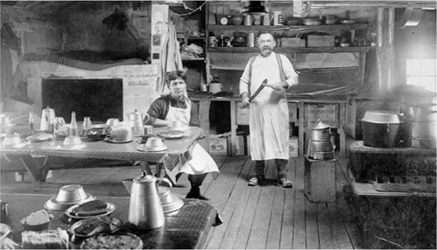

The dining room at August Mason’s lumber camp, Brill (Barron County), early 1890s.

WHi Image ID 1961

AS THE NEW STATE CONTINUED TO PROSPER IN the nineteenth century, many tasks associated with economic growth had to be performed by large crews of men, many of them single, who lived together for the duration of the work. There were married men in the crews, too, working for the grubstake to reunite their families and settle down.

Some communal undertakings were performed in settled areas and served a social function besides—barn raisings, church raisings, and threshing activities at harvest time. They involved an equally diligent crew of women working in the kitchen. Most, however, were exclusively male enterprises carried out on the edges of the frontier: railroad survey and building gangs, loggers, rafters, Mississippi steamboat crews.

Whether in community or in wilderness, the work was hard and long. Prodigious quantities of food were required to keep the laborers going, giving rise to a unique culinary tradition in fact and fable.

In one way or another, threshing time was one of the high points of the farm family’s year. For the children, it was a gala event, a visit of near and far neighbors for at least one whole day: “When I was a small boy, there were three annual events in my life that I looked forward to with great eagerness. First there was the 4th of July ... then Christmas ... and third was the visit of the threshing machine.” For the farmer, it was largely the economic matter of getting his crop in and assessing the success of the growing year. For his wife, it was a concentrated period of intense, hard work well larded with heaping portions of culinary competitiveness and pride. “It was no secret that the wives in the neighborhood vied with one another to see which could furnish the most satisfactory dinner,” recalled a Madisonian of German heritage about his 1880s boyhood in Sauk County.

Farmers near Black River Falls rest on a threshing machine.

WHi Image ID 53677

Preparations began days before the threshing crews were expected. Some breads, cakes, pies, and puddings were made in advance; fresh meat was butchered and hung. While they worked, the women of the household no doubt prayed for good weather, for in the days before refrigeration, a rain meant postponing the threshing and the spoilage of much of the food.

Usually, neighbor women came to help out when the crews were working, but the primary burden, of course, lay on the farmer’s wife. Her day (or days if the farm was large) began as early as 4 a.m., when she would need to get breakfast ready. Then there was a forenoon lunch to prepare and serve out in the fields, a dinner at noon, another lunch in the fields in the afternoon, and an evening repast when the day’s work was done. The last pot and pan usually was scrubbed and put away about 11 p.m. Though the neighbor women helped, all food was prepared in the family kitchen on the family stove, which had to be kept going red-hot all day, no matter how high the temperature outside. No doubt most shared the feeling of Jane Kelly of Cottage Grove, who noted in her diary on September 18, 1873, after four days of threshing (counting some lost time for broken machinery): “Finished Threshing today and I am so glad.”

The annual residence of the threshing crew (the term encompassed silo fillers, hay balers, harvest hands, etc.) was a tradition that lasted well into the twentieth century. From 1912 to 1916, Nellie Kedzie Jones, a pioneer in the development of the study of home economics, wrote a column for The Country Gentleman from her home in Marathon County. In one of them, couched in the form of a letter to a mythological city-bred niece who had married a farmer, she outlined the best way to feed a work crew:

I would begin my baking about three days beforehand with a big batch of drop cookies. At the same time the pie crust, if you want to use pie, can be mixed up ready for the wetting and set away in the ice box. Do the bread making the day before. At the same time boil and bake a whole ham. This will make your cold sliced meat. A big ham ought to boil at least four hours, and bake in a slow oven two more. The night before peel “a heap” of potatoes; allow not less than four large potatoes for each man per meal and a few more for the dish. Set them away, covered with cold water.

Just as soon as you can find out when the threshers will be getting into your neighborhood, even a week or ten days beforehand, I would make up some pork cake or some other moderately rich fruit cake. If you should not need it there will be no loss, for it will keep for some time. Better have too much than too little. Ice cream is one of the easiest desserts for a crowd. The mixing is practically nothing; one of the men will freeze it and pack it away hours before it is needed. It is easily served.

