Country rock incorporated musical elements and songwriting idioms from traditional country music into late 1960s and ’70s rock. Usually pursued in Los Angeles, the style achieved its commercial zenith with the hits of the Eagles, Linda Ronstadt, and many other less consistent performers. Country rock arose from the conviction that the wellspring of rock and roll was the work of 1950s and ’60s regionalists such as Hank Williams, Johnny Cash, and George Jones, as well as, to some extent, that of the Carter Family and Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs and other artists who had blossomed in local folk and bluegrass scenes before the establishment of the Nashville recording industry.

This evolutionary link seemed so essential to groups such as the Byrds and Buffalo Springfield that (perhaps influenced by Bob Dylan’s similarly inclined 1967 album, John Wesley Harding) they sought to import country’s vocabulary and instrumentation into their countercultural pursuit of psychological and formal adventure. Under the sway of Gram Parsons, the Byrds created country rock’s pivotal album, Sweetheart of the Rodeo (1968), the country-purist goals of which seemed somewhat avant-garde in a rock world that had come to disdain all things conceivably old-fashioned. To hear the Byrds perform the Louvin Brothers’ country standard “The Christian Life” was to enter a distanced, highly artistic realm where 1960s counterculture assumptions about the preeminence of loud volume and the obsolescence of tradition were called into question. Because the movement’s very instrumentation—pedal steel guitars, fiddles, mandolins, Dobro guitars, unobtrusive percussion—promoted milder, generally acoustic sonic auras, country rock’s overall effect seemed drastically different.

Significantly, however, the style occurred not in a city alive with the values of contemporary art but in Los Angeles, which during the previous decades had attracted many rural Southerners. Moreover, country rock’s rise to prominence paralleled the rise of the big-budget Hollywood recording studio ethic, the desire to compete with London in the effort to make pop recordings of the most highly advanced sonic clarity and detail then imaginable. Country rock had begun by insisting that the sources—and not the means—of popular music were of signal importance. Yet in the end the movement succeeded by adopting the same exacting production techniques pioneered by the Beatles and their producer George Martin.

It was only a short, exhaustively well-rehearsed and well-recorded step away to the Eagles and Ronstadt (and Asylum Records). Their careers proved central to those of surrounding singer-songwriters such as Jackson Browne, Karla Bonoff, and Warren Zevon, whose simultaneous countryesque confessions creatively fed both the band and the singer. For Ronstadt, country rock progressively gave way to a wide variety of other styles, always approached from the point of view of her American sources, always mounted with the painstaking studio finesse exemplified by producer Peter Asher. For the Eagles, working first with the English producer Glyn Johns and later with Bill Szymczyk, the style became so full-blown that the band’s multimillion-selling album Hotel California (1976) both dramatized the Los Angeles milieu that underpinned the country-Hollywood connection and reflected the growing significance of the symbolism of country rock. Surrounding these careers were a number of other key figures. In addition to founding the influential Flying Burrito Brothers, Parsons introduced former folksinger Emmylou Harris to the music of George Jones, spawning her pursuit of a vernacular vocal art of operatic seriousness and intensity. Neil Young, formerly of Buffalo Springfield, began the traditionalist part of a gnarled, varied body of music that grew into a stylistic cosmos of genius unto itself. Like the Dillards, who came to country rock from a bluegrass background, all three chose not to work as commercially as the Eagles, Ronstadt, or Poco, whose driving force, Richie Furay, was another former member of Buffalo Springfield. Instead they preferred to have their music felt over time in ways less direct and less oriented to mass culture.

‣ Buffalo Springfield, Buffalo Springfield Again (1967)

‣ The Byrds, Sweetheart of the Rodeo (1968)

‣ Bob Dylan, Nashville Skyline (1969)

‣ The Flying Burrito Brothers, The Gilded Palace of Sin (1969)

‣ Neil Young, Harvest (1972)

‣ The Eagles, Desperado (1973)

‣ Gram Parsons, Grievous Angel (1974)

‣ Linda Ronstadt, Heart Like a Wheel (1974)

‣ Emmylou Harris, Pieces of the Sky (1975)

‣ Jason and the Scorchers, Fervor (1983)

By the end of the 1970s, punk and new wave pushed country rock out of the pop charts and the media limelight. The 1980s saw a resurgence of the genre, more geared to rockabilly force than folk and country balladry. Christened “roots rock,” it yielded underground champions such as Nashville’s Jason and the Scorchers, ultimately manifesting itself in the mainstream work of Bruce Springsteen, John Mellencamp, and others. Also by the end of that decade, country music in Nashville had begun to adapt some of the riskier guitar tones and rhythms for its less traditional artists. Elsewhere a new wave of young country rockers, notably Son Volt and Wilco, lumped together under the banner “alternative country” in the 1990s, tried to resurrect the less glitzy side of the movement. But country rock in the most popular sense became a period style, left to evoke the 1970s, a time when artists dressed up deep aesthetic and personal concerns in music that only sounded soft.

