Understanding the Cyber Battlespace

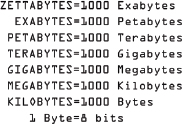

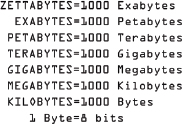

The Internet by 2016 reached an enormous size by any stretch1 of the imagination with units of storage being measured in zettabytes and pages estimated to be over seven billion and growing.2 To give scale to this number, imagine your average one terabyte external hard drive and multiply that by one billion. One thousand terabytes become a petabyte, one thousand petabytes become an exabyte, and one thousand exabytes equals a zettabyte. According to the Internet giant Cisco Systems, by 2019, Internet traffic will reach two zettabytes of data transferred worldwide. With nearly three-and-a half billion users, there was a large haystack in which jihadists could hide their cyber needles as they recruited and planned operations.

Figure 1: By 2016, the yearly traffic on the Internet amounted to over one zettabyte, which is equal to one billion terabytes of information according to Cisco Systems estimates.

The good news is that fighting the E-Jihadists doesn’t require the entire space known as the Internet. Therefore, it is important to identify where terrorists currently operate, where they congregate, and to identify and neutralize the tools they use. The challenge is to beat them before they adapt by pushing them into manageable areas that can be monitored and where cyber weapons can destroy their safe harbors. To be most effective, it makes sense to map out the cyber terrain in question and determine the benefits and limitations of each sector.

Corralling terrorists online could be done by engaging in crackdowns on some platforms such as Twitter and Facebook but intentionally leaving open a platform that intelligence services could infiltrate or monitor. Their adversaries work to erode terrorist confidence in encryption, in large part, by issuing bogus warnings about security weaknesses in platforms in common use. By finding legitimate weaknesses in the hacker or communications tools employed by terrorists, intelligence agencies can exploit these vulnerabilities to track and disrupt ISIS operatives.

At the same time, intelligence agencies and private sector firms benefit from letting terrorists blithely continue to use what they consider invulnerable while allowing them to operate freely—for a time. When ISIS accounts were dropping off of Twitter as a result of takedown requests and internal account checks, some intelligence analysts were concerned when accounts they were tracking were suspended. For example, when Telegram accounts, the secure communications app, went dark for certain users, it closed a window that had been vital to communications intelligence (COMINT) collection. The consensus of those in the intelligence community was that cutting off information that could be garnered from any site should be done with discretion so that law enforcement and intelligence agency programs or operations would not be deprived of a significant flow of intercepts and information.

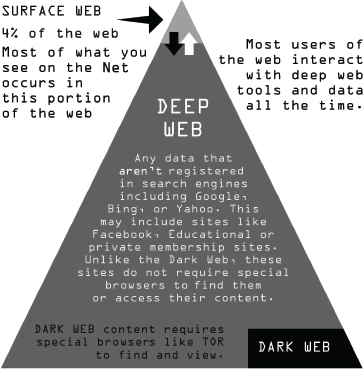

However, despite the enormous digital territory and huge number of Internet users, only a few users of what is called the “Surface Web” are aware of or actively observe what goes on in quite a different layer of the Internet. The data stored in another layer are not accessible to the majority of users. This is called “The Deep Web,” which is data traffic not picked up by the algorithms of search engines. Then, there is the “Dark Web,” where sites are intentionally encrypted and usually accessed by someone knowledgeable about how to find and get onto such sites. Typically, these sites are engaging in forbidden activities ranging from drug sales to weapons or hitman transactions. In order to see the sites on the “Dark Web,” a user must have a specialized browser like Tor, The Onion Router.

Figure 2: The layers of the web. (Source: TAPSTRI)

THE ABOVE AND BELOW

But most terrorist organizations communicate and recruit using the open Internet just like everyone else. Some terrorists have always used sites on both the “Surface Web” and the “Deep Web.” If a nation-state engages in cyber intelligence operations (and has cyber attack capability), it makes sense to avoid trolling through all the online extremist postings, messages, etc.; you end up looking for a needle in an increasingly larger haystack. Cyber counterintelligence agencies should focus on shutting down portals that enable ISIS to spread their radical version of Islam and lure in new recruits. Everywhere. The Internet is (mostly) ubiquitous, accessible, and (with the exception of nations like China) it is “come one, come all.” The global reach of the Internet is its strength; however, it is also its vulnerability, exploited by those who wish to use it to harm others. We are now well aware of the reach of how global intelligence agencies collect raw intelligence (thanks to people like Edward Snowden, the NSA contractor who defected to Russia). We are waging a war against terrorism on many fronts in the physical world, but the darkest of all is the cyber world—a shadow battlefield. The best way to look at this battlefield is to separate what activities occur in what regions. This distinction will allow appropriate and available resources to focus on targets and operations in each zone of activity. It will also identify special conditions and limitations on both ISIS and counter-ISIS forces alike.

To do this we will divide the web in three zones, the Surface Web, the Deep Web, and the Dark Web. Each of these zones has a set of conditions unto itself that obeys certain rules that are as true for the ISIS fanboy or operative as the counter operations crew.

