In announcing the abolition of the binary divide between universities and colleges, the Green Paper asserted the benefits of larger institutions and used student load to set benchmarks. Two thousand EFTSU were the minimum; 5000 were required for a broad teaching profile and some specialised research activity, 8000 for ‘relatively comprehensive’ research. The small colleges were put on notice to establish ‘arrangements’ with another appropriate institution, and those under the research threshold were advised that they would benefit by joining a university. While the benchmarks were taken from CTEC’s 1986 Review of Efficiency and Effectiveness, Dawkins had looked closely at current enrolment numbers. La Trobe and Macquarie lacked the 8000 EFTSU required for broad research, while Flinders, Griffith and Murdoch were below 5000. If these newer suburban universities were to join with the stronger metropolitan colleges and acquire a broader profile of professional courses, he believed they could challenge the primacy of the older, ossified institutions.1

The Green Paper described this as a process of consolidation but provided little indication of what that meant. It simply observed that ‘multi-campus institutions need not be highly centralised’ and suggested that non-metropolitan colleges might form regional networks.2 That the process would be voluntary was stated from the outset. As shadow Minister for Education, Dawkins had been a leading critic of the mergers imposed by the Fraser government, which between 1981 and 1983 directed thirty-seven smaller colleges into thirteen composite ones, with two others being absorbed into universities. Four colleges that held out against the threat to withhold their funding were reprieved as soon as Labor took office.3 There were certainly inducements for consolidation in the Unified National System: as well as specifying the benchmarks, the Green Paper indicated that capital works, new places and assistance with transitional arrangements would all be directed to compliant institutions. But for the Minister to renege on his earlier stand and prescribe mergers was politically unacceptable, so all institutions were free to seek their partners.

Some were already doing so. When Dawkins took charge, La Trobe and Lincoln Institute of Health Sciences were concluding tortuous negotiations that began six years earlier. The University of Melbourne and the adjoining Melbourne CAE initiated merger discussions following the Minister’s statement in September 1987 and reached agreement early in 1988. The willingness of a university as large and prestigious as Melbourne to incorporate a college had a tonic effect on other universities. Mal Logan of Monash, who was determined to outdo David Penington, had a map of the city on which Monash was to acquire every campus south of the Yarra; in the event he crossed the river to seize the Victorian College of Pharmacy on Melbourne’s doorstep, although he did not complete his southern empire. Some universities and colleges resisted consolidation, but all of them were caught up in the bargaining that followed the Green Paper.4

University historians dealing with this hectic period of aggregation are drawn to the metaphor of courtship. ‘The orchestra plays and the dance begins’, one account opens, and another describes ‘a frenzied dance, partners clasping and diverging and clasping elsewhere, lest they be left neglected or pass into oblivion’. A national study writes of ‘an orgy of courtships and marriages among suitor institutions’, some left at the altar and others condemned to ‘shotgun marriages’.5 The dalliance might begin with a telephone call from a college principal to a vice-chancellor and then a preliminary meeting to consider their mutual attraction. Such trysts could be concurrent, the principal seeking the most attractive consort, the vice-chancellor interested in more than one conquest, and for that reason they were conducted off campus away from prying eyes. John Dawkins used a different figure of speech when he looked back on the flurry of mergers and acquisitions that followed the Green Paper: it was a ‘feeding frenzy’. That description is apt since the initial overtures were often conducted in expensive restaurants, although he had in mind the voracious institutional appetites of particular vice-chancellors, one of whom he likened to a shark and another to a piranha.6

There were no rules to restrain such greed. The White Paper stated simply that proposals for consolidation should be based on educational benefits as well as cost savings; the Commonwealth would consider all proposals on their merits, and they were to be assessed in the first instance by Joint Planning Committees composed of Commonwealth and state representatives. The cooperation of the states was needed since any amalgamation would require new legislation, and all accepted the Unified National System as an opportunity to elevate their colleges. Most went further, undertaking reviews of the state’s current provision and the future needs to press the case for additional student places. Amalgamation policies varied widely. The Labor governments of South Australia, Victoria and Western Australia issued merger guidelines (such as compatibility, contiguity and regional coverage) but were content to canvass multiple options. Terry Metherell, Minister for Education in a new Coalition government of New South Wales, was more prescriptive, nominating the composition of that state’s consolidated institutions. In Queensland, where a National Party government was at loggerheads with Canberra, its minister insisted that all the colleges would be raised to university status.7

Although Dawkins rejected the Queensland plan and dismissed several amalgamations canvassed in the first half of 1988, he withheld any explanation of the criteria for approval. Some general principles were formulated during the preparation of the White Paper—adjacent locations, compatible missions, educational benefits and institutional efficiencies—but the final version used them as arguments to justify the benchmarks rather than as conditions that must be satisfied. The White Paper noted the Minister’s endorsement of some specific mergers and stated that others under discussion would be considered on a ‘case-by-case basis’. It suited his purpose to let the scramble continue while retaining a discretionary power of veto.8

In one jurisdiction Dawkins went further. In July 1988 he summoned the Vice-Chancellor of the Australian National University and the Principal of the Canberra College of Advanced Education to his office and told them that the ACT could support only one institution. Since both were governed by Commonwealth legislation and the ACT was not to begin self-government until the end of the year, this directed merger was difficult to defy. The heavily research-oriented ANU was horrified by the prospect and made its repugnance clear. The prospect of such an unaccommodating neighbour swallowing up a large, enterprising college (which had 4836 EFTSU) alarmed the Australian Committee of Directors and Principals in Advanced Education (ACDP), which warned the Minister that it could set a precedent for cross-sectoral mergers that would sacrifice the colleges’ diversity, innovation and responsiveness to the ‘rigidity and apparent imperviousness’ of universities to any notions of public accountability or community needs. Soon the ACDP and Australian Vice-Chancellors’ Committee (AVCC) were conducting hostilities by press release. In October 1988, when John Scott, chair of the AVCC, appealed to Colin Campbell, his ACDP counterpart, for a truce he warned that the mutual denigration was damaging the public standing of the sector.9

Dawkins failed to impose a merger of ANU and Canberra CAE because the Senate would not pass the legislation needed to enact it. Beyond that setback, the acrimonious public commentary brought a number of other negotiations between universities and colleges to a halt as the ACDP expressed increasing dissatisfaction with merger proposals that ‘appeared to be little more than asset stripping by the large and powerful university interests’. Behind the scenes, Dawkins made it clear that he expected smaller universities to coalesce, and the Federation of Australian University Staff Associations (FAUSA) denounced his ‘brutal and outrageous interference’.10 Publicly, he continued to insist that it was up to the states and the institutions to determine their mergers, that he had no ‘hit list’ and no intention of forcing amalgamation on anyone—but as he realised that people were beginning to take him at his word, he stepped up the pressure. A speech delivered in February 1989 expressed disappointment that the states had not ‘reacted more positively’; as he well knew, they were reluctant to incur the odium of dictating amalgamations. Accordingly, he warned that the Commonwealth needed a speedy resolution of the amalgamation process in order to allocate funds for capital works and provide assistance from the priority reserve fund to assist in the implementation of mergers. He also announced the formation of a special task force to report on the progress to date and suggest how these funds should be allocated.11

