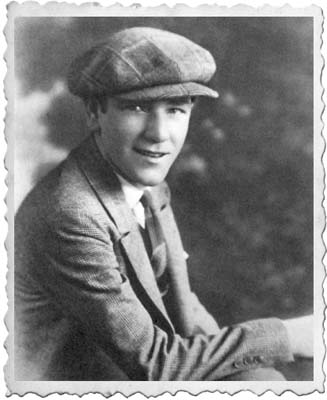

Shemp, returned from the war (1917).

When the war ended in November, life was running smoothly for the Horwitzes. Jennie’s real estate business was booming while Sol was happy and serene, spending most of his time in prayer and, thanks to Jennie’s empathy, made to feel as though he were part of her success. Irving, the oldest of the Horwitz offspring, was twenty-nine, happily married, and a successful insurance man like his younger brother Jack. Shemp and Moe were back in show business, moving up the entertainment industry ladder in two circuits with their black- and whiteface acts, and Curly, now sixteen, had crossed over the threshold from boyhood to manhood.

All through my research on Curly’s boyhood, I was dying to find someone who actually went to school with him. I knew, without a doubt, that someone was out there somewhere, but I was aware that the odds of my finding him or her was like finding a needle in a haystack.

Then on April 13, 1985, my husband received a letter from an Ernestine Goldman, who mentioned that she had seen some publicity about a new movie on the Stooges that Norman had proposed, and this had given her the impetus to write to him. The next line in the letter jumped out at us. It read, “The mention of the Stooges brought back fond memories of Jerome (Curly). We went to school together when he was one of the Horwitz boys.”

Need I say I was ecstatic? It took over a week to get in touch with Ernestine, as she had gone to the hospital for tests. When she finally answered my phone call, I was surprised to hear the lovely voice of a youthful, sharp eighty-year-old. Here is what she had to say:

The Marguerite Bryant Players stock company (1919), Oakford Park, Pennsylvania. Moe, second from left; Shemp, second from right.

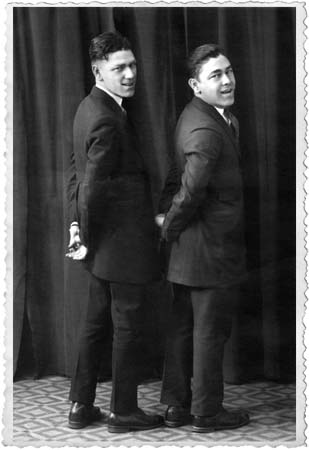

Moe and Shemp about to start their careers in vaudeville, July 19, 1919.

Shemp and Moe onstage during their act as “Howard and Howard” (1919).

Ernestine Boehm Goldman

April 19, 1985

Courtesy of the subject

JOAN: So you knew Curly and his brothers between 1916 and 1919?

ERNESTINE: I was more friends with Curly than the other brothers. They were older. Curly’s name wasn’t Curly in school, it was Babe.

JOAN: Do you mind telling me what year you were born?

ERNESTINE: 1906.

JOAN: And your maiden name?

ERNESTINE: Boehm. My name was Ernestine Boehm, but everyone called me Ernie.

JOAN: What street did you live on in Bensonhurst?

ERNESTINE: Eighty-Fifth Street off of Eighteenth Avenue. I was at 1827, and Curly lived on the same block—a few houses down.

JOAN: Then Curly was going to school in Bensonhurst?

ERNESTINE: Yes, that’s right. P.S. 128.

JOAN: You were born in 1906—that would make you how old when you knew Curly?

ERNESTINE: I must have been about—oh, maybe fourteen, fifteen, sixteen. Babe would come over with the boys, play ball, and wait for me. They would come over on Sunday. I was working at a real estate company. They used to come over to my house, too, where I lived with an aunt of mine. And years later—I recall—when I got married. It was about a week before my wedding. My husband [to be] and I were walking on Eighty-Fifth Street, and all of a sudden we see him [Curly] coming down the stairs of our apartment house. We asked him where he was coming from, and he said, “I’m here for your wedding.” And we said, “We’re not going to be married until next week.”

JOAN: [Laughing.] What else do you remember about Curly?

ERNESTINE: What can I tell you? We used to play together. I recall him sitting on the running board of the cars, playing his ukulele.

JOAN: How long did you go to school with Curly?

ERNESTINE: I went to school with Babe mostly in the later grades [of public school].

JOAN: Did Curly graduate?

ERNESTINE: He sure did—that I know—yes.

JOAN: Did he go on to high school?

ERNESTINE: That I don’t know. We saw a lot of each other in the early years, and after that we didn’t.

JOAN: What were his parents like—that is, if you knew them?

ERNESTINE: They were real elderly parents [when Curly was sixteen Jennie was fifty] and very religious.

JOAN: She was said to be very stern and very efficient.

ERNESTINE: Oh, yes. She had the upper hand.

JOAN: When you knew Curly, did his parents spend time with him?

ERNESTINE: He was on his own mostly.

JOAN: What was Curly really like?

ERNESTINE: Full of the devil. Full of the devil but a nice guy. I remember going to the movies with him once—with some friends—and he put his arm around my shoulder, and all of a sudden his hand went down a little bit. I took his hand and I threw it off, and I walked out of the movies and he followed me.

JOAN: How old was he then?

ERNESTINE: About sixteen.

JOAN: He became quite a womanizer. He was married four times.

ERNESTINE: Oh my God. Really? Oh, I’m glad I didn’t marry him! Oh my goodness!

JOAN: He had two children with two different wives.

ERNESTINE: Babe? Oh, you’re telling me something I never knew.

JOAN: You’re going to be fascinated by this book. [Pause.] He was said to have been good at sports—was it basketball?

ERNESTINE: Yes. And baseball, too.

JOAN: Would you say he was a happy kid?

ERNESTINE: Oh, yes.

JOAN: Was he close to his brothers?

ERNESTINE: Yes, but they were busy all the time.

JOAN: Now, if you look back at young Curly, what stands out in your mind?

ERNESTINE: I … don’t know…. I just liked him. Yes—I put up with him. [Pause.] He lived right on the block. It was bu-dee-ful.

I was really excited when I hung up. I felt as though I had been able to go back through the years and get an honest glimpse—even though a small one—of Curly the teenager from a woman’s point of view.

And Ernestine’s words, “I just liked him,” when I asked her what stood out in her mind about Curly made me realize that even in the early days, Curly must have had that special charm.

And Curly had plenty of charm as he matured into a good-looking, curly-haired young man. He was out of school, and having no professional skills, his dream was to follow in the footsteps of his two successful brothers. Knowing his mother’s disdain for the acting profession and her constant aggravation over two of her sons frolicking about as thespians, he fought his desires and once again turned all his energies to the girls. Using skills that were honed by his brother Moe when the two played their ukuleles and harmonized together on the beach, Curly turned every ounce of his creativity to the fairer sex, singing and dancing his days and nights away as an endless stream of pretty young damsels clung to the arm of this cute, talented young guy from Bath Beach.

Curly’s innocent, happy teens were about to segue into his twenties. Respecting his mother’s wishes, happy-go-lucky Curly shelved his show business aspirations, never dreaming that one day he would become world famous, coining such catch phrases as “n’yuk-n’yuk” and “why soitenly,” or that decades after his untimely death he would become a cult hero to millions of devoted fans who would imitate his every mannerism.

But this was still 1919, and as the teens on the calendar also drew to a close, Curly was moving closer to the Roaring Twenties, which would rumble with thunderous applause for Shemp and Moe but bring the Great Depression to the Horwitz family as well as to America and the rest of the world.