My objective in this chapter is to establish that Varda is a striking case of cinéaste passeur. The previous chapter aimed to demonstrate that auteurism is a valuable method when it adopts an encompassing definition of the filmmaking process. It also looked at how Varda subverts the concept of auteur in order to make it her own. In the current chapter focusing on Varda’s ethics of filming, my attention is focused mainly on what dictates her decisions when creating a film or setting up an installation. Relationality and connections are concepts often associated with Varda’s work. In ‘Varda: The Gleaner and the Just’, Flitterman-Lewis notices that Varda ‘as ‘author’ sees herself as an ‘intermediary who gives voice to those who have none’, including the Jewish children whose stories have never seen the light of official recognition’ (2008: 219; emphasis added). Jenny Chamarette (2012) also shows how Varda is concerned with the idea of subjective relationality. By drawing on selected examples, I will demonstrate that Varda’s cinema is remarkable because in spite of its eclecticism, it is characterised by an unwavering ethics of filming that requires delineation.

The concept of cinéaste passeur, which was developed by Dominique Baqué in reference to Raymond Depardon and Jacqueline Salmon, has not been associated with Varda’s cinema (2004: 186). A revised interpretation of cinéaste passeur however views the filmmaker as a mediator not only between the filmed subjects and the spectators, but also between a specific space and time and the moment of the screening. One of the difficulties when approaching Varda’s body of work is the need to take into account both her changing modus operandi and the dialectic between the location of shooting and the film.1 Varda is known for having filmed in a large variety of formats including personal documentaries, short commissioned films, feature films and more recently installations. By discussing contrastive pieces within her filmography as I did in the previous chapter with La Pointe Courte and Agnès de ci de là Varda, one can determine some of the defining characteristics of her ethics of filming. The two that I will focus on are her genuine interest in the encounter with the other, and her concern with the capture and preservation of images.

1: The Encounter with the Other

(A) Mur, Murs: A Collective Portrayal

Sarah Cooper (2006) underlines the dynamics of Varda’s films when she describes them as auto/allo-portraits. To demonstrate Varda’s understanding of cinema as a cooperative experience and to show that her films are based on encounters, I will focus on the example of Mur, Murs, which is the first part of her Californian diptych.2 In this film, Varda embarks on an exploratory journey to discover the people behind the colourful murals she comes across in Los Angeles. Varda interviews and films many muralists; she also questions their practice, their models, and some of their patrons. She investigates the historical and cultural roots of this phenomenon and its impact on the local communities. Finally, she also incorporates impressive shots of some striking examples of murals like Moratorium by Willie Herron. While most of the film focuses on the subject of murals, it also contains a number of digressions that relate more loosely to the film’s original topic.

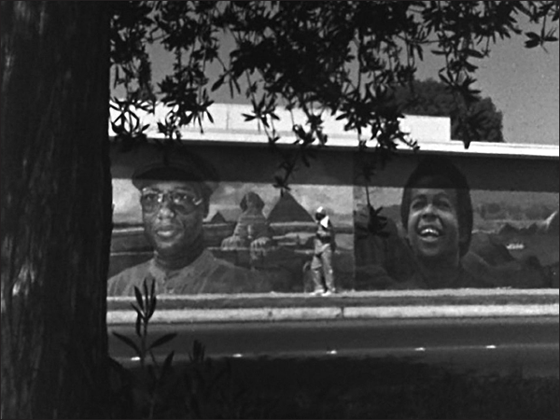

Mur, Murs is an interesting cooperative experience both in its form and in its making. In Mur, Murs, Varda’s vision of the city is shaped as a collective portrayal. She starts the film by explaining her original surprise and curiosity regarding this artistic alternative to commercial billboards. She then begins to interview locals and artists. Rather than focusing on a single aspect of the city, or a single representative individual, Varda uses murals as her starting point to explore the multiple facets of the city’s identity. Echoing the work of the artists she interviews, she creates a portrayal of the city based on the idea of the collective. In the off-screen commentary, she declares that the murals are peopled with typical Angelenos, that is to say ‘des noirs, des jaunes et des terres brulées’ (‘People with black, yellow and dust like red skin’). Varda’s colourful acknowledgement of California’s diversity exemplifies her attention to the heterogeneous identity of Los Angeles. In fact, both the Chicano and African-American communities constitute a salient presence in the film. This inclusion is hardly surprising considering Varda’s longstanding interest in political questions, as evidenced in her earlier documentary titled Black Panthers (1968).3

