If I place myself in 1900, and then look forward thirty-six years, and backward for as many, I feel doubtful whether the changes made in the earlier time were not greater than anything I have seen since. I am speaking of changes in men’s minds, and I cannot in my own time [1936] observe anything of greater consequence than the dethronement of ancient faith by natural science and historical criticism, and the transition from oligarchic to democratic representation.

—G. M. YOUNG, Portrait of an Age

AFTER OBSERVING THE pilgrims thronging Lourdes in 1891. Émile Zola noted that the time and setting were right for a novel about the intractability of mankind’s dependence upon the miraculous. “Study and dramatize the endless duel between science and the longing for supernatural intervention,” he instructed himself. The theme pervades his great fictional cycle, Les Rougon-Macquart, in which modernity is dogged by the pious and the primitive. Rural folk who aspire to a higher level of awareness are weighed down by the archaic baggage they carry with them; bourgeois women surrender to a priest’s erotico-mystical predation. Everywhere, the Church casts a long shadow.

“Science” and “supernatural intervention” were indeed the competing prescriptions for France’s recovery after the Franco-Prussian debacle of 1870-71, which toppled Napoléon III from his imperial throne. These alternatives informed her social, political, and cultural life in the last third of the century, framing a bitter debate over the country’s heart and soul. It’s as if a nation divided needed only humiliation at the hands of a foreigner to turn upon itself and wage without restraint the civil war that had long excited its most implacable hatred.

For everyone, 1789 was the inevitable reference point.

There were those on the one hand who held that France would betray the best of herself if she did not remain loyal to the eighteenth-century thinkers who had fathered the Republic. On the other hand, “intransigeants” committed to the ideal of a Catholic monarchy anathematized the Enlightenment. In their view, divine grace was needed, and France could receive it only as a penitent mindful of the sins she had accumulated over the course of eighty years.

HOW THIS IMPASSE was reached is worth examining. The battle line was first boldly drawn during the Revolution—when clergy who would not pledge allegiance to the republican constitution risked exile or death, when saints’ days were expunged from the calendar and Church property amounting to a fifth of France was seized by the State to be auctioned off. Men contemptuous of the Scriptures staged a service honoring Reason at Notre-Dame cathedral. By 1801 Napoléon Bonaparte had gained power as First Consul. Mistrustful of anything clandestine, he negotiated with Pope Pius VII a treaty, or Concordat, that granted permission to worship “openly” and “freely” while reserving for himself the right to map dioceses and appoint prelates: Gallican bishops. The Church was visible, but only as an emaciated shadow of itself, with far fewer parishes than before 1789, and no priests to serve many of them. Young men who at one time might have taken vows were instead fighting and dying all over Europe. Clerical black enjoyed little prestige in a military state that treated the curate as a minor agent of social order.

The downfall of Napoléon at Waterloo in 1815 was thus an occasion for celebratory masses. Repatriated nobles and clerics went about setting things right. In 1797, Louis XVI’s brother, the exiled Comte de Provence, had instructed exiled French bishops never to forswear the marriage of throne and altar. “How indispensable it is that they support each other! May ecclesiastics imbue my subjects with this truth. … The marvelous order that is the Catholic Church will not long survive unless it remain bound to the Monarchy.” Eighteen years later, as King Louis XVIII, he restored the Church to its eminence, replacing Napoleonic functionaries with an episcopate of high-ranking aristocrats. Catholicism became once again the state religion. Religious orders reestablished themselves. Writing disrespectfully about the Church or insulting a priest constituted grounds for imprisonment; destroying liturgical objects was punishable as a capital crime; dolor and ecclesiastical pomp informed civil life; and a secret society called Knights of the Faith (“Chevaliers de la Foi”) controlled patronage. To those émigrés in whom loss had fostered humility, what often mattered most was the consolation they found in religion for their immense reversals of fortune. Not unlike the thousands who flocked to pilgrimage sites after the Franco-Prussian War half a century later, they prayed with fervor. But the war-torn nation, throughout which new church spires rose, also bred the kind of priest Julien Sorel encounters at his seminary in Stendhal’s Le Rouge et Le Noir and Emma finds at Yonville in Flaubert’s Madame Bovary— country boys unable to do much more than administer the sacraments. “All told, the clergy has never been as ignorant as it is today, yet never has true science been so necessary,” wrote Father Félicité de Lamennais, France’s great Catholic philosopher.

The Revolution of 1830, which enthroned Louis-Philippe, the Duc d’Orléans—a constitutional monarch descended from the cadet branch of the House of Bourbon, on whom Bourbon loyalists heaped obloquy—exposed the rift between Frenchmen greeting the new century and those fending it off. Knights of the Faith had subscribed to the orthodox precept that society must be a hierarchical edifice in which authority descends from God to sovereign to paterfamilias. But most of the bourgeois notables entitled to vote and run for office—those constituting le pays légal under Louis-Philippe—set up as Voltaireans.* Piety was unfashionable, if not subversive. And where piety was unfashionable, militant Catholics made themselves scarce.

Militants there were all the same, most prominently those who had associated themselves with a liberal movement founded by Lamennais in 1830 and known by the name of its journal, L’Avenir. United in the belief that religion was doomed to irrelevance so long as the government subsidized religious institutions, they called for the separation of Church and State. A disaffected populace—the same that had recently pillaged, among other ecclesiastical mansions of note, the archbishop’s palace outside Notre-Dame cathedral—would find spiritual meaning in an independent Church. By the same token, a Church no longer hostage to the powers that be would find strength in the converted masses. After forty years of republics and despotisms and monarchies eliminating one another in blind succession, what was left intact? “Only two things,” Lamennais declared in the first issue of L’Avenir. “God and liberty. Unite them and all the intimate and permanent needs of human nature are met. Calm prevails only where it can do so on earth, in the domain of human intelligence. They are no sooner separated than turmoil resumes and intensifies.” The providential laws that govern the “moral world” shone forth never more brilliantly, he declared, than during periods of transition, when “everything is being reborn, when everything is changing, when everything is transforming, when breezes of the future waft home scents of a new earth.” Having just launched a regime conspicuously disinclined to make preservation of the faith its first order of business, France might be ready at last to let religion walk free. Was a free Catholic Church not thriving across the ocean, in America? Reports to that effect would be confirmed by Alexis de Tocqueville, traveling abroad.

L’Avenir made its mark. Several thousand younger priests, many of whom served poor urban parishes, joined the movement. Threatened from below, French bishops condemned it. Lamennais and two close collaborators—Father Lacordaire and Charles de Montalembert—then set out for Rome to win the pope’s support. What they elicited instead was an Apostolic Letter that sealed the fate of L’Avenir. Loath to alienate the Gallican episcopate, to risk a quarrel that might imperil the Concordat, and to encourage liberals abroad while calling upon Austria to help him repress red-shirted republicans at home, a beleaguered Gregory XVI stood behind the bishops. “[We cannot] predict happier times for religion and government, from the plans of those who desire vehemently to separate the Church from the State, and to break the mutual concord between temporal authority and the priesthood. It is certain that that concord which always was favorable and beneficial for the sacred and the civil order is feared by the shameless lovers of liberty,” he declared in the encyclical Mirart vos. L’Avenir ceased publication. Lamennais kept faith with himself by abandoning the priesthood and writing a testament, Paroles d’un croyant (“Words of a Believer”), that earned him special condemnation in yet another encyclical. It became one of the great best sellers of its day.

Equally obstinate was Montalembert, the half-Scottish son of an émigré count, whose rhetorical brilliance matched his missionary zeal. Unable to influence policy from outside parliament, he resolved after 1837 to work from within it, as a member of the Chamber of Peers. Declaring that “those who profess or defend the Catholic faith must expect marked unpopularity,” he ruffled not only anticlerical colleagues but prelates resentful of a layman bold enough to fight for religious advantage with secular weapons in hostile territory. One of those weapons was the word on every progressive’s lips during the Louis-Philippian era—“liberté.” Liberal-minded Frenchmen were rallying behind Poles tyrannized by the czar, Italians living under a feudal regime in papal territories, German states ruled by a Lutheran Prussian squirearchy. Why then should Montalembert’s own country not afford its citizens freedom of conscience, freedom of the press, freedom of association? Above all, why should France compel parents to have their children earn baccalaureates in state institutions? Relentlessly, year after year, he championed “la liberté de l’enseignement”—meaning by “freedom” the full accreditation of schools run by religious orders. “La liberté de culte” (freedom of worship) was its corollary. In the Committee for the Defense of Religious Freedom, Montalembert fashioned a modern-day instrument of political action, supporting candidates who vowed to defend the faith. It proved itself in elections held midway through 1846, a year and a half before the revolution that would bring down Louis-Philippe.

