The Anti-ISIS Cyber Army

Who is standing up to ISIS online? A coalition of governments, a coalition of private enterprises, and a range of private individuals who have, like cyber vigilantes, taken on an effort to eradicate ISIS from the Internet. The United States Government’s efforts via the Pentagon, State Department, and intelligence and law enforcement agencies are constantly being tested, since terrorist sometimes stay a step ahead.

There the little consensus on how to balance public safety and the assumed right to privacy online. Government has a duty to protect its citizens. Private enterprise tech firms have a commercial goal that was undermined by the presence online and association with bad actors of any kind. Private citizens who are skilled in using the tools of the Internet have mounted take-down efforts against the ISIS media materials and channels.

THE UNITED STATES EFFORT AGAINST ISIS ONLINE

The Pentagon and the State Department have active campaigns to confront online recruiting and terrorist or criminal operational use of the Internet. Congress’s efforts have been limited, since it remains in perpetual deadlock. The White House has used its influence and power to call on tech leaders for input about what can be done to combat the online presence of ISIS. During the 2016 elections, the presidential candidates called for a declared cyber war against ISIS.1

The House of Representatives

In December 2015, the Combat Terrorist Use of Social Media Act (H.R.3654) was passed by the U.S. House of Representatives. It requires the President to submit a strategy to congress within 180 days of enactment that will serve counterterrorism efforts on social media. The key provisions include:

• “an evaluation of the role social media plays in radicalization in the United States and elsewhere;

• an analysis of how terrorists and terrorist organizations are using social media;

• recommendations to improve the federal government’s efforts to disrupt and counter the use of social media by terrorists and terrorist organizations;

• an analysis of how social media is being used for counterradicalization and counterpropaganda purposes, irrespective of whether such efforts are made by the federal government;

• an assessment of the value to law enforcement of terrorists’ social media posts; and

• an overview of training available to law enforcement and intelligence personnel to combat terrorists’ use of social media and recommendations for improving or expanding existing training opportunities.”

The US Senate

In July 2016, the US Senate Homeland Security Committee passed S. 2517-Combat Terrorist Use of Social Media Act of 2016, a companion bill to H.R. 3654.

On July 11, 2016, the US Senate Homeland Security Committee passed S.2418-The Countering Online Recruitment of Violent Extremist Act. This act expands the resources for DHS in order to develop programs to counterterrorism including how to counter the propaganda used for recruitment, creating alternatives for those who are potential recruits. “If we can shut down their communications, they cannot radicalize people to conduct terror attacks like what we saw in San Bernardino,” says Representative Michael McCaul.2

The battle to find the right balance in the law, law enforcement, civil liberties, and private enterprise continues to be active and quite dynamic. Many governments are enforcing blocks on end-to-end encrypted technology or in other cases banning use of Virtual Private Network (VPN), an internal network that acts like a closed loop of communication. There are many areas where the demands of law enforcement conflict with the needs of tech firms and social media companies like Twitter, Facebook, and others to assure their customers that they will do everything possible to protect them online. All parties involved have to understand that excessively lowering the level of protection provided to individual citizens entails a risk that others with advanced skill sets would be able to breach the communication systems used by ordinary citizens or even government agencies. The fact is that in the last three years there have been major breaches of data in the public and private sectors, and despite the best firewalls and other security measures, we still remain frighteningly vulnerable to hacking. The tech companies have made a case for self-policing and limited government interference in their operations. Leading companies like Twitter and Facebook justify avoiding limited government regulation and interference by engaging in aggressive takedowns of ISIS propaganda.

United States Law Enforcement Activities

Federal Level activities by the FBI and DOJ include a range of outreach efforts to social media organizations for input and cooperation. In February 2015, the US Justice Department met executives from Apple, Twitter, Snapchat, Facebook, and MTV.3

Then, in January 2016, US anti-terrorism officials again met with Silicon Valley executives in a closed-door summit to discuss online counter-ISIS measures, with both sides realizing that government efforts alone might not be enough. The government was wary of encroaching on First Amendment rights.4

The predominant method used for years by the FBI and other law enforcement agencies for monitoring ISIS jihadist activity has been a combination of acting on tips from concerned citizens and using undercover officers, informants, and authorized surveillance. Many of the 90+ cases before the federal courts involved a combination of informants and undercover confidence building with the suspects. In many cases there were overlapping suspects, all of whom were intending to go to Syria or in some cases carry out US attacks from within.

