6. So – who wrote the New Testament?

We concluded the previous section with what is, or should be, a rather surprising observation: that the testimony of those who knew most about Jesus – his family, his apostles, and his companions – was completely discarded by those who carried his message forward.

We will begin this section with an equally remarkable observation: better known, yet equally regularly overlooked. However little we know about those who wrote the New Testament, we know one thing for sure. It wasn’t Jesus.

This is more noteworthy than it may seem at first glance. If you had a compelling vision of God and man, and a startling insight into the very nature of God – wouldn’t you want to ensure that it outlived you? If you were illiterate (as, for example, Mohammed was), wouldn’t you do as Mohammed did, and find a scribe? And if you could neither write it yourself, nor get it written, wouldn’t you put your mind to bringing together your followers and training them in your knowledge and vision?

It is very obvious – and very striking – that Jesus did none of these things. He chose followers from the Galilean poor: men of character, men of courage, but not men of scholarship. And more striking still, he did not take pains to instruct or coach them in his view of the world. If the Gospels are to be believed, he certainly passed on to some of them his miraculous healing powers even during his lifetime, and we see in Acts that some of his followers were able not only to heal, but even to match his feat of raising from the dead (Acts 20:9–12). But a recurring theme of all four Gospels is the disconnect between Jesus and his followers – his consistent exasperation with their failure to understand him. How patient was he with them? On the evidence of the evangelists, not very.

He is willing to pass on his powers: but with his knowledge he is much more cautious. A recurring theme in the Gospels is Jesus’ repeated injunction, both to his disciples and to those he heals, to ‘Go, and tell no man of this’. This is so emphatic in Mark (1:23–25, 34, 43–44, 3:11–12, 5:40–43, 7:24, 32–36, 8:22–26, 30, 9:9) that a name has been coined for it, ‘the messianic secret’, and a whole literature has (rightly) sprung up around it. We shall return to this secrecy, but whatever the reasons for it, the outcome was to leave the field clear for others to write the story of Jesus. As we have seen, the fall of Jerusalem transformed the faith of the early Christians. And it was these post-Jerusalem believers who wrote the Gospels, Acts, and Revelation. Who were they? And how did the new direction of Christianity influence the story that they told?

We know extraordinarily little about the four evangelists, the people who wrote the first surviving accounts of Jesus. We do not know their names: the original Gospels do not bear an author’s name, and Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John are all merely guesses added 50 years or more after the books were first written and circulated. We do not know where they lived (though it was almost certainly outside Judea). We do not know their sex: it is unlikely that any was a woman, but women do feature largely in all four Gospels, notably in Luke. We do not even know for sure whether the writers were Jews or Gentiles. Matthew anchors his events strongly in the Old Testament, yet it is he who makes the Jewish crowd cry, ‘His blood be upon us’ before the crucifixion; Luke seems to have book-knowledge of the Jewish faith but little practical knowledge of its particular rituals and beliefs (see New Oxford Annotated Bible, p. 1827); and John, who constantly speaks of ‘the Jews’ festivals’, gives the impression that the writer is no more Jewish than his audience.

All this is in marked distinction to the Old Testament, and reflects a deeper contrast. By the 2nd century BC, with the publication of the Septuagint, the Old Testament had taken on a canonical status, which meant that it was forbidden to change a word of it: indeed the later Jewish copiers (the so-called Masoretes) solemnly reproduced the misprints and non sequiturs of the ancient Hebrew texts without feeling able to challenge, let alone correct, what they had inherited.

The New Testament was completely different. All four Gospels circulated in numerous versions from the earliest times and editors and copyists felt no embarrassment about amending the version they had inherited. The texts we now use, initially written between about 70 and 110 AD, were all changed, updated, added to, revised, and rewritten – not to mention copied, with all the errors that introduces – over the next century as theological opinions changed. The result is that we have no certainty as to what was the original version of our modern Gospels: textual criticism, in the old-fashioned sense of establishing an authoritative version, is highly skilled, but also extremely difficult. Any new edition of the New Testament bristles with footnotes indicating the choices that have been made between competing alternatives. As one recent writer reminds us, ‘so much does the interpretation and evaluation of the manuscript evidence progress, that a new New Testament will be issued every ten or twenty years for the foreseeable future’.34

It is obvious that the early copyists had no belief in a ‘sacred’ text in the sense of a hallowed, unalterable ‘vox Dei’. Rather they edited, adapted, and rewrote what they thought of as drafts, to suit their understanding and their purposes. The Masoretic copiers’ sense of a text dictated by God and not to be altered under any circumstances, was in those early days completely absent.

If we know very little about the people who wrote the New Testament, what do we know about the New Testament itself?

Jesus was crucified early in the 30s. The first writings we have – the Epistles largely or wholly attributed to Paul, and possibly the Epistle of James – date from the 40s to the early 60s. (Paul is generally thought to have died in Rome in the mid-60s.) The four Gospels were written somewhere between 70 and about 95 AD: the sequence is Mark, Matthew/Luke, and finally John. They were thus begun almost two generations after Jesus’ death. The remaining thirteen books of the New Testament – Revelation, Acts, and a further eleven Epistles – date from the 80s through to about 110 AD (see Appendix 2).

We have seen that there are significant differences – even major contradictions – between the four Gospels: ways in which they don’t fit with each other, and ways in which they don’t fit with reality. Let us look at each Gospel, and the story it tells, in the light of the historical context and circumstances at the time it was composed, and the pressing problems its author believed the early Church to be facing. Let us ask, for each Gospel: what is the question to which this Gospel is an answer?

The context of Mark’s Gospel (about 70 AD)

The first Gospel in date of composition is Mark, written around 70 AD. What is the context in which Mark wrote? ‘Well before Mark wrote, the mission to Israel had foundered … [the Gospel of Mark’s time] was mostly proclaimed by Gentiles [to Gentiles].’35 The world of Mark’s gospel, the world of the 50s and 60s, was one in which most of the conversions were made outside Israel, and by Gentile preachers rather than by the Jerusalem-based disciples who had travelled with and learned directly from Jesus. Much of the teaching outside Israel was carried out in synagogues – because that was where ‘God-fearers’, Gentiles with an interest in faith, gathered; but the Jews who attended those synagogues were not well disposed to the new religion and many punishments were issued by the synagogue courts to those who preached (Paul writes: ‘Of the Jews five times received I forty stripes save one. Thrice was I beaten with rods, once was I stoned’, 2 Corinthians 11:24–25). Despite this, the Christian establishment of those early years, based in Jerusalem under the leadership of Jesus’ brother James, still saw the teaching of Jesus as aimed at a Jewish audience and fully consistent with the Torah – which meant in turn that they were not sympathetic to efforts to bring in Gentile converts. And in the wider world of Jewry, the level of dispute between Jews and the Roman Empire was steadily increasing.

