Without a doubt, the major event in Curly’s life during the ’20s was his first marriage, the union between Curly and his mysterious bride that for decades was a mystery to my family and me. Now, thanks to the research required for this book, it is finally becoming somewhat less obscure.

I don’t recall when I first heard that my uncle had married in his youth and that my grandmother had broken up the marriage shortly after the wedding. I was probably in my teens and never really paid much attention to this bit of family gossip. The one thought that stuck in my head at that time was that if Jennie was able to make her son leave his bride after several months of married life, then Curly must have been very young.

Not until I was researching for my first book, in 1981, did I attempt to locate Curly’s marriage license, hoping to find out the mystery girl’s name. I spent a lot of money and came up empty-handed. Today, I am still not certain what her name was, but I have a bit more information about her that I pieced together after questioning members of my family.* After extensive interviews, some of which were with distant relations whom I had never even met, I came up with a few more brushstrokes in my attempt to clarify a very fuzzy portion of the canvas of Curly’s life.

My presumption that Curly’s mother instigated the divorce because her son was too young appears to be wrong. I was floored when I discovered that Curly actually married his first wife when he was in his midtwenties.

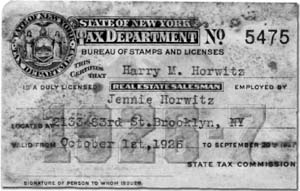

Although Jennie still had Curly completely under her thumb in the early ’20s, he saw very little of her or his brothers Shemp and Moe during that period. Jennie, in 1922, was fully occupied with her real estate business, and Shemp and Moe were on the road, appearing in vaudeville theaters across the country.

During their absence, Curly lived for letters from Moe, who always kept in touch, sometimes phoning and telling his kid brother the details of the exciting things that were taking place in his career. News that Moe had met his old friend, Ted Healy, at the Prospect Theater in Brooklyn and that he and Shemp had been asked to join Ted in his vaudeville act gave Curly mixed feelings. Although he was thrilled about this big break in his brothers’ careers, he also had pangs of envy about not being a part of their show business success. Life was dull for Curly in 1922. His mother had made plans for him to go back to school and learn a trade, but Curly had absolutely no interest in soldering pipes or connecting wires, which were far cries from his dream of being on the stage, singing, dancing, acting, and feeling the exhilaration that came with the thunder of applause that he was certain he would get one day.

The years crept by at a snail’s pace, as if time were passing by in slow motion. In 1924 Curly was twenty-one and, although no longer a minor, was still suffering from the pressures brought about by a domineering mother who still considered him her baby. He didn’t feel like a man, and although his mother’s domination was beginning to get to him, he was incapable of breaking away and upsetting her.

In the winter of 1924, Curly’s beloved beach was too cold, and he would have to wait until summer to find any diversion there. To fill his empty days and pass the time, he would polish his parents’ Hupmobile over and over. He envied his friend Lester Friedman, who was a bookworm and could bury himself in a novel and never come out, but reading for Curly had always been a chore, and as much as he tried, he could not find an escape in literature.

Curly spent those long winter days looking forward to the nights. Night was when he came alive. He was an excellent dancer, and evenings usually found him at Brooklyn’s famous Triangle Ballroom, his favorite nightspot. Spectators would often stare in admiration at his lightness of foot and wonderful sense of rhythm, and although this was a far cry from his dreams of the stage, at least it helped suppress his hidden desires.

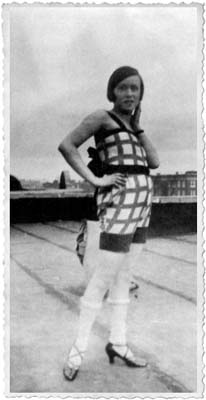

I tried to picture him in his favorite haunt. I let my imagination take over, and in my mind I could almost see the crowded dance hall, with its flashing lights, and hear the ’20s music. Curly is there, handsome, twenty-one years old with wavy chestnut-brown hair, gliding gracefully across the dance floor. He is dressed to kill in the latest fashion, and there is a pretty girl in his arms, wearing a very short dress with the tops of her stockings rolled neatly just below the hemline. Could this be the mystery girl whom Curly would marry one day? The secret still remained hidden. Ted Gell, an usher at Moe’s wedding, described her as “in her late twenties, attractive, and definitely not Jewish.” My cousin Bernice, on the other hand, described her as “definitely Jewish, a cute little thing with her hair bobbed and wearing a short dress of the period.” Another cousin, Emily Trager, said, “She was an older woman, a friend of Jennie’s.”

