Where his life was concerned, Curly was still not in the driver’s seat. Jennie continued to rule him with her iron hand, and much of Curly’s days were spent behind the wheel of the Horwitz Hupmobile, chauffeuring his busy mother all over town. One of the highlights of 1930 was a visit by Sol’s sister Esther and her daughter, Emily, who had come in from St. Paul. Curly was elected to squire them around. This was the same Esther who was the household servant Jennie had imported from Lithuania in the Bath Beach days. Her daughter, Emily, was a beautiful young girl, and Curly, for the first time, looked forward with pleasure to driving someone about the city. His pleasure was doubled when his mother explained that she had tickets for the theater and they would all be going to Manhattan to see Moe and Shemp in their latest vaudeville extravaganza.

Jennie was in a generous mood and, possibly feeling remorse over her past treatment of Esther, seemed honestly concerned with showing her sister-in-law and her niece a good time. She had made plans to take them to dinner in a fine New York restaurant, and Moe had taken care of getting them all house seats.

Jennie’s royal treatment of her relatives began with an incredible drive down the Great White Way, along its fairyland of sparkling lights. Emily and Esther were impressed, and the sights and sounds and glitter of Broadway were things that Curly never tired of. Being a part of it was his constant dream, and his imagination always went wild when he visited the area. Then, as he rounded a corner, there was the epitome of theaters—the Palace—and up on the brightly lit marquee, headlining the bill, for all to see, was his brothers’ star billing: TED HEALY AND HIS RACKETEERS.

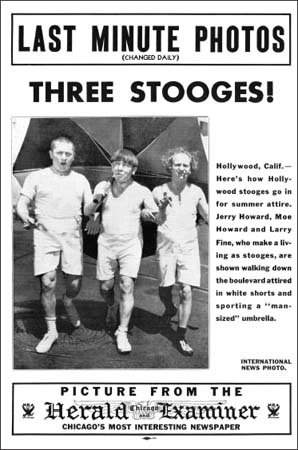

Inside the legendary theater, Curly watched bug-eyed from fifth row center as Ted Healy, who always came onstage with a battered hat—his trademark—banged and pounded his Racketeers. Healy’s stooges at the time consisted of four members: There were Curly’s brothers, Moe and Shemp Howard, and their partner, Larry Fine, who had been with the team since 1928, when he was discovered in a Chicago club doing a Russian dance in high hat and tails while playing the violin. The fourth team member, newcomer xylophonist Fred Sanborn, was with the team for a very short time. The Racketeers were a motley crew, but they performed their zany Stooge antics with precision timing, taking the brunt of Healy’s roughhouse humor and physical abuse. It was a wild, slapstick performance marked with crudity, and the audience ate it up.

My cousin Emily Trager, who was with the family at the Palace that night, told me, “The audience laughed so hard that in order to keep their patrons from choking, the theater owners had ushers running up and down the aisles serving water. Curly laughed so hard that he had two full glasses, but uptight Jennie didn’t require a single drop. She sat stone-faced through the entire performance and never even cracked a smile.”

Curly that evening was like a man gone mad, dying to get up on that stage, to be the center of attention. His mind raced with both jealousy and frustration at being on the edge of the spotlight and not illuminated by it as Moe and Shemp were. At home, later that night, he pleaded with Jennie to allow him to go into show business full-time.

Jennie was an expert at camouflaging her iron hand with a velvet glove. “Who would take me to the Home for the Aged? Who would take poor Sol to shul?” she pleaded. Jennie claimed that she desperately needed him, and Curly, no match for this clever little woman of steel, gave in. But deep down he had made up his mind. There would be no college or trade school for him. He would bide his time, watch his brothers’ act, and study their style until he had it down pat. When the time was right, he’d be waiting in the wings, Jennie or no Jennie.

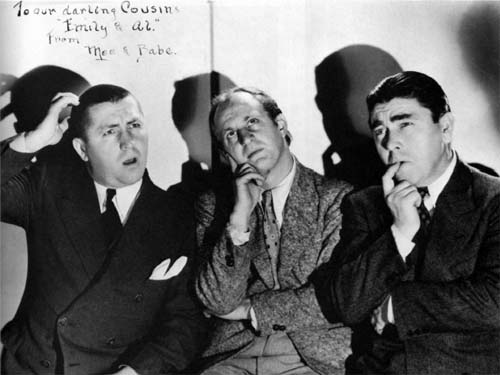

Ted Healy and His Racketeers, circa 1930. Larry, Moe, Shemp, and Fred Sanborn in a scene from Fox’s film Soup to Nuts (1930).

Night after night he would drive to the theater and sit there absorbing every nuance until, suddenly, his watching and studying of Healy and his Stooges came to an abrupt halt. A talent scout from Fox Studios saw the act at the Palace and hired Ted and his Racketeers for Fox’s new feature film Soup to Nuts, written by the famous cartoonist Rube Goldberg. Two of the Horwitz boys had finally made it to the “big time” and would soon be Hollywood bound.

The following week, Curly drove Moe, Shemp, and their families to Grand Central Station, where he witnessed their elation as they waved from the rear platform and the train chugged out of the station, taking them all to Hollywood. When he returned home to Brooklyn, he was in a state of depression, wondering when it would be his turn and what it must feel like to be a movie star.

Curly, his show business dreams and ambitions in a holding pattern, waited patiently for his brothers to return. It was late in 1930 when he received his first letter from Moe, explaining the details of what had taken place in Hollywood during the past several months. Moe’s letter related how the Stooges’ stint in Soup to Nuts was well received by both the press and the studio heads and Healy had come off second-best. Only Moe, Larry, and Shemp were offered a contract with Fox. Then, several days later, the contract was canceled. It didn’t take Moe long to realize that they had been betrayed by Healy, who had gone to his old pal Winnie Sheehan, the production head of Fox, and coerced him into canceling the Stooges’ contract. It was both fear of losing his act and jealousy that had driven Healy to cut the Stooges’ throats. Because of this incident, Larry, Moe, and Shemp refused to continue their association with Ted.

Ted Healy and His Three Southern Gentlemen, circa 1930.

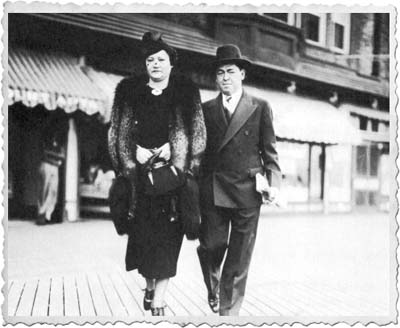

Papa Moe, Momma Helen, and the author, on tour in Seattle, Washington (1930).

As he read the rest of Moe’s letter, Curly found it hard to believe that Larry and his brothers would be working without Healy and that they would open at the Paramount Theater in Los Angeles. In closing, Moe wrote that they would take their new act across the country, using most of the material from their old routines with Healy, but were changing their names to the Three Lost Souls.

The weeks dragged into months, and Curly was learning patience with a capital P. He would need it. Moe and Shemp would not return to New York City until late in 1931. Their personal appearances would keep them busy for months, and weeks would be spent in a California courtroom, when Ted Healy sued them for using his material in their new act.

More letters to Curly followed, and in September Moe wrote to him that they had won their lawsuit with Healy. In closing, Moe penned, “Healy is desperate to get us back. His replacement stooges were a terrible disappointment to him. He has promised to stop drinking and I hope we’re not making a mistake but we’ve decided to go back to him. We’ll be arriving in New York next month for rehearsals for the new Shubert musical, The Passing Show of 1932. Your loving brother, Moe.”

Shemp portrait (1930).

