During the bad days I’m sure I would have perished without those wonderful audiences. Without that and a sense of humor, I would have died ... I think there’s something peculiar about me that I haven’t died. It doesn’t make sense but I refuse to die.

—Judy Garland

34“When I was eleven,” Liza says, “I was hiring Mama’s household staff. God, it must have been hilarious. Out comes this eleven-year-old kid and says, ‘May I see your references, please?’” Liza was now twenty, and she had been so old, so responsible so long that it seemed she had never been a teen-ager. At this stage she was, in a sense, the mother of the family. Extremely loyal to Judy, she was, as well, fiercely devoted to keeping the family intact. There was a high degree of camaraderie between mother and daughter, and the similarities between the two extended deeper than the arched body and outflung arms both employed to end a song, or the quavering high notes and deep-throated sadness in their voices. They shared a marvelous sense of humor, binding love, career dedication, and the enigma of continually reaching out to grasp life and just as constantly withdrawing from it.

Both had quick-to-rise, emotional temperatures, and neither could veil the truth. There were volatile blowups between them even when Liza had lived at home, times when Judy would lock Liza out of wherever they were living and Liza would stand outside the door until, finally, Judy would open it and they would fall into each other’s arms crying. It was during one of these lockouts that Liza left for New York (she was sixteen at the time), having saved enough money for her fare and $100 extra. She never returned “home,” nor did she ever again ask for support, for the next two years living first in the Barbizon Hotel for Women (“I went bananas!” Liza comments about that experience); spending two nights on a park bench in Central Park; and bedding down on a friend’s couch for the rest of the time.

The Palladium appearance had briefly reunited them, but it had been a worrying experience for Liza and a shock to both mother and daughter—for Judy suddenly realized she had a grown-up daughter and, as Liza comments, “She became very competitive with me.”

But Judy was eventually able to push back the competitiveness she felt. Liza held a very special place in her life. And at the same time, Liza was responsible for some of the guilt she suffered. If she could have done it all over again, she would have—just so it would perhaps have been different for Liza. So she did try to contribute what she could to Liza’s happiness. Liza was a professional in her own right, and Judy did not hesitate in helping her.

In a New York Times interview with Tom Burke (December 7,1969), Liza reveals the following episode:

I was up for a television show, Ben Casey or something, and the part was a pregnant girl who had had an abortion that had gone wrong and she’s in the hospital. I knew how I wanted to see it, but not how to be it. So I sort of gingerly took the script to Mom, and said, you know, “Mama, help me.” We sat down on her floor, and she said, “Now, read me your lines, and the doctor’s lines, both.” His line was, “Did you want to have the baby?” I read it and Mama said, “All right, he’s a doctor, he isn’t getting personal—but how dare he intrude on you, how dare he ask you that, how dare he be there, how dare you be in the hospital, if only you could have married the father, if only he’d loved you, which he didn’t. Now, did you want to have the baby? ! ! ! J” All I had to say was, “No,” but it came out right. Because she had given me the thoughts—the pause, not the line. Then she said, “Read me his line again,” and I did, and she said, “Now this time you are going to concentrate on not crying. That’s all you have to worry about, not letting him see you cry. Your baby is dead, your life is ruined, but you’re not gonna cry, you’re a strong girl, your parents have told you, your teachers have told you, you know it, you know it, you’re not going to cry!” And my “No” came out even better. She taught me how to—fill in the pauses. And if there’s a way I act, that’s the way. From that one day there on the floor. And now, if maybe another actor will say, “What are you using in that scene,” I’ll say, “Well, I’m playing that I’m not gonna cry.” They say, “Whaaat?” But I know!

But Judy’s concern for Liza’s career was not as strong a force as her fear that Liza might not escape her own pitfalls. “Watch my mistakes,” she would warn Liza. Liza seldom drank and did not take drugs, being adamantly opposed to even common pills such as aspirin. Dean Martin’s daughter Gayle has said, “Rather than a fear of what drugs can do to you, Liza has a knowledge.” Liza was fighting at a very early age to ward off any dark maternal patterns.

While on her ill-fated Australian tour, Judy had met a young, attractive Australian singer-comedian, Peter Allen, and had encouraged him to come to the States, promising him a spot in her nightclub act. The following year, Allen was in London at the same time as both Judy and Liza. Judy now saw this young man as the white prince come to rescue Liza. Perhaps she was attempting to live vicariously through Liza, but she considered it a good, maternal, loving gesture to introduce the two young people and was pleased when she observed a mutual attraction. Judy turned her attention to Lorna and Joey, heaping perhaps more on Joey than on Lorna because Joey always seemed to need more. He was less self-sufficient, less coordinated, a poor student. But it was Lorna who Judy truly believed would someday be the second-generation star, not Liza.

But to say the children occupied her mind entirely in the years between 1960 and 1967 would be a complete untruth. Judy was occupied mainly with the very essentials of survival. Her drug addiction was destroying her body, and the parasites were undermining her future. Once again she could not call her soul her own. Once again she turned in desperation to the nearest man who offered help. And once again that man was Sid Luft.

And it seems incredible, but by 1967 Judy was again hopelessly in debt—and that in spite of the impressive salary she had been paid by CBS and the fact that she had appeared in concert at a high salary very frequently. With the exclusion of the periods of time when Fields and Begelman were in charge and when Mark Herron was part of her life (1961-65), Luft was never far from her side. However, let it be said that Judy, through her sporadic dependence on Luft, encouraged the situation.

Repeatedly, close observers have stated that there were times when no one else but Luft could get Judy onstage or keep her there. Though she was out of love with him in the physical sense and highly resentful of his associate, Vernon Alves, she nonetheless felt rooted to Luft. He was, after all, the father of two of her children, and she could not believe that his intentions were other than to protect his family, even when she was devastated by his actions. There was also a pattern that had established itself very early in her life, back in the days when she was on the road with Ethel. She was expected to be the family supporter and all others were accepted in the role of dependents who did everything within their power to help keep her working. They did so in pursuit of their own survival as well. A pattern of threat and rejection if she erred—and reward if she behaved had also been vested. Therefore, though it might seem inconceivable that after all the anger and disillusionment and hostility she had suffered with Luft she could reunite with him in her career, it was not an illogical action in terms of her well-entrenched behavior pattern. How many times had she felt the same things about Ethel? About L. B. Mayer? About Minnelli? And in varying degrees, about all the people in her life who had been aboard the Garland bandwagon? But the most poignant, crucial, and fundamental fact to remember was Judy’s total dependence upon those close to her. They were her lifeline to the outside world and they were the only comforters in her distress.

By 1967, Judy was fully aware not only that she was hooked, but also that her body was moldering, necrosis setting in to each vital part. Where once she had thought in desperate moments of ending her life, she now hung on to any outstretched hand that might promise to keep her afloat. She became almost savage in her desperation. A quiet, ferocity overtook her actions and responses. Her nails would tear like tiger’s claws into the palm of anyone who meant to leave her; her demands became insistent threats; she was a very frightened, terrified lady.