Hot food promptly served makes more of a hit with a crew of hungry men than something so elaborate the service is slow and the food cold. However, I would have a cold sliced meat so that everybody could begin as soon as seated, for a dozen men are not served in a minute with the hot meat. They eat no more when you have two kinds than when there is but one; all would want a second helping anyway.

A big dish of cabbage salad on each end of the table will be appreciated by all hands. By threshing time you will have ripe tomatoes. A big dish of these, sliced and covered with cream salad dressing, is easily prepared, and there is no serving, for the men will help themselves, putting them on their plates just as they do the cabbage salad.

Put on three plates of bread and three plates of butter, allowing two slices for each man, and then watch the bread plates for further devourments. So, too, with the coffee. Have plenty. Plan at least two cups for each man.

The hay balers, however, when the baling is done out in the meadow some distance from the house, can be treated differently. With the dew on the hay they will start late in the morning and so will work late at night, to get in a full day. They will need a lunch at four in the afternoon.

The midday meal can be served in the field, picnic-fashion, to the real pleasure of the men, to the saving of their time and the lessening of your own work. I have served a mile and half from the house and got the dinner there hot. Really this serving in the field is easier part of the time than in the house. The trick of it all is in getting rid of the nonessentials. No frills but food fills the bill with the farm labor. The men and horses can better spend the time out of a short morning resting in the field than journeying to the house and back.

The question of suitable drinks for the men in the field in hot weather is an important one. In the old days, grog aplenty was served with striking results, literally striking results, which were not at all on the program. That has most recently passed. Some like buttermilk, others could not be hired to touch it. There is oatmeal water, root beer or a harmless home brew, and so on, but I have found that canned fruit juice, properly diluted with well water—do not have ice water—and toned up with citric acid comes as near being universally acceptable as any drink that I know of.

Taking a break from threshing work for a cool drink and conversation.

WHi Image ID 53684

The generosity of the tables set for threshing crews was fostered as much by the farmer’s wife’s pride in her reputation as a fine cook as by need. But even in operations that were purely profit-making, competitive enterprises, the importance of large, hearty meals was unquestioned.

On the Mississippi steamboats in the 1880s and 1890s, for instance, most companies and captains realized that the cook had a lot to do with keeping a crew. As Captain George Winas of the Juniata used to say, “I want to pay them well, feed them well, and then I want them to work like hell.” In 1899 the Juniata budgeted fifty-seven cents a day for each of eighteen men in the crew, a generous amount of money in those days. And that didn’t include the cook’s wages, which ranged from eighty to ninety dollars a month, or that of the cook’s helper.

Seen here docked in La Crosse, the steamboat Diamond Joe traveled the Mississippi River in the late 1800s.

WHi Image ID 48622

On that budget the men sat down to a breakfast of fried potatoes, ham and eggs, pancakes, bread and butter, rolls, cookies, gingerbread or snaps, and coffee; a dinner of meat roast, mashed potatoes, two or three kinds of vegetables, and pie, cake, and ice cream for dessert; and supper, a lighter version of dinner, often with cold meat instead of hot. Fish—catfish, bass, and pike—provided fresh by fishermen who brought their wares to the boats, was served at least once a week. During the hunting season, there were ducks; in other seasons, foods like berries were bought in La Crosse and Trempealeau.

The cooks—universally men—were experts at stretching their food dollars and using leftovers. Harry G. Dyer, who worked on riverboats in the 1880s and 1890s, remembered a fine cook, George Whalen, who once served a dessert of boiled rice and sauce. It didn’t go over well, and there was plenty left. “The next morning it went into a big frying pan, then a big slice of ham or two diced, then a can of tomatoes; the diced ham, rice and tomatoes were then browned, seasoned quite highly, seasoned with a touch of red pepper, and then it was ‘jambalaya’ and fine for a hungry river man.”

Sometimes, though, the cook went too far in his cost cutting. On one of Dyer’s journeys, the cook kept serving butter so strong that it “was perfectly able to walk.” It was still on the table on the return trip, and the cook informed the complaining crew members they would have to use it before they got any more. “Well, that night, ‘the boys’ used about five pounds of that butter to grease the door knobs in the cabin and about ten pounds more was used to decorate various kitchen utensils, drawer pulls, and anything else that they thought would look better with a coat of butter. The next day the clerk went ashore at Lake City to get some butter.”

