3. The sum of the parts: reading the Bible as a unity55

The three extracts above show, I hope, that the tools of literary criticism can fruitfully be used to increase our appreciation of the qualities of the Bible. But there is a risk that this will end in a kind of cherry-picking, seeing passages in isolation, and selecting only those passages that we find of merit. Images and phrases from the Bible – ‘a house built on sand’, ‘a still small voice’, ‘tablets of stone’, ‘risen from the dead’, ‘the grapes of wrath’ – resonate with us, and even single words (‘exodus’, ‘resurrection’, ‘revelation’) come with a rich freight of associations. But it is not just these fragments, these cherries, that exercise an influence.

The Bible remains stubbornly present in the centre of our literary and imaginative experience, just as churches and cathedrals are unmistakable features of the skyline of our cities, towns and villages. It is easy enough to understand this in the case of musicians and painters. Painters use images and musicians use sound, but their art makes no direct statements about reality: to depict a Madonna and Child, carve a Nativity, or write the music for a Christmas oratorio does not require belief in the virgin birth. But what of writers? Dante, Milton, and Eliot wrote from within the charmed circle of faith, but what of Byron? Shelley? Pound? Yeats? Kafka? Bulgakov? D.H. Lawrence? Steinbeck? Gide? Camus? Henry Miller? Robert Heinlein? Philip Larkin? What was it in the Bible that so stimulated the imagination of these writers, none of whom in any meaningful sense could be called Christian? Why is it that Negro spirituals, for example, call on Moses to free them – even though the slaves in the cotton fields had never been anywhere near Egypt? Why do The Byrds and Bob Dylan draw so heavily on Old Testament texts and imagery? Why does a rock band call itself ‘Genesis’?

We mentioned churches above. Just as any guidebook will invite us to see the humblest parish church, not just as a collection of windows and carvings, but as an architectural whole – just as we experience in a great public building, whether sacred or secular, a sense of overall design and unity – so we must seek out the overall architecture and shape of the Bible if we are to truly see it. To do otherwise is not only bad literary criticism, but bad Bible criticism.

The first principle of the appreciation of any work of art is that it is a unity. That unity may not be obvious at first sight: but that is the principle that must guide us. The two Appendices show how much editing and rewriting the Bible has undergone, making it ‘probably the most systematically constructed sacred book in the world’.56 In Parts One and Two I used this to argue against claims for any kind of historical truth for the Old and New Testaments. But if we view the work from the perspective of the imagination, we are reminded that editing can be objective, a process designed, not to impose order and unity, but to find it. The good editor can sometimes see what the author cannot, just as the artist can find in the landscape an order that nature has not put there, and the historian, a pattern in events undetectable to those who took part. Editing is a process that works in many ways and on many levels. There is grouping by genre; just as Shakespeare’s works were divided by his first publishers into histories, tragedies, and comedies, so the books of the Old Testament are grouped into Pentateuch, Histories, Prophets, and ‘others’. There is editing by combination, as when the Redactor interweaves the two tales of Noah’s flood into a single apparently unified story. And there is thematic editing and grouping: the Book of Isaiah, despite its title, cannot have a unity of authorship unless Isaiah lived for over 300 years, but it has nonetheless a unity of theme, ‘the parable of Israel lost, captive, and redeemed’.57

The picture ‘Saint Luke painting the Virgin and Child’, a 15th-century miniature from the British Library collection, is instructive in this regard. Saint Luke sits before the Virgin and paints her: but what appears on the canvas is not quite what sits before him. On his canvas, the Virgin’s red hair is largely covered: the child’s pose is more tranquil, less teasing; the mood is more contemplative and reverent than that of the sitters who face him. The painting shows Luke editing what he sees before him to bring out its true but hidden meaning.

We see this editing perhaps most clearly where it has been left incomplete. The opening of John’s Gospel – ‘In the beginning …’ – was unmistakably written in order that the New Testament should open with a creation story to match the creation story that opens Genesis. Alas, John’s Gospel was not only written later than the others (which wouldn’t matter given that Matthew was later than Mark, but is placed before it), but was for many years regarded as of questionable value and orthodoxy, so it never took the pole position for which it was intended.

