The Tenth Commandment //

Be Brave

It all comes down to this: be brave. That’s what this entire book is about, after all. Ten steps to brand bravery. Ten strategies to incite bold decision-making and convention-challenging work. Ten reminders to serve customers in the smartest way possible, even if those methods have never been tried before.

But what is bravery? Often it’s a catch-all term with a definition that is contextually defined. For one person, bravery might mean getting on a plane. For someone else, it’s sitting still while a wasp buzzes around their picnic table. For some, it might mean crying.

Bravery is, in large part, undefined. It’s variable. And that’s exactly why it’s perhaps the most relevant commandment for every single business in the world. No matter what bravery specifically means to your company and its clients and customers at this moment in time, we firmly believe that you must do it, or else be lost in the slipstream. Bold action and courageous ideas give consumers a reason to believe and enable brands to stand out from the pack.

Great ideas have never been more essential and yet have never been harder to put into action. Budget cutters, short-termism and our own fears and biases threaten the one thing proven to deliver effective marketing: creativity. But risk-aversion isn’t just putting pressure on marketing. It is an anti-creative juggernaut careening down the highway, with entire businesses caught in the headlights.

Truly creative ideas are rarely predictable. They’re often difficult to keep on deadline and under budget. Writing in The Armed Forces Comptroller, management expert Lynne C. Vincent writes, ‘Creativity is inherently risky. A creative idea by definition is novel and useful. If the idea is truly novel, it will have some risk attached … Because of this risk, people often feel more comfortable maintaining the status quo.’

At Contagious, we’re allergic to the status quo. We believe that brave, innovative creativity is the best means to gain an unfair advantage over the competition. Ideas are democratic, after all, and even the biggest brands must continually earn consumers’ trust and respect. All other things being equal, the braver brand will make more creative work and will win in the long run. This has particularly been proven true in the world Contagious concentrates on: marketing. Simply put, we hold that creative work kicks the shit out of non-creative work when it comes to selling stuff. And plenty of people have confirmed that hypothesis for us already.

WE’RE NOT MAKING THIS UP

Perhaps best known among the research into the link between creativity and effectiveness is a study by Les Binet and Peter Field of the UK’s Institute of Practitioners in Advertising (IPA) titled, er, The Link Between Creativity and Effectiveness. Binet and Field analysed 1,000 case studies in the IPA effectiveness database and found that creatively awarded campaigns were eleven times more efficient than non-creatively awarded campaigns from 2000 to 2011, when standardized for excess share of voice (how much of the conversation a brand owns versus its competitors, accounting for share of market). Creative ads resulted in a 2.34 per cent growth in market share versus a 0.2 per cent growth for non-creative ads. From 2011 to 2016 the effectiveness multiplier for creative vs non-creative work dropped from eleven to six, largely due to an increasing focus on short-term results. (Remember the emphasis on agile long-termism in the first commandment?)

In another study, titled The Long and the Short of It, Binet and Field point the finger directly at the thirst for short-term results tracking in the digital era: ‘Even more worrying is the drive to develop real-time campaign management systems driven by these short-term response metrics: unless such systems are heavily counter-balanced by long-term metrics and activity, they could prove to be a death-sentence for brands.’

Other researchers have looked at the value of creativity in spurring advertising effectiveness. In his long-running study ‘Do Award-Winning Commercials Sell?’, Donald Gunn, the worldwide director of creative resources at Leo Burnett, found that creatively awarded television ads resulted in 5.7 per cent growth in market share per 10 per cent excess share of voice. Non-creative ads, against that same media spend, resulted in growth of just 0.5 per cent.

In the Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science in 2014, Jiemiao Chen, Xiaojing Yang, and Robert E. Smith published research that showed that the effects of creative work also last longer than the effects of non-creative work, as consumers are less likely to get tired of the message. ‘When an ad has both divergence and relevance, it resists wearing-out even at high levels of repetition,’ they write, citing their definition of creativity (divergent yet relevant). ‘Only creative ads were able to resist wearing out at high exposure levels. Thus, the positive effects of creative ads are more pronounced over multiple repetitions.’ So you can go ahead and add ‘cost savings’ to the list of creativity’s benefits. The longer your ads last before diminishing in impact, the fewer ads you need to make.

Finally, creativity has been shown to result in bottom-line success for companies brave enough to commit to it. In the 2016 edition of his book The Case for Creativity, James Hurman notes that companies that win the title of Cannes Creative Marketer of the Year outperform the S&P 500 by a factor of 3.5, with annual share price growth of 26.1 per cent vs 7.5 per cent on the S&P from 1999 to 2015. ‘Effectiveness is most efficiently driven by campaigns that create fame,’ he writes. ‘Fame is most efficiently achieved with creativity.’

Without a doubt, our goal as marketers and brand builders should be to get the most creative work possible. So what’s stopping us?

POISON, VOMIT, AGONY

Unfortunately, we are what’s stopping us. Human brains aren’t wired to embrace the uncertainty of creativity. We’re wired for consistency, predictability, and minimizing risks. We say we want creativity, but when confronted with actual fresh ideas, our brains rebel against us.

In 2010 researchers Jennifer S. Mueller, Shimul Melwani, and Jack A. Goncalo published a paper through Cornell University’s ILR School called ‘The Bias Against Creativity: Why People Desire But Reject Creative Ideas’. It confirmed our brains’ unwillingness to embrace creativity, even when we say we’re open to it. ‘People often reject creative ideas even when espousing creativity as a desired goal. The results demonstrated a negative bias toward creativity when participants experienced uncertainty. Furthermore, the bias against creativity interfered with participants’ ability to recognize a creative idea,’ they wrote.