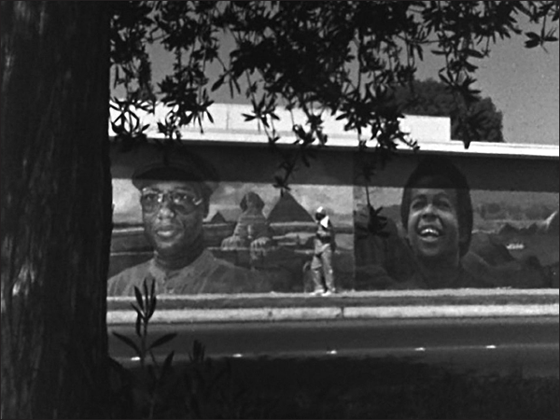

One of the film’s murals by Richard Wyatt, in situ

To some viewers, the film may be an unsettling experience because of the myriad of images and voices they are exposed to. Despite subtitles indicating the names of some of the participants, it is fairly difficult, if not impossible, to keep track of who appears, when they appear, and who says what. Varda records many of her encounters but chooses to present these in a complex and multi-layered manner. In Mur, Murs, Varda does not only assemble a visual patchwork illustrating her encounters with Angelenos, but she also creates a multi-layered audio commentary. Throughout the whole film, she adds a male ‘word whisperer’, whose voice is superimposed over her own off-screen voice, or over those of Juliet Berto and other participants. This lingering whisper gives the spectator a chance to identify the murals on screen, and to learn the name of their creators. This characteristic of the soundtrack subtly echoes the kaleidoscopic quality of the film. Mur, Murs’s almost dizzying assemblage of images is enhanced by the director’s play with the voices and music making up the film’s soundtrack.

Naturally, some muralists are only interviewed once, while others are allocated several fragments. This is the case of Judy Baca who introduces herself as ‘an artist, an educator, and a feminist’ and of Ken Twitchell whose work incorporates well-known figures from American popular culture. These sequences help the viewer to find his bearings. Yet, because of the number of participants overall, even these favoured interlocutors undeniably demonstrate that the shape of Varda’s film relies on the idea of the collective rather than on that of a single and oversimplified authority.

(B) Mur, Murs: A Tentatively Comprehensive Portrayal

The kaleidoscopic and polyphonic nature of Mur, Murs is not the only reason why I believe this film exemplifies Varda’s understanding of cinema as a cooperative practice based on encounters. Mur, Murs is not only a collective, but also a tentatively comprehensive portrayal of the city. Far from presenting a utopian or glamorous vision of the mythic city of Los Angeles, Varda presents a version of the place which includes both its local and lesser known facets. Varda’s comprehensive attempt is remarkable because it offers an alternative to the city’s bipolar imaginary, as defined by Julian Murphet: ‘According to your point of view, Los Angeles is either exhilarating or nihilistic, sundrenched or smog-enshrouded, a multicultural haven or a segregated ethnic concentration camp – Atlantis or high capitalism…’ (2001: 8). In fact, Varda lets all aspects of her interviewees’ urban experiences imprint the film. For example, she does not shy away from the practical issues that some of them experience on a daily basis. Violence and gang fighting are, for instance, addressed several times. Rather than assembling a coherent group of testimonies in the editing room, she incorporates in the film several interviews with diverging opinions, which invite the viewer to engage with the debate presented on screen. In doing so, Varda proves that her project is about capturing the multiple facets of the city, however contrasting these may be. The film as a whole is a project open to the different traits and voices generated by this place.

The inclusion of many interviews with artists from the Chicano and Afro-American communities testifies to Varda’s efforts to give the viewers a comprehensive representation of Los Angeles. The film includes the traditional have nots or laissés pour compte who are not often included in glitzier representations of the city. Flitterman-Lewis’s interpretation of Mur, Murs as a typical example of Varda’s political documentaries confirms this.

Salut les Cubains! marks the first of a long list of political documentary films, both short and feature-length, that Varda has made throughout her career. Her consistent commitment to the Left, and to the struggles against oppression in any form – political, economic, or social – has led her to treat a broad range of topics in these films, from the Black power movement in California (Black Panthers, a 1968 film dealing with the Oakland trial of Huey Newton) and the Vietnam war (Loin du Vietnam, a collective film in episodes made in 1967), to the situation of Greek exiles in France (Nausicaa, a 1970 television documentary using actual Greek exiles in a fictional chronicle), the Hispanic community in Los Angeles (Mur Murs, a 1980 ‘look’ at the murals in Los Angeles and their sociopolitical context), photography (Une minute pour une image, 1983, a television documentary of 170 ninety-second films, each about a different photograph), and women’s liberation (Réponse de femmes, 1975). (1996: 230–1)

While I agree that Mur, Murs is a politically oriented production, I believe that confining it to the category of ‘political documentary’ is too restrictive. I would argue that in Mur, Murs the notions of testimony and exchange are just as important as those of political engagement and activism. Varda’s interest in the city of Los Angeles does not only lie in its politically determined dimensions, but also in its social components. The collective and comprehensive qualities of the film demonstrate that the director is interested in assembling a thorough exploration of Los Angeles informed by her various encounters with Angelenos.