By then, Catholic interests had gained some ground in the court of public opinion. Responsible for this shift were the dynamism of several Catholic luminaries, the social consciousness of clergy loyal to Lamennais, the pastoral work of provincial missions, and a wedge of daylight in bourgeois perception between the Church and the Bourbon monarchy. “For us French, who are slaves of words, a great thing has taken place,” Frédéric Ozanam observed in 1838, “the separation of two big words that seemed perfectly inseparable hitherto: throne and altar.”* But of paramount importance for unorthodox Catholics was the enthronement in 1846 of a new pope, Giovanni Mastai-Ferretti, who took the name Pius IX. Succeeding the archconservative Gregory XVI, Pius comported himself, until 1848, as the liberal he was thought to be by the bare majority of cardinals who had elected him. He began with a reform of civic life in the Papal States. Political criminals were amnestied, and residents were granted such unheard-of privileges as freedom of the press. Pius’s behavior astonished Europe. Count Metternich, Europe’s staunchest advocate of monarchical absolutism, fumed over it. Among progressives, clerical and secular alike, there was jubilation. France’s Protestant prime minister, François Guizot, predicted that the Church would now reconcile with modern society. In its annual address to the king, parliament praised Pius for inaugurating “an era of civilization and freedom.” Frédéric Ozanam, a well-known Catholic intellectual associated with the ideal of Christian democracy, wrote that Heaven had put on Saint Peter’s throne “a saint the likes of whom we have perhaps not seen since the pontificate of Pius V”—in the sixteenth century. The pope’s firmest supporter, he declared, was the common man.

Economic depression accounted for some of the common man’s support. Half-starved workers who rose up against Louis-Philippe on February 24, 1848, were indeed more disposed than a later generation of Parisian insurrectionists to befriend the Church, even if many of the countless immigrants from the countryside could not have identified the parish to which they nominally belonged. On February 29, the provisional government asked all clergy to bless “the people’s achievement” by chanting Domine, salvam fac rempublicam after Sunday mass. And “God save the Republic” was taken seriously. “The principles whose triumph will introduce a completely new era are principles the Church has always proclaimed, and has just proclaimed again, to the entire world, through the mouth of its august leader, the immortal Pius IX,” Cardinal du Pont, archbishop of Bourges, told his congregation.* Prelates hastened to affirm that liberty, equality, and fraternity were Christian truths (although not truly Christian, Lacordaire reminded his audience at Notre-Dame cathedral, unless broadly enough conceived to include obedience, hierarchy, and veneration). Many of them blessed the young “liberty trees” planted on city and village squares all over France in the spring of 1848, bringing holy water and incense to a ritual celebration of republican values. The archbishop of Paris, Monsignor Denis Affre, remarked upon the “Christian courage” and “virile demeanor” of street fighters with rifles in shoulder belts who attended a mass for their slain comrades.†

This general enthusiasm did not survive a second, failed insurrection in June. The Constituent Assembly elected nationwide in April was a conservative body. When radical leaders demanded strong measures to alleviate the suffering of destitute Parisians, the Assembly demurred. The bourgeoisie saw socialism in the offing, and among churchmen who had recently trumpeted liberty, equality, and fraternity, equality no longer passed muster as a Christian truth. “All my political beliefs are shaken, not to say destroyed,” Montalembert wrote on the day a firebrand named Armand Barbès proposed extracting five billion francs in taxes from the rich. “I have devoted the twenty best years of my life to a chimera, to a transaction between the Church and the modern principle. … My ideas are not yet completely settled on this score, however. I am waiting. Pius IX’s example will guide me.” He would be guided more immediately by the death of Archbishop Affre, who along with two vicars presented himself at a barricade in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine during the June insurrection, hoping to mediate between combatants, and received a bullet in the back for his trouble. Thousands died.

As for the pope, in November 1848 his trusted minister of justice, Pellegrino Rossi, was killed by insurgents who besieged the Quirinal Palace, forcing Pius to seek refuge in the city of Gaeta and creating a Roman republic. Pius reestablished himself in Rome fourteen months later, with the help of a French expeditionary force. His politics had meanwhile changed: the former liberal had become even more unbendingly authoritarian than his predecessor. And in the newly elected president of the Republic, Napoléon’s nephew Louis-Napoléon, who was praised by the Catholic paper L’Ami de la religion as “the genius of strength and order … come to France’s rescue,” the pope’s worldview found an open ear. Parliament, largely a collection of conservatives horrified by the events of June 1848, might have scuttled the Republic right away had they not been divided among themselves—some wanting a constitutional monarchy to replace it, others a Bourbon restoration, and others still a Napoleonic empire.

In his memoirs, Alexis de Tocqueville observed that those deputies with whom he sat in the Assembly might have been spared their grief if, earlier on, they had been mindful of historical precedent. When aristocratic émigrés who had been libertines in their youth regained power twenty years after the Terror, they made sure to enthrone devoutness. In the same way, the irreligious middle classes of Louis-Philippe’s day discovered the social usefulness of ecclesiastical authority during the upheavals of 1848. With the ground quaking under them they looked for stability to the Church’s sacraments, hierarchy, and mores—and its pedagogical precepts. The philosopher Ernest Renan might scoff at the exercises in classical rhetoric devised by Jesuit masters, but for Tocqueville eloquence was a guarantor of civilization. It performed the function that ancient Roman custom assigned to oratio. It was political wisdom’s first defense against tyrannical wrath. Nothing distressed him more in the Constituent Assembly of 1848 than the crude language of revolutionary delegates, the so-called Montagnards. “For me it was like the discovery of a new world,” he wrote.

One consoles oneself for not knowing foreign lands by supposing that one knows one’s own country at least, and one is wrong; for there are always areas of one’s own land that one has not visited, and races of men who are new to one. I experienced this fully then. I felt that I was seeing these Montagnards for the first time, so greatly did their mores and way of speaking surprise me. They spoke a jargon that was not quite the language of the people, nor was it that of the literate, but that had the defects of both; it was full of coarse words and ambitious expressions. A constant jet of insulting or jocular interruptions poured down from the benches of the Mountain; they were continually making jokes or sententious comments; and they shifted from a very ribald tone of voice to one of great haughtiness. Obviously these people belonged neither in a tavern or in a drawing room; I think they must have polished their manners in the cafés and fed their minds on no literature but the newspapers.

The café invaded other European parliaments at a later date, to the chagrin of other statesmen. During the 1880s, Ernst von Plener, the leader of Austria’s Liberal Party, would have recognized in Tocqueville’s predicament a foreshadowing of his own exposure to vehement demagoguery. Appalled by Georg von Schönerer and Karl Lueger (Hitler’s political models), who filled the Reichsrat with coarse invective, he lamented “the barbarization of the parliamentary tone in our House of Representatives.”

As Tocqueville saw it, demagoguery would be the ultimate political expression of a society bereft—of family pride, manners, grammar, local custom, hierarchical structure, religious principles, and sacred space. “What now remains of those barriers which formerly arrested tyranny?” he asked in Democracy in America thirteen years before the 1848 Revolution. “Since religion has lost its dominion over the souls of men, the most prominent boundary that divided good from evil is overthrown, everything seems doubtful and indeterminate in the moral world; kings and nations are guided by chance, and none can say where are the natural limits of despotism and the bounds of license. Revolutions have forever destroyed the respect which surrounded the rulers of the state; and since they have been relieved from the burden of public esteem, princes may henceforward surrender themselves without fear to the intoxication of arbitrary power.”*

Tocqueville could not have failed to appreciate that the prodigious reconstruction of Paris during the 1850s and ‘60s intensified feelings of “indeterminacy” by destroying neighborhoods, abolishing familiar vistas, and estranging Parisians from their past. But it was the Communards’ secession that conformed most closely to his prophecy. Theirs was the “intoxication of arbitrary power.” Or so it seemed to conservatives for whom, during the 1870s, in the bloody wake of the Paris Commune, “moral order” became a motto. As much as the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, the Commune, short-lived though it was, demonstrated the fragility of venerable institutions.