The ship’s officers must have welcomed the fresh butter, too, since on most river boats all crew members customarily were served from the same pot. Chancy Lamb, head of the C. Lamb and Sons steamboat company, used to instruct the cook to “cut everything in two in the middle and send half of it each way,” meaning that the officers ate what the men did.

But it was in the logging camps where the importance of a full belly was indisputable and the status of the cook exalted. Some cooks were better than others, naturally, and some logging companies more generous than others in providing a larder of greater quality and variety. But there was general agreement, as one logging manager noted, that “a good cook meant a contented crew and a contented crew meant a good cut of timber. Nothing disrupted a crew like poorly prepared food and a sloppy way of putting it on the table. A grouchy ill-tempered cook added to the dissatisfaction.” And it was in the logging camps that food and meal traditions have been yeasted into the North Woods folk tales of today.

The gargantuan meals of logging folklore were well rooted in fact, for logging in those days was strenuous work, and the cook and his assistant (called the cookee) also worked mightily to provide them. Then too there was not much else to do in those all-male societies, isolated in the wilderness, except to work, eat, sleep, and think up practical jokes. The quality and quantity of food thus assumed greater importance than in places where other diversions were available.

Consequently, the cook shanty was usually the best-constructed building in the camp, often in the early days, before the 1880s, accommodating the sleeping bunks as well. The shanty housed the stoves and the dining tables, the latter frequently set for more men that they could comfortably accommodate—“with no elbow room, it was quite a trick to get an arm loose to spear a potato or a slice of bread.” The food was usually served on well-scrubbed but bare pine-board tables set with tin bowls, plates, and mugs and bone-handled knives and forks.

The day for the cook and his cookee started about 3 o’clock in the morning or half past, when they would prepare the spread required to get a lumberman going: buckwheat pancakes (begun the night before with sourdough starter and made on a griddle that covered the whole top of an eight-lid stove), oatmeal, hash, potatoes, fried salt pork, beans, blackstrap molasses, fried cakes, and lots of black coffee sweetened with brown sugar.

Cleaning up after breakfast merged with preparing the noonday meal, which was usually brought out to the men by the cookee carrying about an eighty-pound barrel-pack on his back. (When the cookee needed to rest, he would find a tree stump of suitable height, back up to it, and rest the pack for a spell.) The pack would have been filled, for example, with huge quantities of pork and beans, slabs of homemade bread, crusty sugared fried cakes, and molasses cookies. The cookee summoned the men to this repast by blowing on a tin lunch horn or into the neck of a whiskey bottle with the bottom broken out.

Dinner was dished up back at the camp: potatoes with brown gravy; fresh meat (depending on the season); red horse (salted beef); pea soup; stewed dried prunes or dried apples; rice pudding; the ubiquitous fried cakes; pie of dried apples, prunes, or raisins; and coffee or tea. And, of course, homemade bread, mixed up in pine troughs large enough for a half-barrel of flour at a time. Salt and pepper were passed in pint basins and sprinkled on the food with a knife.

In a Hayward lumber camp, cook and cookee await the hungry crew.

WHi Image ID 1962

CHRISTMAS WAS A SPECIAL TIME to men working in logging camps in the remote North Woods, just as it was to farm and city folk. “For two weeks before the great day, things took on a brighter hue,” recalled Otis W. Terpening years later. “At least they seemed to. The lads were better natured than usual. And why shouldn’t they be. Some had left their families and kiddies early in the fall, with the understanding that at Christmas they would all be united again. While others thought of the sweetheart back in the settlement. Then we had a kind with us that I can’t describe in this up to date language. But us Jacks called them lushers: a class that was shunned by the better class of Lumberjacks. For the only thing they seemly thought of getting out of life was a big drunk and a feed of ham and eggs. As there was no drinking allowed in camp, it was real hard on them.