Not only was all the money she had made gone by ’67, not only was she in debt—she was several hundred thousand dollars in debt, most of it again to the government. The pattern had repeated itself. Her earnings would go to her managers, but her taxes and many of her road expenses would not be paid; nor was she ever trusted with any of her own earnings. Now she was back in a position in which the government could seize her earnings as she made them, leaving no money for her. Something drastic had to be done, and Luft was right at her elbow to insist it be done his way.

Two years later, Judy gave a deposition to a London court about the circumstances existing in her life during the spring of ’67 and about the Group V contract that Luft proposed, had drawn up, and had her sign. The following, a direct excerpt from Clause 4 of this deposition, given by Judy in the High Court of Justice, Queen’s Bench Division, on December 29, 1968, and signed by Judy and by a Commissioner for Oaths, is presented verbatim so that some clarity can be given to the murky transactions that were to come:

. . . The alleged contract with Group V Limited came into being in June 1967 when I was approached by Mr. Sid Luft to whom I had formerly been married but from whom I had then been divorced for some four years. He suggested to me that an organisation should be set up to be called Group V, the “five” to consist of me, my daughter Lisa [Liza] Min[n]elli, the two children of Sid Luft and myself and Sid Luft. He explained to me that Group V would act as agents and representatives, pay us reasonable living money and enable us to build up trust funds for the children and otherwise obtain financial security. He also explained that there would be certain tax advantages. I accepted his suggestion and he then asked me to sign. He gave me one page to sign and as I trusted him I signed it. I was in a hurry to travel to a performance. I was subsequently shown the complete contract in which the first fifteen pages had been put in front of the page which I had signed. I was then told that Group V Limited did not include my children and myself but rather Sid Luft, Raymond Filiberti, and three other persons whose names I cannot remember. Despite the circumstances I continued to work for Group V because they had by that time made many advance bookings for me to appear and I felt that I was under an obligation to the audiences who were expecting me to appear. I continued to fulfill bookings made for me by Group V for a year after the contract was signed and a further two months after that. I mention the further two months because I had expected to receive from Group V some form of letter or notice renewing the contract but to my knowledge no such letter or notice ever reached me. I was waiting for such a letter because it would have given me an occasion to deal with Group V because throughout the year after the contract was signed I had fulfilled engagements made by Group V but had received no remuneration from them. I would find in each case that Group V had made the booking and received payment and that I would be left to appear and not be paid. At no time during the period of fourteen months mentioned above did I receive any payment at all from Group V in respect of the moneys I was to receive under the contract. I only continued to fulfill engagements which they had made in the knowledge that they at least were being paid and that I was entitled to an accounting from them. I was thus at least working and meeting obligations to the audiences.

Not only was I not paid but Group V failed to pay my expenses. A large quantity of my baggage was impounded in New York because Group V failed to pay my hotel bill. In December 1967 I met an engagement in Las Vegas and was then booked to appear in New York. I had no money of any kind and was obliged to borrow. I asked Filiberti for a loan as he knew I had not been paid and he gave me a cheque for $2500 drawn on his bank in New York. I flew immediately to New York but on presenting the cheque found that payment had been stopped.

Raymond Filiberti and two men named Leon Greenspan and Howard Harper were to play a Machiavellian role in the last year of Judy’s life. Filiberti had a police record. Greenspan and Harper were acquaintances to whom Luft owed a large sum of money. Harper, whose real name was Howard Harker, also had a long police record and had been found guilty by the State of New Jersey on various dates of disorderly conduct and of strong-armed threats.

But in June of ’67, Judy had never heard of any of them. What she knew was that she could not be alone, nor could she deal with any business problems or financial pressures; and Luft was there by her side assuring her that if she signed the paper he was handing her, she need not worry about anything except her performances. Her desire to trust him overriding her sensibility, she signed.

One is inclined to believe that Judy’s respect for authority and the law compelled her to be as truthful as memory permits in her deposition. Presuming that to be so, the contents of the fifteen pages that were placed before the page containing Judy’s signature (on which appear only Judy’s and Luft’s signatures and one sentence—“In witness whereof, the parties hereto have executed this agreement as of the day and year first above written”) constitute a diabolical travesty of personal rights. They contain twenty-six clauses, each of them designed to rob Judy of any rights in her own career, no matter what path that career might take. She was, from the date of the contract, owned by Group V in a prohibitive and exploitative fashion—was chatteled to a group of suspect men whom she did not even know.

The Group V contract had Judy sign away all rights in and to not only her services as a performer but “any and all incidents, dialogue, characters, action, material, ideas and other literary, dramatic and musical material written, composed, submitted, added, improvised, interpolated and invented by Garland pursuant to this agreement” and granted the Corporation without limitation rights to “transmit, publish, sell, distribute, perform and use for any purpose, in any manner, and by any means, whether or not now known, invented, used or contemplated (specifically including, but not limited to), by means of motion pictures, radio, television, televised motion pictures, printing or any other similar or dissimilar means all or any part of the matters and things referred to in this article.”

In Clause 13 of the contract Judy is denied the right of free speech:

Garland will not at any time without the Corporation’s prior written consent issue or authorize the publication of any news stories or publicity relating to her employ-men hereunder or to the Corporation. . . .

But perhaps one of the most bizarre clauses in the agreement is Clause 17:

As used in this agreement, the term “incapacity” shall be deemed to refer to any of the following events occurring at any times during the term of this agreement: the material incapacity of Garland arising out of her illness or mental or physical disability or arising out of any accident involving personal injury to Garland; the disfigurement, impairment of voice or any material change in the physical appearance or voice of Garland, the death of Garland; and the prevention of Garland from rendering services by reason of any statute, law, ordinance, regulation, order, judgment or decree.

Garland will give the Corporation written notice of her incapacity within twenty-four (24) hours after the commencement thereof, and if she fails to give such notice, any failure of Garland to report to the Corporation as and when instructed by the Corporation for the rendition of her required services hereunder may, at the option of the Corporation ... be treated as Garland’s default.

This meant that Judy would be held responsible for any loss of income to the Corporation if she could not fill a commitment because of, for instance, a stroke, or any serious and sudden illness, and that her estate would be held responsible in the case of her death unless a twenty-four-hour notice could be given!

When Judy signed the Group V contract she was hopeful that some of her problems would be solved by its existence. Instead, from that date to the end of her life, it was to cause her privation, humiliation, and a shattering of her self-dignity.

35Her world was now a sky crowded with dark and threatening clouds. When one came close enough, the clouds were seen to be clusters of maggots. They swarmed about her in the nighttime because she had come to be a nocturnal creature. Not that she liked the night. She feared it with such an intensity that she could not sleep until it had passed; nor could she be alone—or in the dark. All night, where-ever she was, the lights would blaze and the radio would blast and there would be people making her drinks she seldom touched, drinking her liquor, milling about, feeding their own convoluted dreams on her desperation.

