April 25, 2129. On Virgo, upbound Earth to Mars. 149 million kilometers from the sun, 166 million kilometers from Mars, 3.8 million kilometers from Earth.

WE OPEN THE hatch into Farm Section 1 with a utility stick, not knowing much about what might have gone where. Nothing comes at us, so we pull ourselves down the ladder past the big piped-light ports to the first growing deck, almost 15 meters down. Instead of vertical coretube-to-hull walls, like the pressurized cargo section has, farm sections are divided into growing decks, with long narrow beds you walk between to do whatever it is you do with plants. (All I know about them is roots down, leaves up.) After the first big drop the growing decks are only about 4 meters apart; climbing down an enclosed ladder through several levels feels ultra confining.

The piped sunlight ports in the ceilings make every deck warm and bright. It’s humid; wet soil and water have spilled from bins that didn’t close fast enough, or jammed open. Looking toward the nose, I see mud, where soil beds and water tanks have dumped against the bulkheads.

There’s a bigger mess on the bulkhead at the next level. I point it out to Glisters.

“Yeah, and that’s not good. Mud flows, and when we fire the engine for the course correction, ugh. The tail end mud pile will just flatten out on the bulkhead without changing the center of mass much—but all that mud up near the nose will drop 850 meters at a tenth of a g or so.”

“Now that you put it that way, I don’t like it either,” I say. “Emerald, have you been getting this?”

“Yeah. So the ship will boost at about a tenth of a g, and while that’s going on, the gravity inside will be a tenth of a g, right? So falling 850 meters at a tenth of a g means… uh—”

“That mud will hit the tail-end bulkhead as hard as if it fell from 85 meters on Earth—like from the roof of a twenty-storey building. Of course some of it will hit stuff on the way down, but that’s not necessarily good either.”

Emerald shakes her head. “But that mud is only maybe 10 centimeters deep—not much more than up to our ankles; sure, it’ll be going fast, but—”

That doesn’t sound right to me. “But there’s a lot of bulkhead—and mud is heavy. What’s the total mass going to be like, that falls from there and hits the tail-end bulkhead?”

Glisters stops and punches his wristcomp. “Okay, 10 cm deep by… hmm, that’s still 18 decks worth of it… okay, about 650 tonnes. If the density this thing is giving me for ‘loose soft mud’ is accurate. They don’t define either loose or soft but that stuff is definitely mud.”

“We can agree on that,” Emerald says. Everyone has been gathering around us while we sorted it out. “Definitely mud. All mud, that mud. So 650 tonnes of it is going to come pile-driving down like it fell from a good-sized office building. I guess we have to get it someplace under control, then, before we can course correct.”

Wychee says, “Em—I mean, Commander—”

“Wychee, we’re on break. You have best buddy privileges—”

“Well, whatever. I have an idea. You don’t need to put all the mud back in the right bins. You just need to keep it from moving around, right? So I was thinking, in normal operation—they must have to rearrange beds and move soil? Which means they must have power equipment for moving mud around and storage spaces to put it into. So shouldn’t we look—”

Glisters is nodding. “Yeah. Yeah, you’re right. All we really have to do is get the nose-end mud pile under control, and for sure they have gear to do it with. Thanks for thinking of that; I was drowning in the complications and you saw the real issue.”

“What issue?” Fleeta asks, obviously having some trouble following this.

“Either the squashed-like-a-bug issue,” I say, “or the giant-hole-knocked-in-the-tail issue.”

She’s scared but enthusiastically joyful, like she’s about to go on a really great roller coaster. “Are we gonna—”

“No, because Wychee’s idea has taken care of it,” I tell her.

She smiles the way a little kid will when something was scary but Mom says it’s okay, and unselfconsciously takes my hand. I look into her eyes, and think about what she’d have thought of this adventure when we were ten or eleven, and how much we’d have wanted to be here together. Her expression is blankly ecstatic; she thinks nothing but she feels great. I’m afraid of crying, and I look away, but I don’t let go of her hand.

There are no windows in the hull-level deck except in the Forest—the light is all piped to come down at the plants from above. It seems like a room with a warm skylight.