The Flying Burrito Brothers were one of the chief influences on the development of country rock in the late 1960s and ’70s. The original members were Chris Hillman (born December 4, 1942, Los Angeles, California, U.S.), “Sneaky” Pete Kleinow (born August 20, 1934, South Bend, Indiana—died January 6, 2007, Petaluma, California), Gram Parsons (born Ingram Cecil Connor III, November 5, 1946, Winter Haven, Florida—died September 19, 1973, Yucca Valley, California), and Chris Ethridge (born 1947, Meridian, Mississippi—died April 23, 2012, Meridian). Later members included Michael Clarke (born June 3, 1944, New York City, New York—died December 19, 1993, Treasure Island, Florida), Bernie Leadon (born July 19, 1947, Minneapolis, Minnesota), and Rick Roberts (born August 31, 1949, Clearwater, Florida).

Parsons, having tasted success earlier in the year as the driving force behind Sweetheart of the Rodeo, and Hillman, another former member of the Byrds, founded the Flying Burrito Brothers in Los Angeles in 1968. They appropriated the name from a group of local musicians who gathered for jam sessions. The Burritos’ first album, The Gilded Palace of Sin (1969), also displayed Parsons’s guiding hand: he contributed most of the songs and shaped its combination of classic country and western—punctuated by Kleinow’s pedal-steel guitar—and hard-driving southern California rock. Even after Parsons left the Burritos in 1970 (replaced by Roberts), his songs continued to appear on the group’s albums, including the live Last of the Red Hot Burritos (1972), which also prominently featured bluegrass musicians. Numerous other personnel changes—including the arrival and departure of Leadon, who helped found the Eagles—and the group’s limited commercial appeal outside a small, devoted following contributed to its dissolution by 1973. Kleinow and Ethridge re-formed the band in 1975, and there were other short-lived incarnations into the 1990s.

Parsons is often called the originator of country rock. Although he disdained that moniker, his work provided the link from straight-ahead country performers such as Merle Haggard to the Eagles, who epitomized 1970s country rock. Numerous performers have cited Parsons as a major influence, notably Emmylou Harris, Elvis Costello, and alternative rocker Evan Dando.

The Dillards took Ozark Mountain style to California and helped lay the groundwork for country rock as well as for a “progressive” style of bluegrass music. The original members were Douglas Dillard (born March 6, 1937, East St. Louis, Illinois, U.S.—died May 16, 2012, Nashville, Tennessee), Rodney Dillard (born May 18, 1942, East St. Louis), Mitchell Jayne (born May 7, 1930, Hammond, Indiana—died August 2, 2010, Columbia, Missouri), and Roy Dean Webb (born March 28, 1937, Independence, Missouri). Significant later members were Paul York (born June 4, 1941, Berkeley, California), Byron Berline (born July 6, 1944, Caldwell, Kansas), and Herb Pederson (born April 27, 1944, Berkeley).

Banjoist Doug Dillard and guitarist Rodney Dillard found early success as performers in south-central Missouri before moving to California. There, against the backdrop of the folk music revival of the early 1960s, they issued three well-received albums that demonstrated their mastery of the rock idiom as well as their deep roots in traditional mountain music. Doug left the Dillards to pursue this country-rock fusion, eventually teaming with Gene Clark, formerly of the Byrds, to form the pioneering country-rock band the Dillard and Clark Expedition. Meanwhile, Rodney took the Dillards in the direction of “progressive bluegrass,” adding drums, pedal steel guitar, and amplified instruments and featuring cover versions of material by contemporary songwriters such as Tim Hardin, Bob Dylan, and the Beatles. The Dillard brothers continued to be a presence in bluegrass and country rock into the 1980s.

The Eagles cultivated country rock as the reigning style and sensibility of white youth in the United States during the 1970s. The original members were Don Henley (born July 22, 1947, Gilmer, Texas, U.S.), Glenn Frey (born November 6, 1948, Detroit, Michigan), Bernie Leadon (born July 19, 1947, Minneapolis, Minnesota), and Randy Meisner (born March 8, 1946, Scottsbluff, Nebraska). Later members included Don Felder (born September 21, 1947, Topanga, California), Joe Walsh (born November 20, 1947, Wichita, Kansas), and Timothy B. Schmit (born October 30, 1947, Sacramento, California).