So we see everywhere evidence of deliberate design and redesign both within and between the Testaments. Anton Ehrenzweig wrote of ‘the hidden order of art’. What is the hidden order that editors detected in the Bible? Rather than trying to view the parts, let us try to look at the whole, and just as we give credit to a church or a cathedral as having a unity of design, let us make the hypothesis that the editors of the Bible too were striving to find and give voice to the unity, the hidden order, lying within its apparent shapelessness. Let us approach it as we approach any work of the imagination – as a unity.

The unity of Old and New Testament: myth …

We cannot begin to make sense of the New Testament, and thereby of the unity of the Bible as a whole, without appreciating the overwhelming importance that the evangelists attached to showing how Jesus fulfils what was ‘foretold in the Scriptures’ – by which of course they meant the Old Testament.

The first term we need in order to understand imaginative works is that of myth (from the Greek ‘mythos’, meaning story). For all its historical content, the Bible is not a work of history; much of what it contains did happen, and therefore features also in works of history, but it is not in the Bible for that reason. Myth, as we will define it here, has two elements. One is imagination – a quality that myth shares with all other forms of fictional writing. But myths have another dimension. They tackle matters that society deems to be important: they cluster around areas of social or existential concern, and the greater the concern – the closer to the central beliefs, and anxieties, of that society – the more they tend to hang together and form that set of interlocking tales that we call a mythology. Classical mythology, which underpinned Homer and Sophocles, clustered round Zeus and the Olympians: it was ‘canonical’ – sacred – to the Greeks. For a Christian audience, it became ‘merely’ mythology. Our own canonical myth is the Bible.

Myth is not history, and mythical thinking – though highly structured – is not rational and analytical thinking. History looks outwards and is judged by its correspondence with external reality. Myth looks inwards and has a different standard of truth: its fidelity is to shape, structure, and meaning. Shakespeare read his historical sources carefully and used them well, but Hamlet and Macbeth are structured as tragedies, myths about kingship. Gibbon’s Decline and Fall is a work of history: but the pattern of rise and fall alluded to in its title – of the tragic hero, of the sun, and ultimately of a sun god – is a mythic one, and retains its literary and imaginative power long after Gibbon’s work has been superseded as history.

History seldom repeats itself: myth always does, because matters of social and existential concern, like the rituals that reflect them, need to be constantly revisited and renewed. Structure – shape, pattern, and above all repetition – is present everywhere in the Old Testament. The most striking example of this is the parallelism between Old and New Testament. Augustine remarked that the Old and New Testaments are a kind of sealed unit, like a pair of mirrors reflecting each other, so that the New Testament lies hidden in the Old, and the Old Testament is revealed in the New. We have examined at length the way in which such correspondence undermines any historical claims made for the Bible. But by the same token, such correspondence only reinforces its integrity and power as myth. When early Christians looked for reassurance about Jesus they were told to go to ‘the Scriptures’ – which meant at that time, not the New Testament, but the Old. (When in 140 AD Marcion suggested a canon without the Old Testament, he was excommunicated.) We have seen the tremendous efforts made by the evangelists and the writers of the Epistles to create their own Old Testament ‘prequels’. Historically speaking there was no evidence to find: but mythical evidence is of a different kind.

The myth of deliverance: synchronising Old and New Testaments

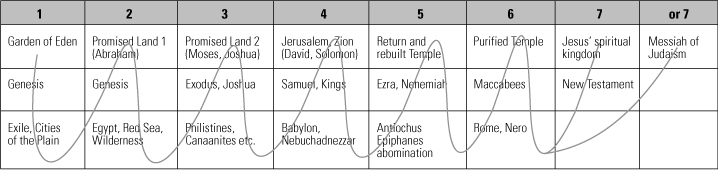

The core myth of the Bible is the myth of deliverance: the U-shaped fall and rise of descent and recovery. Let us examine this by picking out seven such narrative structures in the work (there are more, but these will do!).