Liza was living with Peter Allen in an apartment in central Manhattan. Her career was zooming ahead and she was very much occupied. But Luft, on the road again as Judy’s manager, did not complain if she kept Lorna and Joey. Liza has said of her early years that it was difficult to know who was mother and who was daughter. The pattern was repeating itself with Lorna, whose maternalism overlapped her mother’s and encompassed her younger brother. In 1966-67 they really had no home and were constantly on the move from one hotel to another. Judy still controlled the mortgage on the Rockingham Drive house, but its ownership was in serious jeopardy.

Mickey Deans came into her life as early as 1966, though they did not get together until more than a year later. Deans was managing Arthur, the fashionable discotheque owned by Sybil (the ex-Mrs. Richard) Burton. He had been a pianist at Jilly’s, a well-known local bar that had always attracted famous theatrical personalities. He was a good musician, very personable, an ardent conversationalist with a winning small-boy smile—the kind that said, Yeah ma, I’m guilty, but I love you and I didn’t mean to do it! He was very ambitious. Perhaps his job at Arthur was tough for him to accept in view of his showbiz ambitions; but he fed upon the knowledge that he was where the action was—and he was able to meet the top celebrities and entrepreneurs in New York City.

His world was also a nighttime world, a world of wild music and frenetic sound, of booze and pills, of theater people, gay people, prostitutes, celebrities, musicians, the hangers-on and the con men. And his world did not shut down until four in the morning, at which time he was too wound up to go to bed.

In an article he wrote for Look magazine, Deans describes his first meeting with Judy at a time when Judy could not pull herself together to fly to a performance.

I first met Judy Garland in 1966. A mutual friend called me from the West Coast and asked if I would take an envelope to be delivered to me by a doctor over to Judy, who was in trouble at the St. Regis Hotel in New York.

I agreed, and a little later, a doctor dropped by Arthur, the discotheque I was then managing. He left a small package with me, and I took it to Judy. When I knocked on the door of the hotel suite, it was opened by little Lorna Luft. Behind her stood her brother Joey, eyes wide with fear and apprehension.

Judy stood across the room. Her hair was undone and obviously graying at the roots. She was wearing a cocktail dress but no shoes. In an attempt at graciousness, she started woozily across the room only to trip and fall across an ottoman. We both laughed, and this relieved the tension. As we smiled at each other, I heard Lorna telling Joey not to worry as this was the doctor.

I gave Judy the envelope, which contained “ups,” pep pills. She popped them into her mouth along with some of her own pills, pulled herself together and made the plane she had been in danger of missing.

Deans was not to see Judy again for quite a time, and by then she had blocked out the circumstances of their first meeting as she had been able to block out most of the unsavory day-by-day happenings in her life at this period. During the long, torturous months that were to intervene, she was, however, seldom alone. Luft and Alves, after the signing of the Group V contract, were at hand when a concert was imminent and during a performance. Bobby Cole had come back into her life as musical director, and he and his wife, Delores, were always on call. There were to be two semiserious romantic liaisons: with Tom Green, who also functioned as a publicity assistant to Luft and Group V, and with John Meyer, who was likewise involved in publicity; there were those members of the Garland Cult who called themselves “The Garland Group” and who lived vicariously and by any means, simply to be close to Judy; there were the various doctors who ministered to her; and there were members of her public relations firm.

In the spring of 1967, Judy came to New York and stayed at the St. Regis. It was a very joyous occasion: Liza and Peter Allen were to be married. But also, she had been cast in the film version of the best-selling Jacqueline Susann novel Valley of the Dolls. The role she had signed to play was that of Helen Lawson, “an aging queen of Broadway musicals who had the talent to get to the top—and had the claws to stay there.”

A press conference was arranged at the hotel by Twentieth Century-Fox, which was producing the film. “So I’m cast in the part of an older woman,” Judy told the press. “Well, I am an older woman. I can’t go on being Dorothy for the rest of my life.”

John Gruen, interviewing her for the New York Herald Tribune in the chaotic shambles of her suite at dinnertime, asked her how she felt about being called a legend. “If I’m a legend, then why am I so lonely?” she shot back.

He observes:

. . . She stood rail thin, her sleeveless black dress emphasizing the thinness. Her face is gaunt; the eyes enormous. There is electricity in her presence, but she seems disconnected just now. She reels around a bit, her speech comes in splutters, but she is cheerful, friendly, apologetic for the mess . . .

. . . Suitcases are open on the beds. Clothes hang from hangers or lie on chairs and couches. Phonograph records, mainly of Judy and Liza, are strewn around the room, there are flowers, letters, bills, messages, photographs and empty glasses on the various tables of the three room suite.

She had just heard the news that the banks had foreclosed the mortgage on her Rockingham Drive house and her furniture and private possessions were in danger of being lost. The news had come while Gruen was interviewing her. “Well,” she joked nervously, “if worse comes to worse, I can always pitch a tent in front of the Beverly Hilton and Lorna can sing gospel hymns! That should see us through. . . . Lorna is already showing signs of becoming a fabulous singer.” She added, “I think Lorna will make it very, very big one day.”

According to Gruen, Lorna, then fourteen, pale blonde and blue-eyed like her father, stood close at hand during the interview, as did eleven-year-old Joey, his dark, slender face shadowed with private concern. Liza, the Coles, Tom Green and assorted others were present. Judy was not shy about discussing the truth openly.

“Why should I always be rejected?” she inquired. “All right, so I’m Judy Garland. But I’ve been Judy Garland forever. Luft always knew this, Minnelli knew it, and Mark Herron knew it.”

Judy left New York to continue work on Valley of the Dolls, accompanied by publicist Tom Green, who was being referred to as her “fiancé.” From the very beginning, Judy felt accepting this role had been a mistake. The further she continued into the film, the more convinced she was. With an instinct that the film could do nothing for her career and that in the end it would be a commercial but dirty film, she decided to do what she could to get out of the contract. A curious dichotomy of values and morals guiding her actions, she refused to appear on the set when she felt that a scene was either dirty or that she did not believe the dialogue. There followed accusations that these “delays” were caused by her drug addiction and her drunkenness. It certainly was true that she was as reliant as always upon the pills (she was not drinking, however) and that the daytime work schedule of a film caused a difficult imbalance to her nervous system, but Judy, unless physically incapable (and a translation of this phrase would mean totally unable to stand on her feet), could always fulfill a commitment if the drive—the true desire—was there.

Having relied on others in the decision that she appear in Valley of the Dolls, she had been guilty of not reading the script until the cameras were ready to roll. When she did, she was appalled. “That very strange Jacqueline Susann doesn’t seem to know any words with more than four letters,” she commented, adding, “I just can’t stomach it.” And the night before she was to shoot her first scene, she tersely said of Helen Lawson (her role), “That broad has a dirty mind.” After the scene, which involved a confrontation with Patty Duke as Neely, she cracked, about Miss Duke, “That broad has a dirty mouth.”

She wanted a release from her contract, and since the studio refused to give it to her, she in turn refused to appear before the cameras. Finally, the studio was forced to fire her, paying her $40,000 in settlement and replacing her with Susan Hayward. (The film subsequently did very little for Miss Hayward’s career.) She was also given the $5,000 sequined paisley pants suit that Trevilla had designed for her to wear in the film. The suit—which was as spectacular as it was heavy and almost painful to wear—was to become a major costume for all her future appearances.