The key issues that all four Gospel writers had to deal with were the failure of the mission to Jews; the increasing popularity of Christianity among Gentiles; and the delay of the Second Coming. How does Mark tackle these?

Mark’s answer to the first question is straightforward. The Jews rejected Jesus because Jesus had already rejected them. He did not want them to receive the new Gospel. Mark’s Jesus is sharply and consistently critical of the Torah (Mark 7:1–23, 11:27–33). This is bad enough. But Mark’s Gospel claims that Jesus made his message deliberately obscure ‘lest at any time [the Jews] should be converted, and their sins should be forgiven them’, 4:12). The ‘messianic secret’, Jesus’ constant concern to tell no one of his true identity, thus falls into place. Jesus is very selective about who he reveals his true identity to. His status as messiah and Son of God is consistently hidden from Jews until the Passion narrative – or until episodes that refer forward to it. When Jesus asks the disciples who they think he is (8:29), in an episode significantly placed right at the heart of the Gospel, the question feeds directly into a prediction of his coming death and resurrection. (Note also that Jesus neither confirms nor denies the rightness of Peter’s claim that he is the messiah, and strictly forbids the disciples to spread the news any further.)

The same pattern recurs a few verses later, after the Transfiguration: ‘he charged them that they should tell no man what things they had seen, till the Son of man were risen from the dead’ (9:9). Apart from Peter, the only representative of the Jews to identify him as Son of God during his ministry is the high priest (14:61) – and that is during the Passion.

And what of Gentiles? In general they are consistently more receptive to Jesus’ teaching and mission. After the Jews conspire to murder him, multitudes stream out from pagan cities to hear him (3:1–9); after quarrelling over purity laws with Pharisees, he is well received in the non-Jewish region of Tyre (Chapter 7); after the Jews have condemned him to crucifixion, the Roman centurion in charge recognises him as the Son of God (15:39). Indeed the only point at which he breaks his policy of enjoining secrecy after a cure is in the Gentile country of the Gerasenes, where he encounters a man with ‘an unclean spirit’ who identifies him as ‘Son of the most high God’ (5:7): uniquely, Jesus tells this Gentile to ‘Go home to thy friends, and tell them how great things the Lord hath done for thee’ (5:19).

What is happening here? Mark is obviously setting out to validate a mission to Gentiles. But he is doing more. He is projecting back into the time of Jesus the differing responses – Jewish hostile, Gentile receptive – experienced by the Christian missionaries of his own time.36

What about the relationship between the disciples of Jesus in Jerusalem and the preachers of Jesus in the wider world? It is very striking that Mark is not at all complimentary about the disciples. They are always failing to understand, losing their nerve, wrangling among themselves, failing in faith, falling asleep at critical moments. And when it comes to the crucifixion they are presented as utterly craven: the only one who stays with Jesus is Peter, and even he denies him thrice. The only followers who are present at his crucifixion are the women (15:40–41), and it is these women who note where the body is laid, who go with spices to prepare it for burial, and who discover the miracle of his resurrection. Why is this? Why does Mark present the disciples as so weak and fearful? Because he wants to make a contrast. The famous ‘unfinished’ ending of Mark (16:8) is deliberately unfinished. It will be completed in Mark’s own time by the fall of the Temple and the Second Coming. And as Paula Fredriksen puts it, ‘where those who had followed Jesus in his lifetime had failed and fled, those of the first and final Christian generation – Mark’s generation – stood faithfully: enduring till the End, awaiting salvation, keeping watch for the return in glory of the Son of Man’.37

This in turn explains a number of prophecies that Mark places in the mouth of Jesus. The disciples of Mark’s time had to endure violence from many sources – not just beatings from synagogue courts, but attacks from pagans and Romans too. Mark makes Jesus predict this (Chapter 13), consoling the disciples of Jesus’ time for the troubles endured by the missionaries of Mark’s. Jesus suffers and will triumph; if his followers suffer, they will triumph too.

What about the last question that Mark sets out to answer – the time of the Lord’s return? Here is Mark’s special brilliance. The fate of Jesus is matched to the fate of the Temple. Jesus’ crucifixion is apparently a tragedy, but turns as predicted into a triumphant resurrection. The downfall of the Temple – once again an apparent tragedy – signals the Second Coming of Jesus (13:2–8, 14, 29). The clue in the text (‘let him that readeth understand’, 13:14), cannot be a record of what Jesus said. He was speaking, not writing. The intended audience is not the hearer of Jesus’ speech, but the reader of Mark’s writing: one of the elect ‘whom he hath chosen’, and for whom ‘he has shortened the days’ (13:20). It is Mark’s generation, not Jesus’, that will see the return of the Son of Man, and will not pass away ‘till all these things be done’ (13:26 and 30).

The context of the Gospels of Matthew and Luke (85–95 AD) together with Acts (probably 90–100 AD) The next two Gospels to be written – Matthew and Luke, written somewhere round 85–95 AD – seem to have been created entirely independently of each other. But they build directly on Mark, and tell a recognisably similar story. Their work has three components.

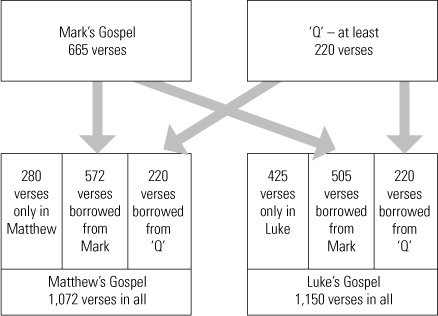

Diagram 7. The so-called two-source theory (© Paul Beeching, 1997, from Awkward Reverence: Reading the New Testament Today (Bloomsbury Continuum), used by permission of Bloomsbury Publishing Inc.).

In part they simply incorporate Mark’s own narrative, though with significant amendments. In part they include a text known as ‘Q’ (from the German Quelle, ‘source’), a collection of sayings of Jesus that has never itself been found but can confidently be known to exist because both Matthew and Luke incorporate it in virtually identical ways into their stories.a

And finally each adds a third component, a very substantial chunk – about a quarter of Matthew and over a third of Luke – of their own devising. It is to Matthew and Luke, not to Mark, that we owe the Nativity stories; the 40-day Temptation in the Wilderness; the Sermon on the Mount; the Lord’s Prayer; and the post-Resurrection appearances. So Matthew and Luke are not only redactors – editors of earlier material – but also authors in their own right.

But why were these Gospels needed? Why wouldn’t Mark do any longer?

The two new evangelists represent the third generation of the followers of Christ. As such their world was very different from Paul’s first-generation world, in which the early followers of Jesus waited expectantly for the return of the leader predicted at the time of the Passion. And it was very different from the world of Mark’s second-generation Christians, for whom the fall of Jerusalem had become the signal of the approaching return, and who as a result could once again watch and wait for the Second Coming with lively hope. By the 80s and 90s that hope had faded. It had become clear that those groups that had seemed merely means to an end, places to wait for the coming of the next world, were in fact ends in themselves, communities whose purpose was to live a Christian life in this world and pass on that tradition to their descendants. But how were they to live? What tradition did they themselves inherit, and what would they in turn pass on to their descendants?

