7. Who did Jesus think he was?

‘On the eve of Passover they hanged Yeshu [Jesus] and the herald went before him for forty days saying, “Yeshu is going forth to be stoned in that he hath practised sorcery and beguiled and led astray Israel. Let everyone knowing aught in his defence come and plead for him”. But they found naught in his defence and hanged him on the eve of Passover.’

(Babylonian Talmud, 5th–6th century AD)a

No study of the New Testament can avoid the central question – who was Jesus? In this final section I want to ask three questions. In each case I shall look for answers, not in the sphere of faith, but in the domain of scholarship: not in the Bible as sacred text, but in the Bible as historical record.

The first question is, who did Jesus’ hearers think he was? What categories did they have to understand and interpret him and his message?

Secondly – a question that has much exercised recent New Testament scholars – why was Jesus crucified, yet his followers were not?

And finally, and most ambitiously – who did Jesus think he was?

The Christ of faith and the Jesus of history

Let us begin by defining our terms. For over a century, scholars have distinguished between the Christ of faith (the divine figure worshipped by believers) and the Jesus of history, the man studied by historians. The Christ of faith looks forward to our times and beyond. The Jesus of history looks at his own times, and in a sense we see only his back: his gaze is turned to the men and women of his own time, whose language he had to speak, and whose beliefs he had to understand, in order to convey his message.

This book is not intended to examine the Christ of faith: it can speak only of the Jesus of history. The writers of the New Testament – most strikingly in the case of Paul, but very evidently in all the Gospel writers – had no interest in the historical Jesus. As Paul Beeching puts it, their eye was firmly on ‘the truth of meaning’ rather than ‘the truth of reference’ and ‘their gospels were … exercises in theology’.43 It might therefore seem that all hope of historical accuracy is lost; but that would be a mistake.

First, we know that some elements of the New Testament (as with the Old) are there because they are inconvenient truths that the Gospel writers couldn’t set aside. The towering presence of John the Baptist, forerunner and baptiser of Jesus and leader (both during and after his life) of a rival cult; the insistence that the message was only for Jews; the urgent predictions of the imminent Second Coming; even the crucifixion itself – these are historical icebergs, too big to break through, that the narrative has to navigate around. Second, these texts are of their time – within a century of the events they are writing about – and can tell us much of the circumstances, the assumptions, and the beliefs, of Jesus’ own period. And finally, if they record the beliefs and expectations of a rural Galilean audience, then inevitably they record, at least in part, the beliefs and expectations of their rural Galilean hero.

So let us look at the events of Jesus’ life from a strictly historical viewpoint, trying to sift the Jesus of history from the Christ of faith.

The Christ of faith |

The Jesus of history |

Ancestry, birth, descent into Egypt |

|

Baptism by John Preaching Incident in Temple Entry into Jerusalem Final meal Arrest at Gethsemane Appearance before high priest | |

Trial before Pilate |

|

Condemnation by Jewish crowd |

|

Crucifixion | |

Burial |

|

Resurrection |

There is no intention here to suggest that the events of the left-hand side did not happen; only that however visible to the eye of faith, they cannot reliably be inspected through the lens of history.

Miracles

One element missing from the list above is ‘miracles’. Miracles are a much misunderstood topic. Non-believers discount them as proof of the falsehood of the Gospel; believers emphasise them as proofs of the holiness of Christ and his closeness to, or indeed identity with, God.

Both are mistaken.

