1. The historical context: the world Jesus was born into (587 BC–1 AD)

We left the Old Testament in 587 BC, with the Israelites in a parlous state: their king dead, their capital destroyed, their kingdom overrun, and many of their people deported to Babylon: as Psalm 137 (and Bob Marley) has it, ‘By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept … How shall we sing the LORD’S song in a strange land?’ The New Testament picks up the story almost 600 years later and recounts events from about 6 BC to about 100 AD. What was this world? What had changed over the intervening six centuries?

As we have seen, much of the consciousness of the Israelites, and quite probably many of their scriptures, were forged in the crucible of the Babylonian exile. However, that exile was not to last for ever. When Cyrus, King of the Medes and Persians, conquered Babylon 50 years later, he examined the case of the Israelites and very decently decided, not only to repatriate them to their own country, but also to allow them to take with them the confiscated gold and silver of their temple. Though the return was not an easy one (the books of Ezra and Nehemiah, though written a century later, show some of the difficulties), the city of Jerusalem was rebuilt, and a Second Temple was created on the site of the first. This Second Temple, improved and made more splendid over time, gave its name to the whole era between 536 BC and 70 AD.

Much could be said about these 600 years, but the task here is to explain the key events that determined the world, and the consciousness, that Jesus was born into. We can pick out five essentials that would have shaped his awareness: politics, economics, religion, geography, and what we may loosely call ‘messianic expectations’.

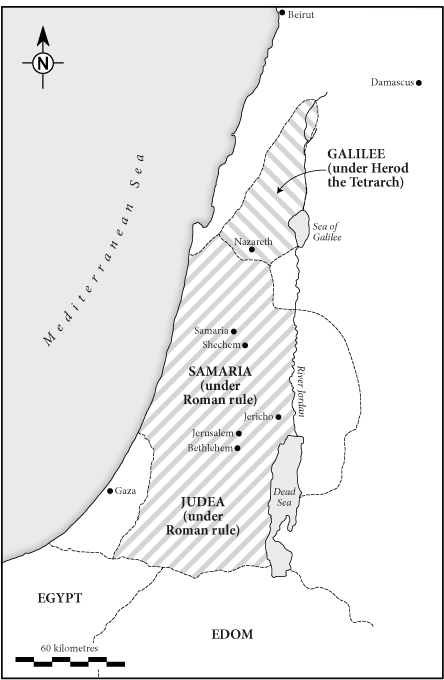

The political context of Jesus’ world was the continuing struggle to liberate the Jews from foreign rule. We have seen that the northern kingdom, the former Israel, had been lost as long ago as 722 BC – indeed it had become by Jesus’ time the much-resented country of Samaria, whose people were condemned as heretics.a

For most of this period, the southern kingdom (formerly Judah, now known as Judea), and its capital Jerusalem, was controlled by outside powers. During this time Jewish culture was profoundly affected by the dominant culture of the Mediterranean at that time, the Greek or ‘Hellenistic’ set of values and practices. But despite this it remained proudly independent in its self-awareness and its political (and religious) ambitions. In 167 BC the Seleucid king (ruler of Alexander the Great’s Eastern Empire) attempted to root out the Jewish religion and install statues of other gods in the Temple. The ensuing rebellion enabled the Jews to throw off foreign control and govern themselves under the Hasmonean dynasty from 140 BC through to 63 BC, when rivalry between different Jewish factions (a recurring theme) enabled Pompey to recapture Judea and bring in Roman rule. From this time on, Judea was a Roman province, though it enjoyed complete religious freedom and was indeed largely ruled by a priestly aristocracy: the now-familiar term ‘theocracy’ was coined at this time by the Jewish historian Josephus to describe the government of Judea. Despite this, the memory of self-government was very strong, and the longing for it dominated both politics and religion.

