Software of the Global Jihad

As average Internet users around the world know, online web tools are very useful—particularly for ISIS operatives and fanboys. In many ways their behavior on these websites, social media, and apps was not unlike the average Internet user sharing the latest news or music clip or video with her friends. But in a very distinct way, the ISIS/AQ followers are using the tools for ongoing operations, to celebrate perceived victories, or to recruit and train members.

The use of tools by ISIS/AQ and other groups was largely dictated by the perceived security of any particular tool from detection or interference by counteroperations, including those carried out by law enforcement or the military. Frequently updated OpSec postings by ISIS on various channels and pasting websites cover not only cell phone security, but discussions about the perceived security of the apps or social media outlets recommended and used by terrorist groups. There are Telegram channels like the Horizon (Afaaq) channel dedicated to the lone discussion of cyber security for the terrorist user. The channels associated with the Cyber Caliphate Army are often filled with up-to-date tech posts from American or European tech sites and their discussion on technology.

Security was and still is a major concern for terrorist groups, which work hard to stay well informed about which apps will help them elude law enforcement and intelligence agencies. Similarly, activist groups stuck in Syria between Assad and ISIS uses many of these apps to avoid detection by both ISIS and the Assad forces. But the opposition to ISIS mounts counteroperations that seek not only to detect but also intercept or interrupt the communications among operation organizers, recruiters, and end users.

One effort that ISIS employs consistently is devoted to maintaining a level of operational security that at least successfully eludes the surveillance of intelligence services. Many cases before the US courts showed that the suspects were given specific instructions on phone purchases, messaging systems, emailing, and destroying traces of activities.

Take, for instance, the case of Jalil Ibn Ameer Aziz in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. In the complaint, it is alleged that Aziz told his coconspirator to switch to a “US-based messaging application that allows for encrypted communications.” Also, upon starting on his way to Syria, Aziz told his conspirator to wipe “pro IS materials” from his laptop. Another example is the Hendricks case related to the Garland, Texas, attack, where strenuous efforts were made to direct others to specific messaging apps and to advise operatives and sympathizers about how to use an anonymizing app.

For all the work these ISIS channels or posts put into advising followers on how to avoid detection, many cases in the United States and Europe show that the end users were not always so savvy at executing the advice.

In addressing the security skills of terrorists, CIA Director John Brennan spoke at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in November 2015 and said:

But I must say that there has been a significant increase in the operational security of a number of these operatives and terrorist networks as they have gone to school on what it is that they need to do in order to keep their activities concealed from the authorities.1

The constant endeavor to track terrorists using their communication tools involves more than simply trying to crack the encryption of their phone and devices or figuring out which social media platform ISIS prefers for the moment. It also involves looking at the metadata that are produced—the raw digital fingerprint and location information, knowing the flaws and slipups of terrorists using these tools, and knowing the trends that the groups or members themselves recommend and why.

END-TO-END ENCRYPTED MESSAGING APPS

End-to-End messaging apps are often cited as a key tool in ISIS planning and recruiting. ISIS used a range of messaging apps that were largely determined by perceived security and limited often to free downloads for Android devices.

Telegram

Figure 15: Telegram Logo.

Released in August of 2013, Telegram was the most popular end-to-end messenger for ISIS, and by the summer of 2016, Telegram had become the leading app for mass proliferation of ISIS media and announcements.

Telegram added “channels” to its app usage in September 2014, and with this came a burst of ISIS related “channels”2 and a spectrum of channels catering to different groups within the jihadist world, from ISIS and al-Qaeda to more nationalistic groups like the Taliban using these channels. Channels are accessed as “open join” options in some cases, whereby anyone can participate and/or by special invite or “short term join” option in others. The channels post a wide array of propaganda and chatter about any number of events in the ongoing war on the apostates and unbelievers. This may be slide shows and videos from official ISIS media or the various satellite groups like Amaq News Agency or shout-outs announcing that a Twitter channel is back up after deletion.

