INTRODUCTION TO

THE THIRD EDITION

Alchemy is philosophy; it is the philosophy,

the seeking out of the Sophia in the mind.1

—mary anne atwood

T he Philosopher’s Stone was written in 1936–37 when Israel Regardie was confined to bed for a prolonged period of time due to a severe bout of bronchitis. To make the best use of this downtime, Regardie was determined to tackle a lengthy and difficult book on alchemy, Mary Anne Atwood’s A Suggestive Inquiry into the Hermetic Mystery, the meaning and implications of which had escaped him in earlier reads. Published in 1850, Atwood’s comprehensive tome documented the enormous impact of hermetic philosophy on human spirituality. A Suggestive Inquiry presents readers with cryptic alchemical treatises such as “The Golden Tractate of Hermes” and “The Six Keys of Eudoxus”—documents infused with riddles and symbolic codes used to secretly communicate to fellow alchemists the true purpose of the Hermetic Art. In studying this complex text, Regardie found that “Suddenly, and to my utter amazement, the whole enigma became crystal clear and alive.” After this breakthrough, insights came rapidly, and over the course of the next two weeks, Regardie wrote the bulk of The Philosopher’s Stone which was published in 1938.

Regardie’s admiration for Atwood’s work is not surprising. Born in 1817, the only child of metaphysical historian Thomas South, Mary Anne Atwood took an active role in her father’s research at an early age. Her first book, Early Magnetism in Its Higher Relations to Humanity, was published under a pseudonym in 1846. Her magnum opus, A Suggestive Inquiry into the Hermetic Mystery, was published by her father in 1850. Later, both father and daughter became convinced that the book exposed far too many alchemical secrets, and except for a few copies sold or owned by the author, all other copies were destroyed. After the death of her father, Mary Anne married a clergyman, Rev. Thomas Atwood, but she continued to study hermetic and theosophical writings for the rest of her life.

What was the secret that had been revealed in A Suggestive Inquiry? It was that alchemy was actually a method for transforming the human soul through altered states of consciousness, during which the soul ascended to the spiritual world for powerful transformational experiences and descended back again into the physical body. Atwood posited that all mention of metals, minerals, and alchemical processes were merely symbols and metaphors for spiritual alchemy. This was the ‘secret’ that Atwood attempted to re-conceal once the genie had been let out of the bottle, and it was also the secret that would captivate Regardie’s mind as he recuperated.

At this point in his life, only a couple of years after finishing his Golden Dawn studies and having left the Bristol Temple of the Stella Matutina, Regardie was convinced that alchemy was in reality a thinly veiled psycho-spiritual process—the operations in laboratory alchemy that professed to work on metals, minerals, and plant matter were essentially focused solely at man’s mind, soul, and spirit. He had concluded that “practical” laboratory alchemy was simply wrong-headed, and that only theoretical, spiritual, or psychological alchemy was valid. Although he admitted that a certain number of alchemical texts could be construed as having a literal, “primitively chemical” interpretation, Regardie felt that alchemical writings should be “interpreted solely in terms of psychological and mystical terms.”

Some thirty years after writing The Philosopher’s Stone, Regardie underwent a change of heart on the matter after attending a seminar conducted by Albert Riedel, otherwise known as acclaimed alchemist Frater Albertus, founder of the Paracelsus Research Society in Salt Lake City. In his Introduction to the Second Edition of this book, Regardie candidly acknowledged his earlier mistake and changed his opinion about the validity of laboratory alchemy, relishing the opportunity to “eat crow” and admitting that “in insisting solely on a mystical interpretation of alchemy, I had done a grave disservice to the ancient sages and philosophers.”

In spite of this, Regardie still felt that his initial analysis of the three alchemical treatises cited in The Philosopher’s Stone were valid and useful. His original approach was to analyze these seventeenth-century texts emblematically, using the symbol systems of magic, Qabalah, and Jungian psychology to explain how laboratory operations described by alchemy are in reality psychoanalytical processes of self-realization and spiritual attainment:

Like modern psychological methods the alchemical formulae have as their goal the creation of a whole man, of integrity. … Not only does Alchemy envisage an individual whose several constituents of consciousness are united, but with the characteristic thoroughness of all occult or magical methods it proceeds a stage further. It aspires towards the development of an integrated and free man who is illumined. It is here that Alchemy parts company with orthodox Psychology.2