Weeks later, Curly received a call from Shemp, who cried on his shoulder, telling him that he was fed up with Healy. They had rehearsed The Passing Show for four weeks, and then Ted and Shubert had an argument over salary. When Ted found a loophole in his contract, he decided to leave Shubert to take a more lucrative offer from the Balaban & Katz circuit.

Shemp was sick of Healy’s deviousness, his alcoholism, and his cruel practical jokes. He confided in Curly, “To tell you the truth, I’m afraid of him, and I’ve decided to let Healy leave with Moe and Larry. I’m going to stay in the Shubert show.”

Then Shemp dropped a bomb that exploded happily in Curly’s ears: “It’s possible Moe and Larry will be looking for a replacement for me. They need a third stooge!”

Ted, Shemp, Moe, and Larry at the stage door, circa 1931.

Curly’s older brother Irving and his wife, Nettie, visiting the Stooges in Atlantic City (1931).

A third stooge! Curly went mad with excitement. Was this his long-awaited chance to become a star? At that glorious moment, if he knew how to do it, he might have woo-wooed and n’yuk-n’yuked at the top of his lungs. Instead, he started to laugh hysterically.

When Curly regained his composure, he called Moe, who corroborated Shemp’s story, adding that Healy was furious—out to kill—and had accused Shemp of trying to destroy the act. Moe then said, “Healy asked me who was going to replace Shemp. I told him that I’d call my brother Jerome. Babe, you have an appointment with Ted Healy tomorrow at two o’clock.”

Curly was beside himself with joy. He wanted to shout the news throughout the house, but he feared that his mother would never understand. Instead, he went straight to the Triangle Ballroom, downed a dozen beers, and danced until dawn.

The next morning, when he awoke, he had a bad case of the jitters. Would Healy accept him? He had so little stage experience. The only professional work he’d done was dropping his pants for Orville Knapp. But he had studied Shemp and Moe’s act for the last few months and had followed them around for years, and he knew their routines backward and forward. The odds, he thought, were in his favor, and he was determined to prove to Healy that he would make the world’s greatest stooge.

The meeting with Healy started out disastrously. Moe was rooting for him so hard that his nervousness was engraved on his face and infected Curly. When Healy asked Curly what he could do, Curly croaked out, “I don’t know.” And then Healy retorted with, “Well, I know what you can do. You can shave your head.”

Curly chuckled at what he was certain was one of Healy’s sick jokes. Then Healy turned to Moe and Larry Fine and said, “Look, boys, he looks too normal with his wavy hair and waxed mustache. Moe, you have this spittoon haircut, and Larry, you look like a scared porcupine.” Then he turned to Curly and said, “You just don’t fit in.”

The meeting ended, and Curly went home feeling sad and beaten. Alone in his room, he started to think maybe Healy wasn’t joking. Maybe he should shave his head. The thought repelled him. The only things that made his life worth living were music and girls. How could he go to the Triangle with a shaved head? And what would his friends think? God! What would Jennie think? But he wanted this job like life itself. This was the point of no return. The hell with everyone.

Curly woke up the next morning feeling hungover, although he hadn’t had a thing to drink. But like a drunk in a stupor, he dragged himself to the barber, cap in hand, knowing that he wouldn’t be able to face the world again without something covering his head.

In the barbershop, Curly blurted out instructions for his haircut, shouting, “Shave my head—shave it right down to the bone.” Having meticulously trimmed Curly’s hair for several years, his barber wouldn’t have been any more surprised if he had said, “Take your razor and slit my throat.”

It took some convincing to assure the barber that this was no joke, and finally the clippers whirred ominously as they mowed their way through his wavy locks. For minutes that seemed like hours, Curly felt as though he were undergoing major surgery. Then he took one glance at the bald-headed stranger in the mirror staring back at him, and one glance was enough. He quickly paid his tab, grabbed his cap, jammed it down over his head, and dashed out.

The next meeting with Healy was markedly different. Curly had everything planned, right down to his grand entrance. An impressed Healy watched as Curly ambled in, skipping along, looking like a fat fairy. When he pulled off his cap, it took only seconds for a grinning Healy to say, “You’re in, Jerry.” With tears of joy rolling down his cheeks, my uncle blurted out, “If you want me, call me Curly.”

He’d done it. He was finally in, and there was no turning back. From here on, Jerome/Jerry/ Babe Horwitz would forever be just plain Curly to millions of theatergoers and an army of loyal fans, most of whom were yet unborn.

That same week in 1933, the traditional Friday-night dinner at Jennie’s was a traumatic event for our new Stooge. Curly sat down at his mother’s table with his little cap pulled down hard over his head, wishing that Shemp and Moe were there, because they knew how to handle Jennie better than he did. Sol was already seated, his yarmulke on his head, meticulously slicing the challah on the plate in front of him. Jennie entered, scowling as she stared at Curly’s cap pulled down rakishly over his ears. He knew that he would have to remove it and replace it with his traditional little blue velvet yarmulke, which would expose his Spartan skull. What would his mother’s reaction be when she glimpsed his shiny bald head? The thought panicked him. This was showdown time—time to be his own man. He whipped off his cap and Jennie screamed. She literally jumped out of her chair and shrieked in horror at the top of her lungs. Curly felt as though he were drowning. He was speechless—in a state of shock equal to, if not surpassing, Jennie’s. Finally, when the words did come, they were totally scrambled. “Mom,” he stuttered, “I’m a stooge—I’m actually a stooge. Don’t worry. It’ll grow, and you’ll grow to love it.”

With that, Jennie started to cry. “I knew it! I knew that this show business thing was a curse.”

Curly stood up and moved closer to her, searching for a way to soothe her anguish. He felt terrible. Jennie had done so much for him through the years, given him everything he ever wanted. He couldn’t hold her close, because there were never hugs and kisses in the Horwitz family, but he always knew the love was there. His father sat like a stone, staring at them, never saying a word but with a hint of a grin on his face. Then Sol, who rarely ever spoke, said softly, “I envy you, my son. You have something now that will give your life meaning.” Both Jennie and Curly stared at him, and words failed them. That was the most that either had ever heard Sol say at any one time. It broke the tension of the moment and made Curly feel better. He grabbed his blue velvet yarmulke and, with a flourish, slapped it over his shaved skull, and the three finished their dinners in silence.

The biggest hurdle in Curly’s young life was over. He had finally severed the cord. Curly, who had changed his last name to Howard, was in show business at last, and his domineering mother would have to learn to accept it.

And then came the usual doubts, heartaches, and problems that plague most neophytes in any profession. During the first few weeks of his new career. Curly noticed that Healy was reticent about letting him use any of Shemp’s material, which he had studied for months and knew by heart. Healy was concerned about Curly’s inexperience, and in the beginning all he allowed him to do was run across the stage in a tight-fitting bathing suit, carrying a little pail of water. It was a hysterically funny sight—this fat, bald Humpty Dumpty of a man skittering about half-naked with his little dripping pail—but Curly was still frustrated. He knew he could do more and could get even bigger laughs from the audience.

Each night the laughter increased as Curly, gaining assurance with every laugh, milked his routine for all it was worth. With each succeeding performance, he sneaked in a line or two of Shemp’s routines and, as he anticipated, the audience howled even louder. Healy was an astute showman and, knowing a good thing when he saw it, eventually gave his new Stooge free rein. Curly, through his own ingenuity, had worked his way into the act and had become a full-fledged comedian.

