People like to say that nature is complicated and becoming even more complicated. A lot has been said about diversity, complexity, unpredictability in nature, and more recently about the law of physics that accounts for all such observations. In this chapter, I distill this body of knowledge to just three ideas:

Live and dead trees on Kapinga Island of the Busanga Plains, Zambia (Hot air balloon photo at sunrise: Adrian Bejan). Under this forest, the soil is a vast and tightly connected hierarchical vasculature of fungi that transports to the live trees the nutrients from the fallen trees, leaves, and fruit. The hierarchy of the tree society is visible above ground: few large thrive together with many small. Like a country, the tree society is held together by the ground, which is a live flow system vascularized with a hierarchy of diverse flows of water, nutrients, and animal life, constantly morphing in freedom

Many other images go unnoticed, as if taken for granted. One class is the round cross sections of ducts, and they cover the board from blood vessels, pulmonary airways, and earth worm galleries to the “pipes” carved by rainwater in wet soil and the hill slopes of the smallest rivulets of the river basin. Technologies of many kinds employ round ducts, and for a good reason: they offer greater access to what flows, greater than in the absence of round cross sections.

Less known are the rhythms of nature, the designs that represent organization in time, not in space. In most places, the flows that sweep areas and volumes flow in two distinct ways. In the river basin, the water first flows as seepage in the hill slopes (by diffusion, called Darcy flow), and later as streams in river channels. This combination is the physics of what others call “anomalous diffusion”. The first way is slow and short distance, while the second is fast and long distance. Mysteriously, it seems, the water spends roughly the same time by flowing slowly (as seepage) and by flowing fast (as channel flow). The equality of times is the rhythm, and it is predictable from physics.

Oxygen reaches the lung volume thanks to the same design of two flow mechanisms. The short and slow is the diffusion across the vascular tissue of the alveoli. The long and fast is the flow through the pulmonary tubes. Diffusion and tube flow take the same time, which is the time of inhalation. Carbon dioxide is evacuated in the opposite direction, from a volume (the thorax) to a point (the nose). The same two-way combination facilitates the flow of carbon dioxide, first by diffusion across alveoli walls, and later by tube flow at larger dimensions. Diffusion time is the same as tube flow time. Even more intriguing is the fact that the point-volume flow (inhaling) takes the same time as the volume-point flow (exhaling). The flow direction (in and out, inhaling vs. exhaling) is not the idea, the rhythm is.

The same temporal design governs the flow of nutrients via blood circulation. Diffusion across the walls of the smallest blood vessels (the capillaries) is the short and slow way to flow. Stream flow along vessels larger than the capillaries is the long and fast way. The diffusion time is the same as the duct flow time. This is true for both directions of flow, in the arterial system (from lungs to whole body) and in the venous system (from body to lungs). In both directions, the flow is a design consisting of two tree flows, a volume-point tree connected to a point-volume tree where the point is unique (the heart), and the volume alternates between body and lungs. The time scale (the heartbeat) is the same for both directions of blood flow.

Rhythm and tree design govern the flow of water on land. The area-point flow of the river basin is followed by the point-area flow of the delta. The point in this image is one: the entrance to the delta. I grew up at such a point, on the Danube. Vegetation design is the coupling of two trees, and the base of the trunk is the connection. The root system is the tree that carries water from the wet ground (a volume) to the base of the trunk (a point). The tree above ground carries the same stream of water upward, from the base of the trunk to the volume that contains the canopy and the dry air that blows through the canopy.

Diversity is part of the evolutionary design phenomenon. To appreciate its origin, think of how we all move through the seemingly rigid infrastructure of the city. We move with freedom. We make free choices all the time. Crowds flow as trees, from area to point and from point to area. In the early morning the crowd of commuters converges on the train station and the airport. It does so with hierarchy, with denser columns of people and automobiles on the larger and straighter streets that reach their point-size destinations. The canopy of this morning tree of human flow is the whole city area. In the evening, the same crowd flows in the opposite direction, from the point to the area (the city). In the morning, the city exhales people, and in the evening it inhales.