“And they [all] seemed to hail Christmas as a time of getting out of their bondage. As the day drew near the real Christmas Spirit seemed to prevail. And in the snatches of song that we would hear in the woodland during the day there was a real ring of joy in them. And in the voice of the Jacks on Christmas morning as they wished one another Merry Christmas. And to hear one Jack say, ‘Thanks, pal, I hope you live forever and I live to see you die.’ We seldom ever worked on Christmas, but the day was spent in visiting, darning our socks and mittens. While some spent their time in playing cards and listening for the cheerie sound of the dinner horn, saying come and eat, eat. The cook would always have something extry, and a plenty of it.”

No one could deny there was plenty: “There was roast beef, brown gravy, good homemade bread, potatoes, shiny tins heaped with golden rings called fried cakes, and close to them a pumpkin pie baked in a ten-inch tin, about one and-a-half-inch deep, and cut in four pieces. Any other day to a Jack it was one piece, but today it was Christmas. It only came once a year and help yourself, if you wanted a whole pie you was welcome. And rice pudding black with raisins, dried prunes, or the old-fashioned dried apples for sauce. Black coffee sweetened with brown sugar. And tins full of sweet cookies. They were white and had a raisin in the center of them. Did we eat, I will say we did! I have eaten many a Christmas dinner in camp. And some here on the farm, but the best was in camp. Just one more with a jolly crew, and I would be willing to say, ‘Life is now complete.’”

After Christmas dinner, which was served at noon, the loggers relaxed until it was time for supper, which was almost a repeat of the main repast. Then, Terpening continued, “Some would get out the old greasy deck of cards and climb into some pal’s top bunk for a quiet game of poker, while others took to the old-time square dances. The ‘ladies’ had a grain sack tied around their waist so we could tell them from the gents. And woe to the one that stepped on a lady’s toe, and did not apologize. And do it quick. Or it would be one quick blow and a Jack would measure his length on the floor. Then it was the first two gents cross over and by the lady stand. The second two cross and all join hands. And we had to have a jig every set.”•

The makings for all this were purchased in quantity. In 1884, for instance, the clerk for the Joseph Dessert Lumber Company of Mosinee recorded purchases of “18 pounds salt, 24 cents; 14 pounds pork, $1.12; 14½ pounds venison, $1.02; 9½ pounds beef, 54 cents; 4 pounds soap, 20 cents; 5 pounds codfish, 40 cents; 6 pounds steak, 60 cents; 29 pounds butter, $5.22; 6 boxes pepper, 50 cents; barrel of cranberries, $5; 10 pounds veal, 70 cents; 120 pounds wheat, $1.50.”

Flour, sugar, and rice came in barrels and were kept with root vegetables and dried foods in a small cellar under the cook shanty. In the cold of winter, storage of fresh meat was no problem; a small building set off from the warmth of the cook shanty was usually built for the quarters of beef, dressed hogs, lard, salt pork, and sausage.

The consuming of these enormous meals was as ritualized as the serving. Though there was considerable yelling, shoving, and pushing around the door before the meal horn was sounded, silence reigned at the table; there was to be no talking except to ask for something. As one old-timer recalled, “If some one happens to laugh, the cook whistles or raps with a knife handle and we all know that means silence.” Every man had his special place at the table; a change in seating ultimately required the cook’s permission. Occasionally, a new man would sit in someone else’s place and would get just one warning before the laying on of hands by the rightful owner; it was considered cowardly to be driven from your place.

Like the atmosphere, table etiquette was rude. Most men, no matter what their background, “cast aside everything in the way of politeness and table manners. It’s ‘dog eat dog’ if you get enough of what you want.” But though all-you-can-eat was fundamental in logging camp dining, there were limits that, if exceeded, brought forth insulting references to porcine behavior. (One lumberman remembered a breakfast when a platter of six eggs was placed on the table and grabbed by a man who dumped all six onto his plate. A tablemate’s comment was: “Well, I like pork, but damn a hog.”)

Really epic eaters had to have tough skins to match their strong stomachs so they could withstand the reaction of their comrades. The story was told of a turn-of-the-century logger—described as a porcine cross between a Poland China and a Chester White—with a particular fondness for the weekly meat pies baked in six-quart basins. Each man was served a quarter of the pie, but the “hog” would “hurry and eat his piece, and then just to be friendly, would eat one more.” The cook finally had enough and placed before him a six-quart meat pie with two large kitchen spoons neatly crossed on top. “The hog asked for a plate, but Ed [the cook] told him he was through feeding hogs from a plate, but that he ordered the wood butcher to make him a trough, and it would be ready for him for supper. That noon hour every one of us had some wonderful suggestions to make to the hog in regard to eating out of a trough. He could not stand the gaff and packed his turkey and hit the grit.”