By the time Healy and His Stooges played the Club New Yorker in Hollywood’s Christie Hotel, Curly had taken over Shemp’s role completely, added his own incredible touches, and become the best stooge Healy ever had. It was there, in this basement nightclub, that an MGM scout watched the performance of Ted Healy and His Stooges for the first time and was impressed. Then, as their act ended and the audience applauded, the entire room shook. But it wasn’t only from the applause; chandeliers swayed and the room rocked as plaster and dust plummeted from the ceiling. This was the 1933 Long Beach earthquake, which sent its shock waves throughout Los Angeles. It was an unforgettable night for everyone present at the Club New Yorker, and especially for the Stooges, who were signed up on the spot to a one-year contract by the MGM scout.

Ted Healy and His Stooges at the Club New Yorker in Hollywood’s Christie Hotel. It was during this engagement that an earthquake wrecked the nightclub (1933).

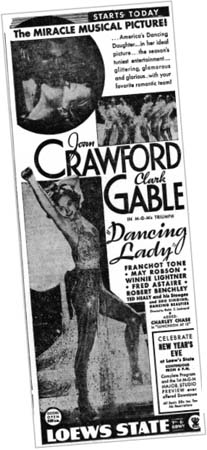

Curly, Moe, and Larry harmonize with Ted Healy in Dancing Lady (1933).

For Curly, 1933 was a dream come true. For the time being he would have no regrets about that traumatic day at his barber when he shaved his head. He was among the stars: Garbo, Gable, Crawford—the cream of the movie industry. Curly was a star now, too, and with it came adulation, girls, applause. This was Hollywood in its heyday, and Curly was finally a part of it.

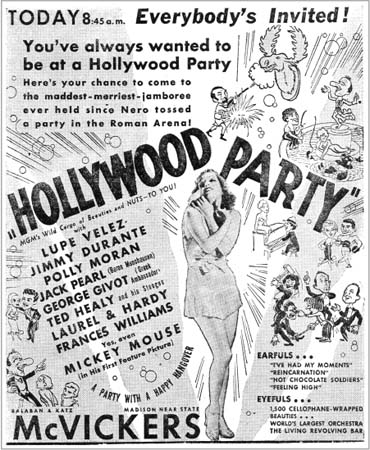

The Stooges’ first feature appearance was in MGM’s Turn Back the Clock, with Lee Tracy and Mae Clarke. This was followed by Meet the Baron, with Jimmy Durante, and then Dancing Lady, Fugitive Lovers, and Hollywood Party. Healy and His Stooges were on a roll, also starring in five MGM musical-comedy shorts, the first of which, Nertsery Rhymes, was released in two-strip experimental color.

Curly was on cloud nine when he read his reviews, and always the thoughtful son, he wanted to share his joy with his mother. He sent her a clipping of a wonderful review of Nertsery Rhymes and informed her of the date it would be playing in the Horwitzes’ neighborhood theater in Brooklyn.

On a summer’s day in 1933, Jennie, who had often seen Moe and Shemp slapping and poking each other on the live vaudeville stage and always shivered at the sight, had never seen any of her sons on the silver screen, so she marked her calendar and decided to attend the theater at an afternoon matinee.

This staid, stern Victorian woman sat in the front row and struggled to ignore the screaming kids who raced up and down the aisles tossing popcorn or anything they could get their hands on at each other and at the screen as they waited for the show to start.

Suddenly, the house lights dimmed and the screaming and whistling of the kids accelerated as the MGM lion roared and the title flashed on: TED HEALY AND His STOOGES IN NERTSERY RHYMES.

Onto the screen, larger than life, came Ted, Larry, and then finally Moe and Curly. Jennie stared ahead, her face frozen into impassivity as hammers and mallets were swung at her boys, with most of the blows landing on the head of her baby, Curly. The exaggerated sound effects and the ear-shattering clangs and boings were frighteningly realistic to her.

Ted Healy and His Stooges, with Bonnie Bonnell, in MGM’s Nertsery Rhymes (1933).

As this incredible on-screen mayhem increased in intensity, Jennie became more and more agitated and, unable to hold back her emotions, began to mutter under her breath in a mixture of English and Yiddish: “Vey—you crazy idiots! To Hollywood you had to go to kill each other.” Then she totally lost control and, recalling her sons’ vaudeville act—which she hated—screamed, “Not enough you should poke fingers in the eyes, now you gotta use clubs and hammers.” Ignoring the kids in the nearby seats who stared at her, she continued shouting at the screen: “Moe, you no-goodnik! That’s your baby brother Babe you’re smashing! For this I slaved all my life—so my sons should be movie stars. Feh!”

Unable to contain herself and totally frustrated, she bolted from her seat and charged up to the stage, waving her umbrella menacingly at the screen, and in a hysterical voice screamed, “A pox on you, Ted Healy!”

Moments later, poor, old-world Jennie was still muttering under her breath in her broken English as the confused usher took her gently by the arm and escorted her out of the theater.

Despite Curly’s love for this magical world of showbiz, his shaved head would always diminish his confidence in his appearance. He constantly wore a hat and, to give himself a bit of needed courage, would always belt down a few quick ones before approaching the fairer sex. During vaudeville tours, after he would finish taking his nocturnal beatings onstage, the local nightspots were his home. He still loved music, and a drumbeat or a bouncy number would always start his feet to tapping. Many evenings at a nightclub, when he was feeling no pain, he would take the edge of a tablecloth between his thumbs and forefingers and rip the fabric to the tempo of the music. After the tablecloth was in shreds, he’d take two spoons and click the backs together until the silver plating was covered with dents. Curly was able to make those two spoons sound like a pair of castanets, and there were often times when he would actually jump up on the bandstand, grab the bass fiddle out of the hands of a shocked musician, and plunk away as well as any professional. Throughout his life, Curly was always a night owl, and much of his salary would be squandered in order to pay for shredded tablecloths, pockmarked silverware, and broken bass strings.

Paying off nightclub owners and struggling to overcome the trauma of his shaven head were minor problems in Curly’s life in these heady days. Greater concern centered on his parents. The country was in the grips of a major depression, and Jennie—mortgaged to the hilt with her many real estate holdings—was on the verge of bankruptcy.

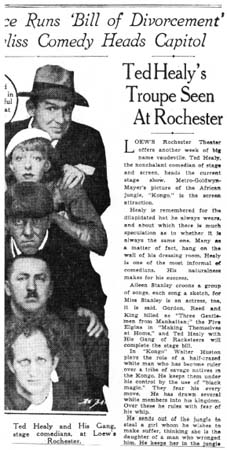

News clipping of Ted Healy and His Gang (1932). Curly, with shaven head, still sports his mustache.

Curly in Hollywood—with Moe, Larry, and Ted Healy onstage at MGM (1933).

News clipping of MGM’s Dancing Lady with Crawford and Gable … and Healy and His Stooges (1933)

Hollywood Party (MGM) news clipping. Ted Healy and His Stooges get billing above Mickey Mouse (1933).

Curly with Edna May Oliver in a publicity still from MGM’s Meet the Baron (1933).

Curly in a rare solo performance in MGM’s Roast-Beef and Movies, with George Givot and Joe Callahan (1933).

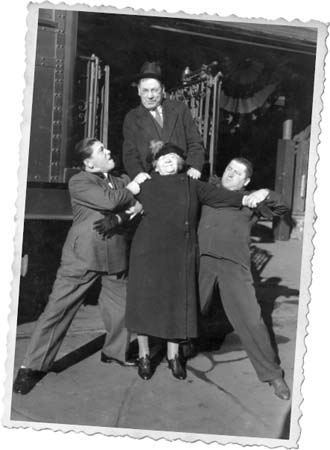

Moe and Curly rough up Momma Jennie and Poppa Sol as they arrive in California for the first time (1933).