The Eagles, c. 1970 (from left to right): Bernie Leadon, Don Henley, Glenn Frey, Don Felder, and Randy Meisner. GAB Archive/Redferns/Getty Images

Los Angeles-based professional pop musicians, the Eagles recorded with Linda Ronstadt before the 1972 release of their eponymous debut album. Clearly, from the band’s earliest laid-back grooves on hits such as “Take It Easy” to the title song of their 1973 Desperado album—the “Ave Maria” of 1970s rock—to the later studio intricacies of One of These Nights (1975), Henley’s band felt a mission to portray emotional ups and downs in personal ways. However, the Eagles were content to do so within the boundaries of certain musical forms and music industry conventions, pushing and expanding them gently or aggressively at different junctures along the way. This willingness to play by the rules may have been as responsible for the success of their resolutely formal, exceptionally dramatic songs as was the Eagles’ hankering for the fiddles and dusty ambiences of the country rock movement they polished for popular consumption.

Before the Eagles recorded, country rock was a local alternative in late 1960s Los Angeles. After they recorded, it became the sound track for the lives of millions of 1970s rock kids who, keen on the present yet suspicious of glam rock and disco, donned suede jackets and faded jeans to flirt with the California dream restyled as traditional Americana.

The band’s Hotel California (1976) was, in this respect, their masterpiece. With the craft of songwriting as central to their approach as it is to that of any country singer, the Eagles’ music had begun as well-detailed melodies delivered by Henley and Frey with some nasality. The arrangements, with percussion far more forward than anything Nashville producers would have brooked, started out in a starkly rock mode with rustic accents. By the time they began work on Hotel California, they were joined by ex-James Gang guitarist Walsh, who combined technical expertise with native rambunctiousness. His contribution, mixed with an increasingly assured blend of country directness and Hollywood studio calculation, made for an unmatched country rock–pop fusion that started with One of These Nights and reached its apex with The Long Run (1979). Hotel California, coming at the midpoint of the band’s later period, captured the style at its most relaxed and forceful. Afterward, as punk and new wave repeated country rock’s journey from underground to mainstream, the Eagles’ music subsided.

Beginning in the 1980s, Henley enjoyed a solo career as an increasingly subtle singer-songwriter. As the Eagles had done in the 1970s, he engaged stylistically with his times, staring down electropop on 1984’s moving “Boys of Summer” smash. The Eagles’ music, although never exactly replicated, became the envy of mainstream Nashville artists who longed for some sort of mainstream edge. In 1993 Common Thread: The Songs of the Eagles, a tribute album performed by country artists such as Vince Gill and Travis Tritt, became a blockbuster in that field. The group’s nostalgia-tinged yet still musically vibrant reunion tour and album in 1994 featured four new songs and proved even more successful. In 1998 the Eagles were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

The band reunited again for Long Road Out of Eden (2007), a double album that represented the Eagles’ first collection of completely new material in almost three decades. It was a hit with both critics and fans, and the album also signaled the group’s departure from the traditional industry model of production and distribution. Released on the band’s own Eagles Recording Company label, the North American version of the album was available only through the Eagles’ official Web site and at Wal-Mart stores. In 2009 “I Dreamed There Was No War,” a track from Long Road Out of Eden, won the Grammy Award for best pop instrumental performance.

‣ CHECK OUT ANY TIME YOU LIKE: L.A. IN THE 1970S

Los Angeles had been an important music-business city since the 1930s. The city’s movie industry, the favourable climate, the influx of European émigrés and Southern blacks during World War II, and the founding of Capitol Records in 1942 all contributed to the city’s growth as a music centre. But it was only in the 1970s that Los Angeles took New York City’s place as pop music’s capital. While New York City was troubled by economic collapse and rising crime, encumbered by obsolete studio work practices, and uncomfortable with the studied informality of post-hippie America, Los Angeles crested on California’s new fashionability and economic buoyancy—based in part on the Cold War strength of the aerospace industry. A willingness to abandon the past, an easygoing outlook, the early rumblings of the personal development movement, and a new wave of young entrepreneurs all combined to foster the development of new musical styles.

Taking their cue from the new approach to recording developed by the Beatles while making Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Los Angeles-based musicians reveled in the freedom of creating their music in the studio. This was the heyday of singer-songwriters (many of whom gravitated to Asylum Records), of country rock artists, and of disco (particularly that produced by Casablanca Records). What nearly all of them shared was the belief in the power of positive hedonism, which would dissipate in the early 1980s in response to AIDS and economic recession.