On occasion, guests would be entertained at camp, enlivening the usual mealtime routine. At such “soirees,” a better grade of coffee was sure to be served, and conversation was permitted. The spirited conversation, and perhaps an added course or two, promoted more leisurely dining.

When it was time to float the logs down the rivers, the culinary traditions of the North Woods went along with the raftsmen in the cook shanty affixed to a log raft. Breakfast and supper were served at the shanty, but, as he had in the woods, the cookee took the first and second lunches at midmorning and midafternoon out to the men in tin hampers.

On the way to the mill towns along relatively sparsely settled stretches of river, shanties would be tied up at a bridge for a day or two for shopping forays to local farms, especially for chickens, which were “at a premium,” and fresh pork. After the logs were milled, huge rafts of lumber were assembled, the cookstove put on board under a temporary shelter, and the trip to market at St. Louis or even New Orleans began. Cooks on these lumber rafts had the luxury of landing in river towns and cities for store-bought items like syrup, salt, dried apples, and flour.

Occasionally, these mobile provending practices were highly unorthodox. Raftsmen were fond of fish but had no time to dangle a line and catch some. Their solution was to trail a drag line with a heavy iron weight from the back of the raft, thereby gathering in setlines strung across the river by fishermen on shore. From time to time, the drag was raised, the fish (which almost always included fine catfish) removed, and the hooks and setlines tossed overboard. “There were enough catfish for supper and some left over, which were sold in the next town.”

While lumberjacks were generously packing the food away, railroad survey crews were tramping over difficult terrain throughout the state performing their arduous labors on a great deal less. Charles Monroe, a member of the crew doing the Penokee Survey in Ashland County for the Wisconsin Central Railroad in 1881, wrote home to his mother in Ohio that “we live on bacon, ham, beans, potatoes, rice, canned tomatoes, with canned peaches and blackberries for variety occasionally, tea and coffee. Our cook makes very good bread, and there is generally enough to satisfy one of one sort or another. I am awfully tired of salt meat though. Yesterday we had some codfish. The cook has no stove, he bakes bread in open tin ovens, laid on the ground in front of a log fire, shaped so as to gather and intensify the heat.”

Every once in a while, the crew would get back to the base station and stoke up on better meals, making the subsequent return to camp meals even more dreary. (This situation was made even worse when the regular cook was lured away by another outfit and Monroe and his companions had to share the cooking chores.) After a sojourn at the base, where he had a big supper on Saturday and then an equally big breakfast and dinner on Sunday, Monroe “came back, somewhat reluctantly, to camp Sunday evening. We had nothing in camp but salt pork, biscuit and coffee for a couple of weeks. My Thanksgiving dinner consisted of three biscuits and some coffee, and was eaten out on the line where we were at work. We shall fare better after this, probably, for we have just received a lot of supplies, and have got a new cook.”

Construction workers on the Milwaukee, Lake Shore & Western railway line, Marathon County, circa 1840.

WHi Image ID 24556

In the nineteenth century, compensation for many types of work in town and country included one or all meals. Lars Olsen, for example, writing home to his mother in Norway from Sand Bay in Manitowoc County in 1854, reported: “The lowest pay here is sixteen dollars a month and board, but the board is not rotten herring and gruel here as it is many places in Norway. Here we eat three times a day. In the morning we eat breakfast at 6:30 and begin work at 7, and for breakfast we have every morning fried pork, cold meat, coffee, wheat bread, butter and cookies, and for dinner boiled meat, pork, and potatoes and for supper at six o’clock we have fried pork, meat and potatoes, tea, bread and cookies.”

Not all employers were so generous. For instance, Daniel Thomas, a Welshman, worked as a farm laborer and handyman in the Hartland area of Waukesha County after he arrived in Wisconsin in 1851. He noted in his diary the occasion when he was served turkey—“for the first time in twenty years”—or when given a very little bit of fish or a small piece of pork at butchering time.