Mark, the Gentile writing for Gentiles, could offer no guidance here. Nor could he offer guidance on how to deal with the Jewish element of the faith – its Jewish converts, its Jewish roots, and its need not only to co-exist, but also to define itself against and in competition with the Jewish communities of the Diaspora who still played such a major part in the process of winning new recruits.

What is more, the world in which these third-generation Christians lived had changed radically. Mark’s generation had grown up in the shadow of Jerusalem, both as Jewish Temple and as ‘mother church’ of the Diaspora Christians. Now the Second Temple was gone and with it Jewish Christianity. In its place came a need to honour the founders of Christianity – the Jewish disciples who had been called by Christ himself to follow him.

Finally, the expansion of Christianity had brought with it an expansion of sects and a diversity of teaching. Mark, focused on the imminent Second Coming, had very little to say about this. Now it was time to speak out for the true faith against the false prophets who claimed to speak for it.

We have seen how Mark deals with the three great issues that faced the early Church – the failure of the mission to the Jews, the growing success of the faith among the Gentiles, and the delay of the Second Coming. Matthew and Luke answer these questions in different ways.

Matthew’s gospel, in vigorous contrast to Mark’s, is the work of a Jew writing for Jews – former Jews who had converted, and practising Jews who had not yet done so. And where Mark’s Jesus had deliberately hidden his message, and his true divine nature, from the Jews, Matthew’s Jesus aims his message directly at them: ‘I am not sent but unto the lost sheep of the house of Israel’ (15:24 – this passage is unique to Matthew). This new approach requires Matthew both to rework Mark’s text, and to add to it.

Where Mark’s Jesus enters the story fully adult, Matthew begins with a birth narrative. It starts 42 generations before birth, providing a genealogy for Jesus that places him squarely in the tradition of Hebrew sacred kingship, starting with Abraham and going via David, the ‘once and future king’ of Jewish mythology and apocalyptic tradition. Matthew gives Jesus a miraculous birth to a virgin mother, foretold by Isaiah and announced by an angel; he locates his birth in Bethlehem, the birthplace of David; he has Wise Men coming from the East to kneel and pay homage to the child, showing the submission of Gentiles to Jews; and he follows the birth with a ‘descent into Egypt’ to escape from Herod, thereby connecting Jesus to another Old Testament hero, in this case also with miraculous origins, Moses.

In Mark, Jesus appears to be rejected even by his own family (‘A prophet is not without honour, save in his own country, and among his own kin, and in his own house’, Mark 3:21, italics added). In Matthew the episode is softened by taking out the passage in italics; Luke (4:24), as we shall see, takes out ‘in his own house’ as well, thus further weakening any criticism of Jesus’ Jewish heritage. Where Mark’s twelve apostles are sent out without any limitations (Mark 6:7ff), Matthew’s are told firmly to avoid Gentile and Samaritan cities in favour of ‘the lost sheep of the house of Israel’ (Matthew 10:5–6). And where Mark’s Jesus heals the Gerasene demoniac and tells him to proclaim his message to the Gentiles (Mark 5:19), Matthew’s version of the story ends with the Gentiles begging him to leave (Matthew 8:34).

Moreover Matthew’s Jesus, unlike Mark’s, openly reveres the Torah: ‘I am come not to destroy, but to fulfil. For verily I say unto you, Till heaven and earth pass, one jot or tittle shall in no wise pass from the law, till all be fulfilled’ (Matthew 5:17–18). And Matthew is a massive user of ‘prooftexts’, passages from the Old Testament used to emphasise Jesus’ Jewish roots and to show that his coming fulfils Jewish prophecies from the earliest days: quotations from Micah and Samuel, Jeremiah and Isaiah, are stitched through Matthew’s text (see for example 1:22–23; 2:15, 17–18, 23; 4:14–16; 8:17; 12:17–21; 13:35; 21:4–5; 27:9–10), binding the New and the Old Testaments – the Christian and the Hebrew Bibles – into a single unit.

Nor is this all. Matthew places his extracts from Q in five blocks, starting with the Sermon on the Mount, in a way that seems to mirror the five books of the Torah. And the way in which they are presented – ‘ye have heard that it was said by them of olden times … but I say unto you’ – would be instantly recognisable to a Jew of Matthew’s time both as a literary style and as a method of preaching.

What of the disciples? Those passages in which Mark emphasises their dullness, stupidity, and (at the crucifixion) absence, Matthew rewrites. Where Mark’s Jesus rebukes the disciples for their lack of understanding (Mark 4:13), Matthew celebrates their good fortune and privileged status (Matthew 13:16–17). Where James and John ask for a special place in the coming Kingdom of God, Matthew attributes the request to their mother (Mark 10:35–45, Matthew 20:20–28; Jewish-mother jokes have a long ancestry …).

When Jesus asks the disciples who they think he is, he criticises Peter harshly both in Matthew and in Mark (Matthew 17:22–23, Mark 8:32–33), but only in Matthew does he also bless him and appoint him head of the new Church (16:17–19). And at the end of the book – a point we will return to – it is the disciples who first receive the new mission, one that includes not only Jews but also Gentiles: ‘Go ye therefore, and teach all nations’ (Matthew 28:19).

What of diversity of faith? Matthew alone among the four Gospel writers uses the word ‘ekklesia’, meaning a continuing community of believers united around a single system of belief. He is very insistent on judgement, most famously in the great story of the Last Judgement: ‘And before him shall be gathered all nations; and he shall separate them one from another, as a shepherd divideth his sheep from the goats’ (25:32). (Curiously the only criterion for salvation here is love, and not even love of God – it is love of one’s fellow man!)

However, elsewhere Matthew’s pronouncements are much less inclusive. He warns against heresies (‘Beware of false prophets’, 7:15) and has a parable that appears nowhere else, the Parable of the Tares (13:24–30), with a gloss (13:37–43) explaining how – in another Last Judgement – the Lord will return to assess not only those outside the Church, but those within it. Even Matthew’s positive comments on the first disciples after the Resurrection are tempered by a carefully worded hint that even then not all was well (‘some doubted’, 28:17), suggesting that the different church traditions that so troubled Matthew in his generation had sprung from false transmission of the faith in the earliest days.

Finally there is the difficult question: who is the message of Jesus aimed at? Matthew’s Jesus is a Jew preaching to Jews – and yet he closes his Gospel with the magnificent injunction to take the good news to all nations. How does Matthew achieve this transformation? How can Jesus both be sent to the Jews, and sent to the Gentiles? And how can Matthew come, in a book aimed at a Jewish audience, to be the most savage of the evangelists in his condemnation of the Jews’ part in Jesus’ death?