Because he felt that his work on The Philosopher’s Stone was the product of genuine illumination and insight, Regardie was tempted to rewrite parts of the book in order to incorporate what he later learned about laboratory alchemy through his work with Frater Albertus. He refrained from doing so because he felt that the book in its original form could still be of immense value to students who were at the same stage in their spiritual evolution as he had been in 1937. However, he also suggested that the book “be supplemented by other reading of more recent vintage.” As Regardie later stated in an essay on “Alchemy in the World Today”:

Alchemy is once more rearing his head not only in this vast country of ours, but in Great Britain and in the heart of Europe as well, and in the Antipodes. There is communication now-a-days between its advocates as there always has been, since many of the famous texts were simply the means whereby one adept in the art could convey to others something of his own knowledge and experience.3

Which brings us to one of the reasons for publishing this new edition of Regardie’s classic text. With the exception of added footnotes and a few minor changes in spelling, Regardie’s initial thoughts on alchemy as exemplified in The Philosopher’s Stone stand as they were first written. Rather than rewrite the original text to accommodate information on laboratory alchemy as Regardie was tempted to do in 1968, we opted to supplement the text with articles on practical alchemy contributed by contemporary alchemists and writers in the later part of the book. The result is a balanced approach that honors the past but also addresses current views on the Hermetic Art, offering readers something of the knowledge and experience of modern practitioners, particularly those working in the Golden Dawn Tradition.

Israel Regardie’s influence on modern magicians cannot be overstated. With the publication of The Golden Dawn: The Original Account of the Teachings, Rites, and Ceremonies of the Order of the Golden Dawn (1937–40), Regardie made the Golden Dawn system of magic available to a wide and eager audience of esoteric students. According to Francis King and Isabel Sutherland: “That the rebirth of occult magic has taken place in the way it has can be very largely attributed to the writings of one man, Dr. Francis Israel Regardie.” However, students have not always found the four volumes of The Golden Dawn an easy read. In many of his other books, Regardie endeavored to shed light on the various magical topics covered by the Golden Dawn’s teachings. These works included: A Garden of Pomegranates (1932), The Tree of Life (1932), My Rosicrucian Adventure (1936) The Middle Pillar (1938), The Art and Meaning of Magic (1964), Twelve Steps to Spiritual Enlightenment (1969), A Practical Guide to Geomantic Divination (1972), How to Make and Use Talismans (1972), Foundations of Practical Magic (1979), Ceremonial Magic (1980), The Lazy Man’s Guide to Relaxation (1983), and The Complete Golden Dawn System of Magic (1984).

However Regardie’s most important book was undoubtedly The Golden Dawn, since it contained much of the Order’s essential teachings in the form of initiation ceremonies, assigned gradework for the various levels of student development, magical diagrams and symbols, side lectures, rituals, meditations, and exercises, as well as ritual outlines for advanced Adept-workings.

Some of the more advanced magical workings of the Golden Dawn were described in a Second Order paper entitled “Z.2: The Formulae of the Magic of Light.”4 This paper was given out to those Initiates who had attained the grade of Zelator Adeptus Minor and higher. In his introduction to this manuscript, MacGregor Mathers described how the initiation ceremony of the Neophyte grade (the 0=0 Ceremony) was filled with several formulas for higher ritual work by Adepts of the Order:

In the Ritual of the Enterer are shadowed forth symbolically, the beginning of certain of the formulae of the Magic of Light. For this Ritual betokeneth a certain Person, Substance or Thing, which is taken from the Dark World of Matter, to be brought under the operation of the Divine Formulae of the Magic of Light.5

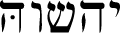

In other words, the Golden Dawn’s Neophyte Ritual contains all the formulas necessary for practical magic, hidden under many layers of symbolism. All magic performed by the Adepts of the Order was classified as one of five types listed under the five letters of the Pentagrammaton or “five-lettered name.” This refers to the Hebrew name of Yeheshuah (

) or the Hebrew name of Jesus, which is the Tetragrammaton, YHVH (

) or the Hebrew name of Jesus, which is the Tetragrammaton, YHVH (

), with the letter Shin (

), with the letter Shin (

), representing Spirit, placed in the center of the name. Each letter of the Pentagrammaton signified a different type of magic known collectively as the Magic of Light. The five types of the Magic of Light are classified as follows: Evocations and invocations fall under the category of the Hebrew letter Yod (

