POETRY OF THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST:

THE ARC OF THE EDIFICE

NATIVE PEOPLE of the Northwest had no choice but to live in relation to poetry from the very outset of creation. We had to learn to identify and convert the individual elements of earth into forms of protection and sustenance, a so-called lifestyle. This would involve courtship, and gathering of every necessary berry, moss, bark, and wood. I remember stories of Suquamish women leaving for several days on summer journeys over the Cascade Mountains into eastern Washington to gather luminous bear grass, those pieces that would sometimes tell stories along the outer surface of our baskets.

This draping of my history within the landscape has become an available arc that we tap into at will. Michael Wasson’s “Poem for the háawtnin’ & héwlekipx” [The Holy Ghost of You, the Space & Thin Air] is driven by a similar recognition as well as a willingness to reveal aspects of composition within the poem itself:

I imagine

smudging my tongue along a wall

like the chest

I dare to plunge in-

to, the Braille of every node

blooming out

as if the first day-

light of wintered

snowfall.

The surfaces gained in Wasson’s poem are intensely reflective, throwing light at every break in the line. The poem forms an enclosure around its reader; nothing so simple as a hall of mirrors, this feels more like an alchemical bath. The poet is being reborn and seemingly splintered back into the natural world.

Gloria Bird is another master of the lyric, often leaving a secret door (or mirror) in the turn of her lines, hinting at another arc the poem might have taken. She dissolves the needless walls between syllables through an ingrained, behind-the-beat feel for phrasing, and this hypnotic rhythm often takes the lead in unlocking her expansive imagery:

appointed places set in motion like seasons. We are like salmon

swimming against the mutation of current to find

our heartbroken way home again, weight of red eggs and need

Duane Niatum’s lines are as deeply graven as those of any bent-wood box or totem carving. His work reminds us that poetry can incur the weight and grandeur of a ceremonial object. I seem to remember his poems as a series of interconnected, colorful weavings intent on charting a poet’s journey in and out of the realm of magic. He seems to soar above the poem as it is being uncovered and to light each of his images individually:

I camp in the light of the fox

Within the singing mirror of night,

Hunt for courage to return to the voice

Whirling my failures through the meadow

Elizabeth Woody’s work uses elements of traditional art-making to recast her tribal narrative as one of continued survival. Her poems feel like power deconstructed, as only a sculptor might attempt, language arranged into objects we cannot turn away from. We witness her incredible agency and all-enveloping tone throughout “Translation of Blood Quantum”:

THIRTY-SECOND PARTS OF A HUMAN BEING

SUN MOON EVENING STAR AT DAWN CLOUDS

RAINBOW CEDAR

LANGUAGE COLORS AND SACRIFICE LOVE

THE GREAT FLOOD

THE TORTOISE CARRIES THE PARROT HUMMINGBIRD TRILLIUM

After breaking into this imaginative and itemized list (this is only an excerpt), she goes on to detail her sense of what a politics of self-determination looks like and how to actualize this energy within our work:

Our Sovereignty is permeated, in its possession

of our individual rights, by acknowledgment of good

for the whole

and this includes the freedom of the Creator in these teachings

given to and practiced by The People.

Poetry can contain so many types of voices within one instance of writing; its restlessness and need for flexibility are two of its greatest strengths. This sensation can border upon utopia as syllabic, concrete-sounding sections of a poem may lie next to restorative political strategies and then begin to break into rhythms of incantation and chant. I tend to cast Elizabeth Woody’s work in a heroic light because of her unwavering willingness to write the world she wants to live in as well as for her willingness to speak for more than just herself. She defines our struggle as ongoing, as an eternal and aspirational state, a substance from which we are meant to form poetry as well as to speak out in protest. Her poem is reminiscent of Chief Seattle’s speech during the treaty negotiations of 1854 addressing then-governor of Washington State, Isaac Stevens:

And when the last red man shall have perished from the earth and his memory among the white men shall have become a myth these shores will swarm with the invisible dead of my tribe; and when your children’s children shall think themselves alone in the fields, the store, the shop, upon the highway, or in the silence of the pathless woods, they will not be alone. In all the earth there is no place dedicated to solitude.

Just as we first formed a poetry out of our literal surroundings, we then had to move on to preserving these traditions as they were quickly becoming outlawed by the U.S. government. When elements of trauma begin to surface within our histories, the action begins to be told in reverse. To this day we are still fighting to be seen as living, breathing, contemporary artists.

I have come to think of Native Poets as warrior/prophets that can move (almost routinely) beyond our own bodies. We are hovering, scribing entities, free to drop back into our trenches as needed. It is the poems themselves that provide the bedrock for further resistance and redefinition. Becoming a better listener is also such a huge part of becoming a more complete poet, to always leave ourselves open to new frequencies. This collection will no doubt spark new changes and touchstones for artists of every discipline.

POETRY OF ALASKA

ALASKA—A RUGGED LAND of gold; the great land; the last frontier—these are the descriptions of newcomers, but for Alaska Native people it is life, and the home of ancestors. In contrast, the seven Iñupiaq, five Tlingit, one Yup´ik, two Athabascan, and one Aleut (Tangirnaq) writers reflect an eternal connection to place that runs through their veins cycling through the generations.

Beginning with the singing words shared by Lincoln Blassi appealing to the “Whale of distant ocean,” the intimate knowledge of land and sea offerings of the treeless and windswept St. Lawrence Island is evident. In this most remote northwestern environment and Siberian Yup´ik culture, time is polychronic, cyclical, as it is with all Alaska’s indigenous peoples and is clear in this reverence of the whale harvest season. Respect of the landscape and what it holds is an important thread for continuance—the people are not separate from the landscape but a part of it. They belong to it. It is this that is shared from one indigenous group to the next in this vast and diverse land called Alaska.

There are loosely seven different regions of Alaska that by their size and geographic differences could be countries within their own right: Southeast, Northeast, Aleutians, Northwest, North, South Central, and the Interior. Unlike many other tribes in the United States, Alaskan tribes still exist on the very land of their ancestors. The Alaskan poets represented here have all had the benefit of either living in their community of origin, or returning to it.

Alaskan tribes speak twenty distinct languages and numerous dialects. Each distinct language is representative of a distinct culture intrinsically woven into time and space of place. Language represents not only the values and social systems but the relationship to land and to its subsequent spiritual realities. Interestingly, we see this even in English—in the poems of the poets across the generations from “Spirit Moves,” by Fred Bigjim, to “Anatomy of a Wave” by Abigail Chabitnoy. The voices of the old ones, the dark secrets held by the landscape, are present in the poetry. And all the while life, indigenous life, insists on finding a way.

The regions of Alaska that are the origins of these poets are the terrain of their poetic souls.

Contained by glacial fields, Southeast Alaska’s spruce-covered mountains dive into the sea, facing islands and rugged coasts, where rain can be relentless. It is a place of abundance—rich with berries, mammals, deer, sea greens, and fish. Tlingit story, friendship, and life all revolve through the sharing of this wealth no matter the location, as in “How to make good baked salmon from the river” by Nora Marks Dauenhauer. Although having to adapt, ancestral relatives are still present and remembered and all are nourished.

Family is always central, and for the Interior Athabascans life along the many rivers and birch-wooded forests through harsh winters and hot, dry summers is reliant on their unity and reciprocity. Although Dian Million was removed from Alaska at the age of twelve, she illustrates this timeless principle in “The Housing Poem.” Mary TallMountain, also of the same region and similar circumstance, alliterates the sharing of grease from caribou, and gently brings home to the reader the deeply held bonds that go beyond time and distance in her two poems, “Good Grease” and “There is No Word for Goodbye.”

The voice of Alaska Native poets began to challenge the status quo and twist the canon around the end of World War Two, when Alaska Native people became the minority demographic: many were forced off to boarding schools, and traditions and languages were banned. Conflicting worldviews and painful ironies emerge as acculturation meets cultural studies in “At the Door of the Native Studies Director,” by Robert Davis Hoffman. Andrew Hope III, in one of his less minimalist poems, “Spirit of Brotherhood,” creates a cross-rhythmic theme of religion and cultural adaptation as he situates the cultural placement of the oldest Native American organization, the Alaska Native Brotherhood.

Dominant in much of the Alaskan poetry is the reality of loss, cultural disruption, and the effort to reconcile cultural existence in a continually colonizing and commodifying world. What is notable is that voice is given to these themes primarily by more recent poets. This is evident in a number of poems by Iñupiaq writers Joan Kane, Cathy Tagnak Rexford, Carrie Ayaġaduk Ojanen, and Ishmael Hope—all of whom were born long after the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971. Internal and external struggles are laid bare in the poetry and are seemingly interwoven into historical trauma and circumpolar politics by this generation now coping with the undeniable urgency of global threats to subsistence and humanity, climate change, and war. Inupiat are on the front line of the north, and these poets, perhaps influenced by the activists before them, speak to current issues and their own fragility juxtaposed with Alaskan Native life that often appears to be teetering on the edge. Even in the darkness, there remains a glowing undercurrent of perseverance.