Tocqueville was interned at Vincennes Prison in December 1851, when President Louis-Napoléon ended the Second Republic with a coup d’état. Other noncompliant legislators, Victor Hugo among them, fled the country. After having himself dubbed Napoléon III by plebiscite one year later, the usurper ruled very much to the advantage of the Church, which pledged fealty to him, as it had at first to the Republic. The Church grew richer and stronger during the Second Empire. Teaching orders thrived. Jesuits banished from France under Louis-Philippe now slipped back into the corridors of power. Intellectuals known for their positivist convictions were purged from the school system. Louis-Napoléon’s first minister of education abolished programs in history and philosophy but required high school students to be examined in religion. Lycées and universities scraped along on science. Necessity mothering invention may best explain the accomplishments of Louis Pasteur, the chemist Marcelin Berthelot, the physiologist Claude Bernard, and other great scientists who made their mark at this time. In 1858 Pasteur complained that not one farthing had been budgeted for the advancement of science through laboratory work. Bernard grimly observed that laboratories were the tombs of scientists.

This situation improved somewhat after 1859. When Louis-Napoléon defeated Austria at Solferino in that year—driving it out of the northern Italian territories it had controlled since Napoléon I’s downfall and leveling a formidable obstacle to the movement of national unification—his relations with Pius IX, whose temporal authority extended over one-third of the peninsula, deteriorated. Less reliant upon ecclesiastical support than at the time of his coup d’état, he seemed to rediscover the young exile who thirty years earlier had joined the Carbonari in Rome fighting against papal rule. Certainly, the Italian campaign announced a general liberalization of the Empire. While pious appearances were maintained, the spirit of scientific inquiry, like the language of political opposition, was given greater play. Thought that would have invited censorship before 1860 now dared to speak aloud, though still not always with complete impunity.

THE BATTLE LINE between champions and foes of the Enlightenment formed once again in bitter controversy over a book titled La Vie de Jésus, by Ernest Renan. Its publication, in 1863, four years after Darwin’s Origin of Species, was a momentous event.

Renan, who had come to Paris from Brittany destined for the priesthood, might have made a learned cleric had he not studied Semitic languages at the Saint-Sulpice seminary. There, his voracious intellect found nourishment in philology, and this disciplined study of texts, when applied to biblical exegesis, raised doubts that ultimately convinced him to defrock himself before his ordination. “I took the measure of which concessions the Church can make and those that must not be demanded of it,” he later wrote in his memoirs. “If the Church admitted that The Book of Daniel is an apocryphal text of the Maccabean era, it would be admitting error; if it had erred there, it might have erred elsewhere. It would no longer be divinely inspired.” The Catholicism bred in his bone—of Scripture, of the Councils and dogma—no longer sat right in his mind, and he began life anew, charting a secular course. “I thought it disrespectful of the faith to fiddle with it.”

Letters that attest to Renan’s loss of belief in divine revelation also document his precocious acquisition of mastery in the languages of biblical antiquity. On May 2, 1847, when he was twenty-four, the Institute of France (a cluster of learned societies including the French Academy) awarded Renan the Volney Prize for his Historical and Theoretical Essay on the Semitic Languages in General and the Hebrew Language in Particular. In 1848, amid revolutionary havoc, he earned an advanced degree in philosophy and completed a long essay called “L’Avenir de la science” (“The Future of Science”), which enunciated the intellectual creed by which he proposed to live. Devenir— historical development or flow, implying evolution—was now the conceptual basis of his scholarship, and he argued against obscurantists sworn to social and cultural absolutes. “The science of the human mind must above all be the history of the human mind, and only through patient, philological study of the works it has brought forth in different ages does that history become possible.”

Ernest Renan at the time of the publication of La Vie de Jésus.

Philological study fully occupied him during the 1850s, the first decade of Louis-Napoléon’s Second Empire. His contributions to learned journals ranged in subject from the religions of antiquity to the origins of Islamism. Before long Renan stood tall enough to be remarked by the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, which made him a member, and to be targeted by the Vatican, which put his critical study of the Book of Job on the papal index of prohibited publications. There was also ambivalent recognition from Napoléon III’s entourage. Empress Eugénie, a devout Catholic, did not welcome apostates, but he was admired by a small coterie to whom intellectual distinction meant something, and all the more so when it expressed itself with literary flair. A member of this coterie who wielded considerable influence at court arranged an archaeological tour of Palestine and Syria for Renan at state expense in 1860. It was during his sabbatical that he embarked upon La Vie de Jésus.

Since the 1830s, the life of Jesus had inspired a substantial body of erudite opinion across the Rhine at Tübingen University, most famously David Friedrich Strauss’s Das Leben Jesu (1835), which George Eliot translated into English and Émile Littré into French. In 1849 Renan, having thoroughly familiarized himself with German scholarship, published an essay titled “Les Historiens critiques de La Vie de Jésus.” His debt to Strauss, the Hegelian, is obvious—but so is his divergence from him, for while Strauss held that Jesus Christ was largely a mythical creation tailored to Old Testament figurations of the Messiah, Renan insisted upon his historical reality. Jesus the man required chronicling, and at twenty Renan may already have known that this would be his mission in life. At Saint-Sulpice he recorded a dream that seems to signal the future biographer. A sentence of death had been passed upon Jesus, he wrote. “No one present said anything, except me. I sprang forward and pleaded his cause. Some witnesses laughed, others were serious. I remember several phrases from my speech. I spoke about his youth, about his sweet, pure demeanor. I wanted him to love me. … Oh, Jesus, could I have denied you? The mere thought of it is painful. I must absolutely believe that you lived. … If I am to love you, you had to have been flesh and blood.”

The man pictured in La Vie de Jésus is a charismatic leader, a paragon of virtue, a Romantic hero scornful of the patriarchate, a prophet who believes himself to be the son of God. But he is no divinity. The new order he promises is a fullness of being that vanquishes death. But he dies. Renan shaped his work around the cultural rift, as he saw it, between Judea and Galilee. Among Judeans, an obsession with pedantic disputation had stifled communion with God and enslaved the spirit to ritual. Their leaders, the earthbound Pharisees, favored polished architectural vistas over God’s Creation. “[Jesus] called such showy architecture ‘realms of the world and all their glory,’” Renan wrote of Herod’s city, Sebaste (but thinking as well, perhaps, of Napoléon III’s new capital, rising over the rubble of medieval Paris). “This administrative and official art displeased him. What he loved were his Galilean villages, a jumble of huts, of basins and presses carved into the rock, of wells, tombs, fig and olive trees. He always remained near nature.”

Jesus, the village illuminato, descended upon Judea with no more regard for its hierarchies, laws, and mores than the wind of the wilderness. Renan infers from the Gospels and Saint Jerome’s commentary in Dialog! contra Pelagionos that blood relations meant little to a man, the “Son of God,” unloved by his family* Like all messianic ideologues, he recognized as kin only followers pledged to his Word. “We see him trampling underfoot everything human: blood, love, fatherland, and reserving heart and soul for precepts that embodied the good and the true.” In common with French revolutionaries who celebrated the birth of the Republic as Year 1, Jesus stood for fatherless dispensations. “Nowadays, man risks little and wins little,” wrote Renan, in language reminiscent of Pascal’s wager. “During the heroic ages of human activity, man risked everything and won everything. The good and the wicked, which is to say those who believe themselves good or wicked and are believed to be such by others, form enemy camps. Apotheosis is achieved on the scaffold; characters have features so sharp that they get etched into men’s memories as eternal types. Except for the French Revolution, no historical circumstance was more propitious than Jesus’s to the development of those hidden strengths that humanity deploys only in days of fever and peril.”

In short, Jesus was a man, but an incomparable man, with something of the magister ludi, whose one true miracle was the revolution he fostered.

