Varda’s Place Within Film History

After almost sixty years behind the camera, Agnès Varda’s filmography may not include any box office blockbuster (although Sans Toit ni Loi received a Golden Lion in Venice in 1985), but it has earned her a succès d’estime. After many years interacting with the audiences for her films and exhibitions, Varda is a well-known and established filmmaker at home (be it France or Belgium) and abroad. She has been fascinated by images for a long time, at least since she studied art history at the prestigious École du Louvre. Her interest turned into a profession when she started working as the official photographer for the Théâtre National Populaire (TNP), a famous French theatre company directed by Jean Vilar from 1951 to 1963. Her cinematographic career began by chance in 1954 when she decided to use a small sum recently inherited to make a film with Alain Resnais in Sète, a fishing village in the south of France. Featuring only two professional actors, Philippe Noiret and Silvia Monfort, and local participants found ad hoc, Varda and Resnais filmed and edited La Pointe Courte, an unconventional love story shot in black and white. After this first feature, she alternated between commissioned shorts like Les Dites Cariatides (1984), personal shorts such as l’Opéra Mouffe and 7p., cuis., s. de b., … à saisir and features like Cléo de 5 à 7 and Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse.

Studies by Sandy Flitterman-Lewis, Susan Hayward and Ginette Vincendeau have contributed to the recognition of Varda’s work, but their seminal analyses do not mean that Varda’s place in the history of French cinema is set in stone. In Henri-Paul Chevrier’s Le Cinéma de répertoire et ses mises en scène, for instance, Varda is swiftly assimilated with the Rive gauche group, then associated with feminist cinema in the 1970s, and finally described as a filmmaker practicing minimalist cinema (2004: 14, 90, 168). In her article ‘Who Killed Brigitte Bardot?: Perspectives on the New Wave at Fifty’, Vanessa Schwartz argues for a long overdue reconsideration of Varda’s work. She demonstrates how La Pointe Courte has been ‘sent to the morgue’ in most books written about the new wave (2010: 148) even if many characteristics of Varda’s first film clearly point to it as the inaugural new wave film. Schwartz’s analysis of this important exclusion is incisive and to the point: ‘To remember it [La Pointe Courte] would give too much credit, too early, to someone other than Truffaut’ (ibid.). Varda’s films are indeed often quickly pigeon-holed and interpretations like Chevrier’s are frequently based on incomplete and limited readings of her work, something that this book aims to remedy.

Because of her double status as a woman and as a filmmaker who did not belong to the Cahiers du cinéma group formed of Godard, Rivette, Truffaut and Chabrol who were ‘lumped together under the banner of the New Wave’ (Hayward 2004: 233), Varda has always been perceived as a bit of an outsider, a persona that the filmmaker has even cultivated for various reasons, including her desire to assert her individuality.1 Another reason for her debated place in French cinema and in its historiography is the number of films which were classified as either minor productions or of limited critical interest. These include Le Bonheur, L’une chante, l’autre pas/One Sings, the Other Doesn’t (1976), and her Californian diptych Mur, Murs and Documenteur. Recent scholarship, however, has re-evalued Varda’s eclectic body of work. Her ‘minor’ or forgotten films have recently been reconsidered and analysed as significant if often misunderstood feminist pieces (see Hottell 1999, DeRoo 2008, 2009 and Bénézet 2009 for more detailed analyses). The many re-edited and augmented DVDs that Varda has released in the last decade, and her recent foray into the world of contemporary art, has also attracted the attention of a growing number of scholars and cinephiles (see, for example, McNeill 2010 Chamarette 2011 and McMahon 2012).

My intention in this chapter is to reappraise a sample of selected films to argue that Varda’s cinematographic practice has always engaged with the corporeal, and that as a consequence it constitutes a decisive contribution to feminism. The three pieces chosen – L’Opéra Mouffe, Daguérréotypes and Les Veuves de Noirmoutier – were shot years apart and span Varda’s career. The first two films can be considered as part of the ‘cinéma de quartier’ (‘local cinema shooting’) that Varda frequently practices. Both were shot in Paris and focus on a well-defined space and its residents. The conditions of exhibition of Les Veuves de Noirmoutier were different from those of the two earlier films selected, but this installation piece makes for a more comprehensive and wide-ranging corpus.2 In spite of these differences, I will argue that all these films exemplify the central character of the body in Varda’s production and that Varda’s focus on bodies is politically significant.

1: L’OPÉRA MOUFFE

An essay between ethnographic and surrealist experiment

The scholarly reception of L’Opéra Mouffe is both interesting and revealing. Parallels have been made between this and later films, like Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse, on the basis of their shared concern for ‘the disenfranchised and the have-nots’ (Rosello 2001: 29). The autobiographical nature of L’Opéra Mouffe has been identified by Valerie Orpen, who describes the film as ‘a semi-autobiographical documentary, recording the altered and subjective viewpoint of a pregnant woman in the then-seedy neighbourhood of the rue Mouffetard’ (2007: 5). Despite these references, feminist critics and film scholars alike have largely avoided L’Opéra Mouffe, maybe because they found the film pretentious (see Tyler 1959) or essentialist (see Orpen 2007: 88).

Following Laura Rascaroli’s (2011) analysis, L’Opéra Mouffe is best described as an experimental and ‘essayistic’ work. It is shot in black and white with a 16mm camera. There is no synchronised sound because Varda had deliberately chosen to film alone. When she evokes the circumstances of this film, Varda emphasises the repetitiveness and independence necessary to carry out her project: ‘J’allais tous les matins avec ma petite chaise m’installer rue Mouffetard et je filmais’ (‘Every morning, I would take my little chair to the rue Mouffetard where I would get settled and start shooting’; Varda’s interview in the DVD Tous Courts edition). Each section of the film begins with a very short song followed by Georges Delerue’s music. The film is divided into ten vignettes, all introduced by intertitles (except the first one) in the manner of silent films. At the same time, L’Opéra Mouffe is resolutely modern as the film uses a musical soundtrack throughout, rather than a musical performance or a bonimenteur.3 In terms of narrative, there is a sense of continuity between some of the vignettes, but no direct causality between the film’s various sections. One of them focuses on a couple named ‘Les amoureux’, another titled ‘Des angoisses’ illustrates a pregnant woman’s anxieties. The juxtaposition of sequences like ‘Quelques uns’ and ‘L’ivresse’, showing people sleeping rough, with the more idyllic love scenes in ‘Les amoureux’ illustrates the contradictory feelings and anxieties experienced by the pregnant woman mentioned in the film’s subtitle: Carnets de notes filmées rue Mouffetard à Paris par une femme enceinte en 1958, commonly translated in English as Diary of a Pregnant Woman. Without veering too much in the direction of an interpretation solely informed by biographical information, it is important to underline that, in many interviews, Varda mentions that the film was in part a reaction to her subjective experience of pregnancy: ‘L’Opéra Mouffe was a short film about the contradictions of pregnancy. I was pregnant at the time, told I should feel good, like a bird. But I looked around on the street where I filmed, and I saw people expecting babies who were poor, sick and full of despair’ (Varda and Peary 1977). The alternation between the rêverie-filled diary of a pregnant woman and the more Griersonian-inclined vignettes showing La Mouffe allows L’Opéra Mouffe to develop into an essayistic film focusing on the corporeal.