Varda’s editing offers further evidence for this interpretation. The focus of Mur, Murs is undoubtedly the murals. For that reason, the muralists interviewed by Varda have a specific status in the film. However, many other people on screen have no direct connection with murals. Among these participants, there are teenagers who happen to live in one of the barrios Varda films, musicians and singers, an old woman, a baker, a bartender and many passers-by. Because Varda’s editing includes these ordinary people, it reveals her desire to make a comprehensive portrayal of the city that gives voice to its various inhabitants. These sections of the film illustrate what De Certeau calls ‘the ordinary’ and its innumerable ‘obscure heroes of the ephemeral’ (1984: 256). The presence of these participants cannot be justified vis à vis the plot line or the main subject. These interventions illustrate Varda’s attention to marginal and atypical encounters. In interviews, she often explains that her approach to filmmaking is intuitive, while her editing is much more controlled: ‘When I film, I try to be very instinctive. Following my intuition […] Following connections, my association of ideas and images […] But when I do the editing, I am strict and aim for structure’ (Chrostowska 2007). A particular episode captures this characteristic of Varda’s practice and also shows her acceptance of chance as a potentially generative force when filming. At one point in the film, Varda is interviewing a participant when an accident between a motorbike and a car suddenly occurs. Instead of discarding the footage where the motorbike appears, Varda lets the camera roll and includes the unexpected experience of the crash into the film.

Finally Varda’s choice of participants also speaks volumes about her ethics of filming. Even with a focus on Los Angeles’s murals, Varda could have opted for more renowned participants. Some of the muralists interviewed have gained recognition today, but at the time of filming, most of them were relatively unknown. Varda did not care about the fame of the artists featured in Mur, Murs. She wanted the viewers to meet Angelenos in the flesh, whatever their occupation or origin. This genuine attention to the lives of others is the reason why Varda can rightly be considered a ‘cinéaste passeur’, that is to say an artist who truly wants to make the audience share her encounters. Her ambition is to capture the spontaneity of these encounters, which will, once collected and edited, constitute her films:

En regardant les gens se mettre en scène eux même, en les écoutant parler comme ils parlent, en observant les murs, les sols, les campagnes, les paysages, les routes, etc., on découvre tant de variétés entre le ‘à peine vrai’ et ‘le surréel’, qu’il y a de quoi filmer dans le plaisir. En fait on pourrait presque dire que le réel fait son cinéma! (By looking at people acting naturally, by listening to them when they speak, by observing the walls, the ground, the countryside, the landscapes, the roads etc., you discover the incredible variety there is between what is ‘almost true’ and ‘completely surreal’. And all this generates real pleasure when you film something!) (De Navacelle et al. 1988: 46; author’s translation)

(C) Mur, Murs: A Portrayal Focused on the Encounter of and the Exchange with the Other

While Mur, Murs has been interpreted with reason as a political documentary (see Flitterman-Lewis 1996: 230–1), the fact that it reflects overlooked experiences and tells unconventional stories about Angelenos shows that this film is more than a mere snapshot of California’s muralist movement in the 1980s. In fact, I would argue that Varda’s encounters form the core of the film, and that her focus on these encounters echoes the practice of filmmakers who engage fully with the film’s participants, like the pioneers of cinéma direct in Québec, Claude Jutra and Pierre Perrault. Vincent Bouchard’s study of the poetics of relation in the work of Jutra and Perrault is particularly à propos when one examines Varda’s films: ‘Le tournage est l’expérience d’une rencontre avant d’être un événement cinématographique’ (‘Shooting a film is above all the experience of an encounter. And that even before it is a cinematographic event’) (2005: 86). In Mur, Murs, the testimonies of Angelenos prevail over a deceptively objective presentation of the city. The dynamic of the film is determined by the encounter and the relationship between the filmmaker (or her alter ego on screen, Juliet Berto) and the participants. The participants seem to lead the director from one neighbourhood to another and from one idea to another. By association and jumps, the spectator is led through the city, discovering new spaces and listening to the voices of locals. Mur, Murs can therefore be seen as a collection of valuable images that testify to the collective experience between Varda and the participants.

The experience of meeting and filming Angelenos is simultaneously presented as precious and fragile. This experience is shown in its variability: things may happen that the director has neither planned, nor hoped for, as well as in its fugacity: people may die, or not be present when she assumed they would. This is the case with the muralist John Wehrle who she wanted to film, but could not in the end meet. In the off-screen commentary, Varda explains that because she was unable to film Wehrle, she decided instead to use the recording of their conversation over the phone. By including traces of her research, Varda reinforces the spectator’s attention to the tentative quality of the film. There is no certainty whatsoever when a project is still a work in progress. The film relies on financial means as much as on circumstances which vary according to the director’s exchanges with others. Often in Varda’s films, what matters the most is the recording of the fugacious moments which testify to her connection with others. As Froger writes: ‘Le film est le moment et la trace d’un don et d’un abandon où l’image, en tant que donnée, importe moins qu’en tant que chiffre d’un acte qui atteste du lien à l’autre’ (‘The film is both a special moment and the trace of a gift and abandonment, during which the image, as an indexical document, matters less than as the trace of a connection with another person’) (2004; author’s translation). Varda’s attempts to establish a special relationship with her participants is visible in her documentary films such as Mur, Murs, Daguerréotypes, Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse as well as in some of her installations like Les Veuves de Noirmoutier. When filming these encounters, Varda favours cooperation and spontaneity and makes the choice of revealing hiccups and surprises.