Shortly thereafter, Judy signed the Group V Ltd. contract and Luft booked her on a backbreaking musical tent tour during the hot months of June and July, ending with a stand at the Westbury, Long Island Music Fair, where the box office took in a record-breaking $70,000 in six days.

On July 31, 1967, Judy, under Luft’s auspices, appeared for the third time at the Palace in a Group V Ltd. production called Judy Garland, At Home at the Palace. It was a family affair. The program proclaimed that “During the course of Miss Garland’s performance she will introduce her protegés, Lorna and Joey Luft.” Luft’s staff included Vernon Alves, Assistant to the Producer, and Tom Green, Director of Public Relations for Group V Ltd. Appearing with Judy were the immortal black vaudevillian John Bubbles (the original Sportin’ Life in George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess), who had shared the bill with Judy when she had appeared at the Met; comedian Jackie Vernon; and a former Ringling Brothers-Barnum & Bailey Circus star, Francis Brunn.

She entered from the back of the theater in the now-famous sequined pants suit, looking fragile (she weighed ninety-six pounds), “jogging down the aisle, hugging admirers, shaking hands and just plain shaking” (Time, August 18,1967).

“This is going to be an interesting performance,” she told her audience from the stage in a hoarse voice, “because I have absolutely no voice. But I’ll fake. Oh well, maybe I’ll hit the notes because you’re so nice and because it’s so good to be home.”

“I love you, Judy,” screamed a man from the balcony. “I love you too,” she called back. Then, moving to stage center, looking like some lost but beautiful blue jay on that vast stage, and singing in a warm and certain lower register, she opened the show with “I Feel a Song Coming On.” It ended in a powerful crescendo, and after the wild applause quieted she laughingly commented, “My! I’m a loud lady!” She struck a saucy hands-on-hips pose. “No crooner I,” she added.

Later in the program she asked the audience, “What should I do now?”

Again shouts from the balcony and a man’s voice, “Just stand there, Judy.”

“I get too scared to stand here,” she replied. “Guess I’d better sing.”

And sing she did, belting out the old favorites, bringing a terrible intensity to songs like “The Man That Got Away” and a moving poignancy to “Over The Rainbow.” She was in rare form—much of the old Judy was on display—and there were shrieks and bravos when she made her first exit. “Don’t ever go away,” her audience shouted. She cried as she lifted the mike from the stand and held it trembling and close to her mouth, brushing tears away from her cheek with the other hand. She looked totally drained, ill, her cheeks flushed as if with fever. The costume she wore appeared to have become intolerably heavy for her and she to have shrunken inside it; the flashing sequins in the spotlight made one think of a lizard about to shed its skin.

“Thank you, God bless, I love you very much,” she said in a croaking, tired, emotionally spent voice. The audience began its surge forward, reaching out for her tenderly, as if to touch the last frail leaf of November.

“Audiences have kept me alive,” she confessed, and then leaning in close, confiding, “Everything I want is right here,” she told them.

In the audience that night and seeing Judy for the first time was nineteen-year-old Edward Baily III. He was a young man on the edge of despair. He had not been a dedicated Garland fan, had never seen her in concert, but he had heard her on records. Somewhere about midway in her performance he says, “I don’t know what happened—but I was hooked.”

After the show he raced around to the stage door, where about two hundred other Garland fans were gathering, standing there until two in the morning, when Judy left the theater. He drew back so that she wouldn’t see him, feeling she must not think of him just as a fan.

Judy had been in good form that night, and though one could not say either the performance or the audience had risen to the evangelical frenzy they had at the Carnegie Hall concert, still the divine winds of revelation seemed to sweep from the stage to the last balcony of the Palace that night. Baily uses the word “hooked” as one might refer to an introduction to a drug or to a religion. He had gone to the theater as one might, in desperation, approach the tent of a faith healer—and for him, the miracle had occurred. Having never seen Judy in a film, Baily’s sole identification was with a middle-aged woman more than twice his age. Judy, by seeming to be able to see past all exteriors and into the soul, became the fantasy mother of his dreams. From the moment he became “hooked” he had been at-the-ready to do her bidding.

At the Palace stage door, Baily met, for the first time, the Garland Group. He and they were an instant brotherhood. Standing together for hours in the hot night waiting for Judy, they shared thoughts and confidences. Baily was immediately taken in, made au courant with all of Judy’s trials, and apprised of all the “members of her court.” According to Baily, it was implicit that one treated all of Judy’s round table with as much persuasive charm as could be mustered. What Baily had found was an adhesive, conjunctive, symbiotic relationship that encompassed all the members of the Garland Group and Judy as well. For the first time in his life he felt accepted, a part of a family.

When Judy did leave the theater that night, Baily was moved by her smallness, her apparent exhaustion. He knew he was now pledged to remain close to her and that he must both cheer her and protect her at the same time.

36“I can live without money,” Judy said, “but I cannot live without love.” That was the symbology beneath the public announcements of “enduring love” for all the young men who shared her last years. It was like shouting, “I am not afraid!” as loudly as she could in a cavern of echoing darkness. By loudly proclaiming, “I am loved; I am in love,” Judy could, for short periods, convince herself that this was the truth.

In her public disapproval of Arthur Miller—“I don’t approve of Arthur Miller,” she had stated to the press, “because I don’t think he understood Marilyn Monroe very well”—she revealed the true raison d’être for each disenchantment. She had finally come to believe that Mark Herron did not understand her. Now she was certain that was true about Tom Green.

There was a great deal of newspaper coverage involving some rings that Judy claimed Green had stolen. It is more likely that Judy had given him those rings when she was in a drugged state and that at a later date, feeling misunderstood, could not recall giving him the jewelry. The problem was finally resolved out of court, but the Green-Garland liaison was over. According to Judy it had never been an important relationship, but the twenty-nine-year-old Green had been a steadying influence for over six months, and members of the “circle” and of the Garland Group claim Green was the only man they knew who had tried to wean her off pills. Judy was in the state she considered “intolerable”—she was attempting to live without love. A new young man, John Meyer, entered the scene, but this too was never to become an intense or meaningful relationship.

One night, after a Palace performance and with Judy still dressed in the sequined pants suit, Bobby Cole took her to an elegant Manhattan restaurant—where she was refused admittance because, in those days, it was still considered a breach of etiquette for a woman not to wear a dress. She was more amused than angry, but she did not feel like going back to the hotel. Cole called Mickey Deans and asked if women in pants were permitted at Arthur. Deans told him to bring Judy right over and was waiting at the door when they arrived. Judy appeared not to recall that they had previously met and Deans did not remind her, but there was a warm and instant interchange between them; Deans sat with her until after four in the morning, although Arthur had closed hours before. But Deans was, at the time, deeply involved in another relationship, and although there was a mutual attraction, and they found they both liked and laughed at the same things (Judy was most struck by Deans’s easy ability to laugh), a tacit understanding that the time was not yet right passed between them.