POETRY OF THE PACIFIC

THROUGH INCORPORATED and unincorporated territories, free associated states, and ocean monuments, the United States currently controls one-third of the Pacific Ocean, which itself comprises one-third of the earth’s surface. Continuing manifest destiny beyond the continental borders, the United States formally annexed Hawaiʻi and Guåhan (Guam) in 1898 and Amerika Sāmoa in 1900 to bolster militarization and trade in the Asia-Pacific region. Though dominant historical narratives are vague and imply that American colonialism has been benevolent and beneficial for us, they conveniently omit the violence behind the establishment and ongoing maintenance of American empire in (and because of the location of) our islands in the Pacific. These colonial stories also enable tourism, another leading economic industry in our region, to profit from exploitative images of us as happy, simple natives living in a paradise that is open and ready to serve.

If you ask for our stories, however, you will likely hear our poetry, the genre we tend to prefer, which stands as testament to the superficiality and brevity of the United States in the Pacific; to the resilience, ingenuity, and strength of our communities; and to our fierce love for our islands and ocean, our cultures, and our ancestors. It would not be an overstatement to share that there is a poet, an orator with a love and healthy reverence for the power of language, in every Pacific family. Therefore, this section showcases only a few of the poets from Hawai‘i, Amerika Sāmoa, and Guåhan and should definitely not be considered exhaustive. There are many others whose powerful, wise, inspiring, and talented voices fill other books and anthologies, lift our peoples through movements and rallies, heal our hearts, and nourish our imaginations.

Given the diversity of our cultures, languages, histories, and political issues in the Pacific, I will treat each Pacific archipelago separately and begin with Hawaiʻi, as the Pacific selections start with the first wā (epoch) in the Kumulipo, a genealogical chant tracing more than eight hundred human generations—as well as plant and animal ancestors—that emerge after the universe comes into being. The first wā details cosmogenesis as spontaneous and generative, ending with the birth of night. Though the Kumulipo was first recorded in writing under the direction of King David Kalākaua, who reigned from 1874 to 1891, Queen Liliʻuokalani began the translation in 1895 while imprisoned in ‘Iolani Palace in Honolulu and completed it in 1897 in Washington, D.C., as she lobbied against Hawaiʻi’s annexation to the United States. The Kumulipo has since become one of the most important poems of our people.

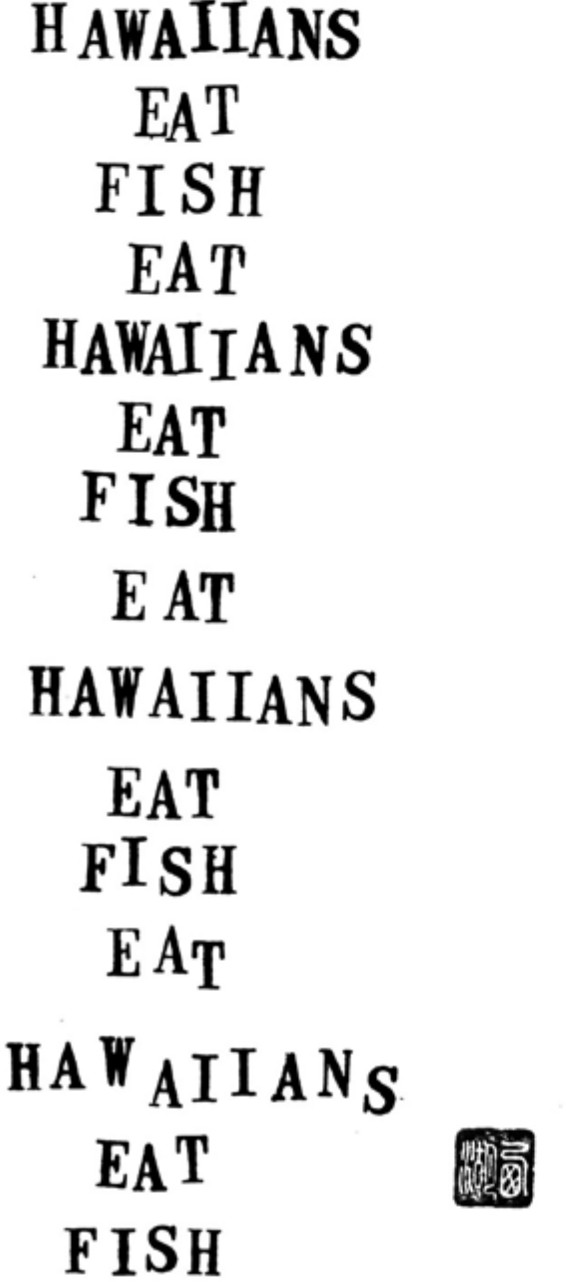

Literary scholar and poet kuʻualoha hoʻomanawanui uses the metaphor of the haku (braided) lei to describe how Hawaiian poems use overlapping meanings, interweave traditions, and yet adhere to craft and structure. Though applied to Hawaiian poetry, the metaphor holds true for all of the contemporary Pacific selections that follow. We begin with John Dominis Holt’s “Ka ʻIli Pau,” a poem reflecting on how we are continuations of our ancestors, and Leialoha Perkins’ “Plantation Non-Song,” a strong indictment of Hawaiʻi’s sugar plantations for fostering “ghettos of mind, slums of the heart.” Holt first published in 1965 and Perkins in 1979, following the near extinction of the Hawaiian language and other forms of colonial silencing since annexation in 1898. The next generation of poets began writing in the 1980s and ’90s—Imaikalani Kalahele, Michael McPherson, Mahealani Perez-Wendt, Dana Naone Hall, Joe Balaz, Wayne Kaumualii Westlake, and Haunani-Kay Trask. Their poems are emblematic of their political activism and ancestrally rooted commitment to social and environmental justice. Kalahele’s “Make Rope,” McPherson’s “Clouds, Trees, & Ocean: North Kauaʻi,” Balaz’s “Charlene,” Westlake’s “Hawaiians Eat Fish,” and Trask’s “Night is a Sharkskin Drum” and “Koʻolauloa” emphasize continuance and ongoing connections to ʻāina (land) and suggest we are able to move between ancestral time and our own. In these poems, the poet’s duty is to “become the memory of our people” (Kalahele). Perez-Wendt’s “Uluhaimalama,” Hall’s “Hawaiʻi ’89,” and Trask’s “Agony of Place” lay bare and fight the ravages of American colonialism “grinding vision/ from the eye, thought/ from the hand/ until a tight silence/ descends” (Trask), while also taking spiritual sustenance in ancestral connection and the land’s enduring beauty, “feast[ing] well/ On the stones” (Perez-Wendt) and “blooming [like kokiʻo] on the long branch” (Hall). Notably, much of the poetry of this period is lyrical and elegaic, yet insistent on how healing is rooted in our return to culture and ʻāina.

Poets who began writing in the 2000s and 2010s, including Christy Passion, Donovan Kūhiō Colleps, Noʻu Revilla, Jamaica Heolimeleikalani Osorio, and myself, share intimate portraits of ʻohana (family) and continue the work of truth-telling and memory-keeping alongside political activism and community engagement. As it was for the poets before us, ancestral connection, which includes human, plant, and animal ancestors, is a significant thematic thread, one that informs a predilection for decoloniality. My sonnet series “Ka ʻŌlelo” allays the trauma of the English-only law through a love song for my grandfather and ‘ōlelo Hawaiʻi (the Hawaiian language); and “He Mele Aloha no ka Niu” honors the generosity of the niu, or coconut. Passion’s “Hear the Dogs Crying” and Colleps’s “Kiss the Opelu” lovingly invoke sonicality in rendering their grandmothers’ stories. Similarly, the moving “Smoke Screen” by Revilla imagines her father’s days working at the sugar mill where he “marr[ied] metal in his heavy/ gloves . . . He was always burning into something.” The last of the Pacific selections, Osorio’s “Kumulipo,” is a spoken-word poem referencing Liliʻuokalani’s Kumulipo and voicing her own genealogy to stave off colonial forgetting. Perhaps diverging from their predecessors, these poets openly reflect on issues of cultural and political identity, including language, gender, and sexual identity, and use the lyric and other forms to show the trauma of colonial loss and violence experienced by the ʻohana, while also affirming a strong commitment to justice and sovereignty.