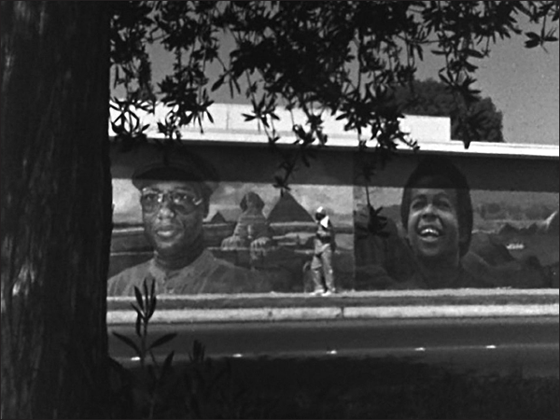

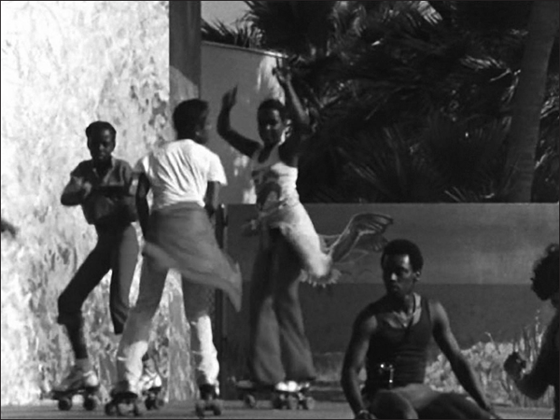

In Mur, Murs, Varda is a ‘cinéaste passeur’ insofar as she records the unique character of these encounters. The old woman who out of the blue starts singing when she is asked what it was like to grow up in the local neighbourhood is a brilliant example of the unexpected yet cooperative dynamics typical of Varda’s work. These moments of exchange make the connection between the filmmaker and the filmed participants tangible. This woman’s response certainly took the director aback when it happened. However, its inclusion in the final cut illustrates Varda’s acceptance of unplanned events and spontaneous reactions. This type of moment makes the supposedly strict boundaries between documentary and fiction vacillate. Some of the questions spectators are faced with are: is Varda really telling these people’s stories, or does she fictionalise her interviews? Do her interventions undermine our reception of the film, or does her presence facilitate the transmission of that particular experience? I would argue that the dialogues we see on screen, and the questions Varda leaves open prove that she neither imposes an omniscient point of view, nor pretends that she is completely objective. She recognises that cultural productions are affected by the artist’s subjectivity. In the opening of Mur, Murs, she makes this point clear by stating that the film originates from her curiosity about murals. At the same time, the diegesis quickly departs from this subjective stance in order to follow a journey dictated by the hints and suggestions of the locals. In her analysis of Varda’s work, Cooper confirms this when she writes that the director privileges a ‘position of non-knowledge’ and refuses a ‘hierarchical separation from her subject’ (2006: 88, 89). The way the participants respond to Varda’s project is formative. Varda will let these encounters and discoveries lead her in different directions. As a consequence, Mur, Murs gains a multi-layered quality that may, as mentioned before, leave the spectator in a state of uncertainty, speculating once it is over what the film was really about. Mur, Murs’s openness and its constant referral to others encourages us ‘to relate to the bodies on the screen by evoking our own history’ (Mai 2007: 143). The few scenes in which Varda records ambient sound or uses music as opposed to interviews are often full of action and movement: children running and playing with firecrackers, groups of people dancing and rollerskating. There is a definite invitation to make the spectators engage with either the recorded words of Angelenos or with their embodied experiences. Varda’s enterprise is not only about meeting locals, it aims to make us share these experiences.

One of the many musical scenes in the film. Here, dancing rollerskaters in Venice

Some of her comments on Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse make obvious the importance she attributes to the encounter and to its passing on:

this kind of film has two very important things for me: it really deals with the kind of relationship I wish to have with filming: editing, meeting people, giving the film shape, a specific shape, in which both the objective and the subjective are present. The objective is in the facts, society’s facts, and the subjective is how I feel about that, or how I can make it funny or sad or poignant. Making a film like this is a way of living. (Varda and Anderson 2001: 26)

2: Capturing Time and Images

(A) Mur, Murs and the Preservation of Images

Varda’s particular affection for art history’s classical iconography and her debt to photography is visible in films like Salut les Cubains! whose motto is ‘When Photos Trigger Films’ (Chrostowska 2007: 124) and Cléo de 5 à 7.4 My objective here is to expand the corpus traditionally favoured by scholars to establish Varda’s consistency throughout her career and to analyse selected examples in detail. The concept of trace mentioned in Froger’s quote cited earlier is central to understand Varda’s ethics of filming. Unless the director keeps a visual or written diary during the shooting, the film that the spectator watches is the only material trace of these encounters.5 Jean-Louis Comolli, a prolific analyst of documentary films, explains that cinema is supposed to bring back to life (for the spectator) the ‘here and now’ of the meeting between the filmmaker and the documentary’s participants.6

Roderick Sykes and Susan Jackson in conversation in St Elmo’s village

In Mur, Murs, Varda films the ‘here and now’ of her encounters with many different Angelenos. She films her meetings with muralists and passers-by; she also films some of the locals involved in the painting of these murals. She does not hesitate to linger when dealing with specific places. For instance, she devotes a full sequence to St Elmo’s village and its festival. In the mid-1960s, visual artists Roderick and Rozzel Sykes decided to rent some of the dwellings on St Elmo Drive and to transform this environment into an art space, where they could organise exhibitions and welcome local children and adults to explore and develop their creativity through art. This project provided locals with art workshops and underlines the vital connection between a specific space, its inhabitants and art. All these examples show how fundamental spending time with, listening to and speaking to Angelenos is to Varda. The fleeting but frequent images of children also confirm that live recording and local shooting are vital qualities for Varda.