Gregor Ramsey chaired the Task Force on Amalgamations, and the other three members were Ian Chubb, a member of the Higher Education Council, Russell Linke, its counsellor, and Paul Hickey, the deputy secretary in charge of the Department’s higher education division; Peter Noonan from the Minister’s office participated to ensure that his intentions were known. By this time it was clear that loose forms of affiliation were not acceptable, and amalgamation required that there be just one governing body, one ‘chief executive’, one educational profile, one funding allocation and one set of academic awards. The task of the emissaries was to apply these rigorous conditions to a wide variety of stalled mergers.12

Over six weeks the task force travelled to almost every institution and held meetings with all the state authorities. New South Wales had largely resolved its consolidation by creating two new universities, and legislation was about to be introduced. In Victoria there were a number of unresolved amalgamations. Queensland continued to insist that it would have seven or eight universities, several of them unacceptable to the Commonwealth. Only one merger was planned in Western Australia, and it was foundering; the same held for two under discussion in South Australia. Tasmania expected to amalgamate all three of its institutions into a single university, and the Northern Territory had already done so with its fledgling university college and institute of technology. Finally, four Catholic colleges in New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland and the ACT were exploring a union that would make them a member of the Unified National System.

This was a mixed report card, although the task force remained optimistic. Perhaps it thought its financial recommendations—money allocated for new buildings to reward merging institutions, along with assistance for amalgamation costs and early retirement schemes—would encourage the laggards. The final report in April 1989 predicted that there would be fewer than forty institutions by the end of the year, all but a very few with more than 5000 EFTSU and most with a broad educational profile. It conceded that some with widely dispersed, multi-campus operations would require a period of transition to integrate their programs and administrative arrangements. Nevertheless, the task force recommended these amalgamations be completed ‘as close as possible to 1 January 1990’.13

Gregor Ramsey and his colleagues must surely have known this was unrealistic. Amalgamations began with a memorandum of understanding, but there was much that needed to be worked out before they were implemented. Lengthy and complex negotiations were required over almost every aspect of the partners’ activities: the composition of the new governing body, the executive officer (more than one merger broke down because both heads expected to become vice-chancellor) and the academic board; the organisational structure and budget system; the academic programs and research policy. Unions had to be consulted on the protection of staff entitlements. It was then necessary to secure the consent of the State Government and arrange for the passage of legislation (several mergers were scuppered by Opposition-controlled upper houses). Queensland submitted to the Commonwealth’s conditions in mid-1989 but did not effect its new arrangements until the following year. The failure of the mergers mooted in South Australia meant that its principal amalgamation began in 1991. In Victoria and elsewhere, smaller, specialised colleges were still being taken into universities in 1992.

The benchmark requirements for membership of the Unified National System created a fundamental asymmetry in negotiations. Large universities with more than 8000 EFTSU did not need to participate since they could maintain their existing range of teaching and research without any expansion. Most colleges had a strong inducement to do so in order to become eligible for research, and the very survival of smaller colleges was at stake. No university merged with another university, so that there were only two kinds of amalgamations: those that occurred within the college sector and those that attached colleges to universities. Sixteen universities were involved in such ‘cross-sectoral’ mergers, and not one of them felt the need to change its name.

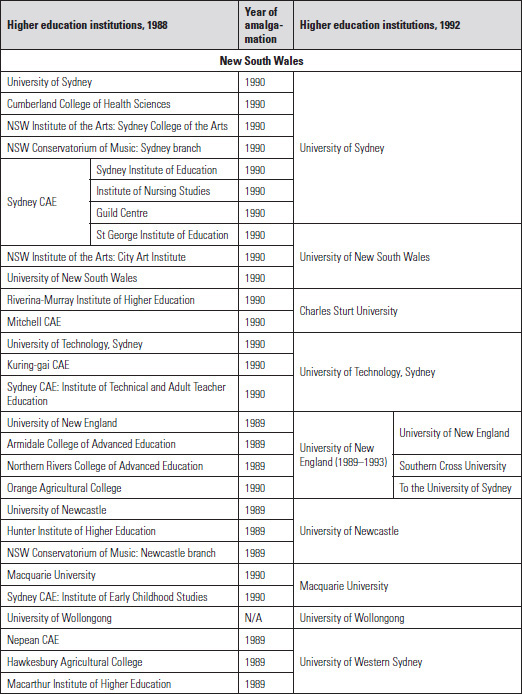

Table 2: Amalgamations in Australian higher education, 1988–92

The older, more prestigious universities enjoyed the greatest freedom of manoeuvre since they were partners of preference, and several took advantage of the consolidation process to make numerous acquisitions. Monash absorbed the large Chisholm Institute of Technology (with campuses in Caulfield and Frankston), the regional Gippsland Institute of Advanced Education with its strong distance education program, the Administrative Staff College at Mount Martha and the small but prestigious Victorian College of Pharmacy. It missed out on some other colleges but emerged as the largest university in Australia. Melbourne followed its merger with Melbourne CAE by taking in a small institute of technical education, the Victorian College of the Arts and the multi-campus Victorian College of Agriculture and Horticulture. (It also assisted Ballarat CAE to maintain independence through temporary status as an affiliated university college.) In New South Wales the University of Sydney acquired most of Sydney CAE, a college of health sciences, the Sydney College of the Arts and the New South Wales Conservatorium of Music. It too would subsequently add an agricultural college.14

Other strong universities held aloof. The Vice-Chancellor of the University of New South Wales was prepared to accept Terry Metherell’s plan, which would have placed it at the centre of a large network of regional colleges, but his Chancellor overruled the arrangement so it appended just a small metropolitan institute of education and an arts institute. The University of Western Australia proceeded some way towards a merger with Murdoch but went cold and annexed only an adjacent campus of the Western Australian CAE. Adelaide was close to an amalgamation with the South Australian CAE but again baulked and took in just an adjoining campus of the college in North Terrace and Roseworthy Agricultural College. And the University of Queensland showed a conspicuous lack of interest, accepting only that state’s agricultural college.15

Brian Wilson, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Queensland, gave a succinct explanation of his reluctance to expand: ‘the University would not compromise the quality of its own teaching and research programs by spreading resources ever more thinly’.16 The enlargement of Monash, Sydney and to a lesser extent Melbourne came at considerable cost. They assumed responsibility for institutions that were less generously funded, awards that were less prestigious and staff with limited research experience. The dilution of research performance was not the only adverse consequence. The bedding down of mergers, rationalisation of courses and integration of administrative systems was burdensome. The early retirement and voluntary redundancy schemes were damaging for staff morale. Multi-campus operations proved vexatious and unwieldy.