), representing Spirit, placed in the center of the name. Each letter of the Pentagrammaton signified a different type of magic known collectively as the Magic of Light. The five types of the Magic of Light are classified as follows: Evocations and invocations fall under the category of the Hebrew letter Yod (

) and the element of fire. Consecrations of Talismans and the production of natural phenomena are classified under the second letter Heh (

) and the element of fire. Consecrations of Talismans and the production of natural phenomena are classified under the second letter Heh (

) and the element of water. All works of spiritual development, invisibility, and transformations are attributed to the letter Shin (

) and the element of water. All works of spiritual development, invisibility, and transformations are attributed to the letter Shin (

) and the element of spirit. All works of divination are assigned to the letter Vav (

) and the element of spirit. All works of divination are assigned to the letter Vav (

) and the element of air. Finally, all works of alchemy are classified under the final letter Heh (

) and the element of air. Finally, all works of alchemy are classified under the final letter Heh (

) and the element of earth.6

) and the element of earth.6

Instead of complete ritual instructions, the Z.2 manuscript on the Magic of Light is largely composed of outlines for rituals meant to be fleshed out by each Adept working the system. In Book Six of The Golden Dawn, Regardie provided examples of rituals he had written based on some of the Z.2 outlines.7 He did not, however include a ritual based on the Heh Final (

) outline for alchemy. He gave his reasons for this:

) outline for alchemy. He gave his reasons for this:

The section on Alchemy remains quite obscure since the subject does not interest me; and I regret that I have not been able to acquire a record of an operation based on it. (N.B. Since this was written, my book entitled The Philosopher’s Stone has been published. It is a fairly protracted survey and analysis of alchemical ideology.—I. R.) 8

In addition to Regardie, many Golden Dawn practitioners through the years have been mystified by the “obscure” instructions given in the alchemy section of the Z.2 papers. We have always felt that this was unfortunate, since the Magic of Light as given in Regardie’s The Golden Dawn is the source of most of the personal ritual work and higher magic undertaken by Golden Dawn students. However, we were also certain that it would only be a matter of time before magicians who were skilled in practical alchemy would be able to unscramble the enigmatic ritual outline and provide clarity on how a Z.2 alchemical ritual could be performed. We are happy to report that this time has arrived, for three of the chapters in Book Five of this new edition of The Philosopher’s Stone have been contributed by practicing alchemists, specifically dealing with the Z.2 formula for alchemical theurgy.

By the time he wrote the Second Introduction to The Golden Dawn in 1968, Regardie’s interaction with Frater Albertus and the Paracelsus Research Society caused him to change his opinion about practical alchemy.9 By the 1970s Regardie was also conducting his own alchemical experiments in a small laboratory setting. In the HOGD archives there are a number of typed and hand-written papers outlining instructions for alchemical workings—papers with titles such as “Preparation of the Cerussite,” “Vegetable Stone,” “To Obtain Purified Tartar,” “To Extract Oil of Egg with ‘Angel Water’.” “Butter of Antimony,” and the like. However Regardie’s alchemical experiences also provide us with an important cautionary tale which no practicing alchemist should fall to heed: one of his experiments went awry and he seriously burned his lungs when fumes of antimony escaped in the lab. After this Regardie developed emphysema; he gave his alchemy equipment to a friend and for the rest of his life he suffered from the effects of the accident.10

Therefore Lesson Number One with regard to any work of practical alchemy is “Safety First!” Lesson Number Two is “See Lesson Number One …” The same goes for Lesson Number Three. No one, absolutely no one, should begin any work of practical alchemy under any circumstances without fully knowing and fully utilizing all possible safety precautions. This includes a comprehensive knowledge of the safe use of laboratory equipment as well as safety equipment, and a thorough and complete knowledge of the properties of all substances to be worked on. Important notes on safety is presented in “Book Five: Appendix Two” of this text.

Those familiar with earlier editions of this book will notice a difference in the spellings of certain words in Hebrew (such as Sephiros in place of Sephiroth, Keser for Kether, Daas for Daath, Tipharas for Tiphareth, Malkus for Malkuth, etc.). This variance in Regardie’s spelling of these words was due to a difference in dialect—Askenazic Hebrew versus Sephardic Hebrew. Regardie’s early works, including The Philosopher’s Stone, featured the Askenazic dialect, a form of Hebrew pronunciation used in central Europe, wherein the Hebrew letter Tau or Tav is sometimes pronounced as an “s.” Later in his career, Regardie adopted the more common Mediterranean Sephardic dialect used by many Qabalistic authors, translators, and the majority of hermetic students. Since most Golden Dawn magicians practicing today use the Sephardic version, we have changed the spelling of the words mentioned above to reflect the more familiar modern usage.