After the Palace there were a series of concerts across the country that Luft, acting for Group V Ltd., arranged. Early on, Judy became aware of the shoddy deal she had received. But there seemed no one to turn to and little she could do to extricate herself from the situation. For though quite often during this period her hotel bills were unpaid, she was being supplied with the necessary pills to feed her habit. Legally, there was no way to obtain twenty to forty pills a day, and Judy was incapable of dealing with the situation on her own.

But on the second night of a stand at the Back Bay Theatre in Boston, she refused to leave the hotel for the theater. Some two thousand fans were both disappointed and disgruntled. “Too many things have happened in the past. I couldn’t come,” Judy said to the press through a lawyer, Barry Leighton, but she did not elaborate, and Luft, with no apparent care about Judy’s public relations, contradicted a statement by the theater management that Judy had been ill and made a point of declaring that he did not know why she did not appear and that “. . my ex-wife was in good health the last time I talked with her, which was a few minutes before she was scheduled to appear at the theater.” What had really occurred was that Judy had become aware of the gross exploitation of her, due to the Group V contract and was questioning Luft on it. She was now demanding that Luft arrange to pay her before each appearance. And Luft, under financial duress, was juggling the money to appease the government, Judy’s creditors, his own creditors, and Judy.

Throughout what was to be her last American concert tour, the Garland Group was constant—traveling by any means possible to get to her concerts, cheering her on, waiting for her after the shows, remaining in the lobbies of her hotels as though on guard.

Ed Baily never missed one performance. He was, by now, totally dedicated to Judy, and even Judy was becoming aware of his dedication. It was, in fact, going to be impossible for her to be unaware of it, for at each performance Baily managed to have either yellow or pink roses (her favorites) delivered to the theater for him to carry up onstage and present to her at the end of the concert. She assumed Baily was a young man with some personal income that allowed him to “travel with” her (Baily’s phrase—and as explained by him, meaning on the same train or plane, stopping at the same hotel; but never in an authorized capacity or in the same company as Judy) and to overwhelm her with roses.

In one year’s time Baily sent Judy $100,000 worth of roses. (Christmas, 1967, he had a large Christmas tree designed and made entirely of pink roses and presented it to her onstage.) He sent roses not only to Judy but to all those members of her entourage whom he felt he must win over in his bid to enter their private circle. Long-stemmed roses were then about $15 to $18 a dozen, and never did he present Judy with less than five dozen.

In late 1967 and early 1968, Judy’s performances left a great deal to be desired—leading Variety to comment: “Nagging question is how long can Judy Garland keep it up. How long does she want to? Audience affection and good will are there, but there can be a limit to how long folks will watch a well-loved champ gamble with her talent.”

She appeared to be down once more. She was booked into the Garden State Arts Center in Holmdel, New Jersey, from Tuesday evening, June 25, to Saturday evening, June 29. She had a new conductor, twenty-two-year-old Gene Palumbo, and Lorna and Joey were appearing with her along with a group called the Tijuana Brats.

She stepped out onto the immense outdoor stage with the four thousand people in the audience not knowing what to expect. It was hot and she was perspiring and in her “sequined uniform.” She weighed ninety pounds and looked pale, but it was one of those evenings to be remembered. (Critics claimed it was her best performance in ten years.) She belted or caressed twenty songs and, according to The Asbury Park Press, “. . . carried a non-stop show with grace and charm, despite the moths buzzing around her face, the strings hanging from her sequined pants suit, and a too bright spotlight to which she complained, ‘No lady likes to be seen in that light!’ ”

The audience went wild and flocked to the stage at the end of each song; they jumped up and down on their seats; they screamed, “Bravo!” and “We love you!”

She pranced out onstage at the ten-fifteen opening with “Once in a Lifetime.” Her short hair was drawn back behind her ears, only a stray lock falling on her forehead. Tucked into the loose neck of her glimmering suit was a shocking pink chiffon scarf, and her shoes each sported a matching rose. She wore mammoth crystal earrings and a matching knuckle-sized ring.

“As long as I have love I can make it,” she sang; and then afterward she told the audience: “You’re a marvelous audience; I feel you. I’ve been around so many years, and I’ve loved you all that time.”

Someone screamed, “You still look great!”

“I don’t want to look like Mount Rushmore,” she replied, “just beautiful.”

Halfway through, she hopped up onto the piano for a drink. “I don’t want to break my image,” she croaked, excusing herself and offering a toast to the audience and to Palumbo.

She sang “How Insensitive” sitting on the center-stage steps; did a soft-shoe dance with several limber Rockette kicks to “The Trolley Song.” Her rendition of “What Now, My Love” was tender; then she smashed into “I’ll Go My Way by Myself.” At the end, mountains of roses were carried up onstage to her by Baily. “I’ll take anything I can get!” she said. The audience then sang “Happy Birthday” (it had been June 10 two weeks before). “God Bless!” she called out—and finally disappeared.

The next day, she gave a very “up” interview at her hotel, The Berkeley-Carteret, to The Asbury Park Press:

How do you like singing outdoors?

“I don’t mind it, but I don’t like it in the summer. The bugs, you know. They fly into my mouth.”

What do you do in that case?

“You park the bug like this.” She tucks her tongue into one cheek.

How’s your autobiography coming?

“It’s been quite a packed-in life. It will take years.”

Would you choose show business if you had your life to live over again?

“No! It’s a brutish business.”

Why do you attract a cult-like following?

“Maybe I’m some kind of female Billy Graham.”

Are you going swimming here?

“I’m afraid of water. I’m also afraid of flying,” she added.

How do you get around?

“Dogsled,” she joked.

Who are your favorite singers?

“Tony Bennett, Peggy Lee and Liza Minnelli!”

Your favorite food?

“Chicken, any way but fried, and ice cream cones. They never let me eat them at M.G.M.”