Developed by Nikolai and Pavel Durov, the app features “secret chat.” According to its founder, “The No. 1 reason for me to support and help launch Telegram was to build a means of communication that can’t be accessed by the Russian security agencies, so I can talk about it for hours.”3 As of February 2016, Telegram user count hit 100 million users.4 One example of the effect of this growth of users is Najim Laachroui, who was a suspected accomplice in the March 2016 attack on the Brussels airport. He was alleged to have used Telegram to plan the operation with Syrian-based ISIS operatives. He had turned to Syrian allies to help test explosives he could use in attacks in France. Had authorities been able to intercept these messages, they might also have learned the discussed plans to attack a soccer championship or that he and colleagues were living in three separate safe houses.5

He maintained communication with Abu Ahmed, an ISIS commander in Syria, via Telegram. He used the app to report to Abu Ahmed that they had lost their AK-47 ammunition in the March 15, 2016, raids in Belgium. In addition, investigators found his laptop and recovered more data including audio and texts.

Around the world, not much has been done to limit ISIS’s use of Telegram. Iran is notorious for controlling Internet usage by most of those in the population. The Iranian government has cracked down on Telegram users, arresting over 100 group administrators and charging them with “immoral content” propagation.6

After the Paris attack in November 2015, ISIS began encouraging its followers to shift to using Telegram as a preferred messaging app. The claim of responsibility for the attacks was posted on channels related to ISIS. In the subsequent months, it would become common for analysts and news media outlets to turn to ISIS-related Telegram channels and media to keep up with claims of responsibility.

When it came to dealing with ISIS on their channels, Telegram stated to ProPublica that it had taken down more than 660 public ISIS channels as of July 2016.7

To back up its claim that it was maintaining security, Telegram launched a contest in early 2014 to invite hackers to break its encryption with a $200,000 Bitcoin prize for the hacker who could break their encryption and intercept a message in a “secret email” published by Telegram “backer” Pavel Durov.8 By March 1, 2014, no winners were announced, and the contest was relaunched with a larger Bitcoin prize of $300,000. By the end of the contest in February 2015, there were no winners.9

ISIS issues warnings about channels and users who might be posing as ISIS members but instead turn out to be law enforcement seeking to discover the identities of the pro-ISIS users.10

In late November 2015, Sony Mobile Communications consultant Ola Flisbäck discovered metadata being displayed by the Telegram app that allowed for observing the activity of users mainly visible when using a “third party client such as vysheng’s CLI client” to see and display the data. He pointed out that by observing the metadata you can “make guesses about who’s talking to who” as well as data from other users the “victim” had in common with the “attacker.”11 Additionally, the targeted user or “victim” is not notified when they are added to the “attacker” contact list, and the “attacker” will receive subsequent metadata from the target. Thus an attacker can possibly ferret out the “target” by comparing contacts.

In February 2015, Zuk Avraham discovered he could see portions of texts by dumping the process memory and examining the “data-at-rest” information instead of the “data-in-transit” results.12 In doing so, he was able to see portions of his test messages including the deleted messages.

Released in January 2010, WhatsApp is another end-to-end encrypted messenger app owned by Facebook. The result of an effort by Brian Acton and Jan Koum, WhatsApp was created in February 2009. First it started as an app that showed if the user was online before becoming a messaging app. Facebook purchased the company on February 19, 2014, for $19 billion. In late August of 2016, it was announced that metadata from WhatsApp would be shared with Facebook.13

WhatsApp claimed as of February 1, 2016, it had over one billion people using its messaging app worldwide.14

The app features Instant Messaging with end-to-end encryption. In addition to text, it is capable of sending photos, audio messages, and pdf documents, so there is a metadata record still stored that includes phone numbers and timestamps that can be used to build a picture of communications between parties.