The work of American empire and militarism has also meant Indigenous displacement and a growing Pacific Islander diaspora—to the point that some off-island populations outnumber their on-island kin. In their poetry collections Dan Taulapapa McMullin (from Amerika Sāmoa), Craig Santos Perez (who is CHamoru from Guåhan), and Lehua M. Taitano (who is also CHamoru from Guåhan) all write from the diaspora, sharing their individual stories of having to leave their home islands. Here, McMullin’s “Doors of the Sea” lyrically follows an overseas journey that separates brothers and plays with gendered language, a signature of McMullin’s faʻafafine (non-binary) perspective. Perez’s “ginen the micronesian kingfisher [i sihek]” mourns the loss of birdsong after U.S. military ships brought brown tree snakes to the island and details colonial efforts to save the Micronesian kingfisher. Finally, Taitano’s “Letters from an Island” offers us a glimpse into a family’s correspondence between Guåhan and the continental United States. Both Perez and Taitano are avant-garde poets who incorporate CHamoru language and culture, visuality, history, and politics into their poetics. Collectively, these writers, like others in the Pacific, are creating new literatures in order to honor our ancestors, remember our histories, revitalize our cultures, decolonize our islands and ocean, and imagine sovereign futures.

The Kumulipo is a Hawaiian creation chant. Below is the version recorded in writing under the direction of King David Kalākaua. The accompanying translation into English was completed by Queen Liliʻuokalani in 1897. King Kalākaua reigned over the Hawaiian Kingdom from 1874 until his death in 1891. His sister, Queen Liliʻuokalani, succeeded him on the throne. They were the last two monarchs of the Hawaiian Kingdom before the U.S. military–backed overthrow in 1895.

O ke au i kahuli wela ka honua

O ke au i kahuli lole ka lani

O ke au i kukaiaka ka la.

E hoomalamalama i ka malama

O ke au o Makali’i ka po

O ka walewale hookumu honua ia

O ke kumu o ka lipo, i lipo ai

O ke kumu o ka Po, i po ai

O ka lipolipo, o ka lipolipo

O ka lipo o ka la, o ka lipo o ka po

Po wale hoi

Hanau ka po

[Translation into English]

At the time that turned the heat of the earth,

At the time when the heavens turned and changed,

At the time when the light of the sun was subdued

To cause light to break forth,

At the time of the night of Makalii (winter)

Then began the slime which established the earth,

The source of deepest darkness.

Of the depth of darkness, of the depth of darkness,

Of the darkness of the sun, in the depth of night,

It is night,

So was night born

CHIEF SEATTLE (1786–1866), Suquamish and Duwamish. The city of Seattle, Washington, is named after Chief Seattle, who ruled over both the Suquamish and the Duwamish though the two tribes were separated by the Puget Sound. In addition to his leadership skills and his ability to understand the intentions of the white settlers, he was also a noted orator in the Northern Lushootseed language. During the treaty proposals of 1854, Chief Seattle delivered a speech that is still remembered today. At the time of his death, protests over treaty rights and resettlement were still ongoing.

CHIEF SEATTLE (1786–1866), Suquamish and Duwamish. The city of Seattle, Washington, is named after Chief Seattle, who ruled over both the Suquamish and the Duwamish though the two tribes were separated by the Puget Sound. In addition to his leadership skills and his ability to understand the intentions of the white settlers, he was also a noted orator in the Northern Lushootseed language. During the treaty proposals of 1854, Chief Seattle delivered a speech that is still remembered today. At the time of his death, protests over treaty rights and resettlement were still ongoing.

Excerpts from a Speech by Chief Seattle, 1854

The speech was originally transcribed by Dr. Henry Smith into a trade language known as Chinook Jargon before he attempted his own translation into English. The speech was transcribed into Northern Lushootseed by Vi Hilbert, July 27, 1985, then subsequently into English.

Your religion was written on tablets of stone by the iron finger of an angry God, lest you forget.

The red man could never comprehend nor remember it. Our religion is the tradition of our ancestors, the dreams of our old men, given to them in the solemn hours of the night by the great spirit and the visions of our leaders, and it is written in the hearts of our people.

Your dead cease to love you and the land of their nativity as soon as they pass the portals of the tomb; they wander far away beyond the stars and are soon forgotten and never return. Our dead never forget this beautiful world that gave them being. They always love its winding rivers, its sacred mountains, and its sequestered vales, and they ever yearn in tenderest affection over the lonely hearted living and often return to visit, guide and comfort them.

We will ponder your proposition, and when we decide we will tell you. But should we accept it, I here and now make this the first condition that we will not be denied the privilege, without molestation, of visiting at will the graves where we have buried our ancestors, and our friends and our children. Every part of this country is sacred to my people. Every hillside, every valley, every plain and grove has been hallowed by some fond memory or some sad experience of my tribe.

Even the rocks which seem to lie dumb as they swelter in the sun along the silent seashore in solemn grandeur thrill with memories of past events connected with the lives of my people.

And when the last red man shall have perished from the earth and his memory among the white men shall have become a myth, these shores will swarm with the invisible dead of my tribe; and when your children’s children shall think themselves alone in the fields, the store, the shop, upon the highway, or in the silence of the pathless woods, they will not be alone. In all the earth there is no place dedicated to solitude.

At night when the streets of your cities and villages will be silent and you think them deserted, they will throng with returning hosts that once filled and still love this beautiful land. The white man will never be alone. Let him be just and deal kindly with my people, for the dead are not powerless.

Dead—did I say? There is no death, only a change of worlds.

[Translated by Vi Hilbert]

LINCOLN BLASSI (1892–1980), St. Lawrence Island Yup´ik, was born in Gambell, Alaska, where he worked as a whaling harpooner. The story of his childhood appeared in the July and August 1978 issues of Alaska Magazine. As the number of the region’s whales decreased, Blassi sold his ceremonial whaling gear, which the ethnographer Otto Geist acquired for the University of Alaska Museum of the North.

LINCOLN BLASSI (1892–1980), St. Lawrence Island Yup´ik, was born in Gambell, Alaska, where he worked as a whaling harpooner. The story of his childhood appeared in the July and August 1978 issues of Alaska Magazine. As the number of the region’s whales decreased, Blassi sold his ceremonial whaling gear, which the ethnographer Otto Geist acquired for the University of Alaska Museum of the North.

Prayer Song Asking for a Whale

(told in St. Lawrence Island Yup´ik)

IVAGHULLUK ILAGAATA

Ighivganghani, eghqwaaghem elagaatangi taakut atughaqiit. Ilagaghaqut angyalget taakut. Ivaghullugmeng atelget.

Elngaatall, repall tusaqnapangunatengllu. Nangllegsim angtalanganeng, wata eghqwaalleghmi tawani nangllegnaghsaapiglluteng ilaganeghmeggni iglateng qughaghteghllaglukii piiqegkangit. Nangllegsim angtalanganeng Kiyaghneghmun.

Uuknaa-aa-aanguu-uuq.

Saamnaa-aa-aanguu-uuq,

Taglalghii-ii-ii saa-aamnaa.

Ketangaa-aan aghveghaa-aa saa-aamnaa-aa

Aghvelegglaguu-uu-lii.

Ellngalluu-uu-uu.

Qagimaa iluganii-ii-ii.

Uuknaa-aa-aanguu-uuq.

Saamnaa-aa-aanguuq,

Taglalghii-ii-ii saa-aamnaa.

Ketangaa-aa-aan ayveghaa-aa saa-aamna.

Aghvelegllaaguluu-uu-lii

Elngaa-aa-aalluu-uungu-uuq

Qagimaa iluganii-ii-ii.

Uuknaa-aa-aanguu-uuq.

Saamnaa-aa-aanguu-uuq

Taglalghii-ii-ii saa-aamnaa.

Ketangaa-aan maklagaa-aa-aanguuq.

Aghvelegllaguulii-ii-iingii.

Ellngalluu-uu-uu.

Qagimaa iluganii-ii-ii-ngiy.

Before the whaling season, the boat captain would sing ceremonial songs in the evening. The ceremony of singing was called ivaghulluk.

The boat captain would sing these songs in such a low reverent voice that you could hardly make out the words. Especially before the whaling season began, the songs of petition were sung to God in a prayerful pleading voice.

The time is almost here.

The season of the deep blue sea . . .

Bringing good things from the deep blue sea.

Whale of distant ocean . . .

May there be a whale.

May it indeed come . . .

Within the waves.

The time is almost here.

The season of the deep blue sea . . .

Bringing good things from the deep blue sea.

Walrus of distant ocean . . .

May there be a whale.

May it indeed come . . .

Within the waves.

The time is almost here.

The season of the deep blue sea . . .

Bringing good things from the deep blue sea.

Bearded seal of distant ocean . . .

May there be a whale.

May it indeed come . . .

Within the waves.

MARY TALLMOUNTAIN (1918–1994), Koyukon, was a poet, stenographer, and educator. Born in Nulato, Alaska, along the Yukon River, she was adopted and relocated to Oregon. In her later years she moved to San Francisco, started her own stenography business, and began to write poetry. She is the author of The Light on the Tent Wall (1990), A Quick Brush of Wings (1991), and the posthumous collection Listen to the Night (1995). While living in San Francisco she founded the Tenderloin Women Writers Workshop, which supported women’s literary expression.