Edgerton’s brickyards in 1885 provided laborers with two lunch breaks—9 a.m. and 3 p.m.—and served warm meals that usually included hot buttered soda biscuits and coffee. And in a sawmill near Wittenberg in the 1880s, full board was provided.

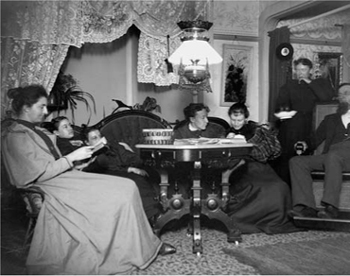

Generally, the boardinghouse was a popular institution in the nineteenth century. According to some estimates, nearly 70 percent of all Americans lived in a boardinghouse at some time in their lives for an average of three years. Such establishments provided living and eating accommodations for the many single men working in towns and cities, for newlyweds or couples or families in the process of arranging permanent living quarters, and for older people in retirement.

Boardinghouses provided companionship along with food and lodging.

WHi Image ID 46048

Whether it was a commercial enterprise run perhaps by a widow, or a private home whose owners were augmenting their meager income, the boardinghouse built its reputation on the skill of the cook. And the quality was extremely diverse. At the low end of the scale was Hans A. Anderson’s poor experience in 1869 in Trempeleau County, where “during the two weeks I stayed there, every meal except one or two consisted of buckwheat cakes and pasty gravy.” The 1849 fare at a boardinghouse in New Holstein was not much better: “Breakfast meant a wholesome meal soup, at noon pap or mush and milk, and evenings more meal soup with cinnamon and milk.” The landlord’s reaction to a complaint about the monotony of this diet was to butcher one of two cows that had helped provide the milk.

Teachers’ Fare

THE CULINARY PLIGHT OF FEMALE TEACHERS in the late 1870s was well illustrated by the remembrances of Melissa Brown, who grew up near Ironton and was later a co-owner of Brown’s Book Store in Madison:

I taught about four miles from my home and boarded with Uncle Jimmy and Aunt Jemina. They charged me $1.25 a week for board, and as I went home Friday evening and came back Sunday afternoon, they deducted for the time I was away, so that my board amounted to 98 cents per week. And the good things I had to eat! Fried chicken, baking powder biscuit—and such biscuit—with honey, and smoked ham and bacon, stand out prominently in my memory. As I was a picture of health and had an appetite to match, you can imagine how much they made “off of me.”

In comparison to this, I remember another boarding place. I think I paid $2.00 a week for board. This family “always boarded the teacher,” so there was no place else to go. They had a farm near the schoolhouse, and were considered quite well to do. Our food for breakfast was always fat salt pork (fried), bread and butter, and coffee. They made the coffee by putting two tablespoons of coffee in a coffee pot, holding at least two gallons, then they would fill it up with water. Consequently the coffee was faint amber in color and tasted like anything but coffee. They kept cows and all kinds of stock, but we never had any cream for coffee, but only very blue milk. All the cream was sold. In the same way the strawberries which they raised were sold. I do not remember that we ever had any to eat. •

In 1837 meals at the first boardinghouse in Beloit were limited after the original ten pounds of flour and six pounds of salt pork gave out. Since lack of money prevented restocking of the larder, the landlord relied on fresh fish, which were easy to come by. Each morning, the flume at the mill was closed and drained, and a generous supply of suckers weighing two to four pounds each was scooped up. The fish not eaten fresh were salted for future use.

Diners’ reaction to boardinghouse food, of course, depended to a great extent on personal tastes. A Blue Mounds visitor living a day or two with a Dutch family in 1850 heartily enjoyed her starchy diet: “I can have as much excellent milk and potatoes as I desire (without spice or fat, and potatoes in this country are my best food), as well as capital butter and bread.”

In many places, there was no choice. Barbara Elmer ran the only public boardinghouse in Black River Falls in the late 1840s, where she fed about thirty men, most of whom were connected with the lumber industry. Salt pork and good, homemade bread was the staple diet, sometimes varied with bean soup and venison.

Later on, more choices became available throughout the state. Hotel dining rooms often offered full board to persons other than hotel guests, and the boardinghouse continued to thrive. Although meals are only rarely included in a salary these days, facilities for buying a reasonably nourishing repast during the working day are provided in many institutions and business establishments.