I played the stage, the Capitol,

And people said, “Don’t stop”;

Until you’ve played the Palace

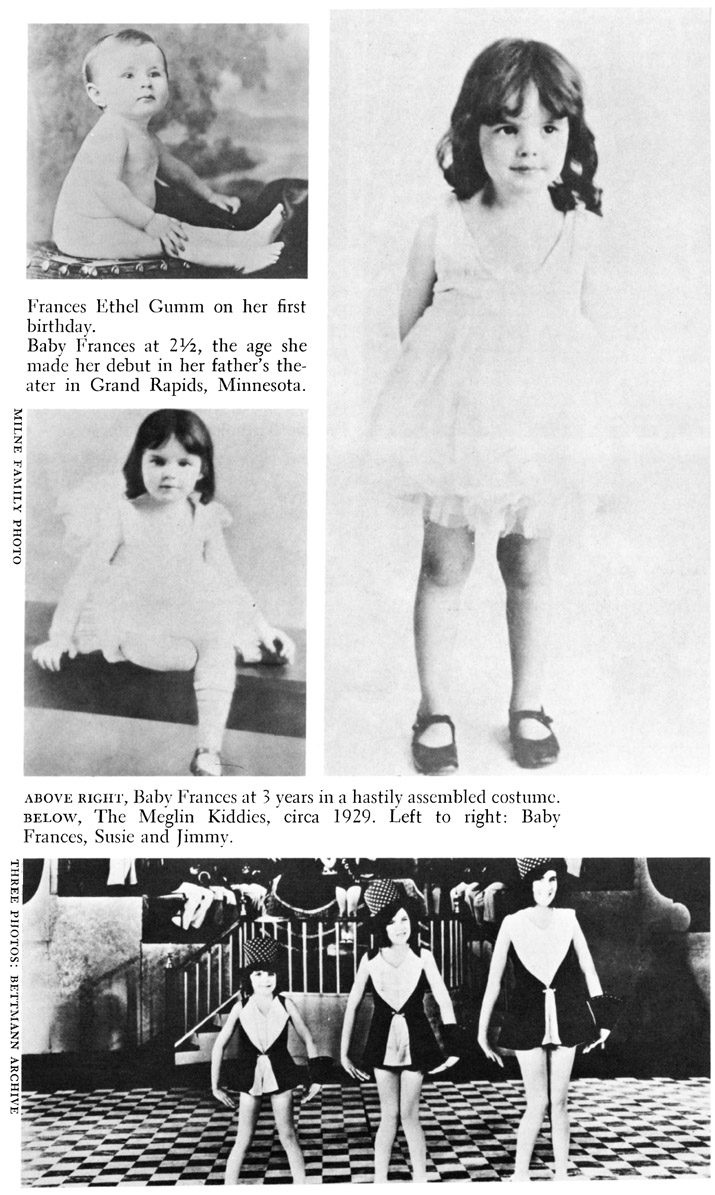

You haven’t played the top.

For years I had it preached to me,

And drummed into my head;

Unless you played the Palace,

You might as well be dead.

... it became the Hall of Fame—

The mecca of the trade;

When you had played the Palace,

You knew that you were made.

So I hope you’ll understand

My wondrous thrill;

‘Cause Vaudeville’s back at the Palace,

And I’m on the bill.

—Roger Edens

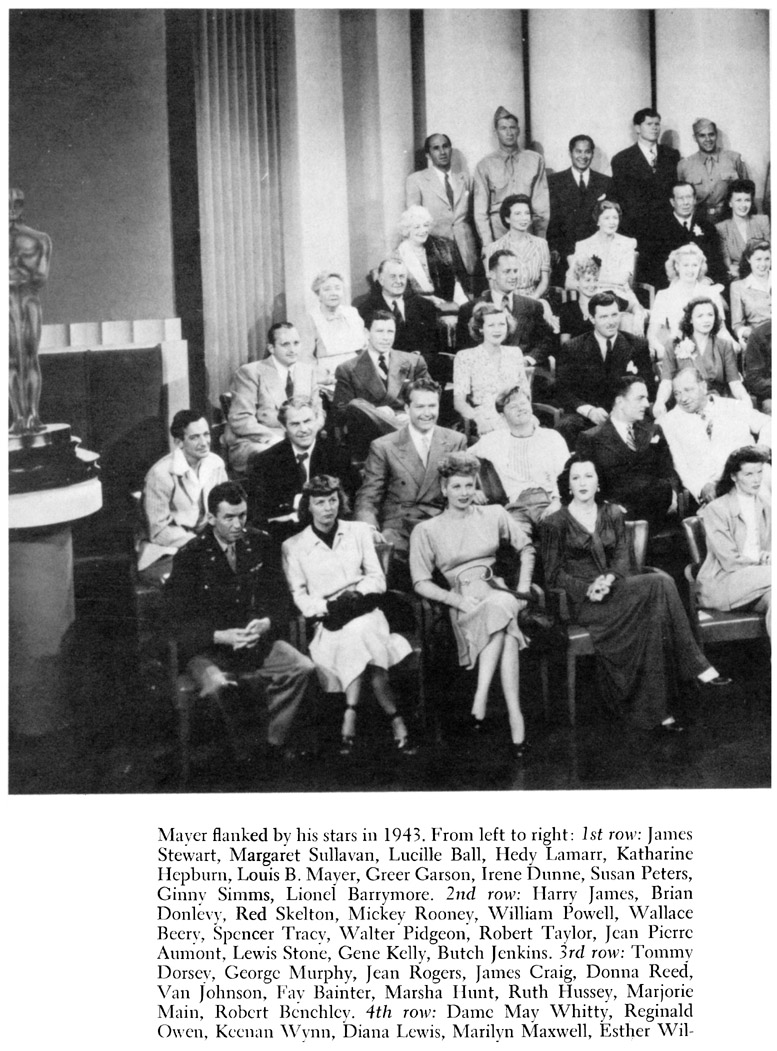

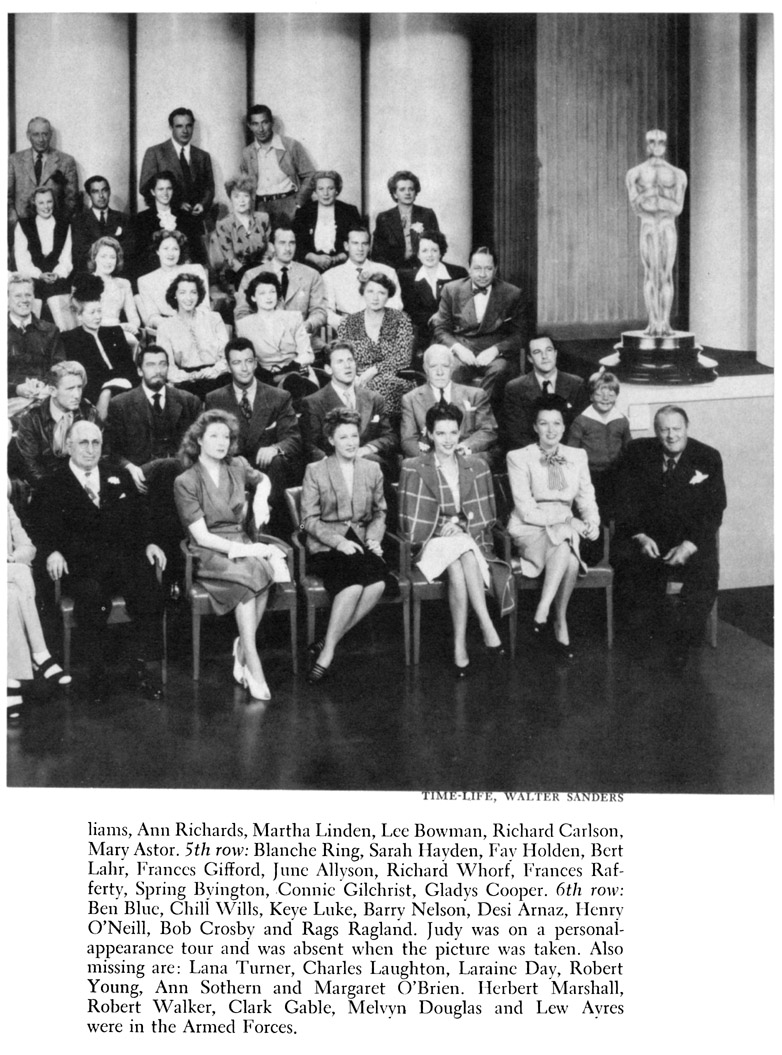

23At the beginning of her severance from Mayer and the studio, Judy felt like a displaced refugee. There seemed no place for her to go. Her film career appeared to be behind her. Summer Stock was yet to be released, and she knew her performance had been creditable; but word had passed from studio to studio; rumor spread by mouth to press—Garland was an untouchable. At her own studio she had been replaced by Leslie Caron, Jane Powell, and Debbie Reynolds. At Twentieth Century-Fox, Marilyn Monroe had startled audiences and awakened studio executives in The Asphalt Jungle and All About Eve.

Mayer’s loan was little more than what recently had constituted a week’s salary. Admittedly, that amount was above the national yearly income for a family of four, but that had to be placed in its proper perspective. Judy had never handled her own money—had no conception of the cost of things. Since achieving stardom at MGM, she had lived in the manner of royalty. Houses were showcases; clothes were specially designed, cars and chauffeurs ordered on demand; secretaries answered mail; maids cleaned; cooks commanded kitchens; children were in the hands of nursemaids; bills were paid by accountants; and you never saw the money you earned. What she knew was that in order to keep all these things in running order, she must perform nonstop. Now the mechanism had ground to a heavy halt.

Panic set in. She was broke. In a similar situation average people would, perhaps, move to a small apartment, tend house themselves, take any kind of job to tide them over. But Judy had no idea how to accomplish such a foreign way of living.

Instead, she moved into the Beverly Hills Hotel—possibly one of the most luxurious hotels in the world, but the one she was accustomed to visiting when close friends and business associates came to California. Her suite (she had Liza and a nursemaid with her) cost over $150 a day. She never thought to ask, however, how much it was costing her; and had she, it is doubtful that she would have known what else to do. One thing was obvious, though: Mayer’s loan would not last long with such a high standard of living.

Louella Parsons (in her book Tell It to Louella) stated: “I have heard it said that much that happened to Judy was the fault of Hollywood. I can’t agree. I can only say, however, that it could only have happened in Hollywood.”

Hollywood citizenry is not notable for a sense of loyalty. Riven, at the time, by mushrooming clouds of McCarthyism, Hollywood trembled in fear. Pink subpoenae were being received at the most famous houses, commanding their occupants to appear before The Committee. But those who did not receive subpoenae were not free and clear; they could be guilty by association. It was an economic condition that the Hollywood elite had always had to survive. To be connected with a film that failed, a falling star, a has-been director could mean the taint would rub off on anyone too close. That is why there were during those years so many “comebacks” in Hollywood. One bad film and you were reduced to the status of “has-been.”

With that fear always hanging over their heads, members of the industry who had a free choice, could not afford the risk of hiring a star who might crack up at any moment and throw their budget or film into chaos. Judy was fully aware of her position. In some ways, she accepted this harsh truth with a sense of relief. Appearing before the cameras was unthinkable. She was sick and exhausted. For days she never got out of her hotel room. Then she was presented with her first weekly bill. The same anxieties and terrors as when she had seen her hospital bills grasped her, and Mayer’s loan was running out.

To further complicate her situation, she was without representation. She had, the last few years, been represented by the Berg-Allenberg Agency, but Phil Berg and Burt Allenberg had split. Berg, whose private client she was, no longer had an association with the office. Had she been a winner at that time, there is no question that Allenberg would have held tenaciously on to her agency commitment. It would seem, however, that no matter how reluctant he was in moral attitude to walk away from her, his business acumen won out.

Most plaudits have gone to Sid Luft, who was to be her future husband, and Abe Lastfogel, of the William Morris Agency, who would finally come to represent her, for starting Judy out on a new career—the concert stage. But in fact, it was Ethel who was responsible for the second phenomenon of stardom in her daughter’s life.

Now divorced from Gilmore, Ethel rushed to Judy’s side. Whatever her motive, whatever enmity had been between them, however complex Ethel’s reappearance in Judy’s life and Judy’s acceptance of that presence—each now desperately needed the other, and neither had anyone else to turn to. True, Ethel had two other daughters, but they had gone their own ways: Sue marrying bandleader Jack Cathcart and living in Las Vegas; Jimmy now married to Thomas Thompson and residing in Dallas. One of Ethel’s sisters, Norma, did live in Hollywood and was, in fact, struggling to make a career for herself as a singer. Married to a stunt man and fighting Judy’s image (her voice had a distinct Garland ring to it), Norma did not seem to Ethel to have a real future. Except for one brother, Frank Milne, the other close members of her large family were not part of the entertainment world, and as Frank was a gambler, Ethel did not approve of him and was always angry when Judy advanced him money. Ethel, not prepared yet to go it alone, turned to Judy.

It seemed perfectly clear to Ethel that since Judy had started on a stage with a live audience, she could begin again there. Convincing Judy that cabaret or theater exposure would not be as demanding as films, Ethel then had to set about, as she once had, to find an engagement. She never had to persuade Judy of the financial necessity of her working. Judy was almost too much aware of the fact, and it pained her gravely. Minnelli was not inclined, nor could he afford, to maintain a standard of accustomed living for them both individually.

Having been out of the business for years, Ethel could only hope to tap familiar and old haunts. She went to the Cal-Neva Lodge; and though the terms of that contract aren’t known, the fee Ethel was to receive was reported as fair and satisfactory. The two women then went to Roger Edens, who helped them put together an act. (This was fundamentally the same act that Judy later took to the Palladium.)

By the time Judy arrived at Cal-Neva Lodge, Summer Stock had previewed. After viewing it at a private showing, Billy Rose was prompted to write her an open letter in his syndicated column, Pitching Horseshoes, titling the letter “Love Letter to a National Asset” and addressing it to Judy at the Cal-Neva Lodge, Lake Tahoe, California. Rose (who had once been married to Fanny Brice) wrote in part:

I found your portrayal of a farm girl in “Summer Stock” as convincing as a twenty-dollar gold piece, and when you leveled on Harold Arlen’s old song, “Get Happy”—well, it was Al Jolson in lace panties, Maurice Chevalier in opera pumps! . . . Naturally you’re wondering why I’m taking heart in ball-pen and writing you this love-and-kudos letter right out in the open. Well, like everyone else, I read the front-page stories about you a couple of months back, and from the lines between the lines I sensed that you had been having a bout with the jim-jams yourself, and that you no longer cared much whether school kept or not. . . .

