‘Cinécrit par Agnès Varda’ is a caption that appears in many of her films and in an interview with Barbara Quart, she explains why for her this expression encapsulates the many possibilities of the cinematographic medium: ‘what I call in French cinécriture […] means cinematic writing. Specifically that. Not illustrating a screenplay, not adopting a novel, not getting the gags of a good play, not any of this. I have fought so much since I started, since La Pointe Courte, for something that comes from emotion, from visual emotion, sound emotion, feeling, and finding a shape for that, and a shape which has to do with cinema and nothing else’ (Quart and Varda 1987: 4). In this passage, Varda asserts the specificity of cinema and declares that it should be considered in its own right rather than conceived as a derivative or hybrid form of other artistic media like literature, painting and photography. Looking at this this quote, one also realises how much Varda has strived to maintain an exceptional position that she began with her first project in Sète.

Varda’s reluctance to follow pre-set production standards, and her desire to experiment with images and sound contribute to her originality. She has made commissioned films like O Saison O Châteaux (1957) and advertisements but she has also managed to remain independent thanks to the establishment of her production company Ciné-Tamaris in 1954. Other scholars have underlined Varda’s uniqueness historically (see Sellier 2008: 217), but what I want to examine here is the unorthodox quality of her cinécriture in order to see whether it matches her theoretical conception of cinema as ‘the movement of sensations’. To do so, I will survey a number of works and focus first on the unconventionality of her subjects and praxis to develop on to an examination of what Kate Ince calls her ‘carnal cinécriture’.1

In the introduction to her book on subjective cinema, Laura Rascaroli explains that one of the difficulties she faced when writing was to resist overtheorisation when discussing ‘the unorthodoxy of technical formats, of subject matter, of aesthetic values, of narrating structures and of practices of production and distribution’ of the essay films in her corpus (2009: 2). I would be reluctant to categorise Varda’s entire filmography as essayistic, but many of the issues mentioned in this quote are pertinent when thinking about her work. This is why this chapter will begin with a section establishing Varda’s unorthodox subjects and practices of production. To keep this chapter to a reasonable size, I will restrict my focus to four films that illustrate her unique praxis: Elsa la Rose, Uncle Yanco, Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse and its follow up Deux Ans Après.

1: Deceiving Expectations, or Why Unorthodox Subjects Matter

Elsa la Rose was originally conceived as a diptych on Elsa Triolet and Louis Aragon; two famous and charismatic authors who had been living and writing together for thirty eight years when Varda filmed them. Inspired by the principle behind Les oeuvres croisées d’Aragon et Elsa Triolet (a joint publication of their complete work started in 1964 and illustrated by artists including Matisse), Jacques Demy was supposed to make a film showing Triolet’s vision of her lover’s childhood while Varda was to create one presenting Aragon’s imaginary version of Elsa’s childhood in Russia. When Demy abandoned the project, Varda decided to carry on with her half but modified the project by shifting the focus from Elsa’s childhood to their recollection of the day they met and their relationship from then on. Elsa Triolet and Louis Aragon were well known in France as a very public, political couple. Aragon was a journalist, art critic and prolific novelist and poet who was involved in the French Resistance movement and the French Communist Party. He was also well travelled, having toured Europe with Nancy Cunard, a rich British heiress and former lover. Elsa grew up in Russia and lived in Tahiti with her first husband André Triolet before getting divorced. This stay triggered important life changes and when the writer and political activist Maxim Gorky read some of the letters she had written to Victor Schklovsky from Tahiti, he encouraged her to become a writer. She also lived in London and Berlin before moving to Paris in 1924. She translated Russian literature into French and was the first woman to be awarded the Prix Goncourt, a prestigious French literary award, for Le Premier accroc côute 200 francs in 1944. Aragon and Triolet regularly appeared on television together and Aragon often reminded journalists, critics and readers in his poems and interviews that Elsa, his muse, wife and intellectual partner had saved him from himself and enabled him to carry on writing.2 They met in 1928 at la Coupole in Montparnasse, a key meeting place for expatriates and intellectuals like Jean Cocteau, Man Ray, Josephine Baker, Simone de Beauvoir and Ernest Hemingway. It is also the café where Cléo listens to her song on a juke-box in Cléo de 5 à 7.

In Elsa la Rose, their meeting is re-enacted almost hypnotically with Elsa pushing the cafe’s swing door open in a fur coat and hat like the ones she was wearing on that day. Aragon acknowledges from the very beginning that his attempt to remember that day can only be tentative, and he tells the audience that even tiny details will never be able to match ‘l’infixable’ (what escapes him and what cannot be pinned down). Aragon has always been interested in playing with versions of his life on the page and in reinventing himself. He is a strong opponent to the fantasy of the origin, maybe because he was an illegitimate child who later as a writer would not let his absent father impose a name on him.3 Elsa la Rose is in a way a similar project of re-invention and re-creation with a pair of accomplices: Agnès and Elsa. Both women have a significant role in shaping the film. Triolet’s eloquent wit is obvious when she tells us what she remembers of the first time that she laid eyes on Aragon. His black suit ‘as shiny as a piano’ and his almost too good looks made her think he was a professional dancer (‘un danseur d’établissement’) rather than a writer or poet. In this film about memory and creation, Elsa will not let herself be relegated to a silent shadow over Aragon’s shoulder; she is much more than the mythical rose of the title. Both her voice and Varda’s voice take part in the polyphonic whirlwind of the film, which is also inflected by Michel Piccoli’s recitation of Aragon’s verse and Alain Ferrat’s song ‘Que serais-je sans toi?’ (composed in 1966 by Ferrat but based on Aragon’s poem).

Instead of making a classical biographical documentary, Varda embraces the idea of a documentary like a six hand piano composition which is complex and multi-layered. The film is not about Aragon’s work even if by the end of Elsa la Rose the spectator gets a sense of the content and style of his writing, and that in spite of Piccoli and Ferrat’s contrasting styles of delivery. Nor is it a fictional and rosy-looking opus on love and poetry. Many surrealists, including André Breton (a close friend of Aragon) idealised and glorified women, as if they were divinities. Many of Aragon’s love poems depict Elsa as beautiful and inspirational, but there are glimpses in the film of some of the material compromises that he had to make, like becoming a journalist to earn a decent wage after too many poor and bohème years in Montmartre. Aragon is clear about the fragile nature of love in ‘L’Amour qui n’est pas un mot’, a poem recited by Piccoli, when he writes: ‘c’est miracle que d’être ensemble’ (‘It is miraculous that we are together’). Love is fragile and precious but above all it is a collection of down to earth decisions and material events. When asked whether the poems that Louis has written for her make her feel loved, Elsa is unequivocal: they do not. It is daily life rather than poetry which makes her feel loved. The final section of the film is explicit when it comes to this utopian idea of love. Aragon’s voice tells us that we might see this film as a modern fairy tale, but it also reminds us that fairy tales are only malleable and ever changing fictions with artificial resolutions like ‘Ils se marièrent et vécurent longtemps heureux comme dans tous les contes’ (‘they got married and lived happily ever after, like in all fairy tales’). Aragon’s commentary at the end of the film is honest: this film is only one of the possible versions of Elsa, the lover he has imagined for the last thirty eight years, but this version is not representative of Elsa the imaginative creator of characters and fiction who has been working alongside him for all these years. If the film was turned over its head, as Aragon suggests at the end (‘Si, si… If, if…’), then he would probably become one of the minor characters of her books and as an audience we would experience something altogether different.