MARY TALLMOUNTAIN (1918–1994), Koyukon, was a poet, stenographer, and educator. Born in Nulato, Alaska, along the Yukon River, she was adopted and relocated to Oregon. In her later years she moved to San Francisco, started her own stenography business, and began to write poetry. She is the author of The Light on the Tent Wall (1990), A Quick Brush of Wings (1991), and the posthumous collection Listen to the Night (1995). While living in San Francisco she founded the Tenderloin Women Writers Workshop, which supported women’s literary expression.

The hunters went out with guns

at dawn.

We had no meat in the village,

no food for the tribe and the dogs.

No caribou in the caches.

All day we waited.

At last!

As darkness hung at the river

we children saw them far away.

Yes, they were carrying caribou!

We jumped and shouted!

By the fires that night

we feasted.

The Old Ones chuckled,

sucking and smacking,

sopping the juices with sourdough bread.

The grease would warm us

when hungry winter howled.

Grease was beautiful—

oozing,

dripping and running down our chins,

brown hands shining with grease.

We talk of it

when we see each other

far from home.

Remember the marrow

sweet in the bones?

We grabbed for them like candy.

Good.

Gooooood.

Good grease.

Sokoya, I said, looking through

the net of wrinkles into

wise black pools

of her eyes.

What do you say in Athabascan

when you leave each other?

What is the word

for goodbye?

A shade of feeling rippled

the wind-tanned skin.

Ah, nothing, she said,

watching the river flash.

She looked at me close.

We just say, Tłaa. That means,

See you.

We never leave each other.

When does your mouth

say goodbye to your heart?

She touched me light

as a bluebell.

You forget when you leave us;

you’re so small then.

We don’t use that word.

We always think you’re coming back,

but if you don’t,

we’ll see you some place else.

You understand.

There is no word for goodbye.

JOHN DOMINIS HOLT (1919–1993), Kanaka Maoli, was a poet, short-fiction writer, novelist, publisher, and cultural historian whose collective works contributed to the rise of the second Hawaiian renaissance movement in the 1960s and ’70s. He received several honors and accolades, including recognition as a Living Treasure of Hawai‘i in 1979 and the Hawai‘i Award for Literature in 1985. Additionally, Holt started Topgallant Press (Ku Paʻa Press), which published numerous books by authors in Hawaiʻi.

JOHN DOMINIS HOLT (1919–1993), Kanaka Maoli, was a poet, short-fiction writer, novelist, publisher, and cultural historian whose collective works contributed to the rise of the second Hawaiian renaissance movement in the 1960s and ’70s. He received several honors and accolades, including recognition as a Living Treasure of Hawai‘i in 1979 and the Hawai‘i Award for Literature in 1985. Additionally, Holt started Topgallant Press (Ku Paʻa Press), which published numerous books by authors in Hawaiʻi.

Give me something from

The towering heights

Of blackened magma

Not a token thing

Something of spirit, mind or flesh, something of bone

The undulating form of

Mauna Loa

Even lacking cold and mists

Or the dark of night, it

Is always forbidding: there is a love

That grows between us.

Ka ‘ili pau, you are a crazed ʻanā-ʻanā

With a shaman’s tangled hair,

Reddened eyes, and his

Laho—maloʻo.

He falls in love with his ʻumeke and its

Death giving objects.

These gifts form the times of confusion

Come from the mountain heights

Wild skies, deep valley cliffs and

Darkened caves

Where soft air creeps into darkness

Gently touching bones and

The old canoe’s prow

Inside the stunning skeletal remains

Of moe puʻu

My companions in death

My own skeleton stretches long

Across a ledge

Above the ancient remains

Of boat and bones

Give me your secrets locked

In lava crust

Give me your muscled power

Melted now to air and dust

Give me your whitened bones

Left to sleep

These many decades now as

The pua of your semen have multiplied down through

The centuries.

Sleep ali‘i nui and your

Companions

Sleep in your magic silence in

Your love wrapped in the total

Embrace of death

You have given us our place

Your seed proliferates

We are here

And we sing and laugh and love

And give your island home

A touch (here and there) of

Love and magic, these

Live in you makua aliʻi sleep on.

In your silence there is strength

Accruing for the kamaliʻi.

NORA MARKS DAUENHAUER (1927–2017), Tlingit, was a poet, fiction writer, and Tlingit language scholar. Born in Juneau, Alaska, to a fisherman and a beader, Dauenhauer researched Tlingit language and translated works of Tlingit culture at the Alaska Native Language Center. She received numerous honors and awards, including a National Endowment for the Humanities grant, a Humanist of the Year award, and an American Book Award. She also served as Alaska’s Poet Laureate from 2012 to 2014.

NORA MARKS DAUENHAUER (1927–2017), Tlingit, was a poet, fiction writer, and Tlingit language scholar. Born in Juneau, Alaska, to a fisherman and a beader, Dauenhauer researched Tlingit language and translated works of Tlingit culture at the Alaska Native Language Center. She received numerous honors and awards, including a National Endowment for the Humanities grant, a Humanist of the Year award, and an American Book Award. She also served as Alaska’s Poet Laureate from 2012 to 2014.

(Regional Basketball “All-American Hall of Famer”)

Even your name

proclaims it.

In Tlingit: S’ukkées,

“Wolf Rib, Like a Bracelet,

Like a Hoop.”

Scoring hook shots,

as center,

shooting from the key,

your body motion

forming a hoop

wolfing up the points.

I dance with

dancing cranes

(lilies of the valley),

transplanting them

under a tree until

next summer

when there will be

more dancers.

How to make good baked salmon from the river

for Simon Ortiz

and for all our friends and relatives

who love it

It’s best made in dry-fish camp on a beach by a

fish stream on sticks over an open fire, or during

fishing or during cannery season.

In this case, we’ll make it in the city, baked in

an electric oven on a black fry pan.

INGREDIENTS

Barbecue sticks of alder wood.

In this case the oven will do.

Salmon: River salmon, current super market cost

$4.99 a pound.

In this case, salmon poached from river.

Seal oil or olachen oil.

In this case, butter or Wesson oil, if available.

DIRECTIONS

To butcher, split head up the jaw. Cut through,

remove gills. Split from throat down the belly.

Gut, but make sure you toss all to the seagulls and

the ravens, because they’re your kin, and make sure

you speak to them while you’re feeding them.

Then split down along the back bone and through

the skin. Enjoy how nice it looks when it’s split.

Push stake through flesh and skin like pushing

a needle through cloth, so that it hangs on stakes

while cooking over fire made from alder wood.

Then sit around and watch the slime on the salmon

begin to dry out. Notice how red the flesh is,

and how silvery the skin looks. Watch and listen

to the grease crackle, and smell its delicious

aroma drifting around on a breeze.

Mash some fresh berries to go along for dessert.

Pour seal oil in with a little water. Set aside.

In this case, put the poached salmon in a fry pan.

Smell how good it smells while it’s cooking,

because it’s soooooooo important.

Cut up an onion. Put in a small dish. Notice how

nice this smells too, and how good it will taste.

Cook a pot of rice to go along with salmon. Find

some soy sauce to put on rice, maybe borrow some.

In this case, think about how nice the berries would

have been after the salmon, but open a can of fruit

cocktail instead.

Then go out by the cool stream and get some skunk

cabbage, because it’s biodegradable, to serve the

salmon from. Before you take back the skunk cabbage,

you can make a cup out of one to drink from the

cool stream.

In this case, plastic forks, paper plates and cups will do, and

drink cool water from the faucet.

TO SERVE

After smelling smoke and fish and watching the

cooking, smelling the skunk cabbage and the berries

mixed with seal oil, when the salmon is done, put

salmon on stakes on the skunk cabbage and pour

some seal oil over it and watch the oil run into

the nice cooked flakey flesh which has now turned

pink.

Shoo mosquitoes off the salmon, and shoo the ravens

away, but don’t insult them, because mosquitoes

are known to be the ashes of the cannibal giant,

and Raven is known to take off with just about

anything.

In this case, dish out on paper plates from fry pan.

Serve to all relatives and friends you have invited

to the barbecue and those who love it.

And think how good it is that we have good spirits

that still bring salmon and oil.

TO EAT

Everyone knows that you can eat just about every

part of the salmon, so I don’t have to tell you

that you start from the head, because it’s everyone’s

favorite. You take it apart, bone by bone, but make

sure you don’t miss the eyes, the cheeks, the nose,

and the very best part—the jawbone.

You start on the mandible with a glottalized

alveolar fricative action as expressed in the Tlingit

verb als’oss’.