In filming the ‘here and now’ of these encounters, it is obvious that Varda means to lay emphasis on the fleeting nature of this ‘being together’ and on the question of time more generally. An interesting parallel can be drawn between her encounters with Angelenos and her discoveries of murals, since they share a certain transient quality. The fact that murals are an ephemeral art form, that they are frequently destroyed or erased, and finally fade into oblivion make the collective experience of painting them, and their public enjoyment (for the time they are visible) the main point of the murals. During the course of the film, Varda underlines this particularity several times.

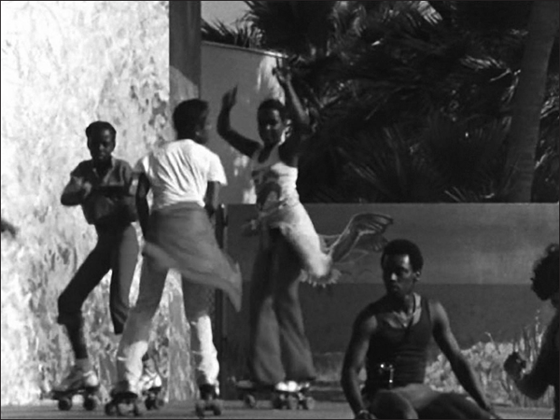

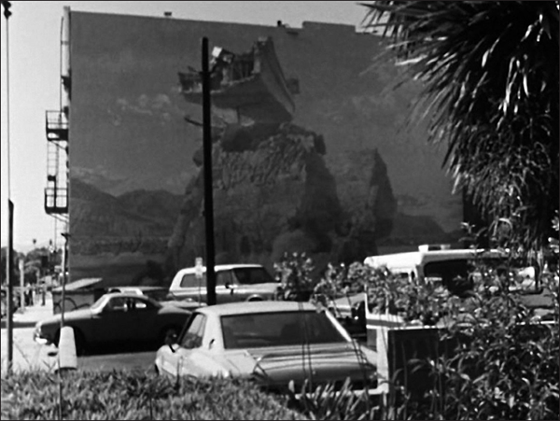

Among the artists interviewed many, like Arthur Mortimer, acknowledge this ongoing process: ‘Mural painting is ephemeral by nature, murals fade, they are mutilated, they change with time, and this is all part of their beauty.’ But to him and other artists, it is more important to paint ‘vital art’, where it is most needed, than to produce collectible pieces. This is precisely where Varda’s project accomplishes the unexpected, since she literally lends these murals a lasting value for as long as copies of her film are available for screening. She truly becomes a ‘cinéaste passeur’, because her film keeps material traces of the murals, even if their preservation is uncertain. By documenting these murals, Varda freezes them in time and anchors them in history. By making their appreciation possible for thousands of potential viewers, she makes them durable. The mural that opens the second opus of Varda’s Californian diptych, The Isle of California painted by Victor Henderson and Terry Schoonhoven, only exists now as a faint shadow because it was painted in enamel on stucco. The irony is that this particular mural represented the city in ruins, and that Schoonhoven’s work is concerned with destruction, time and death. ‘The L.A. of Schoonhoven’s imagination has collapsed its own future into its present; that future has the iconographic properties of various possible California apocalypses, but in the end it is beyond questions of right and wrong, being simply, in the romantic American mode of Poe and Whitman, Death’ (McClung 2002: 219).

The Isle of California by Henderson and Schoonhoven before its destruction

When Varda films her personal experience in Los Angeles, she returns to the essence of cinema, or at least to one of its essential characteristics, as Comolli puts it: ‘le cinéma filme du temps, fabrique des durées, les fait expérimenter, c’est à dire vivre par le spectateur’ (‘cinema captures time, constructs durations, and it enables spectators to experience these moments’) (1997: 36). Varda indeed films time as it is passing by, and as it is affecting murals and changing people, in short as it is mechanically recorded on film, in its inherent irreducibility. Several examples come to mind, which all evoke this idea of fugitive time. When she shows certain murals like The Great Wall, or Bride and Groom by Twitchell, the long process it took to paint them is mentioned, sometimes even illustrated by still photos made during their execution. Of course, what is visible at the time of Mur, Murs’ shooting is only the end result, but by detailing the step-by-step composition of these murals, Varda highlights the notion of time and the efforts that were necessary to make these projects happen.