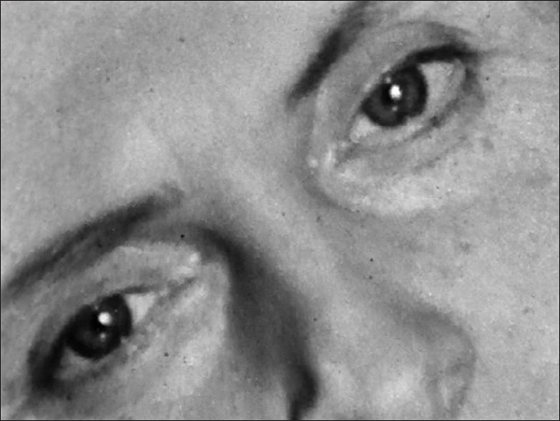

From the start, the whole enterprise is not about the pure knowledge of someone else, but about the exploration of multiple versions of a single event and about the passing of time. It is an essayistic piece shifting between fiction, documentary and aesthetic experiment. The re-enaction of the day they meet is, for instance, much more of a self-reflexive performance with a slightly comical twist than an attempt to recapture the past magic of that event. How many times can we see Elsa going through the swing door and Louis playing with a dice at the bar before it becomes clear that no representation can ever be truthful? Luck plays a part in their meeting, as Aragon mentions that they had missed each other in Berlin a few years earlier. The revolving door they go through several times, separately and then together becomes a symbol of time, chance and change. The mirrors and photos inside their home and Varda’s attempt to capture the vitality of Elsa with multiple close-ups of her face and eyes reinforce the idea that our true selves often remain a mystery to others. The fast-paced editing of a number of photos of Triolet shows that however close they are, Elsa remains a mystery even when Aragon asks her on camera what she is thinking about. Seeing Elsa and Louis’s gestures towards each other when together reveals their enduring affection. At the same time, misunderstandings are often played out. During an interview, he mocks the fashion sense of her sister’s lover, the famous futurist Vladimir Mayakovsky. She answers that the photo of him on the wall is out of date and that to her he looked like an extremely tall Jean-Paul Belmondo, handsome and impressive. Anecdotes are part of the narrative, but the film as a whole does not concentrate only on the personal. Many of the changes that affected the couple are correlated with important historical changes. The year 1933–34 associated at first by Aragon’s voice-over with the beginning of his career (and salary) as a journalist is connected visually with Berlin and the fire of the Reichstag. The long travelling sequence during one of his walks in sunny Paris with Elsa on his arm is in strong contrast with the short scenes that follow where violent demonstrations, Hitler and battles appear. Aragon was involved in politics and he was a supporter of communism and Stalinism, two movements which turned out to be a terrible deception for many intellectuals in France. Aragon’s passionate love for Elsa is juxtaposed with the cruel conflicts in Germany and Spain. The vertigo of love is the one the film concentrates on, but these short sections also justify some of his decisions and positions in the past, making sense a posteriori. Here, he is a passionate and immoderate individual both in love and politics.

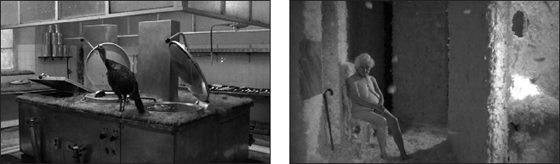

One of the many close-ups on Elsa’s face, here the focus is on her beautiful yet mysterious gaze

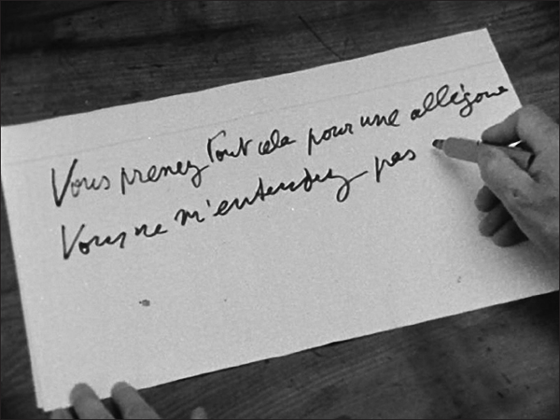

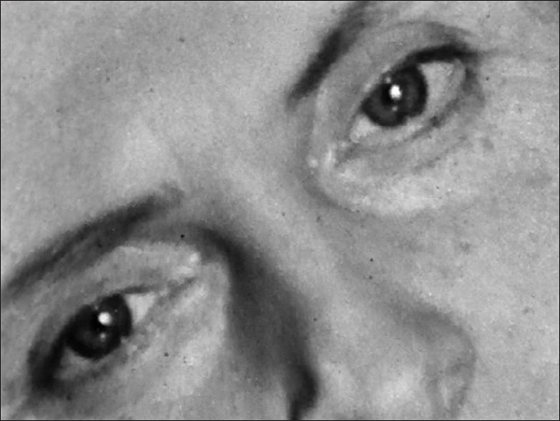

In Elsa la Rose, images and words are assembled in a vertiginous way to mimic the entangled layers of lived experience and one of the innovative and surprising choices in the film is the way it invites the audience to inflect the narrative. In the last long interview with Elsa in the garden, we are left to decide what to make of the shadow and presence behind her, of the handwritten captions ‘Vous prenez tout cela pour une allégorie, vous ne m’entendez pas’ (‘You think all this is an allegory, you don’t hear me’) and of the silent sequence that follows where we see Elsa and Louis chatting, smiling and simply enjoying time together. Piccoli’s hurried recitation does not help us, he is not a literary bonimenteur. The poems he reads add to the dense layers of images and ideas that we are exposed to. They do not clarify the images but intensify our attention, or if lost for sense make us cling to what we see as potentially more reliable. This continual exchange between the performers, creators, and audience is what makes Elsa la Rose unorthodox and impressive to this day. Refusing to freeze Elsa into a silent muse or to pin her down as the ultimate rose, Varda plays with Aragon’s text like she did in L’Opéra Mouffe with vertiginous cascades of free associations, between, for instance, a rose, an artichoke, a sea urchin and a gypsum rose. This film is not a classic biographic documentary since it incorporates contradictions and abounds in spontaneous digressions. It is a free spirited invocation by Aragon of ‘mon univers, Elsa, ma vie’ (‘my universe, Elsa, my life’), as well as a fragmented and poetic attempt to engage the audience through images, music and emotions.

Aragon’s handwriting interlude, or a trace of his inability to communicate with his interlocutors

2: Unorthodox Structures and Practices of Production

Uncle Yanco and Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse were made many years and many miles apart, but they both demonstrate Varda’s unusual and at times surprisingly spontaneous conception of filmmaking. Uncle Yanco is a twenty minute film shot over three days (October 27–30 1967) in Sausalito Bay before Varda has to fly back to France. She had heard about Jean (or Yanco) Varda from Tom Luddy whom she had met at the San Francisco Film Festival. Her reading of Henry Miller’s profile titled ‘Varda the Master-Builder’ had also made her curious to meet this potential relative.4 Yanco Varda was a painter and a teacher who lived with many others in a houseboat community full of strange and wonderful constructions. He is indeed a distant relative (since he is the cousin of her father Eugène) and one that Varda adopts very quickly by referring to him as ‘Uncle Yanco’ as if she was a kind of prodigal niece. Beyond these family ties, it is obvious that Yanco and Agnès share a mutual love of stories, colours and fantasy. The film is a joyful celebration of their reunion and experience together. Like La Pointe Courte, Uncle Yanco portrays a specific community, but in this film there is no Parisian counterpoint; the film gravitates around the central, patriarchal and hospitable figure of Yanco. He seems open to new encounters and glad to interact with people from all walks of life. He happily gives the director a nautical tour of the extraordinary houseboats near his own and invites her to a communal Sunday meal in his house. Varda is keen to leave traces of the making of the film like in Elsa La Rose. She re-plays with visible pleasure their first meeting in several languages and enjoys performing their first embrace behind various colourful filters in the shape of hearts. Here again there are multiples references to the place and time of the shooting, i.e. California at the height of the hippie movement, like the footage of demonstrations against the Vietnam war and love sit-ins. Hippie culture rejected materialism, competition, militarism in favour of communal love, illicit drug-induced ecstasy and non-Western philosophies and spiritualities (see Starr 1985: 238–41). San Francisco was in 1967 at the centre of this counter-cultural movement and the place where the ‘Summer of Love’ took place. In Uncle Yanco, the filmmaker decides, however, to refer to this movement obliquely. She is not filming sit-ins or demonstrations like in Black Panthers. It is when she films Yanco taking a big group of young people on his boat for a pleasure cruise, or when he walks around and stops to show her how this house is a place where love, music and art is made and discussed, that we clearly see how he belongs to that particular place and time.

