Went to show…at the end of the reel there’s a blackout while the projectionist changes reels. And it always happens at the critical instances in the movie.—February 15, 1945

That first Wednesday soon became a routine. Dad and I continued to eat lunch together every week for the remainder of the school year. But as summer approached and temperatures soared into the nineties, we decided that soup no longer sounded very good. Dad had heard that a local diner, Mr. Ed’s, served his all-time favorite: eggs Benedict. So we started going there for breakfast. By the time colder weather came, we had become comfortable in our new routine.

I continued to read the letters, but I saved my questions for our weekly time together. Each Wednesday, I took out a list of questions and then gently fit them between bites of eggs Benedict and crispy hash browns. Sometimes, the answers flowed easily. But more often than not, they didn’t. I walked a fine line that was now far too familiar. His responses to the questions were completely unpredictable. Questions that I thought might upset him didn’t. Questions I didn’t think would upset him did. It seemed to be less about the subject matter and more about the memory a word or thought triggered.

Between Wednesdays, I emailed questions to him; sometimes he responded, sometimes he didn’t. The whole system wasn’t very efficient and didn’t fit with my methodical personality. Still, my late night transcribing had finally added up to one notebook of letters completed and three to go. I went to bed each night with my neck aching and my vision blurry. It was a laborious task, trying to read his tiny handwriting, gleaning information from the letters and from him, and then attempting to form a mental timeline and keep up with the questions that popped into my head relentlessly. And then there was the military jargon and the 1940s language that I didn’t understand.

My husband had been right when he worried this would take a lot of time. Perhaps he knew me better than I knew myself. He knew I couldn’t simply type the letters and leave it at that. I had to understand. One letter at a time, I kept telling myself. And that’s how it went.

I sat on my bed, pillows propped behind me and comforter pulled over my legs. I switched on the heating blanket and balanced my laptop on knees. My kitty jumped on the bed, circling a few times before curling up on my feet. I opened the word processor to the letters I’d transcribed so far. I’d finished one notebook of the original letters, one hundred pages. But as I scrolled down, I realized I wasn’t really done with them. There were many places in his letters where I couldn’t decipher his writing. Instead of stopping when I came to a place like that, I’d moved on. But now, looking at it, I hated all those blank spaces on the page.

I dialed Dad’s number.

“Dad,” I said, “I need to come over tomorrow.”

“Come on over anytime,” he said.

“You might want to hear why before you agree to this,” I said.

“Well, as long as I don’t have to do any work,” he joked.

“Actually,” I teased, and then added, “it is a bit of work I need from you. But I’ll do most of it.”

I arrived the next day with my laptop and one of the notebooks.

“OK, Dad,” I said. “Let’s get started.”

“I don’t like the look of this,” he said. “This definitely looks like work.”

I handed him the notebook of his letters. He looked at me as if I’d just put a snake in his lap. But I pretended not to notice. I opened my computer and scrolled down, hoping this would work.

“Let me explain how I’ve been doing this,” I said. “Your handwriting is sometimes hard to read. So when I was typing and I came to a word or phrase I couldn’t read, I left a long line of dashes.”

I turned the laptop around and showed him.

“Now all I have to do is go back, delete the dashes, and fill in the blanks,” I said. “And that’s where you come in.”

“I don’t think I can help you there.” He laughed. “I can’t read my own handwriting, you know.”

“Well, we can at least try, right?” I asked.

“I guess,” he replied.

“OK,” I said. “Turn to the letter dated January 22, 1945.”

“Got it,” he said.

“OK. Now go to the first sentence of the last paragraph,” I said.

And so it went for the next hour. Most of the time Dad was able to fill in the unknown words easily. But sometimes it was more difficult and I’d kneel next to his chair as we read and reread the sentence, looking carefully at each letter, comparing it to others, or using the context of the sentence to figure it out.

“You know why these are so hard to read?” he asked. “I wrote whenever I could and that was usually late at night in my bunk, with very little light.”

“Hmm,” I said. “That’s not how I pictured it. I pictured you at a desk or something.”

“Actually, I rarely sat at a desk or table to write, until I started working in an office. But that was later in the war. Is there a place where my letters change from being handwritten to being typed?” he asked.

“Yes, there is. And your typing is a lot easier to read than your handwriting,” I teased.