The researchers put study participants into two mindsets, high tolerance for uncertainty and low tolerance for uncertainty, by instructing them to write an essay supporting the statement: ‘for every problem, there is more than one correct solution’ (high tolerance for uncertainty) or ‘for every problem, there is only one correct solution’ (low tolerance for uncertainty). They then used what’s called an ‘Implicit Association Test’ (IAT) which instructs people to press keys on a keyboard in response to specific terms and then measures their reaction times. Using four sets of categorized words (positive, negative, creative, and practical), the IAT tested participants’ subconscious linkages between the different feelings. They found that participants in the low tolerance for uncertainty group associated creative words with the negative batch – words like poison, vomit, and agony. When asked to rate a creative idea, the same low-tolerance group rated it as less creative than their more-tolerant compatriots.

‘Our results suggest that if people have difficulty gaining acceptance for creative ideas especially when more practical and unoriginal options are readily available, the field of creativity may need to shift its current focus from identifying how to generate more creative ideas to identifying how to help innovative institutions recognize and accept creativity,’ wrote the authors. That is to say, we don’t need to focus on coming up with more creative ideas. We’ve got that part under control. Instead, we need to work on recognizing and nurturing those ideas to make them into reality.

Everyone knows the Christmas holidays are no time for selfishness. The soft-focus ads that dominate television toward the end of the calendar year hammer that point home, chock full of warm fuzzies, random acts of kindness, and gushing generosity. To do anything else would be risky. It would also be brilliant. In 2013 British metropolitan retailer Harvey Nichols took that risk, breaking from seasonal norms and risking a customer backlash to an anti-generosity campaign at the most selfless time of the year. The Sorry I Spent It On Myself campaign featured ads showing gift-buyers giving mundane items like rubber bands and paper clips to their loved ones, while happily holding on to a costly new purchase they’d made for themselves with the leftover cash. The retailer took the campaign one step further as well, creating a real line of the same ‘Ultra Low Net Worth’ items featured in the spots. Within a single day of going on sale, the range of products sold out.

The campaign zagged while everyone else zigged, and stuck out as a result. With its cheeky tone and excellent craft, Sorry I Spent It On Myself took home four Grand Prix awards at the Cannes Lions Festival of Creativity. But it was far from accidental. ‘A lot of the comments at Cannes were about how it was so brave to fly in the face of Christmas,’ says Richard Brim, an ECD at adam&eveDDB who worked on the campaign. ‘That’s how we’ve behaved with Harvey Nichols all along; we just pushed it to the nth degree.’

Indeed, Harvey Nichols (which has an organizing principle of ‘Fearlessly Stylish’) hasn’t shied away from bravely creative campaigns in recent years. In 2015 it launched a mobile-first refresh of its loyalty programme with a campaign consisting of security camera footage of real shoplifters in Harvey Nichols stores, superimposed with cartoon faces. ‘Love freebies?’ the strapline asked. ‘Get them legally. Rewards by Harvey Nichols.’ Another winter campaign saluted the ‘walk of shame’ with people leaving one-night stands in their going out clothes. And the brand’s 2015 Christmas advert showcased the ‘Gift Face’ put on by people who have just received a less-than-desirable gift, another shot across the bow at the Spread Christmas Cheer establishment. ‘There’s a playfulness to Harvey Nichols when you put it against all the other retailers who, at that time of year, are incredibly schmaltzy,’ Jessica Lovell, a planner at adam&eveDDB, told Contagious. Swimming against the current breaks through the clutter of a crowded advertising period, and it takes some chutzpah to do it.

RECOGNIZING AND ACCEPTING CREATIVITY

Most companies are wired the same exact way as those study participants. They’re wired for consistency, predictability, and minimizing risks. When presented with both a practical solution and a creative one, the majority will take the practical to market and save the creative idea for a rainy day. And they do this while talking about creativity as an important part of their business. It’s a difficult talk to walk.

There’s an inherent contradiction in how businesses tend to be run. Senior leaders are expected to approve bold creative ideas that have the potential for exponential impact, but at the same time are pressured to meet deadlines, stay within budgets, and keep the company away from risks. We reward and motivate people based on certainty and dependability. Instead, marketers should force themselves to push past their instinct to cling to safety. Progress requires growth, and as the old maxim goes, without change there is no growth.

Being brave does not mean being foolhardy, though. Aristotle, that famous brand strategist, cited Courage as one of the four cardinal virtues back in the fourth century BCE, but noted that too much could lead to recklessness. ‘The courageous man withstands and fears those things which it is necessary and on account of the right reason, and how and when it is necessary,’ he wrote (though we’re relying on others to translate the ancient Greek for us, so best to treat it as a paraphrase). Be brave, but in moderation. Companies must have a systematic approach to achieving creative ideas in a way that tolerates, but minimizes, risk.

At Contagious, a cornerstone of our business is helping clients hone this approach. To recognize, accept, and encourage creativity, while constructing guardrails that prevent wasted effort and unnecessary risk. We strive to turn accidental (or against-all-odds) creativity into a deliberate practice of creative excellence. We encourage our clients to take a well-informed step into the unknown, away from what has worked thus far if necessary. We inspire them to follow convictions into uncharted waters. We tell them not to anticipate failure, but not to fear it either.

As poet Robert Frost once wrote, ‘Freedom lies in being bold.’

BRAVE WORKS

We’ve spilled lots of ink in this book (and a few extra drops in the boxed sections of this commandment) citing examples of work that could be considered brave. In most of those cases, the brands were emboldened to be courageous because they adhered to the commandments. Patagonia was brave to tell people not to buy its jacket, but was emboldened because of its crystal-clear organizing principle. It was brave of Kenco to invest its marketing budget in moving at-risk Honduran youths from gang-filled areas to coffee plantations, but it followed through on the idea because of a mindset that prioritized generosity. Art Series Hotels’ bold decision to give away hotel rooms for free was empowered by asking intriguing, heretical questions about its fundamental business model.