Varda’s playful use of filters during the re-enactment of her family reunion in red (left) and an embrace with Yanco in yellow (right)

Yanco draws a family tree and establishes family connections for both Varda and the spectator

Many sections of the film are funny and irreverent, like when Yanco appears as a modern day Pythia behind a bright red window that a child opens every time he comes up with an unexpected prophetic prediction. Agnès and Yanco’s free-flowing dialogue seems to alternate between his musings on various subjects including art and politics and her questions that he either answers or laughs off. When she remarks that her father never talked of his family and had probably forgotten that he was Greek altogether, Yanco draws an ornate family tree for her. In a reciprocal movement, Varda inserts two shots of their daughters, establishing a continuity and parallel between their lines. Having elucidated their bloodline, they start to explore their imaginary lineage and Yanco explains that he can never be ‘un oncle d’Amérique’ (an expression in French which refers to a wealthy, distant relative who is willing to pay off your debts or help financially). Dressed up as a caricature of a cowboy, with a white hat, red tie and jacket, he looks like a comical version of himself especially since we have only seen him wearing bright pink and yellow clothes until now. Agnès and Yanco’s status as accomplices telling a story together is obvious when he shoos her off to have a nap, his sign ‘Do Not Disturb Siesta Time’ in full view. Even in the sequences where he is supposedly having a rest on his bed, he agrees to address her questions. During one of these conversations, he remarks that she should stop worrying about questions bigger than herself. His semi-cryptic answer using Cocteau’s opinion on life and death is to say the least personal: ‘La vie, la mort, c’est comme les catastrophes de chemin de fer, comme Cocteau a dit, ça ne s’explique pas, ça se sent’ (‘Life, death, like railway catastrophes, as Cocteau said, they can’t be explained, they can only be felt’).5 Yanco’s reference to Cocteau shows his rejection of over-intellectualism in favour of sensual experiences both in work and life, an interesting point when paralleled with what the film achieves. Varda’s colour filters and close ups on Yanco’s bright paintings, the patchwork of rock’n’roll and traditional Greek music, and Yanco’s oftentimes cryptic maxims are combined to produce a sunny documentary celebrating imaginary families, which is both unorthodox and radical.6

Yanco dressed up as a rich American uncle (left); Yanco in his usual attire (right)

While Uncle Yanco was made urgently as a personal tribute to her uncle, Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse is a more elaborate project/film in which time was obviously invested to offer an inclusive and dialogic result. Because this film was produced by her company Ciné-Tamaris, Varda was able to take her time and to take to the road on numerous occasions to meet people in different locations including the North of France, Beauce, Jura, Provence, Pyrénées Orientales and Paris and its suburbs. It is a truly peripatetic road movie if one looks at the regions it covers. Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse was very successful and received many critical awards. It is also notable for its popularity with an audience that did not know Varda’s work before seeing this film. One can assume that it benefited from the fact that at that time documentaries were making a ‘comeback’ in France and that a return to realism and to the political was also apparent (see Powrie 1999).7 The defining characteristic of new realism, identified as ‘an […] engagement with social realities, inhabiting an uneasy middle ground between the ethnographically dispassionate and the dramatically compassionate’ (Powrie 1999: 16) is evident in Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse. Varda’s interest in modern day gleaners testifies to her lingering interest in those considered by society as outsiders and misfits. In this film she seeks out ignored individuals to allow them to share their experience with those who are less in need. But there is another side to this project which offers a counterpoint to these images of suffering. For Tyrer, they form ‘the other side of the film’s structural dialectic, constituting a discourse of digressions […] moments in which Varda discovers ‘beauty’ in the lives and looks of marginaux […] in the heart-shaped potatoes that she gleans […] and of course in the various works of art that she encounters’ (2009: 170). As exemplified by this passage, Varda’s film also generated a number of scholarly publications, some interested in the politics of the project (see Tyrer 2009), others in different aspects such as the portrayal of old age (see Beugnet 2006, Rosello 2001). When Beugnet describes Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse as ‘a hybrid of essay, documentary proper, road movie and diary’ (2006: 4), she points to the difficulty one encounters when trying to categorise Varda’s work. In this section, I will restrict my focus to Varda’s unorthodox structuring of her film(s) and her constant consideration of the audience and participants since they are manifestations of her original cinécriture.

When Varda started shooting for this project in September 1999, very little was planned in advance and she spent eight months on and off the road to find gleaners willing to take part in this adventure. When asked about the making of the film, Varda recognises that luck played a huge role in the shooting schedule because she did not have a list of gleaners handy (see Varda and Meyer 2001). She asked her assistants and acquaintances to tell everyone they knew about her intended project and to contact any peasant, fruit grower, farmer or owner who might know some gleaners. Sometimes this quest almost turned into a detective story, where Varda would track a particular individual she had heard about like François, the defiant and charismatic gleaner who claims that he has managed without buying any food for years. Her scouting is also meticulous if scarily un-selective. When she drove, she would look for trailers and occasionally stop to ask people for someone who did not exist. She would carry on until this odd conversation starter would lead to an invitation to sit down and maybe have a drink or a coffee. She would then look around and explain that she was a documentarian and that she would like to chat with them for a little longer, and maybe even record them, either on that day with her little digital camera or at a later date with her team (see Varda and Anderson 2001: 24–7). Many people answered positively and these wide-ranging fragments of conversation ended up being part of the material she had at her disposal when she decided to edit the film into a coherent whole.

Some encounters led to unplanned scenes during the shooting of the film. In the beginning of the film, her interview with a group of potato farmers makes her realise that many end up dumping important amounts of perfectly edible potatoes, because they do not fit the commercial gauge, or were cut by machines during the sorting process. When these farmers tell her that people regularly follow their trucks to pick some of these discarded potatoes, she is no doubt hopeful and not ready for the letdown of reality: only one person is there on that day and he is there purely by chance. Ignoring her bad luck, Varda starts filming this man, suddenly interrupts him and enters the frame to grab a potato in the shape of a heart which will become for many the symbol of her film. She then proceeds to pick as many as she can and brings them back home to film them from up close, when abruptly, in one of her typical puns, she realises that these would be great for people going to ‘les restaurants du coeur’, a charity which provides meals for people in need. So she calls them up and tells them where the dumping site is for aesthetic and politic reasons so that they can collect hundreds of kilos of potatoes and she can film a group of people gleaning food together. As these volunteers (who are also beneficiaries) pick the potatoes, she asks them questions that will feed into the movie. This expedition would never have occurred had she not followed on a whim the tractors and trucks, and had she not stayed with the isolated gleaner who found her first heart-shaped potato. This chain of events makes visible how decisive time and chance are when Varda undertook this film. With a set schedule and detailed script, this could not have happened. For this lucky break to occur, one that also leads her to meet Claude M. (who lives all year round in a trailer with no electricity, and to whom she devotes a long sequence) Varda needs flexibility, openness and a fluidity in her approach. She is happy, for instance, to leave heavy material to film at home and scout with a small digital camera. Her willingness to abandon high-end film equipment in favour of low-end digital video is unusual since one could expect a filmmaker of her stature to be more selective or demanding. She justifies this decision in interviews by saying that the development of cheap and functional digital cameras prompted her to try them out in the hope that it would give her as much freedom as she had when she worked independently on projects like L’Opéra Mouffe: ‘The third reason which pushed me to begin and continue this film was the discovery of the digital camera. I picked the more sophisticated of the amateur models (the Sony DVCAM DSR 300). I had the feeling that this is the camera that would bring me back to the early short films I made in 1957 and 1958. I felt free at that time. With the new digital camera, I felt I could find myself, get involved as a filmmaker’ (Varda and Anderson 2001: 24).

After it was released, the film was so successful that Varda started receiving letters and presents as modest as potatoes shaped like hearts and as elaborate as artistic collages. A lot of people did not seem to mind her personal or aesthetic digressions in the final cut of the film (the diaristic and self-reflexive parts on aging and cinema) but felt compelled by them. It seemed that she had found a perfect balance between the objective and the subjective, two supposedly opposite tendencies of cinema that she tries to reconcile in many of her films: ‘Her inquisitive corporeal presence in front of and behind the camera endows her films with an aura of subjective honesty. Her conspicuous physical involvement in the image-seizing process evinces cognition beyond that of distracted and anaesthetized spectatorship’ (Chrostowska 2007: 130). This success led to the making of two corollary films: Deux Ans Après and Post-Filmum (2002) which need to be considered as they were made as a response to the audience of Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse and as a follow up to the experience of Varda and the participants.