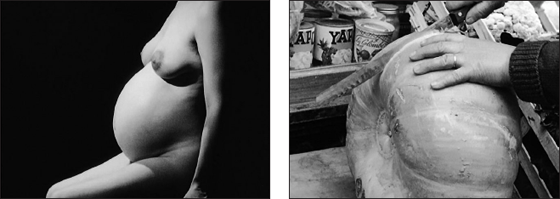

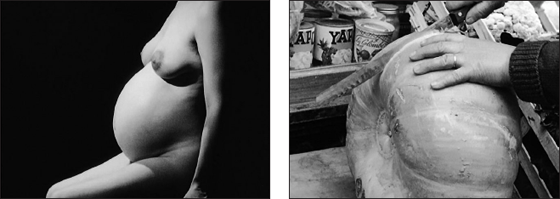

The fact that the spectator does not really know if the film has a plot line, or if it is based on free associations, makes it all the more enigmatic. The opening of L’Opéra Mouffe is a case in point. The names of the handful of people involved in the project roll over the image of a naked woman, sitting on a bench, her back to the spectator. The credit scene is immediately followed by a series of close-ups on the chest and belly of a pregnant woman. After a minute or so, a cut takes the spectator to the market where a pumpkin is cut open and emptied of its seeds to be displayed on a market stall. In refusing to show us the face of the woman,4 Varda makes clear that the film is going to present a collection of willingly enigmatic and ambiguous images rather than a set of straightforward representations. The captions may help but they are not doing all the work and neither are the images. The spectator immediately understands that he will need to be active to make sense of this particular film. Varda’s frequent use of close-ups satisfies our curiosity and desire to look closer to understand what we see. Her editing also helps, since it provides clues to interpret some of the film’s vignettes. But the spectator needs to get involved and to rely on their senses to make sense of the film. In the opening sequence, the analogy established between the pumpkin and the belly is obvious, if unusual. The juxtaposition of the nude close-ups and the violent removal of the pumpkin’s seeds makes the pregnant woman’s fears manifest and palpable. The contrast between the peaceful rhythm of her breathing lying down and the firm grasp of the hands slicing the pumpkin open could not be more telling. The physical reaction of the audience one often observes is the result of this sudden and surprising juxtaposition.5 Orpen’s reading of Varda’s nudes as ‘beautiful […] but never titillating [and] either staged, posed, […] abstract, or very playful’ (2007: 71) confirms my interpretation because the naked body here is meant to trigger a reaction but not one of visual pleasure. Varda shows the spectator how overwhelmed the pregnant woman of the subtitle feels when she considers the precarious nature of her unborn child. By compelling spectators to be active in their reception of the film, Varda increases their sensitivity to the minute details on screen; she forces them to tune in and to open up to evocative associations. Her close-ups of the belly of a pregnant woman are not meant to be titillating but to make the audience ponder and wonder at its perfectly round shape and at its slow movement as the woman inhales and exhales.

The mysterious pregnant woman the spectator is presented in the opening, in profile (left); an example of Varda’s striking juxtapositions: a pumpkin being cut open at a market stall which evokes the woman’s pregnant belly (right)

Another point that needs to be examined besides the combination of the evocative images with the film’s soundscape is the multiplicity of bodies in L’Opéra Mouffe. The opening of the film is a clear homage to surrealism and the artistic practice of collage. Unashamedly, the film also reminds the audience of its theatrical construction. The superposition of hand-drawn theatre curtains synchronised with the typical opening tap of a conductor’s stick at the very beginning is a playful nod to the spectators. This clever suturing of sound and images feels like the director is telling the audience: ‘Show time!’

The film’s opening is not only theatrical but also inventive and self-reflexive with its hand-drawn curtains and evocative soundscape

One of the most striking features of L’Opéra Mouffe (besides its meticulous editing and evocative soundscape) is the oscillation that takes the spectator from the crowds of La Mouffe to the sections devoted to the other two discernible female subjectivities: the radiant lover (played by Dorothée Blank) and the pregnant woman. But how are all these bodies orchestrated in the film? Are they simply edited to create an aesthetically pleasing portrayal of Paris in the late 1950s, or do they tell us something about that period in France? How significant is the treatment of these bodies on screen? Are the two women a sort of alter ego of the filmmaker, or do they have a different function? All these questions need to be addressed to establish the significance of the corporeal in L’Opéra Mouffe and the importance of the two women who are visually singled out in the film: the lover and the mother-to-be also need to be assessed.

The evocation of pregnancy in L’Opéra Mouffe is from the very start mysterious because we cannot clearly associate the nude shots in the opening with the pregnant woman present in the sections ‘Des angoisses’ and ‘Des envies’, or with Varda herself. In a double movement that conceals and reveals, this woman is turning her back to us and showing her bump. One could consider the vignettes associated with the mother-to-be as a subjective evocation of pregnancy, but if it is then it is clearly an evocation that Varda wants to experiment with. The fact that Varda does not play the role of the pregnant woman herself and that she keeps this film in the third person is important too. It underlines her determination to maintain a distance between her personal experience and the representation of pregnancy that she creates.6 Varda is neither composing a pamphlet on pregnancy nor simply presenting her subjective experience of pregnancy. Rather she invites the spectator to experience the vignettes associated with the mother to be as ‘little sensory haikus’ inflected by the music and songs as much as by her editing.7 In these, the association of certain images is telling as is the soundscape, which ‘when linked to the image […] provides and writes the narrative, directing, constructing, and emoting these words perceptually’ (Sinclair 2003: 27).

The dove, a recurring image in the film, is shown here struggling to escape from a fish bowl (left), while a young woman, running in slow-motion through ruins, evokes freedom and insouciance (right)

Four vignettes in total are related to pregnancy, namely the opening, ‘De la grossesse’, ‘Des angoisses’ and ‘Des envies’, but they do not necessarily follow each other. A sense of continuity is created between the opening and ‘De la grossesse’ through the image of the dove. In the opening, the cutting of the pumpkin occurs against the backdrop of tins, on which we can clearly read the word ‘La Colombe’ (‘the dove’). In ‘De la grossesse’, the singer’s four-line song includes the word ‘dove’ twice and we get to see a dove desperately trying to escape from a fishbowl. The close-ups of the bird’s physical struggle contrast with the apparent happiness of the young woman who is shown running in slow-motion in the long take that follows. She runs in a minimalist space, scattered with ruins and naked trees, her summer dress floating as she approaches the camera, as if she was embodying youth and freedom. Yet her insouciance is quickly tempered by the images that immediately follow. A sprout growing out of a cabbage cut in two and the image of a small doll in its cradle accompanied by the rhythmic percussion of a metronome-like sound evokes the impending deadline of a due date or of time flying fast. So she may look free, happy and as innocent as a dove, but this woman’s growing ‘bud under her skin’ (‘le bourgeon dans la peau’ of the introductory song) is what awaits her eventually.

The other two occurrences where we see the mother-to-be are different because she is heavily pregnant. In the section ‘Des angoisses’, a tracking shot follows her as she struggles to walk and carry heavy groceries. This scene is preceded by images of a hammer violently smashing light bulbs, followed by a hatchling struggling to get out of its shell. Again the image of the bird, here a baby bird, establishes continuity with the two sections discussed earlier. The soundtrack throughout ‘Des angoisses’ is a high-pitched, piercing whine. This incites the spectator to consider the sequence as a continuum, in which the violent hammering, the silenced chips of the fragile hatchling and the struggling woman are connected. This editing and clever use of sound makes the woman’s slow progress look all the more difficult and it certainly makes the spectator empathise with her. The woman’s slow physical progress is miles away from the picture of velocity and youth projected by the young woman running earlier.

In the other scene related to pregnancy called ‘Des envies’, the tone changes drastically when Varda manipulates the woman’s contrasting food cravings. The vignette starts at the market with several close-ups of the market’s offal and meat carcasses before it cuts and takes us to a florist’s shop. In a way, we have come full circle, back to the market, with its nature mortes even if, this time, the focus is on animals rather than on plants and vegetables. The pregnant woman walks out of the florist, carrying a bunch of flowers that she smells before munching on them. This scene illustrating her unexpected cravings is funny and light and its final position needs to be taken into account when analysing these two consecutive vignettes representing pregnancy. This scene’s humorous tone and the subsequent closing of a nearby shop’s iron curtain, followed by the intertitle ‘Rideau’, prevents the spectator from interpreting the film as a solemn and categorical project. L’Opéra Mouffe should be considered, on the contrary, as an irreverent and playful piece.