Curly, center, with his favorite people—Mabel, Larry, Moe, and Helen (1933).

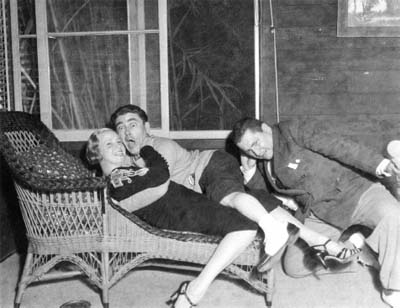

Helen, Moe, and Curly clowning at a friend’s beach house (1933).

Publicity shot of the Stooges, circa 1933.

MGM back lot (1934).

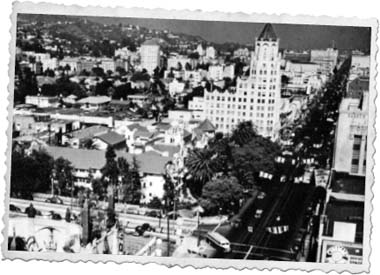

A dream come true: Curly’s new home, Hollywood, 1934. Bison Archives

Curly and the boys attempt to hammer some sense into Bonnie and Ted.

Added to his concern for Jennie was his concern for his favorite brother, Moe, who was showing signs of discontent, brought about by Healy’s unfair treatment of his Stooges. Healy had reneged on his promises to reform and was still drinking heavily and playing outrageous practical jokes. That was bad enough, but Healy, although he was earning several thousand dollars a week as payment for the act, including his three Stooges, was still paying them their original salary of only one hundred dollars a week.

Despite the fact that Healy was a talented performer on his own, every review singled out the Stooges as having made the act something special. When Moe digested the full meaning of the positive press that he and his partners were getting in both California and New York, he finally got up enough courage to sever the cord with Ted. He confronted Healy at MGM and amicably put an end to their long relationship. It was 1934, and the Stooges, for better or worse, were ready to strike out on their own.

The details of Moe, Curly, and Larry’s parting of the ways with Ted Healy and then signing their contract with Columbia in 1934 had all the makings of a movie script. After the final meeting with Healy, Moe walked out of one MGM gate and signed a contract for the Three Stooges with Columbia Pictures, totally unaware that Larry had left from another MGM gate and signed another contract for the Three Stooges with Universal Studios. The two contracts went to the lawyers of Columbia and Universal and finally to a judge. In the end, the evidence indicated that Moe’s Columbia contract was signed several hours before Larry put his signature to Universal’s. Columbia got the Stooges, and Larry would never again, for the next half century, ever conduct any of the Three Stooges’ business.

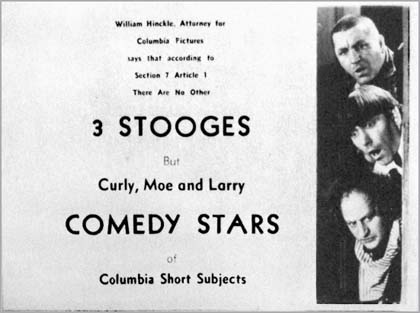

Columbia legal department advertisement to warn off Stooge infringers (1936).

Moe had taken over completely as manager of the Stooges’ act, and Curly, forever busy buying shiny new cars and driving down Hollywood Boulevard yelling “Hiya, toots!” at every pair of pretty legs, was satisfied to let him handle all business matters for the act as well as personal matters for himself.

Curly had become a major star in the Short Subjects Department at Columbia Studio and made his first film, Woman Haters, a musical comedy all in rhyme. Although this was Curly’s first Columbia short, it was not a Three Stooges comedy as we know them today. The boys were not yet known as the Three Stooges or working together as Larry, Moe, and Curly. In this film, Curly and Moe appear as supporting players, with Larry in the role of the leading man. It wasn’t until June 1, 1934, that the three officially took on the name “the Three Stooges.”

One of Curly’s favorite hangouts, the Cafe Trocadero on the fabulous Sunset Strip (1934). Bison Archives

The Columbia Ranch western street in 1934, where most of the Curly shorts were filmed. Bison Archives

Moe clowns around trimming Curly’s hairless head in a dressing room at Columbia Studio. Note Curly’s faithful hat on his shelf (1934).

A publicity still sent by Curly and Moe to their cousin Emily and her husband, Al (1934).

Clarence Bull / MGM

After completing Woman Haters, Curly and his partners waited nervously for word from Columbia’s executive office as to whether they would be hired to make another film. Then Moe, impatient to go back to work, came up with a wacky story idea for a short titled Punch Drunks and submitted it to the Columbia executives. The studio was so impressed with his original story that they signed the trio to a seven-year contract with yearly options. The Stooges would make eight shorts each year for Columbia with a twelve-week layoff period to perform in any entertainment category except making films for other studios. Curly was thrilled when his $333-a-week paycheck, which was a great deal of money in the ’30s, was suddenly raised to a whopping four-figure salary. He felt like a millionaire and spent like crazy, and Moe had his hands full struggling to hold him down and make him save for the proverbial rainy day. But it was a losing battle. Curly was in the big time and living big. Wine, women, song, cars, dogs, and houses were there for the taking, and Curly managed to spend his entire weekly check before it was even handed to him.

In the ensuing years, Curly would perform in ninety-seven Three Stooges comedies for Columbia. Most of the films were quite violent, and the bruises that Curly endured were many. It’s amazing he survived the battering, in which his bald dome took the brunt of the punishment—be it squashed in a printing press, slammed into a doorjamb, or sliced by a scimitar. If the Guinness Book of Records had a category for bops, bangs, and bruises received in the line of work, Curly would certainly hold the world record.

In one short, he was supposed to fall down an elevator shaft. A hole deep enough for Curly to be concealed from the camera after he landed was constructed in the stage floor. The special-effects man covered the bottom with a protective mattress to soften the impact but neglected to cover the sides of the opening, which were constructed with exposed two-by-fours. When Curly was pushed into the elevator shaft, his head hit the wooden framework, cutting his scalp wide open. The studio doctor rushed to the set, where he washed Curly’s wound and sealed it with collodion. It was an example of the old saying “The show must go on.” Minutes later, the head of the makeup department was rushed to the set to cover the wound with makeup, and a wobbly-legged Curly continued with his scene as if nothing had happened. Life was rough for the superstooge in front of the cameras and equally rough during the eleven years he performed onstage.

In addition to the multitude of bangs and bops that Curly received on hundreds of theater stages across America, much of his trouble during vaudeville tours came from drunks and children. They had often seen Curly take horrendous screen punishment and, like Jennie, believed what they saw and were convinced that Curly was made of steel.

Drunks would often stagger up to him and shout “Hiya, Curly!” and then smack him hard on his famous indestructible bald head. Children, at times, could be even more of a problem, because an impressionable child who had seen him clobbered on the screen wasn’t mature enough to realize that lethal props such as hammers, crowbars, and sledges were made of foam rubber. Once in Atlantic City, when Curly was on the Boardwalk, lost in his thoughts, staring at the ocean, an eight-year-old boy carrying a small cane recognized him. “Look, Ma,” he cried.

Larry and Moe showing off their rings to a ring-less Curly. Publicity shot (1935).

“‘There’s one of the Three Stooges.” Running up behind Curly, he took a tremendous swing and conked him over the head with his cane. Whirling around, Curly faced the young fan with glazed eyes, wobbly legs, and clenched fists. Then he noticed the boy’s heavyset mother, beaming, grinning at her son as if proud that her kid had bopped the indestructible Stooge. Curly was momentarily taken aback. Regaining his composure, he smiled, took a cute Curly-style bow, and then grasped the railing next to him for support as his legs buckled.