Among the diversity of descriptions, I am certain of only one fact: she was definitely pretty, since throughout his life, Curly’s taste always ran to attractive women.

I thought about the many descriptions of Curly’s first wife, and they brought me back to my reveries and to one of those many nights that he spent at the Triangle Ballroom. George Raft was a Triangle regular, and one wonders if he was there that night, watching Curly hold his pretty partner and expertly maneuver her through the steps of the Charleston. Did Curly lean over and croon the latest ballad of the day softly into her ear? Did he suddenly stop dancing and stare into her eyes with thoughts in his mind of running away with her, away from Jennie’s control?

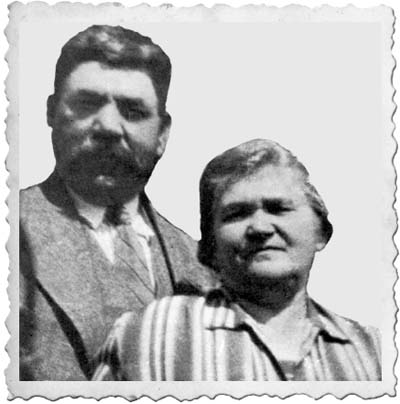

Curly’s parents, Sol and Jennie, in 1929. A photo that Curly cut out and mounted on wood.

For a brief moment I was there with my uncle, watching, and then I snapped out of my fantasies and realized that I’d give my eyeteeth to interview this young lady—even though she would be in her eighties.

I stopped and shook myself out of dreamland. Thoughts raced through my mind. How could this young man in his twenties, with the girl of his dreams in his arms, have had to live his life according to the dictates of his mother? Then I recalled my cousin Dolly Sallin’s words: “Jennie, on the one hand, had a sweet way about her, but when she would say, ‘This is what you do,’ that is what you did. She ruled her family [and especially Curly] with an iron hand.” Dolly continued, “God! It took so many years for each son to transfer their love and decision making to their wives. Even my father [Jack] had problems. In an argument between Jennie and my mother, he would always take Jennie’s side. It took years for him to cut the cord.”

After Dolly’s words, I fully realized that poor Curly was Jennie’s “baby,” and it must have been next to impossible for him to escape the clutches of my grandmother’s iron hand.

In the summer of 1924, when Jennie finally discovered that Curly was going out regularly with one particular girl and spending a great deal of time dancing the night away at the Triangle Ballroom, she decided to spirit him away from Brooklyn, insisting that he join her and Sol on their annual trip to the mountains.

In July mother, father, and son left in the family Hupmobile for Saratoga Springs, an exclusive resort in upstate New York. Jennie and Sol were addicts for the waters of Saratoga, which were touted as wonderful for the skin as well as having superlative laxative powers. To them their yearly trip to Saratoga was a must for both its internal and external cleansing properties.

After several days of drinking the purifying waters and watching with boredom as the elderly doddered about through the park-like grounds heading for restrooms, poor Curly began to feel that he was living a nightmare. There was nothing for a young man of twenty-one to do at Saratoga: no ocean, no dancing, no sports—just an army of old people and a hot, smelly pool of mineral water. To make matters worse for frustrated Curly, there was Jennie, constantly nagging him to drink the water. “Drink, drink,” Jennie would say. And, to shut her up, Curly drank.

Saratoga water was powerful stuff, and after several days at the resort, Curly discovered that its cathartic effect worked like a combination of dynamite and Milk of Magnesia, which forced him to carry a briefcase filled to the rim with toilet paper.

One day, Jennie, Sol, and Curly stopped at a bench to rest, when suddenly the volatile effects of the water hit Curly. He grabbed for his briefcase and raced wildly to the nearest restroom. Moments later, he exited, then stopped dead in his tracks. There was no beach in Saratoga Springs, no dance bands, but there was one adorable young lady chatting with Jennie and Sol.

Far from shy, Curly rushed up to them and introduced himself. After several minutes of conversation, he noticed the girl grinning from ear to ear and then slapping her hand to her mouth to choke back her laughter. Poor Curly looked down, and suddenly his cheeks turned red with embarrassment. Trailing out from his briefcase and back in the direction of the restroom were several yards of snow-white toilet paper. With the regal nonchalance of a king picking up his train, Curly reeled in the toilet paper and, without missing a beat, tucked it neatly back into the briefcase. The girl, impressed with his pantomime, could do nothing but say yes when he asked her for a date.