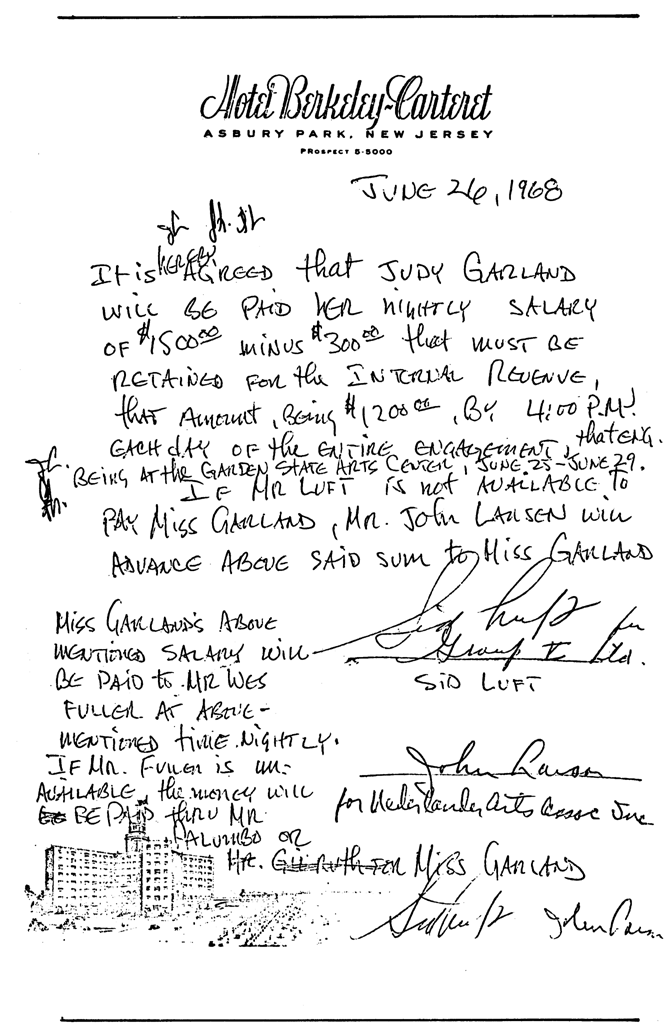

By night, a terrible storm had moved into the area. But the exterior turbulence was no more violent than the storm that was taking place in Judy’s hotel room. She had just discovered that on May 19, Luft had assigned her Group V Ltd. contract to Howard Harper and Leon J. Greenspan as security for a debt. She was appalled, furious; she refused to step out of the hotel until she had it on paper that she would receive money for her performance (her salary was to be $1,500 nightly, plus a percentage of the gate). Knowing she would not budge otherwise, Luft, using a piece of hotel stationery and crookedly printing the words, drew up a letter agreeing to pass over to her the amount of $1,200 (holding back $300 for federal taxes) each night before her performance.

Judy was, thereupon, given a $1,200 check and got up to go to the theater. Arriving late, during the height of the storm, she nonetheless managed to make it onstage, throwing her hands up to her face as she did, blinded by the lightning, deafened by the thunder.

“Well,” she said, gasping, “We’ll press on together.” But the storm grew louder and the rain fell more heavily. It was a losing battle; until the closing songs her performance lacked spirit, and she was painfully off-key. She told her audience that they had pulled her through. But on Thursday night even they did not appear to help.

She was suffering from an ulcerated sore on the sole of her foot. For Friday night’s performance she steeled herself with a massive dose of painkillers. These plus her usual pill intake caused her to be heavily drugged. Yet the performance almost came up to that of her opening night, and her audience, unaware of her problems, went wild. Then, on Saturday, arriving thirty-five minutes late and appearing sluggish (the drugs again having taken their toll), she sat on the stage, attempting to sing most of her repertoire from that position, and because of the severe pain in her foot that the drugs now seemed unable to mask, she had to be helped to her feet by Palumbo. At ten-fifty, after twenty-five minutes of pure endurance, she collapsed violently in a heap on the stage and was rushed to a hospital.

She had received no injuries in her fall, but her foot was found to be seriously infected. Fearing blood poisoning, she returned to New York City, where Dr. Udall Salmon placed her in the Le Roy Hospital.

In her dressing room the night before her collapse, wearing a long, frayed blue terrycloth robe and chain-smoking menthol cigarettes, she had confessed to reporters that what she would like most of all was to star in a Broadway musical. It had been more than idle daydreaming. Hal Prince was casting the musical Mame and Judy felt that she was perfect for the role. She embarked on a concentrated campaign and did, at least, seem to have Prince interested. For the next few months, winning the part was the most important thing to her. With the final realization that Angela Lansbury had the role (Miss Lansbury had supported her in The Harvey Girls), Judy then went on a campaign for the London Mame. Ginger Rogers won that role.

It is difficult to fathom how Judy thought she would have been able to sustain a strenuous musical like Mame night after night and for a long run; but it was easy enough to understand why she was attracted to the role. Mame, like herself, was a larger-than-life personality who raised a child under exceptional conditions. Mame was an aging eccentric with “pizazz” and at the same time a lovable, loving woman.

Not getting Mame was a deep disappointment—a personal rejection. Everything in Judy’s life, after that one shining night at the Garden State Arts Center, seemed to be falling apart. Her disillusionment with Luft was the most grievous thing she suffered. She now found that he had paid the hotel bill at the Berkeley-Carteret ($2,639.68—to cover the entire company for the five days) with a bad check, and the hotel was threatening to press charges. But the nagging question for Judy was what had happened to the money earned by the concert.

She was ill, and following her hospitalization at the Le Roy Hospital she went to Boston (borrowing money from a close friend) to seek help at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital. She and Luft had had a final and irrevocable fight, and he had returned to California. She was between men. Humiliating things had happened to her. She had been locked out of her New York hotel, and all her clothes had been impounded for nonpayment of the bill by Luft. Baily and the Garland Group had found her huddled pitifully alone in the lobby. "I’m Judy Garland and I don’t even have a clean bra to my name,” she had wept.

Joey had returned to California with Luft; Lorna enrolled in the New York Professional Children’s School (“I must have gone to about eight hundred schools,” Lorna says. “Every place we went, Joey and I had to be put in school. I never had any friends as a child.”) For the time of the last tour, Lorna and Joey had been with Judy. It had been a difficult, a bad time. What followed was worse.

Judy’s health was failing quickly, and she was in desperate straits. Lorna, sixteen at the time, had been exceptionally close to Judy. She was incredibly reminiscent of Judy as a youngster: all show-biz out front, but insecure, frightened and withdrawn in reality. And although it was Liza who appeared to resemble Judy the most, Lorna had the essence, the vulnerability, the injured look so indelibly identified with her mother. There is no question that in the spring of 1968 Lorna was suffering. Judy begged her to join her in Boston, but Lorna finally decided to fly to California to be with Luft and Joey.

“Mama called again,” Lorna says in a McCall’s interview, “I told her I just could not come to Boston. She didn’t understand. She kept asking ‘Why?’ I said I wanted a life of my own.”

And so at the same age as Liza had been when she left home, the youngster flew to the Coast. Judy was on a sinking ship without a captain, crew, or passengers. And she was very sick.

37If there is one allurement of the past, it is that it is the past. Judy was back in Peter Bent Brigham, old friend Kay Thompson supportive and close by; but it was as though her life had not been given notice that the curtain had fallen. With Luft three thousand miles away in California, Judy thought she might be able to cast him from her thoughts. But it was impossible. She was living in the most abject humiliation: penniless and dependent upon the kindness of friends; homeless—her furniture and personal possessions now impounded by an appalling assignment of the Group V Ltd. contract by Luft to Greenspan and Harper. Intense hostility bound her to Luft. Any dependence or sentiment was gone. There was no more lingering tenderness—no more “romance that would not die.” It was dead and even difficult to recall what had killed it. Yet burial was hopeless. She blamed Luft. How she blamed Luft! But even more, she blamed herself. Vanity made her feel an equal sinner; ego gave her a gnawing conscience.

