Jihadi Murder & Cyber Media

In a truly shocking scene, a journalist named James Foley was executed by beheading with a bayonet by the British terrorist Mohammed Emwazi, a.k.a. Jihadi John on August 19, 2014. The video included a direct taunt to the American president, Barack Obama, by the Londoner wearing all black. The shock resulted in coverage that frequently obsessed with the “Hollywood style” production of the video they were now covering. Shot in High Definition (HD), the propaganda videos of ISIS grabbed the attention they sought by using better quality cameras, editing skills, and, most important, a clear narrative. ISIS videos said the caliphate was here and anyone who got in their way would be beheaded.

In 2004, AQI leader Abu Musab al-Zarqawi killed Nicholas Berg the same way; it was captured on a grainy tape in a Sony handycam video. It was shuttled to the web by his associates, including Abu Maysara, the first AQI information minister. Within the first twenty-four hours of the Berg video being uploaded from London to al-ansar.biz in Malaysia, it was downloaded more than a half-million times. US authorities had previously tracked this website from other locations including Alexandria, Egypt. Abu Maysara had to adapt how to post the Nick Berg video. Due to limitations at the time, AQI’s efforts to publish the video ran into file-size limitations in emails, user access issues in Yahoo, and limited footprint on the web for jihadist forums. He was, however, able to find a file sharing site called YouSendIt, which allowed the user to send out links to anyone on the web.1 This model of propagation was adopted by ISIS. Tease the video through small clips or still images on Twitter, drop it into a file sharing folder, and let the world download it from the site. What AQI had pioneered, ISIS had perfected. Tens of millions of downloads occurred after the James Foley video, and the caliphate harnessed the chariot of visual media to spread their message of fear.

THE ISIS VIDEO MEDIA STRUCTURE

ISIS official videos have specific logos and styling that are very distinctive and bear the stylistic signature of the regional and central branches. The head production house was al-Furqan Media. The second tier outlets are focused on messaging across the entire ISIS region or beyond, as if the message comes from a central government. They include an-Naba, a weekly newspaper; Maktabat al-Himmah, a publications center that releases printed publications; and al-Hayat Media, the outward bound messaging voice for ISIS. Al-Hayat Media serves to broadcast the ISIS message beyond the regions under the caliphate’s control and beyond the Arabic language audience. There are also the regional centers divided by Wilayah, or states. Each of these centers has their own logo and graphic presentation style. For instance, Wilayah Dijlah videos use a 3D intro that shows their logo appearing from water to emphasize its association with the Tigris. Each center may focus on presenting the events in the allocated region they cover or may be turned to speak against an enemy. In a few cases, many regional centers were used to send unified messages to a particular ISIS region or a potential ISIS affiliate. “Messages for the Maghreb [Western North Africa]” were sent from across the ISIS regional centers to incite action in Morocco, Tunisia, and Algeria. In other cases, “Messages to Somalia” releases came in early October 2015 as the terrorist group Al-Shabaab was caught in contemplation on joining ISIS or remaining in its loyalty to al-Qaeda. The ISIS messages were aimed to persuade the group to swear an oath of loyalty or Ba’yat to the Caliph Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

Al-Furqan Media

This was the center where it all began under al-Zarqawi. In 2006, AQI began releasing videos of its campaigns, and the production house for those operations was named al-Furqan. With hundreds of releases, before the group called itself ISIS, al-Furqan was the granddaddy media organization. Starting with series like Hell of the Romans and Apostates in the Land of Two Rivers, al-Furqan mastered the art of jihadist video and terrorism snuff films. The Hell of the Romans series was a batch of over a hundred near-minute-long clips showing various AQI attacks from shootings, bombings, grenade attacks on US, or “apostate” troops from around Iraq. These were first released January 20, 2007, and continued until August 30, 2009.

In June 2012, ISII released the first of four videos called Clanging of the Swords, which would be recalled repeatedly in other AQI releases as a suggested title for viewing. The hour-long video starts by attacking the Shia as apostates before turning to SVBIED attacks and ending with house raids with silencers.

The second volume, running just under an hour, was filled with footage from a Haditha attack on March 5, 2012, where approximately 40 AQI fighters killed 20 police officers. 2 The video shows how the attackers put the operation together, how they disguised themselves as SWAT team members to get past the checkpoints and attack the police officers. Col. Mohammed Shafar was one of those killed. He had been helping the fight against AQI with “Awakening Movement,” a Sunni militia. The video shows the attackers’ view of the events of the evening.

In a “Cops”-style first-person video format, the video takes you through three checkpoint raids before they reach Haditha. The officers are first subdued after being swarmed by AQI attackers dressed as SWAT officers and bound. Then later you see them murdered by shots to the head with silencer pistols.

The third Clanging of Swords featured footage of the Destroying the Walls campaign. Al-Baghdadi called for the campaign in July 2012. One of the stages of the campaign would focus the release of allies from prison. In this video, prisoners from Tafirat prison in Tikrit are featured after they are freed by AQI. Iraqi officials state that files on who was freed were destroyed during the attack.3 The fourth Clanging of the Swords came many months later and opened with a drone video shot.

Al-Furqan shocked the world and thrust ISIS upon the stage with a series of videos launched in the summer of 2014. On July 5, 2014, al-Furqan released perhaps its most important video with Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s Khutbah and Jum’ah Prayer in the Grand Mosque of Mosul, a 21-minute video that updated the face of the leader of the terrorist organization that had the world’s attention. Before this video, the image of the mysterious former prisoner was his mug shot.

Weeks later, on August 19, 2014, al-Furqan would shock the world again with the release of A Message to America, a five-minute video that introduced the world to ISIS in a new way—via the murder of James Foley. It ended with threatening the death of another, Steven Sotloff. The video featured a hooded British speaker who was later dubbed by the media “Jihadi John.” This would only be the beginning, though, as a series of beheadings were carried out on video for the world to see.

On September 2, 2014, al-Furqan would release Second Message to America, 2:46 in length, featuring the murder of Steven Sotloff and threatening to kill David Haines. On September 14, 2014, another release appeared titled A Message to the Allies of America, a 2:27 video of the murder of David Haines and the threatening of British citizen Alan Henning. Then on October 4, 2015, the group releases Another Message to America and Its Allies, a one-minute video of the murder of British citizen Alan Henning and the threat to kill American Peter Kassig. This continued with Japanese captives Kenji Goto and Haruna Yukawa in a Message to Japan.

But the group wouldn’t stop there. It was responsible for releasing three other videos that shocked the world. Instead of individual beheadings, a video was released in November 2014 showing the mass execution of Syrian soldiers by beheading. Intelligence officials throughout America and Europe were frantically examining the footage for foreign fighters after a few had been seen in the footage including the Frenchman, Maxime Houchard.

They released the video of the Jordanian pilot Muath al-Kasasbeh, burning alive in a cage in March 2015, which sparked a swift response from Jordan. Weeks later, they released another video with a child soldier killing Israeli Muhammad Musallam with a gunshot through the head. Then they capped off the barbaric series of releases with a double mass execution in Libya of Ethiopian Christians in April 2015. Eventually the videos of beheadings shifted from al-Furqan out to the various regional offices where the savagery of executions would eventually go way beyond beheadings as methods varied from region to region. Al-Furqan set the tone for the regional center savagery.