Every creative campaign in this book was the result of brave decision-making on the part of people inside agencies and clients, working together to push for something better than the status quo.

But all of those examples – and all of the commandments you’ve read thus far – don’t amount to much if they’re not put into action, with bravery and conviction. Marketing, after all, isn’t an entirely theoretical exercise. While you’re at the office reading the latest research, your advertising is out on the town, carousing and trying to snag a date. To make these ideas work, companies need to build a culture where creativity is safeguarded and bravery becomes a working practice. Sure, brands with a maverick creative flag flyer may be able to sneak through some moments of creative brilliance. But we want you to champion, or to systematize, creativity as an entire organization. And to do so, you’re going to need a few tools.

A CREATIVE LEXICON

The first arrow in your bravery quiver (there’s an oxymoron for you) is a common language. Too often, creativity is mired in the fluffy talk of inspirational lightning strikes and flashes of brilliance in the shower. Creative ideas, legend has it, come from putting creative people in a room and letting them ‘noodle on it’ for a few days (and, often, a few drinks). This takes creativity out of the hands of the masses, creating two classes – the creatives and the create nots. We firmly disagree. Creativity is a muscle, to be exercised and strengthened through challenge and repetition. Sure, some people have a natural knack for it, just as some people are naturally more athletic or more musically inclined. But even the most astringently left-brained among us can be taught to be creative, or at the very least to become open to the idea of creativity and persevere against our unconscious biases.

To help move the creative conversation from qualitative and subjective to quantitative and objective, we need a common language that allows us to communicate, rationally and with a shared purpose.

During his tenure at Leo Burnett, Paul was a member of the network’s Global Product Committee, which evaluated creative campaigns against an acclaimed 1–10 system known as the 7+ Scale. Contagious first put a similar idea to work with global brewer Heineken in 2015, via an advisory project aimed at scaling great creativity throughout the organization. Together with the Global Commerce University (Heineken’s internal training and development unit), we devised the Creative Ladder, an assessment tool ranging from 1 (destructive) to 10 (world-changing) designed to help everyone within the organization put words against subjective feelings. Beyond the top-level descriptors, each rung of the ladder has a detailed explanation of what work fits under what rating, applying clear evaluative language to move from qualitative to quantitative conversations.

Rather than saying ‘I don’t like this’ or ‘I think this is fine’, marketers inside Heineken were enabled to quantify their feelings – ‘I think this is a 5 (ownable), because it uses unique executional cues to rise above a cliché’ or ‘I think this is a 7 (ground-breaking), because it provokes a change in the perception of the category.’ The term ‘ladder’ was deliberately chosen; it’s impossible for an idea to score a 7 without being built on the foundations of an ‘ownable’ idea, executed in a ‘fresh’ (rung 6) creative manner. One of the main drivers was to avoid deploying advertising that scored a 4 (cliché), and would therefore be uncompetitive in the category.

‘If you want great creativity you need to be able to talk about it and to give it a language, because more often than not, creativity is very subjective, it has a lot to do with gut feelings, and the experience and legacy of the different individuals,’ Cinzia Morelli-Verhoog, then Heineken’s senior director of global marketing capability, told Fast Company in 2015. ‘By introducing the creative ladder we created a language within Heineken.’

In the same interview, Morelli-Verhoog observed that it’s riskier to play it safe, because safe marketing blends in and is ignored. ‘The biggest risk in this case is if Heineken were an organization that sees anything that has not been done before as risky,’ she said. ‘Actually, for us, the creative that is most risky is clichéd because you know for sure it will not make an impact and be part of the wallpaper, where we don’t want to be.’

Arif Haq, who led the Contagious creative capabilities practice at the time and worked with Heineken to develop the ladder, comments:

The hardest task in this industry falls not to the individuals whose job it is to come up with brave new ideas, but to the clients who risk their jobs in approving them. I’m not sure why we ever thought it was a smart idea for people with no formal creative training to be able to provide expert feedback on creative ideas, and yet that’s exactly what we expect of brand managers on a regular basis.

Many assume the ladder’s power lies in the scoring numbers. But its real value is in the language, not only in the titles of each rung, but the accompanying descriptions which explain in detail why, for example, a 7 is a 7 and not a 6 or an 8 (contagious). It’s essentially a dictionary of creative language designed for brand managers to articulate advanced creative ideas to their bosses, and also their agencies, peers and, critically, themselves.

The ladder is a tool that helps to transform the corporate perception of creativity from an accidental, ‘magical’, and therefore risky idea to something that can be predicted and replicated, thereby allowing it to be scaled.

Yuval Harari, in his book Sapiens, which tracks the evolution and eventual domination of humans on earth, ascribes our success as a species to the ability to communicate quickly and clearly – essentially scaling through language. ‘How did we manage to settle so rapidly in so many distant and ecologically different habitats?’ he writes. ‘The most likely answer is the very thing that makes the debate possible: Homo sapiens conquered the world thanks above all to its unique language.’ In a similar way, language enables us to unpack the complexity of creativity and make it accessible for people with different skills in different jobs in different areas of an organization.

Much of this conversation about creative lexicons stems back to the ideas above about why we reject creativity. When we have trouble fully grasping an issue or an idea, it is easier to say no than to understand whether we should or shouldn’t follow it to its potentially impactful conclusion. Remember that talk of objective disqualifiers in the third commandment? Creative discussions are full of subjective disqualifiers. Feedback like ‘I don’t get it’ and ‘I don’t like it’ – or, worse still, ‘the client/audience won’t like it’ – are mired in subjectivity – whoever is highest on the org chart or shouts the loudest in the meetings gets final say. A common lexicon around creativity moves subjective disqualifiers into the realm of objectivity, where it is easier to pinpoint actual issues with work – and then hopefully move on to figuring out ways to make it better.