Diagram 9. Fall and redemption (adapted from H. Northrop Frye, The Great Code: the Bible and Literature

(Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1981), used by permission of Victoria University in the University of Toronto).

In each case the top line – the starting point – represents the unfallen world, the natural home of man, the good life lived in harmony with the teaching of God. The bottom line represents the fallen world of exile from that ideal state. In each case there is a ‘deliverance’ from the fallen state up to the recovered good life, and in each case – as we move left to right – there is a new fall from grace. (The line splits at the right-hand end according to whether Jesus is seen from a Jewish or a Christian perspective.) Each of these events is a myth, whether or not it is a historical event: the historical pattern is at best doubtful, but the structural, that is mythical, shape is impossible to miss.

If the core myth of the Bible is deliverance, then the core myth of deliverance is Exodus, and if we are to understand why the writers of the New Testament draw so heavily on the Old, this is where we need to start. So many puzzles in the Gospels become clear when we understand the urgent wish of the evangelists to conform the life of Jesus to the patterns of the Old Testament. The child Jesus descends into Egypt with his parents, and (in John’s Gospel) descends into human form, just as the Israelites descend into captivity in Egypt. The Passion is synchronised with the Passover, calling to mind the Passover deliverance of the Israelites. The sacrifice of the firstborn in Exodus is echoed not only in Matthew’s Slaughter of the Innocents, but in the crucifixion itself. At the Passover, the firstborn is replaced by a lamb, giving rise to the identification of Jesus as ‘the lamb of God’. Before the crucifixion comes the curious episode when the mob choose Barabbas over Jesus, a ‘tradition’ without any precedent in Roman or Jewish custom: this becomes much easier to understand in terms of a kind of ‘younger brother’ (Barabbas means ‘son of the father’, in other words ‘brother’, in Aramaic), reminding us of the recurring theme of fraternal rivalry and supplanting of the firstborn (Cain/Abel, Ishmael/Isaac, Esau/Jacob) running through the Old Testament.a

The Christian ritual of baptism, submerging the believer so that they can emerge into new life and leave their sins behind, echoes the Israelite crossing of the Red Sea and their escape from captivity into freedom.

While in the wilderness the Israelites are troubled by serpents and ask Moses for help; he raises a healing serpent on a staff (Numbers 21:9), prefiguring the elevation of Jesus on a cross as the healer of his people. How long does Moses spend on Mount Sinai writing down the words of the Lord? Forty days. How long does Jesus spend in the wilderness on his way to save the world? Forty days. How many tribes leave Israel? Twelve. How many disciples does Jesus appoint? …

There are many more examples but it would be tedious to cite them all.b

The point is that for the New Testament writers and their readers, the events of the life of Jesus had no meaning unless and until they corresponded with a prefiguring event in the Old Testament. This approach to Scripture is known to scholars medieval and modern as ‘typological’ or ‘figural’, and it explains why for a century or more after the death of Jesus, the ‘Scripture’ to which believers were referred for illumination about the life of Christ was not the evolving New Testament, but the pre-existent Old Testament, written before Jesus was even born. Beneath this ‘figural’ approach lies a belief in the deeper meaning of events, rather than the surface: ‘The Gospel writers care nothing about the kind of evidence that would interest a biographer – remarks of disinterested travellers and the like; they care only about comparing the events in their accounts of Jesus with what the Old Testament, as they read it, said would happen to the messiah … [Their view is that] This may not be what you would have seen if you had been there, but what you would have seen would have missed the whole point of what was really going on.’58