Why did three leading universities take this path? One reason was that they had remained stagnant over the preceding decade of the steady state and saw mergers and acquisitions as the only way to regain momentum. A more proximate consideration was their location in the two most populous states with the greatest number of higher education providers. After the Green and White Papers signalled a more competitive environment, they made a strategic decision to safeguard their primacy by growth and diversification. Prestige and drawing power enabled them to determine their acquisitions, and for the most part they chose colleges offering professional courses that would give them a competitive edge in numbers and profile. These conditions did not hold in the less populous states where the options were fewer and the competition less keen, and the established universities of Adelaide, Queensland and Western Australia felt confident in resisting agglomeration.17

The response of the other metropolitan universities is consistent with this explanation. With the exception of the University of New South Wales, they had stronger incentives to bolster their size and standing, but a more restricted choice. Macquarie coveted the colleges to the north and west of Sydney but was thwarted by Metherell’s determination to turn them into a new university; it hoped to acquire two campuses of Sydney CAE, but only Dawkins’ intervention secured it an institute of early childhood studies. In Victoria, La Trobe did not proceed to amalgamation with the nearby Phillip Institute of Technology and obtained just Bendigo CAE and a tiny operation at Wodonga. Geelong-based Deakin failed in a bid to build a network of regional colleges and won only the Warrnambool Institute of Advanced Education; but Deakin hit the jackpot when the large Victoria College in Melbourne’s eastern suburbs decided that it was more congenial than Monash. Elsewhere, Griffith benefited from the University of Queensland’s inactivity. It first absorbed a campus of Brisbane CAE and then gained Gold Coast CAE, Queensland Conservatorium of Music and the College of Art. The University of Tasmania’s amalgamation with the Launceston-based Institute of Technology was dictated by benchmark requirements, but Flinders made do with an adjacent section of the South Australian CAE, and Murdoch staff vigorously resisted a merger with the Western Australian CAE.18

Apart from Deakin University in Geelong, there were only four regional universities in 1988: James Cook at Townsville in northern Queensland, New England in the northern tablelands of New South Wales and Newcastle and Wollongong on the state’s coast. James Cook had fewer than 4000 EFTSU but was sacrosanct; Newcastle absorbed the neighbouring Institute of Higher Education and a local branch of the state’s conservatorium of music, and Wollongong had merged previously with the CAE there. New England was the most anxious and joined with the local Armidale CAE, the fast-growing Northern Rivers CAE based 350 kilometres away at Lismore, and the agricultural college at Orange. The problems of this merger, the only one to fall apart, receive closer examination below.

The metropolitan institutes of technology, with their industry links, professional courses and growing research base, were best placed to maintain independence. The Western Australian one had already been turned into Curtin University of Technology, as had the New South Wales Institute of Technology, now the University of Technology, Sydney, to which a medium-sized college of advanced education was added. The Queensland Institute of Technology took in nearly all of Brisbane CAE to become the Queensland University of Technology, and the University of South Australia was created by a merger of the South Australian Institute of Technology with the South Australian CAE. In Victoria, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology absorbed Phillip Institute. That left Footscray Institute of Technology in the cold, and it combined with the new Western Institute to become the Victoria University of Technology, while on the other side of the city Swinburne Institute preferred to stand alone as Swinburne University of Technology.19

The most vulnerable colleges were the large, multi-campus, metropolitan CAEs created in the last round of amalgamations less than a decade earlier. Except for Canberra CAE, the only one to escape annexation was the Western Australian CAE, and that was because no one wanted it. Canberra CAE’s redesignation as the University of Canberra required a period of sponsorship by an established university, a condition imposed on the Australian Catholic University and several other new universities. These included Charles Sturt University, formed from Mitchell CAE at Bathurst and Riverina-Murray Institute of Higher Education at Wagga Wagga and Albury; the University of Southern Queensland, formerly Darling Downs Institute of Advanced Education, and Central Queensland University, which had been Capricornia Institute.20

With Curtin and the University of Technology, Sydney, there were twenty-one universities in 1988. Including the four Catholic institutions, there were fifty colleges. The universities feasted on all or part of thirty colleges, while fifteen new members of the Unified National System were formed from the remnants. The broad pattern is clear: the principal institutes of technology remained intact, the large metropolitan colleges crumbled, the smaller specialised ones were absorbed and distance afforded some protection to regional colleges.21

Since mergers were conditional on mutual consent, the outcomes were strongly influenced by institutional decision-making. Vice-chancellors made the running. One condition of membership of the Unified National System was that they should have the powers of a chief executive officer, and it was in negotiating mergers that many flexed their enhanced authority. But not all prevailed. The Chancellor crystallised a widespread concern about the Vice-Chancellor’s plan to enlarge the University of New South Wales. Opposition from the university staff associations derailed amalgamations negotiated by the heads of Adelaide and Flinders universities, while professorial resistance stopped other vice-chancellors from proceeding with theirs. College heads were less troubled by internal dissent, but the principals of some regional ones were constrained by local power-brokers adamant that the region must retain control of its own institution. A merger of a large university with a small metropolitan college was usually a fait accompli, but it was more difficult for evenly matched parties to reach a workable agreement. These variations are best appreciated by turning to some specific examples.

Regional and rural institutions faced perhaps the greatest challenge in meeting the conditions of membership of the Unified National System. Many fell short of the 2000 EFTSU minimum benchmark, but they faced the hurdle of being located far from potential partners. The closest options, furthermore, were not always desirable or suitable matches. Some allied themselves with a metropolitan university: the Queensland Agricultural College in Gatton joined the University of Queensland, its South Australian counterpart in Roseworthy became a campus of the University of Adelaide, and the conglomerate Victorian College of Agriculture and Horticulture defied State Government plans to carve it up and merged with the University of Melbourne.22 Others, however, formed regional groupings through a mixture of choice and political pressure. There were two such arrangements in New South Wales, and the success of Charles Sturt University contrasted with the failure of the University of New England.