CREATE ADVOCATES TO ADVOCATE CREATIVE

Our work with Heineken, and the other clients with whom we’ve shaped creative excellence guides and curricula, goes beyond simply crafting a list of ten grades and calling it a day. In addition to building the lexicon, organizations must promote these new languages, and teach people how to use them constructively. It needs to become habit. For Heineken, this meant a series of local and regional creativity masterclasses to educate marketers on the ground and to embed the language of the ladder into practical conversations, and the founding of a creative council of senior leaders to review and judge the company’s creative output.

At Contagious we advise our clients to select internal advocates tasked with leading the charge for creativity both at the senior level and throughout the organization. We help to build creative councils, which routinely review work to see how the brand’s work, both internally and outside its walls, stacks up against an objective scale. We develop continuing education programmes, to help marketers understand the evolving challenges in the marketplace, as well as hone their skills as brave advocates for ideas that will break through.

At its core, bravery is a struggle between mind and matter. If you have a fear of bees or heights or clowns, you might call it an ‘irrational’ fear. Your mind tells you there’s nothing to be afraid of, but you break into a cold sweat whenever you’re in a phobia-inducing position. Having language in these scenarios – logical, rational language that can deconstruct a situation – is a powerful tool. And when fighting for brave creativity, it can sometimes be the only tool that works.

Picture an ad for a feminine hygiene product like a tampon or pad. Now let us take a guess at one of the key components. Is there a mystery blue liquid involved? It’s an entrenched cliché that has come to define the category’s comms themselves. Rather than show blood, ads opt for a generic replacement liquid. It’s a rule no brand dared to break. Until Bodyform came along, at least. In 2012 the brand (which is owned by Swedish health and hygiene firm Essity) released an ad called The Truth, in which an actress playing CEO Caroline Williams reveals the truth about periods to a male Facebook commenter. ‘I’m sorry to be the one to tell you this, but there’s no such thing as a happy period,’ she said, citing ‘the cramps, the mood swings, the insatiable hunger, and yes Richard, the blood coursing from our uteri like a crimson landslide’. Rubber Republic, the agency behind the work, reports that the video received 6 million views, nearly entirely through earned media, and increased Bodyform search traffic by 1,000 per cent.

In 2016 the brand built on that success with a series of three campaigns across Europe that sought to destigmatize periods and break category norms with bold messaging. After polling 10,000 men and women in ten countries, the brand found that a third of people had never seen a woman openly discuss her period in film, television, or books. ‘We’re more likely to see blood in scenes of horror in popular culture than we are to see something as normal as a woman talking about her period,’ Essity global brand manager Martina Poulopati told Contagious. The campaigns, aimed at women between eighteen and thirty-five, talked openly about how periods affect women’s health and energy levels, addressed cultural taboos about buying feminine hygiene products, and – most critically – swapped out the blue liquid for a more realistic red.

The third spot, called Blood Normal, generated 796 million PR impressions, 80 million social impressions, and 6 million video views within three weeks. The longer-running campaign, called Red.Fit, achieved 90 per cent of its reach through earned media, and resulted in improvement across all brand equity pillars measured by Essity – both functional and emotional – as well as increased product trial levels.

‘Working in feminine care, one of the first things you realize is how many taboos are in this category and that most of the brands follow these norms. Bodyform was brave enough to be the first to break from that and from the huge response it was clear that there was something there for the brand,’ says Poulopati.

KNOW THE BARRIERS TO CREATIVE WORK

Next time you’re bored at work, do an experiment: ask any of your industry friends if they feel like they are empowered to take wildly creative risks in their day-to-day jobs. Unless you’re friends with the luckiest people in the world, almost all of them will say, ‘Well, not exactly.’ When you ask them why, familiar themes will start to emerge. They are too busy managing people or projects to have time to think. They have to hit budgets and deadlines. They can’t afford to fail. When they’ve pushed for out-of-the-box creative in the past, someone in the C-suite has shut it down. They might get laughed at.

Then, ask the same question inside your own company. What is the biggest barrier to creativity in your organization? Is it knowledge? Time? Encouragement? Resistance to change? Focus on the short term at the expense of the long term? Knowing where your creativity gets bottlenecked is the first step to confronting that issue.

By addressing those bottlenecks, companies can create a culture that thrives on new ideas and encourages people to take the time to find them. Maybe it’s a leader giving an award for failures, to show that great ideas often rise from the ashes of aborted attempts. Maybe it’s setting aside time for experimentation. Or maybe it’s something as simple as encouraging people to ask questions and share off-the-wall ideas in judgement-free sessions.

Because, ideally, creative bravery isn’t brave at all. It’s smart, fresh, and as risk-insulated as you can possibly make it. It’s good business practice. As Phil Adams, strategy director at agency Cello Signal, wrote in a 2017 article for The Drum, ‘I have worked with clients who didn’t need the crutch of pre-testing research in order to approve an idea. And I have worked with a few who have ignored negative research feedback to press ahead with advertising that they believed in. I wouldn’t describe these people as brave. I’d say that they knew what they were doing. Good ideas aren’t dangerous or risky, they are disproportionately effective.’

In practice, the ecosystem trends more toward the old axiom that ‘no one ever got fired for buying IBM’. Even if we know in our hearts that creative ideas win out, our minds seek ways to not rock the boat. To keep the ship afloat until it’s time to retire. To focus on the quotidian minutiae rather than confronting the big scary challenges looming on the horizon. But this is a fast track to a slow decline. As Dwight Eisenhower once said, ‘What is important is seldom urgent and what is urgent is seldom important.’

