Tumtum and Nutmeg set out early next morning to collect the ballerinas. The milkman had not yet stirred, and the church spire was still shrouded in mist.

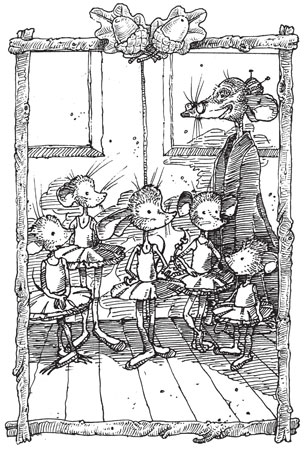

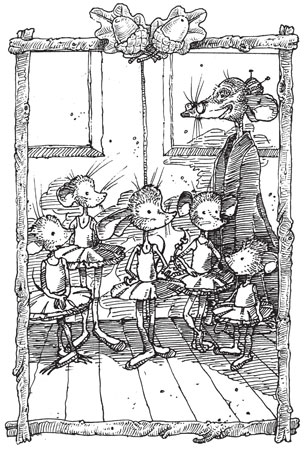

When they arrived in the vestry, they found Miss Tiptoe and her class waiting for them outside the cupboard. The girls were dressed in beige tutus, which had their names embroidered on them in silver thread. The Nutmouses studied them amoment so that they might remember who was who. There was Trixibelle, who had the long, beautiful ears…There was Millicent Millybobbette, who was the shortest…There was Lillyloop, who was the tallest…There was Horseradish, with the pink braids in her tail…and Tartare, with the sharp, silver toenails—

But it was no good. They could never remember so many names; just trying made their heads spin. And they were such odd names, too. In their day mice had been given simple names, like Nutmeg.

“You told me that the school had wooden floors, so I decided beige would be our best disguise,” Miss Tiptoe said. She had been up all night sewing.

“How clever of you,” Nutmeg replied. She suddenly felt embarrassed by the bright green cape she was wearing and wished she had dressed more discreetly.

Presently, the party set forth. They were a curious convoy, with the girls bouncing along like crickets on their pogo sticks, and Miss Tiptoe gliding elegantly beside them, while Tumtum and Nutmeg straggled in the rear with the picnic baskets.

The girls were in high spirits, and Horseradish shrieked when Tartare tried to bounce away with her earmuffs.

“Young ladies! Please recall that you are representing my ballet school!” Miss Tiptoe said sharply, and then they all looked a little chastened.

Before long they reached the school gates and saw the playground stretching before them. The girls all craned their necks as they looked up at the vast steel climbing frame. To them, it seemed as tall as a skyscraper.

“This way,” said Tumtum, leading the party toward the air vent. He pushed the pogo sticks through the grille first, then the mice climbed inside.

The ballerinas had never been in a school for human children, and the building felt cold and unfamiliar. They found something ominous about the huge shoes in the lockers and the enormous overalls hanging from the pegs on the wall. It was all so different from their own little school in the vestry.

They kept close together as they followed Tumtum under the door of ROOM 2B. It was dark, for the blinds were shut, and they couldn’t see as far as the cage. Everything was deathly quiet. “The prisoners must still be asleep,” Tumtum said, leading his party across the room.

“General! Gerbils! We’re back!” he called up from beneath the table. “Throw down the ladder!”

But there wasn’t a sound.

He called again, wondering why they didn’t reply. Then, blinking, Nutmeg let out a cry: “The cage! It’s gone!”

The Nutmouses stood motionless, stunned by this discovery. They couldn’t understand it. Miss Short had said that she was taking the gerbils to the pet shop on Saturday, but Saturday wasn’t until tomorrow.

“The cage must have been moved to another part of the school,” Tumtum said urgently. “We’ll search all the classrooms. Miss Tiptoe—you and your girls head down the corridor to your left, and look under every door. We’ll try the rooms to the right.”

The mice hurtled back out of ROOM 2B, and dispersed down the corridor, shouting the General’s name. Miss Tiptoe’s ballerinas bounced high and low around the gymnasium, the art room, and the kitchen. And the Nutmouses scuttled around ROOM 3A, and ROOM 1C, and all around the staff room, and the music room—but the cage was nowhere to be seen.

“He must have gone to the pet shop!” Nutmeg wailed. She had a sudden vision of Mrs. Marchmouse living the rest of her life alone in the big, rackety gun cupboard with no one to keep her company—and she started to weep.

“I will take my girls back to the vestry, since it seems there is no use for us here,” Miss Tiptoe said tactfully.

The subdued rescue party made its way back down the corridor toward the air vent. The girls walked quietly, pulling their pogo sticks behind them. None of them had met the General before, but the thought of any mouse being taken to a pet shop was enough to take all the bounce out of them.

