In Houghton County, just north of the cities of Houghton and Hancock, lies the high country — a gathering of communities nestled atop the spine of the Keweenaw, in an area prone to heavy snowfalls. Today, Calumet Township includes the villages of Calumet and Laurium, plus the surrounding communities of Osceola, Centennial Heights, and Kearsarge. These days, no one would consider Calumet to be a bustling metropolis, but in the heyday of copper mining, Calumet was just such a place.

By the 1860s, Calumet had already become well established as a copper mining community, and in 1866 a new road was under construction that would connect Calumet Township with Hancock to the south. The operations of the Calumet & Hecla Mining Company, often known simply as C&H, served as the impetus for much of the development in the Calumet area. Back in those days, however, Calumet was known as Red Jacket — and the village now called Laurium was known as Calumet. This makes the history of the region a bit confusing at times, especially since Red Jacket was often known colloquially as Calumet. The two villages of Red Jacket and Calumet (Laurium) existed side-by-side, much as they do today. When driving up M-26 from Lake Linden, it's hard to distinguish the modern villages of Laurium and Calumet, as their boundaries blend together.

Back in the days when Calumet was Red Jacket and Laurium was Calumet, the township that encompassed both villages boasted an ethnically diverse population. Finnish, Cornish, Irish, and Italian immigrants are most famous today for the part they played in Calumet's history, but Houghton County also became home to immigrants of Croatian, Chinese, French Canadian, Polish, and Slovenian descent. By 1870, Calumet Township supported 3,182 residents, with immigrants making up over 60% of the population. At this time, the village of Calumet (now Laurium) had yet to be born.

Copper played once served as the keystone of Calumet's economy. This monument preserves a chunk of float copper weighing in at 9,392 pounds, which was dug up a few miles outside the village back in 1970. Photo by Lisa A. Shiel.

The year 1875 marked a milestone in the township's history, as Red Jacket became an incorporated village. By this time, the township had five schools and library with over five hundred books, making it the largest library in the Keweenaw. The township's population continued to grow at a brisk pace, thanks in large part to C&H and other local mining operations. As of 1880, the population had surged to 8,299 in the township as a whole, with 2,140 of those residents in Red Jacket. Copper mining had reached its boom, and things would only get better, economically speaking, for the next three decades. Mining was hard and dangerous work, but copper made the Keweenaw. Without it, Calumet might never have reached the heights it achieved during the days of C&H.

The 1880s found the township expanding again and again. A town hall was built in 1886, and in 1889 the village of Calumet emerged southeast of Red Jacket. Six years later, the new village underwent a name change to officially become Laurium, the name that has endured since. Meanwhile, Red Jacket had grown to such size and prosperity that a Marquette newspaper dubbed it "the most cosmopolitan town in America." Since many of Red Jacket's businesses boasted electric lights and other modern amenities, the moniker seems well deserved. By 1898, the village of Red Jacket had swelled to over 4,000 residents, with another 30,000 in the communities that surrounded it. Calumet Township had become one of the largest metropolises in the state. Perhaps this explains why a there's a long-standing myth that Calumet was once in the running for the title of state capital. Although no one has found proof to support the state capital rumor, it does stand as further evidence of what a thriving community Calumet Township had become.

During the copper boom, the Keweenaw — and especially Calumet Township — developed into a flourishing economy. In 1899, C&H reported stock dividends of $10 million. Taking inflation into account, in 2014 those dividends would equate to approximately $278 million. That's an impressive profit for any company in today's world of multinational corporations. Back in 1899, it was staggering, particularly considering that C&H was one company that operated solely in the Keweenaw and mined nothing but copper. No wonder immigrants flooded to the Copper Country in pursuit of their own American dreams. Mining may have been thankless work that claimed many lives, and the Keweenaw's climate and remoteness may have pushed pioneers to the breaking point and beyond, but the region certainly offered bountiful opportunities for those brave enough to take up the challenge. The individuals who owned and ran the mining operations saw the most profit, naturally, and a growing sense of unrest would lead to a defining moment in Calumet's history.