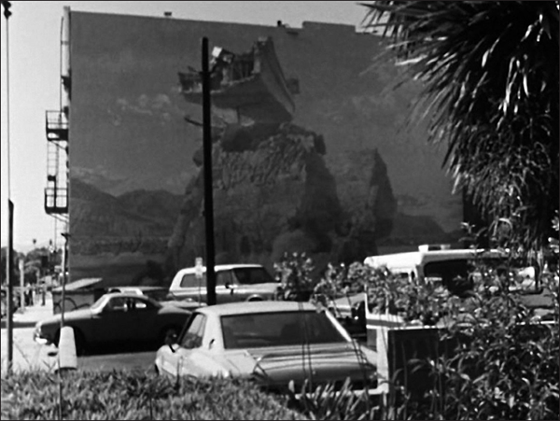

In other cases, Varda privileges ordinary people (and not artists) to illustrate the idea of time. The sequence devoted to Betty Brandelli is brief yet telling. Betty is interviewed standing in front of a particular mural, a configuration repeated several times throughout the film. On Mortimer’s Brandelli’s Brig, Betty and her husband are represented standing side by side in front of their bar in 1973. Since then, Betty has changed physically and her sitting in front of this image makes for an unusual collusion of times. Her husband’s absence, combined with the towering presence of the mural, makes her look frail and isolated. Her candid look at the camera and her explanation that her husband has passed away are direct reminders of the time elapsed between these two moments. Following this revelation, the camera zooms out and reveals a wider shot showing Betty surrounded by the lights and microphones that are being used to film her. Looking a bit lost, she visibly hesitates about what to do next, and finally gathers her things before leaving the set. This almost brutal episode is a striking example of the way Varda makes the viewer realise the ephemeral character and the fragility of any artistic practice, and of those who partake in their elaboration. This sequence seems to echo some of Varda’s preoccupations in her later installation Les Veuves de Noirmoutier (2005). ‘Time and mortality are central themes to [Varda’s] work’ (Beugnet 2004: 286) and this type of sequence shows that many points of convergence exist among Varda’s otherwise eclectic films. She knows that she cannot change time, however manipulative and ingenuous she may be in her editing. Nevertheless she can decide to link sequences in a certain way, and to point her camera towards subjects outside of the dominant commercial trends. Mur, Murs is a case in point of her desire to collect images of a specific time and place. An analysis of her attention to capturing images of the margins is therefore called for to fully understand her ethics of filming.

(B) Capturing Images of the Margins: Ethics and Praxis

Varda’s work has been associated with many different categories including la nouvelle vague, the political film (see Tyrer 2009) and auteur cinema. When interviewed, Varda often questions rather than confirms the labels that critics and spectators apply to her work. Martine Beugnet notes that Varda’s work denies ‘the divide between a subjective approach and her exploration of social issues’ (2004: 287). In other words, Varda’s subjective perspective cannot be separated from her interest ‘in depicting marginal subjects and in portraying disenfranchised areas of French society’ (2004: 288).

Betty Brandelli as she is being interviewed in front of Mortimer’s mural Brandelli’s Brig

O’Shaughnessy describes this attention to the margins as typical of a new wave of political film in French cinema.7 But Varda’s attention to the margins of society is truly remarkable because it runs through most of her films including her fiction works. Mona in Sans Toit ni Loi is probably the quintessential figure of marginality. The large number of analyses of this film show that scholars have deservedly paid attention to the themes of marginality and exclusion (see, for instance, Wild 1990, Rachlin 2006 and Déchery 2005). While it is discussed in Sans Toit ni Loi, this concern dates back much earlier in Varda’s career. As early as 1958 with L’Opéra Mouffe, Varda made a point of including images of homeless, drunk and marginal people.

Filmmakers invite their viewers either to discover new worlds and dimensions, or to revisit the world they think they know. Many of Varda’s films prompt a re-assessment of familiar spaces and figures. Giving the marginal centre stage and an active role in the film’s narrative is a recurring practice in Varda’s cinema. By using a selection of examples, I will demonstrate that Varda is a cinéaste passeur determined to capture images of those whom cinema often rejects. Varda’s method when depicting the margins requires specific attention. In fact, by analysing specific examples, one realises how Varda’s ethics of filming defines her praxis. The examples I will draw on belong to films shot at different times and in different places and these variants confirm that there is a strong constant running through Varda’s production.

In L’Opéra Mouffe, subtitled Carnets de notes d’une femme enceinte, Varda films among other things people chatting at the market and drinking at the local bar in Paris’s 5th Arrondissement. This subjective diary is full of associations and metaphors. The film, shot in black and white, runs approximately fifteen minutes and includes separate sections introduced by intertitles. L’Opéra Mouffe recalls silent cinema, because its sections are introduced by intertitles. At the same time, L’Opéra Mouffe does not try to mimic silent films since Varda uses a changing musical soundtrack throughout, rather than adopting a musical performance or a bonimenteur to accompany the film’s images. The film’s various sections do not all seem to be related to one another. One of them focuses on a couple named ‘les Amoureux’, another one, ‘Les angoisses’, relates the anxieties of a pregnant woman. The two most interesting sections through which to discuss the depiction of marginality are ‘Quelques autres’ and ‘l’Ivresse’. ‘Quelques autres’ is a selection of close ups on various faces, while ‘l’Ivresse’ shows the silhouettes of people sleeping on the pavement and inebriated individuals. The juxtaposition of these sequences with the more idyllic love scenes seems to illustrate the contradictory feelings and anxieties experienced by the pregnant woman of the title. As mentioned earlier, it is important to underline that Varda’s diary of a pregnant woman echoes her subjective experience: ‘L’Opéra Mouffe was a short film about the contradictions of pregnancy. I was pregnant at the time, told I should feel good, like a bird. But I looked around on the street where I filmed, and I saw people expecting babies who were poor, sick, and full of despair’ (Varda and Peary 1977).