US Department of State—“Think Again, Turn Away”

The US State Department has been building coalitions to fight ISIS under Secretary of State John Kerry. The department that spends its time dealing with international diplomacy has been tasked to confront terrorism and online recruiting in several ways. The unit inside the State Department asked with confronting the issue was the Center for Strategic Counterterrorism Communications, or the CSCC. The CSCC was established in September 2010.5

The State Department has said it was well aware of the intrinsic relationship jihadist expansion has with the use of the Internet and social media. Deputy Secretary of State and former Deputy National Security advisor Tony Blinken said the department could see a decrease in the space in which ISIS can operate online and that efforts via suspensions were taking their toll.6

The “Think Again, Turn Away” project was launched in 2014 before the declaration of the creation of the Islamic State. The purpose of the project was to confront extremism with alternative messages. Using the twitter handle @ThinkAgain_DOS, the channel intended to spread counter-extremist ideas. But without knowing who the target recipients were or what channel would be used by them, the government use of a Twitter channel would not result in getting counter- or alternative messages to those likely to be attracted to watching jihadist materials in the first place.

After the world saw what ISIS was capable of doing, the CSCC prepared a four-minute video called Welcome to the Islamic State that sought to use the savage imagery of ISIS to counter recruiting with images of tortured Muslims, mosques being blown up, and other terrorist outrages. The video was released September 5, 2014.7 There was no evidence the video led to any success in stopping the recruiting of foreign fighters.

The efforts of the State Department include using voices of Muslim scholars to refute the religious claims of ISIS. In doing so, ISIS then retaliates on those scholars, smearing them as apostates for working with Western governments, especially the United States.

US Military vs. ISIS Cyber

As noted in the Operation Vaporize section of Chapter 1, the US military and coalition forces have been busting media centers related to ISIS since it was called AQI. With big hauls of CDs, computers, jump drives, and terabytes of data, the kinetic effort to destroy ISIS media cannot be underestimated. When coalition forces put pressure on all the towns around Mosul in 2016, there were reports of ISIS media and IT techs leaving the group.8 An anti-ISIS activist named Raafat al-Zarari told ARA News that many who fled were American citizens who have left the Iraq-Syria area for Turkey.

In January 2016, French Air Force fighter jets bombed a building purported to be a key ISIS media center in Mosul. In response to the strike, Amaq stated that ten of the Mosul media crew were killed.9 On August 31, 2016, the US military killed the ISIS spokesman, Abu Muhammad Al-Adnani. The operations continued days later with the death of the Minister of Information, Wa’el Al-Rawi.

The Launch of a New Offensive by Cyber Command

In March 2016, Defense Secretary Ash Carter and Joint Chiefs Chairman Gen. Joseph Dunford announced the intent to use active, offensive cyber operations to “disrupt ISIL’s command and control, to cause them to lose confidence in their networks, to overload their network so it can’t function.”10 The “Cyber Command” has been focused on state actors like the Chinese, the North Koreans, and the Russians. Based in Fort Meade, Cyber Command has been active since 2009. During the 2016 announcement about launching the new offensive, Carter told CNN, “We are dropping cyber bombs.”

Defense Secretary Carter told Congress that these were the new orders to Cyber Command:

• interrupt their command and control of forces

• interrupt ability to plot

• interrupt finances

• interrupt ability to control population

• interrupt ability to recruit

ANTI-ISIS EFFORTS ABROAD

While the laws in the United States continue to adapt to the changes driven by ISIS activities, countries in the rest of the world have their own ways of dealing with terrorism and abuse of social media. These range from imposing heavy sentences for viewing materials associated with ISIS to shutting down or blocking entire communication platforms in an attempt to prevent abuse of services like Twitter, WhatsApp, and Facebook to coordinate terrorist attacks or, as critics of those plans also note, to crack down on legitimate dissent around the world.

The efforts against ISIS in the Muslim world vary, but in the first two years after the invasion of Iraq in 2003 there was little in the way of a coalition despite the damage done to countries in proximity to and immediately threatened by ISIS. Jordan and Egypt have stepped up strikes against ISIS after attacks on their citizens. In both cases, strikes occurred just after videos were released showing execution of their citizens.

