There followed a tense few hours as the mice waited for an opportunity to march unseen into the Rose Cottage living room. Colonel Acorn and the Brigadier mounted guard at the gates of Nutmouse Hall, monitoring the constant comings and goings on the other side of the wall.

All afternoon, Aunt Ivy sat at the kitchen table, filing her nails and drinking a foul-smelling herbal tea. The children appeared at five o’clock to make some toast, and took it away without a plate. After that Mr. Mildew came and scavenged in the fridge, then retreated back upstairs with some canned ham and half a banana.

“Fascinating, isn’t it,” Colonel Acorn said, peering through the bars. “These human creatures don’t seem to sit down to meals like we do. They graze, like cows.” (Colonel Acorn and his wife lived behind the flour bins in the village shop, so he seldom saw humans in their domestic habitat.)

“Yes, most odd,” agreed the Brigadier. “But mine aren’t at all like that.” The Brigadier lived in the airing cupboard of a grand house on the other side of the village, and he was rather proud of his humans. They had dinner in a dining room, by candlelight, and they had a maid to wait on them. “I believe that some humans have higher standards than others,” he concluded thoughtfully.

The Colonel agreed this was probably true. And then they both held their noses as Aunt Ivy started smoking a menthol cigarette.

Back in Nutmouse Hall, the ranks were beginning to feel restless. They had been buoyed up by General Marchmouse’s speech, but two hours later they were still cooped up in the ballroom. Mrs. Marchmouse was scurrying among them, dispensing cups of cocoa, and as it warmed them up they felt more boisterous than ever.

“When can we be off, General?” was the constant cry, and the General wished he could answer. But there was nothing to do but wait. He checked his watch constantly. Five o’clock…six o’clock…seven o’clock, and still no go-ahead from the officers at the gate.

Eventually, shortly before nine, Colonel Acorn reappeared. “All clear, General,” he reported excitedly. “Aunt Ivy is in the bath; Mr. Mildew is in his study; and the children have gone to bed.”

The General turned to face the troops. “Arise!” he roared magnificently. “The time has come to show the enemy what we’re made of!” The mice at once scrabbled to their feet, and were briskly marched outside. Nutmeg and Mrs. Marchmouse stood in the hall, watching them go. A lieutenant brought up the rear and slammed the door shut behind them Then Nutmouse Hall suddenly felt terribly quiet and still.

A green felt cap lay on the flagstones in the hall, dropped by one of the school mice, but otherwise the army had left no trace of itself. Nutmeg felt a sudden forboding. Oh, please bring them all home safely, she prayed silently. Then, feeling a sharp chill, she went to replace the draft excluder by the front door.

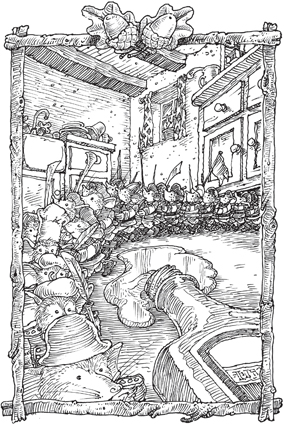

The kitchen light was off when the mice spilled out of the Nutmouses’ front gates, but the moon was shining through the window and it made their armbands glow. With the General leading, the army crossed the floor in a tight crocodile, making a detour around a pool of spilled tomato ketchup, and then crept into the hall. The General put a paw behind his ear; he could hear Aunt Ivy splashing about upstairs in the bath.

She had left the living room door open, and a soft reading lamp in the corner was casting long shadows across the floor. The room was cluttered, with lots of places to hide.

The sofa on which Aunt Ivy slept was on the far side of the room, in front of the window, and at either end of it there were coffee tables strewn with books and papers. There were armchairs on either side of the fire, and beside one of them a log basket full of old newspapers. On the opposite wall was the bookcase, so overladen that the shelves were beginning to sag in the middle, and heaped in front of it were all Aunt Ivy’s suitcases—one had a long green stocking snaking out of it.

Seeing the battlefield lying before them, the mice all felt a little awed. Every one of them knew, by instinct, that the thing to do when you saw a human was to run. But tonight they would be charging straight toward one, into hands that could squeeze them to pulp, and toward feet that could kick them so hard that they would go twirling and swirling into the air, until they smacked against a wall. Even the bravest among them felt his stomach flutter.