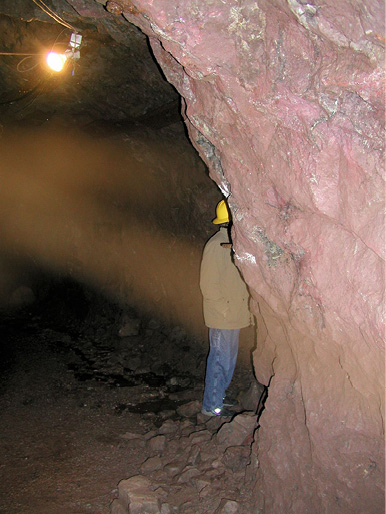

The interior of the Quincy Mine, now a tourist destination but once a powerhouse of copper production. The mine sits between Hancock and Calumet. Photo by Lisa A. Shiel.

In the meantime, however, the township kept on growing. The turn of the century saw a population of some 45,000 residents living within three miles of Red Jacket and Laurium. Two years into the new century, the township welcomed trolley service, thanks to the Houghton County Traction Company and its new line that ran from Houghton all the way up to Mohawk, north of Calumet, with stops in the township. In 1910, residents throughout Houghton County voted to create the Houghton County Road Commission, which maintains the area's roadways to this day.

Then came 1913. For the Copper Country, this year would turn out to be infamous.

The story of C&H begins in 1858, when surveyor and amateur geologist Edwin J. Hulbert uncovered a vast treasure — the Calumet conglomerate lode, a rich copper-bearing deposit that extended from Portage Lake all the way up to the Eagle River area. This portion of the Keweenaw's copper deposits proved the most valuable of all. Hulbert, with the financial support of investors, started the Hulbert Mining Company. Soon, the company purchased the land that contained the Calumet conglomerate and created subsidiaries, the Calumet Mining Company and the Hecla Mining Company. Eventually, the companies merged to become the Calumet & Hecla Mining Company, and under the management of Alexander Agassiz C&H would become a powerhouse. By the 1870s, C&H boasted a workforce of over 5,000 and shipped out over 80 million pounds of copper every year. At one point, C&H was the most productive copper mining company in the world.

A statue of Alexander Agassiz sits outside the old C&H library, now part of the Keweenaw National Historic Park. Photo by Lisa A. Shiel.

The company's policy of corporate paternalism — essentially treating its workers like children, with C&H as the parent — worked for decades. C&H became highly profitable and its policies helped nurture a thriving local economy. Instead of running company stores, C&H allowed businesses to grow up naturally, to serve the needs of the growing labor force. At the same time, C&H either gave workers homes to live in or provided land on which they could build houses. The tactic was meant to encourage families, and therefore a stable environment for their workers, rather than the bawdy lifestyle common to mining communities of the era.

Agassiz, though without doubt a skilled manager, adopted one particular policy that fostered tensions between C&H and its workers. He was staunchly anti-union. C&H's anti-union stance served only to increase the discontent brewing among the workers. As the company and the workforce burgeoned, the workers saw their relationship with management change from one of personal contact to a more detached affiliation. And of course, the language barrier grew taller as more and more non-English speakers entered the C&H workforce. Corporate paternalism was stretched to its limit as the family swelled larger and larger.

Labor problems first emerged in the 1880s, with small strikes, and tensions rose ever higher as the years passed, especially when the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) came to region in 1908 to court the workers. Miners blew up nitroglycerin in protests against the use of the explosive. But these scuffles would prove trivial in comparison to the summer of 1913. When C&H made public their plans to switch to one-man drills, a move that would cut numerous jobs, workers banded together — and with the help of WFM — they went on strike. C&H's mining operations went dark.