The Stooges are billed above the marquee at the RKO Palace Theater—even above Bette Davis (1936). Notice the old spelling of Curly (Curley).

Larry and Curly charm Mildred Harris with their music in Movie Maniacs (1936).

This Boardwalk incident took place in 1935, the same year that Curly’s parents went bust. The real estate bubble had burst, and Curly wrote Jennie and Sol and begged them to move to California. To Jennie, only Brooklyn was America and God’s country, and despite her monumental financial setback, she refused to leave. It took a great deal of Curly and Moe’s convincing to get her to relent and emigrate from her cherished Bensonhurst. In 1937 she finally agreed to make the move west, and her two famous sons pooled their resources and set their parents up in a lovely home on the edge of Beverly Hills.

In her sixties and suffering from high blood pressure, Jennie was not able to fully enjoy her new California home. I vividly recall my visits to my grandparents’ as a ten-year-old. The house was always dark, with all the windows closed and the shades drawn. The air was extremely close inside and often smelled of sickness.

Despite the fact that Jennie was seriously ill, my grandfather, Sol, was still able to get around and would take a bus to downtown Los Angeles and visit with some of his Brooklyn cronies who had also moved to California. On one of his visits he was introduced to a very pretty dark-haired young Jewish girl, Elaine Ackerman. Impressed with her, he decided to play cupid for his son Curly. However, Sol’s arrow missed its mark. Elaine was not interested in a blind date and refused to meet his son. But fate moves in strange ways. By an unusual coincidence (described later in an interview with Elaine), she wound up on a date with Curly shortly thereafter, and it was love at first sight—sort of.

Elaine soon became Curly’s second wife in a simple ceremony in my grandparents’ temple in Hollywood. Shemp, Moe, Larry, and their families were there, and Jennie left her sickbed to join the festivities.

Curly beams as Momma Jennie and bride Elaine greet each other at his wedding reception (1937).

Curly and Elaine showing off her engagement ring to a smiling Jennie and blasé Sol (1937).

Curly and Elaine at their engagement party (1937).

Curly waits impatiently for the tardy rabbi to show up and tie the knot (1937).

The author on the receiving line at her uncle Curly’s and aunt Elaine’s wedding (1937).

Curly, Shemp, and Moe rough up their father on Curly’s wedding day (1937).

Shemp’s wife, Babe, on the receiving line at Curly’s wedding to Elaine (1937).

Elaine poses with her new in-laws, Sol and Jennie, on her wedding day (1937).

Elaine poses in front of her Reno, Nevada, cabin on her honeymoon in 1937.

The Curly residence, one of many, on Highland Avenue in Hollywood, where he lived with Elaine.

The Stooges clown around with Curly’s new bride, Elaine, in Curly’s new home.

As for Elaine’s short-lived marriage to Curly, my cousin Emily Trager felt that Elaine’s parents and Jennie had much to do with their divorce. Another cause was the fact that Curly was rarely at home and Elaine was continually left alone. Emily also felt that Curly was sorry that he had divorced Elaine. Elaine, on the other hand, had quite different thoughts on the subject, and I was determined to learn more about her relationship with my uncle Curly and find out what finally caused them to split up.

In spite of past family friction, I have kept in touch with my aunt Elaine through the years and was delighted when she agreed to be interviewed on this touchy subject.

Elaine Ackerman Howard Diamond was born August 12, 1914, in Far Rockaway, New York. Her parents, Emma and Isadore Ackerman, moved to California sometime in the ’20s, and her father opened a jewelry store. Elaine’s education after high school included two years at UCLA. In 1937 she married Jerome “Curly” Howard, had a daughter, Marilyn, with him in 1938, and received her final divorce decree in 1941. Elaine married Moe Diamond in 1943, and in 1944 the two had a son, Michael. Elaine and Moe resided in the San Fernando Valley.

Elaine Ackerman Diamond

March 25, 1985

Courtesy of the subject

JOAN: I was too young to really know Curly’s mother—my grandmother. What was Jennie like?

ELAINE: This was a very cold woman. I never really got to know her well either. We met for the first time about six months before Curly and I were married. Then we left on our honeymoon and, after that, for a personal appearance tour.

JOAN: What was Curly’s father like?

ELAINE: Well, I liked him. He lived with me from the time Jennie died. Why they picked me, I don’t know. We lived at the time on Highland in a rented house. It was very close to Moe’s house. I guess it was because I had more room than your mother. Marilyn was a baby when Sol moved in with us, and he was shocked that I gave her bacon. My pediatrician had recommended it. Sol was very orthodox and very kosher, and he had a fit.

JOAN: It’s funny that you should speak of my grandparents and bacon, because that is one of the only stories that I recall about my grandmother. I was about eight, and I was as anemic as any child can be—skinny too—and the doctor had me on a diet to get fat, and one of the foods was bacon. I recall the story to this day. I’d visit my grandmother and she’d always quiz me about what I had eaten that day, and when I answered, “A bacon sandwich—and mother made me put butter on it,” I thought this very kosher lady would faint. She glared at my mother, and I knew that I had said something very wrong.

ELAINE: But I honestly tried to adhere to Sol’s dietary rules. At one time—I’ll never forget this as long as I live—we had to soak our dishes in the bathtub to make them kosher for Passover. And no one was able to use the tub for over a week.

JOAN: Did they put anything in the water?

ELAINE: I think … salt. I’m not sure.

JOAN: Did Sol read a lot?

ELAINE: I don’t recall, but there was another thing that I resented about him—not necessarily about him but all people that believe in orthodoxy. I am not a religious person. I went to Sunday school. My mother wanted us to learn the history of the Jewish people, and after that we were on our own. We had very little religion in our home. I remember … Sol would get up about five in the morning and go to shul, and then again at five in the afternoon. In between he’d rant and rave that everybody—they should drop dead, they should burn in hell, things like that.

JOAN: People that he knew?

ELAINE: No—the help—because they used too much water. He would watch them like a hawk.

JOAN: It’s funny that you mention this, because in one of my interviews with my father’s niece, Bernice Herzog, when I mentioned that one of Sol’s sisters worked in Jennie’s house, she laughed hysterically and said, “That girl must have really suffered. You heard about the help that worked in the Horwitzes’ house? Jennie and Sol screamed at them constantly.” I wonder if Sol could have been getting senile.

ELAINE: I don’t know. In later years, it bothered me to think that anybody so religious had to spend his days cursing.

JOAN: He was almost seventy then.

ELAINE: I’m not senile, and I’m seventy.

JOAN: Was Curly creative in his offscreen life?

ELAINE: Did you ever know that they told me that Curly was a child prodigy at the piano?

JOAN: I knew that he had a wonderful voice. It’s possible that he played the piano. My cousin told me he worked as a song plugger, and usually song pluggers played the piano as they sang.

ELAINE: I remember that when Marilyn was growing up—after I was divorced—she wanted to take piano lessons, and I said to [my husband], “We’ve got to get a piano for her; she may be like her father.” I don’t know who told me about Curly’s talent—his mother or Shemp’s wife, Babe. Marilyn had no talent at playing piano, but her son, Darren, seems to have picked up the musical gift, because he plays the piano extremely well. He graduated from San Francisco State, Phi Beta Kappa, cum laude in Drama and Musical Arts.

JOAN: What kind of career did you have?

ELAINE: I started in my early years at the May Company as a saleswoman, and then I went to college, and my first job was secretary to the comedian Joe Penner. After that, I got a job as a secretary to a well-known business manager for movie people. And then I started working at the place where I met Curly.

JOAN: How did you meet Curly?