The General’s stomach was fluttering, too, but no one would have guessed it. “Officers, take up your positions!” he barked. Then he flicked his stick under his arm, clipped his heels together, and marched them forward.

Each officer knew where his platoon was to hide, and within five minutes they had all clambered into position. There were mice everywhere, even inside Aunt Ivy’s makeup bag, but they were so carefully hidden that there was not a mouse to be seen.

Keeping very still, they settled down to wait. It was a tense time for everyone, particularly for Colonel Acorn’s platoon, which had crawled through the tear in the lining on one of the sofa arms. They were hiding in the stuffing, which was thick and coarse; it got up their trousers and under their collars, itching mercilessly.

Things were more comfortable for General Marchmouse, who had hoisted himself onto the mantelpiece, where he was hidden behind a dusty potted plant.

From there, through his field glasses, he had watched the platoons take up their positions, and then, in the deep hush that followed, his sleepless night started to catch up with him, and his eyelids got heavier and heavier.

I must refresh myself before the battle, he thought, beginning to stagger slightly on his feet. He hated being tired, but since retiring he’d become increasingly prone to it. He drew his sword, and, reaching up, cut off one of the soft, green leaves fanning above his head. Then he lay down on it to rest. “Just a quick nap,” he said to himself drowsily, and within a few seconds he was fast asleep.

All around the room the eleven platoons crouched stiffly, waiting for the first scent of the enemy, and for the crack of General Marchmouse’s pistol signaling them to charge.

Eventually, after nearly an hour, they heard the thud, thud, thud of human feet on the stairs. They twitched their noses nervously, and picked up the scent of bathroom unguents. Then Aunt Ivy entered the room. The door made a loud creak as she pushed it to behind her, but not loud enough to wake the General, who was in a deep, deep sleep, dreaming of all the glorious battles he’d won in his youth.

The other two hundred and fourteen pairs of eyes all peeked out of their hideaways, wakeful and riveted. She was dressed in dark green pajamas with a red robe tied tightly at the waist, and she had on a thin gold bracelet and a necklace of fake pearls, each the size of a mouse’s head, and a silver lizard hanging decoratively from each ear. (Aunt Ivy always wore a lot of jewelry, even in bed.) The army felt uneasy; she wasn’t like the other humans in the village. There was something creepy about her, almost reptilian.

Aunt Ivy walked toward the window and tugged the curtains tighter together. The platoon on the sill cowered back into the shadows as one of her pink fingernails poked through the gap.

Then she walked toward the bookcase and started digging about in one of her suitcases. There was a platoon of mice hiding in the bottom of it, and one of them felt her finger brushing the back of his jacket. Eventually, she found what she was looking for, a tortoiseshell hand mirror and a pair of metal tweezers. She kicked off her slippers and lay back on the sofa, then started plucking the little gray hairs from her chin.

Aunt Ivy did this once a fortnight, and it was very tedious and fiddly. As she held the mirror up to her face she screwed up her eyes, stuck out her tongue, and stretched her legs right out, pressing her feet against the arm of the sofa. Her toes pushed Colonel Acorn’s platoon deeper into the stuffing, squashing the mice so tight that they could hardly breathe.

Why the devil doesn’t the General give the signal to charge? the Colonel wondered despairingly.

At that moment, Aunt Ivy’s big toe wriggled its way right through the hole in the lining, and he saw a gnarled toenail heading straight toward him. The Colonel squirmed, frantically trying to get out of its path, but he was trapped in the stuffing, barely able to move. The nail advanced on him like a tank.

He watched it loom nearer and nearer, dizzy with dread. And then, just as it was about to squash his nose, he opened his mouthand sank his teeth into Aunt Ivy’s skin. Chomp! He got her just below the toenail, and bit in so deep he had to wrestle his jaw free with his paws.

For a split second, nothing happened, and the Colonel wondered if he hadn’t dreamed the whole thing. But then there was a sudden shriek. “Fleas!” Aunt Ivy cursed, rubbing her toe, but she was about to face something much more alarming than that. For her cry had awoken the General, who was scrambling to his feet, frantically fumbling for his field glasses.

Standing beside the flowerpot, he quickly took stock of the battlefield. He saw the Brigadier peeking out from behind a botany encyclopedia on the bookshelf; he saw the glint of a sword in the log basket, and the soft glow of twelve fluorescent mice crouching up the chimney.

With adrenaline coursing from his head to his tail, the General rushed forward to the rim of the mantelpiece and fired his pistol in the air. The battle had commenced.