Mainstream companies like Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook operate in the zone known as the “Surface Web.” Though this is the area most seen by Internet users, it encompasses barely 4 percent of the data (usually in the form of pages or downloadable material) that make up the Internet. Instead, most of the data on the Internet is in the open expanse of the unindexed area known as the “Deep Web.” Then there is some, but relatively little, activity in that level of the Internet, in which any exchange of data or communication always involves encryption. There are considerable resources for this, among them PGP (Pretty Good Privacy)—actually a pretty robust form of encryption. If you don’t have a key, you can’t open the door. What transpires in the Dark Web is available only to those who can run special programs like Freenet, I2P, or the browser most commonly associated with the “Dark Web” known as “Tor” or “The Onion Router.” These pages cannot be found via search engines and are hidden behind layers of proxy servers that disguise the location of their elusive website ending with an “onion” address. Thus, setting up a strategy requires determining which zone you are going to approach to select targets.

Identifying terrorist locations on the Surface Web is a good place to start, since they are still quite prolific at posting their materials on Telegram and linking to sites like Archive.org, JustPaste.it, Google drives, and dozens of free file sharing sites. In some cases, they still have blogs that appear briefly with links to videos and other materials loaded with either malware or ad revenue links.

THE SURFACE WEB

The “Surface Web” is available to any web user because of search engines that are accessed by conventional browsers. Search engines use programs to crawl the Internet to make note of pages, media, and other data and store the links for later recall. The method used to gather, parse, and store this information is called “indexing.” In Surface Web, where the vast majority of us operate, our online content creation is indexed and searchable by Google and other search engines and essentially comprises the whole of what lay users would call the Internet. At over fifteen billion pages, the Surface Web is large and filled with most of the content you see day-to-day online. Most of what people consider the Internet is available in the Surface Web area, but it comprises only a small percentage of the web itself. However, the vast quantity of the web data is found in the Deep Web.

Over the first two years after the announcement of the Caliphate ISIS, there was first a flood of ISIS materials across the Surface Web, which made it easy to find their messages of death. Since then, just like their failing campaign to hold onto Iraq and Syria, they have struggled to maintain a position on the Surface Web. Using sites like WordPress and BlogSpot, for instance, ISIS could regularly post batches of video links for followers to share across the Net. Researchers and law enforcement regularly discover the sites and blogs and then file takedown requests. Postings on these and other sites (which will ultimately be shut down) reappear less frequently. The ISIS propaganda machine is responding to these blockages by using Telegram channels that publish the same inciting and often ghastly material. Thanks to Telegram, these ISIS sites are more easily hidden from view.

THE DEEP WEB

The second zone is the Deep Web, or the zone in which data fly below the search engine radar. Beneath the Surface Web, as if the greater part of an iceberg, is a world of data that isn’t indexed but is accessible to browsers even if secured behind a login. When you move from the daylight of the Surface Web to the hidden caverns of the Deep or Dark Web, the rule becomes “Unless you are in the know, you don’t know.” If you don’t know how to get there via Chrome, Explorer, Safari, etc., and if the site isn’t found and indexed by Google, then most likely it is “deep web” material.

Most users of the Internet run into the Deep Web all the time if they log into websites that have usernames and passwords. An example of something found in the Deep Web would be a jihadist forum that requires a sign-in and doesn’t appear in Google but is visible in Google Chrome or similar browser.

The activity of ISIS and related groups in the Deep Web is largely found in the forums that are intentionally hidden from Google and other search engines. Sometimes it is obvious that a website is seeking to avoid being found. Many forums and propaganda sites were installed a directory away from the root of the website. Example: (“website.com vs. “website.com/vb/”). It doesn’t take much to prevent Google from searching a website or its contents. The most common way is a simple text often called “robot.txt” that simply tells the search engines to ignore the website and its contents.

Efforts are underway to map out the Deep Web including Memex, a Deep Web crawler used by law enforcement. There are privacy advocates who have expressed concern about using this method as a form of data mining, operations that would be illegal unless authorized by a search warrant. They are, indeed, disturbing when the “catch” trawled by its big and indiscriminating net includes innocent people.

According to some informed sources, there are five hundred times more pages in the Deep Web than in the Surface Web. There is no distinction between Deep Web and Surface Web when it comes to illicit activities. The chances of materials being discovered in searches are greater on the Surface Web than the Deep Web, but the Deep Web can be surveyed and mapped for terrorist activities by a combination of OSINT or Open Source Intelligence and HUMINT or human intelligence—information obtained by and from people. There is also no distinction between the Deep Web and the Surface Web when it comes to anonymity.

THE DARK WEB

Then there is the “Dark Web,” sometimes known as the “Cipherspace,”where users are required to use special browsers to access an array of websites including ones with illicit content that cater to a range of criminal, political, and social interests that are deliberately hidden from view. Not only can search engines like Google and Bing not discover and register these sites, they are only viewable through custom browsers like Tor (a.k.a. The Onion Router). Tor was developed in the 1990s by the United States Naval Research Laboratory. In April 2016 in its French publication Dar al-Islam, ISIS warned that Tor was being used by its enemies. The article claimed that intelligence agencies had breached sites and put up honeypot sites to catch visitors. Some jihadis claimed the NSA was specifically targeting Tor users for surveillance. Other browsers that operate like Tor include I2P, Freenet, Subgraph OS, and Freepto.