This letter—and I know it’s plenty presumptuous—is to point out, in case you haven’t thought of it yourself, how important it is to millions of people in this country that school continue to keep for Judy Garland. ... It gets down to this, Judy: In an oblique and daffy sort of way, you are as much a national asset as our coal reserves—both of you help warm up our insides.

The letter was signed “Your devoted fan, Billy Rose.”

All the principals in the Cal-Neva plan to present Judy Garland for the first time in a supper club are now dead, and with them died the explanation of why Judy never did honor that contract. She remained at the Lodge for several weeks at their expense and worked on musical arrangements with Roger Edens. But then she abruptly left and returned to the Beverly Hills Hotel, now checking into a seven-room suite, which included connecting rooms for Ethel; for a secretary, Myrtle Tully; and for Liza and her nursemaid. Judy then proceeded to indulge herself in an eating binge that within a very short time added an additional thirty pounds to her five-foot-two-inch frame.

Now, answerable only to herself, she was flaunting Hollywood and all the demands and restrictions being a film star had imposed. When her hair once again began to fall out, she clipped it short and wore it in a boyish style; and taking what little money remained, she bought an air ticket to New York, moving Liza and the nursemaid back to Minnelli’s care and sending Ethel to stay with Norma. The hotel was told to send the bill to her agents, Berg and Allenberg, although they no longer represented her.

In New York she checked into a luxury hotel, devoured almost every dish on the Room Service menu, walked all over Manhattan, and cheered New York to win over Philadelphia in the 1950 World Series. Friends extended her loans which enabled her to survive, but it was her exposure to the crowds of people who grasped her hands, the contact with fans who appeared to love and care for her that kept her alive.

She became exceptionally heavy. The joy, the ecstasy of her new personal freedom faded fast. The hotel bill was ballooning as quickly as she was. Anxiety riddled her body, stirring her into constant wakefulness; and there was not the pill availability she had had in California.

Plump, matronly-looking, on edge, she attended a cocktail party and at it met Michael Sidney Luft. Later she claimed it was love at first sight. Perhaps, but it is more likely that she simply responded to his flattering male attention, which had not been coming her way for a long time. Always a romantic, Judy needed romance in her life now more than ever before to help her reestablish her sense of “womanliness”; it is therefore, not difficult to understand Luft’s appeal for her.

He did not stand in judgment of anything she did. He was a rebellious spirit, rootless, and without any specific talent or trade. Born in New Rochelle, Luft had grown up in Bronxville, New York, and had attended the Hun School in Princeton, the University of Pennsylvania, and the University of Miami. Athletically inclined as a young man, he had always been a glib talker and a bit of a show-off. He came from a small middle-class Jewish family, and he seemed able to break ties quite early. At the age of nineteen he was living on his own in Ottawa, Canada, where he was involved in the production of an Aquacade. It was his first taste of professional show business, and it made a strong impression on him. On future records he claimed that in 1940 he had joined the Royal Canadian Air Force and that once discharged, he had traveled to Hollywood. In Hollywood he looked up an old schoolmate from Bronxville, dancer Eleanor Powell, who was then a star, and for a time was her secretary.

After that, records state he was a Douglas test pilot and a technical adviser on the flying sequences of a low-budget film called Charter Pilot The film was what was then called a “programmer”—meaning it was to be booked as the bottom half of a double feature. In it was actress Lynn Bari, known at the time as the Queen of the “B’s.” Luft married her and immediately stepped in to take over her career. His intention was to promote an independent film with himself as producer and Miss Bari as star. A lovely-looking lady, a reliable performer, and a popular supporting player, Miss Bari, unfortunately, did not have the charisma on which stars and independent films are banked, and so for eight years Luft floundered through a marriage in which his wife was the bigger wage earner—but through no business acumen attributable to him.

Broad-shouldered, bedroom-eyed, easy-mannered, Luft had a freewheeling, unrestrained attitude that had a special charm for Judy. It was new; it was exciting; and there was a sense of surprise at her own attraction to him. He was not at all like her previous husbands.

She returned to Los Angeles, and Luft followed. Neither had a job, and both were involved in divorce actions. They saw each other constantly, and what he said, coupled with Ethel’s initial push, nagged at her. In essence, it was “The hell with films—why not the stage?” And if the stage—why not the Palace? He also suggested he manage her career. But Judy still had too much respect for the Hollywood “system” and was inclined to believe she needed a strong and well-established Hollywood agency. She went to Phil Berg, who was now with Abe Last-fogel at William Morris. Berg discussed it with Abe and they met with Judy. The next day the new alliance was announced in Variety:

Hollywood, October 10 [1950]:

Judy Garland signed an agency deal with the William Morris office, which will function hereafter as her representatives [sic] in all phases of show business. First move will be to set up guest shots on radio, but the star will not be available for T.V. work “for the time being.”

In the same issue of Variety was an announcement that “finally free” from her Metro contract, Judy Garland was “back in harness.” There was mention of the possibility of her replacing Mary Martin in South Pacific, recording two Decca albums, and/or doing a film or stage musical version of Booth Tarkington’s Alice Adams for Jerry Wald and Norman Krasna at RKO. But the most significant item in the short article mentioned talk of a late-January European trip.

Judy discussed the idea of her giving a concert at the Palace with Abe Lastfogel. Lastfogel did not laugh at her—which she was afraid he might. He did, however, discuss the advisability of trying out the act first before reaching New York. He asked, “Why not the Palladium in London?” Judy replied, “Why not?” but she never gave it serious consideration.

All talk of film and stage activity soon faded. She did record an album and appear on eight radio shows with Bing Crosby and in a Lux Radio Theatre adaptation of Easter Parade. It was just enough work to keep the wolves away from their door —“their” implying Luft and herself. Luft was now acting as her business manager and handling all incoming revenue. It could not have been an easy task, for Judy still had a mountain of debts, including moneys owed the Government for back taxes.

During her CBS radio performance of Easter Parade, there was an incident that on the surface might have seemed rather unspectacular in the life of a famous person. She met a devoted fan, a man named Wayne Martin who for fourteen years had submerged his own personal life into a total and vicarious absorption in Judy’s life and career. A thoughtful, quiet, semi-scholarly man, he had been a loner much of his life, living in a Hollywood apartment that was a jumble of Garland “artifacts": records; clippings; pictures; a few letters from Judy, signed to him in “her left-handed longhand.” Wayne Martin was no teen-ager, romantic boy, or shy Romeo. Asked to define his fanatic dedication, which persisted and was constant through the years that followed that first meeting, Martin was quoted as saying, “As soon as the overture starts, a feeling comes over the whole audience—the anticipation and the love. When she sings, there’s a cry from her being. People want to help her.”

The Garland Cult had surfaced.

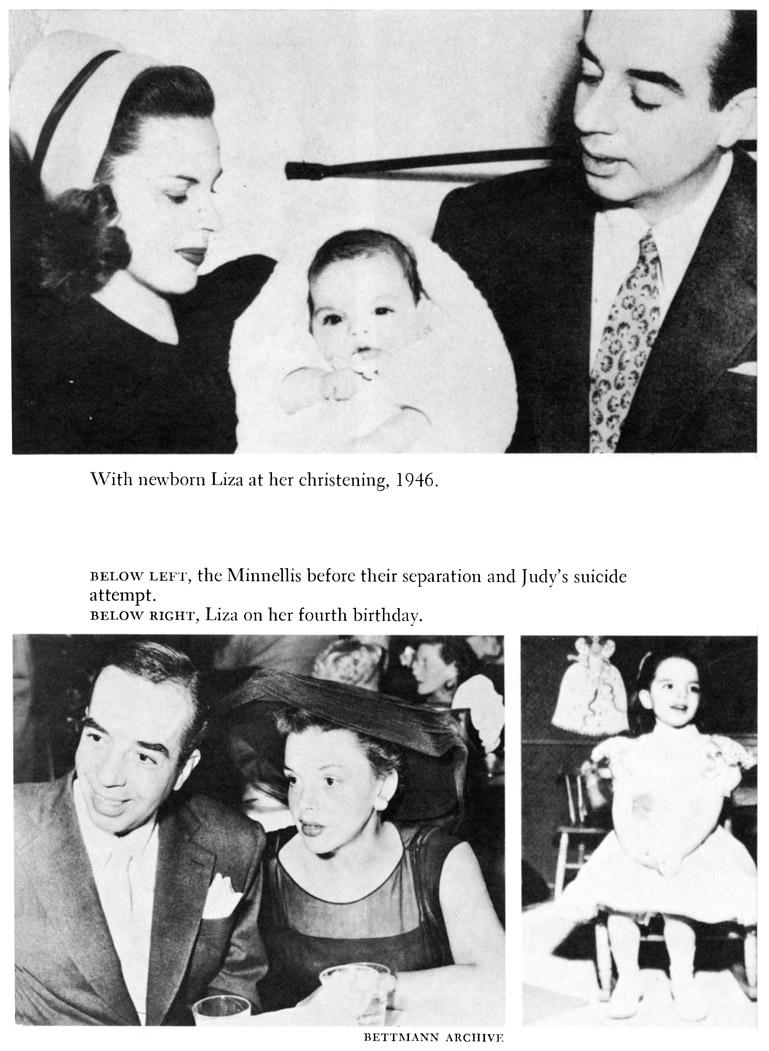

24Liza, speaking to a Time interviewer from the floor of her apartment as she hugged her dog and smoked cigarettes, talked about the years with Luft and her mother. “We started moving around a lot from one house to another. Usually we moved in the night. That was probably because Mama was so broke and maybe she owed money to landlords. Anyway, every time we moved, I’d find myself in a different school. Private, if we could afford it; public, if we couldn’t. As a result, I hated school.”

And speaking to Stephen K. Oberbeck of Good Housekeeping magazine, she recalls, “When Mama was down in the dumps, I’d say, ‘Come on, Mama, let’s go to the park and ride the roller coaster.’“

This wasn’t the life Judy had wanted for Liza. She would have had it another way if it were possible. Money always seemed the key. She had worked all her life, and there wasn’t anything there for Liza’s security and future. Luft promised her he could change all this, and she believed him because she wanted desperately to do so.

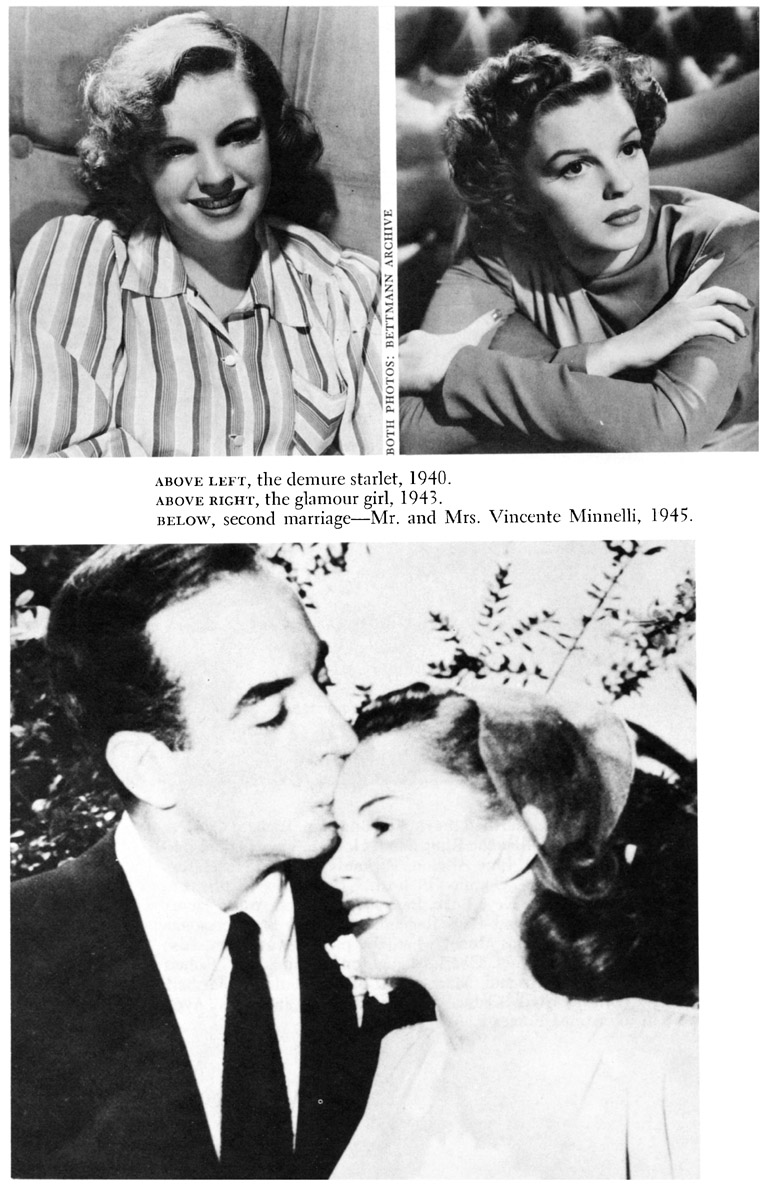

On March 23, 1951, she went into court to obtain her divorce from Minnelli, charging mental cruelty and telling Judge McKay from the witness stand in a slow, deliberate voice, “He [Minnelli] secluded himself and he wouldn’t explain why he left me alone so much.”

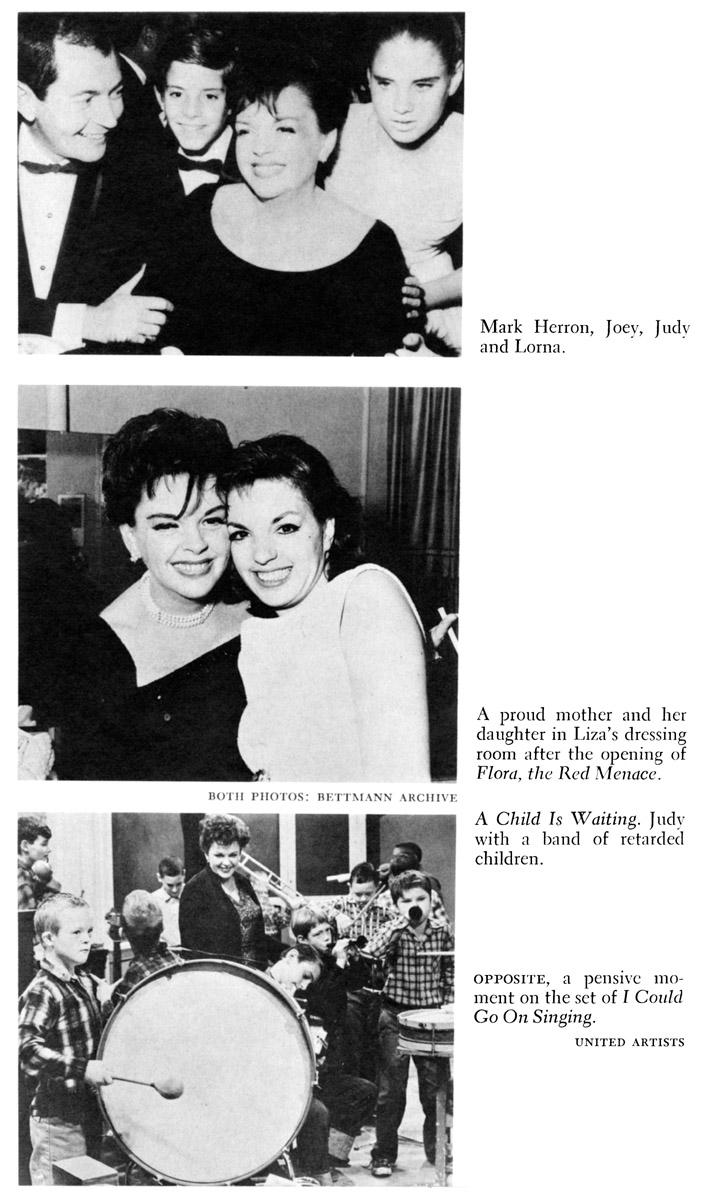

Even for Hollywood, the provisions for Liza were most unusual. Judy was to have legal custody, but the child would spend six months each year with each parent. However, in the words of the pact, “.. . The child will be given utmost ‘freedom of locomotion’ and changes from one home to the other will be irregular to avoid the child developing a feeling of regimentation.”