Renan had portrayed Jesus this way a year before the publication of La Vie de Jésus, in his inaugural lecture as professor of Hebrew at the Collège de France, France’s most prestigious academic institution. His course was suspended immediately. The uproar that followed gave wings to his book. By 1865, one hundred thousand copies had been sold (this in an age of small editions, when the sale of five thousand would have been reckoned a success). No religious work had enjoyed such popularity since Luther’s day, asserted Renan’s friend Hippolyte Taine. The critic Sainte-Beuve blessed it. Writers of the Romantic generation, notably the great historian Jules Michelet, were lyrical in their praise. George Sand—who, in 1848, had joined the revolutionaries extolling Jesus the “democrat”—read Renan’s work as the trump of doom for Christianity. “Let’s accept the plain truth, even when it surprises us and changes our point of view,” she wrote to Prince Jérôme Bonaparte. “Jesus has been thoroughly demolished! So much the better for us perhaps.” In her opinion Christianity could no longer do anything but harm, and the book served an eminently useful purpose.*

On the other side, tracts and articles abounded, with La Vie de Jésus making rich pasture for theologians galled by its argument. Hate mail also rained upon Renan, much of it from parishioners who had heard his book damned at Sunday service. He was called a fool, a madman, a public poisoner, a mountebank, the scourge of the earth, Baron de Rothschild’s hired hand. “You great imposter!” one letter-writer exclaimed, with mandatory allusions to Judas Iscariot. “Lie down with your head in the dust; you who are nothing but ashes and dust, retract this impious work and confess your error. For it is known by everyone … that you wrote your infamous book to enrich yourself, like the traitor Judas who sold our Saviour to the Jews.” Enraged that he had turned his God-given gift of intellect against his divine benefactor, a countess declared that “the corruption flowing from your soul is even more hideous than its fleshly envelope, revoltingly ugly though that is.” Canon Lambert of Saint-Sulpice, whom Renan had known at seminary, threw La Vie de Jésus in the fire but assured him that there was still time to save himself from the flames. “Poor errant soul. Fallen angel, it isn’t too late, go back home to yourself. Should you sincerely re-enter the fold, you will be pardoned.” There was strong support in the conservative Senate for a bill banning Renan’s works, along with Voltaire’s, Rousseau’s, Sand’s, and Michelet’s, inter alios, from public libraries.

What abounded, besides vituperation, were miracles, many of them credulously reported by the ultraorthodox Catholic newspaper L’Univers. Pius IX’s pronouncement in 1854 that the Immaculate Conception was thenceforth to be official dogma had reinforced a cult of the Blessed Virgin, and La Vie de Jésus did nothing to arrest an outbreak of Mariophanies. In provincial France, apparitions were rampant, as was idol worship. On July 30, 1864, the archbishop of Avignon crowned a statue of the Virgin at a Vauclusian sanctuary called Notre-Dame de Lumières. The crowd of twenty thousand who gathered to witness the coronation acclaimed it with chants of “Long live Mary,” “Long live Notre-Dame de Lumières,” “Long live the Queen of Heaven and earth,” “Long live our Lord Bishops,” “Long live Pius IX.” Similar demonstrations took place not far away, at La Salette, where the Virgin, speaking in patois, had presented herself some years earlier to two young shepherds, and at Lourdes, where She had appeared to the illiterate daughter of poor millers.

An encyclical promulgated in 1864 by Pius IX, Quanta Cura, while making no special mention of La Vie de Jésus, was a global condemnation of the “depraved fictions of innovators” afflicting the modern world. It came with a list, or syllabus, of eighty “errors.” The last error of thought, epitomizing all eighty, was that “the Roman Pontiff can, and should, reconcile with progress, liberalism and modern civilization.” Pius ratified his predecessor’s contention that to regard freedom of conscience and worship as the inalienable right of every man was insanity (deliramentum). Only those who possessed the truth enjoyed freedom (a doctrine that recalls Robespierre’s invocation of the Supreme Being to legitimize “the despotism of liberty”). And what spelled insanity for individuals unanswerable to the moral authority of the only true church spelled revolution or unbridled materialism for society at large. “At this time there are found not a few who, applying to civil intercourse the impious and absurd principles of what they call Naturalism, dare teach ‘that the best form of Society, and the exigencies of civil progress, absolutely require human society to be constituted and governed without any regard whatsoever to Religion, as if this [Religion] did not even exist, or at least without making any distinction between true and false religions.’” Was it not plain, he asked, “that the society of man, freed from the bonds of Religion and of true justice, has no other purpose than the effort to obtain and accumulate wealth, and that in its actions the only law it follows is that of unrestrained cupidity, which seeks to secure its own pleasures and comforts?”

Deploring every change wrought by the scientific revolution, Pius chased from the temple not only money changers but also rationalists. Warped, he declared, is the notion that human reason, without any reference whatsoever to God, can be the sole arbiter of truth and falsehood, or of good and evil. Misguided are all who believe that divine revelation contributes nothing to the perfection of man. Radically in error is the contrarian brought before Pius’s inquisition who declares: “The prophecies and miracles set forth and recorded in the Holy Scriptures are the contrivance of poets, and the mysteries of the Christian faith are the result of philosophical investigations. In the books of the Old and the New Testament there are contained mythical inventions, and Jesus Christ is Himself a myth.” What follows is the dangerous belief (Error no. 47) that public schools intended for instruction in letters and “philosophical sciences” should function without ecclesiastical interference.

Pius’s bulls became more vehement as the territories over which popes had exercised temporal authority since Charlemagne’s day—the whole midsection of Italy, from Ravenna to Rome—began to shrink. We have seen how France was implicated in this contraction. By expelling Austria from Lombardy-Venetia in 1859, it removed a major obstacle to the unification of Italy under the Piedmontese prince Victor Emmanuel II. What is more, French troops garrisoned in Rome since 1849 to protect Pius against republican insurgents did not intervene when rebels in Romagna, a papal state, overturned the pope’s feudal government. Pamphlets justifying the emperor’s quiescence with the argument that the pope’s temporal loss had only increased his spiritual stature offended militants in France. Quiescent he remained while two more papal states, the Marches and Umbria, joined the Risorgimento. “Your emperor is a deceitful rogue,” Pius told the French ambassador, an opinion seconded by ultramontane loyalists such as Louis Veuillot, who edited L’Univers. A convert, Veuillot took pride in being plus catholique que le pape and even more pugnacious.

The Syllabus of Errors was the roar of a beleaguered Vatican.* Witnesses describe Pius in his private chapel, praying for hours on end. At war with a world whose rulers he could no longer best, he came increasingly to believe that his decisions were divinely inspired, or had to be understood as such. In Quanta Cura he had claimed plenary power “conferred on the Sovereign Pontiff by Jesus Christ” to guide and supervise “the Universal Church.” Five years later, in 1869, a Vatican Council elaborately staged by his prefect of propaganda collaborated in the ultimate exaltation of pontifical power. Bishops who had come from as far away as India, China, and the South Sea Islands (rather like the heads of state who had recently assembled in Paris for a universal exposition) spent seven months together and at last, in July 1870, after much lucubrating over less significant matters, proclaimed the infallibility of the pope. The supernatural privilege of never erring in ex cathedra pronouncements about the faith and morals had been accorded Jesus’ surrogate.

Not every French bishop at the Council voted placet, or yea. But “anti-infallibilists,” as they were known, often found themselves snubbed when they returned to their flock. Given a choice between the Roman and French (“Gallican”) liturgies, eighty of ninety-one dioceses chose the former. In much of Catholic France, Pius IX wore a martyr’s halo for having been divested of the Papal States, and his theological Luddism burnished his image. L’Univers described the pope as Christ on earth. One high-ranking clergyman preached that the Son of God was incarnate in the Virgin’s womb, in the Eucharist, and in Pius. With few exceptions, parish priests followed him obediently. Charles de Montalembert, who no longer took his cues from Rome, complained that the pope had become an idol, and reason and history, truth and justice were being immolated in his name. “The history of the Church presents mysteries in great profusion,” he wrote, “but I don’t know any that equals or surpasses the extraordinarily sudden transformation of Catholic France into a farmyard of the Vatican.” Reacting to this groundswell of religious zeal, Gustave Flaubert declared that the really decisive issue for France was neither the prospect of war with Prussia nor the enfeeblement of Napoléon III. The only important thing, he wrote, was religion, or clericalism (meaning the role of the Church in political life). “We must no longer dream about the best form of government … but of seeing to it that Science rules.” It seemed to him entirely possible that France, like Belgium, might end up divided into two parts, with Catholics here and the secular-minded there.