HIRE (AND MANAGE) FOR BRAVERY

Bravery cannot be the domain of a single person in an organization. It cannot be a departmental pursuit. Yes, a specific person or persons or department may lead the charge. And companies with a single creative catalyst may occasionally find a needle in a haystack. But repeatable brave creativity requires an environment designed to foster it. And that (surprise!) also requires moving away from the all-too-status-quo. As usual, it requires being slightly uncomfortable.

‘The worst kind of group for an organization that wants to be innovative and creative is one in which everyone is alike and gets along too well,’ wrote team performance expert Margaret Ann Neale, the Addams Distinguished Professor of Management at Stanford University, in 2006.

Organizational behaviour expert Barry Staw, in an essay titled ‘Why No One Really Wants Creativity’, echoes that idea. ‘From what we know about organizations, they work very hard to recruit and select employees who look and act like those already in the firm. For those who might have slipped into the organization without the proper skills and values, socialization is usually the answer,’ he writes. ‘Creating clones of existing personnel is generally what management wants and gets.’

These homogeneous cultures do not lead to great ideas. They lead to organizational blinkers that leave companies open to fading into obscurity at best and creating destructive work or being disrupted at worst. Homogeneous groups lead to homogeneous ideas.

Recent research from McKinsey shows that companies in the top quartile of gender diversity are 15 per cent more likely to have financial results above their industry medians. What’s more, companies in the top quartile for racial and ethnic diversity are 35 per cent more likely to have financial results above their industry medians. And every little bit counts. Writes McKinsey London director Vivian Hunt: ‘In the United States, there is a linear relationship between racial and ethnic diversity and better financial performance: for every 10 per cent increase in racial and ethnic diversity on the senior-executive team, earnings before interest and taxes rise 0.8 per cent.’ These are incredible numbers, and proof that inviting different people into conversations pays dividends in the form of well-rounded companies that can produce sharp ideas.

Beyond just hiring those people, organizations must strive to empower them to make bold decisions without penalty – assuming the risks they entail are measured and minimized as far as reasonably possible. As General George S. Patton said, ‘Don’t tell people how to do things. Tell them what to do and let them surprise you with the results.’

It’s an idea echoed by Teresa Amabile in her 1998 Harvard Business Review essay ‘How To Kill Creativity’:

Autonomy around process fosters creativity because giving people freedom in how they approach their work heightens their intrinsic motivation and sense of ownership. Freedom about process also allows people to approach problems in ways that make the most of their expertise and their creative-thinking skills. The task may end up being a stretch for them, but they can use their strengths to meet the challenge.

You’ll recall the conversation about adaptive versus tactical thinking from the first commandment; a similar principle applies here. Give people the space to be creative, and chances are they will take you up on that offer.

Not many brands have an in-house mischief department. But then again, not many brands are like Irish bookmaker Paddy Power. The gambling company has offered odds on the next pope being black, faked cutting down a Brazilian rainforest, and sponsored an egg-and-spoon race in the French town of London so it could bill itself as the ‘Official sponsor of the largest athletics event in London this year’ during the 2012 Olympics. Leprechaun-like mischief is a part of the company’s DNA.

‘It’s important to understand that we are the underdog in this industry,’ Paul Sweeney, head of brand at Paddy Power, told Contagious in 2014. ‘We are outspent four-to-one by some of our traditional competitors, so every pound we spend must go four times further.’ The aforementioned in-house mischief department has worked closely with agencies like Crispin, Porter + Bogusky, Lucky Generals, Chime Sports Marketing and WCRS (as well as the Paddy Power legal department) to craft big box-office stunts that keep the brand in the news. ‘The one rule is that we can’t risk anyone in the company going to jail,’ says Sweeney. ‘Apart from that, it’s fair game.’ The offline stunts are supported by a sophisticated online editorial team tasked with listening to what gamblers are saying and creating relevant content that cuts through and connects on an emotional level.

Led by this underdog sense of necessary bravery, Paddy Power has made headlines – and a dent in the competition. In 2014 the brand wrapped up a decade of 30 per cent year-on-year growth, with 49 per cent of their bets taking place via mobile, far above the 9 per cent average in the industry. It’s a symptom of smart thinking and bold action following through on the words of the brand’s first CEO, Stewart Kenny: ‘We’re going to take your money, so we’ll make damn sure you have fun while we do.’

INTRINSIC AND EXTRINSIC MOTIVATIONS

You can lead a horse to water but you can’t make it drink, or so the saying goes. What if you hire a horse in a creativity-conducive environment? Can you make it be creative?

Equines aside, companies attempting to spark creativity often come up against this nature vs nurture type discussion. Can you build a creative culture that truly encourages employees to make brave decisions and develop creative ideas? Or is it simply a question of hiring ‘rockstars’ who have creativity coursing through their bloodstreams?

In reality, two sets of motivating factors drive us to complete any task: intrinsic motivations and extrinsic motivations. Intrinsic drivers come from within a task, and motivate people to do something for the sheer sake of doing it. Full stop. We go for a run because we want to go for a run. In a job setting, intrinsic motivators have been described by St John’s University assistant professor Rajesh Singh as ‘psychological feelings that employees get from doing meaningful work and performing it well’.

Extrinsic motivations, on the other hand, happen outside the task itself. Think: promotions, financial rewards, prizes.

We often think of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations as happening inside or outside the individual – either someone is a ‘self-starter’ or they’re working for the weekend. And research is divided as to whether extrinsic forces alone can actually motivate employees to create good work regularly. As we discussed in the first commandment, ‘making a profit’ is not a sufficient organizing principle to drive a company forward.