As we move farther noseward, we are careful to come to a full stop and take a grip every 3 or 4 meters. Gravity shifts from hullward to noseward very quickly, and we don’t want anyone to abruptly fly away and slug into one of those tree trunks.

Though most of it must have been trapped when the beds slammed shut, mud still oozes down the walkways, headed for the nose. Now and then a blob breaks off and flies on ahead of us, past the closed beds, spattering on the tree trunks down in the Forest.

“You know,” I say, “I bet the Forest isn’t as pretty as it was. Maybe we should give this up.”

“Let’s at least look,” Emerald says.

By the time we’re there, we’re climbing, albeit easily, down the hull wall, and the mud drops on us in a constant drizzle that hits with enough force to sting an upturned face. The grass between the trees is all smeared with mud and water slowly dribbling toward the nose, and the lower trunks are a muddy mess. All but the least ripe fruit has shaken loose and plunged into the mud below.

It’s nothing like it was when I was here with Destiny. And Destiny—

I’m crying. Hard. Really hard, as in, I sit down on a muddy trunk and just sob. Fleeta hangs on to me and keeps saying she’s so sorry, she’s so sorry, even though I can feel that she’s stifling giggles. Then everyone’s crying, and the place sounds like a big echoey funeral. The light from the windows flashes off and on, turning the green twilight white and highlighting the tear streaks in the dirty faces and the filthy misery of our clothes.

Fleeta does not cry, because she can’t. Maybe that’s why Derlock doesn’t cry either; he sits staring, waiting for one of us to do something that matters to him.

After a while, Emerald says, “I guess that needed to come out.”

Stack says, “I’m surprised we weren’t all like that right after it happened.”

Emerald shakes her head. “I’m just being reminded about something my mother said, and she’s right. Meeds always show people running and screaming and freaking out when something big happens, everybody always acts like panic is the most common thing that happens, but you know… if you look at natural disasters, big accidents, terrorist attacks, any of that… mostly people get real calm and do what needs to be done. Everybody who ever planned to turn bombs loose on civilians was planning to start a panic, but that’s exactly what doesn’t happen. When my mom—Do you guys all know?”

It takes me a moment to realize that she means, do you all know how my mother became a celeb-eenie? and our real answer is yes, but you’re so embarrassed about it we never bring it up. By then, slightly too quickly, Glisters has said, “Why don’t you tell us, Emerald? I don’t think all of us know, or know the whole story.”

The gist of it is that her mother used to be a plain old talent-eenie, really about the plainest kind you can be—she was this really ultra-talented kindergarten teacher, like everybody wants their kids to have, one that every kid wishes was his or her real mommy. Then one of the nihilist-terrorist groups, the kind that want to ruin Perma-PaxPerity because they think people need to be scared and in pain, seized the school. Emerald’s mom talked them into letting all the kids go, and just keeping her as a hostage. And then got them to all sit down to tell her what the matter was, putting them all on one side of the room, and abruptly dived under a desk. She’d guessed right, that the rescue team was already in place by then; they knocked down the door and killed all the terrorists within a couple of seconds.

“See, what Mom said was, if you’d asked her what she’d do in advance, she’d have predicted she’d panic. She thought that because she’d always been told that it was what people do, and besides she was scared of weapons and hated the idea of violence and thought that if she saw any of her kids scared and crying and couldn’t do something about it, it would just destroy her. Well, she just went all calm, took a deep breath, and was there. And much later on she made me read about what really happens in sudden crises. And you know, all the big accounts about whole cities panicking and people running around aimlessly screaming and all that? Mostly written by people who weren’t there. Sometimes criminals take over and do awful things, but even they do the awful things in a pretty calm, organized way. There’s more than two centuries of evidence; at least at first, right when things are going bad, people rise to the occasion.”

Marioschke, looking down from the muddy branch where she’s sitting, starts to cry harder. “I could have,” she says. “I knew I could stop, and go find you all—”

Fleeta flees from me, clambers awkwardly out to her, and holds her.

I say, “I don’t think any of us has to apologize about anything right now,” not because I mean it—I’m actually pleased as all sheeyeffinit that Marioschke apologized. But now that she has, I want her to be a functioning member of the team, and it won’t help for her to feel perpetually guilty.