In September 2016, US forces killed the leader of al-Furqan, a man named Wa’el Adel Hasan Salman al-Fayad, the man who had become so synonymous with the group that he was known as “Abu Muhammad Furqan.” He was at the center of the rise of the most powerful segment of ISIS propaganda before his death by airstrike in his home in Raqqa.

British journalist John Cantilie is a terrorist hostage of ISIS. On numerous occasions he was forced to make videos designed to attack the United Kingdom, the United States, and Western policies. The videos titled Lend Me Your Ears were released through al-Furqan. Two other videos called Inside Mosul and Inside Raqqa were also filmed with Cantilie. He appeared mid-2016 in a brief video released by the AMAQ news agency in 2016.

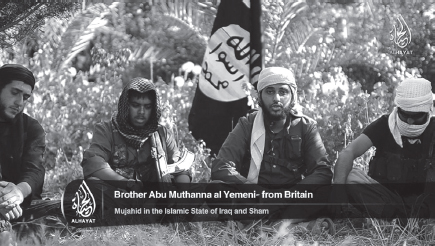

Al-Hayat Videos

In the first video release, There is No Life Without Jihad, released June 19, 2014, Reyaad Khan (a.k.a. Abu Dujana al-Hindi Britain) and other fighters are featured in the English targeted release. The first speaker was Nasser Ahmed Muthana (Abu Muthanna al-Yemeni-al-Britani), followed by Abdul Raqib Amin (a.k.a. Abu Bara’ al-Hindi-al-Britani), Zakaryah Raad (a.k.a. Abu Yahya as-Shami-Australia), Abu Nour al-Iraqi (Australian, damaged left eye), and Neil Prakash.

Al-Hayat was most commonly known because of its non-Arabic titles aimed at the United States, UK, and Europe. It is also responsible for the publication of official nasheeds (religious chants) and the shiny near-quarterly magazine Dabiq.

Figure 47: ISIS video banner. (Source: TAPSTRI)

Taking the Shot—The Role of the Cameraman

To examine how ISIS videos are filmed and produced, testimony from former fighters and media workers of the group who discussed their activities in or in relation to the media center demands has proven the best source. Additionally, numerous videos and photo packages showed the life of ISIS’s “Combat Cameramen.” The media teams often showed the glamorous life of cameramen, editors, nasheed singers, or other media personnel that help put the picture together of how a video or photo story comes to be.

There are videos aimed at the media team; its members look like war correspondents with Sony HandyCams. Running alongside Toyota Helix gunner trucks, the videos show the camera crews putting themselves right in the mix of hot combat to get shots that promote the ISIS image of brave fighting men. There are a couple of videos that give a glimpse of head-mounted cams like the GoPro. The GoPro style footage gives the viewer a “Call of Duty” POV shot usually articulated with the barrel of an AK47 in the view.

The Washington Post conducted interviews for a piece called “Inside the surreal world of the Islamic State’s propaganda machine.” The interviews conducted by Greg Miller and Souad Mekhennet discussed how orders are given and how workers are compartmentalized to create the final video spectacle. They told the stories of several returning fighters who worked with the media machine of ISIS.

In the story of a man they identified as “Abu Hajer al-Maghribi” (who was serving time in Morocco after returning from Syria where he worked with the Raqqa media office), he stated he went through a “month-long program for media operatives” that taught him how to film and edit. He was taught how to sound during interviews.

He stated that he would get his daily video assignments issued to him on paper that bore the seal of “the terrorist group’s media emir” with location and coordinates. He was involved in filming many of ISIS’s more memorable massacres of Syrian troops. He was used to film the British terrorist hostage John Cantilie’s Inside Mosul release. He claims to have used a Canon camera. He was then ordered to transfer the footage to laptops, then to memory sticks before “delivering those to drop sites.”4 The article doesn’t state if he meant a physical or virtual “drop site.” The process was rigorously compartmentalized.

Abu Hajer stated that media operatives are paid more than the average fighter. He claims he was paid $700 per month and free of zakat (taxes).

Another fighter in the Washington Post article under the name “Abu Abdullah” claimed to help arrange dead fighters and other menial tasks. He stated that the media teams control the executions they film. The segments are filmed over and over until the team’s director decides to execute. Off camera a person holds a cue card for the monologue of the executioner or execution leader in the case of mass killings.5

Abu Hajer was one of many who have stated that executions and other video moments are often very staged and the production of the video takes precedence. Harry Sarfo said this highly scripted method broke the illusion of the invincible army once he was asked to essentially perform for a video filmed in Syria.6 In both cases, they also felt a repulsion at the violent and disrespectful killing of other Muslims in a manner that didn’t match what they learned as Muslims.

The camera teams used by ISIS fell into three categories. First Line Video was any footage from Body Cam-, Helmet-, and Weapon-Mounted shots meant to give Point of View (POV). ISIS developed formal Video Support Teams (VSTs) for second line video, which is second person footage of fighters running, shooting, or driving suicide bomb trucks. Finally, the Third Line teams were the Professional News Teams (PNTs) who create the highest quality of propaganda packages. The materials from these teams would be crafted to go directly to the global news media. These segments are often recorded with more advanced lighting, stands, and scripts and were meant to appear newsworthy.

The Video Gear

The product rendered by ISIS would indicate they understand the need to invest in an arsenal of gear to capture their campaign to destroy humanity in high definition. With a mix of GoPro cameras, handheld Sony and Canon cameras, and small project studios used to mix various segments of the spectacle together, the final picture requires quality gear.

According to the Washington Post’s interview with a jailed former ISIS fighter who operated as a cameraman, Abu Hajer, video-making gear and computers came through routes out of Turkey.7 Abu Hajer stated he received gear after his training that included a Samsung Galaxy smartphone and a Canon camera with digital media video recording capability. Videos released by ISIS have shown Sonycams in action in the field.

A new twist on the video recording team efforts was the addition of the Drone Video teams (DVT). By early 2016, the group was using Phantom III aerial drones to record shots including the before, transit, and explosions of suicide bomb truck attacks, as well as to collect intelligence.

Figure 48: Al-Anbar Aerial video footage filmed by ISIS via drone cameras in Wilayat al-Anbar video. (Source: TAPSTRI)

ISIS VIDEO THEMES

Depending on the specific theme, there are repeating formulas for most of the types of releases. There are a handful of themes common in all ISIS videos; some or all of those themes can be combined in a video from time to time.

The Just Will Prevail as It Is Allah’s Will

The largely misunderstood view of execution films from ISIS was that they are portrayed as justice in an eye-for-eye manner where the person being killed is paying for their own crime of betraying the caliphate or paying for the crimes of others as their proxy.

The Grand Betrayal

The leaders of the Arab and Muslim world are often the targets of ISIS scorn. They are accused of working against the interests of Muslims and thus are worthy of being targeted for death. The theme of the grand betrayal constantly repeated by ISIS and other extremist groups is also used as a motivating factor when the recruiters manipulate supporters’ feelings of grievance to encourage them to attack.