How the ski slope “exhales” its population: hierarchical basin of skiers flowing down the side of a mountain covered with fresh snow powder (Photo: Rick Frothingham 2011; with permission)

Bigger flow architectures (river basins, lungs) are more complex, yet, their complexity is not changing; it is certainly not increasing in time, and not getting out of hand [1].

All forms of animal locomotion (swim, run, flight) constitute a precise rhythm in which the frequency of body fluctuations (fishtailing, leg stride, wings flapping) is lower when the body is bigger. The speeds of bigger animals and aircraft are greater than those of smaller movers. Bigger movers can lift bigger weights, and have greater metabolic rates [2, 3].

The bigger movers also exhibit longer life spans and longer distances traveled during lifetime. This holds true for all movers—animals, vehicles, rivers, winds, and oceanic currents [4].

All flows that spread from one point to an area or volume (floods, snowflakes, human bodies, populations, plagues, science, inventions, political ideas) have territories that increase in time in S-curve fashion, slow–fast–slow. All flows that are collected from an area (or volume) have territories with S-curve histories, past and future. Examples are the evolving architectures of oil wells and mine galleries (tree-shaped, underground), each morphing and covering a territory that is expanding slow–fast–slow [5].

Ancient pyramids and piles of firewood constructed by humans on all continents have the same shape. They are triangular when viewed in profile, with a shape that is as tall as it is wide at the base [6, 7].

The earth’s climate is stable, in a state of stasis with three distinct temperature zones, each with its own cellular currents and global circulation. This is the main design, with the earth as the intermediary node in the one-way flow of the solar heat current that the earth intercepts and then rejects to the cold sky. This design is predictable [8]. Superimposed on this design are small climate changes, also predictable [9], which are due to changes in the radiative properties of the atmospheric shell.

Turbulent eddies (whirls) are born when the stream is thick and fast enough such that the rolling time of the eddy is shorter than the time needed by shear (viscous diffusion) to penetrate across the stream or the eddy. This rhythm is the phenomenon of turbulence, and it is why (contrary to established view) the phenomenon of turbulence is no longer an enigma since 1980 [10–12]. The origin of turbulence, which constitutes a constructal theory, should not be confused with computer simulations of highly complex (high Reynolds number) turbulent flows, such as weather prognosis, which are empirical, based on measurements and then modeling. Improving weather modeling should not be confused with predicting when and what turbulence should happen in a perfectly smooth (undisturbed) flow.

For a finite size flow system (not infinitesimal, one particle, or subparticle) to persist in time (to live) it must evolve with freedom such that it provides easier and greater access to what flows.

In this statement, finite size means not infinitesimal, not one particle, and not one subparticle. It means a whole. Configuration (design, drawing) is macroscopic. Furthermore, to evolve and to persist in time as a flow system with configuration is the physics definition of to be alive. The opposite of that (nothing moves, nothing morphs, nothing changes) is the physics definition known as “dead state” in thermodynamics [13].

I wrote the constructal law when I knew a lot less about its implications. Now I see that the words “evolve, freedom, access” mean one thing. We all know what that thing is when we don’t have it: freedom. That thing is what has been missing in physics.

All the dissimilar phenomena discussed above have been predicted by many authors by using the constructal law. So far, 12 Constructal-Law Conferences have been held all over the world, three sponsored by the U. S. National Science Foundation and one by The Franklin Institute.

So, that’s the first idea. Evolution of design is a universal, unifying phenomenon of nature, and it is predictable based on its own law of physics.

The second idea is that all flow systems happen because they are driven by power. They flow and move because they are pushed, pulled, pumped, sucked, twisted, straightened, and shaped because of power. Power means work done per unit time on the system of interest. The work done is the product  , where the force is applied by the environment on the system and the displacement is the travel of the point of application of the force. The travel is relative to the frame of reference of the environment.

, where the force is applied by the environment on the system and the displacement is the travel of the point of application of the force. The travel is relative to the frame of reference of the environment.

In sum, work entails movement, deformation, morphing, and change. The spent power is the cause of movement and change per unit time. The spent power is what drives the tape of evolution, the movie of design change over time.