Whatever differences Judy and Minnelli had had in the past, it seems he knew that Judy adored Liza and that Liza loved her mother, and that the bond between them was far more important than the rigors Liza might suffer or the circumstances she could possibly be exposed to in spending six months with Judy.

Certainly there was little chance of the child’s becoming “regimented.” She was catapulted from mother to father, from one extreme to the other. Minnelli remained in Hollywood, living out the Hollywood success syndrome, remarrying a socialite, running a formalized home, and attending and giving glittering parties. His wife, Denise, lived in a world of couturier clothes, “in” restaurants, “acceptable” people, and current fashions.

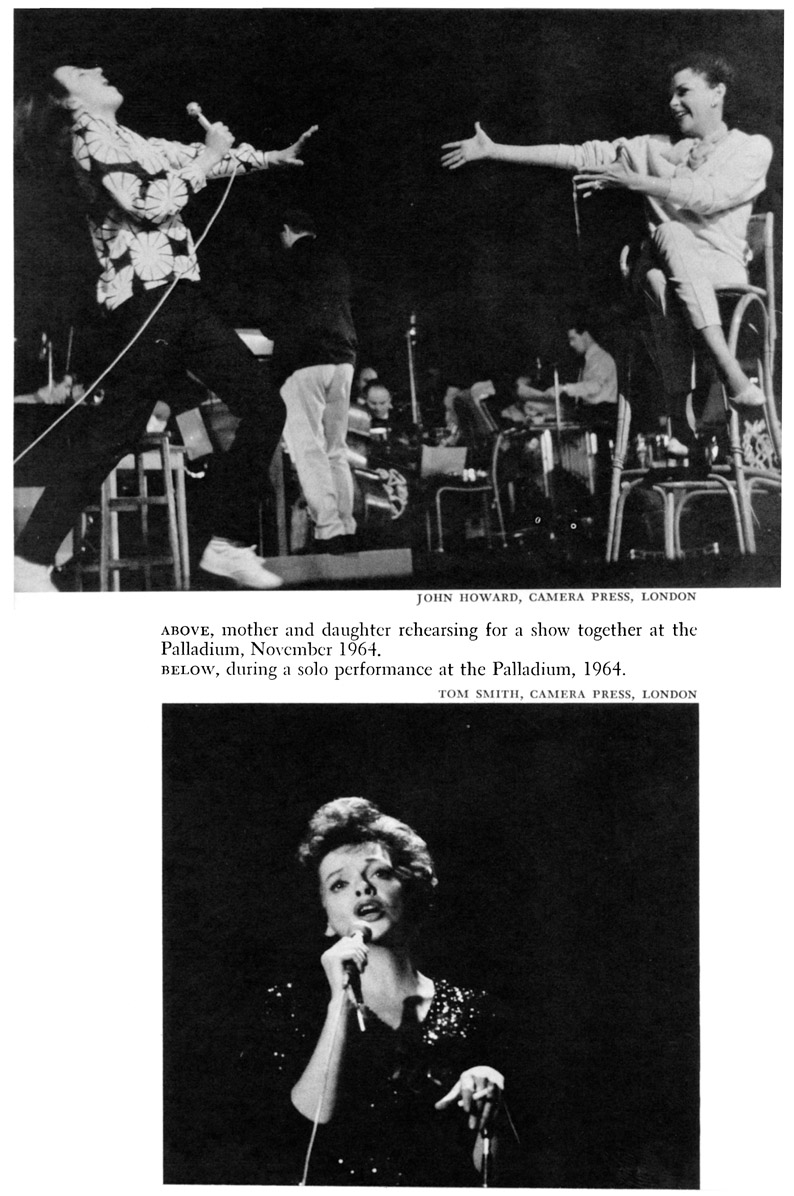

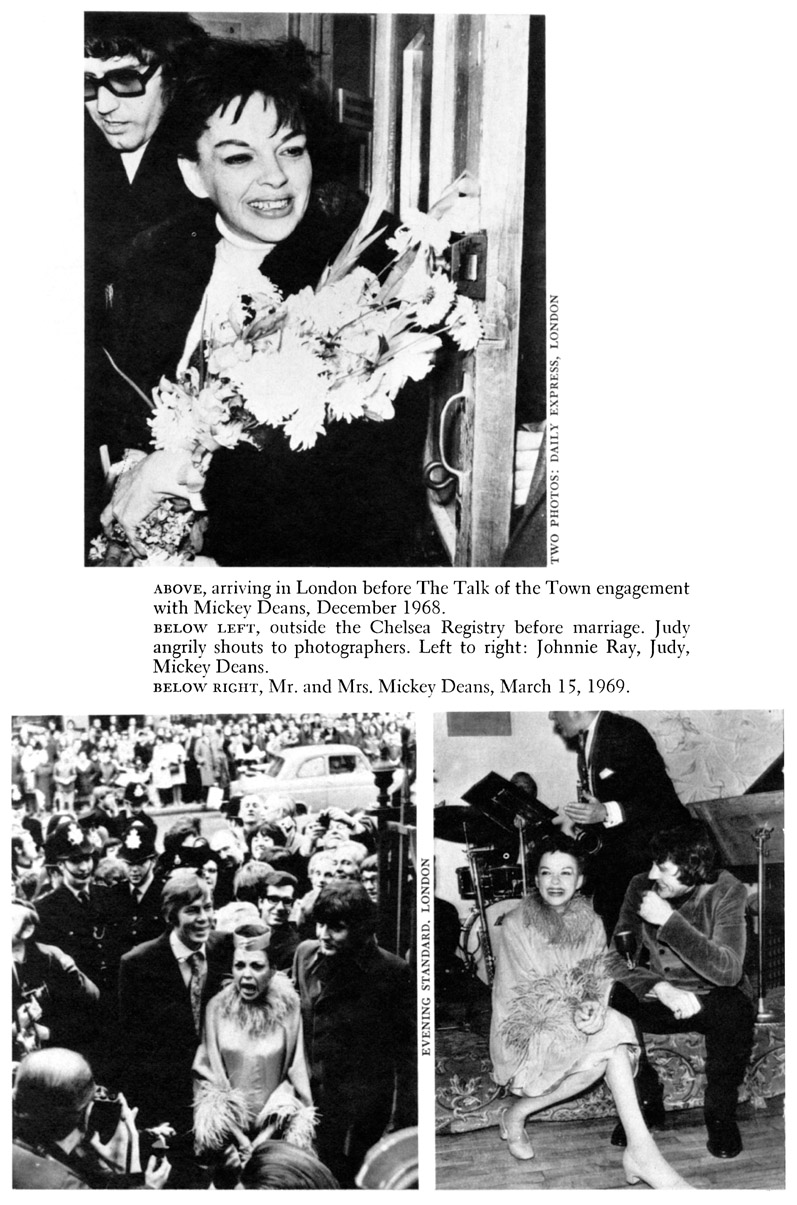

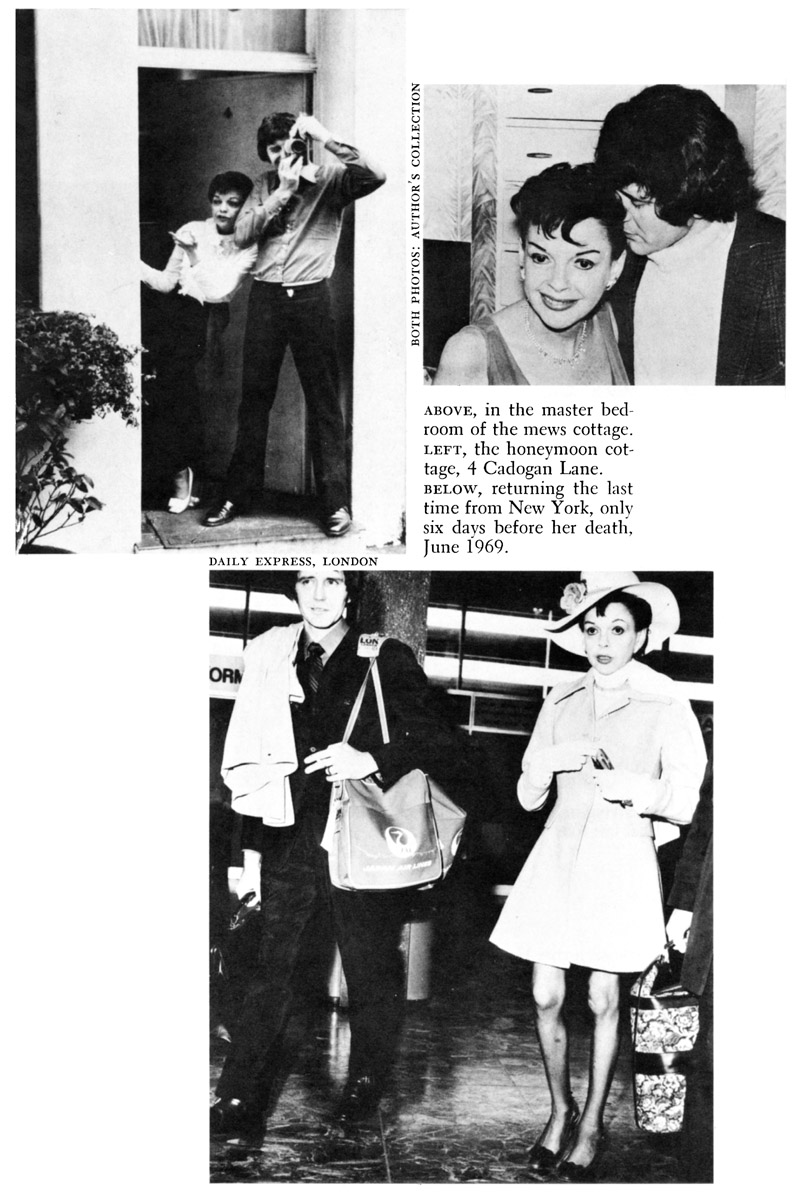

For the time being, however, Liza was to remain with her father. All arrangements had been made and the booking confirmed. Judy would open at the London Palladium on a Monday night, the ninth of April, 1951. Abe Lastfogel handled all the details. Once in London, the Foster Agency, representing William Morris (Lastfogel), was to take over. A very nervous and overweight Judy embarked for England on the lie de France with her secretary, Myrtle Tully, and Buddy Pepper, her accompanist. Pepper and Judy knew each other from childhood when they had both attended Mrs. Lawlor’s school. A product of vaudeville and a former friend of David Rose (who had been the one to encourage him to become a songwriter), he and Judy had much in common, though they had not seen each other for years; this eased the tension of the sailing.

Reporters boarded the ship at Plymouth and seemed shocked at the weight she had gained. (The next day, after reading their comments, Judy told Pepper, “From what I’ve read, I feel like the Fat Lady from Barnum and Bailey’s” and roared with laughter.) When Judy disembarked, crew and passengers remaining on board hung out of portholes to wave her goodbye; ships in the harbor flashed signals spelling out her name; and the lie de France gave a long, thunderous blast of its horn. Friends greeted her in London, and that was reassuring. Kay Thompson was appearing at the Cafe de Paris, and Danny Kaye had just ended an engagement at the Palladium, where he had been received with wild enthusiasm.

To look at her, it was hard to believe that less than six years had passed since the filming of The Clock, for in that short time her soft beauty had become harsh neon. She was twenty-eight and looked fifteen years older. She wasn’t plump. She was fat, weighing over one hundred fifty pounds—the fat devouring her tiny frame, distorting her features into a gargoyle caricature of herself. Her hair was sparse and dyed an ugly rubber-tire black. Dressed badly, but smiling winningly, she nonetheless captured the press. They loved her with a slavish devotion, and so, it seemed, did all of Great Britain. In spite of her feeling that she had been greeted with open arms, the night before the opening she was sleepless and terror-stricken. By daybreak she was pacing up and down her hotel room, still racked with fear. “I kept rushing to the bathroom to vomit,” Judy has said of that night. “I couldn’t eat; I couldn’t sleep; I couldn’t even sit down.”

When the Blitz was at its grittiest, when even the nightingales found it hard to sing in Berkeley Square, there had been Judy singing and dancing up the yellow brick road, giving English romantics a glimpse of happiness even in the darkest days of the war. A grateful nation would not forget this. Though it was springtime, 1951, there was still evidence of the war wherever you looked. Bombing sites waited reconstruction, their brick and mortar entrails still exposed. Charred and crumbling walls loomed darkly through the cold gray rain. Meat and sugar were still rationed. There was a shortage of cloth, paper, and string. Men tediously home-dry-cleaned their one worn suit; women made do with whatever they had.

Industry had virtually shut down for the war years and was slow now in beginning again. This meant that the entire country still had a look of the late thirties to it. Appliances were outdated by American standards—lighting and heating obsolete; cars and clothes were old-fashioned. The British film industry hadn’t yet regained its prewar status, and so American products and Hollywood stars came in for a great deal of idolatry.

The day of the concert, April 14, 1951, the press gave her encouragement and wished her well. It was the first time any press had been kind to her in years, and she drew some confidence from it. Some of the nervousness began to pass, but she still felt she might not be able to sustain herself without Sid.

After several overseas calls entreating him to join her, he hopped a plane, arriving only a few hours before her first appearance. He stayed close to her side, helping her fight her way into the theater through a cold, gray drizzle—hundreds of screaming, kerchiefed girls snatching at her, kissing her, shoving placards that read GOOD LUCK, JUDY in her face, and scrambling for autographs. When Sid finally got her to her dressing room, she was only half conscious. She kept repeating her fears and reminding everyone that she hadn’t worked at all in almost three years and had given a show in public only a few times since she had been a child.