Miracle: ‘a surprising or welcome event that is not explicable by natural or scientific laws and is therefore considered to be the work of a divine agency’ (Oxford English Dictionary). Since the 18th-century Enlightenment we have become conditioned to think of miracles as happening far outside the sphere of normality. But the ancient world did not think in this way. (Nor, if we judge by Hamlet and Macbeth, did the Elizabethans!) Miracles were a surprise and a source of amazement (‘miraculum, object of wonder’, OED). But plenty of people claimed to be able to perform them. Jesus performed miracles, but he was able to pass this skill on to his disciples (‘They cast out many demons, and anointed with oil many who were sick and cured them’, Mark 6:13 and similarly in Matthew and Luke), and they in turn passed the power on to others in Acts (where, as we have seen, even Paul’s shadow and Peter’s handkerchief can heal disease). Geza Vermes records the miracles of Honi the Circle Drawer and Hanina ben Dosa.44

And if good guys – Moses, Elijah, Elisha – could perform miracles, so could bad guys: Pharaoh’s wise men and sorcerers turned their staffs into snakes (Exodus 7:11–12), and Simon Magus amazed the people of Samaria with his magic (Acts 8:9–11). Power was not confined to magicians: Roman emperors, Greek sages (Apollonius of Tyana was said to have raised a girl from the dead), and even English monarchs performed wonders – the King’s Evil is the medieval name for a skin disease that the ruler’s touch was believed to cure. And power was not confined to the powerful: itinerant wonder-workers, practising magic for a fee, were a regular feature of rural life in Galilee. In short, and however strange to us today, magic and miracle – the one done by ‘them’, the other by ‘us’ – are part of the fabric of the ancient world: they are not a proof of special holiness, and certainly not of divinity.

So Jesus’ hearers believed that he performed miracles. Who would his hearers have thought he was? What was in the minds of the cheering crowds who strewed palm leaves before him and cried ‘Hosanna’ (‘Save us’) as he rode into Jerusalem on a donkey? The answer is of course that they thought he was the messiah – the anointed of the Lord, come to restore Israel to her ancient greatness and to throw off the yoke of Rome. We cannot tell if they expected him to be a peaceful messiah, an Elijah or a Moses, or a warlike messiah in the mould of King David: but the crowds who had followed Theudas and the Egyptian (see page 130), who would soon rally to the defence of Jerusalem, and who would a century later fight in the rebellion of Simon bar Kochba, were animated by the same expectation of divine support and divine power. The people of Jesus’ time had no expectation of a crucified messiah and no framework to fit one into: the crucifixion would have proved to them beyond doubt that Jesus was not the messiah.

The Jesus of history: how Jesus saw himself

If the Jewish crowds projected their own expectations onto Jesus, who do modern historians think he believed himself to be? I shall confine myself to the writings of scholars who are also believers and so have no atheist or agnostic axe to grind. After nearly a century in which historians felt the topic was exhausted, there has been a huge resurgence of interest in the quest for the historical Jesus. He is seen as a Cynic philosopher, as a Jewish sage, as a political agitator and rebel with an agenda of social justice, and as a passionate prophet of the approaching End Time.45 In addition a Jewish perspective has been provided by Geza Vermes, whose Jesus the Jew (1973) has probably been the greatest single influence in the field since Albert Schweitzer.46

And we should not forget that he is still seen by millions of Christians around the world in the way that St Paul, St Augustine, and Martin Luther saw him, and as the Pope and the present Archbishop of Canterbury see him now – as the inspired Son of God.

Here are some of the key questions that we have to answer if we are to understand, not just how Jesus was seen in his own times, but how he saw himself.

- Was his kingdom a heavenly one, or of this world?

- Was his mission to all humanity, or only to Jews?

- Was it for an infinite ‘all time’, or an approaching End Time?

- Did he will his own death, or was it a tragic accident?

- Did he die to wipe the slate clean, sacrificing himself for all mankind and redeeming ‘the fall of Adam’?

- Did he rise from the dead?

- Was he God and Man, or only human?

These are sensitive and difficult questions. Our task here is simply to ask what light we can cast on them by a careful and detached study of the Gospels. To each question the Christ of faith answers yes (or chooses the first option). What would the Jesus of history have said?