There Is Your Enemy

There are so many ways to become the enemy of ISIS if you wait long enough and try hard enough. But to the followers, there was no doubt that the enemy was the one who does not believe in the strict interpretation of the Quran given to them by the Islamic State. This includes not just the filthy unbelievers but the apostate teachers and leaders of the Muslim world. Thrown directly on the screen for all to see, ISIS doesn’t mince words when it labels its enemy. The subject was a driving force in the propaganda in that it makes killing the enemy the preferred way to serve the interest of the caliphate.

The titles of many of the pieces published by ISIS are directed at these targets, as in Harvest of the Spies or Harvest of the Army where dozens of people are propped up for crowds as traitors or dragged off to a ditch and shot and dumped as traitors to the caliphate and thus to Muslims. First, since the majority of these victims are Muslim, they are condemned on the basis of their confession and told that they couldn’t possibly be Muslim (this is called Takfir, or declaring a Muslim a non-Muslim so they can be killed). Thus, they deserve death for working for the apostate regime. In each video of this nature, after the victim is made to confess to a crime of spying or perhaps serving as an Iraqi security official, they are executed as an example and warning to the apostates and unbelievers.

The message isn’t intended just to respond to would-be critics or threats to the caliphate, but to reward those who want to have an enemy that must be punished. In a large quantity of ISIS official videos, there was a crowd drawn to watch the execution of a person who has been condemned by ISIS for crimes. The crowds are mostly eager to watch this macabre spectacle and even cheer on the activities. In one video in which a man was surrounded and killed by a group of people, his executioners piled on and took turns kicking and beating him until he was lifeless. In other cases, witnesses were asked to come in to pull the trigger on blindfolded captives.

Hijra (The Sooner the Better)

One of the key points of change in radicalization occurs during the self-hijra stage. This stage also has a range of graphic and video supplements to encourage this process. By helping viewers to emotionally detach from their friends, family, and surroundings, the cult recruiting of ISIS gives meaning to the transition by reminding the target of this message that the caliphate was thriving, its land is the morally superior place to be and a place where real Muslims find safety to be themselves. Many of the pithy posts that exist on Telegram channels are used to remind ISIS recruits to be “good Muslims” but insist that this means doing what suits the aims of ISIS, including preparing to fight or recruiting friends who may want to fight for the caliphate.

There are stories from the combat outpost (a.k.a. rabat) or front lines that are meant to give you a sense of adventure and a conviction that these fighters are indeed on the “front line” of history in the battle against the unbelievers. In most videos, you cannot see the enemy but simply see fighters rushing forward to enemy positions.

The purpose of these videos was to give the viewer a sense of how victorious the fighters are, so, obviously, there are no videos published that show catastrophic defeat. The video also reproaches the passive viewer for merely sitting there and being a witness and thus not really committing to the cause of protecting Muslims from the evil disbelievers. There was always a subtext of “you should be here doing this” directed at the viewer.

In addition to the fighting videos, the celebration of Eid, religious holidays often marked with feasts, was just one of the lures used to evoke a viewer’s desire to make the journey to Syria. In these selections, the celebrations are made to underline the superiority of the realm of ISIS over other parts of the Muslim world as well as the plight of the disbeliever who couldn’t understand how everyone in the caliphate was so happy.

All Is Great in the Caliphate

The common videos showing ishtishada attacks or Suicide Vehicle-Borne Improvised Explosive Device (SVBIED), a.k.a. suicide truck/car bomb attacks, follow an evolving formula that begins with showing an attacker preparing the vehicle for attack, and his friends wishing him well as he drives in under rocket and gun fire to hit his target, cheered on by the screams of his brothers, God is Great! (“Allau Akbar”). The attacker’s backstory was most often the lead-in, but there are also examples in which the attacker was merely mentioned just before and after the detonation of their vehicle near an outpost berm. One evolution in how these videos have been filmed was the introduction to drones in a few of the regions. Now there was a bird’s-eye view of these attacks in which the same pattern of covering fire from guns and RPGs (Rocket Propelled Grenade) is shown, followed by SVBIED attack. Followed by men with guns rushing in to polish off enemy soldiers.

In some cases, they show stage-by-stage a SVBIED attack with the extended bio and interview with the attacker. Then you see them get into an explosive-filled truck or van that drives off, out of the view of the camera. Cut to the detonation of the vehicle (shown rather dimly in the distance), accompanied by the driver’s fellow fighters back at the original location yelling, “Allau Akbar” in the background. The formula doesn’t change much from the first time we saw these videos a decade before after the release of AQI videos.

But there are some changes worth noting including the use of drone-mounted cameras, which now have shown details of SVBIED attacks from a position that may enable opposition forces viewing that released footage to help predict and prevent such attacks in the future. But ISIS isn’t afraid to use the drones for video now and has done so with videos of drones operating out of what’s presently its most strongly held regions of Aleppo, Raqqa, and Mosul.

The End Times Scenario

One of the key distinctions between ISIS and other extremist groups was how its message was truly apocalyptic. The result is a mission focused on the advancing toward end times as the great showdown of good and evil that will come. There are endless references to this grand showdown in videos, photo shows, pamphlets, and the magazine that bears the name Dabiq, the presence of the Dijjal (false messiah).

THE PRESENTATION

Much has been said about the visual quality of ISIS videos, especially the misappropriated phrase “Hollywood-style” to describe the High Definition footage mixed with HD presentations cooked up by the graphics teams and tied together with a limited narrative that sometimes may resemble a PBS special on Islamic history. There was typically a patient and steady narrative voiceover in many videos. As if produced for a historical documentary segment, many of the titles engage in large narratives that end with attempting to justify ISIS actions before turning to running GoPro filmed footage and the steady main camera shots of an execution. The techniques used to piece these mininarratives together can be applied on laptops and PCs with off-the-shelf video gear easily smuggled into the ISIS territories through routes in Turkey, according to former fighters.

The HD-level images are produced with a variety of cameras including GoPros strapped to the attackers’ heads or bodies, run along cameramen using Sony handheld cameras and in some cases cell phone cameras. Other captive fighters who reported that they have worked in the media centers reported that they have used Canon cameras for their assignments. ISIS was keenly aware that the world takes them more seriously because they bring forward terror in high definition.

THE MEME MACHINE

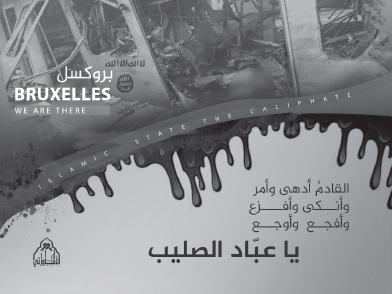

For every event that could relate to ISIS culture there was a meme that will be rendered within minutes. The message of “You’re next” after the attack on Paris was sent to Telegram channels in GIMP- or Photoshop-produced panels; the same threats were circulating within hours of the attack in Nice. Then came the images aimed at Germany that indicated it would be facing lone wolf attacks soon. Within a week after Nice came an axe attack in Wuerzburg, Germany, in the name of ISIS by Afghan teenager Riaz Khan Ahmadzai, and within two weeks Syrian Mohammad Daleel killed himself with a backpack bomb filled with nails and metal debris in Ansbach, Germany. Within hours of their respective attacks were celebrity-styled memes celebrating their attacks and taunting the government’s inability to protect citizens from these attacks.