We finished several letters that first day. And in the coming weeks, I found it was something I could fit between the rest of my life—between running errands and paying bills, or between grocery shopping and cleaning the house, an hour here and an hour there. It was a slow process. So many letters had accumulated that, when I had the time, I wanted to just barrel on through. Dad didn’t have the same sense of urgency. In fact, he usually ended our session before I was ready. He was always nice about it. In fact, he simply threw out hints: his back hurt, he had an errand to run, he wanted to take an afternoon nap. “Do you want to stop?” I’d ask. The answer was always yes.

I began to suspect there was something more to the often abrupt end to our time together. But regardless of the reason, when he was done, we were done.

Feb 15, 1945

Dear Folks,

Believe I wrote you once today but I have half an hour to kill before show time. Jonesy just checked with the doctor a few minutes ago and the doc took him right up to the local hospital for a few days observation. All of a sudden, just like that. It’s just a few blocks from here on the same base so I’m going to take his mail to him and visit him now and then. He probably won’t be there long.

I really stumbled on to something today. Probably of no importance now but you never can tell. Had mail-man check my mail-card at the main post office while he was over there yesterday. He says according to that, I was assigned to the office on another base as a communication specialist. Even showed what room I worked in and everything. He said he didn’t change it because he thought I lived here and was working over there. Evidently when I was up for transfer a couple of weeks ago I was assigned to this other base. It’s just the main office of this base I’m working at now. Over all of the other small bases around here—much closer to town and much nicer surroundings. They have every fourth day off and are usually there for a year or two years or even longer. A good deal. Don’t have any idea what it will mean as far as getting a transfer when and if I leave my present location. Maybe that it’s just held open for me when I get ready to go. Sure hope so. I wouldn’t mind the place as long as I have to be in anyway.

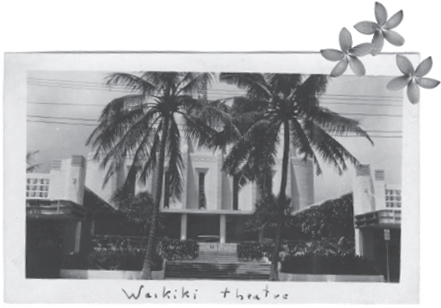

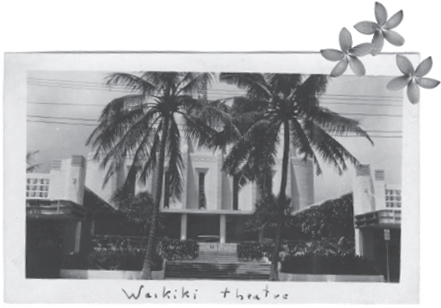

Didn’t do anything, as usual, today. Took a shower and shaved. I went to show and slept. The show, “To Have and Have Not” was very good. Most of the ones we see are a little old, but all of the best grade. We have two theatres—one is indoor and in one of the buildings that houses the communications school. All the buildings (with few exceptions) of any semi-permanent nature are of the Quonset hut type. You’ve probably seen ’em in shows. They are made of the corrugated tin in a big half-moon shape with inside made to fit the job they are to perform. Hospital, chapel, schools, living quarters and so forth. As I started to say about shows—this one here has just one projector. So at the end of the reel there’s a blackout while the projectionist changes reels. And it always happens at the critical instances in the movie. Then at the other theatre which just opened—there’s a show every night. It’s in a huge fan shaped area with a big closed in stage and screen. Has just hardwood barracks with no benches with no backs for seats. That’s all the officers have too, so we don’t holler.

Very interesting, all this, huh, Mom? Say, if you should ever want to send anything this way—candy, cookies or anything at all put them in a good wood box or metal. Cardboard boxes aren’t worth sending—they are wrecks when they get here.

Write. Love, Murray

A month and a half into his time on Oahu my father decided to find out why he wasn’t getting his mail regularly. Everyone else seemed to. But Dad went days without a single letter and then got a bunch of them. So one day, he decided to hop in a jeep and go over to the post office. When an officer told him the address he had for my father, he was dumbfounded. The address was wrong.

Then the officer took him to the address. Inside the communications building was an office. My father’s name was on the door. A desk was in there, with supplies and papers spread about as if he worked there every day. He didn’t know just why, but it sent shivers down his spine. No one could explain it and my father didn’t pursue it any further. As far as he knew, the office remained just as he’d seen it for the remainder of the war.

But years later he would reflect, “It was eerie. I didn’t know what it meant. Maybe it was just a mistake. Maybe it wasn’t.”