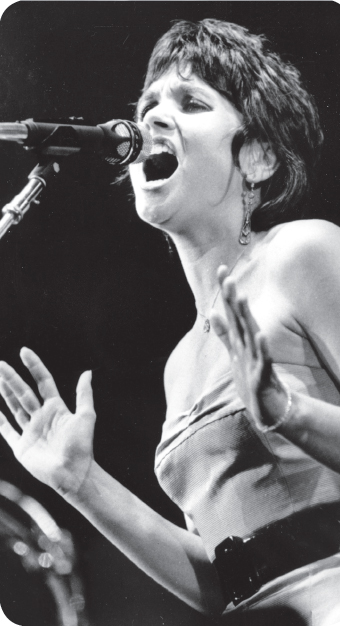

American singer Linda Ronstadt (born July 15, 1946, Tucson, Arizona, U.S.) brought a pure, expressive soprano voice and eclectic artistic tastes to the 1970s music scene. Her performances called attention to a number of new songwriters and helped establish country rock music.

After winning attention with a folk-oriented trio, the Stone Poneys, in California in the mid-1960s, Ronstadt embarked upon a solo career in 1968, introducing material by songwriters such as Neil Young and Jackson Browne and collaborating with top country-oriented rock musicians (including future members of the Eagles). Produced by Briton Peter Asher, Ronstadt’s album Heart Like a Wheel (1974) sold more than a million copies. It also established the formula she would follow on several successful albums, mixing traditional folk songs, covers of rock-and-roll standards, and new material by contemporary songwriters (e.g., Anna McGarrigle, Warren Zevon, and Elvis Costello).

Linda Ronstadt, 1979. © AP Images

In the 1980s and ’90s, with mixed success, Ronstadt branched out. She starred in the Broadway version of the Gilbert and Sullivan musical The Pirates of Penzance (1981–82) as well as the film (1983). Working with big-band arranger Nelson Riddle, she released three albums of popular standards, What’s New (1983), Lush Life (1984), and For Sentimental Reasons (1986). Her two collections of Spanish-language songs, Canciones de mi padre (1987) and Mas canciones (1991), won Grammy Awards, as did her Latin album Frenesí (1992). A long-awaited collaboration with country singers Dolly Parton and Emmylou Harris resulted in Trio (1987), followed by Trio II (1999), which included the Grammy Award-winning single “After the Gold Rush.” Her album of children’s songs, Dedicated to the One I Love, also won a Grammy in 1996.

Poco continued the synthesis of country and southern California rock pioneered by such groups as the Byrds and Buffalo Springfield. The original members were Richie Furay (born May 9, 1944, Yellow Springs, Ohio, U.S.), George Grantham (born November 20, 1947, Cordell, Oklahoma), Randy Meisner (born March 8, 1946, Scottsbluff, Nebraska), Jim Messina (born December 5, 1947, Maywood, California), and Rusty Young (born February 23, 1946, Long Beach, California). Later members included Timothy B. Schmit (born October 30, 1947, Sacramento, California) and Paul Cotton (born February 26, 1943, Los Angeles, California).

The group formed in Los Angeles in mid-1968 around Buffalo Springfield veterans Furay and Messina and originally called itself Pogo; objections from Walt Kelly, creator of the Pogo comic strip, prompted the name change to Poco. Furay, already established as a writer of tender, clear-voiced ballads, added to these a series of exuberant, fast-paced songs that became Poco signature pieces. Messina, an accomplished record producer, contributed his skill for writing catchy, well-crafted songs and his sharp, insightful guitar playing. The addition of Young’s virtuoso work on the pedal steel guitar and Meisner’s clean, high voice were the final elements of the snappy instrumental work and tight multipart vocal harmonies that were showcased on the group’s debut album, Pickin’ Up the Pieces (1969).

A string of critically acclaimed albums followed, notably A Good Feelin’ to Know (1972) and Crazy Eyes (1973). The group maintained considerable stylistic consistency despite numerous personnel changes, including the departures of Meisner (replaced by Schmit), who played with Rick Nelson before helping to found the Eagles, and Messina (replaced by Cotton), who left in 1970 to team with Kenny Loggins for the highly successful duo Loggins and Messina. In 1973 Furay joined in a short-lived collaboration with Chris Hillman and songwriter J.D. Souther, and in 1977 Schmit replaced Meisner in the Eagles. Poco had only modest commercial success throughout its career; Legend (1978) was its top-selling album. A reunion of the original quintet in 1989 yielded the highly regarded Legacy.