The illustrations from previous editions have been redrawn, and additional alchemical graphics have been added. Unless otherwise indicated, all footnotes are ours.

In this new annotated edition of The Philosopher’s Stone, the entirety of Regardie’sseminal textis contained in the sections entitled “Book One,” “Book Two,” and “Book Three.” We have added explanatory titles to the “Book” sections in order to help readers have a better understanding of what is contained in them. These are preceded by Regardie’s “Chapter One: Introduction” (to alchemy) and his “Introduction to the Second Edition,” which was added in 1968. A description of the various sections and chapters of this edition follows:

BOOK ONE: Alchemy, Psychology, and Qabalah—

Chapter Two contains the full text of “The Golden Treatise of Hermes Trismegistus, concerning the Physical Secret of the Philosopher’s Stone. In Seven Sections.” This was one of the texts found in Atwood’s A Suggestive Inquiry into the Hermetic Mystery.

Chapter Three contains Regardie’s Commentary on the “Golden Treatise” using the language and principles of Jungian psychology and the Qabalistic Sephiroth to explain the symbolism of the First Matter, the Elements, the Quintessence, the Vine of the Wise, the Purified Stone, the Red Lion, the Flying Volatile, the Elixir of Life, the Dragon, etc. For example: “A vast amount of material exists in early psychoanalytical literature on the subject and significance of the Dragon. A great deal of this is well synthesized in The Psychology of the Unconscious by Jung … Our present text states that all the principles of man are polluted by the Dragon—by an anxiety and fear-laden Unconscious … our text advises us what to do. A dissolution of the entire emotional and mental nature is to be achieved before we can proceed …”

Chapter Four is a continuation of Regardie’s discussion on the meaning of the symbolism contained in the “Golden Treatise.”

BOOK TWO: Magnetism and Magic—

Chapter Five serves as an introduction to the Magnetic Theory and Mesmerism which are discussed in detail. Both imply a system of healing through the manipulation of subtle energies such as prana life force energy and the astral light.

Another alchemical treatise printed in Atwood’s book is provided in Chapter Six. This is “The Six Keys of Eudoxus, opening into the most Secret Philosophy.” Regardie’s analysis of this text is given in Chapter Seven. Here Regardie finds agreement with Atwood’s hypothesis that the underlying importance of prana magnetism and its relation to higher states of consciousness are the true secrets sheathed in the symbolism of alchemy.

In Chapter Eight: The Magical View, Regardie compares the workings of the Golden Dawn initiatory system to the various stages of alchemy. One of the goals of the system is integration.

BOOK THREE: The Mystic Core—

Chapter Nine contains the full text of Thomas Vaughan’s “Coelum Terrae, Or The Magician’s Heavenly Chaos.” Although this tract is not found in Atwood, Regardie included it as a fine example of alchemical writing. Regardie’s brief commentary on the tract and his concluding remarks are contained in Chapter Ten. This chapter marks the end of Regardie’s original text.

BOOK FOUR: Practical Alchemy, Spiritual Alchemy and Ritual Magic—

The second half of this present edition is comprised of new material; rituals and essays written by contemporary authors and alchemists. Chapter Eleven contains an essay titled “The Spiritual Alchemy of the Golden Dawn,” which continues the discussion on spiritual alchemy and examines the similarities between psychology and the grade ceremonies of the Golden Dawn.

Chapter Twelve contains the essay “Intro to Alchemy: A Golden Dawn Perspective” by author and practicing alchemist Mark Stavish, who presents the basics of laboratory alchemy in addition to commentaries on the Z.2 ritual outline for Golden Dawn alchemy.

Chapter Thirteen includes the paper “Basic Alchemy for Golden Dawn” by Samuel Scarborough, which provides an insightful look at laboratory alchemy.

Scarborough blends spiritual alchemy with practical alchemy in Chapter Fourteen: “Golden Dawn Ritual Method and Alchemy.” This article takes another look at the enigmatic ritual alchemy outline from the Golden Dawn’s Z.2 instructions on the Magic of Light. The author also includes a Z.2-based alchemical ritual for charging a tincture of Jupiter.