Varda presents us with various facets of the life of a young woman who is sometimes gay and happy, sometimes tired and gloomy. It is as if we were turning the pages of her rêverie-filled diary, which creates a perfect opportunity for the director to explore this woman’s sensual experiences and the potential of visual associations. In ‘Des envies’, for instance, she subverts the belief that associates pregnancy with food cravings by juxtaposing a series of unappetising nature mortes with the unusual consumption of flowers by the pregnant woman. At other times, Varda paints a grimmer picture of pregnancy as if the mother-to-be was overwhelmed by the transformation of her former self. The ‘Travail, famille, patrie’ motto of the Vichy government was not de rigueur anymore, but the late 1950s remained a pronatalist era. In ‘Des angoisses’, the physical weariness of the mother-to-be combined with people’s visible indifference (like the nun who does not offer to help and walks right past her) foreground the daily difficulties and unpleasantness associated with her pregnancy. Her changing shape provokes changes in the way she is looked at in the public sphere as well as in her sense of self. Her walk through nearly empty streets mimics the long process of adjustment that she has to go through. The unidentified high-pitched, piercing whine that accompanies the tracking shot where she is seen tottering and finally leaning against the wall out of exhaustion highlights her corporeal fatigue.

The pregnant woman munching on roses, an unusual case of cravings in the section called ‘Des Envies’

Varda’s decision to represent the challenges of this woman as she changes physically and the surreal associations that she establishes go against the traditional representation of pregnancy as an idyllic period. Rather than making a film that fits into the norms of an idealised and mythical version of motherhood, she highlights the difficulties that come with some of the changes that the mother-to-be undergoes when pregnant. Her realistic rather than idealised representation of pregnancy subverts many of the classical images of maternity. During the interwar period and well into the 1950s, female identity was associated with three competing images as Sandra Reineke explains in Beauvoir and her Sisters. These three competing images were: ‘the ‘modern woman’, who represented change from earlier gender ideals; the ‘mother’, who represented continuity and tradition and who served the state through sacrificing her body in birth; and the ‘single woman’, who oscillated between the other two, but more generally reflected postwar demographic concerns over France’s birthrate ‘in the absence of marriageable men’ (Reineke 2011: 12). These archetypes are interesting when looked at in connection with the two women in L’Opéra Mouffe since it could be argued that the film questions these stereotypes.

Varda’s vision is not political in the sense that her film does not advocate for the control of women’s fertility, but it does not support a pronatalist agenda either. Rather, it suggests that there is a plurality of ways to represent women and to evoke their experience on screen whether they are single, pregnant, married or not. Varda’s rejection of a fixed version of female subjectivity is in itself proof of her feminist stance. L’Opéra Mouffe is a playful and carefully crafted invitation to review the preconceptions held in the 1950s and engage in new perceptions of women. The images of Dorothée Blank, the radiant lover, are another symptomatic instance of Varda’s refusal to create a static and stereotyped version of the modern woman. Varda’s unconventional take on female subjectivity underlines ‘how ideologies of feminity are produced and re-produced in media representations’ (Thornham 2007: 7) and demonstrates that one can also create thought-provoking alternatives.

In L’Opéra Mouffe, Dorothée Blank’s character is associated with the idea of the modern woman in many ways. For example, a scene where she is passionately kissing one of her lovers is followed by a significant close-up on the word ‘la Moderne’ written on her Singer sewing machine. In the absence of dialogue and of a realistic soundtrack, all visual clues are crucial. The juxtaposition of these two shots is an example of how Varda’s editing establishes meaningful connections between specific images and ideas, here the naked lover and the modern woman. The sewing machine’s label is associating the lover with modernity and progressiveness. Surprisingly Dorothée Blank’s character is not as unambiguous as one may expect. Until the end, she remains an evanescent character whose story is left voluntarily undeveloped. We know nothing of her occupation, for example. For all we know she could be anything, an actress, a singer, or perhaps even a seamstress? We know, however, that she has three different lovers and that she lives by herself. The main difficulty for the spectator is that it is impossible to say whether the sections devoted to her are her subjective experience, rêveries, or even one of her lovers’ nostalgic recollections.

The most notable difference between her and the mother-to-be is that she is almost always associated with a man whether it is in her bedroom, in her courtyard, or at the market. So why is that the case? Is this emphasis on her couple(s) telling the film’s audience that she defies conventions and enjoys sexual freedom? Or is it asking us to question the meaning of the term ‘modern’ when associated with women? The only moment when she is by herself occurs in the courtyard where she is seen lying sideways on her bed and naked. Like the woman on the bench in the opening, she is turning her back to us, but here she looks absorbed and happy to be looking at her own reflection in a mirror. So is she performing what a modern woman is supposed to look like? Or is she simply enjoying her time alone in the absence of a male companion? And who is imagining this scene, her or someone else such as her frustrated ex-lover? In the two vignettes where she appears, ‘Des Amoureux’ and ‘Joyeuses Fêtes’, things are far from clear-cut.

Is this tableau an actress performing femininity, a mirror held to the spectator, or what a modern woman looks like according to Varda?

One way to interpret her character is to consider her as a free-spirited counterpart to the more contemplative mother-to-be. But overall her evanescent nature is meant to trigger our curiosity and to force us to fill in the blanks. Are her nudity and the way she interacts with her lovers ideal representations of love and heterosexuality, or a series of masks which reveals the director’s desire to question the performative nature of our own selves both in private and public? ‘Joyeuses Fêtes’ begins with a long scene showing children wearing masks and chasing each other. On a daily basis, our performances are certainly more subdued and less provocative than the childrens’ here, but they are part of almost anyone’s day to day life. Another way to look at this woman and her performance is through the perspective of the film. Dorothée Blank is indeed filmed in an almost self-reflexive way when her first lover plays with the lamp over her bed, when he puts her in the limelight and admires her face, so perfect and smooth before he turns the lamp off and they embrace again. Could this be a game of hide and seek not only between the woman and her lover(s) but also between the uncertain spectator and the definitely elusive young woman? Dorothée Blank, like Cléo, another of Varda’s beautiful heroines, has very little privacy and is constantly defined and circumscribed by the gaze of others. Her nudity is very much staged as are her appearances on screen. At the market, she stands out from the crowds of La Mouffe because of her beauty and because of her passionate displays of affection. On screen, she stands out because Varda juxtaposes her exceptional beauty and free sexuality with the nitty-gritty of the locals’ less glamourous daily life. In one of the bedroom scenes Varda, in a manifest homage to Man Ray’s famous Violon d’Ingres (1924), frames Dorothée’s back against the dark volutes of her iron bed. Visually she is all performance and plasticity, but ideologically she is a single woman whose ‘modernity’ I would argue is not yet acquired.

In a pronatalist society where women cannot freely control their own fertility, the choices available to this character remain limited. Varda’s representation of Dorothée Blank as an icon of modernity is in that respect only tentative. The label may tell us ‘la Moderne’ but it is on a tool, the sewing machine, associated with domesticity. Many external accounts testify to Varda’s political commitment and demonstrate that she strongly believed in women’s right to reproductive freedom. So looking at the way Dorothée Blank’s supposed modernity rubs against the representation of pregnancy and examining the alternative versions of female subjectivity offered in the film is essential. The creation in 1956 of the Mouvement français pour le planning familial (MFPF) alongside the women’s liberation movement and the radical doctors of the Groupe Information Santé (GIS) led to a push in the 1960s and early 1970s for free access to contraception and abortion, but none of these changes had occurred when Varda was filming L’Opéra Mouffe. So is Dorothée Blank’s character as free as she looks, or is she restricted by her legal rights? She may be the subject of gossip and admiration at the market, but the reality is that the more permissive image she projects should be carefully evaluated in the light of the period she lived in. Like the mother-to-be who has to live through a pregnancy that cannot be reversed, Dorothée Blank’s character is limited because she is a woman who does not have the same rights as men in France in the late 1950s. Like many women at the time, Varda was aware of the work of intellectuals like Jean Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. De Beauvoir’s much criticised The Second Sex published in 1949 also presents the body in ambiguous terms ‘oscillating between reductive biological stereotyping and critical elaboration of controlling cultural practices’ (Reineke 2011: 26). In De Beauvoir’s book, like in L’Opéra Mouffe, the corporeal may be at times ‘a burden’ as in the section ‘Des Angoisses’ and at other times ‘a marvellous double’ to be contemplated ‘in a mirror with amazement, […] a work of art, a living statue’ (2009: 672) as in ‘Des Amoureux’. Varda’s determination to question the corporeal and her desire not to limit herself to stereotyped versions of female subjectivity shows that L’Opéra Mouffe is as feminist as De Beauvoir’s writing.