Riverina-Murray Institute of Higher Education, with campuses in Albury and Wagga Wagga, and Mitchell CAE in Bathurst were the main providers of higher education in southern and south-western New South Wales, having evolved from their origins as agricultural and teachers colleges. Neither was small: Mitchell had 3514 EFTSU and Riverina-Murray Institute 3949, although only about 500 from the latter studied at its Albury campus. The State Government wanted them to be attached to the University of New South Wales as part of a large state university based on the Californian model, and when that proposal was abandoned the metropolitan university suggested that they become colleges under its existing Act. This proposal was unattractive to the two colleges, which instead explored a merger that was to include the specialist Orange Agricultural College (476 EFTSU) to form a rural university, with the University of New South Wales acting as sponsor. After vigorous lobbying, the State Government gave support in early April 1989, as did the Ramsey task force. Orange Agricultural College, however, had other ideas. Its delegates sensed little sympathy at Bathurst for its mission and declined to participate.23

The passage of state legislation on 2 June 1989 formalised the amalgamation of Mitchell and Riverina-Murray as Charles Sturt University—the name honours the explorer who surveyed the three rivers on which the three foundation campuses were situated. As with the statutes that established the University of Western Sydney and enlarged the University of New England, the Charles Sturt University Act created what was called a federated network university. Although it did not define the concept, the federated network allowed a compromise between the wish of constituents to maintain autonomy while meeting the Unified National System requirements of one vice-chancellor, one governing body and one educational profile. Each network member had a chief executive for its daily operation with a large measure of control over the budget.

Supporters and critics alike credit the foundation Vice-Chancellor Cliff Blake with bedding down this new regional university. Before his appointment in early 1990, an interim board of governors had to make significant decisions, including a secret ballot that located the University’s headquarters in Bathurst. Blake had been the principal of Riverina-Murray Institute at Wagga Wagga, so his selection helped balance regional rivalries.24 But he also brought a highly personal and directive style of leadership quite different from the collegial practices of Mitchell CAE—giving rise to allegations of ‘Waggaisation’ as he moved quickly away from the federal model. Under the ‘integrated but decentralised’ structure that he introduced, budgets were allocated to divisions and faculties rather than campuses, and courses were taught across the campuses; video conference facilities and a fleet of cars facilitated this arrangement. Blake took advantage of vacancies in the posts of campus principal to turn them into deputy and pro vice-chancellors, each with university-wide duties.25

The Vice-Chancellor of Charles Sturt was an innovator rather than a consolidator, quick to seize opportunities (so that the university became the country’s leading provider of police training) and transcend the regional role while preserving the bush ethos of the agricultural college. Cliff Blake’s reluctance to delegate was legendary. He chaired almost every selection committee, personally vetted applications for study leave and claims for travel expenses. By his own admission he was an ‘optimistic enthusiast’ who could not cope with people who told him their glass was half-empty. Significant decisions, including those on the university’s identity, structure, research and teaching programs, were made at senior levels with limited consultation, and some academics found this top-down process to be alienating and authoritarian.26 For all the geographic decentralisation involved in Blake’s model, his ebullient personality welded the new university together, and in 1995 it moved to expunge the term ‘network’ from its statute.

The network University of New England, on the other hand, failed. While other amalgamations were scuttled at advanced stages, this was the only one to be dissolved. Initially it seemed to have more favourable prospects than Charles Sturt, for it involved a respected university with an established research record, and was certainly judged more attractive by Orange Agricultural College, which threw in its lot with the distant northern network. Located in Armidale, the University of New England had a proud history as Australia’s first regional university but, with just 5846 EFTSU and limited local population growth, feared the new universities in Sydney would drain its enrolment. Even with the addition of Armidale CAE (1390 EFTSU), it fell short of the student numbers stipulated for a comprehensive research mission. Accordingly, the University reached agreement with Northern Rivers CAE (1931 EFTSU) in Lismore, a five-hour drive away. Negotiations with these two colleges were concluded in August 1988. Orange, which was seven hours to the south, joined at the beginning of 1990, and a new campus of the University at Coffs Harbour, less than three hours away, became the network’s final member in 1991.27

Even as the University and the first two colleges agreed to amalgamate, there were tensions. Armidale CAE, while resigned to its lot, resented the patronising superiority of the establishment on the other side of town and therefore welcomed the inclusion of Northern Rivers CAE. Northern Rivers was less submissive. Rod Treyvaud, the thrusting principal, had raised eyebrows with his involvement of the College in the dubious scheme for a private Cape Byron International Academy; he aspired to university status, but not at the expense of independence. Accordingly, Treyvaud wanted the new entity to be designated the University of Northern New South Wales, a change that was unacceptable to the governing body of the University of New England. The senior staff at Armidale publicly questioned Northern Rivers CAE’s academic standards, while the College’s officers did the same about the University’s financial management.

The state’s decision to enshrine the federated network principle in the 1989 legislation establishing the new university fanned the flames. Treyvaud canvassed state and federal politicians to press his case for maximum devolution even as the Armidale institutions worked towards integration. The structure of the new university encouraged dissent. Each of the campuses had its own principal and ‘advisory council’, which in Lismore went far beyond an advisory role in backing Treyvaud’s intransigence. Armidale wound up its Academic Board upon the formation of a university-wide Academic Senate, but the other components retained academic boards and used them to extend their own courses—soon there were two separate legal programs. Arrangements at Armidale compounded the discord. The Vice-Chancellor was based there (and, with unfortunate symbolism, continued to occupy the same building) but remained aloof from the mounting disquiet since a separate Armidale principal ran that campus. One academic critic described the network head office as ‘the new Kremlin on the hill’.28

Changes of leadership created additional problems. The Vice-Chancellor of New England who initiated the amalgamations, Laurie Nichol, resigned at the end of 1987 to take charge of ANU. His successor, Don McNicol, encountered mounting opposition before he too departed in 1989 to become Vice-Chancellor of the University of Sydney. His replacement was Bob Smith, formerly the chair of NBEET, who devolved further power to campus heads—a decision quite unlike Cliff Blake’s centralisation of management at Charles Sturt.29 This fostered further rivalry between Armidale and Lismore, especially over the allocation of Commonwealth funds. When the Department’s new relative funding model reduced the operating grant for 1991, Smith decided that the University should follow it and reallocated funds from Armidale to Lismore. As staff at the old university, who earned most of the research income, expostulated about it ‘being bled dry by its vampire sister campus’, they demanded restoration of their own academic board and used it to declare their preference for separation.30

In 1992 the Commonwealth and state ministers asked Michael Birt, the outgoing Vice-Chancellor of the University of New South Wales, to chair an advisory group and propose a solution. He decided that the two campuses at Lismore and Coffs Harbour should incorporate some other learning centres east of the Great Diving Range and become a university in its own right. Legislation to create Southern Cross University was enacted in the following year. Armidale retained the University of New England name, along with the local college, and returned to a unitary structure. Orange, for its part, joined the University of Sydney.