The power comes from engines of all kinds and sizes. All engines happen naturally, the geophysical, the animal, and the human made. Most engines are not made by humans. Like the wheel, the engine is a natural flow architecture, not a human invention that does not exist outside the human sphere. The wheels of the biggest engines on earth are the currents of atmospheric and oceanic circulation. The wheels of a much smaller engine are under the mouse: two spokes (two legs) for each wheel, one wheel in front, and one in the rear.

The environment opposes the movement of the flow system. It resists being pushed out of the way. Consequently, the power that causes the movement is dissipated instantly into heat, which is transferred to the ambient. The relative movement between system and environment acts like the brake on a vehicle.

In thermodynamics, brakes are known more generally as purely dissipative systems. In the simplest model, a purely dissipative system (or a brake) is a closed system that receives work and rejects heat to the environment (“closed” means that mass flows do not cross the system–environment boundary; closed does not mean “isolated”). The system is in steady state, which means that its system properties (volume, pressure, temperature, energy, entropy) do not change in time. The brake system converts its work input fully into heat output. All brakes happen naturally; only a tiny number are made by humans, for vehicles.

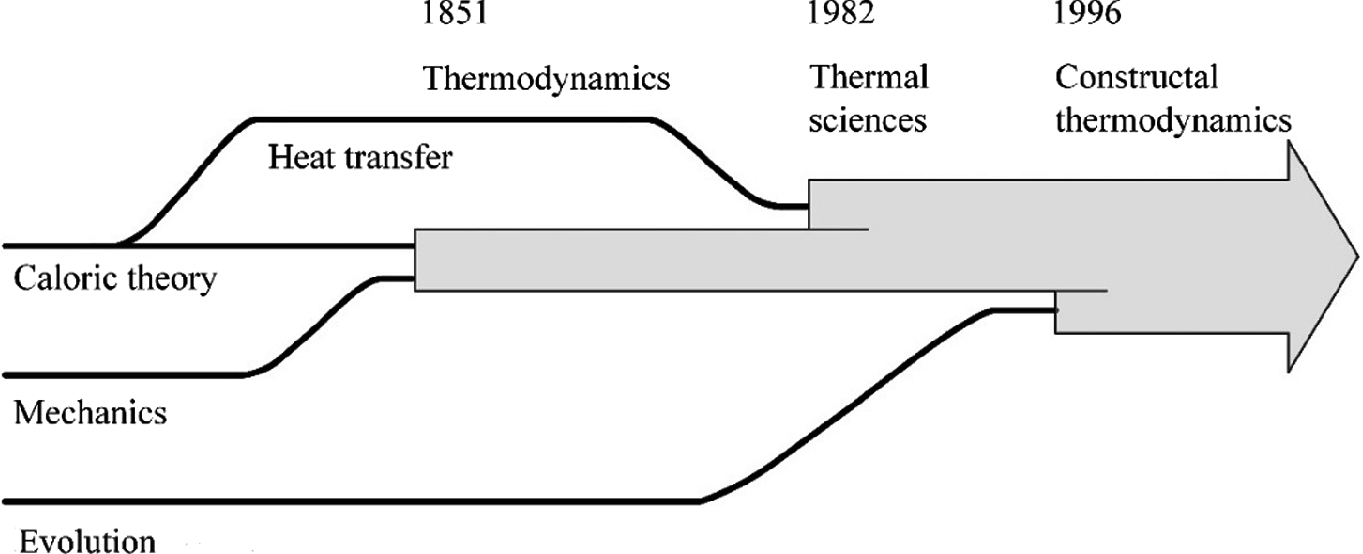

The evolution and spreading of thermodynamics during the past two centuries

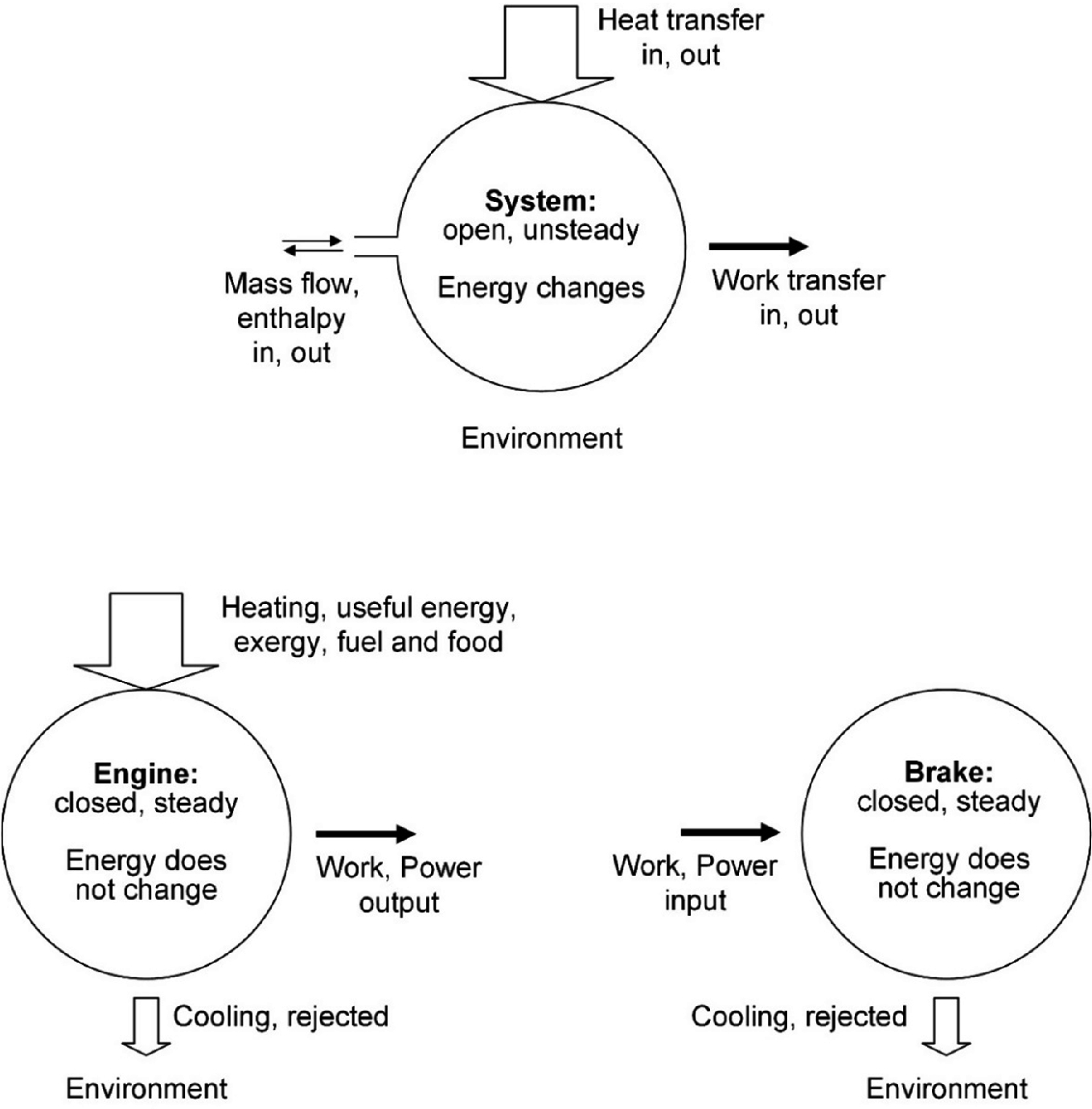

Nature is in the eye of the beholder: it consists of just two systems, the system selected by the observer for analysis and discussion, and the rest, which is called the environment or the surroundings, also selected by the observer. Separating the two parts is the system boundary, which is chosen by the observer. Top: an open system can experience mass flow, heat transfer, and work transfer across its boundary. A closed system cannot experience mass flow, because its boundary is impermeable. Bottom: two classes of closed systems in steady state (not changing in time): engines and purely dissipative systems (brakes)

The second law is a concise summary of innumerable observations of the phenomenon of irreversibility in nature. Irreversibility means one-way flow, like the water over the dam, or under the bridge. Any stream (fluid, heat, rock avalanche) flows by itself in one direction, from high to low. Water flows in a pipe from high pressure to low pressure. Heat flows across an insulation from the high-temperature side to the low-temperature side. Rocks fall from high altitude to low altitude. Never the other way around.