FRANCE’S INTERNAL DIVISIONS found a new theater in which to speak when, only days after the proclamation of papal infallibility, war broke out with Germany. Since 1866 Otto von Bismarck, the Prussian prime minister, whose grand design was to forge a German Empire in the heat of war, with Wilhelm of Prussia as its sovereign, had been carefully devising a casus belli against France. History abetted him when the Spanish throne fell vacant. Bismarck persuaded King Wilhelm’s relative Prince Leopold of Hohenzollern to present his candidacy, knowing full well that France could not allow itself to be pinned between two of that family. Leopold subsequently withdrew his bid at Wilhelm’s urging, but his gesture did not mollify France’s foreign minister, the Duc de Gramont, who insisted that Leopold should never again be allowed to come forward. Wilhelm refused, and the matter might have rested there had Bismarck not made the refusal sound contemptuous by mischievously editing a telegram from Wilhelm to Louis-Napoléon. Inflamed by the press, which geneally denounced Prussia’s “slap in the face,” Frenchmen mobbed the streets of Paris. On July 14, 1870, an order to mobilize was issued. Two days later, deputies voted funds for war, with only 10 of 255 in parliament dissenting. The huge crowd outside the Palais Bourbon was jubilant. One witness thought that the scene might have been not much different at the Colosseum in Rome when frenzied spectators climbed the Vestals’ tribune to demand the execution of a gladiator, little realizing that France herself was the doomed combatant.

Gramont, a militant Catholic, may have been animated by hatred of Protestant Prussia. In any case, war had no sooner erupted than it spilled into the realm of religious politics. French pontifical troops garrisoned in Rome, the last enclave of papal power, were immediately pulled from the city to join battle with Germany. As a result nothing impeded the triumphal entry of Victor Emmanuel’s army. Although Gramont declared that France could not lose its honor on the Tiber (by leaving the pope undefended) and preserve it on the Rhine, his well-turned phrase rang hollow, for it quickly became evident that Louis-Napoléon’s army was outnumbered, outgeneraled, and outgunned. On September 1, some six weeks after hostilities began, the emperor, under relentless German shell fire, hoisted a white flag over the river town of Sedan. On September 20 the pope, also under shell fire, hoisted a white flag over the Castel Sant’ Angelo. While Louis-Napoléon was abdicating in the Ardennes, Pius IX was declaring himself a prisoner in the Vatican. To French no less distressed by the fall of Rome than by the prospect of enemy troops besieging Paris, it was the consummation of the pope’s martyrdom.”Let us pray that God hasten the moment when France, delivered from the Prussians, but above all from itself, shall deliver Rome from the Italian slough and restore to degraded humankind a God-given benefaction it cannot forsake without perishing,” wrote Louis Veuillot. The “Government of National Defense” formed by republicans on September 4 deepened his gloom.

God was in no rush to deliver France from the foreign enemy or from the enemy within, though it seemed for a moment that Veuillot’s prayers had been answered. There would be far more killing, of French by Germans, and of French by one another.

HAVING QUICKLY FOUGHT through the Vosges mountains and occupied the belt of country between Alsace-Lorraine and the Île-de-France, General Helmuth von Moltke felt certain that his men could safely camp around Paris until the besieged city surrendered to hunger. Neither he nor Bismarck anticipated one of the more valiant second efforts in the history of warfare. On October 7, 1870, Léon Gambetta, a dynamic orator serving as minister of the interior in the Government of National Defense, escaped from Paris by balloon. He joined fellow ministers at Tours, and improvised a whole new army, the Army of the Loire, which proceeded to drive German troops out of Orléans. Alarm spread all along the enemy line. The Loire valley now became a war theater, forcing France’s extramural government to relocate farther south, in Bordeaux.

But victory along the Loire was a small candle in the gathering night. For many, it flickered out on October 27 when a French army trapped inside the fortress-city of Metz surrendered, freeing large German divisions to serve elsewhere. The ill-trained French often acquitted themselves well, but theirs were campaigns of heroic futility. The siege had reduced Parisians to starvation. Krupp cannons kept lofting shells into the capital from miles away, and German forces marched inexorably down the Seine valley. On January 17, 1871, the last army corps patched together under Gambetta’s provincial administration was defeated near Belfort, between the rivers Rhine and Rhône. Over 150,000 Frenchmen had given their lives since July, in what the historian Michael Howard has called the world’s first total war. On January 28, after several weeks of secret shuttling between Paris and Versailles, where Bismarck had established German headquarters, Jules Favre, minister of foreign affairs (one of those ministers who had not escaped from Paris), negotiated an armistice. Its central provision was that France, in free elections, should form a government with which Germany could treat. By then, implacable resistance to the Germans was the position of only isolated groups: notably, working-class Parisians. Most French wanted peace. Gambetta, honoring, à contre coeur, what he acknowledged to be the general will, resigned his ministry. Up north, wagons laden with food entered Paris, which surrendered the perimeter forts.

Early in February, Paris invaded Bordeaux, or so it seemed when journalists, power brokers, actresses, and boulevardiers flocked south, some to observe the newly elected Assembly, others to convalesce. Bordeaux’s population grew hourly, and almost all the deputies arrived before the inaugural session. One who didn’t was Victor Hugo. Hailed en route from Paris by crowds shouting, “Vive Victor Hugo! Vive la République!,” Hugo met even larger crowds in Bordeaux, where, he, Gambetta, and the future prime minister Georges Clemenceau, among others, joined against conservatives eager to buy peace at any price. They were a minority within parliament, but these republican stalwarts found support outside it among Bordelais whose demonstrations became so boisterous that light infantry and horse guards were summoned to patrol the streets. The horse guards closed ranks on February 28, when Adolphe Thiers—elected chief executive ten days earlier with a mandate to negotiate a peace treaty at Versailles—set forth Bismarck’s draconian terms. By evening it was common knowledge that Germany wanted most of Alsace and part of Lorraine. Furthermore, German troops would occupy French territory until France had paid reparations in the amount of five billion francs. On March 1, after hearing eloquent protests, the legislature yielded. “Today a tragic session,” Hugo wrote in his diary. “First the Empire was executed, then, alas, France herself!”

At its penultimate meeting in Bordeaux, the Asssembly, led by a conservative majority who feared Paris—where three revolutions had taken place sinced 1789—voted to reconvene on March 20 at the palace of Versailles.

Governing from Versailles conveyed a political message distasteful to republicans. But of greater immediate consequence was the Assembly’s decision to end two moratoria that had eased the pain of Parisians trapped and unemployed since September 1870: one suspending payment due on promissory notes, the other deferring house rent. The measures restoring their obligations promised further hardship to several hundred thousand inhabitants of an economic wasteland and alienated the capital en masse. Debt-encumbered shopkeepers, idle workers, and artisans whose tools were in hock made common cause against an enemy all the more vengeful for being French. Indeed, the German soldiers camped outside Paris became mere spectators, as hatred of the foreigner turned inward.

The legislature might not have been so obdurate had Paris not previously challenged its authority. After the elections of February 8, republicans in Paris had presumed that the Assembly’s conservative majority—provincial deputies for the most part—were determined to restore throne and altar, and their anger voiced itself through the National Guard, a democratized version of the bourgeois militia founded in 1789. It became a quasi-political organism, and on February 24 delegates from two hundred battalions ratified a proposal to replace the centralized state of France with separate autonomous entities—confederated “collectivities.”

For Thiers, reports of troops breaking ranks all over town brought back memories of February 1848. At that time he had urged Louis-Philippe to leave Paris and recapture it from without, but the king had rejected his advice. This time, God alone stood above him. As soon as he had left the city, he issued general evacuation orders. Forty thousand army regulars were thus marched out of Paris, never to serve again. Up from the provinces came fresh conscripts “uncontami-nated” by the capital, and before long one hundred thousand men occupied camps around Versailles. The day of reckoning was imminent, Thiers proclaimed on March 20. Forty-eight hours later, Versailles accepted the role Germany had played several months earlier. It declared Paris under siege once again.