A range of reasons has been advanced to explain the collapse of the University of New England network. Grant Harman, an expert on higher education policy who was based at Armidale and chaired the network university’s Academic Senate for most of its existence, identified five contributory factors: Armidale and Lismore were unsuitable partners with quite different values and a conspicuous lack of mutual respect; they lost motivation for the merger as its imperative faded; there were structural and legislative weaknesses; geographical difficulties bedevilled communication and distribution of resources; and the disloyalty of key players compounded ineffective management.31 The first explanation has a superficial appeal, but it cannot account for why other culturally distinct institutions amalgamated successfully, as exemplified by Charles Sturt. Lynn Meek, another leading scholar of higher education who was also at Armidale, explored complaints by staff who felt disrespected or unwanted, but these were neither unique to New England nor more venomous than elsewhere. The petty public sniping between partners, the disagreements over educational missions and academic standards, and the debate over whether to appoint college staff to professorial ranks all occurred in other mergers. An amalgamation without any of these qualities was a rarity; a good number evinced all three. When combined with Harman’s other explanations, however, the personal tension becomes more potent.32

The original university, once it combined with Armidale CAE, required only modest student growth to reach 8000 EFTSU. When it became clear that this threshold would not be enforced strictly, Lismore—which was enjoying strong growth—realised that it too could stand alone. Hence the incentives for merger lost their appeal, and some responsibility must lie with the Commonwealth. Geography was no insurmountable barrier since other institutions managed scattered networks of campuses, but New England’s devolved structure enabled two evenly matched adversaries to pursue parochial campaigns for full independence.

Harman’s argument about disloyalty echoes that of Susan Bambrick, foundation director of New England’s Coffs Harbour Centre. In her view, the process fell apart because positions of authority were filled by ‘strong, ambitious and uncompromising personalities’ when the network required ‘tolerance, cooperation, unselfishness, and a long-term view’ to work.33 Here the cultural and motivational explanations combine with the potential for regional interests to exploit structural weaknesses. The pursuit of short-term advantages by campus heads and other senior figures proved fatal. Without a strong centre to mediate these rivalries, the network’s demise was a matter of time.

The difficulties of a third federated university shed further light on divergent fortunes of these two regional ones. The University of Western Sydney was formed in 1989 from Nepean CAE (3370 EFTSU), Hawkesbury Agricultural College (1781) and Macarthur Institute of Higher Education (2996) after Canberra blocked a proposal to create a new Chifley University on grounds of cost. The campuses, stretching from Parramatta to Richmond in the north-west, Liverpool to Campbelltown in the south-west, were separated less by distance than by rivalry. Each member had its own chief executive, budget, administration and academic committee—practically every senior position was triplicated. They competed for resources, enrolments (there were three separate stands at an international recruitment fair in Asia) and the opening of additional campuses. The IT systems remained incompatible and, as relations deteriorated, they even stopped lending each other books from their libraries. A quality assessment committee that visited the University in 1994 found that ‘the members operate in most regards as separate institutions’. Nepean was the most fractious, cultivating community and political support for secession while rejecting the Vice-Chancellor’s request to attend a faculty meeting. But this mutiny was quelled by the refusal of the state and federal ministers to entertain separation. Harman’s list of reasons for a failed amalgamation has to be supplemented by a countervailing factor: government resolve.34

If New South Wales’ network model stored up problems for the amalgamated institution to resolve, more conventional mergers were likely to encounter them at the point of formation. In 1988 South Australia had five higher education institutions: two universities, Adelaide (7666 EFTSU) and Flinders (4922); two multi-campus colleges, the South Australian CAE (8492) and South Australian Institute of Technology (5562); and an agricultural college at Roseworthy (546). The CAE, formed from previous rounds of amalgamation, and the Institute of Technology both aspired to university status.35 The State Government moderated their aspirations when the Office of Tertiary Education came down in favour of a two-university model in July 1988. It proposed that Flinders absorb the Institute and two campuses of the college, while Roseworthy and the rest of the College would go to Adelaide. Each university under this plan would have a central city presence, suburban campuses with potential for growth, and distinctive fields of specialisation.36

After the state outlined its plan, the institutions were left to arrange the details among themselves, and from this convoluted process the University of South Australia emerged. There was no prescriptive hand, as in New South Wales. Both the Institute of Technology and Flinders wished to preserve their independence, but Gregor Ramsey—whose career began in South Australia—visited from Canberra to make it clear that failure to participate in the formation of larger institutions would jeopardise their Commonwealth funding. Merger discussions between the two began in March 1989, with a view to amalgamation by January 1990. The next month, the report of the task force chaired by Ramsey favoured proposals not dissimilar from that of the Office of Tertiary Education, with particularly strong support for amalgamation of Flinders and the Institute.37

Their negotiations foundered, however, when faced with vexing questions about how the new university would be funded in its early years. The usual concerns of university staff about the academic standards of their college counterparts were exacerbated by the prospect of money flowing from Flinders to the Institute. With the leaders of both institutions determined to lead the new university, the Flinders vice-chancellor bowed to opposition from the Flinders Staff Association and abandoned the merger in July 1989. The University of Adelaide and the South Australian CAE, meanwhile, also tentatively explored their options together. The College was hostile to any suggestion that it be split up and its equal opportunity provisions ran well ahead of those at the University, while academics at Adelaide were concerned about the maintenance of collegiality, standards and funding. Discussions ceased abruptly in July when Adelaide’s vice-chancellor lost his nerve and backed away from a merger.38

By August 1989, therefore, the only South Australian institution to find a partner was Roseworthy, which was well down the path to joining Adelaide. With the state’s two-university model in tatters, the other four had to return to the drawing board. In contrast to the problems of distance and limited options that hobbled rural amalgamations, irreconcilable objectives and opposing interests among larger, more diverse participants complicated metropolitan negotiations. If the academics at Armidale eventually rose up in rebellion against a merger arranged by the Vice-Chancellor, those at Flinders and Adelaide prevented theirs from proceeding to one.

Multi-campus colleges did not enjoy such freedom of choice. They resented Canberra’s demands, hoping to maintain unity and not suffer another round of break-ups and mergers, but the demands proved too great to resist. The South Australian Institute and CAE found themselves drawn together since the State Government would not erect both as universities. The structure emerged by the end of 1989: the College’s Magill, Salisbury and Underdale campuses would merge with the Institute, while its City campus would go to Adelaide and the Bedford Park one to Flinders. Crucially, Robert Segall, the College principal and bitter opponent of breaking up his institution, was on leave; the acting principal, Denise Bradley, was an NBEET member and acutely aware of the realities of Commonwealth funding. Some schools within the Institute, more attracted to the status from merging with Adelaide, resisted the amalgamation, but both governing bodies and the State Government were supportive.

Hence the University of South Australia emerged on 1 January 1991 as the state’s largest university with 12 808 EFTSU. There was a conscious effort to integrate two entities markedly different in their missions and values and, in contrast to the top-down process followed at New England, to involve staff through forums and broadly constituted working parties.39 The University of South Australia was also able to build on strengths in fields of technology and social professions not covered by Adelaide and Flinders. Largely as the result of the obduracy of their academic staff, these universities were left with modest acquisitions. Adelaide, with inherited prestige and a strong research record, felt confident in its primacy. Flinders, which still fell more than 1300 EFTSU short of the 8000 threshold, suffered from the lack of a city presence and limited range of professional programs. The advantages it had enjoyed in an earlier period of bold experimentation were spent. Flinders would struggle.