My answers are based on two authors. Their work is entirely independent – neither refers to the other – and their religious views are not explicit in their work. One is Paula Fredriksen, particularly From Jesus to Christ and Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews. The other is Reza Aslan, author of Zealot. Both authors read the Gospels closely, almost as they would a detective story, looking for clues, for indications that all is not as it seems, for what is not said as well as what is. Aslan in particular looks at a number of anomalies in the way Jesus is described in the Gospels, and sets out to find an explanation that will make sense of them.

The first point he draws attention to is Jesus’ repeated use of the terms ‘Son of Man’ and ‘Kingdom of God’. Son of Man is used 81 times in the New Testament: 80 of those occurrences are in the Gospels (the remaining occasion is by Stephen, Acts 7:56). ‘Kingdom of God’ is likewise very restricted in its use, in this case almost entirely in Mark, the earliest Gospel. Both phrases have largely dropped out of the story of Christ but seem very important to the historical figure of Jesus.

The second point is Jesus’ relentless criticism of the Jewish establishment: his praise of the poor, and his bitter condemnation of the rich Temple authorities. This is not simply the battle against the Pharisees – as we have seen, in Luke’s Gospel relations with the Pharisees are quite good. If Jesus had been a simple Jewish nationalist, he would have turned his fire against the Roman occupiers. Why should he be so consistently opposed to the Jewish priestly establishment of the Temple?

Third is the way miracles are treated in the Gospels. Though Jesus is well able to perform such acts, he seems increasingly reluctant to do so. He insists that these actions are not just ‘works of power’ (the phrase used by writers of the time for such deeds), but also ‘signs’. Signs of what?

Fourth is the importance Jesus attaches to the Twelve, a number that is sufficiently significant to be used both in the Gospels and in Acts, to the point where it is more important than the actual names of those chosen (which differ between the books of the New Testament).

Fifth – as we have seen – is the mysterious ‘messianic secret’, so prominent in Mark, and so much less evident in the later Gospels, as if a historical memory is preserved in the earliest account that becomes overwritten by the later theology.

The sixth anomaly, again one we have touched on already, is the striking (and universally accepted) fact that although Jesus was put to death by the authorities, his followers were not. If he was a threat to the authorities, why did they not act as they did with all the other would-be messiahs, and cut down his followers? And if he was not a threat, why was he executed at all?

The final point is one we have not touched on before. The teaching of Jesus as we have it in the Gospels is seen by those around him as quite surprising. John the Baptist preaches a recognisable message of repentance, and behaves in a recognisable way – solitary, self-denying, ascetic: as joggers like to say, ‘No pain, no gain’. But Jesus’ message, as it comes down to us, did not conform to any pattern that his hearers recognised. He obeyed the Law, but was relaxed about breaches of it; he performed miracles of healing, but did not insist on payment either in money or in repentance; he associated with the rural poor, but also with the urban rich; he lived a pure life, yet was not ashamed to keep company with drunks and prostitutes; his companions included numerous women and he seems to have treated them as equals. Not everything he says is gentle and forgiving; his yoke is not always easy nor his burden always light; yet if we look at what struck his contemporaries about his message, it is hard to find anywhere else in the Bible such a gentle, inclusive, and loving vision.

What identity, what kind of person, do these clues point to?

Let us start with the mysterious references to ‘the Son of Man’. This Aramaic phrase – it translates awkwardly into the Greek of the New Testament – can simply be a way of saying ‘I’, as in ‘The fowls of the air have nests, but the Son of Man hath nowhere to lay his head’. But this definition will not cover every one of the 81 occasions where this phrase is used. In each of the Synoptic accounts of the trial, Jesus is asked if he is the messiah – but responds by deflecting the questions, insisting instead that he is ‘the Son of Man’ (‘ho huios tou anthropou’): note ‘the’, not ‘a’. This ‘Son of Man’ is unmistakeably the figure depicted in the second part of the prophetic Book of Daniel: ‘Behold, one like the Son of Man came with the clouds of heaven, and came to the Ancient of Days [God] … And there was given him dominion, and glory, and a kingdom, that all people, nations, and languages, should serve him’ (Daniel 7:13–14). At this crucial moment, Jesus is asked whether he sees himself as the messiah – a title with huge resonance for any Jew of that period – and emphatically insists that his preferred title is Son of Man. In Mark he even quotes Daniel directly: ‘coming in the clouds of heaven’ (Mark 14:62).