Metaphorical thinking

Mythical thinking is also metaphorical thinking. A metaphor is something that stands for something else: Egypt stands for captivity, the lamb for Jesus, the cross for salvation, the city of Jerusalem for the Heavenly City. In the diagram above, each item on the top line is a metaphor or ‘type’ for the ideal condition of man, his true home, and each item on the bottom line for the fallen state of man, his life in exile and captivity. As such, all the high points are metaphorically identical with each other, and likewise all the low points. ‘The garden of Eden, the Promised Land, Jerusalem, and Mount Zion are interchangeable synonyms for the home of the soul, and in Christian imagery they are all identical.’59 And what they are identical with, for New Testament writers, is the Kingdom of God that Jesus spoke of. (From a Jewish perspective, the Hebrew Bible points likewise to the redeemed world that the Jewish messiah will usher in.) The same is true along the bottom line, where Wilderness and Egypt, Babylon and Rome, are metaphors for each other, and hence, in mythical thought, identical and interchangeable. And the deliverers of Israel along the top line are all ‘types’ of the final deliverer, whether Christian Saviour or Jewish messiah.

In the top line, God, man, and nature are in harmony. The close contact between man and God scarcely needs emphasising, but man stands between a spiritual realm and a natural one, and the relationship with nature takes different forms in the two domains. In the lower world, the relationship between man and nature is one of domination. In this alienated world the task of humans is merely to ‘Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth and subdue it, and have dominion over … every living thing that moveth upon the earth’ (Genesis 1:28). This world of exile and wandering, of thorns and thistles, of human and animal enslavement (‘And the fear of you and the dread of you shall be upon every beast of the earth’, Genesis 9:2), is the fallen world of Egypt and Babylon, of tyranny between husband and wife (Genesis 3:16), and of Ezekiel’s valley of dry bones, into which Jesus traditionally descends after his crucifixion. It is also the totalitarian hell of a world of pointless work designed only to subjugate nature and accumulate wealth: ‘For what shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?’ (Mark 8:36).

Its counterpart in the higher world is the Garden of Eden, where man names the animals as if they were pets, and lives in gentle harmony with the trees and plants. That harmony with nature recurs in the Promised Land, which will be ‘flowing with milk and honey’, in Isaiah’s holy mountain where ‘the wolf also shall dwell with the lamb’ and ‘they shall not hurt nor destroy’ (Isaiah 11:6–9), and in the Book of Revelation, where the river of the water of life will flow through the City of God, and the tree of life will produce its healing fruit (Revelation 22:1–2). The purpose of work in the Bible is to regain that higher world: ‘And when you work with love you bind yourself to yourself, and to one another, and to God … work is love made visible’ (Kahlil Gibran).

Abraham brings his family up out of Ur to a promised land in the West; Moses and Joshua bring the Israelites up out of Egypt and return them to the Promised Land; both are ‘types’ of deliverance. But the New Testament writers need to combine other ‘types’ of authority into the figure of Jesus, notably those of prophet and (given that Israel is a theocracy) king. As king, he is the descendant of David, born in Bethlehem into a humble family; and the evangelists take pains to connect him also to Solomon, builder of the Temple, through the homage of the Wise Men from the East whose gifts echo those brought by the Queen of Sheba (‘And the Gentiles shall come to thy light, and kings to the brightness of thy rising … all they from Sheba shall come: they shall bring gold and incense: and they shall shew forth the praises of the LORD’, Isaiah 60:3–6). As prophet, Jesus fulfils the ‘types’ of Moses (the representative of the Law) and of Elijah, the greatest prophet of the Old Testament but also a ‘type’ of Jesus in his concern for the poor and his ability to raise the dead (1 Kings 17–24): both appear in the otherwise rather mysterious Transfiguration that features in all three Synoptics (Matthew 17:1–9, Mark 9:2–8, Luke 9:28–36). Nothing in the New Testament is there for itself: everything is there to fulfil the Old.

Religion and control

Followers of the three main Western religions – Judaism, Christianity, and Islam – are collectively known as ‘people of the book’, and all three ‘books’ function as rulebooks and instruction manuals for religious and moral orthodoxy. It is commonplace to hear people speak of ‘Judaeo-Christian morality’ and I suspect I have even used the phrase in this book. The sense of the Bible as a book of rules was always there, but – as we have seen – has become more pressing with the rise of Protestant religions (and their Islamic equivalents) which accept no authority other than their own direct and context-free reading of Scripture.