ELAINE: That’s a very funny story. At that time, I worked for a wholesale furrier on Los Angeles Street, downtown. I was a model and also worked in the office. I remember … everybody wanted to fix me up with their friends. One day your grandfather, Sol Horwitz, came in, and when he left, my boss said to me, “This man has a son who is one of the Three Stooges.” At that time, I’d never heard of the Stooges. I was not into comedy or anything like that. My boss said they were very well-known comedians and that Mr. Horwitz would like me to meet his son. I told him I was really not interested. The next day, as I was ready to leave for lunch, in comes Curly Howard. I was introduced to him, and then I left for lunch. When I came back, he was still there, and he didn’t know what to say. He was rather shy with me. He finally said, “Did you have a good lunch?” And I said, “Yes, thank you.” And I went back about my business. Well, the next thing that happened—this is really a coincidence—that evening, a doctor that I had dated before called; he was staying at the Ambassador Hotel. He had no car, and the first time we went out, my mother let us take her car. This was the same night as the day I had met Curly—and I get a call from this doctor, and he asks me out for dinner. This time I suggested we take a cab. I didn’t want to ask my mother for the car again. He told me he didn’t need a car, as he had just made friends with someone at the bar and we were going to double date with him, and he had a car. I don’t know what made me ask, but I said, “What’s his name?” Then he said, “Well, he’s one of the Three Stooges. His name is Curly Howard.” I said, “Well, you tell Mr. Howard that I’m the girl that works for Morty Mandel, and I met him today.” Well, that was like an omen to Curly. He got on the phone and told me that they would pick me up. And that was the beginning of the romance.

JOAN: What an unusual story. I guess truth is stranger than fiction.

ELAINE: He swept me off my feet. He seemed to think it was meant to be. To meet twice in one day—and such different circumstances.

JOAN: And to have his father play cupid!

ELAINE: After that, I honestly didn’t know what hit me.

JOAN: How old were you?

ELAINE: I wasn’t that young. I was about twenty-two. We didn’t go together long. We got married the next year. [Pause.] I just thought of another very interesting story, one that occurred when we were engaged. Curly gave me a lovely ring that he got from my father, who was in the jewelry business. It was a beautiful diamond. This was about a week before we were to be married. He explained that he had to supply the liquor for the wedding. He told me he was going to pick me up and go to the Ambassador to see about the liquor, and I told him that I had a friend who lived nearby and that I would visit her and then come back to pick him up. I went to my friend’s house but she wasn’t in. And right in the next block was [Dr. Mueller], our family doctor. While I was engaged, I used to take Curly’s mother there. As I drove up the street, I realized that this was the street where the doctor’s office was. I said to myself—like I had ESP—”If I see Curly coming out of that doctor’s office, I’ll know that there’s something terribly wrong.” And at that very moment, I see Curly coming out. Well, I was just in shock. When he came over to the car I threw the ring at him and said the wedding was off, that I couldn’t trust anybody that lies. How could he tell me he was going to the Ambassador when he was going to the doctor? I didn’t want to hear—I was just hysterical and insisted he take me home. He left me and went over to your folks’ house. They called me and begged me to let them explain. It was a very peculiar story, and I don’t recall all the details. But I remember the main reason—if it’s true. Curly said he had a wart on his penis and had to have it removed. Finally, he said, “If you don’t believe me, I’ll show you.” And he starts to unzip his pants, and I was a naive girl in those days and a virgin—there were such things, you know—so I said never mind. I didn’t want to see a bandaged penis.

JOAN: Was Curly fun? Some people have said he could be dull.

ELAINE: Well, he was fun. Especially when he’d get drunk.

JOAN: Do you think he was an alcoholic?

ELAINE: I don’t know. He never drank during the day, but occasionally I’d smell alcohol on his breath when he’d come home from the studio, and he’d say he’d had a beer. But at times when we’d go out—I can remember on the personal appearance tours—he’d get pretty high when we’d be in a nightclub. He’d take the tablecloth and pull it off and rip the fabric to the beat of the music. It was beautifully done—and the spoons, he played them very well. And, of course, the tablecloth was always on our bill.

JOAN: Did he like to dance?

ELAINE: I think he was a very talented man. He was very light on his feet. I was never very much into dancing. I was not a good dancer, and I don’t recall dancing with him. I must have, but I don’t recall.

JOAN: Did you ever see him read a book?

ELAINE: No, I don’t think I did. We didn’t have television. But he would study his scripts. It was such a short time that we were married, and most of that time he was either making movies or was on personal appearance tours. I really didn’t get to know him that well. And then the Stooges went to Europe.

JOAN: Yes, I was twelve when our father, Curly, and Larry went on a personal appearance tour of England, Ireland, and Scotland. [Pause.] Can you recall any interesting stories—funny or sad—that happened then or at any other time during your marriage to Curly?

ELAINE: [Pause.] There was one funny story. Curly and I were living on Edinburgh Street in Hollywood. I remember having a party, and Curly said I could invite all my friends. My friends and his friends were so entirely different. He didn’t have very many friends that I knew of—all associates from business. Anyway, we had this party, and the theme was gambling. Curly was quite a gambler. That was another thing we did a lot of. We’d go to ball games on which he’d gamble. He loved that—and the fights at the Hollywood Legion on Friday nights. So he put this Las Vegas night together with all my friends—whom I never saw again after that night. We played roulette and craps, and he took all their money—not intentionally, but the house always wins. [Pause.] I can’t recall any other funny situations. Most of my life with him wasn’t that funny—even the honeymoon. Curly took me to this dude ranch near Reno. I spent my whole honeymoon on horseback—and I hate horses.

JOAN: Then he liked horses?

ELAINE: I don’t think so.

JOAN: How did Curly feel about becoming a father?

ELAINE: I remember that Marilyn was born prematurely—and we were living in a house we were renting in Beverly Hills on Maple Drive. I don’t recall how he felt. He was away most of my married life. [Pause.] I remember one instance—before I had Marilyn. He had this dog. It must have been the dog your father gave us, and it had puppies. I remember getting in the car and driving all the way to Columbia Ranch in the Valley—where he was making a short—to tell him the puppies were born, and he was so thrilled. He really loved dogs.

JOAN: Wasn’t there any nightlife? After all, these were the golden years in Hollywood.

ELAINE: I don’t recall too much about what we did at night. I know he did a lot of running around. I was usually not included, and eventually I got very jealous of it.

JOAN: Did you enjoy touring with the Stooges?

Elaine with Curly’s first daughter, Marilyn (1938).

Courtesy of Elaine Howard Diamond

ELAINE: Curly wouldn’t let me near the theater. It was a horrible experience. He just didn’t want me to be in that atmosphere. I have a feeling that he put me somewhat on a pedestal because of my background—my parents.

JOAN: There are some men that treat their wives this way.

ELAINE: Well, sex was not so good with him. I remember once on a trip—an overnight trip—he was just awful because some man started to talk to me. And it happened to me several times when we were in a bar. If anybody started to talk to me he’d say, “Get upstairs.” He apparently was very jealous, and there was no reason to be, because I never looked at anybody else.

JOAN: Irma Leveton, my mother’s closest friend, once said, “I can’t imagine Curly saying ‘I love you’ to any woman.”

ELAINE: No, I can’t either. But apparently this pedestal he had me on kept our sex life quite poor. And of course this was my first experience. In those days we didn’t talk about sex.

JOAN: I’m sure Curly had had quite a bit of experience with women.

ELAINE: He was married before, you know. For a while they told me that the marriage was annulled. When Marilyn was born, I thought I had an illegitimate child and had my cousin, who was assistant district attorney in New York, check on it. I had to find out if I was legally married.