It seems, then, as though the Jesus of history – or at least the Jesus of the New Testament – saw himself, neither as God, nor as prophet, but as the figure appointed by God to restore Israel to its former glory and to install on earth the Kingdom of Heaven. This is the task of the Davidic messiah predicted in Zechariah: of a man who enters Jerusalem triumphant but also humble, powerful but also peaceful, and riding, not in the horse-drawn chariot of war, but on a donkey (Zechariah 9:9–10).

What kind of kingdom would this be? It would be unlike anything we know from history. It would be an ethical kingdom, living by the rules of the Sermon on the Mount; a just and equal one, in which the poor are blessed; a kingdom in which ‘all things are possible’ (Mark 10:27). And who better to rule it than the Son of Man as imagined by Mark’s Jesus: a figure who is rejected (10:33) yet will judge (14:62), and who is both suffering servant (8:31, 10:45) and powerful ruler (8:38)?

What is the dominant quality of this kingdom? It is not independence. We are not looking at a simple freedom fighter. The essential ingredients are zeal and love. Love for one’s fellow Jew: note that Leviticus 19:18, ‘the golden rule’, is not that one should love all men as oneself, but that one should love one’s co-religionist in that way (which is why Jesus was so emphatic that he came to save ‘the lost sheep of the house of Israel’). And zeal, pure passion, conviction, and courage, without which nothing can be achieved because Jesus does not dispose of any army. Zeal is the overwhelming power of the righteous – the pearl of great price, the readiness to sacrifice all that one has for righteousness and purity: ‘Blessed are they which do hunger and thirst after righteousness: for they shall be filled’ (Matthew 5:6). Zeal springs from the vision of the people of Israel living as they should; and zeal is offended by the sight of the Temple authorities living richly off the contributions of the poor.

There is evidence that social inequality was growing in Jesus’ time and that the power and wealth of the priestly establishment was increasing. Jesus’ target was not the Roman occupier, who couldn’t be expected to know any better. His target was the great and the good of his own nation – who could. His miracles, like the NHS of our own times, were free at the point of delivery. Priestly healing was not. A leper made clean by a priest had to pay a considerable fee (including two birds and three lambs, Leviticus 14); Jesus and his disciples healed without charge. ‘Heal the sick, cleanse the lepers, raise the dead, cast out devils: freely ye have received, freely give’ (Matthew 10:8, emphasis added). When Jesus heals a leper and tells him to show himself to the priest and make an offering for his cleansing, he is highlighting the contrast between his own approach, and the greed of the priestly classes. Aslan suggests47 that to Jesus’ audience, the most striking feature of the parable of the Good Samaritan would not have been the goodness of the Samaritan, remarkable though that might be. It would have been the badness of the priest and the Levite.

How would the Kingdom of Heaven be established? We have referred earlier to the ambiguity of the New Testament attitude to violence. There is nothing in the Gospels to suggest that Jesus saw violence as his first recourse. But as we have seen earlier, there is plenty of evidence that he recognised that the use of force towards the Roman occupier might be a necessary price to pay.

Three texts are particularly telling here. Each is traditionally interpreted as a pointer to the spiritual, other-worldly nature of the kingdom; but there may be more than meets the eye.