Religion (from the Latin root ‘binding’) is always concerned to demarcate and exclude – believers from non-believers, orthodox from heretics, the saved from the damned, saints from sinners, good from evil, clean from polluted, the sacred from the secular. In like manner, faith is always under pressure to close itself off from doubt. Professed faith is a statement of loyalty – to belief, to practice, and to fellow-believers – and like the soldier preparing for battle, believers must shut out any questioning of their own rightness (and righteousness). Faith strikes a bargain with God, and expects that the bargain will be fulfilled: ‘Honour thy father and thy mother: that thy days may be long upon the land which the Lord thy God giveth thee’ (Exodus 20:12, italics added). And all religions are communities of practice, of rules of behaviour and conduct that members must follow if they are to stay within the community.

Where there are rules, there are enforcers of the rules. All who create and enforce rules – all regulators – must speak with authority, and the Bible is no exception. Indeed it is not an accident that we use the word ‘speak’. The authority of rules is deeply associated for us with speech: military words of command, the Queen’s (or the King’s) Speech, the word of the Lord dictated to Moses, the commandments dictated in turn by Moses to the assembled Hebrews. And the sentence structures and rhythms of such speech are very oral ones, using short sentences with a distinctive, often repetitive rhythm and an absolute confidence and clarity that excludes nuance, explanation, or qualification:

‘Ye have heard that it was said by them of old time, Thou shalt not commit adultery: But I say unto you, That whosoever looketh on a woman to lust after her hath committed adultery with her already in his heart. And if thy right eye offend thee, pluck it out, and cast it from thee: for it is profitable for thee that one of thy members should perish, and not that thy whole body should be cast into hell. And if thy right hand offend thee, cut it off, and cast it from thee: for it is profitable for thee that one of thy members should perish, and not that thy whole body should be cast into hell.’ (Matthew 5:27–30)

The Sermon on the Mount – for which the ‘type’ is the Ten Commandments, also delivered on a mount – speaks the simple language of vision and prophecy. But rules are always more complex in the application than in the announcing, and require in practice much interpretation, qualification, and glossing.

The process of clarifying, interpreting, and qualifying, of turning the inspiration of prophecy into the rules and regulations of religion, is the work of scribes. The writings that interpret the Torah (the midrash) are longer than the Torah itself, and the hadith and tafsir likewise longer than the Qur’an. The Gospels remind us that Jesus spoke often, but wrote only once, and it is not accidental that he wrote in sand (John 8:6–8), emphasising the paradox that the spoken word can sometimes last longer than the written. What scribes do is scribble. What prophets do is prophesy.

But it is not only law-givers (and dictators) who speak with authority. So do oracles. And if we reframe this authoritative voice, not as the dictatorial voice of the law-giver, but as the oracular and inspired voice of the prophet and seer, we get a very different perspective on what is being said. What if, instead of rules, the prophets are giving us a vision? What if, instead of the written and codified tyranny of organised religion – the written script of how things should be – we are hearing instead the inspired and authentic spoken voice of how things might be: a vision of a world without killing or deception, of a society without tyranny or injustice?

Read this way, the Bible becomes a very different book: different not because the words are different, but because the purpose, the meaning, and the context of the words have changed. Visions, like compass bearings, are directions, not destinations: there, not to arrive at, but to steer by. Isaiah’s holy mountain cannot be found on any map, nor is it surrounded by signs forbidding killing. ‘[In this reading], “Thou shalt not kill” … is less important as a law than as a vision of an ideal world in which people do not, perhaps even cannot, kill … many of Jesus’ exhortations … are not guides to practice … but parts of a vision of an “innocent” world, and it is that vision which is the guide to practice.’c 60

We know about vision, oddly enough, because we respond to it in the inspirational speeches of politics. ‘We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender’, is not a battle plan. ‘A rainbow nation’ is not a statement about demographics. ‘Government of the people, by the people, and for the people’, is not a worked-through constitutional proposal, and ‘I have a dream’ is not a White Paper on racial integration. They are all phrased – both in their syntax and in their impact – as prophecies; as authoritative statements of how things could be; as visions.