In the city, forsaken ministries were staffed by tyros who somehow improvised essential services. The National Guard’s Central Committee served, perforce, as an alternative government, though its avowed program was to organize elections for a Communal Council, then dissolve itself. Elections took place on March 26 and produced a council with very few moderate members, most of whom resigned straightaway. This left the high ground to extremists, whose abhorrence of a government that had in their judgment traded honor for peace intensified their visions of a new political and social order. On March 28, in front of City Hall, Paris proclaimed itself a Commune. Newly elected councillors all wore red sashes. They stood under a canopy surmounted by a bust of the Republic, draped in red. A red flag flew overhead. Forming up to music first heard during the 1789 Revolution, National Guard battalions played the “Marseillaise” as people sang and cannon fired salvos.

In Versailles it was clear that a policy of conciliation with the Communards would find few friends right of center. Given a choice between force and pragmatism, legislators chose inaction. “Meeting follows meeting, and emptiness yawns ever wider,” Émile Zola despaired. “The majority will brook no mention of Paris. … This is a firm resolve: Paris doesn’t exist for them, and its nonexistence sums up their political agenda.” Zola, a parliamentary reporter for La Cloche, a Parisian newspaper, regretfully informed readers that in Versailles Paris seeemed very far away. “People there imagine our poor metropolis swarming with bandits, all indiscriminately fit to gun down.”

Paris needed no instruction from Versailles in the art of gross political caricature, and neutral parties had reason to observe that Communards were spoiling for Armageddon as fervently as right-wing deputies. A movement whose initial goal had been municipal independence soon consecrated the schism between the ancien régime and the new order. “The communal revolution … inaugurates a new era of scientific, positive, experimental politics,” the Commune proclaimed on April 19 (in a manifesto fraught with terms used elsewhere by writers seeking to legitimize “naturalist” fiction).

It is doomsday for the old governmental and clerical world, for militarism, bureaucracy, exploitation, speculation, monopolies, privileges to which the proletariat owes its servitude and the nation its disasters. May this great, beloved country deceived by lies and calumnies reassure itself! The struggle between Paris and Versailles is of a kind that cannot end in illusory compromises.

Throughout April, decrees rained thick and fast in Paris. Rent unpaid since October 1870 was canceled. The grace period on overdue bills was extended three years. Newspapers hostile to the Commune, including Veuillot’s L’Univers, were suppressed. Church was separated from State and mortmain property nationalized. The corridors and wards of the largest city hospital, the Hôtel-Dieu, were “debaptized.” And anticlericalism demanded the secularizing of education. A petition from “The New Education Society,” whose advice was not ignored, besought the Commune to “immediately and radically” suppress religious instruction, for both sexes, in schools supported by the taxpayer. “Liturgical objects and religious images should be removed from public view. Neither prayers, nor dogma, nor anything that pertains to the individual conscience should be taught or practiced in common.” (As priests and nuns were religious images incarnate, most removed themselves from the classroom.) Only one educational method should hold sway, “the experimental or scientific, which is based upon the observation of facts, whatever their nature—physical, moral, intellectual.”

Aggrieved Catholics wondered whether France would ever be “delivered from itself,” as Veuillot put it, or whether Pius IX’s banishment from Rome had only augured a kindred fate for them. All over Paris, churches were converted into political clubhouses, arsenals, or military posts. Some resisted. The congregation at one large church fended off the National Guard as best it could, opposing the “Marseillaise” with a rendition of the “Magnificat.” But resistance was hopeless. In festivities at the Panthéon, a large wooden cross with its arms sawed off became a mast for the red flag.* In the verbal scrum of club meetings, participants won attention by proclaiming their atheism. Sacrilege served as popular entertainment. In Saint-Sulpice, the crowd applauded a speaker holding an icon who defied God to stay his hand when he plunged a knife into Christ’s sacred heart. At Saint-Germain l’Auxerrois, which housed a revered statue of the Virgin and Child, a militiaman punched open the Virgin’s mouth, inserted a pipe, detached the infant Jesus, and marched him around on the end of his bayonet—all to frenzied cheers from the crowd. A woman at Saint-Nicolas des Champs proposed that the Commune reinforce Paris’s defensive wall with gunnysacks containing the bodies of the sixty thousand priests (by her delirious count) still present in the city. Another woman urged that nuns accused of poisoning hospitalized Communards be drowned in the Seine. Some sisters were forced to wear red sashes over their black habits.

In Louis Veuillot’s view, the demon possessing his compatriots could be exorcized only by fasting and prayer, and the French wanted a man of God to cure their ills, not a politician or a man of war. “We all know it, and we all exclaim: Perimus! But such is the depth of our illness that no one dares to say: Domine, salva nos! And the storm will toss our poor, foundering bark as it will. How sad, this people without God!” One might have expected more muscular sentiments from a writer who several months earlier had hailed King Wilhelm of Prussia as a divinely ordained instrument punishing “France the courtesan” for her dissoluteness.

But to subdue the Communards, Versailles called upon a man of war, not a man of God. It marshaled its battalions—as announced by Thiers on March 20—under General Patrice de MacMahon, whose army had surrendered at Sedan. What followed was a week of slaughter and arson commemorated in historical accounts as la semaine sanglante, “bloody week.” On May 21, government troops poured through five gates and swept across western Paris in pincer columns. Had MacMahon, who set up headquarters on the heights of Passy, known that the Commune’s only serious preparation for urban warfare was an immense barricade on the place de la Concorde, his army might have taken City Hall by dusk. Instead it regrouped after its headlong advance, giving the populous quarters time to fortify themselves. Several hundred barricades rose overnight, and the Versaillais fought their way eastward, street by street, as fires set to impede them or to gut abhorrent monuments raged out of control. The Tuileries Palace was soon ablaze, then the entire rue de Rivoli, the Ministry of Finance, the Palais de Justice, the Prefecture of Police, the three-hundred-year-old Hôtel de Ville. Paul Verlaine, who lived on the quai de la Tournelle, across the Seine from City Hall, witnessed this conflagration.

[I saw] a thin column of black smoke come out of the campanile of the Hôtel de Ville, and after two or three minutes at most, all the windows of the monument exploded, releasing enormous flames, and the roof fell in with an immense fountain of sparks. This fire lasted until the evening, and then assumed the form of a colossal brazier; this in turn became, for days after, a gigantic smoldering ember. And the spectacle, horribly beautiful, was continued at night by the cannonade from the hills of Mont-martre, which from nine that night to three in the morning provided a fireworks display such as had never been seen.

Before long spectators saw the July Column, which had been festooned with wreaths and flags, burning like a torch over the doomed Faubourg Saint-Antoine.* By Saturday, May 27, all that remained unconquered of Paris was its northeast corner. Caught between implacable Versaillais and German troops camped on the city’s perimeter, many National Guards drew their last breath during a skirmish in Père Lachaise Cemetery. Those who didn’t fall among the mausolea were lined up against a wall known ever since as “the wall of federals,” shot, and thrown into a common pit. Outside Père Lachaise, evidence was flagrant of a much greater hecatomb. Corpses lay strewn behind ruined barricades, against walls, on the riverbanks. Thousands had been given summary justice and brought before execution squads. Blood ran down gutters, coloring the Seine red.

Fifty-six hostages held by the Commune died between May 21 and May 29. They included Jesuits, Dominicans, and, most prominently, Georges Darboy, archbishop of Paris. Darboy might have survived if Versailles had agreed to exchange him for a prisoner the Communards lionized, the radical thinker Auguste Blanqui. Darboy himself petitioned Thiers, arguing that the exchange would involve “only people, not principles.” But Thiers stood on principle, and Darboy, a Gallican anti-infallibilist who had once been reprimanded for blessing the coffin of the Grand Master of the Freemasons, enjoyed little sympathy from right-wing deputies in a conservative parliament. Representations made by the American ambassador, Elihu Washburne, went unheeded. On May 24, Darboy was taken from La Roquette Prison and shot dead. On his chest he wore the cross of Denis Affre, the archbishop who had died during the Revolution of 1848 while trying to mediate at a barricade. On the hand that blessed his executioners he wore the ring of Monsignor Sibour, an archbishop assassinated in 1857.