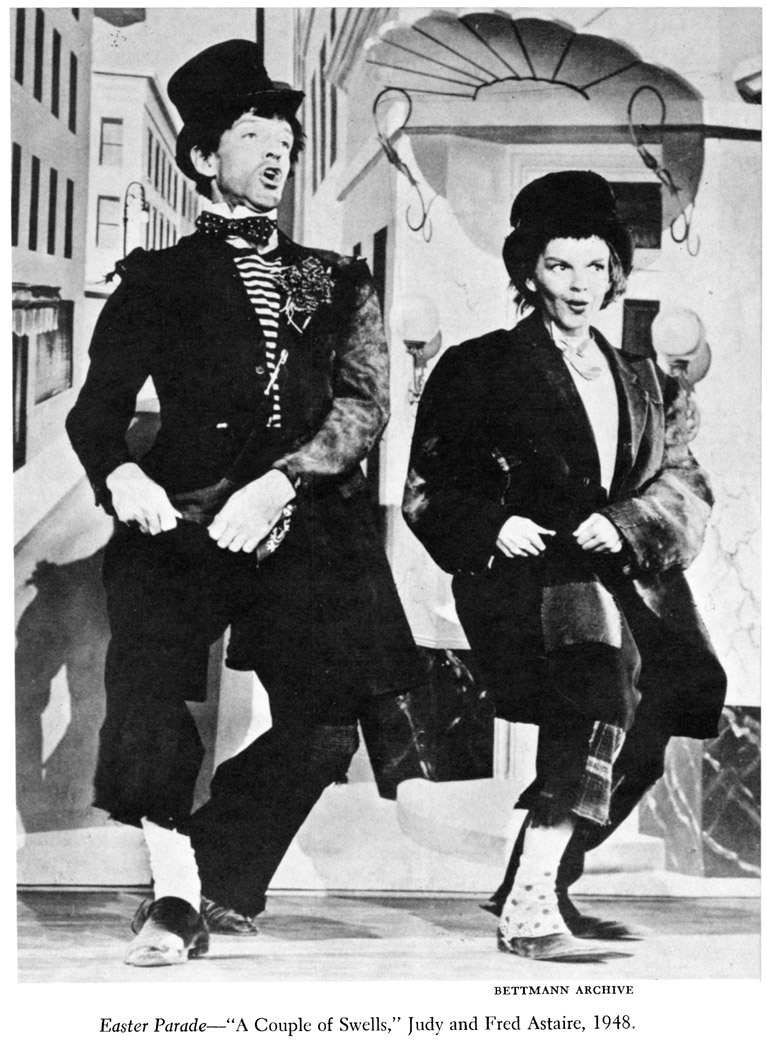

Talking to Joe Hyams (then of Photoplay magazine), she said of those last moments before she went onstage, “There were only minutes left. I had to get hold of myself. I said to myself, ‘What’s the matter, you dope? If you don’t cut this out, you won’t be able to sing’. . . . Standing in the wings, waiting to go on, I became paralyzed. My knees locked together and I walked on [stage] like a stiff-legged toy soldier.”

She should have had no professional doubts, for the only things off-key in her entire act were the two dresses she wore. The first, a flared lemon-yellow organza shot with glitter, made her look like a barrel of melting butter. It was still better than the black dress that followed. But that hardly seemed to matter —for when she finally stepped out of the shadows of the wings onto that huge stage, she was welcomed with a real Palladium roar that caused her to stumble. In a moment she had regained her footing. “Good old Judy!” yelled the audience. She blew them kisses; and when they had quieted, told them, “This is the greatest moment of my life.” Her voice trembled as she spoke, and her audience rose to their feet and cheered her.

One of the most striking features of her show was its thoroughgoing music hall quality. None of it was accidental. The early years were now paying off. All of Ethel’s training, Roger Edens’ coaching, Mickey Rooney’s goading were put to use. She approached the act in a typical variety manner, treating it as pure entertainment, never allowing herself to be overproduced, placing herself on an equal footing with her audience, consciously working to give everyone a good time, and firmly secure in the knowledge that audiences reacted to good lyrics. She gave each song a clear and lively interpretation.

After the first applause had subsided, she sang an introductory song telling how Danny Kaye had impressed upon her that she must play the Palladium. Then she went into a full-throated rendition of

It’s a long, long way to Piccadilly,

But at long last here I am!

Clutching the mike, she joked about her size.

“More to love!” her audience yelled back.

In her first number she was so overly anxious that the fury of her voice made the microphone tremble with her. She opened with “The Boy Next Door,” “Embraceable You,” and “Lime-house Blues.” Then she kicked off her shoes. “My feet hurt,” she confided. The audience laughed heartily. She thumped around the stage in her stocking feet and kept time to her singing with her big toe. She mopped her brow and wiped the tip of her nose with the back of her hand. “It’s not ladylike but extremely necessary,” she confessed. The audience was in the hollow of her hand.

It was to be a retrospective performance of all her past hits, and she began by being casual, discreetly hoydenish, her voice rich and vibrant—filling every nook and cranny of the gargantuan theater, expressing a new joyousness, a new aspect of herself. Toward the end, all lights but one went out. There was Judy in her stocking feet, sitting on the edge of the stage, the microphone so close to her lips that each tremor was echoed. The eyes were wide with wonder, scanning the darkness overhead, looking for bluebirds. There was an incredible transference. Judy sat trembling in adolescent wonder and hope and trust. She was the universal child of dreams.

In the moment of striking blackness that followed the last soaring note (Would she make it—would she? Yes! She did! Bravo! Cheers!) of the song, she replaced her shoes and, doing a small turn as the lights came on, as she began to exit, tripped over a microphone wire and fell flat and hard on her rear. Sid immediately shouted from his box seat out front, “You’re great, baby. You’re great!” And Kay Thompson, who was standing at the side of the stage, screamed, “Get back up! They love you!” The audience rose en masse as Buddy Pepper rushed to her and helped her to her feet. She was laughing nervously.

“That’s probably one of the most ungraceful exits ever made,” she said in that voice that often sounded as though it had tripped over microphone cords itself. Then she introduced Buddy Pepper.

The audience shouted back at her, “Good old Judy!” as they had before. She went offstage, but returned for an encore.

“Good night,” she finally yelled out over their whistles and screams. “Good night. I love you very much!” But she was brought out again—this time the stage looking like a conservatory, so filled with floral tributes was it.

The next morning the London Times reported: “Miss Judy Garland not only tops the bill at the Palladium this week, she also runs away with the show.”

All the Palladium reviews were raves. Not one faulted Judy’s performance, though they humorously criticized her costumes.

With the nightly excitement of her Palladium appearances, she was in very high spirits. After each performance her dressing room was mobbed and at least one celebrity would come backstage to congratulate her. She was up all night and slept most of the day. London was the Ritz Hotel or the theater or the Cafe de Paris.

When her engagement ended, four weeks later, a severe depression set in. It was a rainy May. London was gray and damp and shabby. For the first time she looked around her. There was a sense of the unreal, and she felt both longing and guilt at being separated from Liza for so long. Tension began between Sid and herself. She was, therefore, in the beginning, anxious and looking forward to the tour before them. Foster had set a tour of the provinces; but she decided to first go to Paris with Sid to buy some new dresses, and came back with two Balmain originals that, at least, were tasteful.

She opened at the Empire in Glasgow on May 21, at the Edinburgh Empire on May 29; spending June 10, her birthday, in Paris; returning the following night to open at the Palace in Manchester. A man in the audience called out for her to sing “Embrace Me.” “I’d love to,” she called back. She forgot lyrics to a song—and admitted it, and the audience encouraged her onward. When someone asked for “The Trolley Song,” she said, “I’m glad you asked for that one—we rehearsed it.”

On she went, the smell of train stations in her nostrils, the sound of thundering applause in her ears. The Empire in Liverpool, June 18; the Royal in Dublin, July 2; the Birmingham Hippodrome, July 9. In Birmingham she even made an 11:30 A.M. personal appearance at Lewis’ department store.

So closed her tour of Great Britain.

It took thirteen hours then to fly back across the Atlantic, but all that long distance Judy could recall to mind those last moments in Birmingham.

“Good night, good-bye, I love you very much,” she called out.

And to the last member of the audience, they stood and sang to her—"Auld Lang Syne.”

25In no fewer than twelve films she had played the wide-eyed, stagestruck girl who did or did not make the Palace. When she returned to New York after her triumph at the Palladium, that celluloid fantasy became her one real, main, and driving force. Walking through the streets of New York alone, as she was now able to do, she would end up always in front of the Palace, sensing more than irony in the fact that the Palace had become a cinema cathedral, and overcome with the injustice of that fact. Somehow, she told friends, the management must be persuaded to reinstate the two-a-day at the Palace—to bring back vaudeville.

No matter how triumphant her Palladium appearance had been, in her eyes she had not yet played the top until she played the Palace. She discussed it with Luft, and he went to Abe Lastfogel.

It was not difficult to understand the lure the Palace had for Judy. From 1913 to 1933, it had been the quintessence of the tops, the most refined in vaudeville, with the nation’s greatest entertainers performing twice a day, including Sunday. All the great stars of the past had played the Palace—Nora Bayes, Sophie Tucker, Fanny Brice, Eddie Cantor, Eva Tanguay, George Jessel, the Cohans and the Foys, Gallagher and Shean, the Dolly Sisters, “The Divine Sarah” Bernhardt, Ethel Barry-more, Lillian Russell, Will Rogers—all the top entertainers of the early twentieth century.

Then came the harsh times of the Depression. It was a losing scrimmage, but the Palace fought to keep vaudeville alive and the theater solvent by combining motion pictures and vaudeville acts. After three years vaudeville “died” more or less officially, and the Palace adopted a straight picture policy, which it maintained until 1949. In that year the theater again combined feature films with live entertainment; but it had lost the breathlessly young quality, the tingling excitement, the splendor and glory of vaudeville in its vigorous prime.

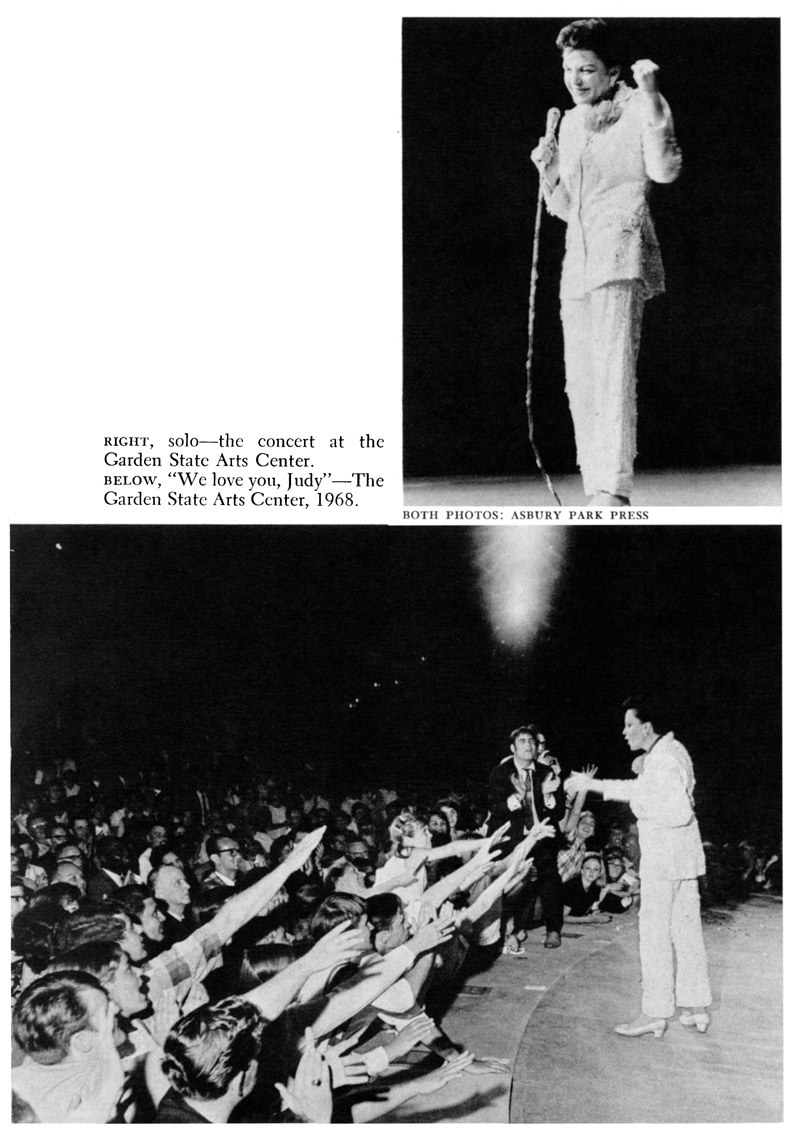

Judy’s success at the Palladium, the phenomenon of the mushrooming Garland Cult, her amazing versatility which enabled her to communicate quivering emotion and follow it with comic pratfalls, the driving vibrato that leaped, soared, swept across the footlights straight up to the second balcony of the great English music hall, encouraged the management of the Palace to go along with Luft and Lastfogel. The Palace could return to a live two-a-day routine, and Judy Garland was the only, the natural choice to launch the historic event. And so it was made public that on October 16, 1951, Judy Garland would open at the Palace, playing two shows a day, Sundays included.

Before her concert years Judy had always portrayed a wholesome, vulnerable, determined, and cheerful young woman, graciously childlike, always seeking to please, smiling bravely in the face of adversity. She was, of course, still that same woman, but now a new side of her personality had emerged. She no longer had to pose. She could do what she wanted: she was able to glut herself with food; say all the outrageous things she had always thought but not said; demand the love she had previously believed she might not deserve; sleep late; dress flashily; and live in an unmarried state with a man she loved. In effect, she was rejecting her past as all those in her past had once rejected her.

A wave of understanding swept across the nation’s rejects— the men and women who had never been accepted as they were. Judy’s incredible rebirth; the unleashing of her true spirit; her defiance of convention; and most of all, the true beauty of her soul that soared from her in song, the honest pain and anguish she exposed when singing, caused them to rise up and at any cost to reach her, to let her know she was not alone, that they would protect her, that they understood, that they accepted her for herself and perceived her need for both a dialogue and an outstretched hand.

This was Judy’s new audience. They were to be not only in the palm of her hand, but also staunchly in her corner. As soon as the announcement hit the papers that she was to reopen the two-a-day at the Palace, they hitched, walked, bused until they reached New York; and once there, they let Judy know of their presence. This army of protectors was a new experience to her. There was no question that she immediately encouraged their devotion.