But what of the other women (and men) presented in L’Opéra Mouffe? Now that Varda’s feminist position is established, why linger on the locals of La Mouffe? The locals do not simply provide an air of authenticity that counterbalances the more artistic and surrealist vignettes devoted to the pregnant woman and the radiant lover. They are doing more than adding couleur locale to the film. Rather, they further reinforce some of the issues discussed earlier in that they illustrate how varied female subjectivity can be. The fact that Varda’s montage compels the spectator to question his participation in interpreting film will also be looked at in this analysis of the residents and their role.

In the sections focusing on the locals of La Mouffe, there is a strong focus on women; women who are buying things, women who are trading goods and women who are talking to one another. Many of these women, especially in the opening vignettes are animated, talkative, as well as clearly curious. The market is shown as a place where they meet acquaintances, where they exchange news and gossip, and where they parade all dressed up in their furs and hats. It is both an economically important place and a public theatre where people perform and interact. Focusing on these daily exchanges and documenting these lives, even if Varda’s editing transforms them, is reminiscent of the theoretical move towards a more inclusive and less elitist historiography, which pays attention to the everyday as practiced by Michel De Certeau. By choosing this location, the filmmaker also confirms her ideological position: she wants us to focus on a path less travelled and more specifically on a neighbourhood less explored. Her interest in capturing the life of the rue Mouffetard is inscribed in the title itself: L’Opéra Mouffe. As the public space of the street stands at the core of Varda’s project, her film could be analysed as an ethnographic documentary on Paris in the late 1950s and on the role women played at the time. Her vision may be very personal, structured, and operatic, but the film undeniably contains ‘fragments’ of daily life in La Mouffe. The time of her shooting should not be undervalued either since the film documents life on this street in the winter of 1957, three years after the well-known winter of 1954. Reacting to a particularly alarming number of deaths on the streets, Abbé Pierre called for help on the radio and in the press in order to set up aid centres to help homeless people to survive the cold.8 So the bare branches of the trees seen in the lover’s courtyard, as well as near the buildings of La Mouffe should be regarded not only as a symbol of dormant life, but also as a reminder of the hardships experienced by many in Paris.

L’Opéra Mouffe may not be a film à message per se, but it is politically inclined, and it should be analysed both as a historical document and a more personal testimony. Despite the strict geographical focus and the short format of the film, Varda offers the audience a kaleidoscopic view of the neighbourhood at the time. We get to see the street market, the back alleys, the local houses as well as some of the shops of La Mouffe. The film’s oscillation between the subjective evocation of the pregnant woman’s experience and the documentary sections on the locals echoes Renov’s analysis of the new autobiography in the 1980s, when he remarks that this type of work: ‘straddles the received boundaries of documentary and the avant garde, [and] regards history and subjectivity as mutually defining categories’ (2004: 109). Varda’s complex editing and the lingering sense of mystery (even after several screenings) suggest that the woman’s experience (regardless of whether we take her to be Varda’s alter ego, or any French woman at the time) and the historical and social context are fundamentally intertwined and mutually defining. In the long tracking shot where the pregnant woman staggers under the weight of her groceries, several including Orpen have noted the importance of the graffiti on the wall which reminds us of the distant but no less menacing war in Algeria (see Orpen 2007: 17). In L’Opéra Mouffe, one cannot literally dissociate the private, the public and the historical as they are clearly intertwined. What Varda undertakes in this film is a poetic evocation of this neighbourhood’s history through the private and associational (of the diary). The avant garde character of the film may have prevented critics and scholars to consider it alongside other films of the period, but this would not be Varda’s first atypical piece.9 It is indeed as we have seen by now hard to categorise and tentative on many occasions. But it offers a provocative perspective through its particular soundscape and through its questioning of the fragile boundaries between documentary and fiction.

The fast-paced editing of some of the sequences devoted to the locals may give the impression that the director is solely interested in looking at repetitive behaviour, at people limping, tidying up their hair, or wiping their nose. But when examined carefully these vignettes are significant because of the variety of people that Varda includes in the final montage. The charismatic ‘causeuses’ who open the film at the market are as important as the slower and more contemplative shots of the other locals: the drinkers and rough-sleepers. In the vignette called ‘De l’ivresse’ where almost all the participants look back at the camera, the music and pace of editing suggest that we are dealing with a more meditative section, one on which we are supposed to pause. In ‘De l’ivresse’, regular drinkers do not seem to be considered by the market-goers as abnormal or out of character. They are simply part of the social fabric of the neighbourhood. But for all its apparent normality, there is one remarkable fact in the vignette ‘De l’ivresse’ and this is the inclusion of women. When showing women who drink alongside men, Varda chooses a transgressive image, one that is far from the romantic notion of ivresse often associated with love.10

This transgressive image is meant to provoke the audience and to trigger their reaction. Female alcoholism tends to be a secret and lonely practice (see Charpentier 1981) and medical discourse has often associated female alcoholism with underlying psychological problems, while male alcoholism is often seen as a ritual of male bonding and a sign of virility. So showing male and female locals together, as drinking equals and companions, is a levelling of gender, as well as a visual violation of the patriarchal construction of femininity.11 Varda’s vision is that women who defy society’s conventions should not be relegated to the periphery but included in a representative picture of Paris in the late 1950s. The song’s final two lines emphasise this idea of an inclusive examination of society, since it mimics the saying ‘Qui dort dîne’ (those who sleep will have dinner) with a humorous made up maxim ‘Qui boit dort’ (those who drink will sleep). At the same time, Varda creates a sense of continuity between all the Griersonian-inclined sections focusing on La Mouffe through visual echoes. Visually, the close-ups on the drinkers’ faces are reminiscent of the fixed gaze of some of the ‘gueules cassées’ (war veterans with severe facial injuries) encountered at the market in the earlier section ‘Quelques Uns’. Their gaze testifies to their awareness of the filmmaking process, and is similar to the shots showing the inquisitive nature of the women at the market. The locals may not perform like the actress Dorothée Blank, lying naked in front of a mirror or embracing her lover, but the fact that they are returning the gaze, if only momentarily, creates a disjunction in the narrative flow that compels the spectator to pause and think about his own participation and role. In her analysis of essay films, Rascaroli notes that this ‘constant interpellation’ whereby ‘each spectator, as an individual and not as a member of an anonymous, collective audience, is called upon to engage in a dialogical relationship with the enunciator, […] to become active, intellectually and emotionally, and interact with the text’ (2009: 35) is a defining feature of the film essay. This interpellation occurs in L’Opéra Mouffe time and again, and when it does not the absence of a realistic soundtrack titillates the spectator’s curiosity and compels her to compensate and engage with the images and music composed by Delerue.