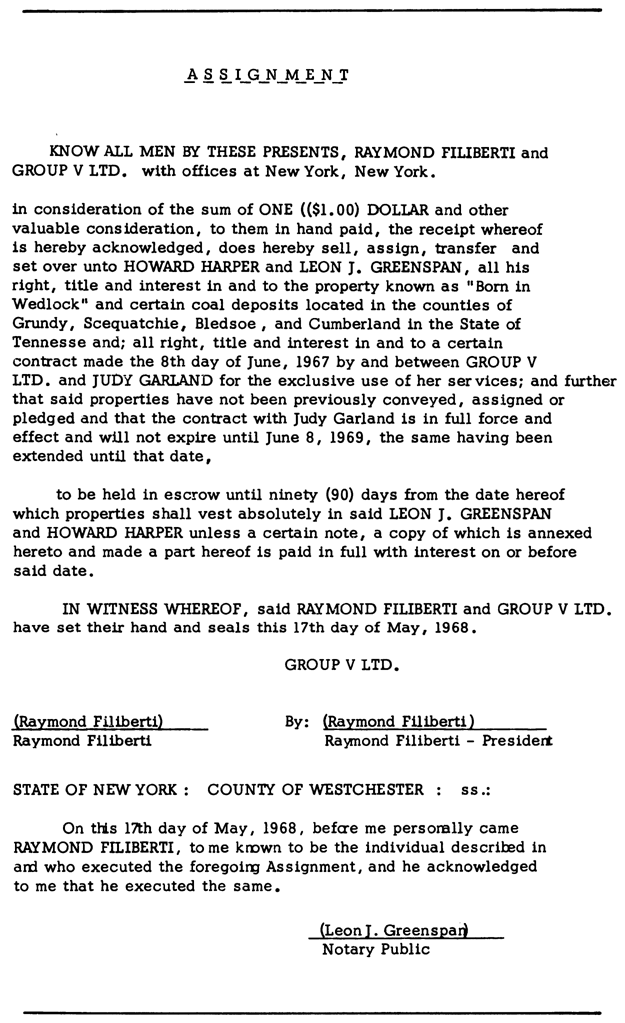

Pledged to appear at the Pavilion in Columbia, Maryland, on September 16 and 17; the Mosque Temple in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on September 30 and 31; and at the Springfield Music Fair in Springfield, Massachusetts, on October 2 and 7, she was now aware that if she did appear she would receive no remuneration. And that if she did not, she could be turned over like a piece of loan collateral (which she was) to Leon Greenspan and Howard Harper. For back in May, just previous to the Garden State Arts Center appearance, Luft and Raymond Filiberti had so desperately needed $18,750 that they had made an assignment of her contract to Harper and Greenspan.

It was to be one of the most controversial documents in her life. In it, Judy was “assigned,” “sold,” “transferred,” and “set over” to Harper and Greenspan for the fee of one dollar, along with an old film script called Born in Wedlock and “certain coal deposits located in the counties of Grundy, Scequatchie, Bledsoe, and Cumberland in the state of Tennessee.”

The specified ninety days had expired and Luft and Filiberti had not been able to repay the loan. On the twenty-eighth day of October in the Supreme Court of Westchester County, New York, Harper & Greenspan filed a Summons and Complaint against Group V Ltd. and Raymond Filiberti. Harper and Greenspan now wanted either their money or Judy Garland (also certain coal deposits in Grundy, Scequatchie, Bledsoe, and Cumberland, Tennessee, and the film script Born in Wedlock!). It is interesting that Leon Greenspan acted as his own notary public on the assignment, and were it not so thoroughly chilling to think of a human being parceled and sold along with some coal deposits and a script with an inane title, the situation might have an essence of hard-core black comedy.

It was a bleak and cold New York autumn when she returned from Boston after the Springfield engagement—broke, terrified, and alone. Yet it was curiously like other times she had come to New York by herself. There had been the time she had left Minnelli and MGM—that was when she had met Luft. And there had been the January when she had left Luft and signed with Fields and Begelman. Each of those times she had found solace in walking the city streets alone, trying to find some true corner of her own identity. However, it was not as easy to walk now. She was weak. There were physical things happening to her that alarmed her. She was not steady on her feet. Her vision had grown dimmer. The nightmares and sleeplessness had returned. And though she was finally so painfully thin that she should have been able to eat what she wanted (she stopped at the carts of street venders and bought hot dogs she could not eat), solid food sometimes gagged her, and when she was able to eat it she would suffer excruciating stomach pains, accompanied by such extreme constipation that she found herself waking up on the floor of the hotel bathroom not knowing how long she had been lying there unconscious. Nor was she ever sure she would not come back to the hotel to find her belongings impounded. One possession—a mink coat—she wore constantly, loving the elegant feel of it. She had posed in it for Richard Avedon for an advertisement for Black Glama Mink, and afterward it had been presented to her.

She was fighting a game battle for the survival of her spirit and therefore tried to concentrate on those things that would “get her through.” She read the Bible, learned long passages of it by heart; memorized some of Shakespeare’s sonnets; and tried to “get straight” all she could remember about her father. Frank Gumm, in fact, was occupying much of her thoughts. She related him to a feeling of gaiety and hope. In retrospect, it seemed to her he was the only man who had truly loved her.

Most family photographs had been lost in the impounding of her personal possessions through the years and by the gypsylike existence she had lived, and so she could not find a picture of him. For the first time in a number of years, she contacted members of the family. No one had a picture of Frank. It came to her as a shocking revelation that her only memory of her father was as a man who had looked younger than she now looked. He had been a laughing, fun-loving Irishman with a full head of dark hair and a lithe, graceful body. His image, however, seemed confused with other images: those of Tyrone Power, for one; Mark Herron; and now Mickey Deans.

Reverie kept bringing Deans to her mind. In the few times she had been with him she had been able to forget her troubles. His enthusiasm and laughter had been infectious. There had been a rapport. They had liked the same things, had had the same offbeat sense of humor, the same ability to be silly without embarrassment. He was thirty-four and that was young, for she was forty-six. But her father had died young, and she could recall how small and protected and female he had made her feel when he took her that first day to MGM; how he had walked right in and faced all those big-time executives; how he had that time defied Ethel; how he had looked at her in her dirty slacks and no makeup with dancing eyes that said, “What do they know? I think you’re beautiful”—how he had, indeed, made her feel beautiful.

She had spoken to Deans from Boston. She rang him again on her return to New York, and they began to see each other. The last man in her life had now appeared. Being Judy, she was to believe and to publicly state that he was the true love of her life.

Deans was born Michael DeVinko in Garfield, New Jersey, on September 24, 1934, the youngest of three children in a Greek-American family. His father was a textile worker who had a hard time supporting the family. Deans hated the smalltime, lower-class life in Garfield. His only thought from the time he hit his teens was to leave it. Good-looking and with an outgoing personality, he was certain he could make it in show business if he had the opportunity.

When he was fourteen he took the $35 he had earned working in an appliance store near the small DeVinko house and bought an upright piano with fourteen broken keys. His father forbade him to bring it into the house, but his sister spoke up in his defense. All the living-room furniture had to be crowded together to make room for it. The piano was impossible to play in the condition it was in. Deans, therefore, went to a professional tuner and talked him into allowing him to apprentice until he could learn how to fix and tune the old upright himself, continuing to work afternoons and weekends to pay for classical lessons and for a television set. He deemed the set an important addition to his training, studying the performers on the small screen as assiduously as he had observed the piano tuner. Ethel had done much the same thing in that old movie house in Grand Rapids.