Curly’s mother, real estate tycoon Jennie Horwitz, on her annual visit to Saratoga Springs—where Curly ran into big problems (1924).

Upon his return to Brooklyn at summer’s end, Curly found a letter from Moe, and his face lit up as he read:

Dear Babe,

Being on the road with Ted and Shemp is hectic; but life is treating me well. I have great news. I met a lovely, young lady on the beach last year. Maybe you remember her, Helen Schonberger. She was the one with the great legs. She walked over to us when we were playing the ukulele on the beach—cute, short, dark hair and I’m going to marry her. We have set a date for the wedding, June 7th. I’ll call when I get back to give you more details.

Your loving brother,

Moe

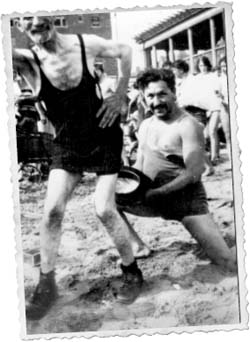

Moe, relaxing between vaudeville performances at Brackenridge Park in San Antonio, Texas (1924).

Although elated at the news, Curly couldn’t quite recall a Helen. He searched his mind, trying to remember her, but there had been so many pretty, cute, short, dark-haired girls with great legs during those wonderful beach days with Moe that he just couldn’t place her.

Moe and Helen’s wedding was held on June 7, 1925, at the temple Congregation Sons of Israel—that same temple where the Horwitz boys had raised so much hell. Moe had ten ushers in attendance, and four of them were his brothers. He didn’t want to hurt anyone’s feelings, so there was no best man.

That same year, Curly received another bit of good news: his brother Shemp was also getting married—to a girl he knew from the neighborhood, Gertrude “Babe” Frank, the daughter of Jennie’s favorite Bensonhurst builder.

Curly was now alone, the only bachelor among the five brothers. Then, in 1926, Moe abandoned show business and returned to Brooklyn with his bride, renting an apartment on Avenue J near Coney Island Avenue. My mother, Helen, was pregnant, and my father had dropped out of the act because touring with Ted Healy and Shemp took him away from his new wife for long periods of time.

Helen Howard, Curly’s future sister-in-law (1923).

Helen on her wedding day, in full regalia (1925).

In Brooklyn, with Jennie’s help, Moe went into the real estate business. He bought several pieces of property in Bensonhurst and hired some of his old classmates as subcontractors to build several homes on speculation. Curly pitched in, hauling lumber and doing odd jobs, enjoying having something to fill his days. Upon completion of the houses, Moe discovered that he had built them too well. They were just too expensive for this Brooklyn neighborhood, and he found them next to impossible to sell without losing his shirt.

Moe and Helen on their honeymoon (1925).

Moe abandons showbiz to be with his new wife, and Jennie helps Harry (a.k.a. Moe) to get his start in real estate.

Helen and Ted Healy meet for the first time, in 1927, after Moe failed at real estate and rejoined Healy’s act.

On April 2, 1927, Moe’s first child—the author—was born, and Curly was the first to see the new baby. His visit that day had a dual purpose: First, to play uncle to his new little niece, and second, to cheer up Moe, who had called that morning to inform him that the bank had taken over his unsold houses and he would have to file for bankruptcy.

In the months that followed, Curly’s visits to Moe’s apartment increased in frequency. He enjoyed seeing his brother and his wife and holding his new little niece in his arms. Later, in 1929, envying Moe’s domestic life, he made his first major decision in life and, on impulse, without consulting his mother, rushed to a justice of the peace and married his mystery woman.

Things went well for several months, until circumstances forced Curly to tell his mother about his secret marriage. He had found out the hard way that two could not live as cheaply as one and was forced to come to her for a loan. When Jennie heard the news, she raved and ranted, shouting at Curly that she would support him but not his wife. As the weeks progressed, Jennie barely tolerated her newest daughter-in-law. Then, determined never to borrow from his mother again, Curly got his first job in show business. Although it was only part-time, he was hired to be guest comedic conductor for Orville Knapp’s band.

One can imagine Jennie’s reaction as she watched her son on the podium in front of the orchestra, his back to the audience, dressed in a swallowtail coat, its exaggerated black tails dragging across the stage floor. Then, as Curly moved his arms gracefully and waved his baton, the coat, which was made to self-destruct, ripped in half down the back. A few more waves of the baton and his pants split in two, and there stood Jennie’s Curly, conducting the band in long underwear whose drop seat was held up by a giant safety pin. The band gave out with a dramatic drum roll, cymbals crashed, and amidst a roar of laughter, Curly took his bow, pants still draped around his ankles. As he comically hobbled off the stage, he glanced back to see what effect his routine had had on his mother—and there was Jennie, her expressionless, scowling face frozen like the head of the Sphinx.