Recent research, however, suggests that extrinsic and intrinsic motivations may be more closely linked than previously thought. ‘Mechanisms Underlying Creative Performance’, a study by Hye Jung Yoon, Sun Young Sung, and Jin Nam Choi published in the journal Social Behavior and Personality in 2015, found that when it comes to creativity, extrinsic rewards (assuming the reward is something valued by the employee) influence attitudes toward a task and consequently inspire more creative work:

In the case of extrinsic rewards for creativity, although rewards of this type did not have a significant direct effect on creative performance, extrinsic rewards were significantly related to commitment to creativity, which, in turn, had a meaningful effect on creative performance. Our results showed that extrinsic rewards had a significant indirect effect on creative performance via commitment to creativity, suggesting that the intermediate psychological condition is critical for extrinsic rewards to influence creativity.

So what does this mean? If you can, hire people with an intrinsic drive to be creative and develop brave ideas. Then, incentivize them to do just that, with something they’ll actually value. And finally, turn them loose on a task. As Erik Sollenberg, the former CEO of stellar Swedish agency Forsman & Bodenfors, said of his employees: ‘The only boss they have is the task itself.’ The agency has a list of principles it enforces as employees work on those tasks:

// Show your colleague what you’re working on.

// Listen to their critique.

// Learn.

// Be prepared to change your mind.

// Share your success.

// Engage in other people’s work and give your opinion.

We don’t claim to be psychologists or behavioural scientists, but these principles seem to blur the line between intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, creating an environment where employees are driven by the task at hand and extrinsically rewarded through opportunities to fulfil their intrinsic drive. As in one example Sollenberg cited: ‘One of the copywriters on [two high-profile projects] is a newly hired quite young creative. In order to do that type of work in a traditional agency you would probably have to wait quite a few years.’ The extrinsic reward, in this case, is the ability to work on high-profile campaigns, which spurs intrinsic drive and results in exemplary creativity.

BRIEF FOR BRAVERY

Perhaps the worst-utilized implement in the marketer’s toolkit for cultivating a creativity-inducing environment is the brief. For readers unfamiliar with the advertising world, think of the brief as marching orders for developing a campaign, typically given to an agency by a brand client, laying out their key objectives. When Contagious conducted a survey among some of the industry’s leading creatives about the briefing process in 2017, we heard it time and time again. ‘The worst thing is when people give you a brief with an outcome they’ve already got in their head and they don’t want you to deviate off that path and become irritated if you do,’ Nick Worthington, creative chairman at Colenso BBDO in New Zealand told us. ‘They’re limiting the opportunity to do something extraordinary.’

When talking about bravery and creativity in the context of advertising, it is impossible to ignore this delicate dance between agency and client. The briefing process is an opportunity for a brand to establish its thirst for bravery, while defining the parameters and measurable objectives for a campaign.

‘You do your best work when people ask you to do your best work,’ Andy Nairn, founding partner of agency Lucky Generals, told us. ‘Clients can frame the brief and make it stand out by saying that they want something brilliant. I know that sounds like stating the obvious, but some of the time you don’t get that impression. Some of the time you get the impression that people just want something OK, that will continue and evolve what they’ve already been doing.’

‘To get contagious work, the briefs are just the beginning, and making that work come alive is something completely different,’ says Worthington. ‘Pretty much anyone can have a brilliant idea, and they often do, but very, very few people are capable of executing those ideas brilliantly.’

The fact of the matter is that agencies will, most of the time, follow the brief they are given. Occasionally they’ll break away and create something off-the-asked-for-path, but even in those cases it’s rare for the client to agree to go along with them. Jim Carroll, former chairman at BBH UK, put it this way: ‘Extraordinary work often correlates less directly with the brief, breaks conventions and uses unfamiliar reference points … Extraordinary work is ordinarily very easy to reject. In nearly all aspects of business, intelligence represents a competitive advantage. But in the judgement of creativity it can represent a curse, a competitive disadvantage.’

And when clients buy ordinary work, they get ordinary work. They send a message to their agency that they’re not interested in truly creative ideas. Consequently, talented creatives at those agencies choose to work on different accounts. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy: unless you’re asking for great work, you won’t get it.

As Marc Pritchard, global marketing and brand-building officer at the world’s largest advertisers, Procter & Gamble, said at the Cannes Lions Festival in 2012: ‘I like to tell people you need to inspire creative work that is so brilliant you’re willing to bet your career on it.’

‘This is all or nothing. This is death or glory. This is one giant gamble to turn the beer scene on its head.’ So stated Scottish brewery BrewDog in February of 2018, when it announced it would be giving away 1 million free pints in its branded taprooms. The brewery, whose founders once famously proclaimed that they would rather light their money on fire than buy traditional advertising, paradoxically used posters created by London agency Isobel to dare consumers: ‘Don’t buy the advertising. Make up your own mind.’

BrewDog has always been a rebellious brand – the word punk adorns almost all of its messaging, including its flagship Punk IPA and its ‘Equity For Punks’ crowdfunding campaigns. It even described itself as a ‘post-punk, apocalyptic, motherfu*ker of a craft brewery’ before the UK’s Advertising Standards Authority rapped its knuckles. And its messaging has certainly lived up to that counterculture ethos. The brewer has three times brewed the strongest beer in the world (most recently in 2010, with a 55 per cent ABV IPA called ‘End of History’ served in bottles inside taxidermied squirrels and stoats), has distributed free posters for fans to illegally ‘fly post’ all over the UK, posted all of its own recipes online, and even released a beer laced with steroids to mock competitor Heineken’s sponsorship of the 2012 Olympics. A crazy streak runs through its DNA.