It was October in New York—a brisk, beautiful autumn. Vivien Leigh was the talk of the film world with her screen performance of Blanche Dubois in A Streetcar Named Desire; Gertrude Lawrence was thrilling audiences on Broadway opposite newcomer Yul Brynner in The King and I. Katharine Hepburn had returned to the theater to do Shakespeare in a brilliant production of As You Like It; and at Madison Square Garden, Marlene Dietrich startled a circus audience by appearing as ringmaster, dressed in a brief costume of her own design—black tights, top hat, and a scarlet cutaway jacket. She stood in the dark immensity of the ring, took the microphone, and said to the entranced audience in her inimitable deep, warm, cavernous voice, “He-looo, are you having any fun?”

Harry Truman was in the White House, with Alben Barkley as Vice President. North Korea had invaded South Korea, and the United States had sent in troops. Joseph McCarthy and the Senate Investigating Committee filled the press and the television screens as the “Hollywood Ten” went “on trial” before an unconstitutional committee of which a young man named Richard Nixon was a prosecuting attorney. Jacqueline Bouvier had not yet met John Kennedy, but she had just written the winning essay for Vogue’s Prix de Paris stating that the three men she would’ve liked to have known were Charles Baudelaire, Oscar Wilde, and Sergei Diaghilev.

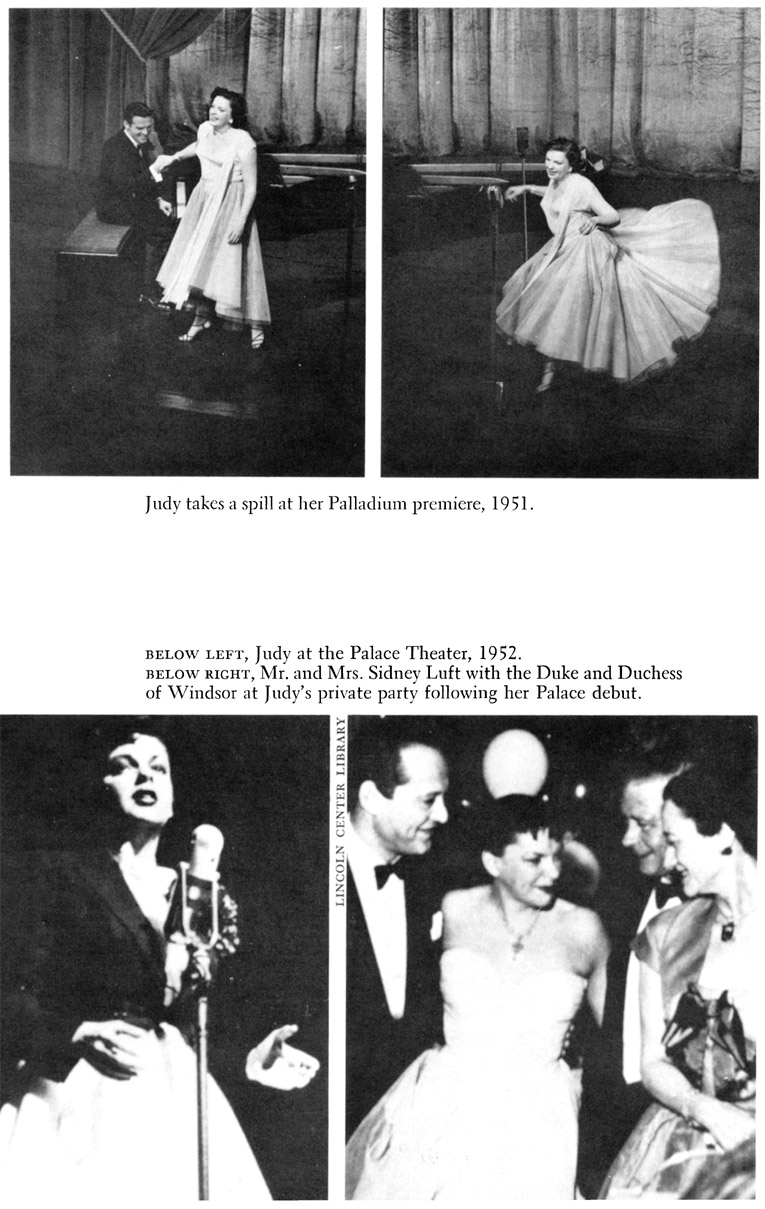

Ladies’ skirts were at an all-time ugly length—mid-calf; but this time Judy’s gowns were designed for her by Irene Sharaff, the well-known MGM designer, and good taste and good sense established a style for the performance that had not existed in her appearance at the Palladium. In fact, there was the ambience of a Metro extravaganza about the entire production.

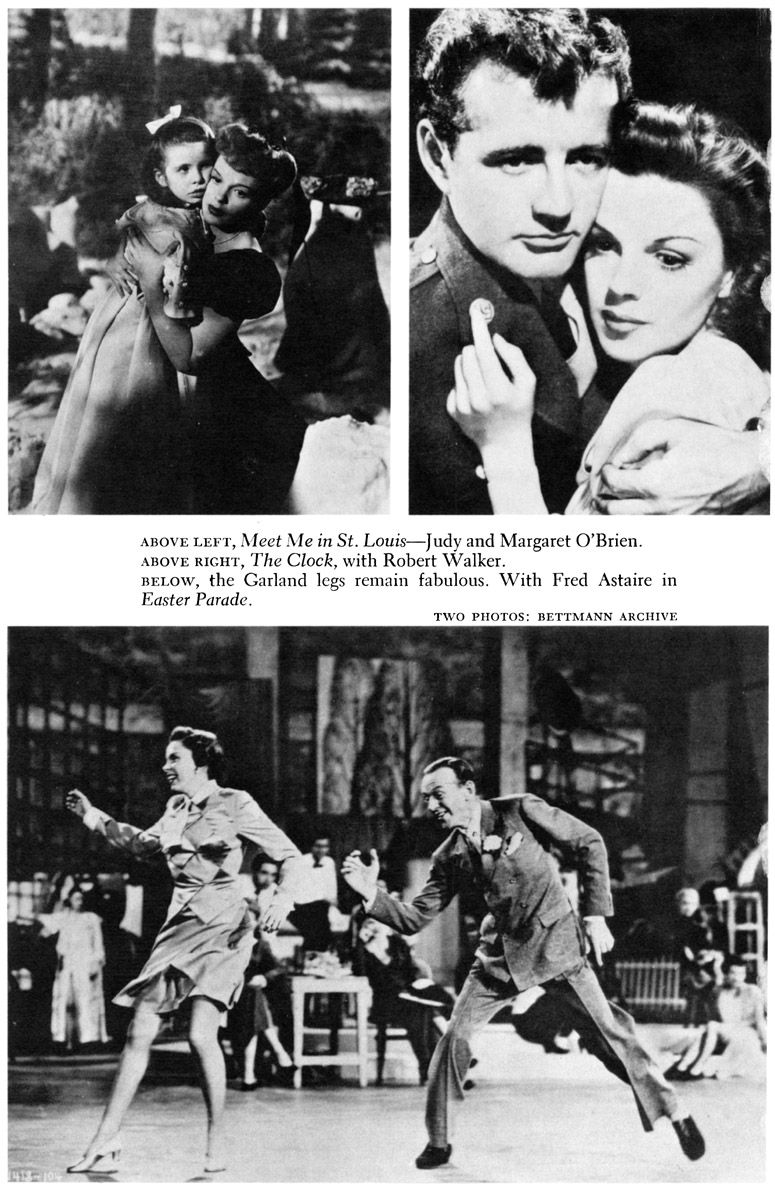

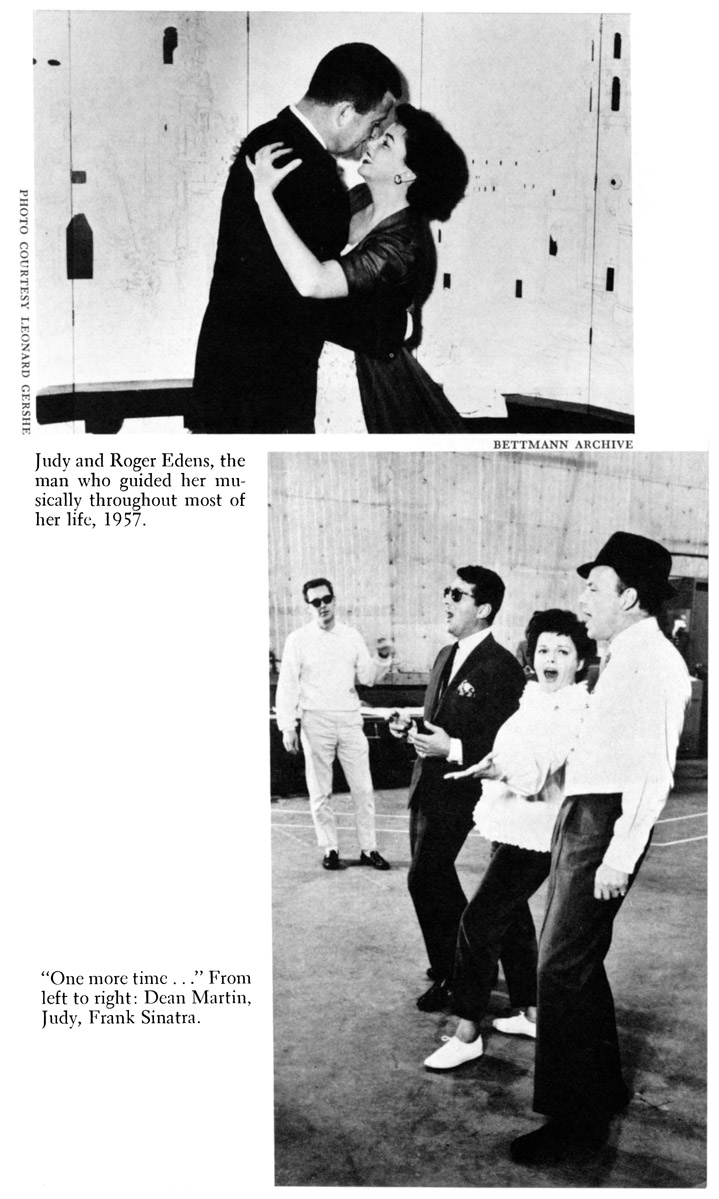

Under Luft’s supervision the Palace had been completely renovated, the decor having an essence of Hollywood grandeur and a heavy-handed Hollywood touch. Judy’s act was staged and directed by that old bullwhipper himself, Charles Walters; Roger Edens did all the special lyrics and musical arrangements; and Hugh Martin, who had written the score of Meet Me in St. Louis and given her the great hit “The Trolley Song,” accompanied her. All of these artists were mentioned in the program as “appearing through the courtesy of MGM Studios.” One might, with a sense of irony, say Judy was as well!

Priceless paintings were borrowed from the extensive collection of E. F. Albee and exhibited in the lobby; flashing crystal chandeliers replaced the outdated lighting; walls were painted a creamy ivory and trimmed in glistening gold; and a red velvet carpet was spread from the curb in front of the theater right up to the stage.

Opening night, a solid police cordon was called out to keep in check the mass of fans that teemed Duffy Square. Tickets were a $6 top, and the house was sold out, with signs reading NO STANDING ROOM. Backstage, Judy, pacing nervously amid the huge bouquets in her dressing room and flanked by Luft and accompanist Hugh Martin, was filled with the same last-minute opening-night terror she had experienced at the Palladium.

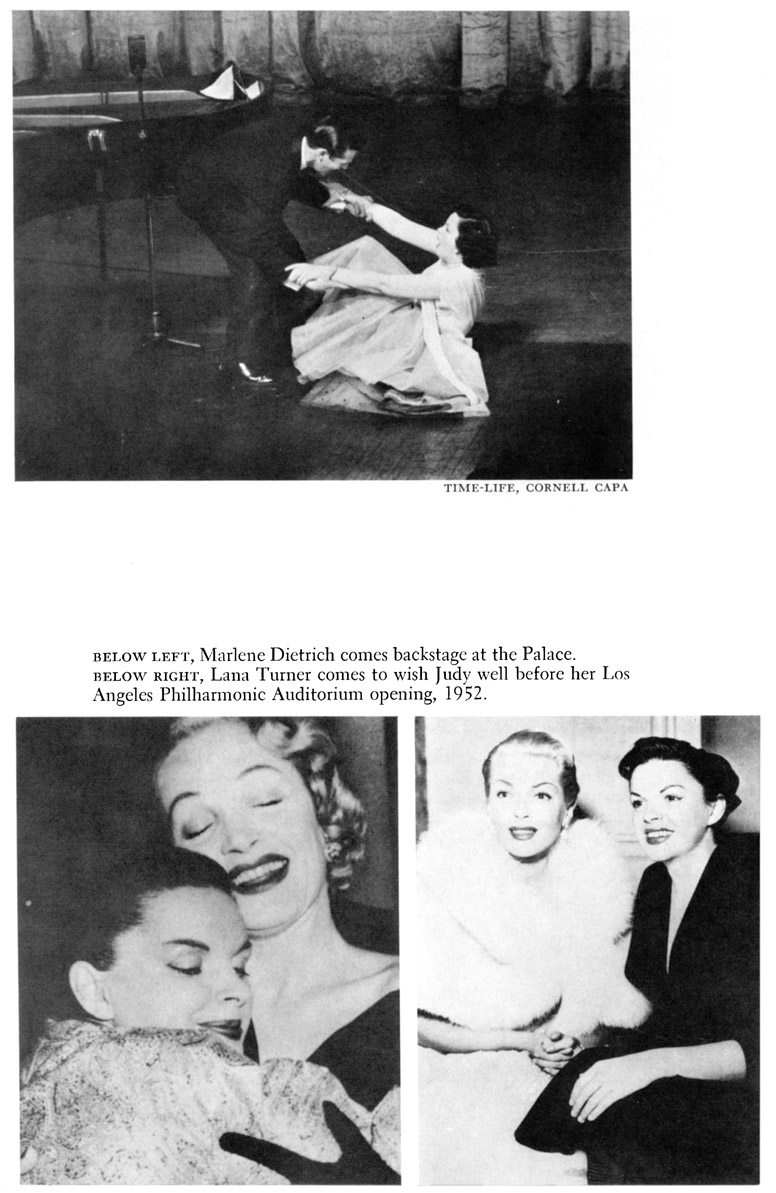

She was dressed in stylish black; but she was aware that while slimmer than she had been in England, she was still grossly overweight, and that an audience blazing with jewels worn by society figures and film stars—an audience of famous people like the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, Marlene Dietrich, Gloria Swanson, Durante (who had once played the Palace himself), and Jack Benny—now being shown to their seats, had never seen her fat.