Emerald nods, catching my eye, agreeing with me, and softly adds, “Anyway, we’re a better-evolved species than our meeds give us credit for. We’re usually okay during the worst; afterward we fall apart. Like we’re doing now.” She looks around, sniffling. “This place was so pretty yesterday.”

The silence seems to stretch on forever until F.B. says, “If it’s not true, why do we make so many meeds with people screaming and panicking and all?”

Glisters makes a strange little noise. “Visually more interesting. Ever notice that in all the panic scenes, there’s a hot girl right where your eye goes?”

Stack snorts. “The panic act makes them scream and get intense expressions. And running makes skirts fly up and boobs bounce around.”

There is a chorus of female raspberries. Abruptly, Glisters stands and walks along a tree trunk to the turf-covered hull. “Ha, they’ve built in a net that holds the sod in place. I guess they’d have to for thrusting. Okay, one avalanche hazard we don’t have to worry about.”

“Hey,” Wychee says, from where she’s been exploring up toward the coretube, “the trunks up here don’t have much mud. And they’re still big enough to stretch out on.”

We follow her up there; she’s right. We’re still dirty, but it feels good to stretch out on a clean surface, without mud spatting down on us, and near the coretube, the damage to the Forest is not so apparent.

After a while, Glisters says. “Hey, Wychee, you’re not just right, you’re brilliant. I just did a search. All the farm sections are equipped with a suction system that we can configure to put all the mud into storage tanks. And every bulkhead and deck has suction drain inlets, and the ship has twenty robobarrows that can be told to just follow you around, take the dirt as you load it in, and go feed it into the nearest suction inlet. We’ll all have to shovel but we won’t have to haul.”

“Attention, Engineer,” Emerald says. “This is your commander speaking. Rest your damned brain, so it will be ready for me to exploit again.”

“Yes, ma’am. I was resting it by working on Wychee’s idea instead of on my own.”

“All right, then, both of you stop thinking. This is some kind of conspiracy.”

Everyone’s quiet; I like the way the trunk feels against my back. I wish I could nap, or maybe cry some more.

“The sun feels good on my feet,” Fleeta says. “Do you suppose it’s okay to take my slippers off?”

Derlock makes a rude noise. “What, you think the Slipper Police might be hiding in the trees?”

“She probably can’t remember whether there’s anything dangerous,” Emerald says in the quiet way that I am coming to realize means you are ultra dead. “Fleeta, you can take them off, but make sure you don’t drop them, because they’ll fall all the way down to the mud in the nose right now.”

“Okay.”

I notice that the warm flashes of sun do feel good on feet, and take my slippers off, too; I’m glad the crew bunk room has a shower and a Phreshor, because I’m going to need both pretty seriously when this long day is over.

“Well, I’m too bored to sleep,” Derlock says. “Why don’t all you super-genius goody-boys and goody-girls amuse me and talk about your fucked-up childhoods.”

“Actually, I had a great childhood.” Glisters stretches. He’s on the trunk next to mine. For the first time since the accident I notice how small and short and pink he is, and what an enormous head he has relative to his body. I used to notice that every minute or so when I was around him, but I guess when a guy becomes your main hope of survival, it’s not so important that he looks like something that would crawl out of a swamp in a fantasy meed (especially now that he’s splattered with mud). “I liked being a kid. I did a lot of fun stuff.”

“So you played with your little computer and your little lab and went on little nature hikes—” Derlock begins.

Crazy Science Girl inside me wakes up Psycho Ex-Girlfriend and they summon Pilot Susan. It’s like a whole convention of us Derlock-haters in here. “And all those little skills and all that little knowledge that Glisters picked up might keep us alive all the way to Mars,” I say. “Call me a sentimental chickie, but I don’t consider staying alive to be little, at all.” There’s an awkward silence.

I re-break the ice that I just froze onto the conversation. “I had a zoomed childhood, too, I went a lot of places to see n-nillion things just ’cause I liked them.”

“I remember,” Fleeta says, beaming at me. Maybe I will cry some more.

Derlock grunts in exasperation. “I didn’t want to hear about your childhoods. I was being sarcastic.”

“We didn’t feel like hearing your sarcasm, so we talked about our childhoods,” I say.