Ten days after the conquest of Paris, Darboy’s coffin, preceded by a standard-bearer and followed by a delegation from the National Assembly—which had not saved him when it could have—was carried to Notre-Dame cathedral. In Louis Veuillot’s eyes, the funeral was a triumphal march. “The cross, banished for nine months … demands and reclaims its right through martyrdom,” he asserted. “It is summoned by the voice of blood and of testimony. One must yield, God wills it. The barricades are coming down; the savage’s passion is under control; and the cross is borne aloft. … Tomorrow you will do as you please, you will understand or you won’t, you will follow a new path or resume your evil ways. But here is a martyr, and you will let the cross pass by.”*

Even more hortatory was Pius IX’s foremost episcopal advocate, Bishop Louis-Édouard-Désiré Pie of Poitiers, who wanted Paris to throw off its mourning clothes and greet an era of national regeneration. The myriad dead had been a “sacrifice.” The civil war was likened to the Great Flood inflicted on sinful humanity. Arising from it was a “sweet savor” agreeable to the Lord, who would now, he hoped, establish his covenant with France. “Above the bloody scenes of la Roquette one saw a rainbow portending better days.” To be sure, Monsignor Darboy had not been above reproach, Pie wrote in a pastoral letter, but the “bloody scythe” of death had pruned him of unseemly growth. His death was impeccable.

The nation that emerged from civil war put few people in mind of Noah’s Ark securely perched on Mount Ararat. It remained a house divided: equivocating over its political identity, either vilifying or glorifying its past, and finding devils under its own roof. “Regeneration” was everyone’s slogan, but pinned to it were very different meanings. For some it meant the embrace of science. For others it entailed rituals of purging and contrition. When a prominent republican consoled himself with the thought that such ordeals as society had endured might have “transfigured” it, Bishop Pie noted that change would be for the better only if it brought a change of “doctrine.” France, the revolutionary “tool of Satan,” had once more to become “the soldier of Christ.” Possessed by an imposter since 1789, it had to recover its true self.

AN OBSERVANT TOURIST would have found ample evidence to support the view that God seemed happier in France during the early 1870s than He had been for some time. Many young people took holy orders after the war, much as they had after Waterloo during the Bourbon Restoration. Though money was scarce, hard-up congregants still paid Peter’s pence—a voluntary contribution made annually to the pope. In 1872, the Assumptionists (or Augustinians of the Assumption) organized a league—the Association Notre-Dame du Salut—whose mission was the salvation of France through prayer. And a weekly magazine they launched on July 12, 1873, became the vade mecum of French pilgrims. Vendors of religious statuary drove a thriving trade. Dom Guéranger’s efforts to revive plainsong at the abbey of Solesmes yielded Les Mélodies grégoriennes in 1880. Choral societies flourished. Country churches and presbyteries multiplied. Saintly patronage spread. Having been proclaimed “a patron of the Catholic Church” by Pius IX in 1870, Saint Joseph, Mary’s humble consort, became the tutelary spirit of family men, carpenters, Christian spouses, primary school teachers, the exiled and deported, missionaries, and “people given to the inner life.” Saint Philomena, Saint Anthony of Padua, Saint Roch, Saint Germaine Cousin sat on prayerful lips. Queen Radegund, a Merovingian saint better known in England than in France, acquired national celebrity when train passengers bound for Lourdes began to make a point of invoking her aid during their stopover at Poitiers.* At Tours, flanked by soldiers, they ritually paraded down the main street under a banner of Saint Martin chanting “Sauvez Rome et la France au nom du Sacré-Coeur.” On a twenty-hour voyage to Lourdes from Avignon in 1874, pilgrims took turns reciting the rosary around the clock, their ecclesiastical travel agent having assigned each train compartment a precise timetable of recitation before departure.

This postwar revival, whose intense emotionalism harked back to the Counter-Reformation, benefited from the industrial age. Notwithstanding Pius IX’s indictment of all things modern in The Syllabus of Errors, rapid transportation enabled the devout to make their presence felt en masse. There were spectacular assemblies, and 1873 was a notable year for them. The faithful gathered in their thousands to hear apocalyptic homilies at Lourdes, at Mont Saint-Michel, at La Salette, at Sainte-Anne d’Auray. National salvation was the issue, Monsignor Pie declared on May 28 at Chartres, where his huge audience, spilling beyond the cathedral, included forty bishops, one hundred forty legislators, and military officers of every rank. “To what state of prostration and impotence has public society been reduced among us? By what means can we wrest ourselves free from this despondency?” he asked. With “the rights of God” subverted by idolators extolling natural law, no wonder parliament couldn’t decide whether France was fish or fowl, a republic or a monarchy. Nations that spurned the principle of Christian authority always lost their way. “We go in circles, we flail about at an impasse: In circuitu ambulant, effusa est contemptio super principes, et errare fecit eos in invio et non in via.”† One month later, many of these same pilgrims, heeding Pie’s exhortation, gathered at Paray-le-Monial, in the great Cluniac basilica of the Sacred Heart, to hear another bishop deliver much the same message. “Since you have reconvened at Versailles,” he said, addressing the politicians present, “you have often asked God to forgive France her crimes. You have often made honorable amends to the Sacred Heart of Jesus for the ingratitude we have repeatedly shown, especially during the past eighty years” (in 1793 the royal family was guillotined). In an unopposed proclamation, assurances were given to Pius IX that the French stood foursquare behind “the courageous Syllabus.”

Responsible for killing a king and deserting a pope, the French were thus reminded that they had sins of parricide to expiate. Mea culpas had begun ringing out even before the execution of Archbishop Darboy. On May 14, 1871, when Communards still held Paris, the National Assembly in Versailles agreed by majority vote that the public should pray for divine leniency. “Long have we been oblivious of God,” it declared. “It behooves this truly French Assembly to repair our lapse and show the world that France at last recognizes the only hand able to cure and save her.” The words “Lord, we are a guilty, woeful country” echoed through every parish, voicing the conviction that moral deliquency and military unsuccess went hand in hand. Countless articles exploited this penitential axiom after the war. The conservative newspaper Le Figaro pointed out that the first defeats inflicted by Prussia, at Wissembourg and Reischoffen, had coincided with the removal of French Zouaves from Rome.

The zeal that raised money for chapels throughout France also inspired plans for a national shrine in Paris. Under Bishop Pie’s aegis, this idea was promoted during the winter of 1870 and ‘71 and found favor with Catholics everywhere. When Pius IX blessed the project, Monsignor Guibert, archbishop of Paris, lost no time formulating its raison d’être, mobilizing support, and raising money. At stake was the re-Christianization of his godforsaken country, and the shrine—a grandiose monument as Guibert envisioned it—would display France’s magnificent humility. It would be called the basilica of the Sacred Heart, in honor of a special devotion founded in the seventeenth century by the ascetic French nun Marguerite Marie Alacoque, whose visions of Christ’s heart burning with divine love had commanded her to establish “a feast of reparation” on the Friday after the octave of Corpus Christi.

This cult had provided more martyrs to the eighteenth-century Revolution than almost any other. “It was from France that the evil that has caused us such anguish spread across Europe,” Guibert declared privately, “[and] from France, birthplace of special devotion to the Sacred Heart, will come the prayers that lift us up and save us.” But no less symbolic than its name was its site. In October 1872, Archbishop Guibert reconnoitered Montmartre—the Mount of Martyrs in Catholic etymology—for some lofty real estate. Like Balzac’s Eugène de Rastignac, the hero of Pére Goriot, shouting “À nous deux!” from the nearby hill of Père Lachaise Cemetery, Guibert was bent on lording it over Paris. Unlike Rastignac, a consummate arriviste who rushed downhill to duel high society on its own ground in the Faubourg Saint-Germain, the archbishop made his stand up above. The Sacré-Coeur would be a sanctuary for refugees from Babylon, a Parisian home for a devotion of specifically French origin, a monument embodying allegiance to the pope cruelly separated from his seat in Rome, a majestic response to such pleasure domes as Charles Garnier’s neo-baroque opera house, and insurance against further punishment by a wrathful god. It would be, said Guibert, “a lightning-rod on the highest point of the capital.”