The keywords in invoking the second law correctly are “irreversibility” and “by itself.” Why, because a stream can be forced to flow the other way, from low to high. Water in the same pipe can flow from low pressure to high pressure if a pump is inserted between the low and the high, provided that power flows from the environment to the pump in order to push the water in the unnatural flow direction. Similarly, heat flows from low temperature (the cold zone) to high temperature (the room) in a refrigerator (the system), provided that power flows from the environment into the system in order to drive the compressor and “elevate” the heat current against its natural falling tendency.

No process is possible whose sole result is the transfer of heat from a body of lower temperature to a body of higher temperature (Clausius).

Spontaneously, heat cannot flow from cold regions to hot regions without external work being performed on the system (Kelvin).

The second law is a most general statement, which says nothing about terms such as entropy, disorder, classical, and thermostatics. It is a statement of common sense, not jargon. It is not a mathematical formula. More recent reformulations of the second law in terms of disorder or entropy death are also correct but they hold for special and significantly narrower realms. The most general statement (from Clausius and Kelvin above) holds for “any system,” and for the most universal manifestation of the second law phenomenon, which is the natural phenomenon of irreversibility.

Caution: Today, it is fashionable to assign revered labels (thermodynamics, entropy) to new concepts, and as a consequence, there are many “entropies” in circulation [15]. So, when you hear about the “thermodynamics” of this or that, ask that speaker to define his or her “system”, and to show you the heating (thermē) and the power (dynamis) received or delivered by that particular system. Ask the speaker to define the “entropy” to which he or she refers. Fortunately, you do not have to wait forever for an answer, because the proper exposition of thermodynamics terminology and laws is widely available, for example, in Refs. [13, 14].

Entropy change (not “entropy”) is a mathematical quantity invented by Clausius in order to express mathematically the irreversibility of any process (any change of state) experienced by any system. In entropy representation, the second law is an inequality, and the strength of the inequality sign is a measure of how irreversible (dissipative, lossy, imperfect) the process is. Here is a brief introduction to the terms in use:

The mathematical definition of entropy change is made with reference to a closed system that experiences a reversible process (from state 1 to state 2) during which it receives the infinitesimal heat transfer δQ [J] instantaneously from an environment of thermodynamic temperature T [K]. By convention, δQ is positive when entering the system, as in the functioning of a steam engine. The temperature of the system boundary spot crossed by δQ is equal to the same T, because during reversible heating or cooling there are no temperature differences and gradients anywhere. As the boundary temperature T changes during the process, so does the environment temperature. The definition of the change in the entropy of the system is the formula  , where S is a system property (a function of state, like volume and energy) and S2 and S1 are the inventories (the values) of entropy at states 1 and 2. The infinitesimal δQ/T is the infinitesimal entropy transfer that accompanies the infinitesimal heat transfer δQ at the boundary point of temperature T. That is the new idea, heat transfer is accompanied by entropy transfer.

, where S is a system property (a function of state, like volume and energy) and S2 and S1 are the inventories (the values) of entropy at states 1 and 2. The infinitesimal δQ/T is the infinitesimal entropy transfer that accompanies the infinitesimal heat transfer δQ at the boundary point of temperature T. That is the new idea, heat transfer is accompanied by entropy transfer.

The second law must not be confused with the above definition, which is the definition of the property called entropy. The mathematical statement of the second law in terms of entropy is an inequality, and the inequality sign means “one way,” or irreversibility. The simplest such statement is the one that holds for any closed system that executes any process 1–2, namely,  . In this statement, T continues to represent the temperature of the boundary spot crossed by δQ, regardless of the presence or absence of temperature gradients.

. In this statement, T continues to represent the temperature of the boundary spot crossed by δQ, regardless of the presence or absence of temperature gradients.

One way to state the second law in words is to say that for any process executed by a closed system, the entropy change (S2 − S1, the change in the state function called entropy) cannot be smaller than the entropy transfer into the system,  . More general versions of the second law inequality of the preceding paragraph hold for more general versions of system definition, for example, for open (not closed) systems operating in general, time-dependent fashion [14].