Another ritual based on the Golden Dawn’s Z.2 formula is Steven Marshall’s “The Elixir of the Sun: A Ritual of Alchemy,” provided in Chapter Fifteen.

Chapter Sixteen contains our own alchemical ritual entitled “Solve et Coagula: The Wedding of Sol and Luna.”

BOOK FIVE: Resources—

The remaining section of the book contains helpful information such as a suggested reading list, safety tips, a glossary of alchemical terms, a biographical dictionary, and an index.

_____

Alchemy has received a lot of bad press over the years. Many people still regard it as either a pseudo-science of the ignorant or an enterprise set up by con-artists and frauds looking to dupe people into paying them to turn lead into gold. And yet in esoteric circles alchemy is currently enjoying a renaissance of interest. This interest extends to practical alchemy as well as spiritual alchemy. Pioneering organizations such as Paracelsus College and the Philosophers of Nature have been extremely influential in teaching the current generation of alchemists and their students.

From the time that Regardie first gained amazing insights into spiritual alchemy through Atwood’s writings to his later revelations concerning practical alchemy, Regardie was a firm advocate of the Hermetic Art:

The alchemists of olden time were spiritually enlightened—not merely blind and stupid workers or seekers in the chemistry laboratory. This fact must never be forgotten. They sought to perfect all phases of man—his body, his mind, and his spirit. No one of these aspects of the total organism should be neglected.11

The Philosopher’s Stone in its original form remains a classic text and a masterpiece on the processes and language of spiritual growth. We feel that Regardie would have been pleased with the additional material contributed to this present edition. In this regard we are determined to take his words to heart, and not neglect an important aspect of the total alchemical tradition.

—Chic Cicero and Sandra Tabatha Cicero

Metatron House

Summer Solstice 2012

INTRODUCTION TO

THE SECOND EDITION

During the winter of 1936–37, while living in London, I came down with a severe cold which proved intractable to treatment. My respiratory tract had become sensitized in early childhood by a bout of bilateral bronchial pneumonia. The result was that I was confined to bed for two weeks.

Instead of the usual mystery and detective stories recommended for such situations, my reading companion was Mrs. Atwood’s Suggestive Inquiry into the Hermetic Mystery.12 For years I had struggled vainly with this large tome, annoyed continually by its obscurantism and pompous literary style that was almost as bad as A. E. Waite’s, but I had never really managed to comprehend her presentation of Alchemy. Now, bedridden, I was determined to give her book one final perusal. If, then, it still yielded nothing for me, I proposed to discard it along with some other books which had outlived their usefulness in my life. So, with notebook and pencil by my side in bed, I began casually to glance through Mrs. Atwood’s book, underlining a significant passage here and there, and jotting down some brief notes on the pad.

Suddenly, and to my utter amazement, the whole enigma became crystal clear and alive. The formerly mysterious Golden Tractate of Hermes and The Six Keys of Eudoxus seemed all at once to open up to unfold their meaning. Feverishly I wrote. In effect, the greater part of The Philosopher’s Stone got written in those two weeks of bronchitis. It is true that later I added some diagrams together with a short commentary to Vaughan’s alchemical text, and a few quotations from Carl G. Jung and other authors whose works were not immediately available while I was confined to bed. But actually the main body of the book was composed there and then.

My book has been praised as a good, meaningful book by some reviewers and by many readers, to judge from the mail I have received during the past thirty years. It is patently an open sesame to one level of interpretation. The Occult Review, now defunct, published a critical review by Archibald Cockren who took me rather severely to task for asserting that alchemical texts should be interpreted solely in terms of psychological and mystical terms. He himself, I subsequently discovered, had written a book Alchemy Rediscovered and Restored.13 Of course I immediately procured a copy. Since I was peeved by his review, I did not feel that his book had very much to offer—so I dismissed both offhand. I was about to write the editor of The Occult Review a scorching letter, but reason intervened so that fortunately it never got written.

The opportunity is rarely given to an author in his lifetime “to eat crow” and to enjoy it. This lot, it pleases me to say, is mine—after thirty years. Not that I would significantly change much of what I wrote then. I admitted that I had not “proceeded to the praxis” but I felt then and still do that a mystical and psychological interpretation of some alchemical texts was legitimate. There is unequivocally this aspect of the subject. Certainly Jacob Boehme and Henry Khunrath, for example, cannot be interpreted except in these terms.