Still, the Church could not stake its claim and begin construction until the powers that be at Versailles deliberated, for expropriating landowners required legislative approval. Whether the project benefited the general public was the question, and because “benefit” lent itself to partisan judgment, Guibert couched his proposal in conciliatory terms, raising the flag somewhat higher than the cross. Who did not want France to knit together again? Portrayed as a patriotic omphalos, the basilica was deemed “publicly useful” by parliament, but not without clashes that might have been avoided if zealous members of the conservative majority had imitated the archbishop’s tact. Most zealous of all were Émile Keller and Gabriel de Belcastel, two deputies who passionately conflated Church and State. After noting the almost unanimous acceptance of a statement that the construction of the proposed church served a public need, Belcastel went on, “But our committee, endorsing the patriotism and faith that inspired the project’s sponsors, considers itself entitled and obliged to … add these words: ‘ … its purpose being to draw divine mercy and protection upon France and upon the capital.’” While private faith is the wellspring of great virtues, he declared, the honor and mainstay of a civilized nation reside in the public profession of faith. “Must one drum these things into French ears, into Christian ears? Gentlemen, France was born on a battlefield, by an act of faith.”

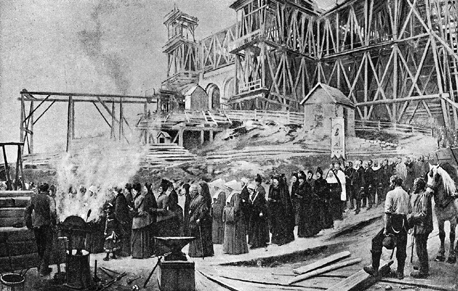

“Le Cantique,” by Jean Béraud, at the building site of the Sacré-Coeur, 1887, twelve years after the laying of the first stone. Marguerite Marie Alacoque, who inspired the devotion to the Sacred Heart in its modern form, wrote many “canticles,” or songs of praise. They were collected and published in 1867.

One rebuttal came from Edmond de Pressensé, a well-known Protestant divine and scholar of Church history, whose son, Francis de Pressensé, would, two decades later, figure prominently in the passage of legislation separating Church and State. He contended that while France might have been born on a battlefield by an act of faith, the National Assembly was born to debate political issues, not matters of conscience, which one sorted out alone with one’s God. Invoking divine mercy exasperated him most of all because it concealed, in his view, an attempt to establish the Sacred Heart as a state cult.* Another deputy put it even more bluntly. “What I object to is the confusion of two very distinct orders, the temporal and the spiritual, the State’s jurisdiction and the Church’s, the duties of civil society and those of religious society. I object to a bill that confers upon the State what belongs to the Church and upon the Church what belongs to the State.”

In the end, parliament compromised. It passed a safely bland proposal. But Pastor Pressensé’s suspicions had been well founded. Shortly before the vote was taken, Belcastel rescued his deleted rhetoric at Paray-le-Monial (where Marguerite Marie Alacoque had made her home, in the Convent of the Visitation), addressing some twenty thousand pilgrims. In a statement hailed by one hundred fifty or more like-minded legislators, he consecrated France to the Sacré-Coeur.

The Sacred Heart, in Saint Marguerite Marie Alacoque’s vision, asked her to build a chapel. Archbishop Guibert’s dream of Catholicism sponsoring a revival of the national soul demanded something much larger. All seventy or more structures proposed in an open competition were very large indeed, and especially the winning design. Surmounted by ovoid domes and cupolas of Romano-Byzantine inspiration, and striped from base to lanterns with dark stone ribs, it looked like a giant Turkish folly. Or so said its critics.* Criticism left the archbishop unfazed, however. What did trouble him was the discovery that tunnels for mining plaster riddled Montmartre. Engineers explained that a massively heavy edifice would collapse sooner rather than later. After much anguished deliberation, they hit upon the idea of seating the church on eighty stone pilings driven deep into the bedrock. The indomitable Guibert approved, and soon, with its underground stilts in place, the Sacré-Coeur began rising over Paris. Few who saw the foundation stone placed would be alive to celebrate the consecration of the basilica forty-four years later.

The laying of the first stone took place on June 16, 1875, in a ceremony witnessed by the papal nuncio, a contingent of papal Zouaves, nine bishops, and two hundred members of the National Assembly. Although Guibert had wanted every French bishop at his side, prudence called for less pomp. Several days earlier, the speaker at a gathering of Catholic charitable societies was reported to have prophesied that the foundation stone would mark the grave of “the principles of 1789.”

A funeral for those principles was the recurrent dream of hard-core monarchists among the many deputies in attendance. They had already tried and failed to bury the Republic, as we shall see, but hope sprang eternal.

*Le pays légal described the several hundred thousand citizens in a population of over thirty million whose status as taxpayers entitled them to vote and run for office.

* To be sure, there were regions intransigeantly hostile to the Church. During the Revolution of 1848, villagers in the Auvergne expelled priests known to have royalist sympathies.

* When Ozanam launched a newspaper called The New Era (L’Ére nouvelle) in April 1848 with Jean-Baptiste Henri Lacordaire, a Dominican priest who was among the greatest pulpit orators of the nineteenth century, the prospectus included this: “There are two forces in France: the people and Jesus Christ. If they separate, we are lost; if they join, we are saved.”

† Monsignor Affre’s warm embrace had a precedent in the so-called baiser Lamourette of 1792. Responding to the exhortation of a revolutionary bishop aptly named Lamourette that they “form themselves into one and the same body of free men,” otherwise factious legislators leaped to their feet, in Louis XVI’s presence, and kissed one another.

* Another threat to those moral barriers that formerly arrested tyranny made itself known to Tocqueville in Essay on the Inequality of Human Races, a pseudo-scientific thesis written by Arthur de Gobineau, who had served as his principal private secretary in the Foreign Office in 1849. Published between 1853 and 1855, Essay became the locus classicus of racial nationalism in fin-de-siècle France and twentieth-century Germany. Tocqueville told Gobineau, with whom he corresponded prolifically, that the doctrine of Aryan superiority erased all moral boundaries and paved the way to social hell. “Do you not see that your doctrine leads naturally to all the ills to which permanent inequality gives rise: pride, violence, contempt for one’s fellow man, tyranny, and abjection in all its forms?” he declared in November 1853. “Your doctrine and mine are intellectually worlds apart.” Gobineau’s was, he wrote, false and pernicious. It was the theory of a horse trader rather than a statesman.

* Among other citations, Renan refers to Mark 6:4 (“But Jesus said unto them: A prophet is not without honor, but in his own country, and among his own kin, and in his own house.”) and to John’s account of the marriage in Cana, 2:3-4 (“And when they wanted wine, the mother of Jesus saith unto him, They have no wine. Jesus saith unto her, Woman, what have I to do with thee? Mine hour is not yet come”).

* Renan himself felt, at that point in his life, that France was well served by religious principles inculcated in “the mass of the people;” that the latter would otherwise show a disinclination to subordinate the “will of the individual” to the order and welfare of society.

* E. E. Y. Hales, in a biography sympathetic to Pius, explains him as follows: “In his experience, the claim for liberties, not necessarily in themselves harmful, led in fact to Mazzini’s Religion of Humanity and to the persecutions of Turin [Victor Emmanuel’s realm]. ‘Liberty, Progress, and Recent Civilisation,’ in their Italian guise—the guise in which the Pope had met them—meant something which the Church could not tolerate.”

* The Panthéon had been built as a church during the ancien régime—the Église Sainte-Geneviève—but was deconsecrated during the Revolution. Thereafter its name and status changed with successive regimes. It was the Église Sainte-Geneviève during the Restoration of 1814-30 and the reign of Napoléon III (1852-70) but the Panthéon under Louis-Philippe (1830-48). It became the Panthéon again in 1885, to receive the mortal remains of Victor Hugo.

* The July Column had been erected on the place de la Bastille to commemorate the Revolution of 1830. The remains of more than five hundred revolutionaries lay in its base.

* At the same time, in Berlin, Bismarck, the German generals, and Kaiser Wilhelm—all on horseback—led a victory parade of forty-two thousand troops, replete with triumphal arches.

* Aristocratic ladies organized a welcome committee to demonstrate “the traditions of chivalric devotion.”

† The quotation, beginning with “effusa est,” is from Psalm 107: “He brings princes into contempt and leaves them to wander in a trackless waste.”

* Before national elections in 1873, the Church had called for “a crusade of prayers” in the name of the Sacred Heart, to guarantee “good results,” meaning a parliament of legitimists pledged to restore the monarchy.

* By the end of the century it had been called many worse things: “A monument of provocation,” “an insult to freedom of conscience,” “an idolatrous temple built for the glorification of the absurd” (Émile Zola), “a repugnant temple built for a cannibalistic cult.”