. More general versions of the second law inequality of the preceding paragraph hold for more general versions of system definition, for example, for open (not closed) systems operating in general, time-dependent fashion [14].

Comparing the two mathematical statements in the preceding three paragraphs we see the difference between a reversible process 1–2, and a general (called irreversible) process 1–2. It means that in the limit where the general process is reversible, the inequality sign  reduces to the equal sign. This is why it is correct to view the inequality sign as a measure of the severity of irreversibility (or the departure from reversibility) of the process 1–2. Irreversibility means a flow that proceeds one way, from high to low. The inequality sign in the mathematical second law is a measure of the severity of the fall from high to low.

reduces to the equal sign. This is why it is correct to view the inequality sign as a measure of the severity of irreversibility (or the departure from reversibility) of the process 1–2. Irreversibility means a flow that proceeds one way, from high to low. The inequality sign in the mathematical second law is a measure of the severity of the fall from high to low.

During the past 150 years, the mathematics based on the S formulation of the second law (and on the definition of entropy change S2 − S1) has become the discipline of thermodynamics that underpins virtually every single calculation, design, and technology that powered humanity in the modern and contemporary eras. None of this has anything to do with design, organization, freedom, and evolution in nature. The evolution phenomenon is distinct from the irreversibility phenomenon, which is why the constructal law is distinct from the second law (Fig. 1.3).

All processes in nature are irreversible. In the theoretical limit imagined by the original founder (Sadi Carnot 1824), the irreversibility is negligible, the inequality sign becomes the equal sign, the process is said to be reversible, and the second law is an equation, not an inequality. Unlike the second law, the first law is always an equation, regardless of the irreversibility or reversibility of the process. In this book, it is not necessary to use such mathematics. It is in fact advisable to tell the story without mathematics and, especially, without using the word entropy. Figure 1.4 is a graphic summary of the thermodynamics discipline of the first law and the second law. The system is any imaginable region in space or amount of matter. This is why it is drawn empty, like a black box. The two laws apply to any system that would reside inside the box. This utmost generality is also the limitation of the two laws. Why, because the systems of nature are not black boxes. They have configurations endowed with freedom to change into new configurations. This is why evolution has become part of thermodynamics (Fig. 1.3).