Deux Ans Après was made two years after Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse but was not conceived as a money-making sequel meant to milk the success of the first film. Like Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse it proceeds by short bounds, by fragments, separated by intertitles. These sections can be watched chronologically but they can also be accessed from Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse by clicking on the blinking heart-shaped potato button located in the top right corner of the screen. This ingenious device gives the viewer the option to travel in time and space (unfortunately only forward) to see what has happened to some of the participants after the release of the film. In its introduction, Varda quickly glosses over the awards and prizes (‘ces machins’) that the film received and declares that she wants to acknowledge them in order to move on to more meaningful rewards: the letters and gifts. From the folder full of letters she received, she takes out a few and thanks everyone. She then selects an elaborate collage made with the paper case of a train ticket, and a cinema and tube ticket and asks: ‘Qui donc m’écrit dans un wagon?’ (‘Who’s writing to me from a train?’). In an instant, as if by magic, she is off with a train ticket of her own to meet the couple who wrote to her and capture their impressions in the flesh and on film. Reviving the tradition of the ciné-club (but on an intimate scale), a practice at its peak when she started making films, she meets Delphine and Philippe in Trentemoult, listens to them talk about their work as art workshop leaders, asks them questions about the film and spends the day with them. The filmed interview focuses on their dialogue, on their hands and smiling faces, on their hospitality and thoughtfulness. After this sequence, Varda returns home to more letters and tells us that many people were touched by the situation, and by the choices made by François F. She still sees him regularly, often offering him a coffee after he has gleaned at the market. In the interview that follows, she incorporates his dissonant and opinionated views. François does not sound bitter that his situation has not changed and he even seems genuinely surprised that more people have bought the Big Issue-type of magazine he sells at Montparnasse station, presumably recognising him. Varda explains that he was paid sporadically by theatre owners to come and talk with the audience at the end of screenings of Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse. What follows is an animated debate about the merits of the film between him, Varda (as she is filming) and a lady who was about to enter the station and caught their conversation. François liked the film but did not appreciate Varda’s self-reflexive vignettes and tells her that he found them unnecessary. The woman starts arguing with him and tells him that in her opinion Varda remains unobtrusive and a welcome addition which increased her pleasure when she rewatched the film recently. The discussion moves on to his activity as a volunteer literacy teacher and ends on a more peaceful note when the woman tells him that she is grateful for the opportunity to see people like him, who make her want to be better and to pay attention to others (‘Ça nous donne envie d’être meilleur, de faire attention aux autres’).

This section and those that follow repeat the modus operandi of Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse where Varda is gleaning impressions and experiences one after the other. In this second opus, she is still keen to present the work of artists like Macha Makeïeff and Michel Jeannès (Monsieur Bouton) but alternates these sequences with sections where she chats with some of the gleaners that she had filmed in Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse. In doing so, she accomplishes two unorthodox things. First, inspired by the effusive mail she received, she offers her spectators a paratext (or rather parafilm), an addenda that lets us see how these people are doing, how they have changed, and what they have experienced since the film has come out. Varda films Gislaine and Claude M. whom she had met in their trailers. Both still live precariously, and both still drink though according to them only occasionally. Gislaine says that she can go without a drink for five or six days; compared to her previous consumption of ten to fifteen bottles of rosé a day, this is an achievement. Like a shy schoolgirl, she also reveals that she has fallen in love and that if things are not perfect, they have nevertheless changed for the better since they last met. She feels better and more in control, rather than lost and powerless. The second unusual achievement of Deux Ans Après is the shape of the film itself, which becomes a contemporary cadavre exquis (exquisite corpse), a game created by the Surrealists. The principle of this game was to gradually collect images and words that would be assembled into an unexpected surreal whole. Through images, music and spoken words, Varda elaborates a rich and touching film, in which she incorporates her own experience of aging, grieving and sharing. When she follows François, who is running the Paris marathon with thousands of others, or when she films a demonstration against the Front National (an extreme right wing political party then led by Jean Marie Le Pen) ‘the movement of the film is decisively into the public arena’ (Corrigan 2011: 75). By reaching outward and by expanding on questions and issues evoked in the first film, Varda demonstrates her willingness to learn from others and to embrace chance while remaining true to herself, that is to say politically engaged and emotionally sensitive to the world and people surrounding her.

The DVD of Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse is a perfect example of Varda’s atypical conception of cinema, a conception open to new avenues and presented with humour. Besides Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse and Deux Ans Après, the DVD includes a set of additional boni full of surprises: a ‘Petit musée des Glaneuses’ (little museum of gleaners) which contains paintings and drawings often commented on, a section with legal texts about the practice of gleaning (from the Bible to the Napoleonic code), a short tribute to Zgougou, Varda’s cat who was given to her by Sabine Mamou, and a Post-Filmum or final instalment of the director’s ‘wandering road documentary’.8 The Post-Filmum piece subtitled: ‘Les derniers arrivages (un peu cassés), patate ultime-sublime et fin’ lasts less than a minute and could be interpreted as a conclusive audio-visual triptych. In a slow tracking shot to the right, Varda films the latest gifts that she was sent: (three gleaner motif plates, two of which are cracked) laid on a red tablecloth while we hear bird song including that of a nightingale. Is the use of these songs intended to suggest the renewal that spring brings about or to suggest through the date (July 2002) that we should enjoy summer for the few weeks that it lasts? This certainly depends on how optimistic the viewer is. A fade to black marks the transition to the final and sublime heart shaped potato (‘la patate ultime-sublime’), all dried up and shrivelled against a dark brown and earthy looking fabric. Finally Varda’s unmistakable voice proves one more time that she has a way with words as she gives us her version of ‘That’s all folks!’: ‘Cette fois-ci, c’est tout à fait fini!’ As in the rest of Varda’s project, this final instalment, which takes the shape of a pastoral, meditative still life does not provide definitive answers or solutions. Neither didactic nor utopian, Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse, Deux Ans Après and Post Filmum offer the audience an opportunity to witness a wide range of gleaning practices and raises political and aesthetic questions; it opens a dialogue between the people involved and the public sphere and expands outward encouraging us to reconsider the humanitarian and ecological issues it tackles like homelessness and overconsumption.

3: Varda’s Carnal Cinécriture

While the previous section focusing on Uncle Yanco and Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse intended to underline Varda’s unorthodox production practices, it also established the director’s desire to converse with the spectators of her films. To touch the spectators, Varda does not resort to easy processes of identification with charming protagonists, whose psychology is transparent and straightforward. She likes her characters to remain nebulous, independent and potentially surprising, and says so frequently.9 Mona in Sans Toit ni Loi and Viva in Lions Love (…and Lies) (1969) are perfect examples of characters who remain until the end of the films puzzling and obscure. Many of Varda’s protagonists, as Hayward remarks, defeat categories and stereotypes: ‘Mona assumes her filth just as she assumes her marginality, she answers to no one and thanks no one. In so doing she creates her own image and simultaneously destroys “the Image of Woman’’’ (1990: 271). So what does Varda do to make us react and to move us? What elements are key to her cinécriture? In ‘Soi et l’autre: Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse’, Claude Murcia explains that Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse inscribes the most marginal of the gleaners into an egalitarian and democratic patchwork which is valuable because of its diversity (2009: 44). She explains why reciprocity goes hand in hand with equality and comments on the importance of the bodies of participants as a means to make the other exist on screen: ‘Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse est un film qui fait exister l’autre. Dans son corps, dans sa parole, dans sa ‘vive voix’. […] Dans le film d’Agnès Varda, chaque protagoniste existe dans sa corporéité et dans sa singularité’ (Murcia 2009: 46). The corporeality and singularity of each participant is central to this project but it also resonates with other films by Varda. Corporeality is at the core of what I would call Varda’s cinema of interpellation. Like other forms of enunciational address, such as the direct gaze into the camera, an offscreen voice or intertitles, the bodies of the people on screen call our attention. Looking at the forms of address and the bodies calling for our attention in three very different films: Ydessa, les ours et etc., Réponses de Femmes and 7p., cuis., s. de b., … à saisir will help in defining Varda’s carnal cinécriture which I believe is based on an embodied vision of the world.

(A) Interpellation and ‘Conversation croisée’ in Ydessa, les ours et etc.

When Varda saw Ydessa Hendeles’s exhibition ‘Partners, The Teddy Bear Project’ in 2003 at the Haus der Kunst in Munich, she was taken aback by the scale of the project. Almost immediately she decided that she needed to meet the person behind the show, and to interview visitors to discover whether their reactions matched the intensity of hers. Varda’s curiosity and original shock thus compelled her to make the documentary Ydessa, les ours et etc I will argue that this initial reaction and the time she spent with Ydessa in Toronto are precisely what Varda, the director, wants us to experience. Through her editing of fragments of conversations with Ydessa and the visitors, and an embodied vision of the show, Varda proposes a perceptive visit and a reflection on art as a means to experience and understand the world.