Matthew’s answer is to place Jesus in a long tradition of Jewish prophets – but to explain that the Jews always reject their prophets. When Jesus comes to Jerusalem before the Passion, a huge shift takes place in the way he speaks about the Jews. Chapters 21–23 are full of stories about the failure of the Jews to accept the warnings their prophets bring them: the cursing of the fig tree (21:19), the two tales of the vineyard (21:28 and 33), the tale of the wedding banquet (22:2–14), the judgement that ‘the kingdom of God shall be taken from you [i.e. the Jews], and given to a nation bringing forth the fruits thereof [i.e. the Gentiles]’ (21:43). The rejection of the prophets is itemised in Chapter 23: ‘O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, thou that killest the prophets, and stonest them which are sent unto thee’ (23:37). And it is reinforced a few verses earlier with a comment strictly from the experience of Christian missionaries of the 90s rather than Jesus’ world of the 30s: ‘Wherefore, behold, I send unto you prophets, and wise men, and scribes … and some of them shall ye scourge in your synagogues, and persecute them from city to city’ (23:34).

So Matthew draws a distinction between ‘good Jews’ (the prophets, the holy family, the disciples, Jesus himself) and ‘bad Jews’ – scribes, Pharisees, and the mob who reject Jesus at the Passion. Mark had explained parables as a way of deliberately hiding the truth from outsiders ‘lest at any time they should be converted, and their sins should be forgiven them’ (Mark 4:12, emphasis added), putting the responsibility with God. Matthew, in a careful rewording, explains that the fault lies with the hearers themselves: ‘And in them is fulfilled the prophecy of Esaias [Isaiah], which saith, By hearing ye shall hear, and shall not understand: and seeing ye shall see, and shall not perceive’ (Matthew 13:14). In Matthew’s account, the Jews were offered salvation, but rejected it. As they always did, they have brought destruction on themselves.

By the end of Matthew’s Gospel, the Jews have comprehensively thrown away the chance of salvation for which their whole history was preparing them, offered to them by a Jewish saviour foretold throughout Jewish scripture. Matthew highlights the innocence of Pilate – warned by his wife in a dream, compelled by the Jewish mob, and finally washing his hands of the blood – and the guilt – of the Jews: ‘His blood be on us, and on our children’ (Matthew 27:25). And the way is clear for Jesus to send his followers out ‘to teach all nations’ (Matthew 28:18–19).

We have seen how Mark and Matthew dealt with the great issues that faced the early Church. What is Luke’s approach?

Before we answer this, there are some points we need to clarify. The first is that Luke actually wrote not one, but two of the books of the New Testament – not only Luke’s Gospel, but also the Acts of the Apostles. Although Luke’s Gospel is likely to be contemporary with Matthew (85–95 AD), the Acts may be as late as 100 or even later. We don’t know, and it isn’t critical that we should. Most scholars now refer to Luke–Acts as a single entity; for our purposes here I will take them one after the other to follow the careful development of Luke’s arguments over the two books.

‘Careful’ is a good word for Luke. Here is the opening of his Gospel:

‘Forasmuch as many have taken in hand to set forth in order a declaration of those things which are most surely believed among us, Even as they delivered them unto us, which from the beginning were eyewitnesses, and ministers of the word; It seemed good to me also, having had perfect understanding of all things from the very first, to write unto thee in order, most excellent Theophilus, That thou mightest know the certainty of those things, wherein thou hast been instructed.’ (Luke 1:1–4)

This prologue – modelled on the standard introduction to Greek histories of the time – defines his values: measured, thorough, judicious, recognising the great distance that separates him from the events he is writing about, but confident that truth can be sifted from rumour. We think of the 2010 Saville Inquiry into the events of Bloody Sunday: twelve years in the making and 38 years after the event itself, but authoritative enough, when it finally appeared, to cause a Prime Minister to apologise to Parliament. Theophilus, incidentally, may be a real person or a symbol (it means ‘lover of God’ in Greek), but if it is a real person, the designation ‘most excellent’ indicates that it is someone of high status (perhaps like the person who commissioned the Saville Inquiry).

Luke’s character shines through both books. His language is both beautiful and flexible, varying in character from the pure Greek of this prologue, through the more archaic Septuagint Greek of his Nativity story (probably following the style of its unknown source), and on to the unpolished koine Greek of Acts. His view of history is always a kind and inclusive one, supporting the underdog, bridging over conflicts, looking to overcome contradictions, and trying to be fair to both sides of every argument. In his Gospel, this comes through most clearly in the way it is structured, and before we answer the three questions above, we must briefly explain how his Gospel is put together.

As we have seen, Matthew and Luke both build on Mark, and both include material from Q, the mysterious and missing sayings of Jesus. But both evangelists also add much material of their own. Matthew’s own contribution comes to fractionally over a quarter of the Gospel that bears his name: 280 of his 1,072 verses are neither Q nor Mark. Luke’s Gospel is of very similar length (1,150 verses); but 425 of these, or over a third, are from Luke himself. These contributions are very revealing. Where would we be without the parable of the Good Samaritan? Or the Return of the Prodigal Son? How can we forget Dives and Lazarus, or Mary and Martha? And what about the story of the Pharisee and the tax collector?

‘Two men went up into the temple to pray: the one a Pharisee, and the other a publican [tax collector]. The Pharisee stood and prayed thus with himself, God, I thank thee, that I am not as other men are, extortioners, unjust, adulterers, or even as this publican. I fast twice in the week, I give tithes of all that I possess. And the publican, standing afar off, would not lift up so much as his eyes unto heaven, but smote upon his breast, saying, God be merciful to me a sinner. I tell you, this man went down to his house justified rather than the other.’ (Luke 18:10–14)

The most striking aspect of Luke’s own contributions to the Gospel story is his concern for women. This starts with the infancy narrative – of which more below – and goes on throughout the book: the raising of the widow’s son at Nain (7:11–17), the woman who bathes Jesus’ feet with tears (7:36–50), the women who accompany and help to fund Jesus and the disciples (8:2–3), the healing of a crippled woman on the Sabbath (13:11–13), the lamentation for the daughters of Jerusalem (23:28–31). All the Synoptics credit the women with finding the empty tomb; but only Luke points out their forethought in getting the spices they needed for the burial before the shops shut (24:1)!

So – how does this gentle, courteous, urbane Greek-speaker deal with the three burning questions?

In his Gospel, Luke’s position is very different from that of his Synoptic colleagues. Luke sees Jesus as eagerly awaited by the people of Israel, who widely welcomed him and were largely willing to accept the new faith. Consequently he denies that the mission to Jews has failed.