Figure 49: ISIS meme cards published on Telegram by Aswirti media. (Source: TAPSTRI)

Once the theme starts, you can expect to see it a few times before it shifts. Often the group is focused on prodding a leader or a country when things are going badly. If diplomatic missions fail, hurricanes strike, or elections get ugly, the ISIS supporters would be there to fill in the space with ridicule.

When the al-Qaeda affiliate in Syria, Jabhat al-Nusra, decided to break off official relations with the international terror group, ISIS supporters took to the web to poke at Jabhat al-Nusra’s leader with a picture meant to insult him.

Figure 50: ISIS fanboys on Telegram poke fun at the Jabhat al-Nusra leader in graphic. (Source: TAPSTRI)

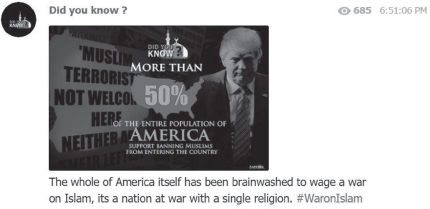

One channel that appeared on Telegram in support of ISIS posted graphics of facts about Muslim history under the header “Did you know?” The series was used to not only praise famous Muslims, but to denigrate critics like Malala Yousifzai and also to feature the anti-Muslim ban called for by a candidate for President of the United States.

Figure 51: Telegram entry on the Did You Know? page. (Source: TAPSTRI)

THE ONLINE PHOTO SETS

Almost daily, ISIS regional offices released photo packets to frame the fight for the regions they oversee with all photos showing victorious fighting, productive services, and the dedication of ISIS members. The photo sets vary in number but are a daily snapshot from the view intended to convince the members all is great in the caliphate.

There are some photo sets that are simply nature shots, pictures of a clear moon, or vibrant greenhouses. These photos are perhaps the most important to convince followers that ISIA is creating a utopian society, one that is stable, productive, resilient, and healthy.

Like the video releases, the photo sets are loaded with grievance. It was a strong theme in many photos that are filled with destroyed buildings and injured civilians, especially children. The images are released with tag lines that blame either coalition forces in many cases, or the Russians and Assad’s forces.

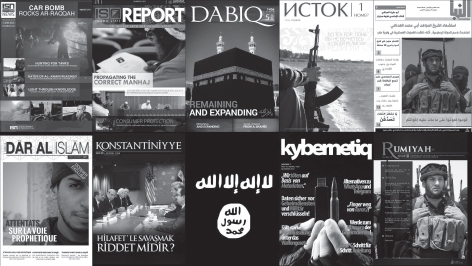

In the lead-up months to the announcement of the return of a caliphate, ISIS was putting together two magazines called the Islamic State News and the Islamic State Report. They were released starting in late May and early June of 2014 before the announcement of Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi as the Caliph. Then came the magazine that became synonymous with ISIS, Dabiq. The apocalyptic title conveyed the primary goal of the organization, a showdown with the army of the kufar on the lands in Syria.

Figure 52: Magazine montage. (Source: TAPSTRI)

To get the word out, the organization would need to reach the other regions with titles and articles that concern them, and the al-Hayat Media Center was the place to do it. Working out of a two-story house in Raqqa, those producing the magazines ensured they measured up to the quality and precision found in the finest article-friendly magazines. Like the AQAP magazine, Inspire, these publications gave a professionally packaged and attractive presentation of the beliefs and actions of a regime devoted to killing lots of people.

Packed with features on regional reports, ongoing religious arguments against other rival groups, or profiles and interviews of the favorite ISIS fighters and leaders, the magazines are glossy and well produced yet vary in their release schedules.

The “unbelievers and apostates” eagerly anticipate and read them for the morsels of intelligence they may provide, but months can go by between editions. Some editions may have revealed more personal information on targets like Jihadi John or the Paris attacker, Abdelhamid Abaaoud. After the Paris attacks of November 2015, most of the attackers were featured in a video and a poster in Dabiq.

Figure 53: Dabiq magazine. (Source: TAPSTRI) ]

Dabiq—English Publication

With its high-definition photos presented in high-quality magazine layout, Dabiq is proof that the message from its true publisher, ISIS, was serious. The themes inside each edition projected what ISIS officials want the world to believe about the organization by running features on new alliances, expanded operations, philosophical explanations of its mission, clear condemnation of enemies, and promos for the latest video releases. One edition even had hostage information (Dabiq 11) in full-page “ads” at the end of the publication.

The number of pages in each edition can run from as few as 40 (Fifth Edition) to as many as 83 (Seventh Edition). There seems to be little concern about this variation.

Dabiq runs a section every month that features an Enemy Number One of the Islamic State. The column “In The Words of The Enemy” has appeared in every edition. The first piece was “The Return to the Khilafah.” In that initial piece, Col. Douglas A. Ollivant, the former Director for Iraq at the National Security Council, was featured. Edition #15 featured Pope Francis and Grand Imam of al-Azhar, Ahmed Muhammad Ahmed el-Tayeb.

Here is the list of the first fifteen Enemies of the State:

In The Words of the Enemy

• Douglas Ollivant—Edition 1

• John McCain—Edition 2

• Barack Obama—Edition 3

• Chuck Hagel—Edition 4—Revisited 6

• Andrew Liepman—Edition 5

• Benjamin Netanyahu—Edition 6

• Patrick Cockburn—Edition 7

• Rick Santorum—Edition 8

Gary Berntsen—Edition 8

Richard Black—Edition 8

• McCain and Lindsey Graham—Edition 9

• Rami Abdulrahman—Edition 10

Ahmed Rashid—Edition 10

Yaroslav Trofimov—Edition 10

• Michael Scheuer—Edition 11

• Abu Firas as-Suri, Jabhat al-Nusra spokesman—Edition 12

• Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani, Qatari Emir, Erdegon—Edition 12

• Michael Morell—Crusader-Edition 13

• Ban Ki Moon—Edition 14

• Pope Francis-Ahmed el-Tayeb—Edition 15

Figure 54: Dar al-Islam. (Source: TAPSTRI)

Dar al-Islam—French Publication

With nine editions published by 2016, the Dar al-Islam magazine was focused at the French-speaking audience. In comparison to Dabiq, the Dar al-Islam was started as a shorter magazine, but it expanded steadily from 16 pages in the first edition to 114 in the eighth edition.

Figure 55: Konstantiniyye. (Source: TAPSTRI)

Konstantiniyye—Turkish Publication

For the Turkish audience, al-Hayat has the Konstantiniyye magazine. Published in Turkish, the magazine is filled with some overlapping themes from Dabiq publications but often with the focus on the secular society of the neighbor to the north. Attacks on Turkey’s relationship with Russia, Europe, or the United States are always fodder for the magazine.

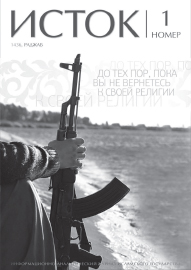

Figure 56: Istok. (Source: TAPSTRI)

With the long-standing jihadist fight against the renowned atheist state to its north, ISIS started publishing a magazine aimed at the Russian-speaking audience. The content of the four releases before September 2016 was largely Russian reprints of Dabiq content aimed at Chechnya and other former Soviet countries. ISIS has largely relied upon the Furat media group to handle translations of videos and texts for the Russian audience.