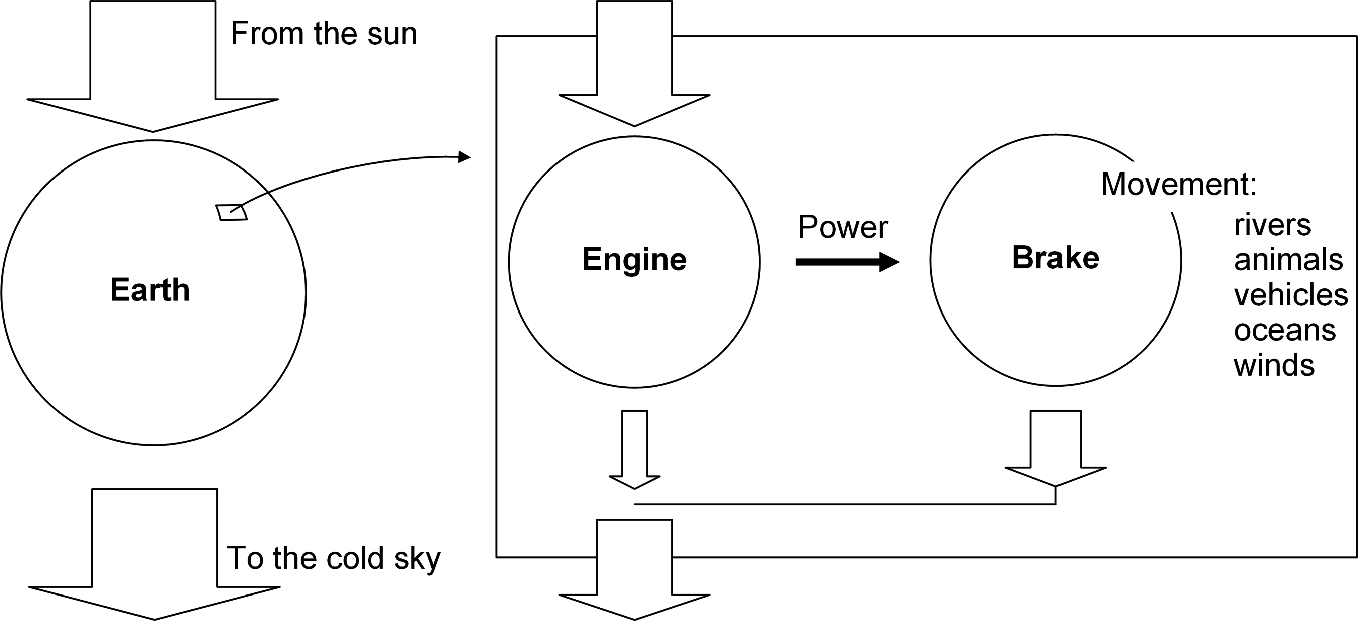

Nature is a rich tapestry of superimposed “engine + brake” systems, all flowing, moving, churning with freedom, morphing and evolving. This live tapestry converts into heat (rejected to the ambient) all the power produced by all the engines that drive all the movement. Because every engine converts its heat input only partially into power and rejects the difference as heat to the ambient, and because the power is itself dissipated into rejected heat, it follows that the heat input (originally, from the sun) to all the engines is rejected completely to the environment. For the earth-size engines mentioned previously, the environment is the cold sky.

Evolution enhances the mixing of the earth sphere. Inanimate and animate flow systems evolve in the same direction, to flow more easily and farther, by using and carving their environment, and carrying it with them.

The flowing tapestry of engines and brakes that mix and turn over the earth spheres, atmo, hydro, bio, and human

The bottom line is that the passing of the solar heat current “through earth” has the effect of constantly mixing the earth sphere, because of the running engine that drives the brakes that dissipate its power. Evolution is constantly improving the engine + brake design of earth so that the mixing is enhanced naturally, relentlessly. The live world is an immensely, highly diverse population of “vehicles,” animal, geophysical, and human made, constantly moving and flowing as engine + brake systems. This tandem is the physics of what others called more recently “active matter” and “live matter”.

So, that’s the second idea. The sun heats the earth with a finite heat current, which is rejected 100 percent to the rest of the universe, like all the heat currents emanating from the sun. The earth is special, because it has properties that give birth to wheels of engines and brakes. Thanks to the freely evolving design of the engines + brakes tapestry, the sun drives the mixing and turning over of the earth’s surface. This is why life happened on earth, and how it may be found on other planets.

The third idea is that humans are like everything else that moves and morphs on earth. We are driven by power from our engines (human body, metabolism and muscle power, domesticated animals, and vehicles), the engines consume fuel and food, and our movement dissipates the power completely. This flowing architecture evolves with freedom in a discernible time direction, which is captured by the constructal law on page 5. Our movement (our life) reshapes the earth in a progressively greater and more effective way over time, like the rivers and the animals.

Humans are not naked bodies. Each of us is much bigger and more powerful because of the contrivances (add-ons, artifacts, the artificial) that are attached to us. We are encapsulated in our ingenuity, which is represented physically by our artifacts. We carry them with us, and they carry us with them.

Contrivances enhance the effect of human effort, from the shirt, knife and fork to the rope, pulley, and the automobile. The ancient Greek word for contrivance is mihani, which is the origin of modern concepts such as machine, mechanics, mechanical, mechano, mechanisms, and machinations. The word “machine” covers all the imaginable artifacts that empower humans. The “mechano” realm illustrates the meaning and direction of the constructal law, as summarized in the title of my 2000 book “Shape and Structure, from Engineering (i.e., mechano) to Nature” [2]. This is the physics behind new terms such as “mechanobiology” and “technobiology”.

We are the “human and machine species”. Each of us is a human and machine specimen that evolves during his or her lifetime. The machine part evolves every day through technology, commerce, science, language, writing, listening, recording, education, and artificial intelligence.

That’s the third idea, and it emphasizes the pivotal role of all three. The physics of freedom and evolution is about us. Freedom is access to power. This is why this new science is absolutely essential.