The difficulties in South Australia are thrown into relief by the failure of amalgamation proposals in Western Australia. This state had just four institutions of higher education, the original University of Western Australia (8741 EFTSU), the subsequent and smaller Murdoch University (3431), Curtin University (10 578)—formerly the Western Australian Institute and a cuckoo thrust into the university nest from the beginning of 1987—and the Western Australian CAE (8892), a sprawling network of five campuses in Perth and a sixth in Bunbury. Curtin had no need to amalgamate and no desire to do so. Dawkins encouraged the CAE to amalgamate with Murdoch, but Douglas Jecks, its single-minded director, was adamant that his institution be left intact and upgraded to university status. He found support from Carmen Lawrence, the state Minister of Education, who personally chaired a review of higher education in Western Australia, so that the College was raised to university status as Edith Cowan University in 1991.40

That left only the two established universities in play. Since the University of Western Australia had led the planning of Murdoch University (which was originally to be its overflow campus) and provided many of the foundation appointments, this might seem an obvious partnership; but the younger university struck out with a brash irreverence that offended traditionalists at the older one. With the steady state imposed so soon after its creation and keen competition from the resourceful Curtin University, Murdoch struggled to attract students. A joint working party achieved heads of agreement for a closer relationship with the University of Western Australia, but there was little enthusiasm there, and after Bob Smith, the Vice-Chancellor, departed for Canberra in July 1988 to chair NBEET, its Senate imposed new conditions. Peter Boyce, the Murdoch Vice-Chancellor, was facing strong resistance from his own Senate and implored Dawkins to apply pressure to the unwilling suitor.41

Dawkins had little sympathy with Murdoch. In keeping with his expectation that smaller universities should combine with colleges, he had previously urged it to merge with the Western Australian CAE and evidently blamed Murdoch for that not happening. Now he and Gregor Ramsey made clear the penalties it would suffer if it did not throw in its lot with the senior university. Such blatant transgression of the assurance that Canberra would not dictate amalgamations brought condemnation of ‘Destroyer Dawkins’ from the Liberal Party and Carmen Lawrence insisted that any merger would be conditional on mutual consent, so negotiations resumed and proceeded at weary length through 1989. The larger university holding the whip hand, it prescribed even more onerous conditions: the new entity would retain the title of the University of Western Australia with a unified structure and the integration of Murdoch’s interdisciplinary programs into its departmental structure. And since Boyce judged that there was no alternative to what he conceded was an ‘unconditional surrender’, Lawrence was able to introduce the enabling legislation into the state parliament at the end of the year.42

By this time, however, the treatment of Murdoch was a subject of public controversy in a state always sensitive to slights from the Commonwealth. In September, the former premier Sir Charles Court stated that there were ‘bigger and nobler issues’ for the future university system than ‘some dollars and administrative convenience for today’.43 Since he had saved Murdoch from a similar fate at the hands of the Fraser government a decade earlier, this could not be passed off as mere partisan rancour. Moreover, Hendy Cowan, leader of the National Party, which in Western Australia was not part of a Coalition partnership, had been a persistent opponent of Murdoch’s forced amalgamation. He and the other two National members of the Legislative Council joined the Liberals on Christmas Eve to defeat the legislation.

This caused no grief at the University of Western Australia. The professor in the Arts Faculty who told a meeting of staff there that ‘Murdoch is sinking and UWA is providing the lifeboat’ captured the prevalent attitude.44 Such grudging assistance was motivated less by compassion than concern that the stricken vessel might be taken in tow by a rival, for Curtin had expressed interest in its acquisition. Now Murdoch proceeded alone. The threatened penalties did not eventuate, but neither did Canberra do it in any favours. Like Flinders, Murdoch was a suburban university with a limited range of courses struggling to keep up with larger, more favoured competitors.

Murdoch’s contemporary, Griffith University, provides a striking contrast. In size, character and mission these two last blooms of the crop of new universities were remarkably similar. Both began teaching in 1975 on handsome campuses in bush settings on the outskirts of their respective cities, using an interdisciplinary structure and an innovative curriculum that included Asian, environmental and women’s studies. Griffith enjoyed stronger growth but, with just 4200 EFTSU in 1988, remained vulnerable—indeed, the two universities were singled out in an editorial of The Australian in 1986 as lacking the size, breadth and depth to ‘justify the description of a university’. Griffith also began as a second campus of its city’s original university, but there was no enthusiasm at the University of Queensland (14 807 EFTSU) for a closer relationship. Queensland Institute of Technology (7305) was intent on elevation to university status, leaving Brisbane CAE (7518) as the most likely partner.45

The amalgamation process in Queensland was unlike any other. For nearly two decades Joh Bjelke-Petersen, a homespun despot who had little time for universities and even less for Canberra, had run the state. Having succumbed to hubris and launched an unsuccessful campaign to win the 1987 federal election, he was caught up in a royal commission established by the interim premier to investigate allegations of corruption and overthrown in a party room vote at the end of the year. Brian Littleproud, who became Minister for Education in a National Party administration in its death throes, kept up the parochial tradition with constant criticism of Dawkins and his proposals. Dismissing the Commonwealth’s amalgamation guidelines, he devised a unilateral process to raise all Queensland’s colleges to university status on the basis of reports that he refused to share with the Commonwealth. These included two regional colleges, Darling Downs Institute of Advanced Education (4770 EFTSU) at Toowoomba, which eventually became the University of Southern Queensland, and Capricornia Institute (2707) with its main campus at Rockhampton, which became Central Queensland University.

That left a number of colleges in or around Brisbane: Brisbane CAE, Queensland Conservatorium of Music (317 EFTSU), Queensland Agricultural College at Gatton (1442) and a new CAE on the Gold Coast (351). Littleproud proposed that they join Griffith to form a federated University of South East Queensland. Griffith was interested in all of them but not on those terms, and none wished to join such a conglomerate. In any case, Dawkins had no intention of allowing the Queensland government to redesignate its colleges as universities without proper consultation, and his threat to withhold funding brought Littleproud’s capitulation in June 1989.46

In ensuing negotiations the Agricultural College chose the University of Queensland and most of Brisbane CAE merged with the Queensland University of Technology, but Griffith acquired the CAE’s Mount Gravatt campus close by its own campus at Nathan, as well as the Conservatorium and Queensland College of Art (raised from TAFE status). Above all, with the support of DEET it was successful in a bid for Gold Coast CAE. This turned out to be the most valuable acquisition since it extended the university’s catchment along the Brisbane–Gold Coast corridor. Griffith, like Flinders and Murdoch, was situated to the south of the city, but in its case that location enabled it to capture population growth, while the smaller colleges of music and art gave it a central presence. The amalgamations increased the student load to 11 182 EFTSU in 1991 and additional Commonwealth and state-funded places lifted Griffith to 15 948 by 1996.47

The Vice-Chancellor, Roy Webb, had to walk a fine line in negotiating the amalgamations. Many at Griffith, including the Chancellor, feared it would be swamped by the inclusion of colleges to the detriment of its distinctive academic ethos. If Mount Gravatt, the Conservatorium and the College of Art preferred joining Griffith to any available alternative, they were determined to protect their particular missions, and Gold Coast CAE continued to campaign vigorously for independence. Webb acknowledged these concerns with a college structure that gave each new campus a director and advisory council; he tried to placate the Gold Coast with representation on the University Council and a one-line budget. With growth came a wide range of new professional programs—in business, law, education, health sciences and leisure studies—along with greater integration of administration, course structures and staff procedures. The common foundation year that had distinguished Griffith from older universities disappeared, the interdisciplinary schools became more conventional and the original divisions were replaced by faculties.