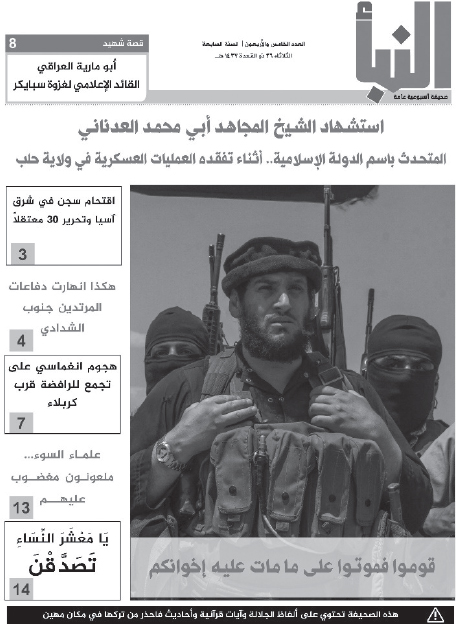

Figure 57: An-Naba. (Source: TAPSTRI)

An-Naba—Arabic Publication

The “Weekly Newsletter” features the latest ISIS attacks and campaigns, with text accompanied by a few images. It is printed, published, and widely distributed in the areas controlled by ISIS.

Figure 58: Kybernetiq. (Source: TAPSTRI)

Kybernetiq—German Publication

This ISIS-affiliated German language magazine was focused on the cyber jihad and was released December 2015; it is focused on encryption, metadata, and apps, including a look at the features of the encryption app Asrar al-Mujahideen, otherwise known as Mujahedeen Secrets. Only one edition had been released by September 2016.

Figure 59: Rumiyah. (Source: TAPSTRI)

Virtually identical in content to Dabiq, a new magazine was launched by ISIS in September 2016 with essentially the same content. It seemed to be hastily slapped together, possibly because the news of Abu Muhammad al-Adnani’s death had come only days before the on-press date. The articles in the first edition were a mix of criticisms aimed at those on the typical enemies list—Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, Abu Muhammad Al-Maqdisi, the mentor to Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, et al. It even featured a lone wolf threat directed at a random florist in Manchester, England, Stephen Leyland, with a picture of him smiling at work in his shop to show their reach could touch even those at a low level.8

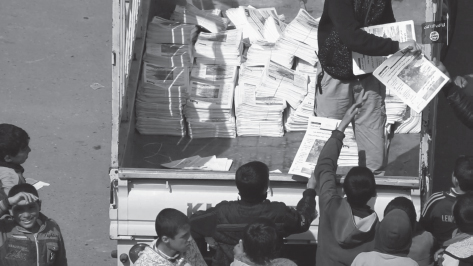

Figure 60: Iraqis gather to grab a copy of the latest an-Naba weekly newsletter. (Source: TAPSTRI)

THE NASHEED CHANTS

Every movement, revolution, or generation needs a soundtrack. In the background of the majority of ISIS videos are the nasheeds or the anasheed jihadiya—Gergorian chant-like songs about fighting for the caliphate. The themes are simple and symbolic tributes to dead fighters, celebrating successful campaigns or singing the praise of someone like al-Baghdadi or Osama Bin Laden. But despite the strong association of these simple redundant melodies with ISIS, nasheeds have been around for many battles across decades. As required by strict Sunni fundamentalists, there are no instruments used in ISIS nasheeds. However, other groups have used musical instruments to accompany the singers. It was clear that ISIS uses Auto-Tune on its vocal tracks, and there was one official wilayat video that shows a nasheed singer multitracking the song with a dynamic cardioid microphone and small recorder connected to a laptop.

ISIS has used nasheeds in its recruiting and inspirational efforts for current fighters. Ajnad Media was founded in August 2013 to focus on nasheed and surah (chapters from the Quran) readings. Simple and repeating lyrics that are easily internalized, they produce an almost hypnotic effect upon the listener. Mixed with Quranic allusion. In addition to Arabic, they have been released in other languages including English, German, Chinese, Bengali, Bosnian, Pashtu, Turkish, Urdu, and several in French. For example, their greatest hit “Clashing of the Swords” was released in June 2014 during the seizure of Mosul and Raqqa:

Clashing of the swords: a nasheed of the reluctant.

The path of fighting is the path of life.

So amidst an assault, tyranny is destroyed.

And concealment of the voice results in the beauty of the echo.

By it my religion is glorified, and tyranny is laid low.

So, oh my people, awake on the path of the brave.

For either being alive delights leaders, or being dead vexes the enemy.

So arise, brother, get up on the path of salvation,

So we may march together, resist the aggressors,

Raise our glory, and raise the foreheads

That have refused to bow before any besides God.

The banner has called us,

To brighten the path of destiny,

To wage war on the enemy.

Whosoever among us dies, in sacrifice for defense,

Will enjoy eternity in Paradise. Mourning will depart.

While other groups, including, al-Qaeda, create nasheeds, the overt integration of nasheeds into ISIS videos has had a powerful effect. Behnam Said, who has dedicated his PhD research to studying nasheeds, said that the use of nasheeds dates back to the late 1970s during the “Islamic resurrection.”

Figure 61: Al-Hayat video featuring British citizens appealing for fighters to join them in Syria. (Source: TAPSTRI)

THE TERROR SHOCK VALUE VIDEOS

Perhaps the thing ISIS was best known for was its publication of execution videos, including the murders of James Foley, Steven Sotloff, David Haines, Alan Henning, Peter Kassig, Kenji Goto, and Haruna Yukawa. There have also been other execution videos that featured Syrian fighters and Egyptian Coptic Christians who were executed en masse.

This modern macabre spectacle has its video roots in the beheading of a Russian soldier in Chechnya. The first American beheaded on video was Daniel Pearl. Al-Qaeda beheaded Pearl in 2002. He was forced to read a series of grievances. Demands included release of all prisoners held at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, return of Pakistani prisoners to Pakistan, the end of US activities in Pakistan, and “The delivery of F-16 planes Pakistan paid for and never received.”

The first video of an American being beheaded by al-Qaeda in Iraq was released in May 7, 2004. Nick Berg’s murder was blamed on the abuses at Abu Ghraib. It was later uploaded to the Muntada al-Ansar website and given the title Abu Musab al-Zarqawi shown slaughtering an American. The “Acme Commerce Sdn Bhd” web-hosting company in Malaysia that hosted the website took it down.9 The Zarqawi propaganda model under Tawid wal-Jihad began with Nick Berg and continued with others including Kim Sun-il, Bulgarian Georgi Lazov, Durmus Kumdereli, Eugene Armstrong, Jack Hensley, Kenneth Bigley, and Shosei Koda.

A decade passed between the Zarqawi era of blood and gore and the rise of ISIS. Zarqawi was killed June 7, 2006, and with his death a change in the leadership over to Abu Ayyub al-Masri and a scramble for reaffirming the message. As Zarqawi’s group morphed through its various incarnations from AQI to ISIS, the videos were still being made, but just not disseminated globally. That would change with the seizure of a third of Iraq and half of Syria in 2014.