C&H, under the direction of Agassiz, refused to back down on their anti-union stance or on the one-man drills. These weren't the only grievances the workers voiced. Safety was a top concern, and an ongoing problem, for all the mining operations. In just one year, 1911, sixty-three workers had died in the mines. In 1912, more than forty workers died and over six hundred were seriously injured. The one-man drills not only reduced the workforce, but brought greater danger, since a man working a drill alone would have nobody to call for help. With all the dangers, and C&H's anti-union mindset, perhaps the strike should've come as no surprise to C&H. After all, despite the company's anti-union actions, by 1913 at least 2,000 workers belonged to unions.

A letter from the WFM to various mining companies found no traction, as officials outright refused to meet with the union or the workers. On July 23, 1913, the strike began — shutting down every mine in the Keweenaw, including C&H.

Violence erupted on both sides, sporadically. In an unprovoked attack that would go down in history as an egregious injustice, a half dozen men from a detective agency fired a hail of bullets into a boardinghouse south of Houghton, killing two men. Four of the shooters were convicted of manslaughter, another was acquitted, and the last man was reportedly whisked away to New York by C&H officials, where he served as a spy. At least one other shooting would follow, with a fourteen-year-old girl as the victim and no punishment for the perpetrator.

Strikers were chased, beaten, and generally terrorized by vigilantes working for the mining companies. This vigilantes called themselves the Citizens' Alliance. By December 1913, the atmosphere of rage and fear would climax with a tragedy that echoes down the halls of Calumet's history to this day.

What causes spirits to linger after death? This question has never found a definitive answer, and probably never will find one. People often speculate that unfinished business may keep some spirits grounded, while other ghosts may stem from great tragedies that trigger a sort of spiritual reverberation. These echoes lead to hauntings. In the case of Calumet's Italian Hall, the latter explanation seems likely.

The Italian Hall, created by the Italian Mutual Benefit Society, served as a meeting place for mine workers and their families. When the hall opened in 1889, C&H's general manager spoke at the grand opening festivities. In December 1913, the striking workers and their families gathered at the Hall on Christmas Eve for a children's Christmas party. The crowd included over five hundred children and nearly two hundred adults. Eyewitnesses reported that a man wearing a button identifying him as a member of the Citizens' Alliance rushed up the stairs to the second floor and cried, "Fire!"

Men, women, and children stampeded for the exits. Some have speculated that a few members of the fleeing mob tripped on the fifth step on the stairs. Whatever the cause, someone fell — and the domino effect brought down one after another, body after body, in a crushing pile-up that would kill upwards of seventy people — including as many as sixty children. As the panic escalated, children tumbled into a mass at the foot of the stairs and could not claw free, weighed down by the weight of their own bodies and those of the adults who got caught in the crush. Upstairs, at least a few children managed to escape through a second-story window with the help of a ladder. Although the exact death toll is unknown, thanks to the inefficient methods of reporting such tragedies in that era, no one disputes that at least several dozen died that night. The tragedy captured the attention of the entire nation. The Miner's Bulletin included this account, which epitomizes the horror of the Italian Hall disaster:

"One little girl who was jammed in the hallway in a dying condition begged one of her rescuers to save her. She grasped his hand, kissed it, then her little head dropped upon her breast and she was dead."

Recently, historians claim to have uncovered evidence that the Italian Hall disaster was not an accident, but rather the culmination of months of escalating terrorism and violence on the part of C&H and the other mining companies. Whether the man who started the panic in the Italian Hall worked for C&H or simply approved of its tactics, no one really knows. He may have been a vigilante working for C&H who decided to take matters into his own hands. Whatever the case, the actions of C&H and its cohort companies undoubtedly played a key role in the deaths at the Italian Hall, if only by fostering an atmosphere of militant opposition to the strike. At the time, many people blamed the Citizens Alliance, as made clear in a political cartoon published in a local Finnish newspaper. The cartoon shows Death himself hovering over the caskets of the dead carrying a banner that reads "Citizens Alliance."