Two weeks later, when Curly emerged from the family’s traditional Friday-night dinner, his face was ashen. The actual words that were spoken that evening at the Horwitz house will forever remain a mystery. What is known is that Jennie had somehow convinced Curly to divorce his new wife.

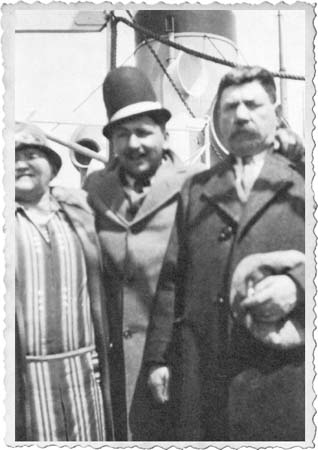

Jennie must have felt some remorse for the trauma she had forced upon her son, for she invited Curly to join Sol and her on an extended European vacation. She would be visiting her old hometown in Lithuania and agreed to let Curly spend several weeks on his own in Paris. Always one for a bargain, Jennie was actually killing two birds with one stone. She was hopeful that in Paris Curly would forget about both of his loves—his ex-wife and the stage.

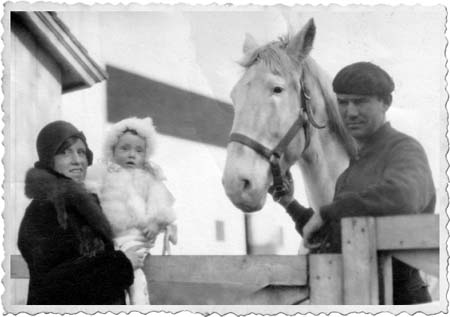

Curly, flanked by his mother and father, aboard the ship on his way to gay Paree (1929).

Curly’s days in France were filled with fun and games. Pretty girls were everywhere, and not always the nicest girls. And Curly was getting an education that Jennie would neither have dreamed of nor approved of.

Paris was also a theatergoer’s delight, with world-famous nightspots such as the Moulin Rouge and the Lido, which were filled with wonderful music and beautiful French girls. Brooklyn was never like this, and Curly reveled in the Parisian nightlife. Paris fashions intrigued him, and his mustache, which was on the bushy side when he left the States, was clipped and waxed at an elegant Left Bank salon.

During his stay in Europe, Curly had time to reflect upon the state of his life. With one marriage under his belt and a taste of world travel, there would be no holding him down. Jennie did not know it yet, but she had lost him. She would always have her son’s love and respect, but from Paris on, he would be his own man—at least until he joined Moe in 1932, and then Moe would take charge.

On his return from Europe, Curly rejoined Orville Knapp’s band. It was 1929, and Moe, after losing more than twenty thousand dollars in his real estate endeavors, was back in show business. He and Shemp were starring on Broadway with Ted Healy in A Night in Venice. Curly hated working in Knapp’s band and was champing at the bit to quit and join Moe and Shemp. He was making a pittance as a comedic conductor and, never able to hold on to his money, constantly had to go to his mother for help.

Helen with daughter Joan and Ted Healy on his Darien, Connecticut, estate during rehearsals for A Night in Venice (1929).

Although Jennie had her faults, she was always generous when it came to her baby. Occasionally, at the Horwitzes’ traditional Friday-night dinner, she would put a hundred-dollar bill under the dinner plates of each of her boys so that she could help Curly without making him feel as though he were the only failure among the five brothers.

One day, with one of those hundred-dollar bills burning a hole in his pocket, Curly decided to spend a week at his brother Jack’s home in Pittsburgh. He went on a shopping spree and loaded up with gifts for Jack’s wife, Laura, and their three kids, Rhea, Bernice, and Norman.

Curious, and wanting more details about Curly’s visit to his brother Jack’s home and other details about his life in the ’20s, I telephoned my cousin Bernice Herzog for an interview on the subject.

Bernice, who was present during Curly’s Pittsburgh visit, is the daughter of Curly’s older brother, Benjamin “Jack” Horwitz, and Laura Brukoff. She was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1919, graduated from Pennsylvania State College of Optometry, and had been practicing her profession in the Pittsburgh area for over forty years. She was married to Dr. Marvin Herzog, also an optometrist. The Herzogs had two grown children, Lynne and Jeff.