Chew on the tasty, crispy skins before you start

on the bones. Eeeeeeeeeeeee!!!! How delicious.

Then you start on the body by sucking on the fins

with the same action. Include the crispy skins, then

the meat with grease dripping all over it.

Have some cool water from the stream with the salmon.

In this case, water from the faucet will do.

Enjoy how the water tastes sweeter with salmon.

When done, toss the bones to the ravens and

seagulls and mosquitoes, but don’t throw them in

the salmon stream because the salmon have spirits

and don’t like to see the remains of their kin

among them in the stream.

In this case, put bones in plastic bag to put

in dumpster.

Now settle back to a story telling session, while

someone feeds the fire.

In this case, small talk and jokes with friends

will do while you drink beer. If you shouldn’t

drink beer, tea or coffee will do nicely.

Gunalchéesh for coming to my barbecue.

LEIALOHA PERKINS (1930–2018), Kanaka Maoli, was a poet, publisher, fiction writer, and educator. She earned her PhD in folklore and folklife from the University of Pennsylvania. In 1998 she received the Hawai‘i Award for Literature. In addition to writing poetry, Perkins founded Kamalu‘uluolele Publishers, which specialized in Pacific Islands subjects as they relate to both East and West, and taught at universities in Hawaiʻi and Tonga.

LEIALOHA PERKINS (1930–2018), Kanaka Maoli, was a poet, publisher, fiction writer, and educator. She earned her PhD in folklore and folklife from the University of Pennsylvania. In 1998 she received the Hawai‘i Award for Literature. In addition to writing poetry, Perkins founded Kamalu‘uluolele Publishers, which specialized in Pacific Islands subjects as they relate to both East and West, and taught at universities in Hawaiʻi and Tonga.

Those years of lung-filling dust in Lahaina

of heat and humidity that induced

men and animals to lie down mid-afternoons

and sleep–between the mill’s lunch shift whistles–

were not great, but mediocre for most things

and superlative for doing or not doing anything

useful, ugly, or good. Just for staying out of trouble.

There was time and space for a child to grow up in

playing between scrabbly hibiscus bushes,

and hopping over rutty roads

that smelled of five-day-old urine, all on one side

of the canefield tracks, ground once blanketed

with warrior dead and sorcerer’s bones.

At the shore, the white newcomers lived

crossing themselves at sunrise and sunset

in a paradise “discovered,” jubilating

as Captain Cook who also had found the unfound natives

and their unfound shore naked and ready for instant use.

Mill Camp’s

beginnings are beginnings

one may grow to respect if not honor

because they are a man’s beginnings.

But let’s not make sentiment

the coin for the cheap treatment

some got–and others enjoyed handing out.

Let’s call the fair, fair.

What may have been good, good enough

because it was there,

like space waiting for time to fill it up

(while we were looking elsewhere);

nevertheless, plantation worlds

enjoyed their own tenors:

ghettos of mind, slums of the heart.

VINCE WANNASSAY (1936–2017), Umatilla, was a poet, writer, artist, and community worker. After some years on skid row he began writing and published in many anthologies, including Dancing on the Rim of the World: An Anthology of Contemporary Northwest Native American Writing (1990). He mentored many people in the Native community in the Portland, Oregon, area.

VINCE WANNASSAY (1936–2017), Umatilla, was a poet, writer, artist, and community worker. After some years on skid row he began writing and published in many anthologies, including Dancing on the Rim of the World: An Anthology of Contemporary Northwest Native American Writing (1990). He mentored many people in the Native community in the Portland, Oregon, area.

A LONG TIME AGO

WHEN I WAS A KID

I LIVED WITH MY

UNCLE AND AUNT

MY UNCLE RODE WITH

JOSEPH

WHEN HE WAS A KID . . .

I MEAN MY UNCLE NOT JOSEPH

UNCLE USE TO TELL US KIDS

COYOTE STORIES

SOME WERE FUNNY, SOME WEREN’T

MY MOTHER TOOK US, FROM UNCLE & AUNT

SHE PUT US IN A CATHOLIC BOARDING SCHOOL.

AT SCHOOL I TOLD SOME OF THE

COYOTE STORIES.

THE SISTERS SAID “DON’T BELIEVE

THOSE STORIES”. .

BUT BELIEVE US. . . . .

ABOUT A GUY

WHO WAVES A STICK . . . AND THE SEA OPENS

****

WALKS ON WATER

****

WHO DIES AND COMES BACK . . . TO LIFE AGAIN

****

WHO ASCENDS UP INTO THE SKY . . . . . . .

I USED TO BELIEVE ALL THOSE

STORIES

I DON’T ANYMORE.

NOW I WISH. . . . .I COULD

REMEMBER THOSE

COYOTE STORIES. . . . .UNCLE TOLD ME

DUANE NIATUM (1938–), Klallam, is a poet, fiction writer, and editor. After serving in the United States Navy, Niatum earned a PhD from the University of Michigan. Along with his creative works, Niatum served as an editor for Harper & Row’s Native American Authors series. Niatum has been the recipient of many awards and accolades, including the Governor’s Award from the State of Washington, the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Native Writers’ Circle of the Americas, and grants from the Carnegie Fund for Authors and PEN.

DUANE NIATUM (1938–), Klallam, is a poet, fiction writer, and editor. After serving in the United States Navy, Niatum earned a PhD from the University of Michigan. Along with his creative works, Niatum served as an editor for Harper & Row’s Native American Authors series. Niatum has been the recipient of many awards and accolades, including the Governor’s Award from the State of Washington, the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Native Writers’ Circle of the Americas, and grants from the Carnegie Fund for Authors and PEN.

He awoke this morning from a strange dream—

Thunderbird wept for him in the blizzard.

Holding him in their circle, Nisqually women

Turn to the river, dance to its song.

He burned in the forest like a red cedar,

His arms fanning blue flames toward

The white men claiming the camas valley

For their pigs and fowl.

Musing over wolf’s tracks vanishing in snow,

The memory of his wives and children

Keeps him mute. Flickering in the dawn fires,

His faith grows roots, tricks the soldiers

Like a fawn, sleeping black as the brush.

They laugh at his fate, frozen as a bat

Against his throat. Still, death will take

Him only to his father’s longhouse,

Past the flaming rainbow door. These bars

Hold but his tired body; he will eat little

And speak less before he hangs.

I camp in the light of the fox,

Within the singing mirror of night.

Hunt for courage to return to the voice,

Whirling my failures through the meadow

Where I watch my childhood pick

Choke cherries, the women cook salmon

On the beach, my Grandfather sings his song to deer.

When my heart centers inside the necklace

Of fires surrounding his village of white fir,

Sleeping under seven snowy blankets of changes,

I will leave Raven’s cave.

The years in the blood keep us naked to the bone.

So many hours of darkness we fail to sublimate.

Light breaks down the days to printless stone.

I sing what I sang before, it’s the dream alone.

We fall like the sun when the moon’s our fate.

The years in the blood keep us naked to the bone.

I wouldn’t reach your hand, if I feared the dark alone;

My heart’s a river, but it is not chilled with hate.

Light breaks down the days to printless stone.

We dance from memory because it’s here on loan.

And as the music stops, nothing’s lost but the date.

The years in the blood keep us naked to the bone.

How round the sky, how the planets drink the unknown.

I gently touch; your eyes show it isn’t late.

Light breaks down the days to printless stone.

What figures in this clay; gives a sharper bone?

What turns the spirit white? Wanting to abbreviate?

The years in the blood keep us naked to the bone.

Light breaks down the days to printless stone.

FRED BIGJIM (1941–), Iñupiaq, is a poet who grew up in Nome, Alaska. Earning graduate degrees from Harvard University and the University of Washington, Bigjim has published several collections of poetry, including Sinrock (1983) and Walk the Wind (1988), as well as non-fiction and fiction works. He has also worked as an educator and an educational counselor for Native American youth.

FRED BIGJIM (1941–), Iñupiaq, is a poet who grew up in Nome, Alaska. Earning graduate degrees from Harvard University and the University of Washington, Bigjim has published several collections of poetry, including Sinrock (1983) and Walk the Wind (1988), as well as non-fiction and fiction works. He has also worked as an educator and an educational counselor for Native American youth.

Sometimes I feel you around me,

Primal creeping, misty stillness.

Watching, waiting, dancing.

You scare me.

When I sleep, you visit me

In my dreams,

Wanting me to stay forever.

We laugh and float neatly about.

I saw you once, I think,

At Egavik.

The Eskimos called you a shaman.

I know better, I know you’re

Spirit Moves.

ED EDMO (1946–), Shoshone-Bannock, is a poet, playwright, performer, traditional storyteller, tour guide, and lecturer on Northwest tribal culture. He lectures, holds workshops, and creates dramatic monologues on cultural understanding and awareness, drug and alcohol abuse, and mental health. His poetry collection is These Few Words of Mine (2006).