When in the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5:32) we read, ‘Whosoever shall put away his wife […] causeth her to commit adultery’, we recognise the authentic voice of prophecy. But where the brackets are, someone has inserted a qualifier, ‘saving for the cause of fornication’. As Northrop Frye memorably puts it, ‘Some scholars think that [that] phrase … is a later interpolation. One reason why they think so is stylistic: the cautious legal cough of parenthesis has no place in a prophetic style, but is a sign that someone is trying to corrupt the gospel into a new law.’61 The voice of prophecy is the roar of the lion, not the officious chatter of the squirrel. Corrupting a Gospel into a law is a recipe for tyranny, a choice, in the words of Deuteronomy (30:19), of death over life.

The Bible and dissent

Where religion seeks to control, vision seeks to liberate. The imagination, which is where vision resides, is always in opposition because its limits are not the permissible, but the conceivable. The real-world settings of so much of the Bible, its profound if problematic immersion in history, together with its concern for the underdog, mean that its vision will always challenge the rich and the powerful. The Torah enjoins charity to widows and orphans, and reminds the people of Israel that even when they are installed in their Promised Land, ‘Love ye therefore the stranger: for ye were strangers in the land of Egypt’ (Deuteronomy 10:19). Jesus remarks on the widow who drops her mite in the Temple collection box (Mark 12:41–44, Luke 21:1–4) and in doing so, condemns the rich and powerful who could give so much more.

This profound feeling for justice marks a huge area of common ground between the Bible and literature. Myths are where the poetic imagination meets social concern: and that is where artists, writers, and poets work. When John Steinbeck was outraged by the treatment of itinerant farm workers in the Midwest, he kept much of the content of his novel as close to realism as he could, and indeed the story (and the history) are shocking and distressing enough to need no embroidery. But by choosing to call his book The Grapes of Wrath, he connected the pathos of humble Okie sharecroppers to a greater story. The grapes of wrath feature in Julia Ward Howes’ ‘Battle Hymn of the Republic’ from 1861, linking these ordinary men and women with the mighty struggle to free the slaves and beyond that with the sacrifice made by Christ (‘As Christ died to make men holy, let us die to make them free’); and that in its turn points to ‘the great winepress of the wrath of God’ (Revelation 14:19–20) and the conviction that what awakes the anger of God is above all injustice. And behind the realism of content in Steinbeck’s book is a further mythical structure equally charged with echoes and resonances. The journey to California becomes a failed Exodus, the name of the heroine (Rose of Sharon) points us to the Song of Songs, and the extraordinary ending where she feeds the starving old man with her own milk echoes Lot’s daughters baring their young bodies to their ageing father. The preacher Jim Casy (the initials are a pointer) loses his faith and turns away from his former life: but by his death seeking to ‘speak truth to power’, he becomes a figure of Christ.

‘And it came to pass, when Ahab saw Elijah, that Ahab said to him, “Art thou he that troubleth Israel?”’ (1 Kings 18:17). The priestly establishment supports kingship (and indeed eventually turns into the theocracy of Jesus’ time), but Elijah was a prophet, and the prophets of the Old Testament are a notoriously rebellious bunch, well known for their habit of speaking truth to power – whatever the cost to themselves. Moses, and before him Abraham, bargain and negotiate with God; Nathan confronts David; Elijah confronts Ahab; in the New Testament, John the Baptist pays with his head for the threat he represents to Herod. And there is in the Old Testament a general uneasiness about power, a sense that if not now, then soon, it will end in tears. Samuel, following the advice of God, warns the Israelites against appointing a king to rule them (1 Samuel 8); they choose not to take his advice but it is soon proved to have been correct. The Deuteronomist, similarly sceptical about the whole business of kingship (Deuteronomy 17:15–20), observes the actions of the successive kings of Israel with disapproval, consistently marking them down for their failure to centralise sacrifice in Jerusalem and keep to the strict letter of the Law: kingship, he seems to suggest, may be necessary, but it is a necessary evil.d

When the priest Hilkiah finds the celebrated scroll of the Torah in Deuteronomy in 622 BC and arranges for it to be read to the young King Josiah, it is the king who weeps and rends his garments: and what is more, it is the king, not the priest, who insists that it must be brought to the knowledge of the people, the work of being the chosen ones of God being for all the people, not just the priests.