Bernice Herzog

January 1984

Courtesy of the subject

JOAN: Do you recall anything about Curly in the early days?

BERNICE: Uncle Babe [Curly] lived with us for a while in the late ’20s. He was very fond of my mother—either because she and dad married on his birthday or because my mother and Jennie battled over real estate deals and my mom usually won.

JOAN: How did Jennie feel in those days about Moe and Shemp being in show business?

BERNICE: Jennie thought she was being cursed because her two boys were on the stage and her “baby” was straining at the bit to join them. In fact, to get Uncle Babe away from the theater, she sent him to Europe—I think he spent most of his time in Paris. When he returned, he was even more handsome than before, with his dark, wavy hair and very French waxed mustache. This is the time he came to Pittsburgh.

JOAN: Can you recall any funny stories related to Curly’s visit?

BERNICE: Yes, one comes to mind. Jennie had two married sisters in Pittsburgh. One had thirteen children, the other six, so Curly had plenty of cousins who were his contemporaries to horse around with. I recall it was New Year’s Eve and Curly and his cousins had gone to a party. When I came downstairs the next morning I found Uncle Babe sleeping in a chair. When I saw his face, I almost screamed in shock. One side of his upper lip was shaved down to the skin, leaving only half of his wonderful waxed mustache. When he awoke, he had no recollection of the prank that had been played on him, but he was a good sport and laughed and laughed.

JOAN: What did Curly do to keep busy? After all, he was out of school.

BERNICE: At this time in his life Babe was dying to be in the public eye, like his brothers, so he spent a lot of time in the Jewish restaurants doing what he did best—eating. One day when he was clowning around, telling jokes and singing, Joe Hiller saw him. Hiller, the owner of a large music store, hired Curly then and there to plug his songs. Curly loved to sing, and I recall he would go into Hiller’s store, grab a piece of sheet music, and really stop traffic.

JOAN: Do you know anything about Curly’s first wife—the mystery woman who married him in the late ’20s?

BERNICE: I saw Babe’s first wife on a visit to New York. She was a cute, short little thing with a real ’20s hairdo. You know, with short sides and bangs—a real flapper type. Shortly after this meeting, my family went back to Pittsburgh, and I heard them talking about the “annulment.” As I recall, Curly and this first wife were together for only a short time—maybe a month. Grandma was pretty influential, and although she always claimed she had his marriage annulled, I think he was divorced and Jennie was ashamed to let anyone know. In those days, among orthodox Jews, a divorce was a disgrace.

Curly clowns around with an unidentified elder.

Courtesy of Dr. Bernice Horwitz Herzog

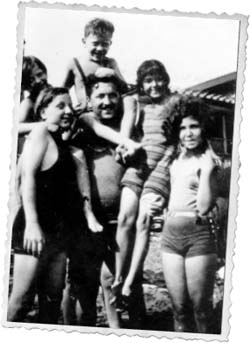

Curly with a full head of hair on his Pittsburgh visit in 1929, with cousins: Norman on his shoulders; Bernice, front left; Dolly, rear left; Margie, rear right; and Ruth, front right.

Courtesy of Dr. Bernice Horwitz Herzog

JOAN: I heard from one of the ushers at Moe’s wedding [Ted Gell] that the girl may have been Gentile. I heard from my cousin Emily that she was a much older woman and a friend of Jennie’s.

BERNICE: As far as my recollections go, the girl was Jewish. I did hear that she was older, but Jennie wasn’t mad about anything other than the fact she was going to lose him. Grandma broke that up, and she also had something to do with Babe and Elaine breaking up. I think Elaine’s mother and [our] grandma got together. They both butted in too much.

JOAN: So Jennie was a tough woman and a meddler?

BERNICE: Oh, very much so.

JOAN: Can you tell me more about Jennie?

BERNICE: Jennie was vicious when it came to her real estate business. She and my mother were constantly at odds and in competition regarding their business deals, and my father [Jack] was in the middle. Jennie was strange. She just didn’t want to let her children go, and even though my dad was married, he had to visit his mother every morning at breakfast time and again at dinner time. It was crazy. First, he ate breakfast at our house, then breakfast with his mother. Then he would stop off at Jennie’s for dinner before going home to eat dinner at his own house. Very often my dad, in all innocence, would tell Jennie about a real estate deal my mom was working on, and she would take the customer away. I don’t know why, but Curly—like all his brothers—worshipped his mother.