When Jesus is asked the famous question about the Roman coin (Matthew 22:21, Luke 20:25), his answer is often given as ‘Render’ – in other words, ‘Give’ – ‘to Caesar, that which is Caesar’s’. But the Greek word is ‘Apodidiomi’ – ‘Give back, restore to where it rightfully belongs’, and the quotation continues, ‘and [render] to God the things that are God’s’. In other words, Caesar’s coin should be restored to Caesar – and what is God’s, in other words the kingdom of Israel, should be restored to the people of Israel, its rightful owners.

When Jesus instructs his followers to ‘take up [your] cross, and follow me’ (Matthew 16:24, Luke 9:23), we have learned to think of this as an invitation to self-sacrifice, to walk the Golgotha road. That is not what it would have meant to his audience. They know that crucifixion was a political sentence – the punishment for rebellion. It is not a call to suffer: it is a call to become rebels.

Finally there is the enigmatic response to Pilate, ‘My kingdom is not of this world’ (John 18:36). My edition of the New Oxford Annotated Bible glosses this as ‘the kingdom of Jesus is other-worldly, and no threat to Rome or Judea’, and that is how it has been read in the past (not least because it is so consistent with the message of John’s gospel). But many scholars – notably Rowan Williams, former Archbishop of Canterbury – read the Greek differently. Williams accepts an alternative translation, ‘my kingdom is not of this sort’ or ‘not of this kind’, and comments, ‘this kind of royal authority is inseparable from the task, the calling, of embodying truth’.48 If this is right, Jesus is not standing back from power and authority in this world: he is standing back from power and authority of this kind. What kind of kingdom would his be? The Kingdom of God – the one soon to be installed in Israel by the Son of Man, with its restored twelve tribes headed by the twelve apostles.

Let us turn now to the miracles – the signs and wonders that the Gospels record Jesus as having performed. The traditional way of seeing these is as good things in their own right: as love in action. If any of us had the capacity to heal blindness or epilepsy, or to feed the starving, would we not use it? And this is certainly one way in which Jesus uses his powers – out of kindness (Matthew 14:14 and 20:34, Mark 8:2, John 11:35 and 38, for example).

But it is puzzling that Jesus seems increasingly impatient, even irritable, with simply performing miracles. How can we explain this apparent ‘compassion fatigue’? Reza Aslan convincingly suggests that ‘his miracles are not intended as an end in themselves … they serve a pedagogical purpose. They are a means of conveying a very specific message to the Jews’.49 The message is that the Kingdom of God that the Son of Man will usher in, has already arrived. When the followers of John the Baptist ask Jesus, ‘Art thou he that should come, or do we look for another?’, Jesus does not answer with a simple yes or no. He quotes from Isaiah 35:5–6 to show that the miracles are evidence of the actual presence of the Kingdom here and now: ‘The blind receive their sight, and the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, and the deaf hear, the dead are raised up, and the poor have the gospel preached to them’ (Matthew 11:1–6, Luke 7:18–23: note the reference to ‘the poor’).

What of the Resurrection? The Resurrection is not just significant in itself: it is another sign that the End Time has arrived. ‘I will open your graves’, writes Ezekiel (37:12). So powerful is this belief that Matthew extends it beyond Jesus to others: ‘And the graves were opened: and many bodies of the saints which slept arose’ (Matthew 27:52). If we took this passage at its face value, we might expect that people who had been restored to life in this way would be brought forward to bear witness to the power of Jesus. In the event there is no further mention of them in the Gospel or in Acts.

Jesus’ resurrection does not return him to normal life as if he had never died: that is not the point. Its symbolic importance is greater than its actual. As ‘the first fruits of them that slept’ (1 Corinthians 15:20), it demonstrates that other fruits will follow, that the Kingdom has arrived, the time when, as Daniel puts it, ‘many of them that sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake’ (Daniel 12:2).