Ydessa Hendeles was born in Germany in 1948, the only child of Jewish parents, both Holocaust survivors who emigrated to Canada when she was six. She is a passionate and charismatic Canadian collector, artist and curator who talks of her work in terms of ‘curatorial composition’ (Hendeles and Ferrando 2012). She is particularly sensitive to space and always thinks of a particular mise en scène for the objects she exhibits in her gallery and other museums.10 For that particular show, Ydessa had purchased and collected, over several years, hundreds of old photographs of people with a teddy bear and displayed them from floor to ceiling in two rooms whose atmosphere was reminiscent of a library or archive room. The visitors therefore started with documentary pieces: the photographs (generally grouped by affinities) and the display boxes with rare specimens of teddy bears. Each object contributes to the narrative that Hendeles is forging but it also holds a place in the composition as a whole. The visitor is free to watch the photos at her own pace, to ignore the ones that are either too high or too low, and the profusion of photos and saturation effect they create certainly encourages an intermittent attention. One thing that is set, however, is the order in which the visitor discovers the Teddy Bear Project. After the two rooms filled with photos, the visitor enters an empty room, in which the very realistic statue of a little boy, seen from behind, kneels in front of a bare wall, a work by Maurizio Cattelan called ‘Him’. It is then a great shock to find that the little boy’s face once you get to see it is that of Adolf Hitler. Now, the visitor must turn back and look at all he has just seen with new eyes. The teddy bear, a symbol of comfort and protection, has lost its innocence and the visitor must now reconsider the reasons behind the grouping of certain photos, the significance of juxtapositions, and the logic driving this exhibition, set in a museum opened in 1937 and built to Hitler’s orders to exhibit Nazi-sanctioned art.

A general view of Partners in Munich with the vertiginous display of photos and the bears (left); the sculpture in the final room of the exhibition (right)

Varda’s film, like Ydessa’s exhibition, defers this final revelation and only discloses the content of the last room in the second half of the film. Until then Varda alternates between scenes and interviews in the first two rooms, conversations with Ydessa about her approach, still close ups of photos selected from the show, and mobile shots gliding over the photographs on display that suggest movement and mobility. The visit to Ydessa’s exhibition we are invited to join in Ydessa, les ours et etc is based on the director’s subjective recollection, it is a reconstruction of Varda’s impressions after the fact but based on clips and close ups. Varda and Ydessa’s sensibilities collide in the space of the gallery and in the film, and their ongoing conversation offers the spectator an opportunity to think about the idea of indirect or inherited memory. For Ydessa, the concept of inherited memory and family heirloom are particularly meaningful. Like many descendants of emigrant or deported Jews, Ydessa owns only one photo that pre-dates World War II (that of her grandmother) and she says that she misses this sense of visual roots and all the mythology that goes with family albums. On screen, she stresses the fact that she is not a survivor, but she states that she has inherited her parents’ and grandparents’ history. She cannot escape this legacy and her identity is bound for ever to her family’s displacement and later immigration to North America. Like the visitors at the end of their journey trapped in the white room, she is defined by her past. The fact that the only photographs with a caption in these two rooms are those of Ydessa with a teddy bear and her parents identified as Holocaust survivors might have alerted some of the final shock to come, but this could also have simply been a way to point to the origin of the collection.

Varda’s experience of World War II is different from Ydessa’s. Her family emigrated from Belgium to Sète during the war, and when questioned about that period of her life she claims that she was unaware of what was happening, too young to even understand the activities of the resistance. Varda started working with Jean Vilar in Avignon in 1948 at the age of twenty, and trained previous to that as a photographer in Paris. So during these years (before she moved to rue Daguerre in 1951), Paris, a city still feeling the impact of the war and occupation, must have been an eerie experience for a young woman used to the quiet village of Sète. In her films, many Parisian characters (like Cléo or the pregnant woman of L’Opéra Mouffe) feel overwhelmed by the big city. The only war evoked in Varda’s filmography though is that taking place in Algeria. In 2007 the French government asked her to conceive an installation commemorating in the Panthéon ‘Les Justes’, those French citizens who risked their lives to save Jewish people (often children) during the war. Ydessa, les ours et etc and this installation are therefore her only frontal confrontations with experiences and memories of war. Regardless of her personal circumstances or professional choices, Varda understands the haunting quality of World War II’s emotional trauma if only because as someone who lived and worked in France at the time, her life became inextricably entangled with the legacy of the war and the memory of those who died.

Thomas Weski, the curator of the Haus der Kunst, speculates about Ydessa’s initial motivation when collecting personal photos, and suspects that she was trying to compensate for her lack of personal mementos. Varda sounds less naïve underlining the fact that Ydessa has gone well beyond fashioning a fictional substitute. Rather, she sees Ydessa’s photos as a giant panorama so rich and diverse that any visitor will be able to engage personally on one level or another with Ydessa’s collection. A German visitor echoes her view when she says that she feels that the artist has assembled a monument to humanity’s collective memory, and indeed how could we not see any links between ourselves and these figures of the past? But this fantasy of ourselves as sharing the same collective memory is allegedly hit hard by the last room’s content. Forced to face the deeds of our recent history through such a potent figure, what will be our reaction? How will we turn back and face all these images again? What will this unexpected figure trigger? The visitors that we hear immediately after this revelation express disarray, discomfort and malaise. Varda illustrates this feeling of physical and mental oppression by superimposing their faces with that of the statue, which becomes an unforgettable and daunting shadow regardless of the nationality of the interviewees (French, German or American).

Varda trained as a photographer and she has never lost her eye for still images and composition. As her recent exhibitions show, she has not completely abandoned photography either, but continues to experiment with movement and stillness within and around the frame.11 Ydessa is fascinated by the potential of photos, not just as works of art but as triggers and as meaningful artefacts of a time which is now past. Her meticulous attention to assembling a series of photos is no doubt similar to that of Varda who worked on projects where still images gave rise to animated and moving sequences like in Salut Les Cubains! (1963) or Ulysse (1982). In the first conversation filmed between Ydessa and Varda, Ydessa is clear, she thinks of meaning and narrative when acquiring objects and artworks: ‘What meaning can I pull out when I work with the objects that I choose […] to make articulate visual contemporary art statements?’ Like Varda then, she is a provocative story-teller and an animator of objects. She wants her gallery (or the museum she exhibits in) to become a space infused with discursive and emotive potential. Like Varda who constantly thinks of her spectators, she wants to trigger reactions, questions and debates. The provocative figure of Hitler is one means to get the visitors to react and engage with the material that they have viewed. To trigger reactions, Ydessa tries to build bridges between the visitor’s mind and the works that she curates, between their bodies in the gallery and the space itself (as well as its history if there is a special one attached to it), between the past and the present. Varda and Ydessa are both ‘passeuses’ and ‘enchanteuses’ although I would argue that the tone of their works often differs. Ydessa is outspoken and determined when she presents what she does to Varda: ‘My show deludes them [the visitors]: I create a fantasy world where everyone is happy, where everyone feels secured and has a teddy bear.’ When she deludes her audience, Ydessa does what storytellers do whatever medium they work in. She takes various elements, assembles them in a particular, sometimes beautiful, sometimes challenging way to entice the viewer to look at reality differently, to affect them and move them.

In Ydessa, les ours et etc. Varda takes the role of a bonimenteur. She lets Ydessa speak but she also frames her, editing sequences carefully and modifies ‘Partners’ to engage the audience via purely cinematographic means. After a suspenseful journey to track down Ydessa, the mysterious ‘woman with a name fit for a novel’, she films a striking (and at first silent) slim, black figure against the white walls of her gallery in Toronto. Varda selects a series of photos from the show and time and again suggests narratives: ‘Once upon a time, there was a brother and a sister’; ‘in grammar school, all the boys were in love with their teacher’; or asks questions: ‘like Jules and Jim maybe, who knows?’ Varda even inserts herself in the Teddy Bear project by adding a photograph of herself as a child in a series of photos of little girls wearing bows in their hair. But she is quick to point out that she never owned a teddy bear and that this is a fantasy of hers, a mise en abyme. While she takes into account the reactions of various visitors, she also imposes her narrative and experience on the film.