Men and women drinking together in a Parisian bistrot, a documentary and subversive vignette

In the opening sequence at the market where Varda focuses on conversations, the intensity of these women’s facial expressions incites the spectator to try to imagine the subject of their spirited exchanges. We may not hear the women’s voices, but Varda’s close-ups on their faces and the mimicking of these women’s voices by brisk musical phrases alternating between woodwind and brass instrument provide a sense of immediacy and liveliness to the scene. The film’s changing soundscape enables us to examine how the music and songs suture images together and create the emotional world of diegetic involvement. Varda’s decision to do away with a realistic and synchronised soundtrack is what I would call inviting because the spectator can fill in this absence with whatever she wishes. Michel Chion, who writes extensively about sound, music and cinema, regards breaks, interruptions, and sudden changes of tempo (all practiced in L’Opéra Mouffe) as typical of an external logic of sound which ‘brings out effects of discontinuity and rupture as interventions external to the represented content’ (1994: 47). This is consistent with the form of the film essay in general as well as with its intention which is to make the spectator an intellectually and emotionally active participant. One can make sense of the different vignettes by comparing and contrasting them, by examining their order and tempo. But they could also be looked at as self-sufficient units, which are meant to trigger in the audience various impressions. Like in the opening where juxtaposed images create significant analogies, the music and songs’ rhythms and poetic contents defy expectations and produce strong reactions. At the end of L’Opéra Mouffe, the spectator is left to decide whether this film is about the cinematographic re-creation of a pregnant woman’s subjective impressions, the different ages a woman goes through (childhood, youth, pregnancy and old age), the inequalities and difficulties that afflict women in France in the fifties, or the daily life of the locals of La Mouffe. The spectator’s conclusion may very well vary from one screening to the next, but whatever it is, it will depend on her understanding of what the corporeal stands for in the film, on her conscious efforts to make sense of the images and on her (usually) unconscious interpretation of sound.

2: DAGUERRÉOTYPES

Manipulating stereotypes and enchanting daguerréotypes

(A) Daguerréotypes’ Working Bodies

Daguerréotypes was originally produced for television and later screened in various film festivals. Like L’Opéra Mouffe, Daguerréotypes focuses on a specific geographical location rue Daguerre, the street where Varda lives in Paris. The circumstances that surround the shooting are worth mentioning since they determine the format of the film. In 1975, Varda had recently become a mother for the second time and decided that her next project, a ‘carte blanche’ for the ZDF, a German television channel, would be filmed locally. The idea was that she would not go further than the eighty metre cable between the camera and her home allowed and that this would make it easier for her to look after her son Mathieu Demy. ‘I started with the idea that women are attached to the home. So I attached myself to my home, literally, by imagining a new kind of umbilical cord. I attached an electric cable to the electric meter in my house which, when fully uncoiled, turned out to be 80 metres long. I decided to shoot Daguerréotypes within that distance’ (‘Je suis donc partie de cette idée, de ce fait, que les femmes sont attachées à la maison. Et je me suis moi-même attachée à la maison. J’ai imaginé un nouveau cordon ombilical. J’ai fait tirer une ligne électrique du compteur de ma maison, et le fil mesurait 80 mètres. J’ai décidé de tourner Daguerréotypes à cette-distance là’) (Varda 1975: 39–40). When presented this way, the film is almost like an exercise de style, that is to say a formal experiment as much as a test.

Daguerréotypes has not attracted much critical attention from scholars. In a recent exception Kate Ince evokes the film but not at length to discuss important aspects of Varda’s work including her use of haptic imagery and feminist strategies (2012). My ambition is therefore to open the discussion by analysing the way Varda presents the body throughout the film and to show the political potential of this particular project.

Daguerréotypes is a film that is definitely part of Varda’s cinéma de quartier if only because of the technical limits that Varda imposed on her team and herself. It is anchored in rue Daguerre, in the vicinity of the filmmaker’s home, and intends from the start to offer the spectator a very subjective snapshot of the neighbourhood. Daguerréotypes is a film set in Paris as shown by the image of the Eiffel Tower in the opening shot, but it is also an original take on this street where magicians, musicians, hairdressers and tailors will be filmed as they work and live together. In the very beginning, Varda’s off-screen commentary reveals that she had always been mesmerised by the old-fashioned paraphernalia of the Chardon Bleu shop, but she also explains what her ambition is for this film. In Daguerréotypes she intends to trade her customer’s clothes to spend time on the other side of the counter. She wants to be inside the local shops with the shopkeepers as they spend their day working, waiting and dealing with customers. The shops that she has chosen to focus on are the ones most people went to on a daily basis in the 1970s: the bakery shop, the butcher’s, the grocery, and the quincaillerie (a kind of DIY-hardware store). To this selection of shops she adds a few more quaint places including a tailor’s workshop, a hairdresser, a clock-maker, an accordion store and a driving school. The local cafe is also filmed but not like any of the other shops. We do not know who the owner is and we are never taken in the cafe during its daytime opening hours. Scenes from the magician Mystag’s show held at the cafe are nonetheless crucial to the film since they are interweaved with the locals’ daily activities in the second half of Daguerréotypes. So the cafe is used as a centre of convergence and coherence, almost like a symbolic theatre where Varda can tie together the various strands of the story that she is trying to tell.

If we consider that Daguerréotypes is a picturesque portrayal of the neighbourhood articulated around the shops of the street, it is essential to consider those who own these shops as well as those who use them everyday. Varda makes no secret that her portrayal is going to be highly stylised and personal from the very start. Mystag’s definition of a ‘daguerréotype’ in the first scene of the film and the filmmaker’s confession that Daguerréotypes originates from her fascination and curiosity are blatant proof of this. So what sort of representation does Varda offer of her neighbourhood in this film? Are the local shopkeepers filmed all day and at work only? Or does she give them the opportunity to speak and participate in the project? And also, how is the corporeal of interest again in this specific film?

After explaining what she intends to do in the introduction of Daguerréotypes, the filmmaker makes herself more discreet during a series of longer sequences representative of the shopkeepers’s routines. This section is characterised by its stylistic sobriety and constructed as a ‘day in the life’ type of documentary. It starts like L’Opéra Mouffe with a theatrical lift of the curtains but the stars of the show are of a different nature, as Varda explains: ‘Au théâtre du quotidien les stars sont: le pain, le lait, la quincaille, la viande, le linge blanc, l’heure juste, le cheveu court et toujours l’accordéon’.12 The filmmaker takes the audience from one shop to another and shows us a series of uninterrupted exchanges between the shopkeepers and their customers. These exchanges illustrate both their expertise and their familiarity with most customers. The latter are varied and include an old lady who wants to buy condensed milk, two young men getting bread, and a mother and her child who want some laundry detergent and a toy. Whoever they are dealing with, the shopkeepers remain attentive and considerate even when they face unclear demands or long queues of people. The banality of these verbal exchanges may make them sound inconsequential but the camera’s long takes on the choreography of the bodies on screen is remarkable.

First, the camera lingers on the hands of the baker’s wife when she touches the bread to pick one with just the right crust, then it remains on them while she rummages through her drawer to find the exact change. Maria’s knowledge is literally hands on and filmed as such. Instinctively she knows when to ask about someone’s health and when to be more politely detached. The coming ins and going outs are punctuated by the door’s bell which creates an almost lulling sense of repetition. The position of her body slightly leaning towards the counter tells us that her routine is made of many moments of relative calm interrupted by short and to the point exchanges of goods for money. The slow ballet of bodies continues as the camera shifts its attention to another local couple who are opening their DIY store. Here, there are gas bottles to be taken out, panels and doors to be opened, items to be displayed on the pavement. In a dialogue-free long take that slowly pans from one partner to the other, the couple moves in and out of the shop, synchronised and in harmony. Their mutual understanding and effortless dexterity (probably achieved through daily repetition) highlights the couple’s dependence on each other. In all these places but the grocery shop which is operated by four Maghrebi men, the wives work alongside their husbands and play a fundamental role.13 The baker, who we have not seen at this point, utterly depends on his wife to tend to the shop. Similarly, the butcher needs his wife to settle financial transactions and to keep waiting customers happy. At the hairdresser’s store the space may be more clearly divided since female and male customers have a separate dedicated space, but the sound of magazines being flicked through and the ambient chit-chat illustrates the central role played by women in this business too. What the camera shows us is that these businesses rely on the harmonious choreography of both the partners’ bodies to strive and flourish. This equilibrium may not always be easy to maintain but the looping structure of this series of sequences which ends with the closing of the DIY shop and the same accordion melody shows the audience that women are as significant as their male counterparts in the life of rue Daguerre. Daguerréotypes makes them visible as much as their partners and points to their knowledge, dexterity and dependability. If one considers that this film constitutes a historical document which shows what the capital was like in the 1970s, then this sequence demonstrates that women play a critical role in the local economy and in society overall. They may be associated in the media with their home and children and in the world of advertisement with seduction, but in Varda’s film their bodies are as active as the men’s and firmly anchored in the world of labour.14

This first series of scenes focusing on a day in the life of a shop is not the only section of the film where the filmmaker adopts what I would describe as an affirmative and corrective viewpoint. In the first series of direct interviews, Varda asks the participants to tell her where they come from. She then draws the conclusion that, in this working class neighbourhood, many of the tradesmen are economic migrants who came from outside the capital, a practice which to this day is still called in French ‘monter à Paris’ (to go up to Paris). In doing so, Varda makes it clear to non-native speakers15 that these individuals who may have fitted their stereotype of the Parisian have in fact not been living in the capital for generations. This is a significant moment since it is the first time that Varda’s off-screen commentary rectifies a common misconception about Parisians.