She was scheduled to appear in the second half of the program, directly following the intermission—the usual spot for the top act in a vaudeville revue. After an overture led by orchestra conductor Don Albert, which included a medley of Garland hits, a teeterboard group opened the show. They were followed by the youthful Doodles and Spider, who were making their first Broadway appearance—though they had previously scored heavily at The Blue Angel. Then came Smith and Dale, the grand old vaudeville team who had, in 1909, headlined the first Ail-American vaudeville bill in Europe. Continental dancing stars Giselle and Francois Szony, a brother-and-sister act, appeared next. Comedian Max Bygraves, who had appeared with Judy at the Palladium, closed the first half.

As the plush and elegant red velvet curtains opened after the intermission, Don Albert raised his baton, and a group of eight young men billed as Judy’s Eight Boy Friends danced out onstage and introduced her. Judy stood, keyed up in the wings, snapping her fingers, tapping her foot to the beat of the music. Stepping from the wings on cue, she remained initially concealed by her chorus line of youthful male hoofers. There was a flash of her black velvet gown as they parted to let her through. On her appearance the audience stood and shouted, applauding wildly. Judy stepped to the footlights. The applause grew. She cupped her hands and yelled, “Hello!” at the top of her voice. The audience laughed, and Judy with them. Judy was more at ease and in command than she had been at the Palladium. She felt a rapport with the audience; and as Don Albert led the orchestra into her opening number—“Until You Play the Palace”—they quieted and sat down while Judy remained at the footlights for the opening bars. It was a warm and welcoming gesture.

The “Palace” number was reminiscent of the Palladium opener—“It’s a Long Way to Piccadilly”—in that Judy was having a musical dialogue with her audience. She related a few facts about her career, kidded the newspapermen about probably reporting that she needed to lose another ninety pounds, and then paid homage to the Palace and the great stars who had preceded her, singing their greatest hits—Fanny Brice’s “My Man,” Sophie Tucker’s “Some of These Days,” and Eva Tanguay’s “I Don’t Care.”

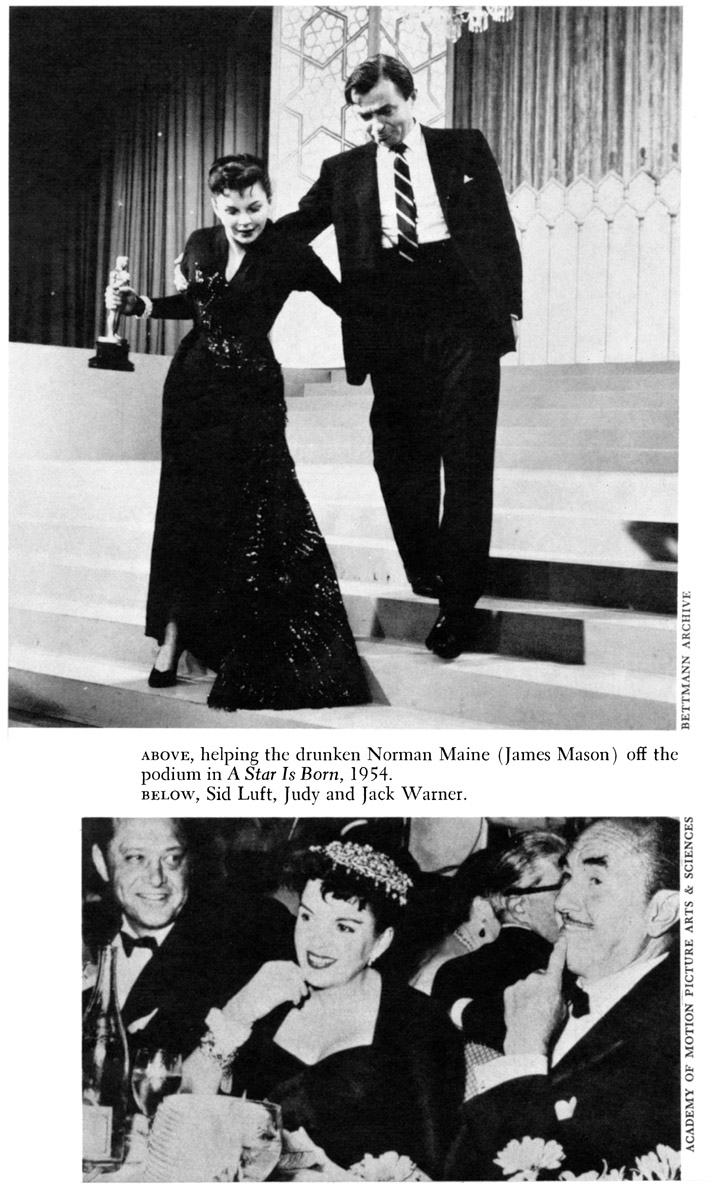

By now the audience was cheering her on to do her own songs. She was beginning to feel the power, the chemistry, the connection between the audience and herself. Tossing the microphone wire over her shoulder in a gesture that was pure camp (she had used a similar gesture at the Palladium but with not so much bravado), she set the mood for the performance to follow. Striding back and forth across the stage, she welcomed Hugh Martin and then launched into “You Made Me Love You,” after which she belted out “Rock-a-Bye Your Baby,” “The Trolley Song,” “For Me and My Gal,” and “Come Rain or Come Shine.” She picked up her skirt to reveal an orange crinoline petticoat and wiped her brow with a matching orange handkerchief. “Gotta have some water,” she exclaimed. “You don’t know how hot it is up here.” Then, taking a pitcher and a glass off the top of Hugh Martin’s piano, she walked to the footlights with it. “Anybody want a glass of water?” she asked in a clear, ringing voice. She used a lot of the same dialogue she had introduced into her English performances, but made it sound completely spontaneous. Returning to the piano, she did some dance steps, this time without falling, and on an almost blacked-out stage managed a few smooth and humorous pratfalls with Charles Walters.

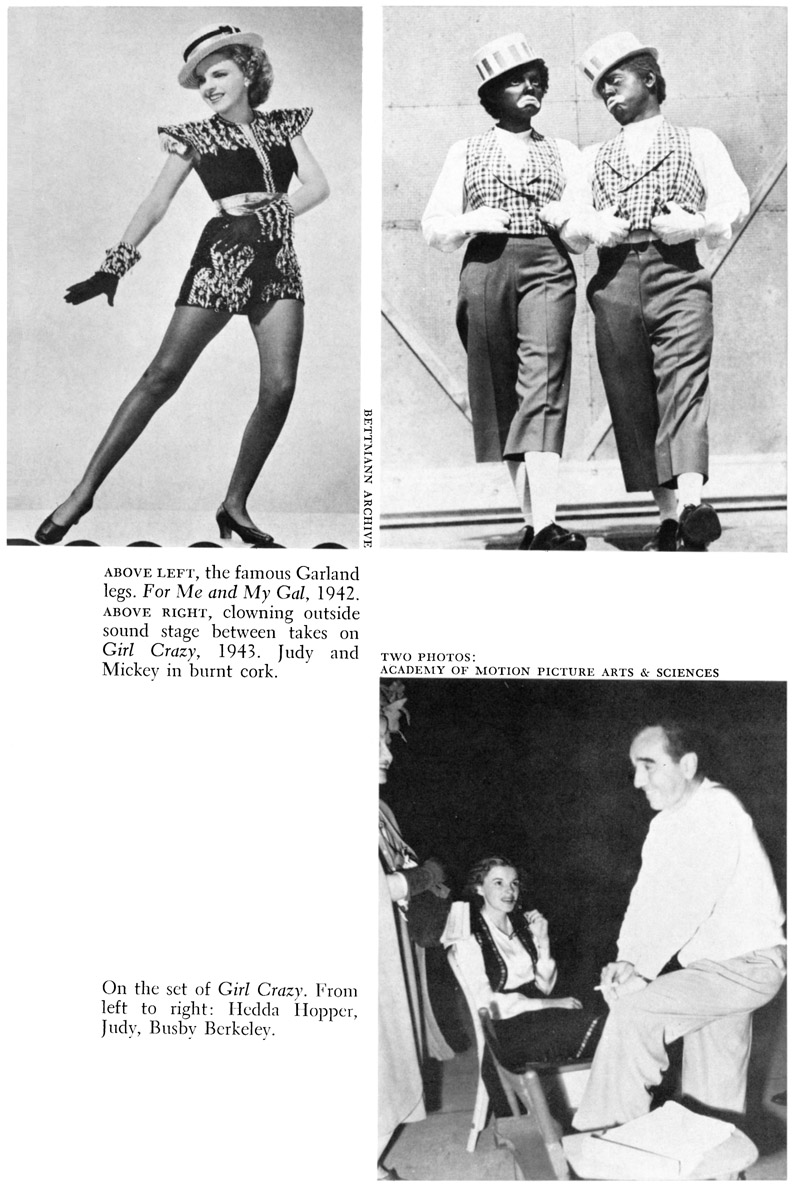

Leaving the Eight Boy Friends to do a number on their own, she startled the audience on her return to the footlights by having stripped down to black tights, a dashing tuxedo top, and a top hat to sing “Hallelujah, Come On, Get Happy!” from Summer Stock. It was perhaps the most theatrical moment in the show, for despite her weight the Garland legs were still exquisite and difficult to tear one’s eyes from. The house rose to a tumultuous ovation at the end of this number, and the continuing applause covered the opening bars of “This Is My Lucky Day.”

While Judy’s Eight Boy Friends once again held the stage, she changed costumes, reappearing this time in chalky tramp makeup and baggy hobo costume and assisted by an agile male partner, Jack McClendon, did the “We’re a Couple of Swells” number from Easter Parade. The true gamin in her shone forth. She grinned mischievously through blacked-out teeth, fluttered her battered hat, and batted her painted eyes. The audience screamed out their approval; and she stood there—the lonely tramp: the Chaplin pose Ethel had taught her so many years before—and waited. It was a long time before silence came. When it did, she went down to the footlights, battered hat in hand, sitting down in the footlight trough. Only one light on her face remained; the rest of the stage was in blackness. Cupping her chin in her hands and with tears in her eyes, she sang “Somewhere Over The Rainbow.”

The theater had never seemed more alive than it did with Judy poised on the edge of the stage in that cavernous darkness voicing a lost child’s pitiful lament; and there wasn’t a dry eye in the house when she was done. She stood, and for a full three minutes the audience cheered and applauded her. “I’m not good at making speeches,” she finally faltered. “What can I say except bless you, good night, and I love you very much.”

At that point the usherettes came down the aisles and filled the stage with floral tributes, and it was many minutes more before the audience would let her leave.

Once again, as in London (though now polished and used to best advantage), her performance carried little admixtures of “salesmanship”—perhaps Walters and Lastfogel and Luft might have called it “showmanship.” In many ways this tainted the essential purity of her performance, but it did infuse her with a new image. There was a certain frenzy in her attitude— the quick staccato steps alternating with impatient striding across the stage, the whiplike tossing of the microphone cord over her shoulder, grabbing the instrument itself in an almost desperate manner, the impassioned energy in the delivery of her songs.

There was no question that in an effort to fit up-to-date American entertainment values she had permitted herself to be “presented”—that is, slightly industrialized. The act was flashy, and some thought it succeeded in spite of this, not because of it.

Quoting Harold Clurman:

[Judy] is at bottom a sort of early twentieth-century country kid, but the marks of the big city wounds of our day are upon her. Her poetry is not only in the things she has survived, but in a violent need to pour them forth in vivid popular form, which makes her the very epitome of the theatrical personality. The tension between the unctuously bright slickness which is expected of her medium and environment and the fierceness of what her being wants to cry out produces something positively orgastic in the final effect.

This was a historic night for her. She now knew that she had opened a new and exciting door in her career; there was the admiration of her peers, the adulation of her fans, a basket of roses sent by Minnelli in Liza’s name to make her feel her child was with her; and there was Sid Luft, glowing, cheering, loving. There had been a call from Ethel, and its effect remained the only tinge of uneasiness she had. Instinctively she knew Sid and Ethel would someday cross swords, and she was honest enough with herself to know who must win and to feel the first pangs of a guilt toward Ethel that would never again desert her.

Backstage was pandemonium. Mobs of reporters, photographers, and well-wishers crowded around her, all telling her how wonderful she was. “Thank you, thank you,” she repeated again and again, grasping, holding on to each extended hand. “Are you coming to my party?” she would inquire. “You must come to my party. I’ll probably go straight home and collapse, but you must go to my party!” Everyone laughed.

Luft had planned a reception for her at the “21” Club. She changed into an ultrafeminine blue tulle off-the-shoulder. The confusion had already set in. She was the toast of Broadway, but she was dressed like a Hollywood starlet at a studio preview.

At least five thousand fans blocked her exit. “I’ve been on this beat twenty years,” a policeman said. “I’m telling you I’ve never seen anything like it.” Sid and four policemen guided her through the crowd. All around her rose shouts of “Judy! Bravo! Bravo!” To Judy they must have drowned out even the harsh sounds of nighttime Manhattan.

The sophisticated and crowded interior of the “21” Club looked a bit like a Metro spectacular. It seemed everyone was there and toasting Judy in the most expensive champagne. Luft was ostensibly the host, but in fact, Judy was picking up the tab. It did not diminish her excitement as she waited with all her supporters for the morning newspapers to carry the reviews.

But what a grand irony that Robert Garland, the man whose name she had borrowed and then kept as her own twenty years before, was the man chosen by the Journal-American to review the show! “There were shining show people in the good old days,” he wrote. “There can be shining show people now. Witness Miss Garland. It is as if vaudeville had been waiting somewhere for her to come along, and she, in turn, for vaudeville.”

But perhaps the most moving review was written by Clifton Fadiman and appeared in Holiday magazine several months later. “As with all true clowns,” wrote Mr. Fadiman,

. . . she seemed to be neither male nor female, young nor old, pretty nor plain. She had no “glamour,” only magic. She was gaiety itself, yearning itself, fun itself.

. . . She wasn’t being judged or enjoyed, not even watched or heard. She was only being felt, as one feels the quiet run of one’s own blood, the shiver of the spine, Housman’s prickle of the skin; and when looking about eighteen inches high sitting hunched over the stage with only a tiny spotlight pinpointing her elf face, she breathed the last phrases of “Over the Rainbow” and cried out its universal, unanswerable query, “Why can’t I?,” it was as though the bewildered hearts of all the people in the world had moved quietly together and become one, shaking in Judy’s throat, and there breaking.

For nineteen weeks she played to packed houses. The grind was brutal. On a Sunday less than four weeks after she had opened she collapsed and was rushed to the Le Roy Hospital on Sixty-first Street, and there treated by a Dr. Udall Salamon for nervous exhaustion. By midweek she was back onstage. It was a marathon engagement. Eight hundred thousand people came to see her—breaking every existing record at the Palace.