Émilie cannot bear her friend’s questions and breaks down, alone and desperate

In another of Varda’s films centred on a woman’s experience, Documenteur, several fragments focus on homeless people sleeping rough in bus terminals, drinking coffee or wandering the city of Los Angeles. In the first part of this film, Émilie, the protagonist, spends most of her time trying to find a place for her son and herself after separating from her partner Tom. This process seems long and difficult although very few details are provided as to why. Until she finds a new place to live in, Émilie struggles with her new condition as much as with her overpowering emotions. She is, to borrow Varda’s words, ‘poor and full of despair’. During the film, Émilie’s frail figure is seen in a variety of public places, like a laundromat, a bar, a phone booth and a bus station. In all these places, people physically surround her, move around her, while Émilie is static, almost out of touch. The fact that Varda chooses to have her talking to very few people makes her isolation look even more intense. When Émilie is not filmed in a static and meditative position, the fact that she cannot seem to settle down illustrates the fluctuating character of her emotions, and the uncertainty that oppresses her. At some point, she bluntly tells her son Martin that until they find a ‘home’, they are disturbing their friends’ lives. This being literally ‘out of place’ is visually paralleled by the numerous shots of beggars and homeless people. Émilie is a double outsider who does not belong anywhere because she does not have a home, and because as a French person in California she does not seem to feel at home. This marginal status makes her akin to the many anonymous faces that the director films. This collection of close ups on homeless Angelenos reflects Émilie’s marginal position.

A rough-sleeper in Los Angeles, one of the many images of homelessness

This darker take on the city is a complex counterpart to the colourful and upbeat Mur, Murs. Documenteur revolves entirely around Émilie’s subjective experience. Her interior monologue is a crucial indicator of her estrangement and isolation. Her voice does not tell the spectator much about her material conditions, but describes her feelings in detail. While voluble about her emotions, Émilie says nothing of the marginal figures of California. The spectator cannot even say for sure if these sections are subjective shots. Does Émilie see these people around her, or is she oblivious because of her focus on finding a place to live? Do these shots belong to the narrative, or should they be assigned another status? They definitely do not fit easily in the diegesis. As none of these sequences are glossed over, they are left for the spectator to interpret. In fact, these sequences have three functions in the film. First, they illustrate what Émilie’s difficulties could lead to. Her new status as single mother makes it difficult for her to do everything, including work to make ends meet, find a new house, and a new school. Second, they give the spectator time to ponder Émilie’s monologue and to assimilate new information. And third, by inserting long takes focusing on these marginal people, which could be compared to what Noël Burch calls ‘pillow shots’ (1979: 162), Varda forces the spectator’s engagement to shift from the fictional to the documentary and in doing so, she points ‘offscreen to the embodied viewer’s concrete and intersubjective social world’ (Sobchack 2004: 284). So these passages do not only testify of the reality of Los Angeles in the 1980s, they also encourage us to engage with the bodies onscreen by evoking our own experience.

Varda’s focus on the margins of society is manifest in at least two other films for which she received critical and popular acclaim, Sans Toit ni Loi and Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse. Despite their differences, these two films share many traits. Both films gravitate around fragments of testimonies and stories. In Sans Toit ni Loi, Mona’s corpse triggers reactions and generates an a posteriori portrait based on the personal account of those who met her, and on the sections showing her before she dies. Sans Toit ni Loi is an impossible portrait in the sense that the locals have very different opinions on Mona. At the end of the film, there is no consensus on who Mona really was, and no consensus on what she wanted or on what drove her to life on the margins of society. In Sans Toi ni Loi, Varda does not provide any answer. She refuses closure and linearity in favour of fragmentation and indeterminacy. What she intended to make with Sans toi ni loi was an impossible portrait of Mona: ‘Vagabond is really constructed about different people looking at Mona – like building together an impossible portrait of Mona’ (Varda and Quart 1987: 6). The world she presents is full of people with certainties such as ‘les filles comme elles on les connait, toutes des allumeuses!’ (‘girls like her are all the same, she’s just another tease!’), but soon Mona’s existence and her mysterious death forces the people who criticised her to question their certainties. Eliciting the spectator’s participation is a common practice in Sans Toit ni Loi, as well as in Documenteur. The film contains many sequences similarly shifting from fiction to documentary. While long takes are certainly used to situate Mona within the landscape, they also give the spectator the opportunity to relate the film to his own embodied experience. Because of Mona’s silence and of the questions her death provokes, the spectator looks for clues in Mona’s body language as well as in the space surrounding her. He is compelled to consider the landscape in a more subjective way. This characteristic probably adds to the spectator’s impression that the narrative is fragmented and incomplete.