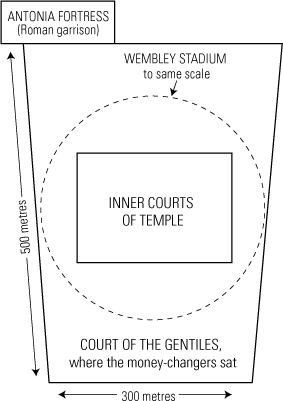

Finally, what of the so-called Cleansing of the Temple, the turning over of the tables of the money-changers? Up till recently Bible scholars tended to accept the view of the Synoptics, that it was a very shocking and public event that provided the stimulus, the trigger, for the arrest and crucifixion of Jesus. But more recent commentators challenge this view. They point out that the Court of the Gentiles (the outer courtyard of the Temple) where the cleansing would have taken place was enormous (as big as a dozen football pitches) and would have accommodated tens of thousands, indeed hundreds of thousands, of pilgrims. To overturn a few tables and release a few birds (the big animals were kept outside) would have been a trivial event, a minor scuffle far too small to have had an impact on public opinion or to constitute a challenge to the priesthood or to the Romans who guarded the Temple precincts. But what if it did not symbolise cleansing, but destruction? The destruction and rebuilding of the Temple is a recurring theme of Jewish apocalyptic writing – a sign that the Kingdom of God is at hand.50

Diagram 8. Herod’s Temple in Jerusalem (started 20 BC, destroyed by the Roman army 70 AD), the scene of Jesus overturning the tables of the money-changers. For comparison, Wembley Stadium (which seats 90,000) is shown to the same scale.

These hints in the text point to a Jesus who believed himself to be Daniel’s Son of Man, the coming Saviour of the Jews. Such a Jesus would not himself be a danger, because the kingdom he preached would be brought about by act of God, not by force of arms. But the expectations placed upon him by the cheering Passover crowds made him a dangerous figure – not only to the Roman occupiers, but also to the wealthy priesthood, the ‘theocracy’ (as Josephus describes them) who controlled the revenues of the Temple.

If, as Paula Fredriksen suggests,51 Jesus had ‘lost control of his audience’, it would not be surprising for the Jewish establishment to hand him over to the Romans for execution. But why did the Romans, contravening their usual policy, not pursue his followers also?

This is where the ‘messianic secret’ falls into place: the deliberate concealment of the miracles, and the deliberate obscurity of the parables, that is so pronounced in Mark. The evangelists told a story about a crucified and risen Son of God bringing salvation to mankind; they did not tell a story about Daniel’s Son of Man, bringing in the Kingdom of Heaven on earth and restoring their rightful place to Jews, because Jesus had successfully concealed it from them, and not only from them but also from his disciples. Why did he do that? Because that was the only way in which he could protect them and ensure that when his own death came, he would not pull them down in the wreckage. As far as the Roman and the Temple authorities were concerned, Jesus was a prophet, a wonder worker, and a teacher; but (as John’s account makes plain) they had seen him regularly in Jerusalem at Passover, and knew that he and his followers were harmless. This year the crowds got out of control, welcoming him as messiah and Son of David. That was too much; public order was threatened; he had to go. But there was no need to take his followers with him.

This account of the Jesus of history rests heavily on Reza Aslan’s stimulating and closely argued Zealot. For all its originality – and the challenges it poses to orthodoxy – Aslan’s account solves a number of puzzles, and builds elegantly on the work of other scholars.

And there is another reason why I think we should take Aslan’s account seriously. The Christ of faith – Son of God, Maker of Heaven and Earth, Redeemer of Mankind, Vanquisher of Satan – is a wonderful creation, to be admired whether or not he is believed in. But we have to account for the fact that the Jesus of history was likewise a man loved and admired by his followers. The zealot pictured here (Aslan is at pains to point out that ‘zealot’ is with a small ‘z’, not the fully fledged Zealots of the political movement of 50–70 AD) – passionate, visionary, generous, and brave – would be a man worthy of such respect: of their respect, and of ours.

Footnote

a. I am grateful to John Clarke, former Dean of Wells Cathedral, for this reference.