As we might expect, the revolutionary forces in the Old Testament become focused in the condensing mirror of the New, where even in the Temple itself God is praised as the one who ‘hath put down the mighty from their seats’ (Luke 1:52). Jesus’ constant campaigns against the Temple establishment are well known, as is his insistence that the disciples are never to join the cosy group of those who conform: ‘Woe unto you, when all men shall speak well of you!’ (Luke 6:26). His statements that he comes not to bring peace but a sword are played down by evangelists and St Paul alike; but we notice that although Paul enjoins Christians to accept and obey the laws of the land, he does not want them to set their moral compass by those laws. As in the Old Testament, what you find in ‘high places’ is ‘spiritual wickedness’ (Ephesians 6:12). And when we get to Revelation we are left in no doubt: Rome – like Egypt, like Babylon, like the Cities of the Plain – is the seat of Antichrist.

Imagination and vision

Is this a programme for political action, a kind of early Marxism? By no means. Read in this way, the Bible is not revolutionary in the sense that Chairman Mao or Islamic State are revolutionary, blueprints for an earthly kingdom. If it was, it would be the first work to be banned in such a kingdom. The fate of Socrates in Athens, of poets in Plato’s Republic, of visionaries in Augustine’s City of God, and (of course) of Jesus in Jerusalem, shows that there is no room for the unfettered imagination in the Heavenly City, because its limits always go beyond what is, towards what might be: beyond what is prescribed, towards what is possible; beyond what is allowed, towards what can be imagined.

When we set aside theology and history, we find ourselves looking at the Bible as a structure of the imagination, and viewing it through the lens of the imagination. It is striking that all serious religions have a close and continuing association with the human products of culture that we call art: the statues and stupas of Buddhism, the mosques and minarets of Islam, the cathedrals and the church music of Christianity, the poetry of the Psalms. E.M. Forster rightly remarks in Aspects of the Novel that ‘great art is like great religion: it forces you out into the world on its service’: the community of the imagination is not a closed community of belief but an open community of vision. When Donne proclaims that ‘no man is an island, entire of itself … any man’s death diminishes me’, the truth of the statement is immaterial. It is a call to live, and to act, as if it was true.

When we read it in this way, the world imagined in the Bible is not so much discovered as rediscovered. Wordsworth’s instinct that ‘The Soul that rises with us, our life’s Star/Hath had elsewhere its setting,/And cometh from afar’, and his glimpse of ‘the vision splendid’ that attends the youth but ‘fades into the light of common day’; Baudelaire’s ‘Les vrais paradis sont les paradis qu’on a perdus’ and ‘Le génie, c’est l’enfance retrouvée’e – these spring from the same sense of a world that we come from – and long to return to. The core myth of the Bible is deliverance, and its core metaphors are the city and the garden: deliverance is not just deliverance from, but deliverance to, and it is to the transformed and renewed Garden of Eden and City of God, symbols of our true home, that the Bible longs to return, to ‘arrive where we started’ and ‘know the place for the first time’.

Just as place is rediscovered, so is time. When after long wandering in the wilderness the weary reader reaches Le Temps Retrouvé (Time Rediscovered), the final volume of Proust’s mighty work, he finds that along with the promised rediscovery of time there is a rediscovery of self and of human grandeur: we realise that the quirky and fallible characters of his story are ‘giants in time’, and that the time in which they are giants is the timeless world of eternity, time rediscovered and reinterpreted, not the endlessly repeated time of the fallen world. And just as time and place are revealed in this imagined world, so too is our acquaintance with a different vision of God: not Blake’s ‘Accuser who is the God of this world’, but the ‘abba’ that Jesus speaks to, the God who learns, who changes his mind, who allows himself to be persuaded (Genesis 2:19, 8:21, 18), who gently and ironically celebrates his own inconsistency (Jonah 4:11), and who watches over the fall of a sparrow (Matthew 10:29). This is not a world of an inflexible and intimidating perfection, but one in which we can say with Wallace Stevens that ‘the imperfect [the unfinished, the not-yet-complete] is our Paradise’.