Dark Web sites and forums still require user access in most cases, but there are some that still have ISIS/AQ-related news announcements or other bits of data that can help investigators put a larger picture together. Although the Deep Web is vastly larger in comparison to the Surface Web, the area of the Dark Web is significantly smaller than the Surface Web.

The Dark Web also provides plenty of opportunities to use anonymous currency like Bitcoin. Started in 2009 by an unidentified person who used the cover name Satoshi Nakamoto, Bitcoin is a decentralized digital virtual currency used online, especially in the Dark Web, to conduct transactions. Bitcoin is also the name given to the peer-to-peer financial network in which the currency operates. Because of the inability to track the movement of this currency, Bitcoin has been banned in several countries.

Bitcoin has been gaining traction in common markets. Dozens of businesses are opening up to the use of Bitcoin as currency. A few major businesses that accept Bitcoin as currency include Overstock.com, Subway, Home Depot, CVS, and Sears.3 ISIS members have used it, as well. One was Virginia teenager, Ali Shukri Amin, known online by the name @AmreekiWitness. Amin was behind the publishing of a document and website attributed to the Islamic State that was soliciting donations of Bitcoins for the terror organization. He was arrested and sentenced to eleven years in prison in August 2015 on material support charges.4

Whereas sites on the Dark Web may be beyond the grasp of the average search engine, the US government hasn’t simply given up and let the activities of online criminals elude their reach in the Dark Web. In November 2014, international law enforcement knocked down hundreds of websites that had been engaged in various criminal activities ranging from drug sales and money laundering to the sale of weapons and illegal pornography. The alleged founder of Silk Road, an illicit Dark Web drug market, was arrested in San Francisco.5 Along with Silk Road, two other drug sites named Hydra and Cloud 9 were busted in international seizures. The international effort was dubbed “Operation Onymous.”6

During Operation Onymous, one site knocked off the Dark Web was purported to be an ISIS-affiliated financial donation site under (bc3nbr42tdnqamvs.onion) where contributions could be made via Bitcoins. Instead, it was a clone of the pro-ISIS American user’s AmreekiWitness site. One blogger, Nik Cubrilovic, noted that the FBI knocked down several fake sites but missed the actual AmreekiWitness-operated site, which remained active for a period of time after the Operation Onymous effort had run its course.

DARK WEB SEARCH TOOLS

There have been programs introduced that search the Dark Web for information that law enforcement wants in its various investigations, ranging from drug cases, illegal pornography, and human trafficking to hired assassins and terrorism. One tool used for this is Memex, developed by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). As noted previously, Memex is a program that scours the web using crawlers that have been designed specifically to deal with the Dark Web. It is able to get past the conventional methods for avoiding search engines. One method is to place a simple text file on a website that tells Google’s search engine bots to ignore the site. A key feature of Memex is that it also evades detection. Thus, if a site with terrorist materials is located by Memex, it doesn’t leave behind any signs that it has searched the site.

Memex was specifically cited by a New York City District Attorney as being key to breaking several cases of human trafficking.7 The software’s design allows investigators to crawl beyond the Surface Web to areas that specialize in human trafficking, like prostitution sites, to aid in building perceivable patterns of activity.

Used against ISIS, a program like Memex can help identify networks under the Surface Web by searching the vast visual publications shared by ISIS or by engaging in crawls for specific terms associated with ISIS/AQ or related groups. Since groups like ISIS’s CCA (Cyber Caliphate Army) have standardized the branding of their group, graphics, and related hacking hashtags, a search though the Deep Web for all locations with those graphics or phrases is a first option. What is required for a search to locate online depots for videos would be as simple as knowing the name of a release, having a related banner, or wilayat (the regional ISIS substates) information and conducting a search on for those specific items.

DEEP WEB VS. DARK WEB

While Dark Web sites elude detection by most search engines, what enables certain ones to distinguish the difference between Deep and Dark Web is how the pages are accessed. Deep Web sites can be accessed typically with any browser, but there may still be sign-in limits, and users must know how to get to content since, as noted earlier, it will not be listed in search engines like Google and Bing. In contrast, Dark Web sites are encrypted and only accessible via Tor or similar browsers. They are found via word of mouth. The difference between dealing with matter on the Deep Web and on the Dark Web comes down to how you detect and attack their communication centers.

Many assume that Dark Web means the user and activity are hidden and safe from prying eyes. There is a drawback to trying to use Tor in isolated sectors. To his misfortune, Harvard student Eldo Kim found out that Dark Web anonymity did not apply when he sent a bomb threat to the school in order to avoid a final examination. He supposed that he would send the threatening email message via Tor and that would help to anonymize his location and identity. What he didn’t count on, though, was that Harvard was able to detect his usage because he was the only person using Tor on the network at the time. As a result, he was arrested, expelled from the school, and acquired a permanent criminal record.