Emerald is sitting up on one elbow; she raises an eyebrow, I shrug, and she says, “Derlock, if you have any ideas that are actually to our benefit—”

“Will you at least have the grace to admit my plan is paying off a lot bigger than anyone could have imagined? When we land on Mars we’ll be celebs like nobody else! Our recognition numbers will break all records!”

A long silence. No one quite knows what to say. Back in Baker Lounge, he’d have hypnotized us with that; here and now, it’s like trying to remember a foreign language you were never very good at.

“Can you play chess in your head?” Glisters asks me.

“No, and for the first time in my life I wish I could.”

Wychee says, “D three.”

Glisters replies with “E five.”

“B D three.”

“N F three.”

In minutes, trying to follow their game sends me into deep slumber.

April 26, 2129. On Virgo, upbound Earth to Mars. 149 million kilometers from the sun, 165 million kilometers from Mars, 3.9 million kilometers from Earth.

Emerald decides that, since there are only a few huge containers in the vacuum holds, and Glisters says they don’t need to be moved, just tied down, most hands will be more valuable on shovels. She says, “Glisters located pressure suit storage. Why don’t you take Stack and Derlock up to the vacuum holds and dog the loose stuff down?” Our officer telepathy is getting pretty sharp; I hear that as: Take these two whiny boys off my hands and make them do something useful.

Vacuum Cargo Section 1 has cargo walls with a handling deck, and Vacuum Cargo Section 2 has decks and freight elevators. Each of them looks like a warehouse impersonating a submarine. The cargo in them is stored in boxes, cylinders, pyramids, and spheres, some as small as PersKabs, some the size of two-bedroom houses. For the moment walls work like decks and decks work like walls; we have to keep reminding each other of where down will be when it’s all stabilized.

In soundless vacuum, we hear only the scrape of our own boots, and our pressure suit radios. Stack is uncharacteristically doing way more than his share of the work; Derlock predictably does much less. We only have to spin three crates around to match hooks with the floor. It goes fast.

When Glisters confirms it’s all locked down in both vacuum cargo sections, we airlock out, strip out of the pressure suits, and go to share in the shoveling.

Derlock bounds on ahead and pops through a door, leaving Stack and me to climb down the coretube together. The moment we’re alone, Stack says, “I know you won’t completely trust me, but I’m with you guys. 100%. Derlock is crazy.”

“You sound worried.”

“Worried? Sheeyeffinit. I’m scared. I always knew he was evil, but I’m starting to think he’s been crazy for a long time.” Stack’s face is usually flat and expressionless with an overlay of contempt, his attempt at styling Knowing Cynic, or maybe old-style Snotty Arrogant Punk, but this isn’t his usual suppressed sneer; he looks really afraid. “Derlock was not in the lounge where the Virgo crew caged most of us,” he says quietly. “Glisters, Emerald, and Fleeta went off to finish the tour, after Derlock steered the rest of us into being all rude and I-don’t-care and like that, so we were all bottled up watching meeds and eating snacks. Then Derlock talked to the guy watching us, real quiet, and bzzzp, Derlock was gone for three hours.” Stack works his way crosswise on the handholds toward the doors to the active farm section. “I’m sure he knew something was going to go wrong for Bari and King. I even think maybe he knew that something was going to go wrong for Virgo. Last night, before the accident, he talked privately to me about which girl I wanted to have, like he could just give one of you to me. Stuff like that.”

“He thought he could do that?”

“It’s so hard to know!” Frustration is choking him. “After being his bud for so long, I don’t know how much is real and how much is Derlock’s craziness. Sometimes he imagines having all this power, like it is just going to come to him. Mostly it’s internal botflog, stuff he tells himself so often he believes it, he just expects things to work the way he wants them to. But the weird thing is sometimes they do. Maybe he was just ready for the accident to happen because he expects to have everything he wants all the time, or maybe he knew the accident was going to happen.”

“You are suggesting,” I point out, “that Derlock murdered a hundred and forty people.”

“I’m saying I can’t convince myself that he didn’t. Maybe it’s just that crazy way he just imagines things will work, because he wants them to, and then, if they do, he thinks he made them happen.”