Roy Webb had come to Griffith as an outsider in 1985, and when he retired in 2002 he was the longest-serving vice-chancellor of an Australian university. From the beginning he was intent on growth. The abolition of the binary system and the good favour of the Commonwealth enabled him to achieve it. There were acute growing pains in this enlargement, most evident in the backlog of building projects needed to keep up with larger classes and increased research, but the upward trajectory of the multi-campus Griffith University held its components together.

The Green and White Papers spoke of fewer and larger institutions in Australia’s Unified National System of higher education, but did not insist they must all be universities. That title was for the states to confer, and so long as an institution offered an appropriate range of graduate and postgraduate programs in at least three major fields of study, the Commonwealth had no objection. In practice all fifteen members of the Unified National System that came from the college sector called themselves universities; even Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, which did not want to give up its identity, adopted the title of RMIT University.

The established universities were reluctant to accept such indiscriminate bestowal of their exclusive designation. Late in 1987, when the AVCC was considering whether to accept Curtin University as a member, it set out the characteristics of a university: among the expectations were a range of academic programs of an appropriate standard and a demonstrated capacity for research. Then, as the amalgamation negotiations gathered pace, the university heads formulated more precise criteria. There should be enrolments of at least 500 EFTSU in at least three major fields (such as science, engineering or education). At least 3 per cent of the students were to be engaged in postgraduate research; 25 per cent of the staff would hold doctoral qualifications; they should produce at least one refereed publication every two years, and one in twenty should hold a competitive research grant. These guidelines were provided to the Task Force on Amalgamations, which endorsed them as ‘valid and essential characteristics’ and employed them in evaluating specific proposals.48

The AVCC went further in a statement, The Nature of a University, released shortly after the task force’s report. In addition to the threshold indicators for acceptance as a university, it now specified more demanding ones for the profile of a ‘well-established university’: 500 EFTSU in four or more fields, 7 per cent in postgraduate research, three grants for every twenty academics, 60 to 80 per cent of whom would hold doctorates and who were to produce two to five publications a year. This was gilding the lily. Older universities exceeded the research higher-degree load, but not the more recent ones. None met the publication standard, and only the laboratory disciplines came close to the quota for competitive research grants. Most university staff held doctoral qualifications, although not in professional fields such as architecture and economics, and across the universities—all of which had been operating for more than a decade—the figure was below 70 per cent.49

By distinguishing a ‘well-established university’ with such inflated standards from an aspirant one, the AVCC sought to control admission to university status. It was prepared to admit new ‘associate’ members from the college sector. Following a favourable report from an AVCC ‘visiting committee’ on the newcomer’s plans for improvement, it could then be designated a ‘recognised university’ with full voting rights. Only some colleges submitted themselves to this indignity, which the ACDP denounced. Such gate-keeping was in any case a forlorn endeavour, for once a college was admitted to the Unified National System, it enjoyed all the entitlements of a university, and once the State Government bestowed the title it could style itself one regardless of AVCC recognition. If the peak body was to represent the enlarged sector, it had no alternative but to admit any director or principal who acquired the title of vice-chancellor.50

Bowing to reality, the AVCC decided at the end of 1989 to open its ranks to all members of the Unified National System. As colleges metamorphosed into universities they took advantage of this opportunity, so that the ACDP became a rump organisation representing the dwindling number of colleges still awaiting redesignation or amalgamation until it was absorbed into the AVCC at the end of 1990. Even then the effects of the binary divide lingered in a commonly used distinction between pre-1987 and post-1987 universities, 1987 being the year in which Curtin University of Technology came formally into existence.

It was hardly surprising that research should figure so prominently in the determination of university status. A founding principle of the binary system was that universities were places for the advancement of academic knowledge while colleges provided vocational education. That principle was compromised from the outset by the Australian university’s heavy involvement in professional training, and the colleges breached it by broadening their course offerings and introducing postgraduate programs, but the consequences were apparent in staff profiles. The proportion of college staff with PhD qualifications varied—it was higher in metropolitan institutes of technology than in former teachers colleges—but nowhere approached 60 per cent; they published much less, and very few had ever won a competitive research grant.51 How could they be expected to do so when they were denied research support and funded for teaching purposes only? The prospect of remedying this inequality was a powerful inducement for colleges to join the Unified National System, but they entered it at a severe disadvantage in research facilities, libraries, workloads and, above all, in institutional support. Although the institutes of technology had a research base, the majority would struggle to bridge the gap. Cross-sectoral amalgamations created a debilitating division between academics with an established track record and those from the colleges who were expected to make good their deficiency.

A corollary of the emphasis on research was a depreciation of the colleges’ teaching mission. They had offered a broad range of qualifications, certificates, associate diplomas, diplomas and degrees, to a diverse cohort of students. With their wider geographical coverage, they were more accessible; they took in a higher proportion of disadvantaged students and were more responsive to their needs. Since colleges maintained closer relations with industry and the professions, their courses also had a more practical orientation. A recent review of engineering had found that the students in several universities with strong academic reputations were ‘far from satisfied with the curriculum and teaching’, whereas the more practical ‘courses and teaching in the major institutes of technology are regarded favourably’. A subsequent review of accountancy admonished the larger established universities for not ‘matching their progress to their own particular client groups with the same level of perceived effectiveness’.52

The distinctive qualities of colleges were coming under strain by the 1980s as they sought to emulate the more academic orientation of the universities. Greater importance was attached to degrees and postgraduate awards; those who taught at this level acquired the research qualifications and aspirations of their university counterparts—for, as a consequence of the contraction of the academic labour market during the steady state, the colleges absorbed those who were unable to gain a university appointment. Now, with the formation of the Unified National System, this mission drift turned into a stampede. Colleges that were incorporated into universities were expected to drop lower-level courses and make their degree programs conform to the university mould. No longer constrained by external accreditation, the colleges that resisted amalgamation were free to develop new awards that matched their new university status.