ED EDMO (1946–), Shoshone-Bannock, is a poet, playwright, performer, traditional storyteller, tour guide, and lecturer on Northwest tribal culture. He lectures, holds workshops, and creates dramatic monologues on cultural understanding and awareness, drug and alcohol abuse, and mental health. His poetry collection is These Few Words of Mine (2006).

I sit in your

crowded classrooms

learn how to

read about dick,

jane & spot

but I remember

how to get deer

I remember

how to beadwork

I remember

how to fish

I remember

the stories told

by the old

but spot keeps

showing up &

my report card

is bad

PHILLIP WILLIAM GEORGE (1946–2012), Nez Perce, was a poet, writer, and champion traditional plateau dancer. His poem “Proviso” had been translated into eighteen languages worldwide and won multiple honors, including being performed on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson and The Dick Cavett Show. In addition to his poetry, George also wrote, produced, and narrated Season of Grandmothers for the Public Broadcasting Corporation.

PHILLIP WILLIAM GEORGE (1946–2012), Nez Perce, was a poet, writer, and champion traditional plateau dancer. His poem “Proviso” had been translated into eighteen languages worldwide and won multiple honors, including being performed on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson and The Dick Cavett Show. In addition to his poetry, George also wrote, produced, and narrated Season of Grandmothers for the Public Broadcasting Corporation.

They said, “You are no longer a lad.”

I nodded.

They said, “Enter the council lodge.”

I sat.

They said, “Our lands are at stake.”

I scowled.

They said, “We are at war.”

I hated.

They said, “Prepare red war symbols.”

I painted.

They said, “Count coups.”

I scalped.

They said, “You’ll see friends die.”

I cringed.

They said, “Desperate warriors fight best.”

I charged.

They said, “Some will be wounded.”

I bled.

They said, “To die is glorious.”

They lied.

IMAIKALANI KALAHELE (1946–), Kanaka Maoli, is a poet, artist, and musician. Writing in a combination of English, Pidgin (Hawaiian Creole English), and ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi, Kalahele seeks to honor ancestral knowledge while challenging colonial injustice. In addition to his poetry and art book Kalahele (2002), his poems have been published in several anthologies, including Mālama: Hawaiian Land and Water and ʻōiwi: a native hawaiian journal, and his art has been exhibited throughout the Pacific. The 2019 Honolulu Bienniale recognized his prolific contributions to art in Hawaiʻi by naming the event “Making Wrong Right Now” after a line from his poem “Manifesto.”

IMAIKALANI KALAHELE (1946–), Kanaka Maoli, is a poet, artist, and musician. Writing in a combination of English, Pidgin (Hawaiian Creole English), and ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi, Kalahele seeks to honor ancestral knowledge while challenging colonial injustice. In addition to his poetry and art book Kalahele (2002), his poems have been published in several anthologies, including Mālama: Hawaiian Land and Water and ʻōiwi: a native hawaiian journal, and his art has been exhibited throughout the Pacific. The 2019 Honolulu Bienniale recognized his prolific contributions to art in Hawaiʻi by naming the event “Making Wrong Right Now” after a line from his poem “Manifesto.”

get this old man

he live by my house

he just make rope

every day

you see him making rope

if

he not playing his ukulele

or

picking up his mo‘opuna

he making

rope

and nobody wen ask him

why?

how come?

he always making

rope

morning time . . . making rope

day time . . . making rope

night time . . . making rope

all the time . . . making rope

must get enuf rope

for make Hōkūle‘a already

most time

he no talk

too much

to nobody

he just sit there

making rope

one day

we was partying by

his house

you know

playing music

talking stink

about the other

guys them

I was just

coming out of the bushes

in back the house

and

there he was

under the mango tree

making rope

and he saw me

all shame

I look at him and said

“Aloha Papa”

he just look up

one eye

and said

“Howzit! What? Party?

Alright!”

I had to ask

“E kala mai, Papa

I can ask you one question?”

“How come

everyday you make rope

at the bus stop

you making rope

outside McDonald’s drinking coffee

you making rope.

How come?”

he wen

look up again

you know

only the eyes move kine

putting one more

strand of coconut fiber

on to the kaula

he make one

fast twist

and said

“The Kaula of our people

is 2,000 years old

boy

some time . . . good

some time . . . bad

some time . . . strong

some time . . . sad

but most time

us guys

just like this rope

one by one

strand by strand

we become

the memory of our people

and

we still growing

so

be proud

do good

and

make rope

boy

make rope.”

MICHAEL MCPHERSON (1947–2008), Kanaka Maoli, was a poet, publisher, editor, and lawyer. Interested in cultivating and maintaining a literature that was uniquely Hawaiian, McPherson wrote poetry, founded Xenophobia Press, and published the journal HAPA. In 1988, McPherson received a certificate of merit from the Hawai‘i House of Representatives, acknowledging his work and scholarship on Hawaiian literature. As a lawyer, McPherson worked on Native Hawaiian claims in environmental law and Hawaiian land use.

MICHAEL MCPHERSON (1947–2008), Kanaka Maoli, was a poet, publisher, editor, and lawyer. Interested in cultivating and maintaining a literature that was uniquely Hawaiian, McPherson wrote poetry, founded Xenophobia Press, and published the journal HAPA. In 1988, McPherson received a certificate of merit from the Hawai‘i House of Representatives, acknowledging his work and scholarship on Hawaiian literature. As a lawyer, McPherson worked on Native Hawaiian claims in environmental law and Hawaiian land use.

Clouds, Trees & Ocean, North Kauai

In Hā‘ena’s cerulean sky today

the cirrus clouds converge upon

a point beyond the summer horizon, all

hurtling backward: time

drawn from this world as our

master inhales.

The ironwoods lean down their dark needles

to the beach, long strings of

broken white coral and shells that ebb

to the north and west, and wait

dreaming the bent blue backs of waves.

MAHEALANI PEREZ-WENDT (1947–), Kanaka Maoli, is a poet, writer, and activist. Her poetry was recognized through the University of Hawai‘i’s Elliot Cades Award for Literature in 1993. She is the author of the poetry collection Uluhaimalama (2007) and her poems have been published in numerous anthologies. Perez-Wendt also has an extensive history of community engagement, formerly serving as executive director of Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation, serving as the first Native Hawaiian board member of the Native American Rights Fund, and working extensively with prison issues and sovereignty restoration.

MAHEALANI PEREZ-WENDT (1947–), Kanaka Maoli, is a poet, writer, and activist. Her poetry was recognized through the University of Hawai‘i’s Elliot Cades Award for Literature in 1993. She is the author of the poetry collection Uluhaimalama (2007) and her poems have been published in numerous anthologies. Perez-Wendt also has an extensive history of community engagement, formerly serving as executive director of Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation, serving as the first Native Hawaiian board member of the Native American Rights Fund, and working extensively with prison issues and sovereignty restoration.

We have gathered

With manacled hands;

We have gathered

With shackled feet;

We have gathered

In the dust of forget

Seeking the vein

Which will not collapse.

We have bolted

The gunner’s fence,

Given sacrament

On blood-stained walls.

We have linked souls

End to end

Against the razor’s slice.

We have kissed brothers

In frigid cells,

Pressing our mouths

Against their ice-hard pain.

We have feasted well

On the stones of this land:

We have gathered

In dark places

And put down roots.

We have covered the Earth,

Bold flowers for her crown.

We have climbed

The high wire of treason–

We will not fall.

WAYNE KAUMUALII WESTLAKE (1947–1984), Kanaka Maoli, was born on Maui and raised on the island of O‘ahu. With Richard Hamasaki, he created and edited the literary journal Seaweeds & Constructions from 1976 to 1983. His posthumous collection, Westlake: Poems by Wayne Kaumualii Westlake (1947–1984), edited by Mei-Li M. Siy and Richard Hamasaki (University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2009), includes nearly 200 poems, many previously unpublished.

WAYNE KAUMUALII WESTLAKE (1947–1984), Kanaka Maoli, was born on Maui and raised on the island of O‘ahu. With Richard Hamasaki, he created and edited the literary journal Seaweeds & Constructions from 1976 to 1983. His posthumous collection, Westlake: Poems by Wayne Kaumualii Westlake (1947–1984), edited by Mei-Li M. Siy and Richard Hamasaki (University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2009), includes nearly 200 poems, many previously unpublished.

DANA NAONE HALL (1949–), Kanaka Maoli, founded Hui Alanui o Mākena, an organization that successfully prevented the destruction of the Piʻilani Trail, a part of the road that once encircled Maui built by the aliʻi nui Piʻilani in the sixteenth century; and she has been at the forefront to protect iwi kupuna (ancestral remains) at Honokahua and other sacred burial sites. In addition, she is the editor of Mālama: Hawaiian Land and Water (1985). Her book Life of the Land: Articulations of a Native Writer (2017), a collection of poetry and memoir focused on her activism, won an American Book Award in 2019.