The first major video, as noted previously, was released on August 19, 2014 with A Message to America. It opens with a statement of grievances. The text stated, “Obama authorizes military operations against the Islamic State, effectively placing America upon a slippery slope towards a new war front against Muslims.” After a segment with Obama discussing airstrikes, James Foley was presented in what has been compared to GITMO orange clothing alongside an executioner clad in black who was armed with both a gun and a knife. Foley speaks first as he’s forced to read a statement blaming America and his own brother for his death. The unnamed executioner then addresses some remarks to President Obama about US airstrikes and efforts to remove ISIS from Iraq and Syria.

In what was a first for the United States, the video ends with an edited but real beheading of James Foley followed by a threat against Steven Joel Sotloff. The executioner closes with, “The life of this American citizen Obama depends on your next decision.” The video was uploaded to YouTube, Liveleak, and other video-sharing sites. Take-downs followed but the damage was done. The era of beheading videos had begun.

This pattern of release continued on September 2, 2014, when the next video, A Second Message to America, came, featuring Steven Sotloff. At a length of only 02:46, it was more direct. Again, ISIS began with Obama comments about continuing the military campaign against ISIS. Then came a forced reading by Steven Sotloff aimed at President Obama to withdraw troops. The video ends with the beheading of Sotloff in the same edited manner as the Foley video. Then the masked executioner from the first video threatens the UK with the murder of David Cawthorne Haines.

On January 3, 2015, the world was locked in horror as ISIS moved from beheading its victims to the execution of Jordanian pilot Muath al-Kasasbeh. Kasasbeh had been captured, and for weeks there were negotiations through backdoor channels to try to secure his release. However, he was murdered by the Islamic State and the film was released showing the terror group burning him alive in a cage. The reaction by Jordan was swift. They not only conducted airstrikes, but executed a captive who was highly sought-after by ISIS in the swap, an Iraqi woman named Sajida al-Rishawi who had been facing the death penalty for her role in a 2005 bombing that killed 60 people.

Over the next couple of years, any doubts about whether ISIS fighters were really beheading people were dispelled as ISIS increasingly made the murders more graphic by doing things like speeding up the camera rate to create up-close slow-motion execution shots.

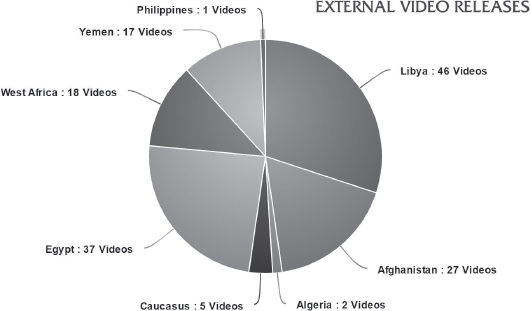

The primary substates or wilayat are in Syria and Iraq, where decisions are closely coordinated with the central authority. Each of these media offices specializes in creating ISIS media for their region but also may perform a function for the entire organization. Wilayat Sinai and Wilayat Janoub have been responsible publishing metrics of the caliphate’s attacks and resources.

Then there are the external wilayat found in Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Afghanistan, and parts of the Caucasus regions including Chechnya and Dagestan. The features of the area, the battles with other locals will alter the composition of each region’s final product. For example, in Yemen, the videos will highlight battles with the Houthis and AQAP. The Iraqi videos will focus on clashes with Iraqi security and Kurdish forces. Syria will focus on Assad forces, Kurds, and Turkey to the north.

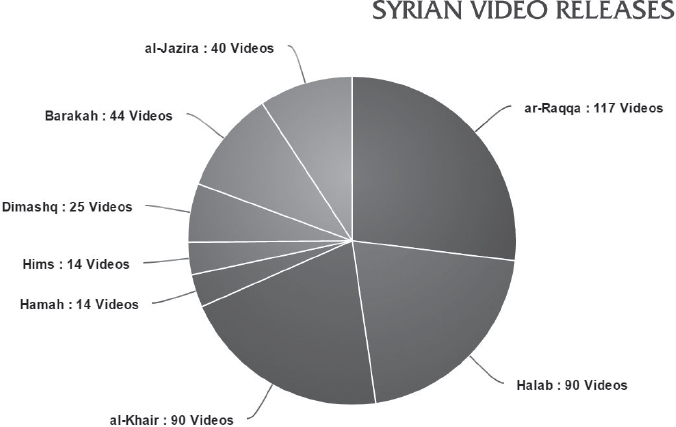

To give a sense of how many titles have been released by ISIS official wilayat media offices, by August 1, 2016 here are the release numbers per wilayat:

Figure 62: Syrian Video Releases. (Source: TAPSTRI)

AS OF AUGUST 1, 2016, TOTAL VIDEO RELEASES PER REGION. (SOURCE: TAPSTRI)

Syria wilayat

Raqqa 117, Halab 90, al-Khair 90, Hamah 14, Hims 58, Dimashq 25, Barakah 44, al-Jazira 40

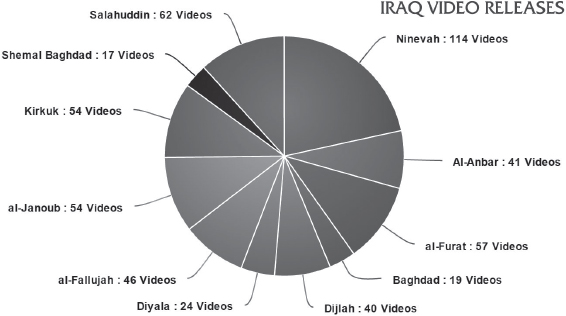

Figure 63: Iraq Video Releases. (Source: TAPSTRI)

Iraq wilayat

Nineveh 114, Al-Anbar 41, al-Furat 57, Baghdad 19, Dijlah 40, Diyala 24, al-Fallujah 46, al-Janoub 54, Kirkuk 54, Shemal Baghdad 17, Salahuddin 62

Figure 64: External Video Releases. (Source: TAPSTRI)

Libya 46 (Barqa 22, Tarabulus 24), Egypt 37, Afghanistan 27, West Africa 18, Yemen 17 (Aden 3, Hadramaut 5, Sana’a 4, Shabwa 5), Caucasus 5, Algeria 2, Philippines 1

AFFILIATED MEDIA AGENCIES

There are dozens of nonofficial media groups that reedit existing ISIS material to recycle the message but are not sanctioned by ISIS. ISIS has specified what are its official centers in both video and printed materials. Some of the groups include “al-Battar,” “al-Nusra al-Shameya Media,” “Al-Yaqeen Media Center,”“Asawirti Media,” “Grandchildren of Aisha,” “al-Samoud Foundation,” and a group called “The Constancy.” In many cases, the video quality released by these groups was significantly lower and some almost un viewable because retread video was taken from other videos that had been highly compressed for the web or had audio levels that were too high, too low, or muffled.

A group was formed of many of these unofficial media houses under the banner “Al-Jabhah al-I’ilamiya li-Nusrat al-Dawlah al-Islamiyah” or the “The Media Front for Support to the Islamic State.” This group would do what other ISIS media groups including al-Battar, Al-Ghuraba, Markaz al-Aisha, Al-Wafa, al-Minhaj, al-Wagha media, and Rabitat al-Ansar would do.

THE PROPAGANDA MACHINE IN MOTION

We can see that the early incarnation of ISIS known as al-Qaeda in Iraq or AQI was intent on spreading its terror via video and that early on al-Qaeda objected to these images for fear that they would be used against the effort to gain recruits and defeat the American, European, or Israeli interests. Instead, AQI was over the top because of its beheading videos under Abu Musab al-Zarqawi.