For example, in April 2015, Milanese police heard a Moroccan receive instructions to “Blow yourself up, O Lion” via a secret wiretap of his WhatsApp communications app. Abderrahim Moutaharrik was arrested when he used an Indonesian phone with WhatsApp after the audio messages from Mohamed Koraichi had been detected by Italian police.15 He was preparing to attack a synagogue in Milan. He had planned to leave with his wife Salma Bencharki to go to Syria.16 In a ProPublica article called “ISIS via WhatsApp, Blow yourself up o Lion,” an unnamed FBI official said, “Then you’ll see one of them says: ‘OK, reach out to me on WhatsApp.’ At that point, we can’t do anything.”17

WhatsApp was banned in Brazil, which kicked off around ninety-three million Brazilians after the Facebook-owned company refused to comply with court orders to turn over messages in drug cases. Facebook responded by stating that they could not help because the messages weren’t stored and are encrypted.18

Bangladesh temporarily blocked access to WhatsApp along with Twitter, Facebook, Messenger, Tango, and Viber in November 2015.19 The crackdown came in conjunction with the announcement of a death penalty sentence handed down to members of the political opposition, leading some to suggest that this had been done to stifle the reaction of supporters of the two men sentenced to die.

In March 2014, Bas Bosschert wrote a post on his blog revealing how to retrieve messages by stealing the database file and by intercepting it as it was being written to the SD card. The blog post went viral, according to Bosschert. Additional security issues arose including vulnerability to malware links and the ability to track a targeted user with a program no longer available on the web called WhatsSpy. WhatsSpy allowed the application user to track a target including their “online/offline status,” “profile pictures,” “status messages,” and “privacy settings.”20

Signal

Released in July 2014, Signal is a free end-to-end communication app with encryption that works on both Android and iPhone.21 It is sometimes known as the “preferred” or “favorite” messaging app of Edward Snowden. In addition to texting, it supports voice calls.

In the hands of ISIS, Signal proved to be too tempting not to break apart and exploit for development. Indian officials say that ISIS member Abu Anas said he discovered Signal as an alternative to possibly monitored apps like WhatsApp, Facebook, and Instagram.22 He was tasked to reverse engineer the open-source app and develop an ISIS communication app based on the popular app.

Wickr

Released in December 2014, Wickr is an end-to-end encryption messenger based in San Francisco started by a group of security and privacy experts as a project in 2012. This app features automatic expiration of messages. Just like the famed spy lore of self-destructing messages, Wickr messages can be set to expire in minutes or days. This messaging app has been mentioned as one of the safest by ISIS supporters. For example, Australian Jake Bilardi, a teen who joined ISIS, directed would-be recruits to contact him via Wickr in a Telegram posting.23 Frequently, when news reports come out about the security of well-known apps like WhatsApp, lesser-known apps like Wickr become the fallback favorite for a period of time. Wickr gets high marks for its ability to erase messages.

Surespot

Surespot is an open-source app that features end-to-end encrypted instant messaging for both the Apple iOS and Android. It is capable of texting and sending images and voice messages. It is capable of “multiple identities” on the same device. Like Wickr, it is capable of message destruction.

The ISIS publication “Hijrah to the Islamic States” repeatedly references Surespot for its security. For instance, in a list of Twitter accounts to contact for recruiting, they advise contacting them via Surespot: “These people live in the Islamic State. They have Surespot and other private messaging apps.” And “The Brothers on Twitter share their Surespot and Kik Messenger accounts.”

For example, when British teenagers Shamima Begum, Kadiza Sultana, and Amira Abase disappeared, investigators combed over all their web communications. In time, they found that the girls had been lured by ISIS to come to Syria. In tracking their path to Syria, they found that the girls had initially talked on Twitter before they were told to move the conversation to Surespot.24

Australian Mohamed Elomar headed to Syria and became infamous for a picture showing him holding up the heads of two dead Syrians; that got him banned from Twitter.25 A former boxer from Australia, Elomar became a fiery social media character taking to Twitter with suggestions “get an AK47” or “How to make C4” and for his followers to contact him on Surespot.26 His evil life ended in a drone strike in Syria.