JOAN: I have had various descriptions of Curly and what his personality was like. In the ’40s he was described as being quiet—almost dull on the set. Can you recall what he was like when you knew him back in Pittsburgh?

BERNICE: When Uncle Babe stayed with us, he was never quiet, certainly not dull. Dinner time was great fun, as he was very gregarious. He was always “onstage” and loved to be funny.

JOAN: Was he ever vulgar?

BERNICE: Never around us—Dolly, Norman, and me. Of course, we were young children. I don’t know how he was with the rest of the family.

JOAN: Do you think that Curly was as close to his parents as Shemp and Moe?

BERNICE: I’m sure he loved them, but he may not have been as attached to them, because he was the youngest, and at that time Jennie was getting to be a very busy woman.

JOAN: My father painted Jennie as the perfect mother, almost a saint, while others in the family have been less than kind. What were Jennie and Sol really like?

BERNICE: Grandma was the businesswoman. She was volatile while Grandpa was serene. He walked behind her, hardly able to keep up. Even though she had short legs and he long, she scurried along like a jackrabbit. She was like a mother dragging a child; she would pinch his upper arm and say, “Come, Sol.” And you can bet he did! I recall that Grandpa, when he was alone, would always sit in the dark. [He was a frugal man and hated to waste electricity.] He did have a hearty laugh, and when something struck him funny, he shook like a bowl of Jell-O.

JOAN: How did Curly get along with his brothers?

BERNICE: All the boys watched over Curly. When he was very young, it was because he was the baby of the family; when he was older, it was to protect him from his surroundings. And your father did control him for a long time. Guess he always felt the “big brother” and was aware of Curly’s sensitivity and lack of business acumen.

JOAN: Curly loved cars. Did he have a car in the old days?

BERNICE: He didn’t have a car of his own in the early years but he did drive a big Hupmobile which was supplied by Jennie and Sol. Neither of them drove, so I imagine Curly chauffeured them around. He picked up many of the Bensonhurst girls while driving. He’d lean out the window and yell, “Hi, Toots!”

JOAN: Was Curly a well man in his early years?

BERNICE: Yes, Uncle Babe was never ill. He did have bad eating habits. Ate much too much and much too fast. I picked up this bad habit of his; he used to want to race with me during dinner to see who could finish first. Guess who won?

A month after interviewing Bernice, I located another cousin, my uncle Irving’s youngest daughter, Margie Golden, whom I hadn’t seen in over twenty-five years. It was only through some clever detective work and the help of the California Dental Association (Margie’s husband, Harold, is a dentist) that I found out she was living within a mile of my house. I called my cousin Margie, who agreed to meet with me at her house, where she would answer my questions about our uncle Curly.

Margie Horwitz Golden

May 9, 1985

Courtesy of the subject

JOAN: Could you tell me what Jennie was like?

MARGIE: Grandma was the most wonderful—the best. The best grandmother anybody could have.

JOAN: What year was this?

MARGIE: I was about seven or eight. It must have been about 1929. It was the time that Jennie and Sol went to Europe for four months. And Curly went with them.

JOAN: I heard Jennie was going to Lithuania to see her family.

MARGIE: Yes, and she went to the baths in Baden-Baden.

JOAN: Through the years, I recall my dad saying that your father, Irving, was Jennie’s favorite. Do you have any idea why?

MARGIE: He was a Teller vom Himmel.

JOAN: What does that mean?

MARGIE: A dish from heaven. That was what he was to her.

JOAN: Was this because he was the first son?

MARGIE: No, Jennie was very poor at the time—doing piecework, sewing little boys’ pants in a basement. And Irving was born at a time when they were unable to give him things.

JOAN: I thought she might have cared for him more because he was frail.

MARGIE: He was delicate. I recall a story about Jennie and my father. One time Jennie was lying in bed with baby Irving. This was when she and Sol were living in an apartment. She fell asleep, and when she awoke, my father had crawled out of the bed and onto a ledge outside the window, which was several stories up. He was perched precariously, about to fall. Jennie crawled on all fours around the room toward the window, never saying a word, afraid she’d scare him. When she reached my father, she grabbed his foot and pulled him in.

JOAN: Goodness! How old was he then?

MARGIE: He was about two years old.

JOAN: I’ve heard several stories about our grandmother from members of the family. One cousin said she was a martinet.