She closed on a Sunday, February 24, 1952. Jimmy Stewart and Lauritz Melchior, the Metropolitan Opera star, were in the audience. Both joined her onstage at the finale, and Mr. Melchior, who was to follow her into the Palace, led the audience in a music tribute, singing—as her last English audience had sung—"Auld Lang Syne.”

The past would appear over and done with—swept away, lost, forgotten in the vitality of her new self, her newfound life-style. Luft was by her side. They were living a brassy, late-night life, thriving on nightclub smoke, surrounded by new faces—Broadway folk, nightclub habitués, musicians, and gamblers. She had earned $20,000 a week at the Palace and had never seen a penny of it, trusting Luft and Lastfogel to handle the finances. The Garland bandwagon had greased its motor and refueled, and the world was once again climbing aboard. But Judy loved the feeling of being “surrounded.” She was, in fact, very happy. Liza was on her mind, but she dreamed of a new future for the child, and she was looking forward to their being reunited.

She was, in fact, heading toward California. For on April 26, she was to open at the Philharmonic Auditorium in Los Angeles.

Hollywood columnists Sheilah Graham, Hedda Hopper, and Mayer’s old friend Louella Parsons all announced from their Hollywood perches that Judy was on “thecomeback road”

26In an interview before her Los Angeles opening Judy told the world, “Sid has done it for me; that’s my fella.” And Luft had added: “I love Judy. I want to protect her from the trauma she once knew. I don’t want her to be bewildered or hurt again. I want her to have happiness.”

Judy was desperately in love and experiencing new sensations. There was a certain abandon in her feelings toward Luft that she had never felt before. Sid was tough, strong, and opinionated. From the onset of their relationship he was Number One and Judy the follower. She loved the role. It made her feel extremely feminine. She told herself she would be protected now, cared for, understood. But at heart she remained dreadfully insecure. Accordingly, she found herself constantly testing him. Therefore, there was never truly a time when they didn’t have “spats.”

While still with Luft, she wrote an article for Coronet magazine titled “How Not to Love A Woman,” in which she stated, “We [women] must know, beyond doubt, that we’re safe with you [men]. That you can take it, that you are not bluffing about your strength and most of all, that you care enough to win.” And in another part of the article she writes, “We will seem to be fighting you to the last ditch for final authority . . . But in the obscure recesses of our hearts, we want you to win. You have to win. For we aren’t really made for leadership. It’s a pose.”

Luft was not about to yield his leadership or hand Judy the reins, as she might have feared. Yes, there were moments of confusion, twinges of alarm, an instinct that perhaps she should pull back. Always moved by the passage in the Bible in the Book of Ruth, “Whither thou goest, I will go, and where thou lodgest, I will lodge,” she comments at the end of her Coronet article on this philosophy: “We weep because we think of it as a beautiful description of woman the follower. To many of us it means that you [men] alone must be the leader. If you are, nothing else really matters.”

There was, however, that key word “leader”—its interpretation and the confusion it brought to Judy. Luft had a strength that was born of toughness, not courage, and an ability not so much to lead as to drive others who could help him satisfy his own needs. In Judy’s case and at this point in her life, the latter worked as a positive force. Luft craved the limelight, a showy, ostentatious life—wanted to be “in the big time.” He had already come to terms with his own inability to gain these ends by himself. All of which gave his one true talent—the art of promoting—a thrust forward.

Luft was, however, no Mike Todd or P. T. Barnum. Lacking their genius, he had to first have a presold product. Where he could not succeed in making Lynn Bari a star of the first magnitude, he could take a star—Judy—and keep her in orbit. There were perhaps other agents, managers, promoters (who would have come into no more than 10 percent of the take) who could have done the same thing. But no one was willing to take the time, give the dedication, and risk the chance of personal jeopardy that working with Judy imposed. This was Luft’s additive—the extra ingredient that enabled him to get Judy on her feet, bigger, better, and more of a money-maker than ever before. In effect, he took over her life on a twenty-four-hour-a-day basis. He bullied her, pushed her, praised her, beat her down, picked her up—at each turn carefully weighing which would in the end get her up on that stage playing to packed houses.

Until the very end of her affiliation with Luft, Judy claimed she never saw any of the money she made and in the early years never inquired about its disposition. Her feeling that Luft had to be Number One was a good assessment of his personality. By the time they were headed for California, he exerted full control over her. His ability to do this was one of his greatest attractions for Judy and certainly a complete reversal of the passivity of David Rose and the aestheticism of Vincente Minnelli. Only Mayer—and before him, Ethel—had ever made her sense that another power was greater than her own. Mayer was ostensibly out of her life, but Ethel was waiting for her in Los Angeles. Judy had not seen her in a year, and Luft and Ethel had not yet met. That meeting was scheduled shortly after their arrival in California. Depending on whose viewpoint one subscribed to, it was both fatal and highly successful. Each took an instant dislike to the other, and Ethel was made to understand that she was now the complete and total outsider.

Ethel was bereft. She was also aware that she stood no chance of cracking through the wall Luft placed between Judy and herself, because he would be on constant guard. She was extremely disturbed. She developed a painful ulcer, and her own resources were now shrunken so that her standard of living had to be altered. She had become fearful of her financial future—having always relied on Judy’s support, she feared Luft might influence Judy to withdraw it; but she was also concerned that he might exert other influences on Judy and that she might be losing her place in her daughter’s life.

Sought out by the press, Ethel made some unflattering remarks about Luft, ambiguously saying she thought he was bad for Judy but not specifying how or why. As soon as the newspaper report appeared, she had second thoughts on what she had done and tried to contact Judy, but to no avail—being told her daughter could not be reached. Asking the stranger to whom she was speaking (who was someone obviously in Judy’s employ) if Judy was disturbed by the newspaper report, Ethel received the reply that she was not. But, of course, this did not represent the truth. Judy was bitterly hurt and very protective of Luft. She refused to see Ethel while she was in Los Angeles. Fate stepped in and decreed that they were not to see each other again, though their tremendous mutual ability to create deep-rooted disturbances in the other’s life was far from over. Luft could pressure Judy not to see Ethel, but later it was beyond his capacity to exorcise Ethel’s ghost from her daughter’s psyche.

Judy could not have perceived it at the time, but her record run at the Palace had already made her a legend. The resurgent star now found herself with a frenzied following. Scalpers were getting $100 a pair for tickets to the opening at the Los Angeles Philharmonic Auditorium, and all seats were sold out to the premiere performance weeks before April 26, the scheduled date. Opening night was a replay of the Palace opening—wild applause and shouts of Bravo! rang through the huge old hall— and the engagement was sold out for the entirety of its four-week run.

There was nothing Hollywood despised more than failure, and nothing it venerated more than popular success. Having grown up in this selfsame society, Judy was geared to its values. Each day she rose with the terrible anxiety that that night the show would fail and Hollywood shake its success-oriented head. “Well, we were right,” she was afraid people would say. She also began to question the meaning of her concert success, for Hollywood people were fairly contemptuous of any medium through which only scant thousands could be reached. Their power remained in packaging for millions; and among themselves they cast doubts that Judy, looking fat and matronly, would have succeeded without the power of film magnetism that they had invested in her. The whispers were not kept in private corridors, and so their innuendos came back to whistle like a stubborn wind beneath her dressing-room door.

Even Luft’s encouragement and Liza’s proximity could not ease the rumblings of anxiety that she was beginning to experience. No sooner had she arrived in Hollywood than she began to push to leave it. Luft was working on a San Francisco appearance to follow, and that gave her something concrete to look to.

Her record Judy at the Palace (Copyright 1951, Decca Records, Inc.) had just been released and was selling extremely well, and she had signed a five-year contract with RCA Victor Records. There was no reason for her to feel insecure—but nonetheless, she did. Her final decree of divorce came through before she completed her Los Angeles appearance. She was a free woman. To Judy that meant only that she was now free to marry the man she loved.

On June 11, 1952, Judy took one day away from her San Francisco concert appearance at the Curran Theatre and she and Luft were married in a simple, five-minute ceremony at the Hollister, California, ranch of a wealthy friend. That night Judy was back performing at the Curran. It was a preview of what their married life was to be like.

Only hours after the ceremony Luft was sued by Lynn Bari, claiming that Judy had earned $750,000 in 1951 and that Luft, as her manager, had received a large portion of it. Miss Bari asked the court to raise Luft’s $200 monthly support payments to their son to $500. Judge Burke in Superior Court in Hollywood ordered that the amount of $400 monthly be paid over.

Their court problems did not end there. Ethel—angry, pressed by her own fears and financial needs—now went to court to claim nonsupport from her “high-salaried” daughter. Judy was profoundly disturbed and confused. In the end, incensed that Ethel would trot their differences out into public and into court, she stood her ground, declaring that her mother was a capable piano and singing teacher, having instructed her, and was qualified to run a movie theater as well. She then had records produced to show what moneys had been paid to Ethel in the past. Ethel’s case fell through. A greater estrangement was created between mother and daughter.

It did not help that on July 19, Ethel “bared her soul” to columnist Sheilah Graham in a coast-to-coast interview. “Judy has been selfish all her life,” she declared. “That’s my fault. I made it too easy for her. She worked, but that’s all she ever wanted, to be an actress. She never said, ‘I want to be kind or loved,’ only ‘I want to be famous.’ ” She added that she wanted nothing further from Judy and that she wished the press would forget her as Judy most obviously had done.

Ethel then took a $60-a-week job at Douglas Aircraft, working on the assembly line, and immediately confided this news to a few of her friends who happened to be members of the press.

Judy was pregnant and had been since her San Francisco concert. In the advanced stages of the pregnancy she took very sick. She was swollen with edema and dangerously overweight. Luft was seldom at home, his twenty-four-hour-a-day supervision ending with her inability to appear onstage. The honeymoon was over. Judy has said, “From the beginning Sid and I weren’t happy. I don’t know why. I really don’t. For me it was work, work, work; and then I didn’t see much of Sid. He was always dashing off to places lining up my appearances. I wasn’t made any happier looking into mirrors seeing myself balloon out of shape from liquids trapped in my body.”

The doctors claimed her condition was caused by a metabolic imbalance and that the weight was, indeed, liquid trapped in her body. New fears set in: she would lose Sid; she would lose the baby; her concert career was over—having been only a flash in her life; she would die in delivery. (There was still the painful and frightening remembrance of Liza’s birth.)

On December 8, 1952, she gave birth to a little girl. They named her Lorna. The child was healthy and beautiful, and Judy seemed to feel renewed and happy. It was to be the one bright and happy spot in her life for quite a while; for on January 5, 1953, less than four weeks later, Ethel fell dead in the parking lot of Douglas Aircraft of a heart seizure that had occurred at seven-thirty in the morning. She was discovered between two parked cars on her hands and knees, as though desperately trying to crawl for help.

Judy collapsed. It was not one of those convenient “collapses” famous stars have in order to avoid the press. She was not hiding under a bed so that she did not have to answer questions—though to be sure, the whole sordid, unsavory story of Judy’s “abandonment” of Ethel in these last days of dire circumstances was rehashed, in the press. Forgotten was the Judge’s just decree after studying all the evidence: that Judy not pay Ethel support. It made a far more dramatic story for the press to ignore that.

The irony, of course, was that Judy had been supporting her mother since she had been a very small child. All their lives their roles had been reversed in that respect. And had Ethel been cautious with the money Judy gave her, neither of them need ever have had financial insecurities. The further irony was that only in the last six months of Ethel’s life had Judy withdrawn monthly support, having maintained Ethel at times when she herself was deeply in debt. Actually, Ethel had more security than Judy, having received cash for a theater she and Gilmore had owned in Dallas and having a small income from investments made with Judy’s early earnings.

It is hard to understand why, if Ethel felt she must work, she chose a factory assembly-line job when there were many more lucrative jobs open to her. She could certainly have secured a position in publicity, costuming (she was still an expert seamstress), theater management, booking, or, as previously mentioned, as a piano teacher or coach. She also had a large family whom she, through Judy’s bounty, had been very good to all the years of Judy’s career and whom she certainly could have called on had she truly been in need.

The court suit for support, then, appears to have been a vituperative action initiated in anger and meant to censure or embarrass Judy on one hand and on the other, threaten Judy— as the old hotel-room-desertion act had once done—into complying with Ethel’s will. In short, it was a form of emotional blackmail.

But Judy’s feelings regarding Ethel were too deep-rooted and too complex to permit her to see anything clearly. Once more she had “misbehaved,” causing grievous results, and there was no longer any way to get Ethel to forgive her. It should not have mattered. But it did. For the rest of Judy’s life it mattered.

Somehow she managed to fly to the funeral, though doing so was entirely against the doctor’s orders. Midway through the service she broke down. Luft held her up until the end. Then, leaning heavily on him and another friend, Judy managed to make it to the car. Immediately afterward, she went to pieces and took to her bed. It was the beginning of a two-year-long relapse—the worst breakdown she had suffered or would suffer in her life. Any chance she and Luft might have had of a successful marriage appears to have been snuffed out during this period.

It was a lonely time and a monotonous time. She seemed to have been beaten back and deserted by the world. Luft was constantly away from home on business trips. Expecting the initial bonanza of her concert appearances to go on, he had not protected the huge sums she had made from the Palladium, the Palace, the Philharmonic, or the Curran. Her 1951 and 1952 income tax had gone unpaid, and as those had been peak years, the tax was astronomical—over $300,000. Once more she was immersed in debt, and in her present condition she could not imagine how she could ever rise above it. Her morale was never lower; and to add to this, whenever Luft was home, it seemed he had come there to appear in court to receive scoldings from a judge for not paying child support or alimony to Lynn Bari.

Luft began to press her to pull herself together so that she could work. Whatever his true motives might have been, the result did at least get Judy to her feet. She could not without returning once more to the pills, the crash diets. Luft now believed Judy should return to films in a package that they owned and in a film of which he would be the producer. If successful, it would establish him as a film producer and mean he could take over the family’s support. It was something to grab hold of for Judy. The immediate search for a film property began.

Back in the early 1940’s, Judy had done a great many radio shows. In January, 1941, she had appeared on the CBS Silver Theatre program in Love’s New Sweet Song, for which she wrote the original script that True Boardman adapted for presentation. In December, 1942, she had starred on radio with Walter Pidgeon and Adolphe Menjou in the CBS Lux Radio Theatre adaptation of A Star Is Born. At the time she had felt it was the finest performance she had given, and it had led to her first yearnings to play a full-fledged dramatic role. She had, in fact, discussed the idea of her doing a remake of A Star Is Born for the studio at that time but was told a radio appearance was one thing, a film role quite another. She was too young and the image all wrong. In a way, though, thanks to the seed that performance had planted in her head, it had led to her starring in The Clock. Now it all came back to her.

If she was to do an independent film—why not a remake of A Star Is Born? Something must have clicked in Luft’s promotional mind. Instinct probably told him the property was right for Judy, but that it had to be a musical version. With that decision, he set about the first phases of getting such a tremendous production into operation.