“You think it’s just delusions?”

Stack stops climbing for a moment, hanging lightly by the handholds. “I’m not Derlock. If I was evil and planning to cause that accident and then take over, I’d study the ship till I could do ten times what Glisters is doing. But it’s him, and not me, and the way he thinks, probably he knew there was a cockpit in the pod, and he just expected that whatever he did when he took it over would work. He really believes that once he wants a thing to happen, it happens. And, you know, well, the way things are now, with all of us caught here with him… that’s all I wanted to tell you.”

Embarrassed, or maybe afraid, Stack jumps down the coretube in big bounces, grabbing handholds like a crazed monkey. I climb after.

By the time we join shovel duty, they’ve finished with the mess on the Forest bulkhead and done about a quarter of the rest. Stack and I share a robobarrow; Derlock has partnered with Emerald, and I can hear his voice, constant, low, sounding reasonable, sounding affectionate, sounding sexy, sounding whatever he thinks will work. I remember it, of course—it’s only been a couple of days—and I’m glad I’m too far away to hear what he’s saying. I just hope she’s far enough away, physically or mentally, not to listen.

When I come back to the cockpit after a fast run-over with my cleanstick, Derlock is sitting next to, and slathering the charm and admiration on, Glisters, who is reveling in having tech stuff to explain and a willing audience. “—the antenna is in the external storage bin just outside this tail-end airlock, not far from where we have to mount it. As soon as one of us is all the way up to speed in an evasuit, and has rehearsed the moves enough, we should be able to put the antenna up and yell for help. But we only get one shot with this antenna, and we can’t afford to lose it, so whoever is doing it—”

“Dibs on that,” Stack says. “I’ll go. When do I start practice?”

“How about after I’ve had some sleep and some time to think through it all?” Glisters says. “So I don’t overlook something or have you learn something wrong? A day or two won’t matter at all, and like I said, we’ve got to get this right.”

“Why does Stack get to do it?” Derlock says, like it’s a trip to the ice cream store.

“He’s strong, he volunteered first, and we know he can do it,” I say, “Glisters, what’s so precious about this antenna? I thought an antenna was just a long wire.”

“You’re about a hundred years out-of-date. This isn’t even really an antenna; it’s a submillimeter-wave detector array.”

“Do we have to waste time fussing about how we say it?” Derlock is fishing for a way for me to quarrel with Glisters.

Glisters and I exchange one glance and just bomb Derlock flat with tech talk for the next half hour.

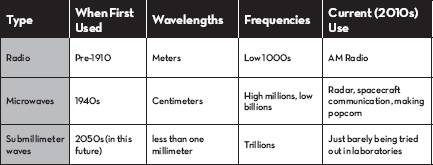

Notes for the Interested, #13

Over time, waves get shorter, and frequencies get higher

Every form of communication that will work in space is some form of what physicists call electromagnetic radiation: radio, microwaves, light, X-rays, and other things. The wavelength is the distance between peaks of the electromagnetic waves that it is made of; the frequency is the number of waves that pass by in a second.

Small wavelengths mean big frequencies and vice versa. In 1906, Einstein figured out that in the vacuum of space, all electromagnetic radiation moves at one speed, c, the “speed of light” you’ve heard about. For any electromagnetic radiation, then, the wavelength times the frequency will be equal to c. (To see why this is so, think of it this way: the electromagnetic waves are like a train passing by. The wavelength is the length of the cars, and the frequency is the number of cars that go by in a given time. If all the trains move at the same speed, just as all electromagnetic waves do, then if a lot of cars go by, it’s because they’re all short; if the cars are long, fewer cars will go by in the same time.)

Ever since the first radios, people have been using shorter and shorter wavelengths (which means higher and higher frequencies):

Why do engineers keep moving toward short wavelengths/high frequencies? Because of two things they explain in more detail in college physics:

In the 2060s of this future, as humans began to venture away from the Earth/moon system, higher frequencies and shorter wavelengths meant you could communicate with spaceships via a tight beam that could be more easily picked out from background noise.

This also meant a different kind of “antenna”—the word is in quote marks because it’s not really an antenna at all as we use the term today. Technically an antenna is a conductor that resonates with some frequency of electronic radiation; when it resonates, an electric current forms in the antenna that we can detect and process into a signal.