MARGIE: She was quite a woman. Very tough. She used to send me to the store, and before I left, she would say, “Margie, you tell the man that Jennie Horwitz sent you. Remember, you don’t have to pay anything. He’ll trust you. Just tell him it’s for Jennie Horwitz.” And they trusted her.

JOAN: And Grandpa … was the quiet one. And definitely not a businessman.

MARGIE: He just collected the rents for her. Collected them and gave them to her. Everything was hers.

JOAN: Can you recall any humorous stories about Jennie and Sol?

MARGIE: Oh, yes. I remember going to Shemp’s house with Grandma and Grandpa. And I’ll never forget—Shemp and his wife, Babe, had bought live lobsters, and you know religious Jews are not supposed to eat shellfish. And so Shemp hid them by dumping them in the stall shower. We were all sitting in the kitchen, and Grandma and Grandpa could hear the click click of the lobsters’ claws. And there was Shemp trying to cover things up by telling them all kinds of crazy stories, insisting it was mice.

JOAN: Did she ever see them?

MARGIE: [Laughing.] Oh, no. She would have died.

JOAN: My father said Jennie was a saint, and all the sons felt this way about her. But other members of the family thought of her as a shrewd, calculating businesswoman.

MARGIE: That was true, but she did everything for her children. She was a devoted mother.

JOAN: When Curly was born, Jennie was completely wrapped up in real estate. Did she have time for him?

MARGIE: He was on his own. He wouldn’t listen to anybody.

JOAN: I heard Curly was married for the first time in New York in 1929. Can you give me any information about his wife?

MARGIE: I remember her. She was a very pretty girl, about two or three years younger than Curly.

JOAN: How could Jennie go to her son and make him divorce his wife?

MARGIE: Curly was about twenty-five. I don’t think Curly’s marriage broke up because of Jennie. I think something happened between him and his wife. It was probably his fault. I remember Curly used to take girls home in a taxi, and he’d tell the driver to stop off at his house first, as he needed to get money for the fare. He’d stop at a street around the corner from his house, and he’d go through the alley to his house, leaving the girl in the cab. He’d never come back, and she’d have to pay the fare. He was a devil—a real little devil.

JOAN: Did he work at all during this period?

MARGIE: Never—never. Never really worked a day in his life.

JOAN: I wonder why all Jennie’s sons idolized her and listened to her. Did they fear her?

MARGIE: No—no. She never touched them. She did give them everything they needed. There wasn’t much money to spread around, and she worked hard. She took old houses and barns and fixed them up, and my father [Irving] would sell them. This was before he went into the insurance business.

JOAN: Do you recall how Curly got that deep scar on his cheek?

MARGIE: Yes. He was in an automobile accident. He was in the Hupmobile, and a streetcar ran right into it. Curly was about twenty-one and he almost died.

JOAN: I got the feeling that Curly could have been a careless kid or had poor judgment.

MARGIE: I don’t know about that, but he did have idiosyncrasies. I know he never stayed in the house alone unless the lights were on. Every light had to be on when he was home.

JOAN: Was he a well man at that time?

MARGIE: His health seemed OK, but I got the feeling that he was a very unhappy man.

JOAN: Can you tell me more about Sol?

MARGIE: I remember a cute story that happened one Passover. Grandpa was sitting on the cushions at the seder and reading the service—and it usually took several hours—and all the boys were sitting around the table. They were starving. It was after 9:00 PM, and they still hadn’t served dinner. When Grandpa got up to wash his hands, Shemp jumped up and flipped the pages in Sol’s book. When he got back to the table, he went right on reading from the new spot that Shemp had turned to, never realizing what had happened. Shemp did this several times during the service, and, boy, did it go fast!

Portrait of a very handsome Curly. Evident on his cheek is the scar from his car accident (1933).

JOAN: Did Jennie ever put hundred-dollar bills under the kids’ plates?

MARGIE: I don’t know, but she did give me fifty cents once, and I thought I was rich. It only took a dime in those days to go to the movies. I remember one time—we had a Victrola—and Curly would put my feet on top of his shoes and dance around the room with me.

JOAN: I heard he was a wonderful dancer.

MARGIE: He was, he was—very light on his feet. And he had a nice voice, too.

JOAN: I have the feeling that Jennie took Curly to Europe to keep an eye on him, and not only to keep him out of show business, but to keep him away from his first wife.

MARGIE: Curly really liked that first wife. He was nuts about her. I think it really crushed him.

JOAN: I heard two stories about the first wife. One was that she was Gentile, the other that she was Jewish.

MARGIE: I’m sure she was Jewish.