In IT responses, many countries already practice strict controls over their communications and Internet usage. In particular, though, some countries have acted upon the concerns of cover planning hidden by encryption. Bangladesh resorted to blocking many social media platforms to cut off communications to potential terrorists. UAE imposed a fine of $545,000 for those caught using a VPN to bypass their strict one-IP system.11

European Effort against ISIS Cyber

Even as the UK exits the EU, the efforts to deal with technology and militants continues. The UK has a Twitter channel like the US State Department that was aimed at dissuading terrorist recruiting. As of September 2016, the Twitter channel had 18.1k followers and 4,689 posts starting from July 2015, advising users to follow the channel for the latest information and to use the hashtag #DefeatingDaesh. The US State Department has morphed again, and the @ThinkAgain_DOS channel has 67 followers and two tweets. Its replacement channel, @TheGEC or Global Engagement Center, had 26.8K followers as of September 1, 2016. Not very impressive!

The UK has also cracked down on several radicals including Anjem Choudhury and Abu Haleema. Choudhury was convicted in late July 2016 and sentenced to five years after years of incendiary speeches and explicit taunting of UK authorities by openly and widely expressing extremist views. Finally, after he proclaimed his loyalty to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and ISIS, and then encouraged others, the British authorities stepped in and charged him under Section 12 of the Terrorism Act of 2000.12

Like Choudhury, one of the livelier characters on YouTube and via Telegram was extremist Abu Haleema, who regularly rants in videos and posts via Telegram and Twitter. He speaks in repeated phrases intended to cause the thoughts to sink in to the listener. In early January 2015, Twitter shut down his channel as part of an effort, reportedly directed by a combination of MI5 and CIA efforts.13

Investigatory Powers Bill

Regarding legislation, Parliament has been debating a bill that calls for the banning of encrypted messaging for potential terrorists including usage of Facebook, WhatsApp, and iMessage.14 In addition, the bill calls for increasing data collection of traffic between suspects of targeted investigations. The bill was met with resistance from privacy advocates, but it passed in the House of Commons.15

France

In the aftermath of the attacks in Paris in November 2015, France sought to work with the tech giants to deal with terrorist use of advanced encryption tools and the Internet for recruiting. Officials met with Facebook, Twitter, Microsoft, Google, and Apple.16

In an effort similar to that of the US State Department, the French authorities launched a hashtag campaign under “StopJihadisme” meant to teach parents to look for indications that their children might be getting radicalized. Yet critics suggested the campaign was a waste that failed to reach the audience of people who would most likely turn to ISIS. The campaign included a video that was similar to the one released in the United States, a recut of ISIS videos meant to destroy the notion of a utopian destination for the pious Muslim.17

The European Police Office, or Europol, began efforts to find those behind publication of ISIS media in July 2015.18 The agency said the effort would include sending take-down notices with the demand that accounts be removed within two hours of notice. The effort would also include a more concerted attempt to detect noteworthy channels in order to flush out leaders and media centers.

Silicon Valley vs. ISIS

It wasn’t something Silicon Valley had experienced before. Since 2003, foreign terrorists were now controlling their operating systems and custom coding them to spread their messages and recruit fighters to attack abroad. The flood of ISIS on the social media stage was initially overwhelming for YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook. The tech giants were dragged into the fight against their will, but they’ve had no choice but to respond. With the demand to clean up their sites coming from their users and lawmakers worldwide, each of the firms have increased their efforts to stop and prevent exploitation of their systems for terrorist media propagation and recruiting. Beyond these three, communications like Telegram, Wordpress, and Archive.org have stepped up efforts to remove ISIS from their systems. In the case of Telegram, there are intelligence agencies and private analytical firms who express resistance to removing these channels out of a need to keep an eye on the organization instead of driving them further into the dark.

Twitter vs. the ISIS Fanboys

If there was one social media outlet that was perhaps impacted the most during the rise of ISIS on the world stage in the summer of 2014, it was Twitter. While many people do not know about the world of online forums, secret or not, they do know about Facebook and Twitter and have become accustomed to getting news and lifestyle announcements via Twitter. ISIS, AQ, and other jihadist groups are using the same tools for their message but with a quite different set of goals.

Twitter has also announced its own war on ISIS in a company blog post, where it was revealed that since mid-2015 it has suspended 125,000 pro-ISIS or terrorist accounts. Twitter’s blog reported they had increased the staff dedicated to the task of keeping up with reports on suspicious profiles and posts submitted by users:

“We have increased the size of the teams that review reports, reducing our response time significantly. We also look into other accounts similar to those reported and leverage proprietary spam-fighting tools to surface other potentially violating accounts for review by our agents. We have already seen results, including an increase in account suspensions and this type of activity shifting off of Twitter.”19

“We condemn the use of Twitter to promote terrorism and the Twitter Rules make it clear that this type of behavior, or any violent threat, was not permitted on our service,” the blog post read. “As the nature of the terrorist threat has changed, so has our ongoing work in this area.”20

After the Bastille Day attack, Twitter demonstrated it understood how ISIS would exploit the tragedy on their platform and rapidly suspended accounts that appeared to be pro-ISIS applauding the truck attack during the holiday in the southern town of Nice. When users posted under “#BlessedNiceAttack” or the “#BattleOfNice” tags and more, they were suspended in far less time than past suspensions had taken.