Luke’s Saviour is universal and inclusive. By creating a genealogy that goes back, not as in Matthew to Abraham, the founder of the Hebrews, but to Adam, the founder of humanity, he includes all the branches of the human race (Luke 3:38). By sending the Angel Gabriel to Mary, and by giving her the great hymn we know as the Magnificat, he emphasises the importance of women (Chapter 1). By placing the birth of Jesus in a stable and announcing him first to shepherds, he includes all classes of society (2:7–16). And Jesus’ Jewish identity is proudly affirmed by his birth in Bethlehem, by his circumcision, by his presentation at the Temple, and by Simeon and Anna, devout Jews, who see the baby and recognise him as ‘the Lord’s Christ … A light to lighten the Gentiles, and the glory of thy people Israel’ (2: 26, 32). (Anna even speaks of ‘redemption in Jerusalem’, 2:38.)

Luke is at pains to rehabilitate the (Jewish) disciples that Mark had so severely criticised. Rewriting the account he inherited from Mark, he praises them as ‘they which have continued with me in my temptations’; he promises that they will ‘sit on thrones judging the twelve tribes of Israel’; and when Jesus finds them sleeping in the garden of Gethsemane the night before his crucifixion, Luke explains that it is ‘for sorrow’ (22:28, 30, and 45). Where Mark and Matthew have two bandits crucified alongside Jesus who (like the passers-by) taunt and revile him, Luke has one of the bandits ask for, and receive, mercy: ‘To day [sic] shalt thou be with me in paradise’ (23:43). Where Matthew’s Jesus was in the outsider tradition of the prophets, Luke’s Jesus is a fully paid up, mainstream Jew, supported by the whole sweep of Jewish history and the full weight of the Torah (24:25–27, 44–47).

As Paula Fredriksen puts it, ‘Luke’s Jesus is a traditionally pious Jew (e.g. 4:16), who even as a child engaged Jewish teachers in dialogue and awed them with his understanding (2:46)’.38 He even has supporters among the Pharisees: although annoyed by his violations of the Sabbath (6:11, 13:10–17, 14:1–6), they try to persuade him to flee when he is endangered by Herod Antipas (13:31–33). Who does oppose and harass him? The chief priests and scribes (19:47 and 20:19– 26; note that Luke omits any mention of the Pharisees in these episodes). The Roman centurion whose slave Jesus heals appears also in Mark, but Luke characteristically adapts Mark to tell us that the Gentile centurion is also aligned with the Jews: ‘For he loveth our nation, and he hath built us a synagogue’ (Luke 7:5).

Luke’s treatment of the Temple is particularly revealing. The Cleansing of the Temple that is so important in Mark and Matthew is allocated only two verses in Luke (19:45–46), and he omits Mark’s and Matthew’s prophecies of the destruction of the Temple at Jesus’ trial and crucifixion. What is more, after the crucifixion the apostles honour the Sabbath, resting ‘according to the commandment’ (23:56); the good news of Jesus is to be proclaimed to all nations, but ‘beginning at Jerusalem’ (24:47); and the Gospel ends with the apostles continually praising God – where else? – ‘in the temple’ (24:53).

Mark has the Jews calling for the death of Jesus: Matthew even has them explicitly accepting responsibility for that death. How does Luke treat this? He clearly cannot avoid implicating the Jews in the crucifixion because like his fellow Synoptics, he has to find a way to exculpate the Romans. Accordingly he has Jesus judged by the Sanhedrin and brought by them before Pilate. But his treatment of the events is very different from both Mark and Matthew. Around this rejection by the people, he wraps their adulation in the run-up to the Passion (Luke 19:48, 20:26, 21:38) and their grief and sorrow on the very day of the crucifixion: by contrast with the taunting abuse of Mark and Matthew’s watchers, Luke’s Jesus is followed by grieving women; gives up his life with the tranquil, ‘Father, into thy hands I commend my spirit’ (23:46) rather than Mark’s anguished ‘My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?’ (Mark 15:34); and is mourned by repentant crowds (Luke 23:27 and 48). Only in Luke do we find the famous saying from the cross, ‘Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do’ (23:34).

So Luke in his Gospel answers the first two questions very similarly: the mission has succeeded, or at least had a considerable impact, both with Jews and with non-Jews. What of the third question, the delay in the Second Coming?

It seems that Luke could not avoid citing some of the familiar warning passages, most notably in Chapter 21, which echoes fairly closely Mark 13 and Matthew 24. In particular, rather puzzlingly, he exactly follows both Mark and Matthew in the famous verse in which Jesus promises that he will return in the lifetime of his hearers (‘Verily I say unto you, This generation shall not pass away, till all be fulfilled’ – Luke 21:32; compare Mark 13:30 and Matthew 24:34 for an identical message). And he also suggests that the fall of Jerusalem – a matter of history by the time Luke wrote – will be a sign of the Second Coming (Luke 21:20–28). This is strange for two reasons: first, and obviously, because by the time of Matthew and Luke it clearly had not happened; and second, because it does not correspond to the emphasis elsewhere in Luke, and in Acts, on the idea that what matters is not the Second Coming, but the first – Jesus’ message and his resurrection – and its consequences for the community of believers. Perhaps he simply had to put in this material because it was so well known. We shall never know!

But for the most part Luke avoids the whole idea of a delay in the Second Coming. First, he unobtrusively lengthens the timescale. Mark promises that the Lord ‘hath shortened the days [until the Second Coming]’ (Mark 13:20). Matthew, in a verse that otherwise follows Mark almost word for word, subtly varies the timing, promising only that those days ‘shall be shortened’ (Matthew 24:22). Luke omits the phrase entirely. Where Mark’s Jesus tells the high priest that he ‘shall see the Son of Man sitting on the right hand of power, and coming in the clouds of heaven’ (Mark 14:62), Luke’s Jesus promises only that the Son of Man ‘shall sit on the right hand of the power of God’ (Luke 22:69). But most importantly, he gets over the idea of a delay by asserting that the Kingdom has arrived already. Where Mark’s ‘Kingdom’ will come only when Jesus returns in power, Luke’s ‘Kingdom of God’ is present with the earthly Jesus and the faith of his followers: ‘The kingdom of God cometh not with observation … for behold, the kingdom of God is within you’ (Luke 17:20–21; see also 8:1, 9:2, 10:9).

This leaves us with only one question to resolve – but it is a sticky one. The Luke of the Gospel may assert that the Jews have been receptive to the message of Jesus; but the Luke of Acts knows that by the time at which he wrote, they had by and large rejected it. If the Gospel does not explain the failure of the mission to the Jews, how does Acts explain it?

Acts has been well described as having two parts: the Acts of Peter (the first half), and the Acts of Paul. The initial mission from the risen Jesus commands the apostles to bear witness ‘in Jerusalem, and in all Judea, and in Samaria, and unto the uttermost part of the earth’ (Acts 1:8). Very soon this becomes a reality with the experience of speaking in tongues at the feast of Pentecost: the 120 believers in Jerusalem find themselves speaking diverse languagesb to ‘Jews, devout men, out of every nation under heaven’ (2:5, 9–11), and Peter makes a splendid speech acknowledging the part played by the Jews in the death of Jesus, but explaining that this death was ‘by the determinate counsel and foreknowledge of God’ (2:23) and offering to his Jewish audience the opportunity to repent and be baptised (2:38). (Characteristically, Luke shows them as ‘pricked in their heart’ – Acts 2:37.) So successful is this appeal that 3,000 new recruits add themselves to the faith (2:41). This process is repeated soon afterwards, again with the emphasis that the Jews and their rulers acted in ignorance (3:17), with even greater success in the form of a further 5,000 souls (4:4).