In order to remind followers that they have a role to play in getting the message out, ISIS media leaders tell them to propagate widely and makes distinctions mainly between inside and outside channels. For the insiders, there are reminders of their duty to remain pious Muslims, serve the caliphate, and avoid being lazy. There was the occasional instruction to share links to like-minded cult members.

The Media Pitch

Islamic State supporters online have exceeded tens of thousands. However, a great number of them only watch video releases and follow the news.

To those, I send this message: Supporting brother, you are a part of the Islamic State media on the Internet; don’t be a liability by just watching videos and following only, but learn how to upload, share, transcript, translate, program and work towards having an impact on the ongoing war against the disbelieving Crusaders.

Just as a society, Islamic State supporters include very diverse people with different skills and abilities; use what you now to do best to support the Islamic State. If you don’t, learn how to download/upload releases, get the know-how from an efficient supporter.

Ask yourself, what have you done to support the Islamic [State]? Are you here to effectively support the Khilafah or to spend your free time? Supporting the Islamic State is by work, not by sitting watching idly. Leave the laziness of excuses and ask yourself what can you do to support the Mujahideen who defend the honor of the Muslims, facing the nations of Kufr and disbelief, giving their blood in battles in the east and the west?

Stand up, dear brother, and learn new skills, this is an obligation upon you now that all the nations of Kufr have stood together to face the Islamic State—may Allah give it glory—and be a thorn in the throats of the disbelievers. Share the truth about the Islamic State to the Muslims. How many Muslims have been guided and saw the reality of this war thanks to Allah then to a video release, a picture report, and article or just a tweet from an Islamic State supporter?

It’s our duty dear brother, put your trust in Allah, take the necessary online precautions and support the Mujahideen with everything you can.

Translated from Arabic by Maghrebi Witness —MW

Like many messages from ISIS, the aim of this message was to be spread widely.

The Propagation Channels

Figure 66: Khilafah News banner. (Source: TAPSTRI)

Khilafah News

Fed by official headlines from around the caliphate, Khilafah Internet News shares the daily lists of attacks, excerpts from speeches by leaders, or other headlines created by the actions of ISIS leaders. Khilafah news was often found on posting sites like JustPasteIt and on Telegram.

Figure 67: Telegram advertisement of Nashir’s new Portuguese channel from ISIS. (SOURCE: TAPSTRI)

NASHIR Telegram Channel

This channel posts photo slide shows, official ISIS announcements, and link clusters to the latest official ISIS videos. Unlike several other channels, it does not engage in propagating links for unofficial sources or the various echo chamber videos. It will also publish the links to the latest official ISIS print media like an-Naba, Dabiq, or other releases.

When the channel announced it would start broadcasting in Portuguese, there were analysts who took this to mean that ISIS had established a foothold in Brazil. The concerns were largely tied to security concerns around the Summer 2016 games in Rio. The games were completely without incident.

Figure 68: Al-Bayan Telegram advertisement from ISIS. (Source: TAPSTRI)

Al-Bayan Radio

Daily dispatches from events in the ISIS region and with occasional announcements from across the world. Releases are featured as mp3s along with .doc and .pdf releases of the headlines in both Arabic and English. The outlet has also been featured in short-lived website form as both stand-alone domain and as a wordpress.com page.

Figure 69: AMAQ Agency Telegram advertisement from ISIS. (Source: TAPSTRI)

Amaq News Agency

Amaq News Agency is the source that was almost synonymous with ISIS claims of responsibility even though it is not listed by ISIS as an official agency. Though never listed in the official centers under ISIS, it acts more in conjunction with ISIS than any other satellite organization. Though little is known about its staff or hierarchy, it was revealed after his death that ISIS minister of information and head of al-Furqan media, Wa’el Adel Hasan Salman al-Fayad, was a board member of Amaq. Despite this, al-Furqan’s video The Structure of the Khilafah did not list Amaq despite listing al-Bayan (radio), an-Naba (newsletter), Ajnad (nasheeds, sermons), Al-Hayat (non-Arabic publications), and Maktabat al-Himmah (print publications).

The group films and photographs events in the same manner as normal news agencies around the world, but with ISIS pointing the finger at the Assad regime, the coalition forces, and the various militias who are fighting ISIS in Syria and Iraq.

Amaq News Agency ran several Telegram channels in English and Arabic. They developed their own news feed app for Android phones.

In the early days of jihadist media, the communication and propaganda was disseminated via cassettes, VHS, or Hi8 tapes. Eventually that gave way to digital media like CDs, DVDs, jump drives, and smart cards. AQI Spokesperson for Zarqawi, Abu Maysara al-Iraqi, used YouSendIt to send files after running into perpetual issues at the time with file hosting on free pages like Yahoo.10

The materials are introduced to the web via uploads to any number of these dead drop sites, or sites intended to dump data anonymously, and now also via Telegram downloads. Once on the web, the messages on Twitter and Telegram often post links to a dozen or so sites that are file sharing-related and the “official” version uploaded to Archive.org. For a while, Archive.org was rather slow to take the clips down, but by mid-2016 they were becoming very effective in responding with file deletion of audio-video material from ISIS sources. In some cases, videos would be posted and within two hours or less it was a dead link at Archive.org and/or YouTube. By then, Twitter and Telegram messages that contained these links would be useless.

But there are occasional stand-alone pro-ISIS media archive sites that migrate frequently around the web. These outlets keep up with the video releases. Though they are becoming less common, they are still published occasionally on Telegram channels. By 2016, the most common means of finding ISIS videos would be Telegram. All day long there are download links published and direct links for getting the file via channels on the social media platform.

The Modern Day “Digital” Dead-Drop

In literature and life, spies used to have rocks, boxes, and other strange locations to do “dead-drops,”an old intelligence term for a place where items such as a film minicassette and money could be left without the agent waiting around to be discovered. But for the modern-day terrorist, Internet pasting pages are the prime location used to send files, save files, or otherwise share data with conspirators without hassle—digital dead-drops. The terrorists before YouTube had to come up with a way to share videos. Abu Maysara al-Iraqi was one of the first to simply go to YouSendIt to share files with AQI supporters.11

Some of the sites used by ISIS in the first few years include JustPaste.it, Google Drives, YouTube, Cloud.mail.ru, Dailymotion.com, Archive.org, My.mail.ru, Sendvid.com, Userscloud.com, and Samaup.com.

Using these sites, the followers fill up repeaters of the original file, making it harder to eliminate the files from the web. In some cases, ISIS users have coordinated all the ISIS videos into files with the material organized and categorized by wilayat and release numbers. Other sites like TimesOfIS.wordpress.com maintained a running chronology that was reliably updated for months until it was deleted by Wordpress in May 2016. In other cases, sites like ISdarat variations on Wordpress kept track of affiliated releases from al-Battar, al-Samoud, and al-Waad in addition to Amaq and official ISIS media channels.

Distribution on Telegram

In Telegram, you may run across channels that are available to read or “join” without hindrance, but most of the important channels are set to privacy after an initial period of announcement. Posts flow all day with links to other ISIS forums, postings that you have to watch continuously or miss your way in for another day. If you’re trying to follow Amaq News Agency, for instance, your access to the channel can last anywhere from a few minutes to a couple of hours before you get “Error-The Invite link is invalid. Technical details here.”