The company defended its performance in keeping up with the proliferation of ISIS profiles by noting that experts in the field suggested it was impossible to develop the magical algorhythms that would perfectly detect who was participating in terrorism. They disclosed that they do use methods similar to their spam tracking that identify activities associated with accounts that have been identified with ISIS activities.

Facebook vs. ISIS

Much like Twitter, Facebook has been very active in removing suspect profiles, pages, and groups from its website. Facebook, in the past, has cracked down on ISIS-related accounts, including banning a company profile that was supposedly owned by the San Bernardino Shooter Tashfeen Malik. However, the social media website relies heavily on users bringing profiles to a moderator’s attention by either “liking” the page or “flagging” it for violating its community standards.21

Google and YouTube vs. ISIS

Interwoven giants Google and YouTube are still used by pro-ISIS supporters but with far less frequency than just after the announcement of the caliphate in the summer of 2014. The use of the video tools, personal profile pages, email, and Google drives have made this tech giant very appealing to the jihadists.

One of the key tech giants infected with the ISIS bug was Google. Through its email systems, personal websites, google drive sharing, and of course the very powerful YouTube, Google became the center of attention in the beginning of the battle with ISIS in the summer of 2014. With postings of beheadings grabbing the news, Google’s subsidiary video site YouTube was caught in the cross fire between the terrorists of ISIS and the demands of free speech in its home country of the United States.

The use of YouTube by ISIS was an easy choice considering the open source nature of the platform, but it wasn’t the only video sharing site being used by the terrorist organization. The propagation teams use dozens of lesser-known sites including sites that are beyond the reach of U.S. legislative control. Yet Google wasn’t simply picked for YouTube; the terrorists exploited Google both for its email and its Google drives for hosting video, audio, and document files.

Tech juggernaut Google announced that it would take the fight to ISIS by introducing an alteration of its search results. Jigsaw, an advanced research outfit, will redirect anyone searching pro-ISIS terms and phrases to antiextremist messages and videos. The campaign behind this was called the “Redirect Method.”22

Google hopes to inspire anti-ISIS campaigns by using Jigsaw instead of automatically integrating it into its search results. The campaign seemed to be effective during an eight-week trial from January to March of 2016, reaching at least 320,000 people who searched for one of more than 1,000 Islamic State-related keywords.

The method placed ISIS-related search results close to ads that had links to counterradicalization links. Jigsaw and other groups affiliated with the method did not create new anti-ISIS content, but simply redirected searchers to preexisting content on YouTube. The effort led by Jigsaw, now a division of Alphabet, Google’s parent company, follows other initiatives to counter extremist messages on the web. The Jigsaw project comprised 30 ad campaigns and 95 unique ads both in English and Arabic.

Archive.org

There are few places more interesting on the web than Archive.org, and ISIS knows it. They reliably use Archive.org as their primary depot for the highest-quality versions of their video releases, and the source location for their audio and pdf releases like Dabiq. But unlike their early efforts at exploiting it, ISIS began having difficulty successfully keeping materials posted there for long, as Archive.org caught on and undertook changes to be more responsive in taking down the propaganda materials.

The Internet archive, an enormous digital library, was hacked because it hosts ISIS materials. The Twitter account @AttackNodes took credit for the hacks with the hashtag #opISIS, which was affiliated with Anonymous. However, Anonymous members have not gotten in contact with Attack Nodes.23

CORPORATE FIGHT VERSUS LEGISLATIVE OR EXECUTIVE OVERREACH

There has been a balancing act between private corporations and the power of the US government given its desire to stop terrorism and the desire of the tech firms to be able to retain customers who value their privacy. The tech industry has long pushed back at congress regarding outside policing of their systems and instead tends to offer plans and evidence of action to assure the legislative body that the industry is quite capable of taking care of itself and that customers have expressed concerns over privacy to the companies. As noted earlier, the most substantial battle came when the FBI asked Apple to help breach the phone at the center of the San Bernardino attack in December 2015. Apple refused on the grounds that breaking the encryption with a backdoor for law enforcement was not an option it would pursue. Apple claimed that it could not break the encryption without wiping the iPhone, but the FBI finally managed to succeed.