The first Jewish resistance comes from the high priest and the Sadducees, ‘filled with indignation’ (5:17–18) and probably less than enthusiastic about the constant reminders of their part in Jesus’ death. But despite prison and flogging the apostles continue to teach and preach ‘daily in the temple’ (5:42), to the point where ‘a great company of the priests were obedient to the faith’ (6:7).

What seems to be a decisive break occurs when Stephen reproaches the high priest and members of the Temple Council for their habit of killing prophets. Not surprisingly, the council members are enraged at this and stone Stephen to death (with the assistance of Saul, soon to be Paul). This leads to a severe persecution in Jerusalem, but the faith continues to spread: the surviving apostles just move on to Judea and Samaria and thence to Caesarea (Acts 8), Lydda, and Joppa (modern Jaffa). By Chapter 9 the word has got out as far as Phoenicia, Cyprus and Antioch (11:19), and the believers from these Diaspora cities are even persuaded to get together a collection for famine relief back home in Judea (11:27–30).

From Acts 13 the focus shifts from Peter (increasingly concerned with Israel) to Paul: ‘the Holy Ghost said, Separate me Barnabas and Saul for the work whereunto I have called them’ (13:2). And this is where the real trouble starts. In each new Gentile city they visit, Paul and Barnabas do the obvious thing: they go to the synagogue to preach. Why? For a variety of reasons. First, because as practising Jews it is their natural home, the obvious place to ‘check in’. Second, because they want to spread the word to the Jewish congregation who worship there. But there is a third reason that is more double-edged. Synagogues, as we have seen, attracted ‘God-fearers’, pious Gentiles drawn to the Jewish faith and practice by its ethical teaching, its historical depth, its developed religious practice, and its support of its own poor and needy. So how is it going to be if a different branch of Judaism – the Christian branch – suddenly breezes into the synagogue and starts trying to win over not only the Jews, but also the God-fearers? A branch that blames the Jews (not the God-fearers) for killing its Saviour, and insists on Jewish repentance as a precondition for conversion?

There was yet another reason for Diaspora Jews to be very wary of the Christian missionaries. The message of the early Christians, as we have seen, focused powerfully on the approaching ‘end days’ – the Second Coming of Jesus. The natural consequence of this was to abandon the ordinary practices of life in order to dedicate oneself to preparation for the life to come. We know from various of Paul’s letters (notably 2 Thessalonians 3) that this was an unintended consequence of early Christian preaching. But such behaviour was not just a nuisance. It could also be a danger. Anti-Jewish riots were not unknown: Tiberius expelled the Jews from Rome in 18 AD and Claudius did likewise around 49 (as Luke mentions in Acts 18:2); and there had been a pogrom in Alexandria in 38. Stirring up discontent would be seen by the elders of the synagogue as highly provocative to the local community. (We remember the decision of the high priest to hand over Jesus to prevent riots at the Passover in Jerusalem.) In such circumstances, God-fearers were not just potential converts; equally importantly, they were friends, allies, and supporters in a world in which the Jewish community were immigrants – ‘strangers in a strange land’ – and in a small and defenceless minority.

So the early missionaries were in something of a bind. The synagogue was the obvious place for them to go, and the most fertile ground for them to plough; and yet it was also where they represented the greatest threat. And in Luke’s account, this is indeed where the relationship between the Jews and the early Christians turns sour. Time after time – Antioch, Iconium, Lystra, Thessalonica, Beroea, Corinth, Achaia – Paul and his fellow missionaries repeat the same pattern: a warm welcome and an invitation to speak when they call in at the local synagogue, a lively response to their talk from Jews and non-Jews alike, and then, a week later, a bitter resistance from the local (or neighbouring) synagogue authorities.

The pattern of strife with the Temple authorities is repeated, for different reasons, when Paul returns to Jerusalem (Acts 21:27–32), but finally Paul sets sail for Rome, and there he finds the same mixed reception (28:24). And only then does Acts finally and definitively answer the question posed in Luke’s Gospel: how do we account for the non-success of the mission to Jews?

‘Well spake the Holy Ghost by Esaias the prophet unto our fathers, Saying, Go unto this people, and say, Hearing ye shall hear, and shall not understand; and seeing ye shall see, and not perceive … Be it known therefore unto you, that the salvation of God is sent unto the Gentiles, and that they will hear it.’ (Acts 28:25–28)

The villains of the piece are the Jews of the Diaspora. The crime of killing Jesus could be and had been forgiven; the crime of turning away his message, could not.

The Gospel according to John (probably two stages, c. 70 AD and c. 95 AD)

Who is this who comes in splendour, coming from the blazing East?

This is he we had not thought of, this is he the airy Christ

(Stevie Smith, ‘The Airy Christ’)c

The last of the four Gospels is ‘According to John’ (though there is no certainty as to who this John was). What kind of work is it? Well, as the quotation above implies, the reader should prepare for a shock. Paula Fredriksen points out that ‘John’s Jesus is not the wandering charismatic Galilean who appears [in Matthew, Mark, and Luke], but an enigmatic visitor from the cosmos above’.39 This Jesus does not talk in the rough, agricultural language of his farming background. He speaks a language of light and darkness, of above and below, of Water and Spirit, of the Bread of Life, of the Vine and the Branches: he uses the Temple as a metaphor for his body, and the cross as a metaphor for being lifted up to heaven, and constantly speaks in riddles. The witty, earthy, cheeky boy of Mark’s Gospel could not be further away: this is an aloof, solitary, passionate dreamer from another planet, who, like the hero of Isherwood’s 1962 novel, is only ‘down here on a visit’.

Indeed John’s Gospel is so different that right up until the 4th century the Church hesitated as to whether to include it in the canon: some Church fathers, known as the alogoi (‘those who reject John’s logos theology’), refused to accept it at all.

How did John’s Gospel come into being? For many years it was thought to be very late indeed – perhaps as late as 150–200 AD – because of the very distinctive ‘Gnostic’ quality of its thought (see below). But we now know that Gnosticism was active much earlier; material from John’s Gospel has been found dating to about 130, and most current scholars think it was composed in two stages, the earlier around 70 AD, the later around 95.40

One consequence of this two-stage and perhaps two-author theory is that it helps to explain some of the extraordinary muddles in the text. Chapters 5 and 6 are out of order: in Chapter 5 Jesus leaves Galilee, and in Chapter 6 he is back in Galilee. This difficulty is easily fixed by reversing the order of the two chapters. But in 7:21 Jesus says he has performed only one miracle: the text says he has performed at least four. In the very next verse Jesus states that Moses ordered circumcision, whereupon the editor rather brusquely corrects him (7:22). In 12:36 Jesus ‘departed and did hide himself from them’, but by 12:44 without any warning he is back preaching again. In 13:36 Peter asks him where he is going: in 16:5 Jesus complains that no one asks him where he is going … and so on.