Varda does not only encourage the spectator to listen to her stories, she also wants her to feel things alongside her by using fluid camera movements and close ups in and out of the exhibition that recreate her own sensations. To illustrate this point I will turn to two scenes which significantly frame the film. In the beginning of Ydessa, les ours et etc., just after the credits, the camera takes us on a short un-narrated tour of the first two rooms of the exhibition. Isabelle Olivier’s atmospheric harp music perfectly matches the slow and fluid movements of the camera, mimicking the gaze of a visitor which finally comes to rest on a display case containing a big, inoffensive looking teddy bear, sat on a chair under a light, a vignette that seems to say: ‘lights – camera – action!’ This brief sensory-rich respite allows us to experience for ourselves what Ydessa’s show feels like, right at the beginning of the film. In the rest of the film, Varda intends her voice and commentary to be both a guide and a reference, but here she voluntarily leaves us for a moment to invest this particular situation on our own terms. In the other scene, at the end of the film, we are in Ydessa’s house while she works on a book based on her exhibition. Varda films Ydessa’s busy activity in her huge kitchen and the dozens of photos lined up on the floor, and suddenly she becomes disoriented and dizzy. Like Alice in Wonderland who cannot find her bearings once she has stepped out of her familiar environment, Varda feels lost in front of this vertiginous project possessed by Ydessa’s obsessive energy and her haunting exhibition. A series of high angle shots of Ydessa ordering her images over the geometric tiles of her kitchen and under lines of hanging kitchen utensils looks increasingly bizarre, like a sketch by Escher. The numerous shots at odd angles and the crescendo pace of editing refuse us any clarity until an increasingly unsteady and fast moving camera glides over the path of the images assembled on the floor, finally taking us to a similar series of straight lines, this time on the ceiling of the Haus der Kunst. Olivier’s harp provides a sound bridge to the space of The Teddy Bear Project, its melody synchronised with the unsteady camera, thus evoking Varda’s final word ‘vertige’ (vertigo). When the camera eventually stops moving, this feeling of vertigo has not completely receded because the low lamps placed over the display cases and photos are still swinging in mad circles, forming a surreal ballet of luminous pendulums. The reference to Alice in Wonderland is certainly intentional on the part of Varda who has just presented to us another aspect of Ydessa’s personal art collection full of oversized and tiny objects scattered around the massive mansion that she occupies by herself. The return to the walls of the gallery may bring the camera to a halt, but this stasis will not give us easy answers or any sense of a resolution. In this dreamlike and vertiginous sequence, built on masterfully edited sensory images and music, Varda reframes Ydessa’s project and makes us experience her emotions as well as some of those expressed earlier by the visitors to the exhibition. This revisiting of her impressions combined with an appeal to our senses shows how Varda’s films depend on a carnal cinécriture based on an embodied vision and on a network of corporeal images (‘des images qui naissent dans le corps’) (Varda quoted in Bastide 2009: 18) that need to be elucidated.

In this documentary, we are called to take part in a sensory ‘conversation croisée’ (or double dialogue) where Varda and Ydessa are partners and directors of their own work. Both try to guide the viewer and both are interested in provoking and shocking her with unusual assemblages of images that will affect her physically. Soliciting the spectator via movement and stasis around the images, informing us how we see, or temporarily ignore what we see is part of their common objective. How could we not notice the guns and weapons held by the children, the soldiers, and the sports team reminiscent of those who filled the ranks of the army and the ghettoes? Varda has the final cut of Ydessa, les ours et etc. so it might be hard to see this documentary as a collaboration between equal partners, but it is definitely a striking and provocative conversation, a moving reconstruction and an invitation to let complex works of art affect us intellectually and physically. Via this sensory exploration of different times and spaces, Varda endeavours to connect us with a history that may not be our own, to touch us and to encourage us to re-think our engagement with art and its multiple narratives. In the end, we may not be sure about what to answer when asked at the end of the film ‘Qui regarde qui?’ (‘Who is looking at who?’) but we have learnt that we can and should all engage productively and creatively with the mystery of the still and moving images surrounding us both inside and outside of the gallery.

(B) Manifesto, Interpellation and Action in Réponses de Femmes

In 1968, a group of French film directors including Chris Marker, Alain Resnais and Jean-Luc Godard decided to take revolutionary action by making short black and white silent films that would be numbered and anonymous yet highly personal (each director was to self-produce and self-edit). Those short films were militant in their message and distributed outside of the commercial circuit to like-minded audiences. Many were filmed during the demonstrations and events of May 1968 and most opposed the vitality of young militants to the old conservative bourgeois order epitomised by De Gaulle’s government. They were conceived as an alternative form of news, a new form of agit-prop and an encouragement to this momentum of change. Varda was not in France in May 1968 so she did not contribute to this corpus. She may have been friends with Marker and Resnais but as mentioned earlier she was a bit of an outsider and her prior involvement in a group project (with Loin du Vietnam) did not amount to much.12

So what is exactly Réponses de Femmes which is described in the credits as ‘un cinétract d’Agnès Varda’? This eight minute film was made for Antenne 2, a French television channel, to celebrate women since the United Nations had decided that 1975 would be International Women’s Year. Its description as a cinétract is deceiving since, however militant, it is produced well after the canonical corpus of French cinétracts. Réponses de Femmes is therefore an unorthodox cinétract both in its form and in its content. Formally it deviates from the 1968 corpus since it is shot in colour, relies heavily on the participants’ voices, identifies categorically Varda as its author and is made for television.13 In terms of content, it is also different for two reasons: first it focuses on the experience of women in the mid-1970s (and does not focus on 1968 as a foundational date), and second, it is blunt and provocative in its approach to the body, women’s rights and female experience. In the 1970s, activists had won important battles like the legalisation of birth control in 1967 and the de-criminalisation of abortion in January 1975 but many feminists thought the conditions and rights of women in France could still improve. At the time, Varda was involved in the feminist movement and signed in 1971 the famous ‘manifeste des 343’, one of the texts that generated outrage but initiated debates and changes in the legal system. It is therefore important to underline that feminism constituted a pervading topic during this decade and a personal preoccupation for Varda.

The instigators of the television series ‘F comme femme’ had asked Varda and several other women including lawyers, historians, sociologists, and filmmakers: Qu’est ce qu’être une femme? What does it mean to be a woman? Very quickly Varda decided that she wanted to make a pragmatic rather than theoretical film about ‘Notre corps, notre sexe’ (‘our body our sex’). To drive the point home, Varda filmed a variety of women, often but not always naked, an element that some found excessive.14 In this cinétract, there are many naked bodies, some young (including an infant) and some old but, like Orpen I would not call any of these nudes ‘titillating’ (2007: 71). The women we see are staged and often posing for the camera in elaborate compositions. When they move, which is rare, the blank space of the studio behind them, the recurring intertitles and their gaze at the camera make it impossible for the viewer to ignore that their bodies convey a message. What in retrospect seems more shocking to film and feminist studies specialists today is the essentialist view that Varda seems to endorse. Kate Ince pinpoints this when she writes: ‘For the majority of critics writing in the 1970s and 1980s, the very notion of a “feminism of the body” was biologically essentialist, and rendered problematic Varda’s evidently positive pleasure […] in representing the gestating or artistic female body’ (2012: 13). The opening question in Réponses de Femmes and its immediate answer: ‘Qu’est ce qu’être une femme? C’est naître dans un corps de femme’ (‘What does it mean to be a woman? It is to be born in a woman’s body’) seems to be in direct opposition with De Beauvoir’s influential phrase: ‘On ne naît pas femme, on le devient’ (‘One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman’) in The Second Sex. I would argue, however, that the questions evoked through the body in this very short film such as ‘Do all women want to become mothers?’ are timely and discerning. These questions address and challenge the ways in which the female body is perceived, represented and treated by society and the media. The bodies on screen force spectators to question their views and their position in society: are we objectifying women on a day to day basis? Are they oppressed by stereotypes and if so how? When do we, as a society, start imposing reductive and retrograde clichés on children, and is formal education an accomplice? Are legal changes adding challenges for women by separating reproduction and sexuality? Why is it that people react so strongly to the naked bodies of pregnant or older women? And are things really changing in the public arena? In this film, Varda is not ignoring Simone de Beauvoir’s work but she wants to remind the viewers that the female body has never been and will never be neutral: it carries certain values, it is taught by various discourses and gestures how to behave, it is managed and controlled.15 One of the crucial questions to consider is whether the female body can be set free, and if so, by whom? Varda does not present women in the 1970s as free, liberated and unhindered by society; the women she films are able to speak out but like the little girl who is heard repeating the same sentence twice, they can only hope that ‘Maintenant ça va changer!’ (‘From now on, that’s all going to change!’).