Milton saw the Bible with its recurring upward movement as ‘a manifesto of human freedom’.62 What gets in the way of freedom, and appears when seen through a theological filter as sin, becomes in the language of the visionary imagination a fear of freedom, the feeling that Sartre characterised as an effort to flee from the ‘pour soi’ to the ‘en soi’,f to pretend that we are the prisoners of our past rather than the makers

Footnotes

a. In Leviticus 14:4–7 and 49–53, we find the same pattern: to heal the community from leprosy, the priest takes two birds, kills one, and releases the other after dipping it in the blood. We remember the crowds in Matthew 27:25 crying, ‘His blood be on us …’.

b. We might also point out the parallelism in birth between Moses, the Old Testament hero, and Jesus, the hero of the New Testament: Jesus is placed in a manger and provided with a kind of dual parentage – God and Joseph – reflecting the way that Moses is placed in an ark of bulrushes, and brought up both by his humble birth mother and by the daughter of Pharaoh (Exodus Chapter 2). The Old Testament Law is given on Mount Sinai; it is not an accident that the sermon giving the new law, the revised contract between God and man, is also given on a mount. The repeated food miracles in the New Testament, feeding Israelites in the wilderness with loaves and fishes, reflect the miraculous feeding of the Israelites with manna in Exodus; Jesus’ death, descent, and resurrection echo respectively the Angel of Death at the Passover in Egypt, the Israelites’ crossing of the Red Sea, and their escape into freedom. Moses dies on the verge of the Promised Land and it is Joshua who brings the exiles home to their inheritance: in the same way, according to the New Testament writers, the Law of Moses fails on the edge of salvation, and it is left to the child Jesus (Jesus and Joshua are the same name) to establish the New Testament and accomplish the task.

c. The commandments about killing and adultery, for example, are not the absolute prohibitions that they may seem. The prohibition on killing did not apply to war, to capital punishment, or to non-Israelites, as the Old Testament abundantly demonstrates. And the prohibition on adultery does not apply to men. It is aimed at the sexual conduct of a married or betrothed woman, the point being, not the preservation of chastity, but the protection of the husband’s lineage against the risk that he might raise a child not his own, a cuckoo in his nest.

d. The Geneva Bible of 1560, product of a radical Protestantism, frequently glosses ‘king’ as ‘tyrant’. The more cautious Authorised Version of 1611, commissioned and approved by King James, never once uses this term (Alister McGrath, In the Beginning: The Story of the King James Bible, 2001, p. 143).

e. ‘The real paradises are the paradises one has lost’; ‘Genius is childhood rediscovered’.

f. A thing or an animal is ‘en soi’ (‘in itself’), without free will. A human, in Sartre’s view, is ‘pour soi’ (‘for itself’), having no fixed identity, and so having to choose who to be. Sartre saw people as trying to get rid of this frightening freedom by pretending to have a fixed personality (a soldier, a waiter, an anti-Semite), in other words to be ‘en soi’ rather than ‘pour soi’. of our own future. Freedom that restores to us our own creative powers, that reminds us that we have created the gods to which we bow down, is hard work and requires discipline and a readiness to accept the responsibility that it brings for our own actions and their consequences. The Bible has been made into an instrument of divine tyranny, but like all great powers of culture, it is a work of the human imagination, and artists have always recognised that. Properly understood it celebrates our recapture of our own imaginings. Its message is the appeal of Tennyson’s ageing but vigorous Ulysses to his faithful crew: ‘Come, my friends/’Tis not too late to seek a newer world …’