Overall, John leaves out a great number of what we have come to consider essential elements of the Christian narrative. The broad outlines of the story are recognisable: John’s Jesus meets the Baptist, preaches, performs miracles, goes to Jerusalem, is crucified, and rises again. But the similarity hides profound differences. John leaves out many of the elements that emphasise the physical nature of Jesus: no birth story, no actual Baptism, no Temptation, no Sermon on the Mount, no parables, no Eucharist at the Last Supper. Conversely he puts a lot in, notably miracles such as the Raising of Lazarus and stories such as Doubting Thomas, and – perhaps most famously – the Woman Caught in Adultery (John 8:1–11). The timescale for the preaching of Jesus is different, with three years allowed for it, and multiple visits to Jerusalem, rather than the single packed year of the Synoptics. And even more than Luke, John writes in a highly formal style using a range of complex structures drawn from Greek rhetoric.

We know the historical context of this period because it is the same as Luke, and to some extent as Matthew: the rise of rabbinical Judaism, the ‘Diaspora Wars’ that arose as an increasingly Gentile faith tried to win converts through the network of Jewish synagogues, and a growing bitterness between different branches of the new faith. To this we can add an increasing climate of Gnosticism, an attitude to the world with deep roots in Persian mysticism but which flourished in Hellenist, and in parts of Jewish, mysticism in the early centuries of the Christian era. In Gnosticism, flesh and the world of matter are inherently fallen and evil. Salvation is through Spirit: it comes to those ‘Which were born, not of blood, nor of the will of the flesh, nor of the will of man, but of God’ (John 1:13). John wrote in the Gnostic tradition. Against this context, how does John answer the three questions that so troubled the early Church: the lack of success among the Jews, the relative success among the Gentiles, and the delay of the Second Coming?

Unlike Luke, John agrees that the Jews have rejected Jesus. Writing rather later than Mark, he has more evidence to go on: by the 80s there is evidence that Jewish Christians, and perhaps Gentile Christians too, were not welcome in synagogues, and John (anachronistically) makes Jesus refer to this in 9:22 and 16:2. His explanation for this is the same as Mark’s, quoting Isaiah 6:10 to show that in fact Israel did not reject the mission: it was never really offered to them. The Lord has ‘blinded their eyes, and hardened their heart’ (John 12:40; see also 5:44–47, 8:19 and 47, and 10:26–27). His references to the Jews are off-hand, distant, dismissive: ‘the Jews’ Passover was at hand’, 2:13, ‘as the manner of the Jews is to bury’, 19:40. With a final flourish, John makes the Chief Priests (of all people) say that ‘We have no king but Caesar’ (19:15)! And like Mark, John is not concerned about this because his Jesus comes not to the many, but to the few: ‘He came unto his own, and his own received him not. But as many as received him … to them gave he power to become the sons of God’ (John 1:11–12; see also 6:44–51, 8:19, and passim).

So John’s Jesus includes Samaritans (Chapter 4) and Gentiles in his preaching: ‘Other sheep I have, which are not of this fold: them also I must bring, and they shall hear my voice’ (10:16). But he knows that the flock will not be a big one.

What of the delay of the Second Coming? Here we come to the nub of the question. In John’s Gospel, Jesus is not of this world – and nor is his kingdom (18:36; see also 5:24, 15:19, 16:33). John’s Gnostic roots enable him to sidestep the requirement for a crusading messiah to return in glory and transform the world. John has ‘a high Christology’ – he is absolutely emphatic that Jesus is the Son of God, rather than just another prophet, and that at his death Jesus will return to his place at the right hand of God. But John has no expectation that Jesus will return to earth to fight the messianic fight and liberate Judea. His kingdom is not of this world. So when will he come again? There is no need to come again. There has been no delay. His kingdom has already arrived. ‘Be of good cheer: I have overcome the world’ (16:33). Where Mark’s Jesus wrestles with fear, pain, and despair at his crucifixion, John’s progresses serenely to the cross as to a coronation, and dies with tranquillity: ‘It is finished’ (19:30). The horizontal axis of Mark – from present awaiting, to future return – has in a sense gone vertical: the only movement is a timeless one, from below to above.

This solves three major problems for the new faith. First, it avoids the difficult question – hard enough for believing Christians, and exceptionally difficult for Christian missionaries trying to clarify the faith to non-believers – of when to expect the return of the Lord. Second, it differentiates the new faith from Judean messianic expectations – and in doing so, defines another way in which Christianity has moved on from its Jewish roots. And finally, perhaps most importantly, it explains to any potential Roman critics that Christians are not dissidents, revolutionaries, millenarians, terrorists. ‘My kingdom is not of this world …’.

So John has performed a major feat: one of enormous importance to the current and future fortunes of Christianity. He has made Jesus safe. Salvation has moved from this world to another one; from outer action to inner state; from Marx to Maharishi.

Is this enough about John? Not quite. Curiously, John’s Gospel – so remote, so other-worldly, so unconcerned with practical details – seems actually more reliable than the Synoptics in the few concrete details that it does give. Where the Synoptics allow Jesus only a year’s ministry and a single visit to Jerusalem, John allows him three or four, and tells us that during the first year Jesus was almost arrested (7:32), as he was on his final visit (11:57). The Cleansing of the Temple occurs much earlier (John 2:13–16) and cannot therefore be the trigger for the arrest. The way Jesus is treated by the Temple authorities on his sequence of Passover visits to Jerusalem fits well with the theory advanced by Elias Bickerman,41 according to which Jesus was outlawed by the Roman authorities, with a price on his head, on the first visit and therefore remained in hiding – or in such a public place that the crowds would protect him – on his subsequent Passover visits. When Judas betrays him, he knows the place that Jesus regularly hides (John 18:2); the squad sent to arrest him consists of both Jewish police and Roman soldiers, as befits an outlaw. As a known outlaw he is bound at once (18:12); and for the same reason, no trial before the Sanhedrin is required. Jesus has form and can be passed straight to the governor for sentence.

There are several other places in which John’s account is persuasive. As we have seen, the timing of the Last Supper is a problem in the accounts of the Synoptics: John solves the difficulty, placing it a day earlier, on the Thursday, the night before the Passover Festival (13:1). And John’s report of the Resurrection (20:1–18) is extraordinarily spare and concrete when set against the rather overwrought accounts in Matthew, Mark, and Luke. Curiously, John the story-teller speaks very differently from John the Gnostic theologian, and we cannot but be reminded of the moments when the writer, speaking as ‘the disciple whom Jesus loved’, claims to have personally witnessed the events he writes of (13:23–26, 19:35, 21:7, 21:24) – a claim not made in similar fashion by any of the Synoptics.