JOAN: A lot of people said Curly was very vulgar.

MARGIE: He was vulgar, all right. He used a lot of four-letter words. My mother used to clap her hands over my ears when he would start to talk. But he was wonderful to me. One time he gave me five dollars, and it took me a whole year to spend it.

JOAN: Do you recall any of Curly’s likes or dislikes?

MARGIE: He liked to drink. He went out a lot. He’d come home and shower and get dressed, put on cologne and perfume. [Margie stops and lets out a cry.] Pauline—that’s her name, Pauline.

JOAN: The first wife? You’re sure?

MARGIE: Yes. Pauline.

JOAN: Do you think you could dredge up the last name?

MARGIE: No.

JOAN: Tell me more about Curly’s first wife.

MARGIE: I only saw her once, for a short time when Grandma lived on Eighty-Second Street. They [Jennie and Sol] had a beautiful house with a piano and everything. The first wife was there with Curly. He had married her and brought her over to introduce her to Grandma.

JOAN: Was this a surprise to Jennie?

MARGIE: Oh, of course it was. Now, I wonder—if she was Jewish.

JOAN: You seemed to like Jennie.

MARGIE: Yes. She was a wonderful woman; she was a crackerjack!

At the end of our conversation, Margie reminded me about her sister Ruth, who lived in Florida. Since she was several years older than Margie, I thought there might be a good chance she could recall something about Curly’s first wife; I was hoping to find out her last name. It took about six phone calls to reach Ruth. First I dialed three wrong numbers, after which I called her daughter Bonnie, a young woman in her thirties, who lives not far from me in Santa Monica. She sounded delightful and gave me her mother’s new phone number, and we made plans to get together.

Finally, at about six in the evening on Mother’s Day, I reached Ruth. I found out right off that her recall was not like her sister’s, but she did have several pertinent things to say.

Ruth Horwitz Leibowitz Kramer

May 12, 1985

Courtesy of the subject

JOAN: Margie told me a great deal about our grandmother, Jennie, whom I never really knew. What did you think of her?

RUTH: She was the sweetest—the sweetest. But she was a very tough businesswoman. Nobody got away with anything where Jennie was concerned. If she went to the butcher and he wanted Jennie for a customer, he had to give to her pet charities. With Jennie, you had to do her a favor in order to get a favor.

JOAN: I heard her children were very devoted to her.

RUTH: My father, Irving, was her favorite. Although sometimes she’d say one of the other sons was her favorite.

JOAN: What else do you remember about the Horwitz brothers?

RUTH: I recall several of the boys used to help her with the housework—like little girls. Curly never helped.

JOAN: Did he ever work?

RUTH: [Hearty laughter.] I don’t think so. I remember his eyes. They used to fascinate me. He had the bluest eyes. He was quite good-looking before he shaved his head.

JOAN: Do you recall his ever playing the piano?

RUTH: I only remember the spoons.

JOAN: You are about the fifth interviewee who has mentioned that. I don’t know if you know it, but he graduated from playing the spoons to ripping tablecloths.

RUTH: Really? He was very good-natured and very free with his money. When he came to visit, he brought my kids roller-skates. He used to hang around the poolrooms—not always with the nicest young men. And he gave Grandma lots and lots of trouble as a youngster.

JOAN: Trouble? What kind of trouble?

RUTH: He used to tell me that he didn’t graduate from school, Grandma did. That Grandma went to school more than he did.

Solomon Horwitz with his granddaughter Ruth (1922).

JOAN: Poor Jennie. I heard that Shemp played a great deal of hooky, too. Oh, yes, someone also described Curly as a loner. When I say loner, I mean not having any close friends but hating to be alone. Is that true?

RUTH: Yes. He had an obsession about being alone. A phobia—almost a fear.

When Curly returned to New York from his Pittsburgh visit with Bernice and her family, he was surprised to find Jennie nervous and uptight. The tentacles of the Great Depression were closing in. Unemployment was rampant, land was just not selling, and burdened with dozens of mortgages on her properties, she was about to have the bottom fall out of her real estate enterprises.

Although Jennie’s world was about to tumble, the Great Depression of the ’30 would be a golden era for Curly. He would continue with Orville Knapp for several more years of waving his baton and losing his pants—and then lady luck would step in and change his life forever.

* Years after the first edition of this biography was published, the marriage license finally surfaced. For the story of its discovery and updated details on Curly’s first marriage and the timeline of his early adulthood, see the afterword, page 181.