Threema

Released in December 2012, this Swiss-made messenger features end-to-end encryption and can send multimedia, voice messages, and other files. It ranks a six out seven in its “Secure Messaging Scorecard” by the Electronic Frontier Foundation. When Edward Snowden came forward and discussed NSA surveillance in 2013 and after Facebook bought WhatsApp in 2014, Martin Blatter, the CEO of Threema, stated to Business Insider that the company saw a doubling of downloads in Threema “overnight.”27 According to Threema, “messages media are stored” up to fourteen days if not delivered on servers or are deleted when delivered, “whichever happens first.”28 However, Threema is not free. There are versions that have posted on terrorist websites, but without a source of the free file, the OpSec (operational security) would be risky.

In late January 2016, the Cyber Caliphate notified its followers to move to Threema. The Times of India stated that the suicide squad that took hostages at the Holey Artisan Bakery in Dhaka, Bangladesh, on July 1, 2016, was sending messages via Threema to ISIS’s al-Amaq agency.29

Figure 16: Afaaq Electronic Foundation recommended messenger Threema in JustPasteIt graphic.30

Silent Circle

Released in October 2011, SilentCircle was named by ISIS as a preferred app. Alarmed, the developers changed the app to increase the accountability of those who used it. Silent Circle, which was cofounded by former Navy Seal Mike Janke, works with both government and private intelligence agencies.31

Viber

Viber is a voice-over-IP and instant messaging app designed for Android and iPhone. It allows users to call or text for free via Wi-Fi connection. In an interview with Richard Engel, jailed former ISIS fighter Ahmad Rashidi stated that ISIS would frequently use Viber and WhatsApp to communicate with people in Europe. He also noted that ISIS fighters didn’t use cell phones but preferred to use laptop apps.32

Bangladesh temporarily blocked access to Viber in November 2015 as well as over a half-dozen other social media companies.33

Viber was also used to pass the bad news back to the families of fighters. New Zealander Karolina Dam’s autistic son Lukas went to fight for the Islamic State in May 2014. By December 2014, Lukas was no longer responding to his mother via Viber. A month passed before she received a response from someone else who had Lukas’s phone. “Can you handle some bad news?” the text read. “Yeah, honey,” she responded to the text. “Your son is in bits and pieces. This is what Denmark USA has done to him. I know it’s hard, but it’s true.”34 The most interesting component was not that he was dead but that ISIS kept his mobile phone and continued to use his Viber account after his death as a form of operational security.

Skype

One of the most widely used communication apps in the world is Skype, now owned by Microsoft. It provides video and voice services via smartphones, laptops, and desktops and the service is free. Founded in 2003, it has become so synonymous with video chatting that it is used as verb. However, the communication system isn’t particularly secure, as revealed in several security reviews including one in 2013 by Ars Technica aided by Ashkan Soltani where messages specifically sent to test the encryption were easily detected.35

This was not lost on law enforcement. Maria Giulia Sergio, once an Italian Catholic, married a Muslim from Albania. In 2014, she went to Syria from her home in Inzago outside of Milan with her husband to join ISIS. She used Skype to communicate with her husband and her family.36 “When we behead someone, I say we because I too am part of the Islamic State, when we take such action, we are obeying the sharia,” she said via Skype.37 She remained determined to convince her father, mother, and sister to convert to Islam and come to Syria. Eventually they relented, but before they could make their journey to Syria, Italian police arrested them. The authorities had been monitoring the Skype communications for weeks.38

American ISIS recruit Shannon Conley used Skype to communicate with an unnamed thirty-two-year-old Tunisian who “claimed to be in Syria fighting on behalf of ISIS,” according to the complaint filed against Conley. She even asked her father to bless her upcoming marriage to the Tunisian and permission to go to Syria. The father declined. After her arrest at the airport, her residence was searched, and the agents found CDs and DVDs that were marked “Anwar al-Awlaki.”39 British ISIS predator Ahmed Canter tried to lure a Canadian TV reporter from Global News via Skype after she went undercover as a fifteen-year-old. He messaged her via Twitter first before moving on to Skype videos.40