The archway is all that remains of the Italian Hall. A historical marker offers testament to the tragedy, and plaques affixed to the columns memorialize the dead. Photo by Lisa A. Shiel.

Meanwhile, WFM president Charles Moyer seemed to take advantage of the disaster in a callous effort to further the union cause. On the night of the tragedy, as bodies were still being removed from the Hall, Moyer wired President Woodrow Wilson and other officials demanding an immediate investigation into the event. Then the day after the tragedy, Moyer issued a statement in which he claimed an outsider had started the panic, a statement that may explain where the rumor originated. Even today, no one knows for certain what happened or how many people died that night.

Moyer didn't stop there, though. In the days after the tragedy, he turned down money donated by locals who wanted to help. The funds amounted to thousands of dollars that might've aided survivors and helped pay for burials for the victims. A group of enraged citizens formed their own vigilante mob to hunt down Moyer, beating and shooting him. Moyer survived the attack, but made claims that C&H general manager James MacNaughton had instigated the attack. Later, Moyer recanted his claim of MacNaughton's involvement. It seems that both sides in the miners' strike would use any means necessary to win the battle. In the end, C&H would be victorious. On April 12, 2014, the workers voted by an overwhelming margin to terminate the strike.

C&H kept mining copper ore into the 1960s, although the company never again reached the heights it had achieved in its heyday.

The Italian Hall as it looked the morning after the fire. This historic photo appears on a pedestal at the memorial site. Photo by Lisa A. Shiel.

Sites of tragedies, where many people died, often inspire stories of ghosts haunting the locations. Italian Hall has proved no exception. Over the years, rumors have circulated that speak of spirits inhabiting the place where once the Hall stood. Now, a monument to the tragedy — consisting of the original building's archway and a plaque — stands in place of the building.

People visiting the site have reported feeling a presence there. A ghost hunting team from Calumet Paranormal, led by John Grathoff, visited the site late one night to check out the claims. A sandstone archway — once the doorway of the Italian Hall — stands as the only physical remnant of the disaster. Plaques mounted on the archway pillars offer prayers and calls to arms. "Sleep in heavenly peace," reads one. Another admonishes, "Mourn for the dead; Fight for the living." A brick path leads through the archway, and then circles around sandstone benches and a historical marker.

John and his team arrived around midnight and proceeded past the archway to the benches, where they sat down to wait. They set up their K2 EMF meter so that everyone could see it. Because this meter detects electromagnetic fields through a wide range of frequencies, ghost hunters often employ it in their investigations. The idea is that ghosts create spikes in EMF, which meters like the K2 will detect. When the meter senses a change in EMF, lights flash on its face, alerting the ghost hunters that something is happening. On this night, as John and his team sat among the ruins of the Italian Hall, their K2 meter stayed quiet, its power light glowing steadily. John compared the atmosphere that evening to sitting in his living room at home.

As they often do, the team decided to try an EVP session. EVP stands for electronic voice phenomena, and it refers to voices heard on an audio recording that were not heard at the time the recording was made. A member of John's team asked, "Is anyone with us?" The K2 meter did not flash. No one in the group heard a response. The night remained quiet and dark as the team waited in the shadow of the archway. When nothing happened, the team headed home.

Later, they listened to the recording they had made that night and discovered something that would send shivers down anyone's spine. On the recording, after the team member asked if anyone was there, a voice could be heard replying, "We are all here." The voice sounded like a child.

Could the spirits of the dozens of children who died in the disaster haunt the site today? Might one of them have responded to the ghost hunter's question? If great tragedies can trigger hauntings, then the Italian Hall disaster certainly qualifies. More than a tragedy, the events of Christmas Eve 1913 remain mysterious in many respects. Who shouted "fire"? How many died? Do their spirits live on at the site?

Questions abound. Answers are elusive.