JOAN: I’d love to know where Curly married his first wife.

ELAINE: It was in New York, because they looked it up. It was registered as a divorce.

JOAN: How do you feel about mentioning that you were married to Curly?

ELAINE: I love it. I get a kick out of it. At work they—the kids who are now in their twenties—still watch Curly on Saturdays.

JOAN: Do you ever watch the comedies?

ELAINE: Once in a great while. Moe [my husband] will turn it on and say, “Come quick, Curly’s on.” The first time that I ever saw the Stooges’ stage show was on my first personal appearance tour [with Curly]. I’ll never forget it, Joanie. It was in Chicago. I was in the audience, and here I see Moe and Larry on the stage and your father poking Curly and slapping him and throwing pies in his face. I got so hysterical that they had to take me out of the theater.

JOAN: Hysterical laughing or crying?

ELAINE: Both. I couldn’t believe that I was married to that! You know, once he had cherry pits taken out of his ears from the pies. He had an ear infection—and the doctor examined his ear and came out with a pit.

JOAN: If you had it to do over again, would you have married Curly?

ELAINE: Well, it wasn’t the happiest time of my life. Another unhappy instance I remember occurred when the Stooges opened in George White’s Scandals. I was still married to Curly, and Marilyn was a year old, and he wanted me to come to New York. I remember it clearly. He sent for me—I went by train—and when I got off the train, he was waiting for me, and as I put my arms around him he said, “When are you planning to go back?” That was the way he was. He wanted something very badly, and as soon as he got it, he was no longer interested in it. Not only me but many things.

JOAN: Look at the houses. He went from house to house, dog to dog, car to car. A restlessness.

ELAINE: When he asked me to leave after asking me to come to New York, it was an awful feeling. A lot of it was not the most wonderful, romantic first marriage.

JOAN: Was he a kind man?

ELAINE: Yes—usually—and he was very generous. I remember once he bought me two mink coats. I think they might have been hot.

JOAN: Did he have a temper?

ELAINE: Not really. He was very good to my parents. My sister said to me the other day, “You know that Curly was very good to [our] daddy. He used to take our father to the fights, ball games, was very patient and sweet to him.”

JOAN: Did your parents like Curly?

ELAINE: Yes. But they objected to my marriage. They felt we were complete opposites. [Curly] always used double negatives in a conversation and, after all, I had gone to college. When we did break up, I tried in many ways to hold that marriage together. I went to a judge who had a reconciliation court in L.A., and I made lists of his [Curly’s] background and mine and went downtown hoping that he could help us, but it didn’t work. Several times I tried to go back to him after we were divorced. You have a little baby and you want her to have a father and have him share that. I think I even asked him once. He was the one that said no, that it wouldn’t work. It was probably for the best, because had I been with him when he got sick, I would never have left him. And he did become ill soon after that.

JOAN: Some people have said that Curly used vulgar language.

ELAINE: I think that’s maybe true, but around men—not around women. Today we do use that four-letter word, but I don’t recall him ever using [vulgarities] around me.

JOAN: What were Curly’s feelings about my father?

ELAINE: He had a very high regard for him. He idolized him. Anything that ever happened between us, he’d run to your father. I did the same thing—went to your father with my problems.

JOAN: Was Curly moody? Was his temper quick or slow?

ELAINE: I never recall him getting really mad. But I recall one time when I took our dog for a walk and he was accidentally killed. Neither of us ever said anything. But we both ran in different directions. I was scared of what he would do. I had no right taking the dog out. And he couldn’t face the fact—or face seeing that dead dog. He just ran. We both wound up at your father’s house, and that was when Moe gave us his little dog.

JOAN: You mentioned earlier living in Beverly Hills. When was that?

ELAINE: When Marilyn was a baby. We had a nurse, a chauffeur, and a maid who cooked—that’s a lot of help. We lived in Beverly Hills on Maple in a beautiful house. The year was 1938.

JOAN: Was Curly a complainer or did he ignore his problems?

ELAINE: He didn’t complain about his health. He didn’t have any problems when I was married to him.

JOAN: Did liquor change Curly’s personality?

ELAINE: Yes. Most people get happy when they drink. He got mean—very nasty. He’d push me around. He never hit me. I never saw him when he was that drunk, but he would slur his words and just get very belligerent.

JOAN: Did he ever seem sad?

ELAINE: The only time I saw him sad—he got stinking drunk—was when his mother died. I remember the Stooges were onstage, and when they came off, they were given a telegram. And instead of going up to his room—or being civil about it—he went with me to the hotel bar and proceeded to get extremely drunk.

JOAN: I feel he ran away from life.

ELAINE: Yes.

JOAN: Did his bad foot bother him a lot?

ELAINE: No. I recall seeing a big scar, and he would limp. I don’t ever remember him complaining about it.

JOAN: Was Curly well liked?

ELAINE: Oh, yes. They all loved him as a celebrity. Wherever we went, they wanted autographs and pieces of his clothing. They did that to all the Stooges. When we went to Atlantic City and he walked with me down the Boardwalk, he’d come home with half his suit missing.

JOAN: Do you feel the divorce affected Marilyn any way?

ELAINE: The only thing that I felt badly about is that she didn’t get to know Curly at all. She knew him only after he had those strokes, and she—the few times I brought her over there—she was afraid of him because he was so ill. Before that, when he was feeling better, he’d come to visit at our house and—after all, she was older by then—he’d bring her a little toy that was appropriate for a baby—a stuffed bear or a stuffed dog—so she didn’t appreciate the gifts he brought her. But he was very good-natured about it.

Curly and Elaine’s daughter, Marilyn, at the age of one. What incredible eyes! (1939)

Courtesy of Elaine Howard Diamond

I completed my taping of Elaine’s interview at her lovely Valley apartment. We kissed good-bye, and I realized that this book on Curly was becoming a catalyst that was bringing my family together again.

Sheet music from the famous Stooges “Alphabet Song” from Violent Is the Word for Curly (1938).

Curly poses for a family photo. Back row, left to right: Clarice Seiden, Moe’s sister-in-law; Curly; and Elaine. Front row, left to right: Bill Seiden, Clarice’s son; the author; and Shemp’s son, Mort (1938).

Publicity still from Flat Foot Stooges (Columbia, 1938).

Curly gives his customer a “pet-icure” in Mutts to You (1938).

Moe and Curly backstage in a dressing room at Columbia (1938).

Reminiscing about Curly with Elaine refreshed my memory about other humorous stories that my father had told me of their trip to Europe. In the spring of 1939, the Stooges signed a contract for an extended vaudeville tour of England and its provinces, including a two-week stint at the famous London Palladium.

Several weeks before his departure on the Queen Mary, Curly was worried about being a poor sailor and told Moe of his fear of getting seasick. Moe, who had done a lot of fishing in Sheepshead Bay, reassured Curly, insisting that he come out for a ride with him in the bay. They’d rent a rowboat and he’d get used to the water. For good measure, Moe would test an old seaman’s formula he had heard about and would wrap Curly in wet newspapers. Curly thought he was nuts and refused. Their rowboat ride went without incident, and Curly was positive the wet-newspaper bit was an old wives’ tale. Once aboard the Queen Mary, amidst the pitching and rolling of the high seas, Curly got violently ill. He raced throughout the ship, collecting newspapers, wetting them, and wrapping himself up like a fat mummy. But the old seaman’s cure was either ineffective or too late, and his nausea continued sporadically throughout most of the Atlantic crossing.