BRAINPOWER VERSUS ISIS—THE THINK TANKS

There are several organizations and private analysis firms and think tanks that are involved in the daily effort to defeat ISIS online. The research programs are blooming as the need for more awareness of what motivates people to join extremist groups like ISIS is on the rise.

While there are organizations that simply observe and report what they see, others are engaged in direct efforts in counterradicalization, counterrecruitment, counterintelligence, and more.

Muflehun

Humera Khan, an executive director for Washington, D.C.-based Muflehun (Arabic for “those who will be successful”), said that it’s not enough to just shut down ISIS websites. A more coordinated effort was required. “The ones who are doing these engagements number only in the tens. That is not sufficient. Just looking at ISIS-supporting social-media accounts—those numbers are several orders of magnitude larger,” says Khan. “In terms of recruiting, ISIS is one of the loudest voices. Their message is sexy, and there is very little effective response out there. Most of the government response isn’t interactive. It’s a one-way broadcast, not a dialogue.”24

Quilliam Foundation

A British counter-extremism think tank founded by Ed Husain, Maajid Nawaz, and Rashad Zaman Ali, has used its own antiradicalization videos to combat terrorist ideology.25 The foundation was established in 2007.

Brookings Institution

A Washington, D.C.-based public policy organization. A study led by J.M. Berger of the Brookings Project found that pro-ISIS Twitter accounts had an average of about one thousand followers. Pro-ISIS accounts were also found to be more active than anti-ISIS ones. ISIS’s successful spread of its ideology can be attributed to a “small group of hyperactive users numbering between five hundred and two thousand accounts, which tweet in concentrated bursts of high volume.”26 The report also found that while a minimum of one thousand pro-ISIS accounts were suspended from Twitter between September and December 2014, there was also possible evidence of thousands more.

The Soufan Group

The highly respected counterterrorism advisory firm, The Soufan Group, has done extensive research into the use of media for recruiting foreign fighters that prove invaluable to researchers worldwide. They also publish a daily newsletter with up-to-the-minute analysis on terrorism around the world.

STUDENT POWER

Outside of tech companies, college students have been recruited in the fight against ISIS. The US departments of State and Homeland Security, Facebook, and Ed Venture Partners have created a competition to challenge college students to promote anti-ISIS ideology via social/digital media.

In 2015, students from Missouri State University won the competition with their campaign called One95. The campaign had a website, testimonial videos, and a tweet-a-thon. The group’s efforts turned into 200,000 Facebook and Twitter impressions. Eventually, the One95 Global Youth Summit against Violent Extremism was held in the fall of 2015 at the UN in New York.27

THE GRASSROOTS FIGHT

In what may be a precedent in the history of cyber war, citizens were continuing to get involved in the fight. With a range of forces from moms who decided they had to confront the terrorists who radicalized their sons to lone cyber warriors like “Jester the mystery hacker,” who posted credits for taking down forums and inflicting other mayhem against the Islamic State to the news headline-grabbing fight between Anonymous and the terrorist group.

Figure 90: Anonymous Logo. (Source: TAPSTRI)

Anonymous vs. ISIS

Evolved from users of 4chan, an imageboard website launched in 2003, Anonymous has become the most recognizable name in hacking and activism or the more common portmanteau term “hacktivism.” Anonymous gained attention through its history of focusing campaigns against Scientology in its “Project Chanology” in 2008; Operation Payback in 2010, which consisted of a series of DDoS attacks against companies and law firms fighting online piracy; and their operations focused on groups seen to be racist or bigoted by Anonymous including the KKK (2015), Storm Front (2015), and Westboro Baptist Church. It has intervened in cases like the Steubenville rape case of 2013, or the Ferguson, Missouri, shooting case of Mike Brown, or even launched a DDoS attack over police officer Jeffrey Salmon’s shooting of a dog, which was captured on video in June 2013.