Plaques like this one adorn the columns of the Italian Hall archway, the sole remains of the building. Photo by Lisa A. Shiel.

In 1898, the village council of Red Jacket realized their township lacked a crucial element necessary for any civilized city. They needed a real opera house. The council voted to construct a new, modern opera house to replace the Red Jacket Opera House, which resided on the second floor of the village hall. Maybe the Marquette newspaper's heralding of the Calumet area as "the most cosmopolitan town in America" had something to do with the council's decision. After all, how could they live up to such a moniker without a true opera house? Either way, two years after receiving the high praise, Red Jacket implemented a plan to construct a new opera house.

Within hours of the vote, the council contacted architect Charles Shand of Detroit to garner his participation in the project. Shand was told to spare no expense in designing the new opera house. How could anyone put a price on elegance and sophistication? By year's end, construction had begun on the Calumet Theatre. The village hall would be expanded to accommodate the new opera house. Within two years, the Theatre was finished at the discount price of $71,000 — the equivalent nearly $2 million today. At the time, the Theatre stood as the only municipal opera house in the country. Everyone waited for opening night, anxious to see what their tax dollars had bought. Would the opera house live up to its hype?

On March 20, 1900, the Calumet Theatre opened for business. Twelve hundred people turned up on opening night, filling the house to capacity, despite the high ticket prices. For its grand opening performance, the Theatre hosted the operetta The Highwayman, written for Broadway by Reginal de Koven. The Calumet & Hecla Mining Company orchestra provided the music for the evening. Patrons raved about the architecture, the murals, and of course, the entertainment. Five grand murals spread across the vaulted ceiling illustrated the concepts of painting, music, drama, poetry, and sculpture. Above their heads, patrons glimpsed a globe-shaped chandelier constructed from copper and equipped with over a hundred electric light bulbs. The chandelier, along with a copper roof, served as a nod to the importance of red metal mining in the region. A glorious clock tower, capped with a bell tower, occupied one corner of the building.

The Calumet Theatre, as it looks today. Located in downtown Calumet, it's a must-see for every tourist. Photo by Lisa A. Shiel.

After such a successful opening night, it might seem hard for an opera house to keep up the momentum, but the Calumet Theatre did just that. Theatrical royalty made pilgrimages to the Theatre to perform before star-struck audiences. Famous names over the years included Lillian Russell, Helena Modjeska, Sarah Bernhardt, Douglas Fairbanks, and Lon Chaney. The renowned composer and marching-band leader John Philip Sousa, dubbed the March King, also appeared at the opera house.

The mining strike of 1913-14 took a heavy toll on the opera house, as attendance plummeted in the wake of the strike itself and of the unspeakable tragedy at the Italian Hall. The opera house even served as a makeshift morgue for the bodies removed from the ruins of the Hall. Never again would the Calumet Theatre regain its standing as one of the preeminent opera houses in the nation. The year 1918 brought more bad news for the Theatre. First, Copper Country succumbed to an outbreak of the infamous Spanish flu that swept through the nation in that year. The epidemic shut down the Theatre. Then, just weeks after the opera house reopened, a fire broke out after someone left a cigarette burning in the backstage area. The beautiful copper chandelier was destroyed.

The main doors of the Calumet Theatre. Photo by Lisa A. Shiel.

The fire marked the end of the Theatre's glory days. By the 1930s, the opera house functioned chiefly as a movie theater and would continue in that capacity well into the 1950s. In 1958, summer stock returned to the Theatre, marking the end of professional theater's three-decade absence from the opera house. The Calumet Theatre would bid farewell to summer stock a decade later. By 1971 the Theatre, now leased from the village by the Copper Country Intermediate School District, achieved landmark status — literally — when the National Park Service granted the Theatre the status of National Historic Landmark. Over the subsequent decades, the Calumet Theatre would undergo multiple efforts at renovation and restoration. The murals would be restored to their original glory; the chandelier, however, would not be recreated. The lack of photographic documentation for the copper chandelier's appearance has prohibited any reconstruction.