When the boat docked in England, Curly was amazed at their fabulous reception. He never realized that their films had preceded them for the past five years and that their British fans were legion. A few days later, in a scene reminiscent of Atlantic City and Curly’s problem with youthful fans, a group of pink-cheeked London lads leaped onto Curly and, before he knew what was happening, tore the pockets from his coat, grabbed his hat, and dashed off with their Curly souvenirs.

It is interesting to note that in the Irish language the word stooge is a slang term for intercourse, and throughout Ireland the boys were billed as the Three Hooges.

The tour was extremely successful, despite the fact that World War II began while they were in England and the entire country went on a wartime footing. The Stooges returned to the States on the Queen Mary’s last voyage before being converted to a troop ship. Immediately upon their arrival in New York, they started rehearsals for the Broadway musical George White’s Scandals.

Moe, Curly, and Larry in the dressing room, getting ready (1939).

Curly at the Dublin, Ireland, zoo with a feathered and nonfeathered friend (1939).

Moe, Larry, and Curly with fans on their tour of England (1939).

During the run of the Scandals, I can recall watching the show from the wings. There is nothing more exciting to me in the theater than viewing the performers from that space at the side of the stage between the wing and the act curtain. It always ran through my mind that if someone accidentally pushed me, I could be onstage—looking out at that frightening sea of faces with mixed feelings of both fright and delight. My uncle Curly was a pro, and he often told me that even he would get butterflies in his stomach at every performance until he knew the audience was with him.

As I watched Curly rehearsing onstage in 1939 for George White’s Scandals, I was able to see closely his cute, crooked, toothy grin when my father treated him sweetly and the sharp, comical contrast when Moe slapped him about; Curly’s mouth would open into a little circle, his brows would raise, and that funny mad-little-boy look would come over his face. Oftentimes, Curly’s inventive sounds and original mannerisms were used by him to cover up an inability to remember his lines. This was especially so in the Stooges’ films, where even his famous “woo-woo-woo” was created to cover up his memory lapses. In the Scandals there was a point in the act where the Stooges would each do a comical dance step, and Curly’s choice was always the shoulder-spin, which he executed on a filthy, splinter-ridden wooden stage, often getting a sliver or two in his ample buttocks. There are, to this day, many who believe that Curly was the original inventor of break-dancing.

This Columbia still photograph captures Curly during filming of Three Sappy People (Columbia, 1939).

Curly, with his faithful Havana cigar, poses with the other two Stooges for a publicity still for an installment of Screen Snapshots, a series of documentary shorts produced by Columbia (1939).

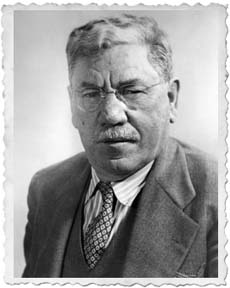

Portrait of Curly’s father, Solomon Horwitz (1939).

The Three Stooges mimic their three puppets (1939).

On this particular opening night, the Stooges walked slowly up to center stage dressed in the darnedest, crummiest conglomeration of formal dress imaginable: grey pin-striped pants; ill-fitting black frock coats; yellow, wrinkled, perspiration-soaked dress shirts; goofy black plastic bow ties; and funny little low boots called “congress gaiters.” Larry and Moe’s wardrobe fit sloppy-loose, while Curly’s fit him like a second skin stretched tightly over his chubby body. I was in the wings and probably more nervous than either my father or Curly. When Moe belted him with the flat of his palm, the slap resounded throughout the theater. Saliva flew out of Curly’s mouth, and I winced while the audience roared with infectious laughter.

The Stooges’ comedy routines onstage had a delightful touch of the corny that, because of the magic of Curly and the indefinable chemistry of their threesome act, would never fail to delight audiences throughout the world. The Stooges’ corn was plentiful. When my father would ask Curly what his occupation was, Curly would grin boyishly and answer, “I’m a tailor—and I can make you a beautiful suit with two pairs of pants and a belt in the back, including a vest, for only $675.” Moe would reply scornfully, “Six hundred seventy-five dollars! You’re no tailor, you’re a robber!” Curly would quickly retort in his cute falsetto, “That’s me, Robber Tailor!’ At which point the audience would roar. Then Moe, as a topper, would give him a resounding slap in the face or his traditional two-finger poke in the eyes.

Whether on stage or screen, Curly’s performance never ceased to amaze me. For a man of his size, he had the indescribable grace of a ballet dancer. When frustrated by Moe’s face slaps and eye pokes, he’d stand on his tippy-toes, staring eyeball to eyeball at his glaring brother, and he’d vibrate his arms like the flippers on a paranoid penguin. Then he’d mince about with his hands on his hips and, like a frustrated little kid, speak in the most ungodly high-pitched squeak, a voice that seemed incongruous coming from the mouth of a grown man Curly’s size.

On September 6, 1939, when the Stooges were a week into their stint for George White, Curly and Moe received word of their mother’s death. The two brothers were shocked at the news and deeply mourned her passing. Their only consolation was the fact that they had kept a major family secret from her. Jennie’s death saved her the grief of finding out that the apple of her eye—her firstborn son, Irving—had died three weeks before her.

But in the tradition of all performers, the Stooges knew the show must go on. And although the show did go on, Curly was beside himself, because he was unable to go to his mother’s funeral. The Scandals had a successful Broadway run, but Moe, Larry, and Curly were forced to leave the show before it closed and return to California to resume filming their shorts for Columbia.

Jennie and Sol proudly displaying a picture of their first son, Irving.

As usual, the Stooges took the train from Grand Central Station, and their departure was covered by the press. The following is an excerpt from a clipping found tucked away in my mother’s old yellowed scrapbook:

There was a knot of little boys on the chilly, station platform. “That one’s Curly,” one of them said importantly. Another saw a pal across the platform. He whistled shrilly and jerked his head with the old “come here” signal. The distant kid broke into a loping run. “Hi, Curly!” chirped the bigger one. “How about your autograph?” Curly was glad to oblige.

The kids stood around while the Stooges spoke to reporters. “Why aren’t they funny like they are in the movies,” one youngster asked. “Hey! What’s your dog’s name, Curly?” shrilled another kid. “Shorty,” said Curly succinctly.

With that Curly went to a newsstand to buy Shorty a paper to read for Shorty is a miniature schnauzer 5½ months old and such immature pooches are fond of newspapers for some reason.

Jennie Horwitz in Lakewood, New Jersey, in 1932.

Curly and Moe pose for newspaper photographers in Fall River, Massachusetts, with Curly’s newest dog, “Shorty” (1939).

Back in Hollywood for another forty weeks of filming, Curly went straight to the cemetery in Whittier, California, to visit his mother’s grave.

It is difficult to reconstruct how Curly felt at this point in his life. Moe once told me a story regarding Curly’s answer to a reporter who asked him how he felt about the loss of his mother. Apparently, Curly had been asked the same question many times previously and had his answer prepared. He reached into his pocket, pulled out a torn page from a magazine, and read: “One day as I sat musing, sad and lonely without a friend, a voice came to me from out of the gloom saying, ‘Cheer up. Things could be worse.’ So I cheered up and sure enough—things got worse.”

A few days later, the Stooges gave an interview where they reminisced about their trip to Europe and their visit to the Dublin Zoo. Whether said jokingly or not, Curly’s words must have reflected his innermost feelings:

Larry to Moe, “Aw, it ain’t so tough to be an animal. Think of the easy life they lead—no five shows a day, plenty of peanuts.”

“But what about their short life span?” Moe interjected, “Think of that, my boy!”

“Who wants to live long anyway?” Curly parried.

This was late in 1939, and little did Curly realize that he would no longer be living a dozen short years from then.