‘The fact is, big brands say no to that kind of thing because they see perceived risks, but actually the opportunity of taking a stand far outweighs any risk. Because it’s true to a purpose, people can disagree, but we can’t be wrong,’ Alex Myers, founder of long-time BrewDog PR agency Manifest, told Contagious. Within the brand, marketers ask themselves if any other brand could produce a campaign they’re considering. If the answer is yes, they move on to the next idea.

In 2010, when Contagious first profiled the aggressively independent beer-maker, it brewed 1.58 million litres of ale annually and had just opened its first bar. In 2017 BrewDog expanded to the US with a second destination brewery that increased its brewing capacity to 1.64 million hectolitres, more than a hundred times that 2010 number. That was good enough to make it the fastest-growing craft brewer in the world, valued at over £1 billion. Its portfolio now includes eponymous bars and hotels, and the punks are reportedly even planning to launch a craft beer TV network, of all things.

DON’T JUST SIT THERE, DO SOMETHING

Creativity is only useful if you’re brave enough to deploy it. You’ll recall Tom Raith, portfolio director of brand experience design at IDEO, and his concept of ‘back of the deck ideas’ referenced in the seventh commandment. When agencies pitch a client, he told the audience at Contagious’s 2015 event in San Francisco, they often come with presentations that are mostly the same – generally similar ideas and tactics make up the majority of the pitch deck from agency to agency. Where the agencies differentiate themselves is toward the back of the deck, where they stick their exciting, creative, risky ideas. Clients often choose their agency based on these back-of-the-deck ideas, said Raith, but then pay them to execute only the front-of-the-deck concepts.

This is akin to buying a Lamborghini and only ever driving it to church.

We firmly believe that in today’s competitive landscape, bravery isn’t optional. It is a strategic imperative. In fact, working with marketing and sales consultancy OxfordSM, Contagious developed a framework for brands to activate many of the commandments explored in this book. We use that framework, called Fit for the Future Now, to encourage brands to take stock and prioritize according to what’s needed to grow today. ‘There’s so much noise and complexity that commercial teams have to cope with that it’s easy to lose sight of the few things that really matter,’ says Peter Kirkby, head of the capability practice at OxfordSM. One of those things that ‘really matter’? Acting with bravery.

The diagram of Fit for the Future Now will look familiar to anyone who has made it this far into this book, although a few of the words are different. There are two anchor points (‘Live your purpose’ and ‘Own a simple experience’), four behaviours and two enablers (‘Simplify’ and ‘Break through the data’).

None of the circles in the Fit for the Future Now diagram – and none of the commandments in this book – are more important than the others. You must do all of the above (and then some) to be a successful brand for the decades to come. But if we had to pick just one, you can probably guess which one it is by glancing at the cover of this book. You can have all the incredible ideas in the world, but if you don’t attempt to make them a reality and put them out into the world, if you don’t take risks in how you articulate your values and reach your consumers, if you don’t defy conventions and stick out from the crowded masses, the rest of it may not even matter.

‘There’s strong evidence from Peter Field’s analysis that a combination of great strategy and real creative bravery is up to six times more effective than great strategy and averagely creative work,’ says Kirkby. ‘This is down to what Peter Field calls the “fame effect” – creatively brave work gets talked about so has a multiplier effect that less creative work doesn’t.’

In the framework, Contagious and OxfordSM encourage brands to ask themselves a few simple questions around bravery:

// Do you have creative work that’s getting talked about?

// Do you have a way of asking agencies for it, and evaluating and selling it internally, that reflects how the odds are stacked against creativity in large companies?

// Do you have testing and learning about ‘next practice’ baked into how you work and budget?

Answering these questions can start to give you a process for bravery, and sense-check your ways of working to make sure they’re not defaulting to the tried-and-true.

IT ALL COMES DOWN TO THIS

Our hope is that this book can serve as a rallying cry for creativity. A practical guide to ignite exceptional ideas. We hope that when you set this book down you’ll walk away with nuggets of wisdom, practical case studies, and one or two dumb jokes you can’t quite get out of your head. But most of all, we hope that these ten Contagious Commandments give you the courage to follow your creative convictions and set ambitions above and beyond the status quo.

It’s far from easy. Defining your organizing principle requires soul searching for your company and its employees. Crafting services and communications that are useful, relevant and entertaining requires a deep understanding of your customers and the capabilities to deliver on that knowledge.

Asking heretical questions can be uncomfortable and challenging, even when they lead to breakthroughs and opportunity. Aligning with behaviour necessitates constant commitment to putting the customer at the centre of the way you work.

Giving generously and allocating budget to experiments can feel counterproductive to profits. But both make brands stronger and more valuable in the long run. Prioritizing experience over innovation in a world focused more on ‘latest’ than ‘greatest’ can feel out of step.

Making people a central part of how you both develop and disseminate messages is often unpredictable. Building trust takes time and transparency, both of which can be challenging (the former more for upstarts, the latter for legacy brands).

All of these challenges lead up to the last: bravery. Having the stomach for creativity requires courage to do what has never been done, or to break away from what has worked in the past, or to put something into the world without knowing how it will be received. But if you take the first nine commandments to heart, the last should be the easiest. Bravery isn’t a blind leap into the unknown, it’s a measured step into the unwritten future. Persevere in the face of uncertainty, because uncertainty isn’t going away. Although, really, who can even be sure of that?