In the second series of interviews, which interestingly does not focus on work, Varda asks each partner another apparently innocent question: how they met their significant other. Here two characteristics are of particular importance. First, even if the sequence is thematically linked by the specifics of the couple’s first romantic encounter, it is edited so that out of the six couples interviewed, only two men get to speak first: the owner of the Chardon bleu shop (whose wife is arguably not the most voluble) and the hairdresser. The women are therefore given pre-eminence in the sense that they are given the opportunity to articulate first how they met their husbands. The second notable characteristic of this series of interviews is that the men are the only ones who talk of not only love at first sight (in French ‘coup de foudre’) but also their children, while the women tend to be more factual and sometimes even sound blasé (the seamstress and Janine the hairdresser in particular). This subversive montage favours a representation of men that goes against the grain of traditional masculinity since they are shown as sensitive and more romantically inclined individuals (in particular Yves the hairdresser and the baker). This sequence is also worth mentioning because it is the first time that they share aspects of their private rather than professional lives. By focusing on the women’s key role in the day to day running of the shops and by letting them speak first when focusing on romantic encounters, Varda demonstrates that there are alternative and affirmative ways to portray the women of her street. She also shows that women need not be confined to traditional roles on screen and that they should be seen as sensible and articulate economical agents.

(B) Daguerréotypes’ Conflicting Images of Women

In this chapter, I have chosen to concentrate on three of Varda’s works which are not chronologically close partly because each of these films sheds light on some of the major social and political changes that occurred in France during the second half of the twentieth century. Varda’s career spans over fifty years and her conception of cinema and its role was most certainly affected by some of the social and political changes she experienced. Scholars have recently started analysing the intersections between personal and collective experience in Varda’s work. DeRoo’s article on Le Bonheur is for example a case in point, which demonstrates the importance of analysing films in relation to their cultural and social context. In exploring the film’s social and historical context, DeRoo demonstrates that Le Bonheur should be regarded as a subversive response to the dominant iconography representing women in the 1960s. Her essay, which uses archival excavation of imagery from magazines like Elle and Marie Claire, demonstrates Varda’s irony when she applies these representations to the ‘subjects, characters and poses of Le Bonheur’ (DeRoo 2008: 191).

The 1970s were a period of intense political debate and many historians describe the period as the culmination of the long sexual revolution (see Briggs 2012: 542). As a result, one may wonder if Daguerréotypes through its concern with the local is not also a politically inclined work. A short sequence claims that people from this end of the street refrain from discussing politics because ‘it’s not good for trade’, contrary to what takes place at the other end of the street where political manifestos and heated discussions are plenty. This disclaimer meant to justify the absence of political discussions on screen only illuminates the polarisation of the rue Daguerre. Besides, if one takes a step back to consider the range of women represented in the film, it is clear that Daguerréotypes not only surveys but also interrogates the different images of women that circulate at the time.

On several occasions in the film, Varda includes commercial images of women that appear on the covers of magazines. In the first ten minutes of the film, when a woman and her child walk past a newspaper stand whose prominent display includes Le Nouveau Détective front page, we clearly see a black and white full size photograph of a naked blonde, just as tall as the little girl who turns towards the camera. This juxtaposition is witty because of the contrast between the naked yet passive woman on paper and the inquisitive gaze of the child whose mother has wrapped up in many warm layers. It is also cleverly inserted less than a minute after a longer sequence devoted to two ‘causeuses’ whose conversation focuses on a local victim of domestic violence. So even if Varda is not making a direct connection between conjugal violence and the objectification of women’s bodies, she definitely suggests here that the proliferation and impact of these images should be questioned. And through this ‘cascade of free associations’ (Gorbman 2012: 55) she makes her subjective voice heard.

In the hairdresser’s shop, where women gather and talk, a variety of commercial images are on display. The glossy pictures of fashionable hairstyles epitomise an unattainable ideal of beauty and youth dictated by magazines. These women are embodying an ideal of conformism through beauty. Other images, notably those of a magazine like Jour de France flaunting La Bardot on its cover refer to a different type of aspirational icon that at the time symbolises sexual liberation. To a contemporary spectator, Brigitte Bardot may look all dolled up and as affected as the commercial pictures of hairstyles we see in the salon, but what she evokes is very different. The clichés attached to Bardot’s film persona are ‘her youth, modernity, confidence, and freedom. […] she was no pinup who acted but rather a moving picture star who could also be stopped long enough to be photographed’ (Schwartz 2010: 149). In Daguerréotypes, none of these images of women are innocuous. I believe that in this scene Bardot’s photo shows the kind of new attitudes towards women that are gradually emerging at the time, even if they occur in a traditional looking hair salon of the rue Daguerre full of chatty middle-aged women. Some of the images promoted by popular culture (including film and music) clashed with the more traditional and conformist view of feminine beauty held by some. The cultural popularity of sexualised icons like Bardot may not always have coincided with social acceptance in the 1960s, but this sequence suggests that in 1975 many things are changing, even if these changes are part of a slow and gradual evolution. Scholars like Dagmar Herzog have argued that the idea of a ‘long sexual revolution’ is a more accurate description of what was happening in France.16 Herzog also claims that the legalisation of the pill in France in 1967 was only part of a larger development of new attitudes concerning sex.17 So Varda’s attention to Bardot as a symbol of a new sexualised youth culture when inserted in the context of the local hair salon could suggest that, in the mid-1970s, people have put the clash of ideals behind them, and that they are ready to accept new political and social changes.

France Soir’s headline, or how French politics and the future of women irrupt in Mystag’s magic show

The most significant front page of Daguerréotypes is the one that the young figure skater holds for all to see during the magician’s show situated at the end of the film. On the cover of France Soir, the title is impossible to ignore: ‘Avortement, c’est l’heure de vérité’ (‘Abortion: now is crunch time’). The film may focus on the magician’s tricks, but this is a significant close-up, especially coming from someone who signed Simone de Beauvoir’s polemical manifesto four years before this film. In 1971, Varda signed ‘le manifeste des 343’ published in Le Point which called for the legalisation of abortion. Signed by three hundred and forty two other women including Marguerite Duras, Bernadette Lafont and Françoise Sagan, it read as follows: ‘One million women get an abortion in France every year. They’re doing it in dangerous conditions because they’re condemned to clandestineness, although medically controlled abortion is a simple thing. Everyone keeps silent about those million women. I declare I am one of them. I had an abortion. As well as demanding free access to contraceptive means, we are demanding free abortion’.18 At the time, Varda was involved in the feminist movement called MLF (mouvement pour la libération des femmes). With her friend, the actress Delphine Seyrig, she went to demonstrations and held meetings in her kitchen which are vividly remembered by her daughter Rosalie.19 So even if Daguerréotypes does not include any discussion of abortion per se, it certainly acknowledges the turning point that French politics has reached by 1975. This paper is much more than a part of Mystag’s magical trick, it is a window on the political changes which will affect the life of many young women like the figure skater and the butcher’s daughter. It is also a reminder of the commitment and struggle of militants who are pushing for this bill to be passed.