Anonymous also has little fear about threatening violent organizations. In October 2011, the group threatened the Mexican drug cartel, Los Zetas, with releasing personal information that could harm the Zetas if they didn’t release an Anonymous member. The group attacked the CIA’s website in 2012 and the Interpol website in 2012.28

#OpISIS Begins

How Anonymous went to war with ISIS:

ISIS; We will hunt you, Take down your sites,

Accounts, Emails, and expose you…

From now on, no safe place for you online…

You will be treated like a virus, And we are the cure…

—Anonymous

In response to the shootings at the Charlie Hebdo offices on January 7, 2015, in Paris, Anonymous declared war on al-Qaeda and what would become ISIS in its campaign to destroy jihadist websites and social media accounts. #OpCharlieHebdo was crafted to attack jihadist online resources in retaliation for the murder of twelve people.29 The first site Anonymous claimed to have knocked down, ansar-alhaqq.net, was only down for a few hours before it reappeared. On February 9, 2015, Anonymous claimed to have removed 800 terrorist Twitter accounts and a dozen Facebook accounts.30

Paris Attacked Again

In November of 2015, days after the terrorist attacks in Paris that killed 129 people, Anonymous issued a video promising retaliation against the group. “The War has been declared,” the voice started in French. “Prepare yourselves. These attacks cannot remain unpunished. This is why the Anonymous from all over the world will hunt you down. Expect many cyber attacks.” The video then closed with expressions of condolence for the victims and families of the attacks that rocked the French capital.

Shortly after it initially began its “war” with ISIS in November, Anonymous claimed to help get 5,500 ISIS Twitter accounts taken down, which supposedly jumped to 20,000 by mid-February through its operation “#OpParis.”31 The hacktivist group claims to have foiled an attack in Italy because of its efforts, all a part of its “Operation Isis” campaign.32

ISIS Responds to Anonymous

Though ISIS fanboys often pay attention to their opposition, they don’t always take the time to respond. However, in a post on November 17, 2015, on a pro-ISIS Telegram channel came a taunt aimed at the virtual nature of the group. “What are they gonna hack?”

The Brussels Attack

ISIS attacked the Brussels Airport in Zaventem and the Maalbeek metro station, killing 32 people and injuring more than 300. Following the attacks on March 22, 2016, Anonymous released a video threatening ISIS again.

“We have laid siege to your propaganda websites, tested them with our cyber attacks, however we will not rest as long as terrorists continue their actions around the world,” a masked spokesman said in the video.”We will strike back against them. We will keep hacking their websites, shutting down their Twitter accounts and stealing their Bitcoins. We defend the rights of freedom and tolerance.”33

The Orlando Response

Omar Mateen struck Pulse, a gay night club in Orlando, Florida, on June 12, 2016, killing 49 and injuring 53 others. The event stunned the nation. Following the Orlando shooting, Anonymous hacked pro-ISIS Twitter accounts and flooded them with Gay Pride messages, photos, and banners.34 The hacker operating under the name “WauchulaGhost” breached several accounts and repurposed the look of their graphics to a rainbow décor and phrases like, “I’m Gay and I’m Proud!”35

Effectiveness

Anonymous has its detractors in the counterterrorism game. There are many analysts who have criticized the group for its lack of discernment regarding accounts attributed to ISIS. This results in accounts being falsely flagged for being Islamic in nature and tone but not associated with ISIS. Twitter issued a confirmation that it took down accounts accused of being ISIS that turned out not be ISIS-related.36

Ghost Security Group (GSG)

One group that sprung from the Anonymous versus ISIS battle was formed by a hacker named Mikro and directed by another named DigitaShadow. After breaking away from Anonymous in May 2015,37 Mikro launched two groups to combat ISIS, the Ghost Security Group (GSG) and CtrlSec. Ghost Security Group started with an intentionally different angle from Anonymous that included cooperating with law enforcement and private security firms and being willing to get paid for the work.

GSG describes itself as a “counterterrorism organization” focused on terrorism only, whereas Anonymous was known for shifting focus when an outrage calls. One minute Anonymous may be focused on Charlie Hebdo, and the next it was aimed at Ferguson, Missouri. GSG claims its focus was consistently aimed at ISIS and related groups.

The group doesn’t reveal its methods or logistical arrangements as an organization. Gizmodo stated that GSG claimed 16 members in the United States, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia.38 They also noted that DigitaShadow had come into the crosshairs of law enforcement because of participating in DDoS (Distributed Denial of Service) attacks related to Ferguson, Missouri, protests.39

In July 2015, GSG made the claim that it had intercepted information while doing network analysis on Dark Web sites that uncovered a plot to attack a Tunisian market. This would have been a follow-up attack to the June 2016 beach attack in Tunisia. The group cooperated with a private security firm known as Kronos Advisory to then send the information to the FBI. The outcome was not revealed.