In a similar story, a French reporter had an encounter with an ISIS recruiter using the name Abu Bilel. Shortly after talking to her on Facebook, he suggested, “We should talk over Skype.” Using a pseudonym of “Melodie,” she had created a full Skype profile to talk with this person. She informed her editor and included a colleague in the process. Abu Bilel skyped her from his car.41

OTHER WEB TOOLS

Not all web apps and tools fit neatly into the communications or social media categories. Many facilitate the ability to have the messages sent securely using encryption, and some give the sender the ability to hide from detection or tracking.

TrueCrypt

TrueCrypt is a program for Windows, MAC OS, and Linux that is used to encrypt files. The program’s support not only ended, but on the Sourceforge page (the developers used for the software), a warning was published that said, “Using TrueCrypt is not secure as it may contain unfixed security issues.”42

Returning fighters claimed that when they were dispatched for attacks, they were given thumb drives with a series of programs to avoid their being traced, one of which was TrueCrypt.43 Why did ISIS choose this tool if it has such security issues? In an exposé on NSA’s capabilities, the German news site Spiegel said the Snowden document dump revealed that NSA had “major” problems cracking TrueCrypt. How does a program that NSA has trouble cracking get described by its developers as having “unfixed security issues”? The reason for that may never be known.

Tor is a free browser used both to surf the Surface Web with an increased amount of anonymous protection and to access websites found on the Dark Web, sometimes known as the Tor network.44 To anonymize the user traffic, the Tor browser starts by sending out a request to the Tor network directory. The directory supplies the computer with the appropriate location, yet the information between both the requesting party and the host is anonymized. To do so, the network is designed to pass the requests across a series of random computers around the globe until the destination is reached. The process repeats in reverse, disguising the hosting server to the recipient. As each request passes to the next computer, the Internet Protocol address of the last computer is stripped away like an onion layer and replaced with the current relay computer’s IP. This effect is like peeling an onion back layer after layer, thus The Onion Routing or Tor.

T.A.I.L.S.—The Amnesic Incognito Live System

This Linux-like operating system (OS) was often cited as the preferred system of Edward Snowden, journalists Glenn Greenwald, and ISIS. Booted per session from a USB stick or DVD, the OS was geared for privacy. The OS does not write to hard disc, which decreases the chances that logs and data can be recovered for forensic examination and decreases vulnerability to malware. The OS can be used on a computer with a conventional OS but will leave no trace of the TAILS activities.

The system comes preloaded and ready to work on both the Tor and the I2P networks and is loaded with an array of encrypted tools for encrypted messaging, password generators and managers, metadata cleaners, and more. Its base browser is Tor.45

The NSA has said it was concerned about TAILS and combination usage with other encryption that prevents their ability to scoop data from these users. Developers have reported that the agency has been pushing for backdoors that would allow intelligence or law enforcement access.46 TAILS 2.0 was released in January 2016.

JIHADIST DEVELOPED AND DISTRIBUTED APPS

Jihadist terrorists did not always trust the source applications that were popularly used, particularly after the Edward Snowden revelations that revealed that NSA was working with many software developers. Based on this mistrust, they often attempted to write their own programs to encrypt and transmit secret communications.