Daguerréotypes draws our attention to the variety of women’s images in the media, and the film itself captures a remarkable range of images of women. As explained earlier, the working body is central to Varda’s affirmative take on the role of women in society. In many other sections of the film, Varda also includes many other women such as the young figure skater who is both full of aspirations and determined, the enigmatic older Léonce (alias Mme Chardon Bleu), and the ‘causeuses’ and ‘concierge’ with their assertive opinions. These many participants contribute to the film’s narrative and show that women cannot be confined to a single reductive image. As the interviews clearly demonstrate, they come from different places and have had different experiences. Some are old and others are young. The only thing that ties them together is the fact that they live on the same street and that maybe some of the political aspirations of the older generation will become realities for the younger ones.

(C) A Non-Definitive and Self-Reflexive Take on Portraits

Varda takes a clear position in giving visibility to working women in Daguerréotypes. But her way of capturing the lives of the people of the rue Daguerre on film is far from being presented as a definitive take. Rather, she is asking the audience to look again, even if it is to look at something that they think they already know. She is also, I would argue, questioning the notion of the portrait and its claims to authenticity. When Varda decides not to edit out moments when the non-professionals of Daguerréotypes perform or when their body language acknowledges the camera, she invites the spectator to reassess what it is that they are watching. In most of the scenes focusing on the locals’ working day, the participants seem oblivious of the camera. They are seen chatting away with their customers and serving them as if nothing was out of the ordinary. Sometimes, however, it is clear that the camera is not as unobstrusive as it seems, like at the end of the first sequence in the clockmaker’s shop. In this sequence, the customer’s natural attitude and spontaneous banter have made the situation sound perfectly authentic. But after the clockmaker walks out of the frame to attend to something in the shop off screen, his wife is awkwardly standing behind the counter, visibly hesitant and furtively looking towards the camera, as if looking for a signal. Her posture reveals how the filmmaking process disrupts the reality of the world it is documenting. In this case, her body cannot lie, nor can it act seamlessly.

The other occurrences that remind the spectator of the documentary process generally coincide with sections focusing on the driving instructor. On these occasions, he sounds like he is performing for the camera and looks rather uncomfortable. His diction and tone of delivery in particular sound artificial. This is all the more surprising considering that a fairly long sequence is devoted to his classroom teaching, which one would expect should have prepared him to be more at ease than other participants in front of an audience. Could it be that these individuals who are visibly confortable in their shops when busy and working feel that they have an obligation towards the filmmaker and the camera? Did something happen that made them uncomfortable just before these takes? Varda’s decision to keep these moments of awkward stillness and indecision remind us that one of the film’s main subjects is the idea of the portrait.

The Daguerréotype was a photographic process invented by Louis Daguerre in 1837 which enabled people to make portraits or photos of landscapes. It required ten minute exposure and remained popular until the 1850s. Posing for the camera or acting in front of the camera is not necessarily an easy task, something that all will be doing naturally. In Daguerréotypes, Varda is experimenting with the idea of the cinematographic portrait and the end sequence which gathers several shots like ‘family photos’ illustrates this. Throughout the film, she is manipulating the codes associated with the portrait, and reappropriating them. She encourages the audience to pause and contemplate some of the following issues: how do the traditions and codes of portraits (whether pictural or photographic) affect her cinematographic project? How do you draw someone’s portrait on film at a time when television has become an established mode of representation? Do you need genuine shots of a person who is unaware of the process, or can you show their personality through interviews? And how does a long term relationship between the filmmaker and participants impact on the end result, if it does at all? When Varda establishes a contrast between the natural-looking activities of the shopkeepers and the corporeal hiccups, she points to something that I associate with Sartre’s description of the barmaid and other workers and his discussion of the ceremony that society expects from him. I will quote Sartre’s text at length here:

There is the dance of the grocer, of the tailor, of the auctioneer, by which they endeavor to persuade their clientele that they are nothing but a grocer, an auctioneer, a tailor. A grocer who dreams is offensive to the buyer, because such a grocer is not wholly a grocer. Society demands that he limit himself to his function as a grocer… There are indeed many precautions to imprison a man in what he is, as if we lived in perpetual fear that he might escape from it, that he might break away and suddenly elude his condition. (2003: 82–3)

In this passage Sartre eloquently demonstrates that in the collective imaginary specific roles are set for tradesmen. These roles and ceremonies are performed by the tradesmen’s bodies, through the way they walk, lean, talk. All impersonate the type of tradesmen that they are supposed to be. Could it be that in the scenes mentioned earlier the driving instructor finds it difficult to perform his role in front of the camera? When Varda begins her film, the audience probably expects a cinematographic snapshot of the street that will include such performances and ceremonies, and maybe even some stereotypes. Soon enough, however, the filmmaker requires her audience to reconsider their preconceptions by showing three important things. First, by focusing on the body of women at work, she incites the spectator to think about professional and social hierarchies in France in the 1970s. She makes the audience not only look at the repetitive nature of their routine but also at their reliability and intelligence. Secondly, by reframing the way these individuals and their bodies are represented on screen, she questions the idea of the portrait and links this back to earlier traditions and codes. Finally, by drawing attention to the effect of the cinematographic process, she makes a polemical statement and demonstrates that a documentary film can never be true to reality, and that in truth it is ‘a multi-layered, performative exchange between subjects, filmmakers/apparatus and spectators’ (Bruzzi 2006: 10).

Our perception and understanding of the corporeal in Daguerréotypes will depend on our experience and on our willingness to engage with the images and sounds that Varda mixes up. While sections of the film are voluntarily kept slow and ‘empty’ of dramatic actions (for instance the ‘day in the life’ opening), others force us to process an incredible amount of information. Mystag’s show for example requires that we reconsider the ‘professional’ sections, since we get to see all the tradesmen out of their shops. Drinking and smoking, chatting and laughing, they are in fact free of the ‘social ceremony’ their bodies are contrived to during the day, and they indeed look very different without their work clothes on. That evening in the café is exceptional; it is a turning point when they are asked to observe the magician’s rules. When Mystag asks Yves, the hairdresser, to relax before he hypnotises him into stillness, the roles are suddenly reversed. Yves is no longer the one asking his customer to lean back while he is busy trimming his hair. The filmmaker’s witty editing takes us unexpectedly from the butcher’s hands cutting meat to Mystag’s spectacular self-stabbing, and from the driving instructor’s lesson discussing the dangers of traffic to the trick where Mystag makes his assistant’s head disappear. These ‘professional close-ups’ that the spectator has sometimes already seen are reframed and given a new meaning when they are inserted throughout the show. What is performance and what authenticity? Is Mystag’s show the ultimate performance or a revelatory opening enabling the audience to see the participants’ true selves? Is this a show of attractions or a documentary?

The film’s final section focuses on the participants’ private lives, showing their homes for the first time. When Varda asks them about their dreams, she is definitely trying to get them to talk about something other than work. Many maintain that they cannot escape from work even in their dreams which are haunted by customers, students and mistakes. The butcher’s wife is categorical: ‘Rêver? On n’a pas le temps, le dimanche c’est télé et on dort!’ (‘Time to dream? We have none, on Sundays we watch TV and we sleep, that’s it!’). Others are more sentimental, nostalgic, and even original. The baker’s wife admits, for instance, that she makes funny dreams where she travels to different places even if she always wakes up in the same place, her bed, and needs to get herself ready to work. By enchanting their daily gestures, choreographing their bodies and giving them the chance to talk about their dreams, Varda lays emphasis on alternative aspects of the participants’ lives and personalities. She requires that we review our stereotypical expectations and engage with her film which she refuses to categorise but describes as a reportage and homage to her neighbours, the mysterious and outspoken locals of the rue Daguerre.