A real story inspired Varda when she started working on the project of Sans Toit ni Loi. Headlines depicting the death of homeless people because of particularly cold winter nights are not uncommon in France. This choice of a somewhat common subject coupled with the formal construction of the film is meant to hold the mirror up to Varda’s fellow citizens. When Varda chooses Mona as an evasive and missing protagonist, she makes her fellow citizens reconsider this apparently unremarkable event. For a film concerned with homelessness, Varda’s film is remarkable because it is neither didactic nor ‘donneur de leçons’. Rather, it is simply teaching the spectator to look beyond appearances and stereotypes at the bodily experiences of marginal individuals. It captures the coldness, hardships and solitude experienced by individuals who, like Mona, refuse to follow social conventions. Varda never romanticises Mona’s character, she is not an intellectual flâneuse, which is not to say that she does not reflect on her own choices in the film. Her character is presented in such a way that it is not easy to feel overwhelming empathy towards her. In the presence of other marginals, Mona can be puzzlingly as prejudiced or abusive as the so-called normal people of the film. On several occasions, Mona refuses the help of well-meaning people, with no clear reason to justify her attitude. Varda does not build up a black and white portrait, nor does she create a totalising narrative of marginality. Using a real story as a starting point, she invites the spectator to engage in a reconsideration of his certainties, just as she did when she started working on this film: ‘Around ‘84, the newspaper [sic.] were talking a lot about the new poor … The words new poor always made me think of the old poor, those who from time immemorial until today, beggars or not, have hung around the towns or roamed across the countryside’ (translated by and quoted in Smith 1998: 148).

Now, the last piece in this section concerns another film that undermines the idea of a single totalising narrative of the margins. In Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse, Varda undertakes an exploration of the idea of ‘gleaning’. Varda seems ‘as interested in creating fascinating fictive “vagabonds” as in exploring the ways in which her culture encodes and defines excluded insiders’ (Rosello 2001: 29). Her research on and exploration of gleaning takes her to various places where she interviews a variety of people whose complexities and contradictions she makes no attempt to conceal. Sometimes she follows people who look for food in the bins of supermarkets, while at other times she reflects on the legal meaning, or artistic renderings of the activity of gleaning. In this film, she accumulates and juxtaposes fragments that make Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse a subtle bricolage. Ruth Cruickshank associates the idea of bricolage with Varda’s film, because it is ‘part of a tissue of texts, made up of provisional differing and deferring meanings’ (2007: 127). Interestingly, Varda also describes her practice in Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse as a subtle bricolage mingling documentary interviews that are later edited into a fiction.8

Both these analyses of Sans Toit ni Loi and Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse show that in editing her collection of interviews, stories and testimonies, Varda becomes a cinéaste passeur who prompts the spectator to reconsider what is usually left out of mainstream cinema. The people filmed by Varda are for the most part neither young, nor beautiful. They do not form a coherent group, partly because the wide variety of reasons for their gleaning. Besides, Varda’s exploration of the term ‘gleaning’ is wide ranging. I would argue that this opening to possibilities is characteristic of her practice. Several critics including Cruickshank (2007: 124) and Rosello (2001: 33) have commented on a passage in Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse in which Varda forgets to turn off her small digital camera and films the dangling lens cap. In Mur, Murs, as mentioned, the sequence where she accidentally captures and incorporates the aftermath of a road collision into her film illustrates her acceptance of chance. So while Varda’s attention to the margins is related to Cooper’s description of the director´s ethic, which involves a privileging of others over the self (2006: 89), it is also important to note that her practice is always self-reflexive. In Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse, Varda never separates her observation of gleaners from her personal concerns about, for instance, the art of making films, or the ineluctable passing of time. They are weaved together in Varda’s subtle editing which establishes potentially meaningful connections for the viewer.

Notes

1 Varda’s poetics of space will be addressed in the following chapter.

2 The films are two separate entities but were made and released at the same time. Many consider them together including myself (Bénézet 2009: 85–100) and Michel Mesnil who calls the diptych Varda 81 (Bastide 1991: 108).

3 This particular film was shot during her first stay in America and dealt with the pivotal Free Huey rally held on February 17th, 1968, at Oakland Auditorium in Alameda, California.

4 For details on the power of images see Smith 1998: 12–59.

5 Some directors are fond of this practice, one can think for instance of Luc Dardenne’s Au Dos de nos Images, 1991–2005.

6 My translation of: ‘le travail du cinéma est avant tout de ressusciter pour chaque spectateur l’ici et maintenant de la rencontre filmée’ (Comolli 1997: 22).

7 For a detailed analysis of this phenomenon, see O’Shaughnessy’s The New Face of Political Cinema (2007).

8 ‘J’utilise la technique du documentaire pour refabriquer une fiction avec des interviews documentaires dedans. C’est un bricolage assez subtil qui me plait beaucoup.’ (‘I use various techniques of the documentary genre to fabricate a fictional account made of documentary interviews. I really enjoy making this subtle kind of bricolage.’) Part of Varda’s intervention during the Q&A section of the conference Le Cinéma et au delà at the university Rennes 2, recorded by Radio France and broadcast in April 2008.