But just as they were about to climb back outside, Tumtum suddenly stopped in his tracks. “What’s that?” he said, motioning the party to be still. They all stood quivering, their ears pricked. They could hear faint squeals.

“Over there! They’re in there!” Tumtum cried, pointing to the cupboard door across the corridor. Miss Tiptoe’s dancers had passed by it—they’d looked in all the classrooms, but they hadn’t thought of exploring the cupboards, too.

As Tumtum wriggled under the door, he could hear the gerbils howling. And rising above them was the voice of a most indignant General Marchmouse: “We’re here, you fools! Let us out! LET US OUT!”

“Where?” Tumtum shouted, fumbling for his flashlight. “It’s pitch-black. I can’t see a thing.”

“Here!” squeaked a dozen voices. “HERE!”

“Where?” Tumtum called again.

“Up here!” they chorused impatiently.

Tumtum craned his neck and shone his flashlight back and forth along the shelves. At first all he could see were cardboard boxes.

But then, on the lowest shelf off the ground he noticed a big lump covered with a filthy gray blanket. He shone his flashlight over it, trying to make out what it was. All of a sudden, the corner of the blanket tweaked, and the straw ladder came tumbling to the floor.

“Quick! I’ve found them!” Tumtum shouted under the door. The rest of the mice raced after him and they all clambered up to the prisoners.

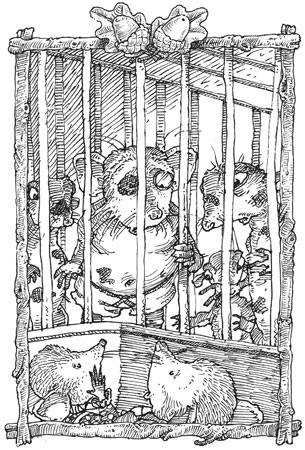

“Uncover us!” the General shouted furiously; and with the Nutmouses and Miss Tiptoe and the thirteen ballerinas pulling and tugging as one, they eventually managed to drag the blanket from the cage.

When Tumtum shone his light on the prisoners, it was clear that there had been quite a commotion. The exercise wheel had been snapped in two, and everyone was badly bruised. The General had a black eye and was in an especially ill humor.

“Why the devil didn’t you come back last night?” he asked furiously. “We’ve been sentenced to death, every last one of us!”

Each prisoner had a different version of what had happened, and everyone talked at once, so the story was rather hard to follow.

But it seemed that after Miss Short’s threat to transport them all to the vet, the General had become quite wild with anger. And when she’d picked up the cage he’d sunk his teeth deep into her finger—drawing blood, or biting it right off, depending whose account you believed.

Miss Short had then dropped the cage on the floor, and it had landed with a great crash, which is what had caused all the cuts and bruises and black eyes. She had shrieked a good deal, using words that had made the lady gerbils cover their ears— but the upshot was that she was too frightened to go near the cage again. And she had told the janitor that she would not take it in her car, nor did she want it to remain in ROOM 2B.

So the janitor had offered to get rid of it, saying that he would dispose of the gerbils over the weekend. Miss Short had not inquired how he intended to do this, but he had muttered something about having a friend who kept owls—and that had made all the prisoners quake, for they knew that owls liked nothing more than a succulent little mouse or gerbil to nibble.

And then the janitor had dumped them in the dark cupboard, out of Miss Short’s sight. He had thrown the blanket over them in order to muffle their protests, and left them to await their terrifying fate.

“The worst of it was thinking you’d never find us, Mrs. Nutmouse,” one of the gerbils said pitifully.

Nutmeg said nothing. For she was terrified that her plan might no longer work. It wouldn’t be nearly so easy now that the cage was in a cupboard instead of in the classroom. And besides, the janitor’s routine might have changed. There was no knowing what time he’d come and feed the gerbils now—or if he would come at all.

“Our plan will still succeed so long as everyone follows my commands to the letter,” the General said bossily, reading her thoughts. Then he looked at Tumtum and started giving orders.

“You and all the dancers must hide on the other side of the corridor, under the shoe lockers, until the janitor comes to feed us,” he said. “When he opens the door and removes the keys from his belt, I’ll give the order to hop. But nobody is to move until I issue it!”

“When do you think the janitor will come?” Tumtum asked.

“Oh, I don’t know!” the General snapped. “But if he wants to feed us to the owls, then it’s in his interest to fatten us up. I should think he’ll come soon enough.”

“Very good, General,” Tumtum said, looking at his watch. “We’d better hurry up and hide. It’s nearly eight o’clock and the school will be opening soon.”

“We’re starving!” one of the gerbils cried. “Did you bring us anything to eat?”

“Oh, I don’t think you’ll be short of things to eat,” Tumtum said, shining his flashlight over the labels on the cardboard boxes. “You’ve been locked up in the school’s candy cupboard!”