In 1993, the Theatre became a Heritage Site in the Keweenaw National Historic Park, a unit that spans multiple locations through the Keweenaw, from Copper Harbor to south of Houghton. Today, the Theatre once again hosts dramatic and musical performances, thanks to visiting artists and the Calumet Players, a community theater group. Performances and self-guided tours of the landmark draw in about 20,000 visitors each year.

But some people say the Theatre hosts visitors of another kind as well — the kind who should've left long ago but refuse to depart. They are the spirits of the opera house.

The Calumet Theatre's past is as dramatic as many of the performances visitors have enjoyed there. Mass deaths (possibly mass murder), a pandemic, a fire — this building has enough tragedy and destruction in its past to warrant a slew of hauntings. And, as it turns out, many people believe the Theatre is home to several ghosts. According to local ghost hunters, the current management refutes claims the building has any spooks. Their denials have done nothing to quell the stories.

The best-known ghost that purportedly resides in the Theatre belongs to a Polish actress named Helena Modjeska. According to the website of the Helena Modjeska Society, the madame became the most well-known actress in the United States during the nineteenth century. She excelled at Shakespearean roles — which give any actress the chance to sink her teeth into dramatic and haunted characters, as well as the occasional comedic part, penned by the immortal bard. These haunted characters may have inspired the lady herself to linger after death. She has been quoted as saying, "It is a hundred times better to suffer and live than to remain asleep." Maybe she took the saying a bit farther, deciding to live on after shedding the mortal coil. Modjeska's portrait hangs in the Calumet Theatre, a testament to her fame back in the glory days of the opera house. Modjeska died in 1909 at the age of 48, and although she died in California, tales of her afterlife surround the Calumet Theatre.

Legend says that whenever her portrait is removed from the wall, inexplicable things happen inside the Theatre. Lights go out and come back on of their own volition. Strange banging and crashing sounds erupt elsewhere in the building, but investigation reveals no source for the noises. Others have felt chills from mysterious breezes inside the building, while still others insist they've heard eerie melodies echoing through the halls of the historic opera house, despite finding no source for the music.

Madame Helena Modjeska. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-99177.

The madame herself has made guest appearances before various people, startling them with fleeting glimpses of the elegant, dramatic lady. During the summer of 1958, the Calumet Theatre hosted a production of Shakespeare's The Taming of the Shrew, with an actress named Adysse Lane playing the lead role of Kate. In the midst of a vital soliloquy — a lengthy monologue that relies on one actor's performance to drive the scene forward — Lane abruptly lost her place in the script. At a loss for words, unable to recall the lines, in desperation she resorted to waving her hands about in gestures she prayed would distract the audience from her sudden silence. Whether the tactic worked or not is hard to gauge, but Lane valiantly struggled to keep her performance going.

Just when the actress thought she'd blown the entire scene, and would have to walk off the stage in disgrace, Lane felt an unknown force raising her hand. The otherworldly power lifted her arm until her hand pointed at an area on the Theatre's second balcony where, behind a spotlight, she glimpsed the figure of a woman. It was, Lane claimed, none other than Madame Helena Modjeska. By this time, the audience may well have wondered about Lane's unusual performance of the scene. But as the living actress watched her long-departed counterpart on the balcony, Modjeska mouthed the lines for the soliloquy, thus rescuing the forgetful damsel from a very embarrassing distress. Lane got a good enough look at the spirit to describe Modjeska's dark eyes and fair skin.

A reporter from the Houghton newspaper once spent a night in the opera house in hopes of meeting Madame Modjeska in person. The reporter sat in the performance hall reading a book, by the eerie light of the exit sign, hoping for a glimpse of Modjeska herself. As the night wore on, the reporter began to wonder if anything interesting would happen, or if this would go down in history as yet another average night in a spooky old building. In an effort to encourage the ghost — or ghosts, as the case may be — the young woman walked to the portrait of Modjeska, carefully removed it from the wall, and set it down on the floor leaning against the table that stands below the spot where the portrait normally hangs. Messing with the portrait is, according to legend, one thing sure to rile up the Shakespearean ghost.