Creativity is infectious. It connects to something primal in our DNA – to hunting legends painted on the walls of caves and tales told around campfires or in the bustle of marketplaces. There’s something fundamentally human about contagious ideas. People need to share, to relate, to connect, to persuade, to feel like we’re part of something bigger than ourselves. We believe brands can earn the right to add their voice to that cultural conversation, enriching the human experience in this fantastic but frenetic world of ours, if they stay true to these ten commandments. At the heart of each of the ten lies a simple truth: make people a priority. Understand and celebrate their needs, their whims, their desires, their fears, their frustrations and, above all, their brilliant idiosyncrasies. Be generous with your creativity, be brave with your vision. And, if you like what you have read, pass it on.

BE BRAVE / ESPRESSO VERSION

Nothing ventured, nothing gained. You miss all of the shots you don’t take. Shoot for the moon; even if you miss you’ll end up among the stars. Whatever your favourite cliché about bravery, in the marketing world it’s probably more true today than it has ever been. The fracturing of audiences and evaporation of barriers to advertising entry means that creativity is the last true long-term competitive advantage in the modern marketplace. Creative work is, simply, more efficient and more effective than non-creative work.

Creative work is also scary. It takes effort to approve bold ideas and challenge conventions. After all, people rarely get fired for playing it safe. But if we want not just to survive but to thrive, we have to fight against our every instinct to retreat to safety and skate by with ‘good enough’. We’re hardwired to avoid risk, and consequently we need to dig deep to find the courage to go with our gut and to invest in our instincts.

But there’s a thin line between bravery and foolishness – a line we’d like you to stay on the correct side of. That’s exactly why we advise you to think of bravery in terms of measured risk. Some experiments succeed and some blow up the lab. Create the right ecosystem for intelligent bravery, and hopefully you’ll avoid the latter outcome.

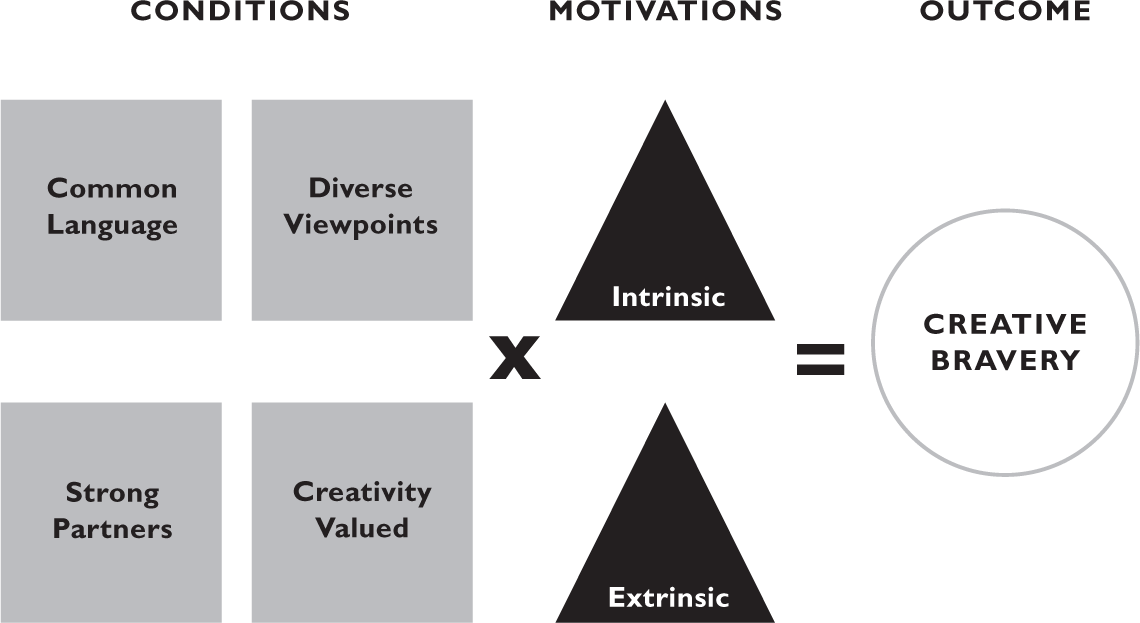

So how do you create an ecosystem for bravery to thrive? We think it boils down to establishing the right starting conditions, and catalysing them with a combination of intrinsic (driven by passion) and extrinsic (driven by reward) motivations.

To make sure you have the right conditions in place, ask yourself the following questions:

// Do we, as an organization, have the terminology to talk about creative ideas in concrete and universal language? You can gather the smartest beings in the universe in a single room, but unless they can communicate with each other, it won’t amount to a hill of beans.

// Are we inviting new voices to take part in our conversations, and attempting to involve as many different perspectives as possible? Without fresh eyes and different viewpoints, you’re only getting a thin slice of what’s possible.

// Do we have a strong working relationship with partners who are also willing to be brave? Think of brave creativity like a nuclear decision – two parties need to turn their keys to make it a reality.

// Have we bought into bravery at a core level? If your bravest ideas get spiked at the end of a long journey to the top, you can say goodbye to getting similarly brave work in the future.

If the right ecosystem is in place, you need to motivate people to take advantage of those environmental effects. Ask yourself:

// Are we hiring people who are driven by a passion for bold, creative ideas?

// Are we creating an environment where that passion is fuelled and encouraged?

// Are we motivating people to make truly creative work by offering rewards that they actually want? What could we offer that would be even better?

Occasionally, creative bravery can happen overnight. But more often it’s the result of months or years of work. Bravery is a muscle. Creativity is a muscle. Marketing is a muscle. Sit back, and it will atrophy. Push your organization to be stronger, and it will develop.

We hope this book has given you a set of tools and strategies that will help you get closer to your audience, understand why and how your company can best serve those people, and to grow your brand by creating exceptional ideas that will enhance and enrich their lives. Push yourself to do those things. We think you’ll find it’s contagious.