And there is still more to say about John. Much of his Gnosticism has not worn well: the teaching is often repetitive and wearisome and one is not surprised to hear that at one point ‘many of his disciples went back, and walked no more with him’ (6:66). But for all its oddities, John’s Gospel still gives us some of the most memorable, magnificent, and consoling passages of the whole Bible. The mysterious, awe-inspiring opening of the Gospel, with its deliberate echoes of Genesis (‘In the beginning was the Word’); the softness and embracing warmth of his care for his disciples (‘For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life … I am the good shepherd: the good shepherd giveth his life for his sheep … In the world ye shall have tribulation: but be of good cheer; I have overcome the world’, 3:16, 10:11–12, 16:33); the inclusive power of ‘I came not to judge the world, but to save the world’ (12:47); and the breathtaking, ‘Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends’d (15:13). We remember that John alone has the wonderful verse, ‘Jesus wept’ (11:35).

Perhaps the best place to leave John is where we began, with Stevie Smith:

… he does not wish that men should love him more than anything

Because he died: he only wishes they would hear him sing

(Stevie Smith, ‘The Airy Christ’)

How was the New Testament put together?

Before turning to Jesus himself as he is presented in the Bible, we need to round off this part of our account by briefly examining how we come to have the canon of 27 books that form the New Testament as we have it now. (‘Canon’, from the Greek word for yardstick, was used by literary critics in the ancient world to define the body of literary texts they thought worthy of study.)

As we have seen, the scattered ‘house churches’ of the 1st century AD, each with its own doctrine and practice, rapidly felt the need for a consistent body of teaching. By about 150 AD a single body of texts, including the four Gospels, was accepted as ‘canonical’ throughout the expanding Christian world. (The differences between the four Gospels were well known even then, and a document that edited and spliced them into one, the Diatessaron, was written by Tatian around 160 AD and widely used.) We have seen that the Torah, the powerhouse of the Old Testament, was edited and recast by one man, the scribe Ezra. Is there a similar process at work with the New Testament?

From one point of view, the answer is a definite no. The four Gospels each have a different setting and purpose: the early letters of Paul are indeed largely or completely the work of Paul, an entirely independent mind, and the later letters, together with the Revelation of St John, seem to be equally individual and independent. If these documents do cohere and converge, it is not – as in the Old Testament – because someone smoothed them into a harmony.

However, there is another way in which harmony can be created, and that is by selection. Does the New Testament represent all the writings of the early Christians?

The New Testament as we have it represents works composed before (say) 120 AD – and for the most part before 100 AD. Do we know of any accounts of Jesus from this time that are not included? There is only one, the so-called ‘Gospel of Thomas’, a collection of sayings attributed to Jesus that was (re)discovered in the Nag Hammadi finds in Egypt in 1945. The date of original composition is uncertain, and the contents, though in a few cases very recognisable, are often extremely strange. Certainly it does not seem a great loss to the New Testament.

So the early Church used all, or almost all, the material they had to hand in order to put together a canon. How was it used? Interestingly, the first canon that we know of was proposed around 140 AD by Marcion, who declared that Christianity was discontinuous with Judaism and that the Christian God of universal benevolence was entirely different from the vengeful tribal God of the Old Testament. (This may strike some readers as rather familiar …) Accordingly, and crucially, his canon did not contain any works from the Old Testament.

The response was immediate and decisive. Marcion’s canon was rejected and Marcion himself excommunicated. By 200 AD there was agreement on the backbone of the present Bible – not just four Gospels and ten Epistles, but also the whole of the Hebrew Bible or Old Testament. Some of the Epistles remained in dispute, but the final New Testament canon as we have it now was definitely established by 367 AD.

What of the post-100 AD writings that did not make it into the canon? There are a lot of them! It seems that there was a tremendous appetite for materials to fill the gaps in the four Gospels. Thus we have apocryphal stories of the infancy of Jesus: of his descent to Hades, including the raising of Adam, the patriarchs, and the prophets; of his resurrection; of the (further) acts of the apostles; of the further career of Pilate; and apocryphal letters, apocalypses, and revelations. What can we say about these voluminous writings from the period 100–300 AD?

First, that they reflect the concerns (and curiosities) of the early Christians – their passionate appetite for the ‘back story’ behind the Gospel. These are the Hello magazine, the Facebook, the blogs and tweets, of their time. They are personal, magical, emotional, sensational. Good characters are caught up into heaven, wicked characters are immersed to their knees (very wicked ones to their necks) in boiling lava, pus, or faeces, and the star performers of the Gospels and Acts get a sequel, or a prequel, to ensure that every possible information gap is filled. Some of these stories are exceedingly odd. In the ‘Infancy Gospel of Thomas’ (IGT), for example, the child Jesus strikes down two teachers who have offended him (IGT 14, 15:7), and kills a number of fellow pupils who irritate him (IGT 3:2). Pontius Pilate is presented in such a positive light in ‘Paradosis Pilati’ that the Coptic and Ethiopian churches have made him a saint. In the ‘Acts of Paul’, a lion is baptised; in the ‘Acts of Peter’, Peter revives a dead fish; and in the apocryphal ‘Acts of John’, the hero rebukes bedbugs who have interrupted his sleep, and one of the characters attempts to rape a corpse.

Secondly, they remind us of the struggle in the New Testament – and the Hebrew Bible – between realism and romance. Looking at the Acts of the Apostles after reading the apocryphal version of the same stories, we recognise in the canonical text so many examples of the same urge to romantic exaggeration: the way that Peter’s shadow and Paul’s handkerchiefs cause miraculous cures (Acts 5:12–16, 19:11–12), the magical disappearance of Philip after baptising the eunuch (Acts 8:39), the striking dead of Ananias and Sapphira (Acts 5:1–11), the thrilling sea stories (Acts 27) – all these remind us that sacred myth and secular romance, scripture and folktale, obey very similar conventions.42

The third point to make in relation to these post-New Testament writings is a simple one. They are of interest to the scholar, and to the author of The Da Vinci Code. They need not detain the rest of us!

Footnotes

a. Bishop Papias in the early 2nd century, less than 50 years after Matthew and Luke wrote, tantalisingly refers to an Aramaic collection of Sayings of the Lord made or used by Matthew.

b. This is Luke’s misunderstanding of the phrase ‘speaking in tongues’.

c. To my surprise, I find that Stevie Smith’s poem was actually composed about Mark’s Jesus, but it fits John’s so well that I have borrowed it for that purpose.

d. ‘Friend’, alas, is not what it seems: the word here and in 19:12 is used in the sense of ‘client’ or ‘subordinate partner’, rather than the equal relationship we always assume. See New Oxford Annotated Bible, p. 1907. The passage is a striking example of a translation that is better than the original …