The cast of Réponses de Femmes includes a wide variety of participants: some young, some old, some naked and some dressed

Having established the feminist bias of this cinétract, one also needs to consider how it compares with other representations of the female body on screen. Antoine De Baecque summarises in his essay ‘Écrans’ (2006) how the cinematographic representation of the body has changed over time. Determining where Varda’s film is situated on a historical continuum is an important question. In its early years, cinema represented bodies as spectacles and as sources of burlesque entertainment as in the films of Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd. Then Hollywood started to create, control and promote a glamorous type of body through the figure of the femme fatale and its many incarnations on screen. It is later in the 1960s that modern cinema broke away with earlier and more traditional visions of the body. This modern body is different from its earlier sugar-coated and tamed versions. This unruly and liberated body becomes for new wave filmmakers and others a means to denounce the pseudo-realism of films made in studios. Réponses de Femmes is a fine example of modern cinema in that it presents women of all sizes and ages: the slow and silent tracking shot that gives us a chance to watch the participating women’s faces (each ‘tête de femme’) and the vox-pop section at the end of the film add to this impression of variety and uniqueness. At the same time, the film experiments with its own ‘artiness’ and draws attention to its construction with the sound of the clap and lingering presence of a technician in the frame. The particular style of delivery of the non-professional participants and the film’s carefully scripted dialogue also points to Varda’s careful mise en scène and mise en texte (script-writing). All these traces and markers tell us that we are watching a carefully crafted and polemical film, one that tosses ideas around and expects the audience to respond one way or another.

To interpellate the viewer, Varda does not only rely on bodies, she also experiments with the voices of the participants who repeatedly tease the audience as well as their interlocutors on screen: a fairly large and silent group of men identified at the end as ‘Messieux les pères, les amants, les maris, les patrons, les mecs et les copains’ (‘dear fathers, lovers, husbands, bosses and buddies’). In the film, individual or choral delivery of statements like: ‘Je ne suis pas limitée aux points chauds du désir des hommes!’ (‘I am more than the hot points of men’s desire!’) or ‘Qu’est ce qu’un corps de femme si on doit toujours rendre compte de nos poids et mesure?!’ (‘What is a woman’s body if we must always account for our weights and measures?’) alternates with several off-screen voices, including that of Varda and an unidentified man. This man plays the role of the devil’s advocate and has a hard time coping with the consequences of the feminist revolution of the 1970s: ‘Continue comme ça! Plains toi! Bientôt tu cesseras de nous plaire!’ (‘Go on, keep complaining! Soon we’ll no longer desire you!’). His reluctance to change does not bode well for the future, but in a last minute poetic twist Varda concludes on a more hopeful note. At the end of the film, she edits an unusual face-off between the group of men and the group of women, all dressed now, who having complained about their objectification declare that things need to change. The most radical of them then says ‘je suis une femme, il faut réinventer la femme’ (‘I am a woman, women must be reinvented’), and the male off-screen narrator answers ‘Alors il faut réinventer l’amour’ (‘Then love must be reinvented’). To this peculiar reworking of Rimbaud who claimed that love must be reinvented, the women answer in unison ‘D’accord’ (‘Agreed’).16 By shifting the focus onto the ideological travesty of love, the director implicates society as a whole and suggests that joint responsibilities must be taken for significant changes to happen. Réponses de Femmes is split in terms of space between the perfect space of the studio and the chaotic building site behind the silent men. For things to change, the political ideals of women need to be debated by society as a whole including men. It is only through these animated discussions that a balance will be reached in the public sphere, away from the messiness of the building site and the all-too-perfect studio. This debate and issues are therefore a work in progress and as Varda concludes: ‘À suivre donc’ (‘To be continued’).

(C) Sensations and Emotions in 7p., cuis., s. de b., … à saisir

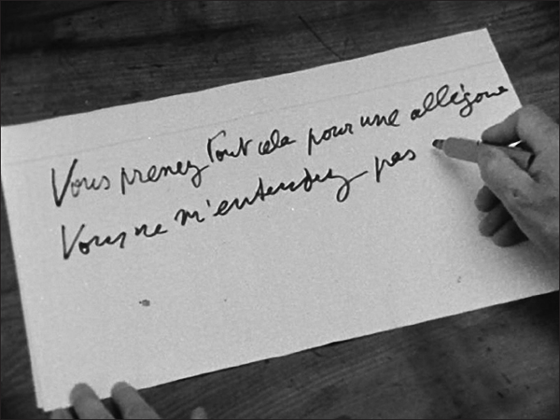

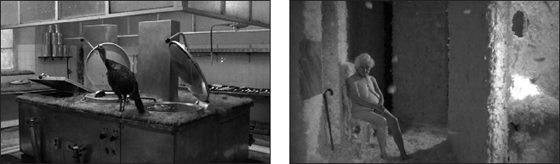

The last film I want to discuss is like, Ydessa, les ours et etc., a film that came about as a reaction to an exhibition. In 1984, in the building of Hospice St Louis in Avignon, Louis Bec was given free rein to set up an exhibition that he called ‘Le vivant et l’artificiel’. Varda, remembering her reaction to the show, says that she was mesmerised: ‘Un désir immédiat en découvrant l’exposition Le vivant et l’artificiel qu’avait organisée Louis Bec à Avignon et dont je me suis servie tout autant comme prétexte que comme motif, matière et décor. J’ai filmé comme on rêvasse’ (‘I was seized by a sudden desire when I visited Louis Bec’s exhibition in Avignon ‘The Living and Artificial Life’ and used it as an excuse, a motif, a set of material and a film-set. I filmed it as if I was daydreaming’) (Piguet and Varda 2007). Bec and his collaborators (Danièle Sanchez and Hervé Mangani among others) had made a unique use of space and brought unexpected elements into this former hospice including stuffed bears in the corridors, live lamas in the courtyard and turkeys in the kitchen. Anatomical wax models from the collection of the self-proclaimed doctor Pierre Spitzner which toured the fairgrounds of France and Belgium in the 1920s and 1930s were also displayed in various rooms, including his famous sleeping Venus. Inspired by her original experience and gut reaction, Varda makes a puzzling film which uses both this exhibition and the space of the hospice as starting points for an experimental rêverie.

Summarising 7p., cuis., s. de b., … à saisir is a challenging task even if the obvious common denominator between the sections of the film is the building of the title which is at first described in terms of an excellent real estate opportunity (‘à saisir’ is the explicit subtitle of the film). The offscreen voice of an estate agent talking about this house and its previous owners, a doctor and his wife, are the first elements we learn about, as a staircase and massive closed doors welcome us. The rest of the film will see many doors opening on a variety of vignettes, some narrated by the estate agent we never see, or by former occupants of the hospice, while some are performed by a family and their servant at different times of their life. The film is also punctuated by mysterious short tableaux which do not necessarily relate to the family plot but which evoke emotions associated with the building’s various rooms. Based on the idea that these walls have a soul (‘ces lieux ont une âme’) and that in empty rooms, you can write your future but also get a sense of the past, Varda experiments with layering a number of vignettes through which we learn about the frustrations, love stories and daily life of the family and former occupants. In two separate episodes which I call ‘conversations in bed’, the doctor and his wife discuss what their life as young passionate parents feels like, and later how distant from each other and unsatisfied with their lives they have grown over the course of a decade. Scenes about their family life and brood of children are played by a mix of actors, non-professional participants, and wax figures. Yolande Moreau plays the last of the family’s maids, while earlier servants are shown as a couple of wax figures presumably killed by syphilis or a disfiguring disease. Louis Bec assumes the role of the older doctor and is, I suspect, also the narrating estate agent. As a whole, the film is an unusual and provocative piece which I would describe as a kind of hallucinatory rêverie.

What I find of particular interest in relation to the rest of Varda’s production and the notion of carnal cinécriture is the experimental layering of emotions and sensations that the director uses not only to tell an elusive set of stories, but to shock the spectator into reflection. In 7p., cuis., s. de b., … à saisir emotions indeed run high since the family goes fairly quickly from an idyllic unit to conflict and havoc, with at the centre of the dispute a rebellious young girl Louise (who has just turned eighteen) and her father Louis who is both authoritarian and uncompromising. Louise wants a job rather than family (‘ce qu’il me faut c’est un métier et pas de famille’), and as she looks out the window she imagines the other life that is waiting for her outside (‘Derrière ces platanes, il y a la vraie vie’). On the opposite end is her father, a former epicurean who has become a self-centred and conservative patriarchal figure who cannot bear the thought of his children being independent and autonomous outside of his control. The mother, although not inarticulate, does not seem particularly supportive of her children, partly because she too feels trapped in a life that she did not want.