‘The new arrangements will promote greater diversity in higher education’, the White Paper declared. A year later Dawkins reiterated that the end of the binary system would not see the demise of advanced education as ‘a practical, vocational and accessible form of higher education’. Rather, ‘the outstanding achievements of the former advanced education sector will be enhanced within a new and more flexible framework’.53 This claim was challenged from the outset. Lynn Meek, an expert on amalgamations, and Arthur O’Neill, a senior administrator at Lincoln Institute of Health Sciences who had already experienced one, warned in 1988 that ‘the direction of the proposed change’ seemed to be one-way; colleges were to be admitted to the Unified National System but, in the absence of safeguards to protect their mission, they were likely to become ‘poor cousins in the family’. A year later, as the effects of the mergers became apparent, Meek’s colleague Grant Harman condemned the destruction of college values: ‘CAEs generally are being swallowed up by mega-universities.’ The chair of the ACDP, who as principal of Roseworthy Agricultural College was about to suffer this fate, called on Dawkins to make an agreement to protect college values a condition of all such mergers.54

Many college academics felt the same. ‘The move to an integrated system of tertiary education was a wonderful opportunity that has been hijacked at our institution by ambitious, elitist, money-hungry self-seekers’, said one.55 Staff surveys conducted at this time found widespread discontent. Those who worked in colleges welcomed the prospect of equal funding within a Unified National System and increased opportunity for research; they also resented the aggregation needed to satisfy the membership requirement. Mergers within the college sector usually caused less distress than those that annexed colleges to a university, although the mood within the colleges was more despondent: 17 per cent of academics at the University of Sydney reported poor morale in a 1989 survey against 44 per cent of those at Charles Sturt and the University of Western Sydney. Reasons for unhappiness included heavy workloads, an unsupportive intellectual climate, inadequate support, a heavy teaching load and ‘too many bloody competing demands’—complaints indicative of the deteriorating work environment throughout higher education during the 1980s.56 A longitudinal study conducted in 1979, 1984 and 1990 reported a growing alienation in both universities and colleges.57

The view from the top suggested an intensification of these pressures. A separate survey of vice-chancellors, directors, principals, registrars and heads of governing bodies found an expectation of increased competition and stronger management making use of strategic planning and performance management. The college officers were far more supportive of abolishing the binary divide than their university counterparts, although university officers regarded cross-sectoral amalgamations with greater favour than the college ones did. Older universities saw advantages in reducing the number and size of institutions, newer and smaller universities did not; but both agreed that differences in teaching and research would and should persist within the Unified National System. Indeed, most respondents expected that a ‘de facto binary system’ would emerge over the next ten years whereby a few institutions were funded for a full range of teaching and research and the rest confined mainly to teaching. Among both colleges and universities there was more support for diversity—within as well as between institutions—than confidence that it would be sustained.58

The elevation of the colleges to university status did indeed result in a loss of diversity. The specialist arts and agriculture institutions lost their separate identity. The networks of teachers colleges, with their long commitment to education, were mostly broken up, leaving the former institutes of technology and regional colleges to emulate the academic orientation of the established universities. There is no agreement on the reasons for this convergence. Some see it as the work of ambitious college heads, some argue that it was caused by college staff wanting university pay, conditions and titles—in more than one cross-sectoral merger the question of whether principal lecturers would become associate professors or mere senior lecturers absorbed a disproportionate amount of attention. Another explanation is mimicry, hardly surprising since the AVCC advanced and the task force accepted such a conventional definition of a university.59

Diversity takes many forms. It can apply to different types of university and different activities within them. There can be horizontal diversity, where the differences have no implication for status or resources, and vertical diversity that establishes a hierarchy. Australia’s Unified National System enshrined a single type of university, in contrast to other countries that retained more pluralistic higher education sectors (exemplified by the United States with its multiplicity of private and public institutions, from the research university to the community college). Here there would be very little variation since all universities were funded according to the same formula, all domestic students incurred the same HECS charges and all research was judged by the same measures. By inhibiting horizontal diversity, the Unified National system promoted vertical differentiation. The older metropolitan universities, with their accumulated prestige, were able to extend recruitment of school-leavers across and beyond state boundaries while consolidating research supremacy. They would forge ahead, leaving others behind.60

The government insisted that amalgamations would stimulate greater diversity in educational programs and research endeavours; it also claimed that there would be efficiency gains from shared management services, more effective use of buildings and equipment and more flexible deployment of resources. Some transitional costs were anticipated as new facilities were provided for merged institutions and courses were rationalised, so the Commonwealth provided additional funding for capital works and used the Priority Reserve Fund to distribute $19.5 million for amalgamation expenses and $9.1 million for early retirement or redundancy schemes.61 These sums were grossly inadequate. The integration of merged entities was protracted and painful, the financial costs high. An early econometric analysis calculated that scale efficiency produced cost gains of between 3.6 and 13.1 per cent when universities merged with colleges, 3.1 per cent at most when only colleges were involved.62 But in multi-campus universities these savings were elusive. Apart from the fixed cost of local services, they required coordination that spawned additional layers of management. Above all, mergers absorbed time and energy and generated anxiety and conflict.63

There was a further, unacknowledged reason for bringing universities and colleges into a Unified National System. The Minister was intent on expanding higher education at a time when public outlays were under severe pressure. We have seen the resistance he encountered in Cabinet to his requests for a modest increase in expenditure, and there was no chance of persuading his colleagues to build new universities. If he was to achieve growth, he had to press the colleges into service; and if they were to be accorded parity, they needed adequate size and scale. Even though the ensuing process of consolidation required statutory ratification by the states, Dawkins had no intention of allowing them to control the outcome. His goal was a national system, and the Joint Planning Committees played a negligible role in determining its composition. Instead he used the EFTSU benchmarks to goad the vice-chancellors and principals into voluntary mergers that were subject to his approval.

Whether eagerly or reluctantly, the overwhelming majority complied, and in a brief, concentrated period of intense bargaining, the map of Australian higher education was redrawn. But by turning the initiative over to institutional heads, Dawkins allowed the outcome to be determined by institutional self-interest. Given the procrustean nature of the Unified National System, this laxity in arranging its composition was remarkable. Amalgamation followed no consistent logic and yielded no coherent pattern: the thirty-six universities that emerged were far from unified in coverage, capacity or coherence.

The claim might be made that the mergers have proved remarkably durable: apart from offloading unwanted campuses, every one of them has remained intact since 1993. A more telling observation is that since they were completed, student numbers have increased fourfold, but the only additional public university was formed on the Sunshine Coast in 1996. A scattering of private universities and non-university providers still has a very small proportion of enrolments. Growth has therefore proceeded along existing lines by a process of accretion. All universities conduct teaching and research; all of them are comprehensive in their coverage; all rely on the same sources of revenue. The formation of the Unified National System seems to have exhausted the country’s capacity for institutional innovation.