Nor should one be permitted to forget some of the preliminary provisions laid down by Basil Valentine in The Triumphant Chariot of Antimony:

This object I pursue not only for the honour and glory of the Divine Majesty, but also in order that men may render to God implicit obedience in all things.

I have found that in this Meditation there are five principal heads, which must be diligently considered, as much are in possession of the wisdom of philosophy as by all who aspire after that wisdom which is attained in our art. The first is the invocation of God; the second, the contemplation of Nature; the third, true preparation; the fourth, the way of using; the fifth, the use and profit. He who does not carefully attend to these points will never be included among real Alchemists, or be numbered among the perfect professors of the Spagyric science. Therefore we will treat of them in their proper order as lucidly and succinctly as we can, in order that the careful and studious operator may be enabled to perform our Magistery in the right way.14

It is evident then that though some alchemists did work manually in a chemical laboratory, they were at the same time men of the highest spiritual aspirations. For them, the Stone was not only tangible evidence of successful metallic transmutation; it was accompanied by an equivalent spiritual transmutatory process.

My readers will know by now that my thinking on most of these occult subjects had been profoundly influenced by the life and work of Aleister Crowley. So far as his knowledge of Alchemy went, I ought to narrate that in the winter of 1897, he had gone to Switzerland for mountain-climbing and winter sports. While there he encountered a Julian Baker, with whom he had a long conversation about Alchemy. This indicates at the very least that Crowley had been widely reading on this topic as well as on mysticism. As a result of this conversation, Baker promised to introduce Crowley to a chemist in London, George Cecil Jones who might be instrumental in getting him admitted into the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. There is not the least shred of evidence to indicate that Crowley, Baker or Jones had done any practical laboratory work in Alchemy. In magic—yes; in Alchemy, no!

Many years later, Crowley came to use alchemical symbolism to elucidate the “Mass of the Holy Ghost,” the sex-magic principles of the O.T.O., principles that I re-stated in the 16th chapter of The Tree of Life.15

To refer back to the Golden Dawn, it seems to me that there was little that was really illuminating on Alchemy in its curriculum, though in other areas, particularly the magical, I feel today as I always have.

The Golden Dawn was essentially a Qabalistic and magical order, not an alchemical one. I do not know of any evidence pointing out that Mathers or Westcott had ever engaged in operating an alchemical laboratory. One document, bearing the imprimatur of Mathers, deals with Alchemy, not from the laboratory viewpoint, but from that of ritual magic—and at best it is plain verbiage.16 Its mystical interpretation is best expressed in a speech made by one Adept in its classic ritual: “In the alembic of thine heart, through the athanor of affliction, seek thou the True Stone of the Wise.”17

To this extent, the Golden Dawn had severed its traditional ties with the parent Rosicrucian bodies of Germany and Central Europe which were patently alchemical. One has only to glance casually through The Secret Symbols of the Rosicrucians18 to realize the extent to which Alchemy was considered the predominant feature in the Rosicrucian work of that era.

I know none of its members who could at any time have thrown any ray of light on Alchemy.19 One member, the late Capt. J. Langford Garstin, wrote a couple of books, Theurgy20 and The Secret Fire,21 about Alchemy, but they too yield little of practical value on the subject. I have met people here and there in the past forty years who could talk about Alchemy, but I cannot say that any of them made much sense.

Events in the past few years—a Uranus cycle—have conspired to force upon me a thoroughgoing expansion or reorientation of my original point of view, so that I can now quite happily admit that Archibald Cockren was right.

How this came about is a story in itself—typical of the way in which such things occur. Through a friend of a friend of mine, I was introduced to Mr. Albert Riedel22 of Salt Lake City, Utah, while he was visiting Los Angeles. At the time I was domiciled there, enjoying the sunny climate and occasionally ruminating over the inclement weather of London where I was born. It took only a few minutes to realize that I was talking to the first person I had ever met who knew what he was talking about on the subject of Alchemy. We promised to keep in touch—and we did.

This promise later eventuated in an invitation to attend a seminar on Alchemy that he was conducting at the newly instituted Paracelsus Research Society in Salt Lake City. Most of the material presented in the Seminar concerned Alchemy, Qabalah, Astrology, etc.—with which I was already theoretically familiar—though even there some radically new and stimulating viewpoints were obtained. But the piece-de-resistance was the laboratory work. Here I was wholly dumbfounded.