The reporter then returned to the theater proper and sat down to write an article on her laptop computer. A water bottle rested atop the nearby piano, on its closed lid. Suddenly, the bottle toppled over and rolled across the piano lid as if someone had touched it — but no one had. The reporter set the bottle upright again, and resumed typing. Had the water bottle fallen due to a draft or a freak vibration in the floor?

As the reporter grew more and more sleepy, she kept thinking she caught glimpses of something in the balcony, but a second glance always revealed emptiness there. Then, just when the reporter was getting ready to leave, she heard the sound of heavy breathing emanating from the rear of the hall. The breathing noise drew closer and closer, but seemed to dissipate the nearer it came to the young woman. Finally, the sound faded away altogether. Uncertain about what had happened, the reporter fled the Theater. Had she encountered one of the resident ghosts? No one can say for certain, but the reporter was not the first or the last to report an unexplained incident while visiting the landmark.

The paranormal history of the Theatre, although disputed by management, tells of other ghosts besides Madame Modjeska. Witnesses have reported hearing tortured screams reverberating through the building, and some believe the screams belong to Elanda Rowe. The legend speaks of the little girl dying at the hands of murderer on the very grounds where the Calumet Theatre now stands. Murders, especially of children, provide the backdrop for many hauntings.

Another spectral story involving the Calumet Theatre revolves around yet another reported murder. This crime took place, the story goes, back in 1903 when an adult male was killed on the grounds of the opera house. As with Elanda Rowe, this ghost screams in the dead of night, reliving his horrific death.

The only apparition of a person verified to have both lived and died is Helena Modjeska, and no one knows why she might choose to haunt the Calumet Theatre, considering how many other theaters she visited during her illustrious career. Elanda Rowe and the unnamed man remain ghosts in life as well as death, with little known about the veracity of the murder tales. What we do know is this — multiple witnesses have reported unnatural goings-on at the Calumet Theatre, a place haunted by real tragedies as well as legendary ghost stories.

Where did professional hockey get its start? In the Copper Country, of course. Canada may like to claim hockey as its proprietary sport, but the professional version of the ice game had its beginnings in the Keweenaw Peninsula of Michigan, where locals formed the first professional hockey league back in 1904. Although the league lasted just three years, dying out in 1907, it stands as the first of its kind. Today, hockey is still a big deal in the Copper Country, and teams battle for supremacy of the ice in the Calumet Colosseum. But the Colosseum hasn't always been an ice rink. Its varied past may explain why the building seems to host at least a few spirits — not of the sort imbibed by hockey fans to celebrate their team's victory, but of the deceased kind.

The Calumet Colosseum. Photo by Lisa A. Shiel.

The Colosseum was built in 1913 as a hockey rink, and the following year saw the first game played on its ice. The headquarters of the Calumet & Hecla Mining Company lay right across the street from the Colosseum. Miners even helped out with the construction of the rink by lending a hand during installation of the artificial ice.

By 1942, however, the rink had been sold to the State of Michigan. A fire had destroyed the National Guard armory in Calumet, so the government needed a new base for the Guard's operations. An addition tacked onto the back of Colosseum provided space for the armory. Even while the building served the National Guard, the Calumet Hockey Association leased the rink during each hockey season, from October through April. Then, in 2005, Calumet Township reclaimed the Colosseum by striking a deal with state — in exchange for ownership of the building, the township would grant the state twelve acres of land on which they could build a brand-new armory.

The main doors of the Calumet Colosseum. Photo by Lisa A. Shiel.