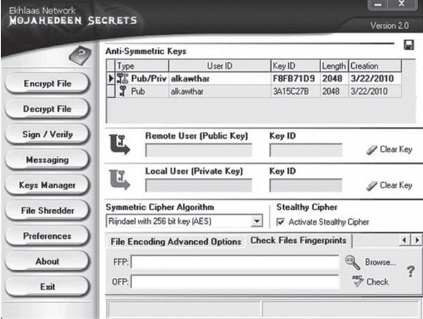

Mujahedeen Secrets

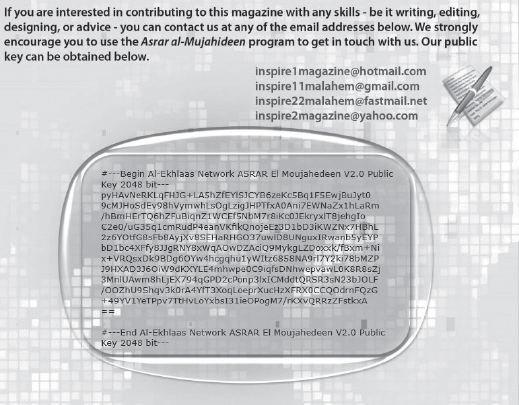

Al-Qaeda began publishing encryption tools in 2007 when its media group, the “Global Islamic Media Front” or GIMF, released an encryption program for use on Windows known as “Asrar al-Mujahideen,” sometimes called “Mujahedeen Secrets.” Used in conjunction with email, the program would allow operatives and supporters to encrypt their messages, including the ability to create a private key. It was updated to Version 2.0 in 2008. Al Qaeda would later release a segment in the first edition of AQAP’s Inspire magazine called “How To Use Ansar al-Mujahideen: Sending & Receiving Encrypted Messages” that showed how to operate the program.47

Figure 17: Screenshot of Mujahedeen Secrets 2.0 from Inspire magazine #1 (Source: TAPSTRI)

The program, intended to be used off a USB flash drive, allowed users to “Generate keys” in the “Keys Manager,” which creates public and private keys. Just like the key to your home or your car, a digital key is personal and in this case is used to confirm your identity in encrypted messages. When messages are sent and received, if the key’s line matches up, the messages will decrypt and contents can be read. The public key is sent to the associated contact, who returns a copy of their public key. Al-Qaeda of the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) even published a copy of its public key in the same first edition of Inspire magazine.

Figure 18-Encryption Key published in last pages of Inspire magazine #1. (Source: TAPSTRI)

Morton Storm, the Danish double agent who worked alongside the late terrorist Anwar al-Awlaki, said he was shown how to use the program by al-Awlaki himself. The information he decrypted from al-Awlaki was later passed on to the CIA.48

Tashfeer al Jawwal

Like its predecessor, Mujahedeen Secrets, al-Qaeda’s Global Islamic Media Front (GIMF) group released an encryption app for Android Mobile in September 2013 through the jihadist forums. The group claimed it was the “first Islamic encryption software for mobiles.”49 However, al-Qaeda didn’t demonstrate any new ability to encrypt. They used existing Twofish encryption designed by master American cryptographer Bruce Schneier and the “Twofish” team in 1998.50 In releasing the program, GIMF published tutorials on how to use the program in Arabic, English, Indonesian, and Urdu.51

Asrar al-Dardashah

On February 6, 2013, al-Qaeda’s GIMF released an encryption plugin for the instant messenger Pidgin using RSA 2048 encryption.52

Amn al-Mujahid

On December 10, 2013, one of al-Qaeda’s groups, the al-Fajr Technical Committee, released a Windows program called Amn al-Mujahid or the “Security of the Mujahid” program in addition to a 28-page manual.53 In June of 2014, they released a version as an Android app. Again, like the other al-Qaeda creations, the encryption relied up Twofish encryption.

ENTER THE ISIS APPS

By 2013, ISIS was developing apps to meet its desired encryption, communication, and indoctrination needs. Notably, the Amaq News Agency and al-Bayan radio apps were often promoted as a way to follow the latest events in the terror organization.

Asrar al-Gurabaa

On November 27, 2013, ISIS launched the asrar006.com site. The Asrar (Secrets, in Arabic) site was used as a web-based encryption tool created by ISIS developers found via the Tor site.54 In December 2013, the AQ-friendly GIMF group released a statement saying the app was “suspicious and source is not trusted.”55

Figure 19: Amaq Banner. (Source: TAPSTRI)

Amaq News Agency

The Amaq News Agency released an app to feature its headlines for ISIS followers. By using it, you will never miss news of key events, or you can monitor publications and learn about ISIS leaders killed in action. It is designed for use on Android phones.