This conflicting set of emotions is not easy to navigate because the vignettes are short and often cryptic. Like Spitzner’s sleeping Venus, the mother looks calmly alive but there is no way for the spectator to know what emotions are at play inside her. Spitzner’s wax model had a mechanical movement intended to emulate breath so that her chest rose and fell as she lay on a bed in her white nightgown. Like many other anatomical waxworks, her body could be opened to reveal her organs to the scrutinising gaze of doctors-in-training or the audience of a fair. The comparison between the mother and this model (which straddles life and death in sleep) is all the more eerie because the audience knows that what leads to the sale of the property is a tragedy involving the mother which compelled the husband to leave the house with all his children. In the film, the mother remains an unresolved character, repeatedly associated with other wax figures including one of a woman having a Caesarean and delivering twins. Her indecipherability shows that individuals remain a mystery despite a detailed knowledge of their anatomy, reproductive organs or brain functions. They may express some of their emotions through dialogue, but they remain largely unknowable. Some of the most inventive lines in 7p., cuis., s. de b., … à saisir confirm this point, for instance, when the doctor tells a younger colleague: ‘Je répète à l’envie un texte de systémique zoologicienne en conjugant des activités fabricatrices, déclamatoires, symboliques, fantasmatiques, gesticulatoires, testiculatoires, avec des activités logiques, rationnelles et axiomatiques’ (‘I’m doing a zoologistical sytemic that conjugates fabricatory, declamatory, symbolic, fantasmatic, testiculatoric acts with logical, axiomatable acts’).

Spitzner’s Sleeping Venus, an eerie wax model used in Varda’s film

Besides the classic love/anger dynamic between the father and his daughter, and within the family more generally, there are a number of other emotions evoked in 7p., cuis., s. de b., … à saisir Sadness and resignation are expressed through other participants, such as the former residents of the hospice. Elderly people and former residents haunt the space of the house at regular intervals. Even if they left the premises years ago and belong to a fairly distant past, their presence and their voices remind the audience that this building is a receptacle for layers of different past experiences. In the beginning of the film, by their mere presence a group of old people make us question the imaginary harmony usually maintained between the soundtrack and the images. Sitting on chairs set up against the walls, they are all neatly dressed and silent in what could be the waiting room of a doctor’s practice, but at the same time the slow tracking left on an elaborate display of white sculpted heads in the centre of the room, and Barbaud’s violin make the scene both mysterious and uncanny. Some of these elderly people also appear unexpectedly in empty rooms, stating their attachment to the house they had to leave (‘je ne voulais pas quitter cette maison’). They are either standing in the distance, as two tiny lines at the end of a long room, or their face appears over the walls while we hear their off screen voice. The short testimony of a previous occupant adds to the dizzying quality of the emotions that the audience is exposed to. She remembers the light filtering through the plane trees behind the windows and what it felt like to live in this space. Her careful diction and nervous tics make her effort to describe her memories all the more poignant. As an image and an incarnated voice, she is a striking but also fleeting repository of past memories. This array of mysterious and haunting emotions summoned by the house contributes to the hallucinatory nature of 7p., cuis., s. de b., … à saisir They also complement the sensory triggers that Varda uses on numerous occasions and which need to be discussed to address the carnality of her cinécriture.

While many of the situations at hand in 7p., cuis., s. de b., … à saisir necessitate an intellectual effort from the spectator, some only require an openness to the immediacy of images and sound. The emphasis on the senses in certain scenes illustrates the incarnate character of Varda’s cinematographic vision. Sometimes she creates unexpected juxtapositions and transforms the space of the former hospice into a magical and eerie place. The kitchen empty and, as the estate agent claims, full of potential is turned into a wild garden, with grass on the hob, bright blue jelly and gurgling water in its pots and pans, and live turkeys gobbling and walking free. The collective bathrooms are transformed from austere whiteness to a plush Eden, where Adam is an infant lying in a tub full of feathers and Eve an old naked woman who is enjoying a shower of feathers before looking at us from a chair. In these extreme yet familiar places, Varda gives prominence to the corporeal dimension of cinema. She reinvents the standardised language of cinema, which usually ‘appeals more to narrative identification than to bodily identification’ (Marks 2000: 171). Sometimes she favours a less bold and more humorous evocation of sensations. In a memorable scene served by Moreau’s wonderful acting, Varda jumps from sensation to word play to performance. In the green kitchen, the maid played by Moreau breaks eggs relentlessly and recites adages like ‘Y’a pas d’omelette sans casser des oeufs’ (‘you cannot make an omelette without breaking some eggs’) as if in a trance. At the end of the sequence, she spits in the container in front of her, explaining that ‘Monsieur les aime bien baveuses!’ (‘The boss likes him omelettes runny’, baveuse literally meaning dribbling in French). This conclusion echoes the rebelliousness of Louise, who seems to consider Yolande as an ally and a confidante, but the close up on her hands swishing the eggs around, and the noise of the slippery mixture privileges the material presence of the image, and interpellates the body of the spectator through this attention to sensations. In a quote where she discusses her use of colour, Varda confirms how a sensual apprehension of the real is at the core of her practice:

Two of the film’s surreal tableaux: the semi-wild kitchen (left) and a plush Eden and its mature Eve (right)

‘J’aime l’irrégularité des sensations colorées ou pas. Le cinéma c’est le mouvement des sensations’ (quoted in Smith 1998: 26).

In the film as a whole, Varda refuses to separate body and mind and interpellates her audience through emotions and sensations. In all the scenes where we face the body in its variety of shapes and states, as it is, for instance, hurting, thinking, moving, loving, the director reminds us of cinema’s materiality and she demonstrates its potential to jolt us into thinking. When she films silent and contemplative sequences, or edits Barbaud’s music over eerie and haunting scenes, Varda also goes against more traditional uses of music and sound. She experiments with various associations, and explores textures and sensations on screen, from the softness of feathers to the pounding hearts of young lovers. Claudia Gorbman, who is an expert on the various uses of music and sound in film, describes utilitarian music as something that ‘lulls the spectator into being an untroublesome (less critical, less wary) viewing subject’ (2003: 40). In 7p., cuis., s. de b., … à saisir Varda, inspired by this space and its surreal mise en scène, creates an eerie rêverie that provokes the spectator and reasserts cinema’s ‘capacity to weave together the sensual and the conceptual’ (Beugnet 2007: 60). She is not, like Noel Carroll argues of Hollywood movies, trying to achieve a ‘flow of action [which] approaches an ideal of uncluttered clarity’ (1998: 180). On the contrary, Varda’s film is destabilising and provocative. It refuses to satisfy our desire for order and to create a fantasy of intelligibility through its assaults on our senses. Varda’s carnal cinécriture reminds us that bodies and minds are splendidly complex and messy, as well as elusive and mysterious. In this hallucinatory rêverie, the camera probes different spaces, different times and different people, establishing symbolic connections while deconstructing relationships, but it does not achieve any sort of plenitude or transparency. What we face time and again in 7p., cuis., s. de b., … à saisir is our thwarted desire to see, to make sense of, and to master the world around us. The only way out of frustration and powerlessness may then be to accept and embrace that our ‘consciousness is harnessed to flesh’ (Sontag 2012: 86), an avenue that Varda explores many times in her work.

Notes

1 ‘Varda’s filmmaking may best be understood, I would contend, as a performance of feminist phenomenology deriving from her woman-subject’s desire, experience, and vision, a carnal cinécriture she has now developed and refined for more than half a century’ (Ince 2012: 14).

2 The website of l’INA (National audiovisual institute) contains several interesting joint interviews, see, for instance, http://www.ina.fr/video/CPF86644616 (accessed December 2012).

3 Aragon was born out of wedlock and was only told once he was an adult that his sister was his biological mother, and his godfather, after whom he had been named, his biological father Louis Andrieux. ‘Un collier aux initiales d’autrui’ (‘a necklace bearing someone else’s initials’) is the way he refers to his father’s legacy. This quote from Le Roman inachevé (1956: 400) shows the burden associated with biological links. His determination to do away with this kind of determinism was also obvious when from 1926, with the publication of Le Paysan de Paris, he removed his first name Louis from the covers of all his books.

4 Henry Miller and Yanco Varda supposedly met in the 1940s, and Miller later published in Circle Magazine, a magazine of art and literature, the article entitled ‘Varda the Master-Builder’.