The channels of ISIS and AQ material on Telegram have a range of subjects that break down into General news about the caliphate (internal and external), Publications (the latest video, slide show, pamphlet, or magazine), Rebroadcasters (users who only recycle other’s postings), Graphics or How To Channels, Operations channels (Online Da’wah Operations, CCA), and of course plenty of cult-level obsession with the passages and interpretations of the Quran. There’s even a snarky channel mentioned earlier called “Did you know?” that loves to point out bits from Islamic history to show how uninformed or ignorant the disbelievers can be. “Did you know that Jack Sparrow is really Yusuf Reis?” one says as it seeks to show how Hollywood and American pop culture doesn’t, namely, that these figures came from Islamic culture.

Another channel, al-Nusra al-Shameya, spent months posting how-to graphic instructions so you can learn how to cut out horses, fighters, and other figures from the video stream and make your own shiny ISIS video graphic. The tools would be easy-to-use graphic apps, which are often included.

Rely on the News Echo Chamber

ISIS was well aware of how to use the news cycles as their predecessors had before them. Well-timed manipulation of video releases, audio releases, magazines, and other materials keep journalists, analysts, and counterterrorist analysts waiting for the next bit of information. This game continued under ISIS.

When Kim Sun-il was killed in June 2002, Jama’at al-Tawid sent a video tape of his execution to al-Jazeera, which injected the story into the news cycle. Earned media was free media because the shock value of ISIS media content was effective in getting the attention of and a free echo from news outlets, officials, and the chattering class. Point made?

For instance, after the execution of Bulgarian citizen Georgi Lazov, Zarqawi’s group, Tawhid wal Jihad, posted a statement, “Await for a video with the execution of the Bulgarian unbeliever” and a single photograph of a fighter holding a severed head.12

In June 2016, a release from al-Furqan had counterterror analysts locked to their Telegram and Twitter feeds as they waited to hear an audio clip from Abu Muhamad al-Adnani that called for attacks during Ramadan. The guessing game went on for hours to the point where ISIS followers in Telegram and Twitter channels were laughing at the analysts with eager anticipation. When the audio finally came down and the watching and waiting had yielded a disappointing result—it wasn’t a message from al-Baghdadi. Many had believed it would be because it was supposed to come via al-Furqan.

THE BATTLE OF THE #HASHTAGS

The caliphate followers are strong proponents of the use of hashtags and extensively use various tags to promote their latest campaigns. The choice of tag depends largely on the aim of either promoting a message or mocking (trolling) a message. Many times when looking for a new video release you could go to Twitter and type in something like #alfurqan, or if you could read Arabic you could follow the hashtags associated with ISIS channels more directly by following tags that were very topical or referred to regional clashes in Syria, Iraq, or Yemen.

The primary tags associated with ISIS have been #IslamicState and #ISIS. There are times where the tag was aimed at followers like #WeAllGiveBayahToKhilafah from late August 2015.

Sometimes the tag was intended as psychological warfare, like the hashtag that was aimed at the United States during Steven Sotloff’s captivity. In one example, there was a picture made with President Obama superimposed over Jihadi John with the phrase, “Why Would I Care about Him,” and the hashtag #StevensHeadInObamasHands.13

Hijacking Trending Tags

As terror tragedies associated with ISIS hit the news, its followers began to flood posts about reactions throughout the world. Tags like #prayfornice or #orlandoshooting became ripe for trolling by ISIS fanboys to the irritation of those still in shock over the attacks. It didn’t take long after the attack in Nice, France, for ISIS Telegram channels to begin encouraging mocking (trolling) hashtags reflecting the tragedy. While trolling, their members could not only excite the hatred against the group, but discern where they had sympathy or potential recruits.

The group also often attacks random targets in order to get attention, instill fear, or both. In January 2016, ISIS fanboys attempted to hijack #JustinBieber with a banner for an execution video.

One group that regularly invades hashtags is the Online Dawah campaign; it is the almost official troll brigade online. With a Telegram channel in hand, they set their daily aims on pages with comment sections in order to harass participants, Muslim and unbeliever alike.

Made Ya Look

ISIS took their method of getting the world’s attention up a notch in the late spring of 2016. On a Saturday morning in May of 2016, notification went out that there was a new al-Furqan release coming soon. With a technique as simple as advertising an upcoming release, ISIS via al-Furqan demonstrated that it was able to capture the attention of the analyst and law enforcement world in a long waiting game played out on that Saturday in May. First, al-Furqan released a “coming soon” banner then followed it in multiple languages across multiple platforms and channels including Telegram and Twitter. Analysts were guessing at what the content would be for hours. Was it a claim of responsibility for the missing Egypt Airbus? Was it going to be al-Baghdadi?

Figure 70: That They Live by Proof banner. (Source: TAPSTRI)

The hashtag #alfurqan started trending—being widely picked up on by Internet users—but by late morning found that what had been so keenly anticipated was merely an audio message from al-Adnani called “That They Live by Proof” calling for ISIS followers to launch attacks wherever they happened to be in the name of ISIS. There had been great hope that the release would be a claim of responsibility for the downing of EgyptAir MS804. A month later, the same hashtag would be used to advertise al-Furqan’s video The Structure of the Khilafah, a presentation aimed at demonstrating that it was a vibrant state.

But the battle wasn’t one-sided, as the hashtags #DefeatingDaesh and others were in play. Counterefforts were often given hashtags including #khawarij, a term the terror group particularly did not like.

#AllEyesOnISIS

Launched by Twitter handle @Ansaar999, this hashtag was dubbed the source of an ISIS “Twitter Storm” in late June 2014 as ISIS swept across Iraq and Syria, declaring the founding of a caliphate at the end of the same month. Seemingly from all over the world, followers were posting pictures of their locations and stating they were supporting the caliphate. Yet many of these photos had been previously published months earlier and were unrelated to the upcoming “Twitter Storm.” One from @ahmetmatar11 (featuring a still of al-Bilawi) had a picture of pink cupcakes topped with ISIS flags and a flag in the background with “Support from South Africa” in the tweet.

In a way, #hashtags are very representative of what makes groups like #ISIS hard to defeat. You can eliminate the @users, but the hashtag theme (#idea) has taken shape in a manner that was harder to knock down.

THE SHIFTING LANDSCAPE

As the technology shifts, we can expect to see the methods of creation, dissemination, and the medium of delivery change. We can also expect to see a change in the emphasis as conditions on the ground for ISIS change. At the time of this writing news just broke from Syria of the death of Abu Muhammad al-Adnani, who was highly involved in the media campaigns.

Additionally, there are few notable anti-ISIS media campaigns undertaken to challenge the propaganda coming from the voices of ISIS, official or unofficial alike. The lack of substantial pushback to their message emboldens their voice. The only notable anti-ISIS media, ironically, come from al-Qaeda and AQ affiliates like Jabhat Al-Nusra, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, and al-Qaeda in the Maghreb. There are Muftis and clerics who have challenged ISIS, but there have been no notable campaigns to get their message out to the masses in a manner that compares to the propaganda onslaught of ISIS.