Any big piece of metal will resonate with radio waves. But submillimeter waves need submillimeter antennae—tiny dots of semiconductor that resonate with their very short waves. Furthermore, to answer a tight-beam signal, it’s necessary to know the exact direction it came from (the whole point is not to broadcast to the whole universe, as you did with radio).

So what you really need is two of those detector dots: When a signal shows up strongly in both dots, the line between them is pointing at the source. If you put one dot on the center of the glass covering of a dimple, and scatter dots all over the inside surface of the dimple, then when the center dot detects a submillimeter wave, one other dot will also detect it, and a computer can immediately calculate the direction from which dot on the dimple fired. In fact it can immediately return a signal and establish two-way communication just by going through those two dots.

CROSS SECTION OF A SUBMILLIMETER WAVE DETECTOR DIMPLE

Actually, it’s only half a centimeter across. Detector spots form a web half a millimeter apart all over the inside; there are 628 detectors on the surface of the dimple, and one in the center. Signal from Source 1 comes into Detector Spot A, but since it didn’t also come through the center detector spot, the software ignores it, just like it does the signal from Source 2 coming into Detector Spot B. But signal from Source 3 (black dashed arrow)—which might be a spaceship, a space station, or a transmitter in orbit around one of the planets or the moon—comes in through the center spot and Detector Spot A, so the software reports the signal and its direction. To reply to it, a transmitter spot (not shown) next to Detector Spot A sends a signal back toward the center (smaller gray arrow), and the transmitter spot at the center reinforces it by sending the same signal exactly in phase, producing a very strong directional signal (large gray arrow) that goes straight back toward Source 3.

Thus in this future, “antenna” is just the name still used for “the thing the signal goes out through,” in much the same way that the front instrument panel on a car is still called the “dashboard,” even though it no longer has the function of keeping mud from spraying up from the horses’ hooves. The antenna is now a detector array—a surface covered with detector dimples.

It’s not something Glisters or Susan could just knock together out of a spool of wire.

“—can’t knock one together out of a spool of wire,” Glisters finishes explaining to Derlock, his enthusiasm undiminished. I think about suggesting that Glisters should make sure he’s thorough about this, and show Derlock how to derive the frequency-energy relationship from the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, but Derlock glazed over a long time ago. Of course we could have had the same effect by telling him that just trailing a long wire off the tail would anger the antenna gods.

Glisters rides on. “Physically the antenna looks like a 4-meter-long post about 25 centimeters in diameter. But its surface is glass, and under the glass it’s mottled with little half-centimeter dimples, and each dimple is lined with an array of receptor spots, connected to its own processor.”

It’s fun to watch Derlock sit there in shock from the volume of explanation, and I really am interested in what Glisters is saying, but there are other things to get on with, so I say, “All right, I understand now. All those dimples and all those little computers working together are needed to keep a signal focused on one station in a tight beam?”

“That’s it,” Glisters says. “The antenna can talk back and forth in tight beams to up to 10,000 different stations, or send one really loud-and-bright signal to just one station, but there are no general broadcast stations anymore, there haven’t been since before PermaPaxPerity. We have to find stations we can link to in tight beam, ring their bells, and be invited in. The antenna was built to do that—and it would take a lot of study, time, and effort for us to build anything that could do it one-tenth as well.”

“And everything is tightbeam submillimeter nowadays?”

“I don’t think anything still uses the old longwave radio. Some things still use microwaves, like radar, toys—”

“And ovens,” Derlock says, sneering. “Microwave ovens.”

“Ovens don’t listen,” I say. “They just transmit in their own little space, like some people we know. So Glisters, that antenna can’t be replaced, right?”

“If I had to build one, I’d try. No promises, but I think I’d be able to learn fast enough to get one built inside a year.”

“So if we lose the antenna we have, or break it, we’re ultra screwed, and there will be no rescue. This has to go right the first time.”

He nods. “Exactly.”

I look at Stack. “Still want to be the guy?”

Stack smiles—not like anything is fun, but like he likes being where he is, right now. “Oh, yeah, that job is all mine.”