27Up to the time of the publication of this book, Sid Luft has had only two films under his production aegis. Both were produced in the same year (1954) and at the same studio (Warner’s).

One film was the brilliant musical version of A Star Is Born directed by George Cukor, starring Judy Garland and James Mason. The other was a substandard Western entitled The Bounty Hunters, which starred Randolph Scott and was directed by André de Toth.

Directed by William Wellman, and starring Fredric March and Janet Gaynor, the original A Star Is Born had been a Hollywood classic and one of the film industry’s top grossers.

If it was Luft’s decision to petition George Cukor to direct this version with Judy, then, indeed, his contribution to the final product is insured. Cukor’s cinema is a subjective cinema, consistently exhibiting his exquisite taste and style. He is never fearful of a commitment and he is masterly in his direction of women. By 1954 he had already directed Katharine Hepburn in A Bill of Divorcement, Little Women, Sylvia Scarlet, Holiday, The Philadelphia Story, Adam’s Rib, and Pat and Mike (a very comforting knowledge to Judy); Garbo in Camille; Norma Shearer in Romeo and Juliet; Crawford in Susan and God and A Woman’s Face; Bergman in Gaslight; Jean Simmons in The Actress; and Judy Holliday in Born Yesterday.

Never having directed a musical (since, he has contributed Les Girls, Let’s Make Love, and My Fair Lady to that form), Cukor was hesitant about accepting the assignment. The Moss Hart script, however, was a literate and moving adaptation of the original (by Dorothy Parker, Alan Campbell, Robert Carson, and Wellman); and it dealt with actors, a subject that holds a large attraction to Cukor, who had used it in many films to very good advantage (i.e., The Royal Family on Broadway, Sylvia Scarlet, The Actress, Dinner at Eight, Les Girls, A Star Is Born, Let’s Make Love, and Heller in Pink Tights).

In A Star Is Born, Judy was once again to play a girl named Esther. Esther had also been the name of the character she portrayed in Meet Me in St. Louis—certainly her best performance in her Metro years. The coincidence appeared to be a good omen. The story dealt with the love affair and marriage of an aging, alcoholic movie star (Norman Maine) and the young woman (Esther Blodgett) who, in their first encounter, saves him from making a drunken spectacle of himself before an audience of his own peers. Later Maine discovers Esther has a voice with a quality of true greatness and helps her in her own climb to the top of film stardom, renaming her Vicki Lester. But as she ascends, he slips badly—drinking so heavily he has to be institutionalized. Vicki decides that to save Maine she has to give up her own career. Overhearing this decree, Maine martyrs himself and frees her by walking out of their elegant Malibu Beach house and drowning himself, leaving Vicki to continue her ascent to stardom.

The film was an important one for Judy in more meaningful ways than as a career vehicle. The story, which twelve years before had intrigued her as a dramatic opportunity, now bore a deep relationship to her own life. The more she studied the script, the more painful, the more impossible it became for her to chance losing it. The peregrinations of her mind might seem difficult to map but not in the final analysis to understand, for the script enabled Judy to play out two of her own fears and fantasies. She was at one time both Norman Maine—the star who in a desperate need for love devoured all those around him—and the great star’s “lover,” giving completely, unselfishly, and with complete understanding. She had great compassion for the character of Maine—the great star who was alternately being called a has-been and then having to fight the terror of one new comeback after another; the great star who could not fight his greater weakness (alcohol) and so allowed it to become his excuse, his crutch, and in the end, his true executioner. By playing Vicki Lester (Esther Blodgett) she was able to show the world how self-sacrificing love must be if one does love such a star. In the melodramatic but moving last part of the film Norman Maine commits suicide to save those he loved. It was a romantic notion, but from that point forward in her life Judy would consider that possibility many times.

She had been off the stage two years, away from films four years; and though her last film, Summer Stock, had been a success and her last concert a smash hit, the press now treated her as a has-been and she had suffered the poorest public relations. It had started with Ethel’s interviews; and had been compounded by Ethel’s court case and untimely death. But Judy’s public image seemed smashed beyond repair more by the airing of all her financial woes than by anything else. She did, indeed, appear a spoiled, unthinking, irresponsible woman. She had made more money in one year than any newspaper reporter could have dreamed of making in a lifetime, and she had spent it foolishly—and not paid her taxes—which reporters most assuredly had to do each year. Edema had given her a bloated, drunken look. It was insinuated that Judy Garland was an alcoholic and that the reason she had not appeared in two years was that no management would risk a drunken performance.

The fears, the fantasies—they were a Garland pattern; and they were the basis of Norman Maine’s character and of Judy’s strong identification with that role. They were the impetus that gave her own role such force, poignancy, and urgency. She had to convey to the world how much Norman Maine must be loved and accepted. She had to make the public understand how lonely and cold it was at the top. In essence, her stunning performance of Vicki Lester (Esther Blodgett) was a closing plea before a worldwide audience for her own defense.

Cary Grant was initially set to play Norman Maine. It was fortunate for the end product of the film that his own good sense caused him to withdraw. It would have been unreal for an audience to believe that Grant—the suave, million-dollar movie idol who was known to be a health nut—could be an alcoholic has-been. Ray Milland had done it in The Lost Weekend, but Milland’s screen image had not been so well established as had Grant’s. James Mason was cast. It was a brilliant and successful choice. Mason’s portrayal stands out as one of his best in a career filled with great performances.

In all her Metro years Judy had never been given the opportunity to submerge herself completely in a role, for no part had demanded that of her. She had been able to rely on a simple understanding of the character she might be playing (for they were never deep or complex). By interpreting the character with a basic honesty and being able to graft her own personality onto that character, she had been totally believable even in the most inane of roles. Vicki Lester was her first true challenge as an actress. (The Clock had been a departure, and Meet Me in St. Louis, sensitive; but neither performance had demanded so much of her.) Not only was the role complex, but her own need to be Vicki Lester and to convince her audience of the honesty of Vicki Lester’s great love and of the sincerity of her intention was of a very complex nature.

Norman Mailer, in Marilyn, attempting to throw light on that star’s ability to become a character she was playing, states:

In the depths of the most merry and roistering moments an actor can have on stage there is still the far-off wail of the ghoul. For a good actor is a species of necrophile—he makes contact with the character he is playing, inhabits a role the way a ghoul invests a body. Indeed, if the role is great enough, the actor must proceed through a series of preparatory acts not unrelated to magical acts of concentration, ritual, and invocation.

So, as the first days of shooting passed, as Judy became more and more mesmerized by Vicki Lester, as Vicki Lester began to take over from Judy Garland—the torment, the concentration, the invocation that was to plague her for the long, long duration of the film’s production began. Every night before a scheduled morning scene she would have to more or less invest Vicki Lester’s psyche in her own. And all the time this terrible confusion, this first identification with the role of Norman Maine was there to haunt her. Vicki simply could never sway in her love and devotion for Maine. If she did, somehow it was a betrayal of Judy’s own self; for after all, she was also Norman Maine. And the deeper she got into the film, the more inevitable Norman Maine’s—and, therefore, her own—destruction and suicide seemed to be. It was a harrowing and debilitating experience, and there were nights when the exhaustion overwhelmed her and mornings when she simply could not face the pain of the scene she was to play.

Within a few weeks of the commencement of photography, the trouble began. She had had to submit to a crash diet before she stepped in front of the cameras. Diet pills and sleeping pills once more became a pattern and were interspersed with the severe emotional highs and lows of her performance; the extreme hard work the part required; the tough, unrelenting direction of Cukor; and the total professionalism of James Mason. Then came the incredible decision to reshoot the entire first month’s footage in Cinemascope. From that point, Judy, though she was the only one to adamantly object to this scrapping of a full month’s work and starting over, had Luft always at her heels, pushing her on, giving her no chance to stand still. In a unique agreement, Luffs deal with Warner Brothers stipulated that the entire negative cost of the film be recouped before he and Judy received their share. Originally budgeted at $2.5 million, by the end of principal photography the film’s cost had soared to over $6 million. Luft and Judy were broke during most of the production and deeper in debt than ever at the end; and as the cost rose, so did Luft’s desperation.

The pressure was felt by everyone connected with the film. Some broke beneath it. Hugh Martin, who was the arranger and composer for the film, walked out. (Harold Arlen and Ira Gershwin did the final score with special outside material by Leonard Gershe and Roger Edens. This was the famous “Born in a Trunk” number which Luft had bought outright for Judy.) In all, five cameramen and four costume designers also walked off the film; and new key people had to be found who could still maintain a sense of continuity to the production.

The press had a holiday. Judy was once again, as in the past, blamed for all the problems a production was having. Finally Judy confronted the reporters. “I’m a little tired of being the patsy for the production delays on this film,” she told them testily. “It’s easy to blame every production delay on the star. This was the story of my life at Metro when I was a child actress. When some problem came up and they couldn’t lick the delay, no matter who caused it, it was always blamed on the star. Whoever was responsible figured that the star could get by without a bawling out. They couldn’t.”

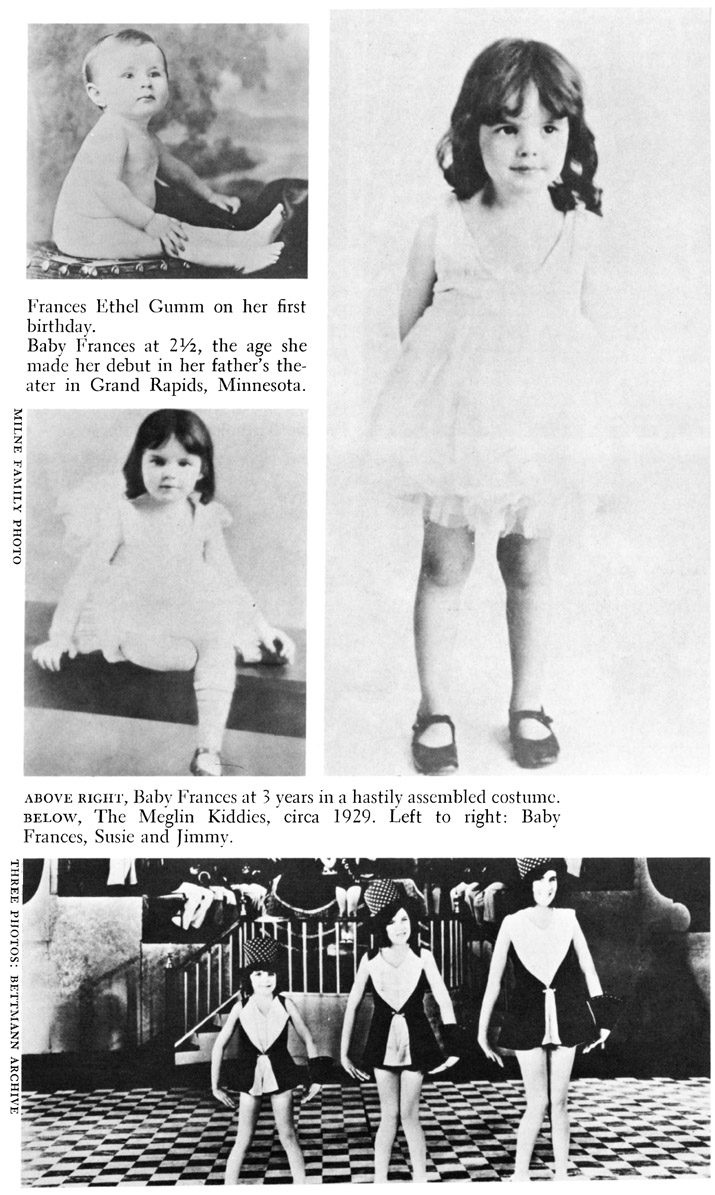

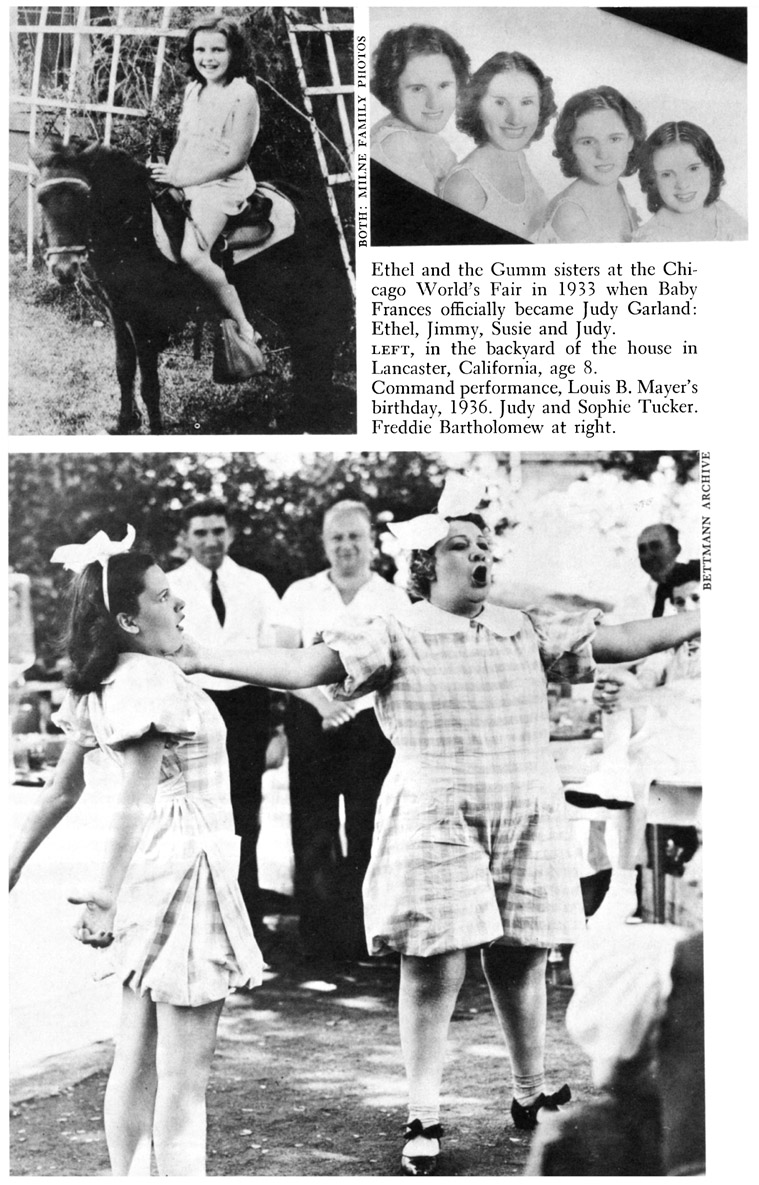

Cukor at least had a sense of humor. “First they said it would never start,” he commented, “then that it would never stop.”