It took no more than a few minutes to help me realize how presumptuous I had been to assert dogmatically that all Alchemy was psycho-spiritual. What I witnessed there, and have since repeated, has sufficed to enable me to state categorically that, in insisting solely on a mystical interpretation of Alchemy, I had done a grave disservice to the ancient sages and philosophers.

When Basil Valentine said, for example, in his work on antimony: “Take the best Hungarian Antimony … pulverize it as finely as possible, spread thinly on an earthenware dish (round or square) … place the dish on a calcinatory furnace over a coal fire …,” he means exactly what he says—exactly and literally. When he says a coal fire, he was not referring to the inner fire or Kundalini. It is simply ridiculous to assume he is talking in symbols which must be interpreted metaphysically, etc. Once you have followed his instructions to the letter, literally, or have been privileged to have seen this laboratory process demonstrated, then you know that “manually” is certainly not meant to be interpreted as by Mrs. Atwood in terms of mesmeric passes of the hands.

There is a more or less lengthy passage in Praxis Spagyrica Philosophica by Frater Albertus (Salt Lake City, 1966), which is worthy of quotation at this juncture. He wrote, in a footnote to page 77 et seq:

Some have gone to extreme pains to duplicate the ancient implements of former alchemists. They had to be able to obtain better, or at least for sure, the same results with our modern instruments. Take the regulation of heat alone. Formerly it was an arduous task requiring an assistant to keep the temperatures under control for the various manipulations. This expense alone was one that not many of the average persons could afford. To-day we have gas, natural or artificial, electricity and other means at our disposal giving us a much greater accuracy than was possible to obtain by manual operation. Vessels are stronger and not as fragile as formerly. Pyrex and similar glass containers can take much more heat and are in less danger of breaking. Stainless steel, another of the modern marvels, does away with the old copper still that had formerly many corrosive sublimates and other by-products when natural processes were followed …

Last, but not least, it should be remembered that many of the essential ingredients used had to be prepared by slow and sometimes hard manual operations. The required basic substances were not always as easily available as it appears. Great distances, and the necessary time involved, made it even more difficult. There was no air parcel post. Horse drawn wagons had to bring the goods that were not immediately available (sometimes from foreign countries). No telephone calls over greater distances, spanning continents, were available to make possible the information needed at a critical point … Despite all these and similar hardships they were able to accomplish what many in our days cannot do. Telephone and air travel not withstanding …23

Again, let me repeat, my analysis of the three alchemical texts of The Philosopher’s Stone is worth preserving. I am proud that Llewellyn Publications has seen fit to return it to print in a new edition. I should have rewritten parts of the book in order to incorporate what I have since discovered through the person and work of Frater Albertus Spagyricus, the nom de plume which he prefers to be known by, but I have decided to let it stand as it was first written.

It did represent the dawn of insight for me then, and it was the product of a genuine illumination, partial though it was, and outgrown it as I have today. As such I think it has the inherent right to continued existence in its original form. Moreover, it may prove useful to other students who have not yet discovered this point of view, which certainly is a valid one. They may be at the stage of growth I was in thirty years ago, where it could be of value. It needs merely to be supplemented by other reading of more recent vintage.24

In the meantime, The Philosopher’s Stone, with these preliminary comments, should answer a wide-felt need which has called forth this new edition. I hope, being in print once more, it will bring new light and knowledge and values to present-day students who may be still groping in the dark areas of the occult towards Alchemy, where a guiding hand needs to be extended.

So, to close this Introduction, I must use the ancient Rosicrucian greeting, and the close of a Golden Dawn ritual:

May what we have partaken here sustain us in our search for the Quintessence; the Stone of the Philosophers, True Wisdom and perfect Happiness, the Summum Bonum.

Valete, Fratres et Sorores

Roseae Rubeae et Aureae Crucis.

Benedictus Dominus Deus noster qui dedit nobis hoc signum.

Israel Regardie

Studio City, California

November 1, 1968

1. Atwood, Mary Anne. A Suggestive Inquiry into the Hermetic Mystery (London: Trelawney Saunders, 1850), 597.

2. An Interview with Israel Regardie, edited by Christopher S. Hyatt (Phoenix, AZ: Falcon Press, 1985), 141.

3. Ibid., 143.

4. See Regardie, The Golden Dawn, sixth edition (St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn, 1989), Book Five, 376–412. The various “Z Documents” described much of the Order’s higher workings, a good deal of which took place on an astral level.