A million dollars in improvements have spiffed up the Colosseum, but care has been taken to retain the historical character of the building. Today, the Colosseum stands as the oldest continually operated hockey rink in North America. The building even hosts the International Frisbee Hall of Fame, and it also includes a ballroom on the second floor of the armory addition. With a history of military and civilian use, it's no wonder the Colosseum houses ghosts.

Ghosts often seem to be frozen in a particular time and place, reliving tragic events or simply hanging around after death. The Calumet Colosseum, like many historic buildings, has apparently become home to its own spirits frozen in time. Over the years, visitors have reported multiple phenomena — from a disembodied voice humming circus music to glimpses of "shadow people" (dark, shadow-like figures with no discernible features). John Grathoff and the Calumet Paranormal team have visited the Colosseum on more than one occasion to investigate the claims of ghostly activity.

During one visit, the team heard a disembodied voice whistling circus music as well as the sound of a radio playing, though no radio was found. During another investigation, the team had some truly spooky experiences in the Colosseum. A group of nine attended the investigation, including a reporter from Marquette's TV6 News. Four people, among them the reporter, stayed in the ballroom in hopes of seeing a shadow person, while the rest went down to the locker rooms. In the ballroom, John spoke to whatever spirit might be in the room, asking it to do something to demonstrate its presence. As soon as he had spoken the words, the reporter's camera battery died — even though she had just recharged it. John described it as "like somebody had walked over and flipped the switch on [the camera]. The battery was totally drained."

While the reporter changed her camera's battery, the team could hear something "shuffling around" in the nearby restroom and the sound of the stall doors opening and closing. The team decided to check out the noises, and headed toward the restroom. As they approached the doorway, they could see into the room beyond. There, inside the restroom, they witnessed a pair of legs — with no torso attached — walking around in the space. Suddenly, the legs bolted out of the restroom, morphing into a "black, shadowy mass" as the thing flew right in between the shocked team members. The reporter, according to John, "just about dropped her camera and ran out of the building."

The team returned to the ballroom a few minutes later. At the far end of the room, they spotted the shadow being moving around as if it were looking for something or attempting to perform some task. John and the gang tried to draw closer to the shadow figure, but it vanished in the blink of an eye.

The photo of a shadow figure captured by John Grathoff and his team at the Calumet Colossseum. Photo courtesy of John Grathoff, Calumet Paranormal.

Close-up of the shadow figure. Photo courtesy of John Grathoff, Calumet Paranormal.

Later, the two halves of the investigation team opted to switch places so that John's group would be in the locker room downstairs. The other group had reported hearing strange noises, but hadn't seen anything. During the switch, as John's group walked down the stairs, one of his teammates took some photos. When they looked over the photos after the investigation, they discovered a dark silhouette in the background of one photo. This "shadow person" appeared to be standing inside a doorway at the end of a hallway opposite where John's group had been standing at the time. At first, the team thought they'd simply captured the reporter's reflection in the glass alongside the doorway. Further research demonstrated, however, that even with her camera held on her shoulder, the reporter did not stand tall enough to account for the shadow figure. The dark silhouette was too tall.

Once in the locker room, John's group experienced more strange activity. John knocked out a rhythm known as "shave and a haircut," stopping in the middle of the pattern to ask any presence in the room to finish it for him. The team had recorded the session in case they might catch any EVPs. When they listened to the recording afterward, they heard a knock responding to John's, finishing the pattern he started.

Do ghosts inhabit the Calumet Colosseum? Any building with a long history, like the Colosseum's, certainly has the potential to foster hauntings. And, as the ghost hunters learned through their research, the Colosseum did at one time host a carnival. The whistling ghost could well date back to that era.

Calumet has a long, and often violent, history — from the Copper Strike of 1913-1914, with its tragic climax, to tales of opera-house murder. Whether or not you believe the ghost stories, one fact is disputable. This village has a history ripe with fodder for just such tales. If tragedy and violence give birth to hauntings, then Calumet surely is home to at least a few earthbound spirits.