While the first section of Daguerréotypes is more observational, concentrating on the shared space of the street’s shops, the second half is more unconventional and ambiguous both in its content and style. The mysterious habits and mannerisms of Mme Chardon Bleu may have been exposed but they remain unexplained, the mundane activities of the tradesmen and their daily routine are known to us but all in all we know very little about their lives. Daguerréotypes is a tentative and self-reflexive film based on the enchanted and enchanting encounters that Varda creates in front of the camera. Its most valuable lesson is certainly in its reassessment of the polemical potential of the corporeal on screen.

3: LES VEUVES DE NOIRMOUTIER

(A) Un auto-allo portrait polémique et corporel

Scholars and critics alike have often described Varda’s cinema as autobiographical. There is no denying that some of the subjects she reflects on as well as her use of the voice-over suggest such a tendency, although a more detailed analysis of this particular device reveals that Varda often undermines and subverts the spectator’s expectations. Films like Jacquot de Nantes (1990) and Les Plages d’Agnès are undeniably linked with Varda’s personal experience. Yet, by interpreting these films as merely autobiographical, one misses the director’s interest in gleaning elements of a specific history and place as well as her personal impressions. In her analysis of Varda’s exhibition L’Île et Elle, Barnet rightly reminds us of this tendency: ‘The individual is linked to the collective, and vice versa, in a way that is always socio-political and highly charged with feminist influences. As Varda stated in 1975, and as is echoed in Les Veuves de Noirmoutier, ‘Je suis une femme mais je suis aussi toutes les femmes’ (Barnet 2011: 106).

The installation Les Veuves de Noirmoutier was created at the Galerie Martine Aboucaya in early 2005 and displayed at the Fondation Cartier in Paris from June to October 2006 as part of Varda’s exhibition L’Île et Elle. A week after the exhibition ended, Arte France broadcast a documentary film entitled Les Veuves de Noirmoutier based on some of the footage that Varda shot in preparation for the installation. The film, however, includes three additional widows and Varda’s intention in making it is clear: she wants to make these women not only visible but also heard outside of the restrictive ‘white cube of the gallery’.20 Since 2006, Varda’s installation has been included in many of her exhibitions such as Y’a pas que la mer! in Sètes (to which I will refer extensively since this is where I last saw this work in 2012).21 I will therefore be as specific as possible to support my analysis of Varda’s work in its particular context. In order to differentiate between the formats of this project I will use the following abbreviations: Les Veuves de Noirmoutier (I) for the installation, Les Veuves de Noirmoutier (F) for the film, and finally Les Veuves de Noirmoutier (C) for the catalogue published as an accompaniment to the 2012 exhibition in Sètes.

In her book Selfless Cinema? Ethics and French Documentary (2006), Sarah Cooper describes Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse as an example of ‘auto-/allo-portraits’. My objective in the first part of this section on Les Veuves de Noirmoutier will be to expand on this term to demonstrate that this work can be analysed as a corporeal auto-/allo-portrait. In the second part of this section, I will turn to the invisible to show how this work tries to make the intangible palpable.

Much has been written about the early and middle stages of women’s lives, up to and including menopause, but sustained feminist analyses of experiences such as widowhood, grand-mothering or sexuality in old age have been few and far between, and while the physical and emotional experiences of younger women are dwelt upon, there has been little attentiveness to those of the old. (Jordan 2011: 139).

Varda is therefore an exception since her work has for over a decade exhibited a sustained interest and engagement with the experiences of ageing, widowhood and mourning. Shortly after the release of Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse in 2000, Rosello expertly analysed Varda’s film as a ‘Portrait of the Artist as an old Lady’ (2001: 29–36). Shirley Jordan commenting on the same film wrote that it ‘calls us to witness the socially and existentially unpalatable textures of aging’ (2009: 581). So even if the experiences of the old have not received much critical attention, Varda’s concern certainly did not go unnoticed.

In Les Veuves de Noirmoutier (I+F), Varda continues her exploration of aging but takes it one step further, even if as often she refrains from offering a set definition of old age or widowhood.22 The dispositif of Les Veuves de Noirmoutier (I) (i.e. the audiovisual setting of the gallery space) confronts head-on some of the common assumptions made about widows such as their age. Just looking at the fourteen monitors around the central big screen, it is obvious that some of these women are still part of Noirmoutier’s ‘population active’ (or working force) like Inès Allorant, and certainly not retired. The multiplicity of the faces displayed on these screens illustrates the diversity that characterises this category. Varda does not confine her representation of widows to the stereotype of a lonely, wrinkled, white haired woman. Neither does she restrict her project to a series of interviews with alter-egos or look-alikes meant to reflect her own experience. On the contrary, Les Veuves de Noirmoutier (I) which touches on the personal and raw subject matter of bereavement for Varda is characterised by a meticulously planned audio-visual environment heaving with eclectic characters.23 Varda’s dispositif is elaborate and emphasises from the get-go the fact that widowhood can be perceived in a number of ways. In the room where the lights are dimmed, thus inviting the visitor to slow down and maybe sit for a while as in a theatre, fourteen chairs face fourteen small monitors arranged around a much bigger screen. While the central panel shows a nine-minute looped video of all the widows (but Varda) walking on the beach, each small monitor is reserved for one single female participant. To engage with each widow’s experience, the visitor needs to sit down and pick one pair of headphones to listen to a specific testimony. The oblong shape formed by the chairs corresponds to the configuration of the screens and a short description encourages people to move from chair to chair to listen to each widow. The space is large enough to allow other visitors to move around the chairs and circulate freely as they please.24

The big screen in the centre is different from the others since it is accompanied by a specific soundscape and more pictorial in its composition as noted by Chamarette (2011: 40). The fourteen widows, all dressed in black, gradually congregate and silently walk around a large wooden table incongruously placed on the beach à la Magritte. The sound of the waves on the sand is overlapping with the melancholy melody of Ami Flammer’s violin, but no words are ever pronounced during the 9-minute looped film. To Jordan, the central monitor represents and invites ‘the ritual exercise of grief, while also questioning the reductive construction of an entire social category’ (2009: 585). While I agree that Les Veuves de Noirmoutier (I) challenges the restrictive confines of widowhood, I would interpret this central screen slightly differently.

I see this video as an attempt to shed light on the difficulty of communicating grief and on the impossibility of portraying loss. The widows’ grief, which is explicitly referred to in many interviews as taboo, is given central stage here. The widows’ bodies take possession of the beach, a space more often associated with joyful holidays and romantic encounters. Their slow procession and resolute silence makes the scene both mysterious and poignant. The game of ‘chaises musicales’ and the circling that the visitor is meant to do in the space of the gallery echoes the slow-paced choreography of the central screen. To relate to these women’s experiences and to unveil the mystery of this central scene, the visitor needs to physically engage with the installation and to let the testimonies permeate him. The various positions that the visitor can adopt vis à vis Varda’s dispositif encourage her to question how included or excluded she feels from the scene that she is watching and listening. While the smaller monitors encourage the visitor to engage with the idiosyncrasies of each individual life and to meet the singularity of what Comolli calls a ‘corps parlant’,25 the big screen reminds us that no words can really approximate the widows’ difficulties and woes. Through its slow rhythm and morose music, this choreography of bodies summons a poignant evocation of the women’s pain. It also tells the visitor that these women should be given a space of their own in order not only to grieve, but also to remember and celebrate their lost ones.

The visitor who devotes a fair amount of time to watching the individual portraits will inevitably start to draw parallels. She will see echoes as well as differences between the widows’ ‘corps parlants’ and their narrated experience. Some women tell Varda that because their husband’s profession took them at sea for extended periods, they were already used to long absences and the feeling of an empty house. Others, like Inès, who have not gotten used to the absence of their partners or husbands, find this experience excruciating. Many of the women show incredible resilience and stamina. Several of them talk of the daily reminders of their husband’s presence; they show old photographs and tell of happy memories. When the flow of anecdotes carries the conversation towards other subjects, the camera’s attention often turns to the widows’ hands absently playing with their wedding rings, a visual reminder of their loss. These widows may not be sociologically representative because Varda’s sample is limited geographically, but many of the difficulties they talk about correspond to the concerns of people who want to improve the life of individuals and/or old people who find themselves in the same situation.