DANA NAONE HALL (1949–), Kanaka Maoli, founded Hui Alanui o Mākena, an organization that successfully prevented the destruction of the Piʻilani Trail, a part of the road that once encircled Maui built by the aliʻi nui Piʻilani in the sixteenth century; and she has been at the forefront to protect iwi kupuna (ancestral remains) at Honokahua and other sacred burial sites. In addition, she is the editor of Mālama: Hawaiian Land and Water (1985). Her book Life of the Land: Articulations of a Native Writer (2017), a collection of poetry and memoir focused on her activism, won an American Book Award in 2019.

for Leahi

The way it is now

few streams still flow

through lo‘i kalo

to the sea.

Most of the water

where we live

runs in ditches alongside

the graves of Chinese bones

where the same crop has burned in the fields

for the last one hundred years.

On another island,

a friend whose father

was born in a pili grass

hale in Kahakuloa,

bought a house on a concrete

pad in Hawai‘i Kai.

For two hundred thousand

he got window frames

out of joint and towel racks

hung crooked on the walls.

He’s one of the lucky ones.

People are sleeping in cars

or rolled up in mats on beaches,

while the lū‘au show hostess

invites the roomful of visitors

to step back in time

to when gods and goddesses

walked the earth.

I wonder what she’s

talking about.

All night, Kānehekili

flashes in the sky

and Moanonuikalehua changes

from a beautiful woman

into a lehua tree

at the sound of the pahu.

It’s true that the man

who swam with the sharks

and kept them away

from the nets full of fish

by feeding them limu kala

is gone,

but we’re still here

like the fragrant white koki‘o

blooming on the long branch

like the hairy leafed nehe

clinging to the dry pu‘u

like the moon high over Ha‘ikū

lighting the way home.

ANDREW HOPE III (1949–2008), Tlingit, was a poet and a Tlingit political activist. Born in Sitka, Alaska, Hope was the cofounder of the Tlingit Clan Conference as well as Tlingit Readers, a nonprofit publishing house. He married Iñupiaq poet Elizabeth “Sister Goodwin” Hope. Inspired by the work of Tlingit poet Nora Marks Dauenhauer, Hope used his poetry to help the Tlingit language remain alive in written form.

ANDREW HOPE III (1949–2008), Tlingit, was a poet and a Tlingit political activist. Born in Sitka, Alaska, Hope was the cofounder of the Tlingit Clan Conference as well as Tlingit Readers, a nonprofit publishing house. He married Iñupiaq poet Elizabeth “Sister Goodwin” Hope. Inspired by the work of Tlingit poet Nora Marks Dauenhauer, Hope used his poetry to help the Tlingit language remain alive in written form.

They sing Onward Christian Soldiers

Down at the ANB Hall

Every year in convention

The kids don’t like that song

They don’t like missionary history

We shove that in the closet nowadays

The church had little to do with

ANB adopting this battle song

William Paul, Sr. introduced it

after he heard it at Lodge 163 of A.F. and A.M.

Portland, Oregon

The Masonic Lodge influence

The song bothers me

That’s no secret

But

My people went into the church to survive

I don’t know what the pioneer days were like

Up here in gold rush Alaska

I listen to the Black church and think about the

music of the Black spirit

the gospel of Sam Cooke and the Soul Stirrers

Otis Redding and the others

That spirit catches you

When you walk into the meeting and feel like family

You’ll know what I’m saying

HAUNANI-KAY TRASK (1949–), Kanaka Maoli, is a prolific poet, scholar, and political activist and a leader of the Hawaiian sovereignty movement. She is the author of two scholarly monographs, Eros and Power: The Promise of Feminist Theory (1984) and From a Native Daughter: Colonialism and Sovereignty in Hawaiʻi (1993), a foundational text in Hawaiian and Indigenous studies, and has written many influential essays. She has two poetry books, Light in the Crevice Never Seen (1999) and Night Is a Sharkskin Drum (2002). She is a professor emeritus of Hawaiian studies at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, where she cofounded the Kamakakūokalani Center for Hawaiian Studies.

HAUNANI-KAY TRASK (1949–), Kanaka Maoli, is a prolific poet, scholar, and political activist and a leader of the Hawaiian sovereignty movement. She is the author of two scholarly monographs, Eros and Power: The Promise of Feminist Theory (1984) and From a Native Daughter: Colonialism and Sovereignty in Hawaiʻi (1993), a foundational text in Hawaiian and Indigenous studies, and has written many influential essays. She has two poetry books, Light in the Crevice Never Seen (1999) and Night Is a Sharkskin Drum (2002). She is a professor emeritus of Hawaiian studies at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, where she cofounded the Kamakakūokalani Center for Hawaiian Studies.

there is always this sense:

a wash of earth

rain, palm light falling

across ironwood

sands, fine and blowing

to an ancient sea

i hear them always:

with fish hooks and nets

dark, long

red canoes

gliding thoughtlessly

to sea

and the still lush hills

of laughter

buried in secret

caves, bones of love

and ritual, and sacred

life

a place for the manō

the pueo, the ‘ōʻō

for the smooth flat pōhaku

for a calabash of stars

flung over the Pacific

and yet

our love suffers

with a heritage

of beauty

in a land of tears

where our people

go blindly

servants of another

race, a culture of machines

grinding vision

from the eye, thought

from the hand

until a tight silence

descends

wildly in place

Night is a sharkskin drum

sounding our bodies black

and gold.

All is aflame

the uplands a shush

of wind.

From Halema‘uma‘u

our fiery Akua comes:

E Pele ē,

E Pele ē,

E Pele ē.

I ride those ridge backs

down each narrow

cliff red hills

and birdsong in my

head gold dust

on my face nothing

whispers but the trees

mountains blue beyond

my sight pools of

icy water at my feet

this earth glows the color

of my skin sunburnt

natives didn’t fly

from far away

but sprouted whole through

velvet taro in the sweet mud

of this ‘āina

their ancient name

is kept my piko

safely sleeps

famous rains

flood down

in tears

I know these hills

my lovers chant them

late at night

owls swoop

to touch me:

‘aumākua

EARLE THOMPSON (1950–2006), Yakima, was born in Nespelem, Washington. His creative works have won writing competitions, such as the one held at Seattle’s annual Bumbershoot festival, and they have been included in various publications, including Blue Cloud Quarterly.

EARLE THOMPSON (1950–2006), Yakima, was born in Nespelem, Washington. His creative works have won writing competitions, such as the one held at Seattle’s annual Bumbershoot festival, and they have been included in various publications, including Blue Cloud Quarterly.

My grandfather placed wood

in the pot-bellied stove

and sat; he spoke:

“One time your uncle and me

seen some stick-indians

driving in the mountains

they moved alongside

the car and watched us

look at them

they had long black hair

down their backs and were naked

they ran past us.”

Grandfather shifted

his weight in the chair.

He explained,

“Stick-indians are powerful people

they come out during the fall.

They will trick little children

who don’t listen

into the woods

and can imitate anything

so you should learn

about them.”

Grandfather poured himself

some coffee and continued:

“At night you should put tobacco

out for them

and whatever food you got

just give them some

’cause stick-indians

can be vengeful

for people making fun of them.

They can walk through walls

and will stick a salmon up your ass

for laughing at them

this will not happen if you understand

and respect them.”

My cousin giggled. I listened and remember

Grandfather slowly sipped his coffee

and smiled at us.

The fire smoldered like a volcano

and crackled.

We finally went to bed. I dreamt

of the mountains and now

I understand my childhood.

DIAN MILLION (1950–), Tanana Athabascan, received her PhD from the University of California, Berkeley. Million’s Therapeutic Nations: Healing in an Age of Indigenous Human Rights focuses on the politics of mental and physical health, with attention to how it informs race, class, and gender in Indian Country. She teaches American Indian Studies at the University of Washington.

DIAN MILLION (1950–), Tanana Athabascan, received her PhD from the University of California, Berkeley. Million’s Therapeutic Nations: Healing in an Age of Indigenous Human Rights focuses on the politics of mental and physical health, with attention to how it informs race, class, and gender in Indian Country. She teaches American Indian Studies at the University of Washington.

Minnie had a house

which had trees in the yard

and lots of flowers

she especially liked the kitchen

because it had a large old cast iron stove

and that

the landlord said

was the reason

the house was so cheap.

Pretty soon Minnie’s brother Rupert came along

and his wife Onna

and they set up housekeeping in the living room

on the fold-out couch,

so the house warmed and rocked

and sang because Minnie and Rupert laughed a lot.

Pretty soon their mom Elsie came to live with them too

because she liked being with the laughing young people

and she knew how the stove worked the best.