There was another group affiliated with Anonymous called “Ghost Security” that has become a rival group due to the criticism of GSG’s cooperation with government law enforcement agencies and private security firms like Kronos Advisory. In late November 2015, the GhostSec hacktivists attacked the Isdarat site on the Dark Web used to host videos and gave it a Prozac rebranding.40

The Atlantic Profiles GSG Founder Mikro on ISIS

One hacktivist, named Mikro, who was a member of Ghost Security Group, was profiled in an article by the Atlantic magazine. Mikro was supposedly an “operations officer” for GhostSec, a group whose mission was to target “Islamic extremist content” from “websites, blogs, videos, and social media accounts,” using both “official channels” and “digital weapons.”41 So far, the group claims to have overwhelmed servers in more than 130 ISIS-linked websites in coordinated attacks.42

Mikro later formed a second group, this time not affiliated with Anonymous. The new group was dubbed CtrlSec. While similar to GhostSec, CtrlSec accepts financial support and has a defined structure and hierarchy, unlike Anonymous. Its goal was to shut down pro-ISIS Twitter accounts. On a near-hourly level, the four Twitter accounts associated with CtrlSec (@CtrlSec, @CtrlSec0, @CtrlSec1, @CtrlSec2) publish links of Twitter accounts targeted for take-downs. Mikro claims to have shut down tens of thousands of accounts with the group.43

Figure 91: Jester Logo. (Source: Jester)

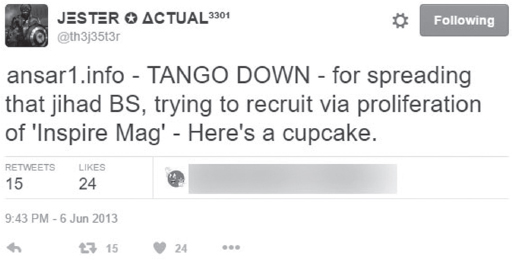

The Jester (th3j35t3r)—The Cyber Vigilante

Before there was #OpISIS, there was ‘th3j35t3r’ and his efforts to destroy jihadist web sites and materials found on the Internet. Described sometimes as a “patriot hacker,” Jester has used his skills to confront not only ISIS, but Anonymous, as well. He claims to be a “former military man” and often speaks in military jargon. His fight with targets like Anonymous, Wikileaks, Westboro Baptist Church, and jihadists all intersect at an interest in looking out for the welfare of members of the military. Hitting the Twitter scene in late 2009, Jester has been documenting his fight against online extremists for years and across several platforms including iAWACS (online surveillance), Xerxes (DDoS program), and other home-brewed web tools.44

Jester reportedly got into hacktivism in reaction to Wikileaks releases. He claims he was concerned that files exposed by the organization would endanger our troops. Because Anonymous was very much aligned with Wikileaks, the fight expanded to them, too. He’s shown strong animus against Anonymous, their rival group Lulzsec, and Wikileaks.

He then moved on to Islamic terrorists.45 His first claim to fame was taking out a Taliban site, alemarah.info. On January 1, 2010, he Tweeted, “www.alemarah.info is now under sporadic cyber attack. This ‘Voice of Jihad’ served only to act as a tool for terrorist. OWNED. By me, Jester,” after he hit the site with a DDoS attack by his customer customized DDoS tool codenamed XerXes.

Figure 92: Jester Tweet 1-alemarah.info. (Source: Twitter)

He proceeded for years to take down site after site, each time punctuated with his trademark tag Tango Down. A check of his Twitter time over the years shows a long list of take-downs starting with the January 2010 toppling of the Taliban site. He says he stopped keeping up with how many sites he’s taken down after he topped 179.46

Figure 93: Jester Tweet 2-cupcake specials. (Source: Twitter)

“Approximately five years ago I realized that there was a growing threat from jihadis online using the Internet to recruit, radicalize, and even train homegrowners,” The Jester told NBC Chicago. “I decided to research their favorite haunts, collect intelligence on the users and admins and in many cases remove them by force. I tended to hit some sites a lot and leave others. This had the effect of herding/funneling them into a smaller space. And smaller spaces are easier to watch and monitor.”47

One of his next operations was to use a Libyan newspaper to spread disinformation. His psychological operations campaign began just before the toppling of Muammar Gaddafi in 2011. He appeared to have fabricated articles in the online feed of the Tripoli Post in March 2011 in order to affect troop movements in the region. His method was determined to be the use of a code injection in the link he provided via a bit.ly url, which included an additional link to offsite content that was aimed to suggest that Gaddafi’s army was abandoning him.