Figure 20: Al Bayan Banner. (Source: TAPSTRI)

Al-Bayan Radio

Known as an FM radio signal station on 92.5, al-Bayan radio delivers its version of the headlines from around the Islamic State from Mosul, Iraq. The group released a new Android app via Telegram and links to Archive.org in early February 2016. The file was released as BayanRadio.apk.

Figure 21: Huroof Banner. (Source: TAPSTRI)

Huroof

An Android app aimed at teaching children Arabic, it is loaded with Jihadist propaganda including AK47 symbols, ammunition, tanks, and more. Released through al-Bayan, Huroff was published on Telegram channels in May 2016.

THE ISIS HELP DESK

In November 2015, the news broke of an ISIS Help Desk designed to help supporters of the terrorist organization use their gadgets and Internet tools with 24/7 support. However, there was no Help Desk, as NBC and others reported. Instead, the concept was a media misunderstanding of information given to them by Dr. Aaron Brantly of the West Point Combating Terrorism Center (CTC).56 He had briefed them that ISIS was indeed working to train potential recruits on how to safely navigate the web for both coming to Syria and for operations around the world.

Figure 22: Afaaq Banner. (Source: TAPSTRI)

THE AFAAQ ELECTRONIC FOUNDATION

On January 30, 2016, a new Telegram channel appeared accompanied by a Twitter channel under the name Afaaq Electronic Foundation, sometimes known by the English word Electronic Horizon (Afaaq) Foundation. According to an unnamed “security specialist” in an article for The Hill, EHF comes after a fusion of groups including “Information Security” and “Islamic State Technician.”57

Another addition to the misconception that ISIS had a notion of an ISIS “help desk” was the publication circulated on JustPasteIt without attribution to the legitimate Kuwaiti security firm who developed it for training materials in 2014. Called the “ISIS OPSEC Manual” by Wired initially, it was in fact created to help journalists operating in sensitive regions by Abdullah al-Ali of the Cyberkov firm. Following the news of this connection, a small war of words broke out over Twitter between parts of the group Anonymous and the CEO of Cyberkov. Anonymous threatened the firm with DDoS attacks on the company website if it did not remove a post written about Anonymous and affiliated group GhostSec.58

ISIS Responds to the Encryption Battle

If you take a look at the published reactions from ISIS/AQ, you can see that, from just after the headlines hit about Edward Snowden’s intelligence leak, the ISIS operational security section (OpSec) sent out advice and reactions showing they were clearly paying attention and not only making adjustments but also making progress in learning better ways to hide and to obscure their intended covert activities.

The AQ Global Islamic Media Front (GIMF) said, “Take your precautions, especially in the midst of the rapidly developing news about the cooperation of global companies with the international intelligence agencies, in the detection of data exchanged over smartphones.”59 It was also pitching its new encryption app Tashfeer al-Jawwal, which was released just after the Snowden leaks.60 When the Afaaq Electronic Foundation was announced in January 30, 2016, it specifically noted the Snowden leaks as a reason jihadists should ramp up their own security. There is little guessing about whether ISIS, al-Qaeda, and other threats to the United States benefited from the leaks—the releases were of great value to their understanding of US operations.

At one end, there are those who advocate forcing tech giants to release skeleton keys to government agencies so that under court order they can retrieve data on a target without interference from the tech company protesting, “but the data is encrypted.” This “backdoor” technology has been criticized for several reasons, among them the fact that once you make such a choice, you have to consider that backdoor now exists for everyone including nefarious actors. At the other end, after the San Bernardino case, Apple CEO Tim Cook made this clear—such a backdoor would be for good guys and bad guys.61