Minnie gave up her bed and slept on a cot.

Well pretty soon

Dar and Shar their cousins came to town looking for work.

They were twins

the pride of Elsie’s sister Jo

and boy could those girls sing. They pitched a tent under

the cedar patch in the yard

and could be heard singing around the house

mixtures of old Indian tunes and country western.

When it was winter

Elsie worried

about her mother Sarah

who was still living by herself in Moose Glen back home.

Elsie went in the car with Dar and Shar and Minnie and Rupert and got her.

They all missed her anyway and her funny stories.

She didn’t have any teeth

so she dipped all chewable items in grease

which is how they’re tasty she said.

She sat in a chair in front of the stove usually

or would cook up a big pot of something for the others.

By and by Rupert and Onna had a baby who they named Lester,

or nicknamed Bumper, and they were glad that Elsie and Sarah

were there to help.

One night the landlord came by

to fix the leak in the bathroom pipe

and was surprised to find Minnie, Rupert and Onna, Sarah and Elsie, Shar and Dar

all singing around the drum next to the big stove in the kitchen

and even a baby named Lester who smiled waving a big greasy piece of dried fish.

He was disturbed

he went to court to evict them

he said the house was designed for single-family occupancy

which surprised the family

because that’s what they thought they were.

GLORIA BIRD (1951–), Spokane, is a poet and a scholar whose honors include the Diane Decorah Memorial Poetry Award from the Native Writers’ Circle of the Americas. Her work frequently discusses and works against the harmful representations and stereotypes of Native peoples. As one of the central figures of Northwest Native poetry, Bird taught at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe and was a cofounder of the Northwest Native American Writers’ Association.

GLORIA BIRD (1951–), Spokane, is a poet and a scholar whose honors include the Diane Decorah Memorial Poetry Award from the Native Writers’ Circle of the Americas. Her work frequently discusses and works against the harmful representations and stereotypes of Native peoples. As one of the central figures of Northwest Native poetry, Bird taught at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe and was a cofounder of the Northwest Native American Writers’ Association.

The one-room adobe skeleton sat on a hill overlooking a field that would not grow anything but adobe brick. We packed holes around the vigas in winter, built a fire to “sweat” the walls insulating us for moving in.

Sr. Lujan sold the land as dried and Mexican as he, would sell what lay on the land: the rusted equipment of his father, the cellar dug into the dirt, and the bridge we crossed to reach the land he’s sold.

His fat lawyer spoke with hands as coarse and brown as burnt fish asking for the price of the bridge belonging to Sr. Lujan, one hundred dollars to not be bothered any longer, Sr. Lujan whispering, “es verdad” next to him.

In Chimayo a crucifix is planted higher up on a ridge watching over what sacrifices were made of Chimayo all year. From my knees, I watched brighter stars journey the path of sky the cross did not fill through the night of my labor, rocking for comfort not found through an open window.

Early morning I lay on the floor to give birth, a veil of rain falling. Hina-tee-yea is what he called it in his elemental language. Four days later, named our daughter also, fine rain, child of the desert mesas, yucca, and chamisal.

Across the arroyo, the news would remind Manuelita of her grief, y su hijito lost the month we moved in. That spring, centipedes sprinkled sand from the warming vigas where they were hidden.

Your absence has left me only fragments of a summer’s run

on a night like this, fanning in August heat, a seaweeded song.

Sweat glistens on my skin, wears me translucent, sharp as scales.

The sun wallowing its giant roe beats my eyes back red and dry.

Have you seen it above the highway ruling you like planets?

Behind you, evening is Columbian, slips dark arms

around the knot of distance that means nothing

to salmon or slim desiring. Sweet man of rivers,

the blood of fishermen and women will drive you back again,

appointed places set in motion like seasons. We are like salmon

swimming against the mutation of current to find

our heartbroken way home again, weight of red eggs and need.

ELIZABETH “SISTER GOODWIN” HOPE (1951–1997), Iñupiaq, served on the Institute of Alaska Native Arts board and was a member of the Native American Writers’ Circle of Alaska. She was married to Tlingit poet Andrew Hope III. She published a book of poems called A Lagoon Is in My Backyard in 1984.

ELIZABETH “SISTER GOODWIN” HOPE (1951–1997), Iñupiaq, served on the Institute of Alaska Native Arts board and was a member of the Native American Writers’ Circle of Alaska. She was married to Tlingit poet Andrew Hope III. She published a book of poems called A Lagoon Is in My Backyard in 1984.

when popcorn

first came up north

north to Kotzebue sound

little iñuit

took it home from school

long long ago when

the new century first woke up

Aana sat on neat

rows of willow branches

braiding sinew into thread

Uva Aana niggin

una piksinñaq

for you grandmother

eat this

it is something that bounces

after Aana ate it

the little iñuit girls

giggled hysterically

for sure now, they said

old Aana is going to bounce too

for hours

Aana sat hunched over

with her eyes squinched shut

she grasped onto neat rows

of willow branches

waiting for the popcorn

to make her bounce around

DAN TAULAPAPA MCMULLIN (1953–), Samoan (Amerika Sāmoa), a faʻafafine poet, visual artist, and filmmaker, was raised on Tutuila Island in the villages of Maleola and Leone. He has garnered national acclaim, receiving awards like the Poets & Writers Award from the Writers Loft and earning a spot on the American Library Association Rainbow Top Ten List. Along with his poetry, his visual artwork has been exhibited worldwide, including at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, New York University’s Asian/Pacific/American Institute, and the United Nations.

DAN TAULAPAPA MCMULLIN (1953–), Samoan (Amerika Sāmoa), a faʻafafine poet, visual artist, and filmmaker, was raised on Tutuila Island in the villages of Maleola and Leone. He has garnered national acclaim, receiving awards like the Poets & Writers Award from the Writers Loft and earning a spot on the American Library Association Rainbow Top Ten List. Along with his poetry, his visual artwork has been exhibited worldwide, including at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, New York University’s Asian/Pacific/American Institute, and the United Nations.

There was a ship

went into the sea

over the body of my brother

I am just a boy

he was not much older than me

the goddess is good and cruel

wants her share of life, like us

sparkling dust of birds far away whom we follow, the stars

the blood red dust of life

as my brother’s face

disappeared beneath us

beneath the ship which carried us and the goddess

to where we do not know

leaving the war of my grandfather

the smell of smoke following us

our keel, my brother, knocking down the doors of the sea

the tall, and the wild waves coming, crashing

under the keel of my brother’s name

far from the sound of places we were leaving

the roads we followed

marching past my uncle’s crooked mountain forts

while his men called out at us

with our long hair

on our shoulders

first by my brother’s name

who was this girl with him, leave her with us

she is my brother, he said

not glancing at me

our songs we sang in the warm rain for the goddess

blessed be her name

her cloak the wild wood pigeons turning

her crown the lone plover’s crying

where now are you brother?

JOE BALAZ (1953–), Kanaka Maoli, is a poet in both American English and Pidgin (Hawaiian Creole English) and an editor. Invested in preserving Hawaiian oral traditions as well as Pidgin writing, Balaz wrote After the Drought (1985), and OLA (1996), a collection of visual poetry; edited Hoʻomānoa: An Anthology of Contemporary Hawaiian Literature (1989); and recorded an album of Pidgin poetry, Electric Laulau (1998). In 2019 he published Pidgin Eye, a collection of poems written over the previous thirty years.

JOE BALAZ (1953–), Kanaka Maoli, is a poet in both American English and Pidgin (Hawaiian Creole English) and an editor. Invested in preserving Hawaiian oral traditions as well as Pidgin writing, Balaz wrote After the Drought (1985), and OLA (1996), a collection of visual poetry; edited Hoʻomānoa: An Anthology of Contemporary Hawaiian Literature (1989); and recorded an album of Pidgin poetry, Electric Laulau (1998). In 2019 he published Pidgin Eye, a collection of poems written over the previous thirty years.

Charlene

wun wahine wit wun glass eye

studied da bottom

of wun wooden poi bowl

placed in wun bathtub

to float just like wun boat.

Wun mysterious periscope

rising from wun giant menacing fish

appeared upon da scene.

Undahneath da surface

deeper den wun sigh

its huge body

lingered dangerously near da drain.

Wun torpedo laden scream

exploded in da depths

induced by Charlene

who wuz chanting

to da electric moon

stuck up on da ceiling.

Silver scales

wobbled like drunken sailors

and fell into da blue.

No can allow

to move da trip lever on da plunger

no can empty da ocean

no can reveal da dry porcelain ring

to someday be scrubbed clean.

Charlene

looked at all da ancestral lines

ingrained on da bottom of da round canoe

floating on da watah

and she saw her past and future.

Wun curious ear wuz listening

through wun empty glass

placed against da wall

and discovered

dat old songs wuz still being sung

echoing like sonar