He has successfully eluded being outed despite a range of opponents, including Anonymous and many nation states, who clearly would love to do so. His websites and social media accounts have been suspended several times over suspected hacks including having his domain name, jesterscourt.cc, seized by the US federal government.48

“[T]he bad guys want to slice my head off on YouTube with a rusty blade, and the good guys want to lock me up in an orange jumpsuit … along with the bad guys.”49

Jester’s criticisms of Anonymous have been well publicized in the hacker-oriented news blogs. He has stated the amorphous group lacks a check on their efforts to confront ISIS, that they aren’t serious, and that they are largely ineffective.

“All they’ll do is dump a random list of names from a previous hack and claim it’s ISIS members, and they’ll report ‘ISIS’ accounts to Twitter. Pretty standard BS from them,” he told Paul Szoldra from Tech Insider in Nov 2015.50

Compared to the Anonymous hackers who focus on ISIS, The Jester sees himself as more of a patriot, looking to protect US citizens from those he deems a threat.51 In an article on his official website, in July 2015, he criticized the US government’s efforts:

I didn’t go out of my way to broadcast my approach except in a select few places. It was quite simple. I made it my mission to “constantly disrupt and/or disable their self-managed offshore servers, to sow distrust among the users and total frustration among the site administrators … strive to make it too much of a pain in their puckered asses to bother using their own resources … thereby forcing them off those boxes and ‘herding’ or ‘funneling’ them into a smaller space. Because smaller spaces are easier to watch and monitor.” The whole effort was well-documented and relatively successful, in at least 179 cases (via CNN) and independently confirmed here (by NBC).52

In the end, Jester’s view is simple: “You can ask an ISP nicely to perform a takedown, but mostly they don’t, that’s where I seem to fit in.”53

Interesting bit: When Jester decided to attack the controversial Westboro Baptist Church’s website over their protests at soldiers’ funerals, he did so with a 3G phone.

AVOIDING SPY ON SPY

The rush to take down ISIS materials has raised an issue on accountability related to who should decide what is taken down and how will that be decided and how do take downs affect others. On the real battlefields, coordination between allied forces is paramount to mission success and vital to the safety of friendly forces. In the cyber world, the same rules apply and may even have life-and-death consequences. The stakes are high when undercover operations lurk behind the channels of Twitter and Facebook or on websites, forums, or hidden channels. The court records alone indicate extensive contact between federal agents or informants and terrorists or soon-to-be terrorists. Therefore, the takedowns of jihadist materials run the risk of blinding or harming those operations.

In 2008, a website used by the CIA and the Saudi Government to conduct intelligence on extremists in Iraq and the Middle-East region was taken down.54 The site became the focal point of an intense debate in Washington, as policy makers tried to defend the validity of the concerns. On one hand, the CIA was looking to lure terrorists to the website so they could corral and gather intelligence on their activities. On the other, the US military and others argued that the content posted would lead to further threats against US troops, especially in Iraq. In the end, the US military won out, and the site was targeted, just as US Central Command wanted. The group tasked with the assignment was called the Countering Adversary Use of the Internet program under the Fort Meade-based Joint Functional Component Command-Network Warfare.

Another example concerns the use of the web to archive jihadist materials. Researchers gather ISIS material so it can be reported to appropriate authorities and analyzed for intelligence value, but non-Arab speakers may not realize the purpose of the site and flag it for removal. A blogger at InfoSecIsland.com published a review of Jester’s take-down effort and noted that he had taken down a research site hosted by the blogger. The blogger stated that a little bit of examination might have led a reasonable person to realize that the site owner was a critic of ISIS, not a supporter.55

The FBI is known to have used the Internet to lure suspects to click on terrorism cases like Michigan resident Khalil Abu Rayyan.56 Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that if the average citizen issues a take-down on a Twitter, Facebook, or other type of profile without knowing what activity is occurring behind that channel, then they may disrupt an ongoing investigation into a terrorism case.

One solution to this problem would be to continue to ensure public participation while having the tech companies who are stuck in the middle turn over the complaints to law enforcement and leave the judgment of terrorist determination to law enforcement. This could provide accountability for operations and places the greater burden of consequences on law enforcement to handle criminal behavior instead of the companies in the middle. A fast track system to the federal government from the social media, hosting, ISP, and other responsible parties who fall between the users of the Internet and terrorists would help facilitate the notification. Those records could be checked against undercover operations and work to prevent disruption of investigations.