5. Ibid., 376.

6. Ibid., 395–400.

7. Ibid., 401–450.

8. Ibid., 377.

9. My interest in alchemy was stimulated in 1983, when Regardie bought me a one- year subscription to Essentia, The Journal of Evolutionary Thought in Action published by Paracelsus College. Francis and I often discussed alchemy in relation to the teachings of the Golden Dawn. He felt that I would benefit from alchemical work and encouraged me to attend Paracelsus College in Salt Lake City, inviting me to stay with friends of his in Utah while I received training there. The magazine subscription was intended to whet my appetite, which it certainly did. To my great regret, I was not able to take time away from my business to take the course.—CC

10. Regardie suffered much of his life from respiratory illnesses. In one paper he writes that for some forty years he had been a heavy smoker of pipe tobacco: “I stoked it up first thing in the morning, and only took it out of my mouth in the evening or when going to bed.” He developed asthma in the 1930s and his two-week bout of bronchitis in 1936 is documented, as is an early childhood attack of “bilateral bronchial pneumonia,” in his Second Introduction to this book. In one paper describing his general medical history, Regardie wrote that in April of 1971 he accidently inhaled the gas given off by a friend’s work on stained glass, resulting in a trip to the hospital with “pulmonary congestion and fibrillation of the cardiac values.” While much of this may be accurate, it seems likely that the hospital episode was the result of the alchemical experiment gone wrong and the stained glass story may have been created afterward for the benefit of Regardie’s doctor. Because of Regardie’s medical history, he probably should not have attempted to perform practical alchemy.

11. An Interview with Israel Regardie, edited by Christopher S. Hyatt (Phoenix, AZ: Falcon Press, 1985), 141.

12. A Suggestive Inquiry into the Hermetic Mystery, with a Dissertation on the more celebrated of the Alchemical Philosophers being an attempt towards the recovery of the ancient experiment of nature (London: Trelawney Saunders, 1850).

13. Alchemy Rediscovered and Restored (originally published in 1941) can be found at: http://www.rexresearch.com/cockren/cochren.htm.

14. Valentinus, Basilius, The Triumphant Chariot of Antimony (Kessinger Publishing, 1992), 12–13. This book can also be found at http://www.levity.com/alchemy/antimony.html and at http://www.sacred-texts.com/alc/antimony.htm.

15. See Regardie, The Tree of Life: An Illustrated Study in Magic (St. Paul: Llewellyn Publications, 2001), 370–378.

16. Regardie is referring to the alchemical work under the Earthy Letter Heh-final in “Z2: The Formulae of the Magic of Light.” See Regardie, The Golden Dawn, sixth edition (St. Paul: Llewellyn Publications, 2002), 395–400.

17. Adeptus Minor Ceremony. See Regardie, The Golden Dawn, sixth edition (St. Paul: Llewellyn Publications, 2002), 236.

18. “A Brother of the Fraternity,” The Secret Symbols of the Rosicrucians of the 16th and 17th Centuries (Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing, 2010).

19. One member of the Golden Dawn who certainly did know quite a bit about laboratory alchemy was the Reverend William Ayton. See The Alchemist of the Golden Dawn: The Letters of the Revd W. A. Ayton to F. L. Gardner and Others 1886–1905, edited by Ellic Howe (Wellingborough, Northhamptonshire: The Aquarian Press, 1985).

20 . E. J. Langford-Garstin, Theurgy, or the Hermetic Practice: A Treatise on Spiritual Alchemy (Nicolas Hays, June 2004).

21. E. J. Langford-Garstin, The Secret Fire: An Alchemical Study (Rosicrucian Order of the Golden Dawn, March 19, 2009).

22. Dr. Albert Richard Riedel (1911–1984) was the real name of Frater Albertus Spagyricus, founder of the Paracelsus Research Society, which later became the Paracelsus College, founded in 1982. For more on Paracelsus College see http://homepages.ihug.com.au/~panopus/

23. Frater Albertus, Praxis Spagyrica Philosophica (York Beach, ME: Weiser Books, 1998).

24. See the Book List of Alchemical Resources in Appendix One.