The economic context is closely related to this theocratic method of government. The Romans always sought to govern through local power structures, and in Judea this meant ruling through the priesthood. The highly centralised structure of Jewish religion meant that wealth and power was concentrated in the Temple, and in the priestly families (headed at the time of Jesus’ ministry by the High Priests Annas and Caiaphas) who ministered in the Temple and owned land all over Judea and Galilee. Herod, governor of Judea (‘King of the Jews’) from 37 BC to 4 BC, was not himself Jewish, but hoped to win the approval of the Jews through a magnificent rebuilding and expansion of the Second Temple. This was accomplished over an extended period, but required a huge amount of money to be raised by taxation, much of it collected from poor peasants working on land owned by members of priestly families. The resulting discontent led to a number of revolutionary movements that we will discuss below.

Third is religion (insofar as this can be separated from politics in a theocracy!). The practice of Judaism in Judea at the time Jesus was born was well established, at least in the urban centres, and securely based on the Torah – obeying the commandments and observing the purity and ritual laws of daily life. All these can be observed in modern Judaism. But within Judaism there were a number of religious groups active in this period, and we should single out four.

Three of them play important parts in the New Testament: Pharisees, scribes, and Sadducees. The Sadducees (tracing their origins to the High Priest Zadok and through him to Aaron, 1 Chronicles 6:4–8) were members of the priestly aristocracy, with largely conservative views. Alongside them we can identify ‘scribes’, likely to be of lower social status but still part of the religious establishment and equally traditional in their obedience to the letter of the Law. The Pharisees, by contrast, were a lay movement concerned to understand the Torah through discussion and debate (we may think of the Bible study groups of our own time). Many were quite senior in the priesthood (Joseph of Arimathea, for example, who gave his family tomb to house the body of Jesus), but Pharisees were closer to the synagogues, places of local worship, than to the Jerusalem Temple, and they were less tightly orthodox than their Sadducee and scribe co-religionists.

The fourth of these religious groups – not mentioned in the New Testament but certainly contemporary with it – were the Essenes, an intense monastic community set up in opposition to the Temple but seeing themselves as faithful to the principles and practice of the Torah. (The Dead Sea Scrolls discovered from 1947 on were the property of the Essene community of Qumran on the shores of the Dead Sea.) They represent one of the strands of the religious life of Jesus’ time and it is quite likely that either he, John the Baptist, or both, would have been aware of their community, which was conservative in religious terms and in its interpretations of the rules of behaviour.

Fourth is geography. We have seen that the old united kingdom of Israel had long gone. In Jesus’ time Samaria (the former northern kingdom of Israel) and Judea were governed by one of Herod’s sons, and Galilee was under the rule of another. All these provinces had very different identities. Judea was the centre of the faith and the heartland of Jewish pride. Samaria had become the home of the hated Samaritans. And Galilee? Galilee had always had a reputation for being rural and remote. It also had a reputation for giving rise to rebellions – Judas the Galilean rebelled in 4 BC and he was not the first. And it was seen as rather comical: Peter is identified by his Galilean accent when he goes to find out where Jesus has been taken (Matthew 26:73), and Geza Vermes in Jesus the Jew (1973) recounts a number of scornful references to Galileans as backward and stupid. The tiny village of Nazareth where Jesus was born and raised was in the heart of Galilee, a fact that clearly did not help his credibility: ‘Can there any good thing come out of Nazareth?’, asks Nathanael in John 1:46. As we shall see, two of the Gospels go to great lengths to arrange for Jesus to be born elsewhere.

Finally there are what we have called ‘messianic expectations’. Since the end of Hasmonean self-rule (140–63 BC), there had been a ferment of revolution in Judea and Galilee9 and a widespread feeling that some kind of saviour – a ‘messiah’ or ‘anointed one’ – was at hand to free the Jews from the yoke of Rome. Exactly what was meant by ‘messiah’ was not always clear. Was it a king who would take on the mantle of David? A liberator who would follow in the footsteps of Moses? A prophet in the mould of Elijah? No one knew, but there was no shortage of brave men – many from Galilee – to lead the movement of national liberation, nor of followers who rallied to their cause. The fact that the Romans hunted down and killed every one was not a deterrent.

That is the world – turbulent, rapidly changing, and intensely political – that Jesus would have been born into somewhere between 6 BC and 4 AD.

Footnote

a. There is to this day a small population in Samaria who still follow their own interpretation of the beliefs, and the Bible, of that period.