By sixteen he felt he could make it on his own in the jazz world, left home, and began a long line of small-time club “gigs”—Club Lee in Fort Lee, New Jersey; the Jungle Club in Union City; The Tender Trap in Fairview. It was a nomadic, nighttime world. He was young and ambitious and tough enough not to care what was happening around him or to him if it meant steamrolling himself to his final goal: a club date in New York. People moved into and out of his life, but he had learned how to chop things off, how to keep his eye leveled on the main goal.

Then came Jilly’s. He got his first close-up view of the “big-timers.” They came while he played and talked through his sets and never really saw him through the dense clouds of cigarette smoke. He knew club playing was not what he wanted. He had to be out front, where the action was—where the stars were.

From Jilly’s he went to the Tenement in New York, then traveled out to Harold’s Club in Reno, Nevada, hating what he was doing; feeling servile (“Play ‘Melancholy Baby’”), rootless, losing back his pay to the casinos where he was the “bar pianist.” The years passed. He wasn’t sure how he was going to do it, but he was determined to make a pitch for the “big time.”

He had heard about Judy Garland, seen a concert of hers in Newark, New Jersey; but her music had not reached him. He was still very much a part of the jazz world. When he thought about her, it was in neons. He admired her star status and understood her use of pills. He took them himself—“ups” to keep him going, “downs” to sleep, both together for a buzz; but he could do without them, too.

No photographs of him in the late sixties do him justice. They are static, and Deans never was. Not handsome in the general sense, he had incredible charm, a disarming boyishness for one so worldly, a strange symphysis of audacity, youth, and humility. Slim and vital, he stood in attitudes and gestured extravagantly. His eyes would dart, a smile break open his face; his laugh would roll out unrestrained, uninhibited. He paced a lot, drummed his fingers on static surfaces, doodled whenever he had pencil and paper, and used his hands whenever he spoke (language coming from him rat-a-tat-tat; ideas, words shot out before being carefully aimed). His voice was deep-timbred, words were mumbled or jumbled, but the flow did not stop. Occasionally he would sing at the piano in an untrained voice, surprising his audience with an innate and creative sense of phrasing. He was natively intelligent, alarmingly sensitive, deeply emotional—the emotion playing hide-and-seek with the laughter revealed in his dark, rather myopic eyes. He had all the appearance of a downhill racer trying with all his lifetime experience to avoid a dangerous and sudden stop. As he reminded Judy so strongly of Frank Gumm, perhaps one can visualize through Deans a clearer picture of Judy’s father fantasy.

When Sybil Burton opened Arthur, her idea was to create a club where performers, the famous, and the infamous would have a sense of “grooving.” The decision was made to use young actors and musicians who wanted to be seen—as waiters.

Deans started as a captain and then became Night Manager. He liked the role, and found being on social terms with the star clientele exciting.

If Judy had blocked out the “pill meeting,” Deans had not. What had remained in his mind from that night at Judy’s hotel was Lorna. “Are you all right here alone with your mother?” he recalls asking her. “I’m fine,” she replied grimly. There had been something painful in her face, he says; something old, yet still vulnerable in her straight and honest returning glance. It had made him feel sick, and he was glad when he reached the fresh air. He knew without questioning further that there had been many other semidark, middle-of-the-night strangers with pills; that the youngster had protected and cared for a “stoned-out” mother many, many times, knew the symptoms, helped in finding the cure. And there was her “wise mother” protection of the little boy. He was aware that Lorna had been playing this role from the age of no more than eight or nine. For all those years since then, Lorna had been a firsthand “attender” to her mother’s deep needs.

After that evening when they had talked until four in the morning at Arthur, Judy had sent Deans tickets to see her at the Palace. He had attended; joked with Bobby Cole, who was a friend of his; but had not gone backstage to see Judy. She had come into the club a few times. Each time he had sat with her. Until her return from Boston they had not spent any time privately together. He was still involved in another relationship, but now she began to frequent the club, and Judy would say, as she did in her concerts, “I don’t ever want to go home, do you?” They’d have breakfast together, would go shopping at five in the morning, and Judy, tiny as she was, would sit in the basket and Deans would push her around the all-night market, neither of them caring what anyone else thought.

Judy began to feel very secure. She saw Deans mostly at Arthur while he was at work and in command, greeting customers, handling crises, attending to her needs. She felt he was strong, and she liked the feeling of power he exuded. He did nothing to control her pill intake, but he did get her to eat, to sleep, to push aside terror. She was depending upon him a lot; she found he was a good musician, knew about lighting, had good taste in clothes, was tough, ambitious and audacious, and possessed the natural instincts of an entrepreneur. She told someone there was a bit of Mike Todd about him. There was, as well, a bit of Sid Luft.

The phenomenon of Arthur was beginning to run its course. Everyone with an interest in the club began to blame the others, but the truth was that the parade had simply passed it by. The party was over, and yet all of Deans’s efforts went into an attempt to keep it going. At the same time, he was seeing more and more of Judy; becoming more and more enmeshed in her world, her life; trying to help her at least get back on her feet. He was with her when she appeared on the Merv GrifEn show (as was Margaret Hamilton, the witch in Oz and her old “friend”), the Johnny Carson show as well. He felt she could come back, could even make it financially big again. He was enough of a musician to also realize her voice and endurance were shaky, but astute enough to be aware that the ring of stardom to her name could allow her to cash in on side benefits. It was these side benefits—ventures in which her name would sell a product—that he believed would bring her back into the big chips. He had an idea for miniaturized cinemas to be called The Judy Garland Theaters: that was a first step.

She signed a new contract for recording and was offered a month’s engagement at the first-class theater restaurant The Talk of the Town in London. She had told him nothing about the Group V Ltd. assignment, and so he convinced her she should take it, but Luft had her musical arrangements and refused to release them without a sizable figure’s being paid for them. Deans told her to “tell Luft to fuck it! I’ll get you new arrangements.”

It led to her hopefully suggesting he accompany her to London and help her organize the show. They were in Arthur. It was four in the morning. The place reeked of stale liquor and burnt-out cigarettes. It was time to close up, go home; but neither really had a home to go to—for Judy was staying at a hotel, and Deans, up until that time, still shared an apartment, not having yet been able to break off his long-standing old relationship.

“I suppose it would make more sense if we were married,” Deans says he told her. It was a curious proposal.

“You better not be kidding,” he reports Judy replied.

“I’m not kidding,” Deans assured her, and on December 28, 1968, they left New York together on a London-bound flight, not knowing exactly what they had to do to get married, since Deans was a Catholic and Judy was divorced from Luft and not sure of her marital status with Mark Herron. The only thing Judy was sure of was that she felt alive and loved and hopeful with Deans. He helped her to forget the bad things and remember the good. She clung desperately to his arm as they climbed aboard their flight. They traveled first-class, VIP. Deans had arranged it. He held her in his arms as the plane lifted off the ground. It was the first time in her life that she had not been afraid of flying.