No occupation is so delightful to me as the culture of the earth, and no culture comparable to that of a garden.

—Thomas Jefferson

OUR DEEPEST CONNECTION TO THE earth is usually through the plant world. They provide for us in so many ways. They are the substance of life. They have the amazing ability to reach to the skies and collect energy from the sun and transform it into food for animals and insects without which we could not survive. They nurture our bodies as they nurture our souls. The earth smiles with their flowers while providing an ocean of oxygen for us to breathe. They are the delicate essence of the beauty of life. They are the best recycler of water and soil.

To work in a world surrounded by plants is a beautiful place to be. I love my relationship with them and learn a little more about them every day. People often think one gets into this because plants are so easy to work with. It tells something of the personality of gardeners. If the plants are not happy, they just die. Yet they have an incredible will to live. The relationship between plants and gardeners is a special one. Plants are very sensitive and invite intimacy. This is where the soul of the gardener meets the soul of the plant world. They open us up to a special part of the universe that is subtle, yet grand.

Plants are also great teachers, just as children are. They provide an environment that feeds me spiritually. Growing plants is both a science and an art that interacts with all humans on a daily basis. Each plant family has its own way of taking form and utilizing the resources from above and below the ground.

The cactus is an interesting example. Its entire above-ground surface can photosynthesize the sun’s rays—it collects the energy from 360 degrees. It has a vast root system that can travel hundreds of yards. So when it does rain in the desert, it does not miss a drop. It also stores water incredibly well for long dry periods.

Plants have distinct smells, tastes, and textures for interacting with nature. Establishing a garden with some blind gardeners offered me insight into how to communicate with plants. These gardeners taught me how to experience communication with my eyes closed. This can be used as a teaching tool for children’s gardens. Plants are very diverse and work well in a diverse environment. As a garden or farm evolves, so does the environment around it and throughout it. Plants help create their environment as they interact with nature. Plants are the best indicators of what works well in your given area. Each area has its own unique set of dynamics.

As our planet has gotten smaller, so have the unique varieties of each area. I have seen nonnatives strewn across the global landscape. Some are very invasive. You can find lantana in Indonesia, Acacia longifolia in Brazil, scotch broom in California, and water hyacinth all over the tropics. In Georgia, we have the wonderful kudzu plant that was brought here to check erosion on the land that was being cotton farmed to death. One of my first jobs in Georgia was working with the county cooperative extension service. I found some old pamphlets in the back storeroom promoting kudzu as something every family should be planting, but I was told we would not be giving those out. They dated back to the 1950s. Standing on the hillside in Georgia, it is amazing to think that hundreds of years ago we would be standing ten feet higher, before the land eroded into the Gulf of Mexico or the Atlantic Ocean depending on which way the creeks flowed.

During the process of growing heirloom plant varieties and collecting the seed from them, it is good to recognize where they are from. There may be Italian beans and garlic, Russian tomatoes and kale, or New Mexican chiles and hot peppers. This is a little strange when you consider that beans are from North America and tomatoes and peppers are from South America. These seeds have traveled and would have wonderful stories if they could talk.

I have lineage from most European countries; I guess we all have a little hybrid vigor in us. When using seeds from season to season they become more adapted to their own microenvironment. It is easy in a kitchen garden to become somewhat attached to your garlic varieties, tomatoes, melons, and so on. Or to feel a sense of ownership for cleomes, nigella, or larkspurs, as they become a part of a place. Yet do we really own them or are we just borrowing them as they pass through our hands? Seeds are nothing more than a gift from nature. I save many of my seeds and they acclimate to my garden. Yet each season comes and goes. The garden exists for that season and those seeds do also. It is the idea of expressing yourself in your work. So it really comes down to lifestyle and perspective. This is part of the connection with plant culture.

As we become set in our ways, we savor and hold on to things like seeds. The plants take on certain characteristics that make them desirable. Seeing plants as more than just what they offer as food gives us a different appreciation of their being. Flowers can be beautiful and magical regardless of size. The national flower of Belize is a tiny black orchid and it is just as beautiful as any found in Malaysia. A cauliflower is a rich floribunda that is a grand sight to behold.

Flowers are the messengers of the genetic makeup of the plant. Each one is exquisite with its own unique form. As people have traveled around the world so have the seeds and plants of their homeland. I enjoy the stories that followed their linage. But I am not an anthropologist. The work I do in horticulture and agriculture is justified in just doing it. As a grower one would be more interested in the plants’ traits that serve them, like how well they produce, disease resistance, storage of roots and fruits, and, of course, the taste, smells, and textures that I learned about from my blind gardener friends.

Plants’ physical nature is an efficient system of capturing and storing energy that becomes food for them and us. As a seed germinates, it forms first a radical; then it forms a hypocotyl, cotyledons, plumule, and root hairs. Until this takes place, it is relying on stored food in the seed itself. Visualize the plant upside down to understand its growing trait. Lateral roots stabilize the plant as the root tip continues growing into new territory. The root tip maintains constant cell growth due to abrasion with the soil it is traveling through and because this is where the new growth takes place. This is the meristematic region at the root tip. The apical hormone relates to plant growth and is a crucial messenger. The further down it grows, the further a plant grows up toward the sun.

The interaction with the soil involves a series of symbiotic relationships primarily with the root hairs. Roots absorb nutrients through epidermal cells. Yet root hairs are responsible for most absorption of water and nutrients. They are short-lived and regenerate quickly. Root hairs are most vulnerable to damage during transplanting. Loss of them sets the plant growth back. This is why it is best to minimize their damage. Woody stem plants are best planted during their dormant stage for this reason. They do not regenerate as quickly. Besides the adsorption of water, several chemical and biological interactions occur. Root exudates attract beneficial components and repel undesirables. Of course, this does not always work or there would not be disease and insect problems. A good example of repelling is French marigolds and African black oats that are effective in warding off root knot nematodes. Other root exudates attract rhizobial activity and beneficial bacteria like actinomycetes, azobacters, azohizobium, and other beneficial bacillus forms. This symbiotic relationship is important for healthy soil plant relationships, for the soil is the intestines of the plant world. The flora and fauna produce soluble nutrients from organic matter in a form that roots can assimilate. Fungal threads, called hypae, form a cover around roots and sometimes penetrate the root itself. This is important for the plant’s growth. If you introduce salt-based fertilizers, like 10-10-10, the salts and other synthetic ingredients are toxic. They inhibit and actually destroy these biological life forms. What you are doing is creating a dependency on synthetic chemical-based fertilizer because you have essentially killed off the natural order for doing this. It really comes down to short-term gain versus the long-term development of your soil.

Plant nutrition is important in understanding how plants function. As nutrients are absorbed they travel upward through the xylem, out through the petiole, and into the leaf. The xylem provides a channel for water and the nutrients absorbed in it. The leaf contains chloroplasts that help manufacture food from sunlight. Stomata cells located on the bottom allow the leaf to breath and release water during hot days (referred to as transpiration). These also work as guard cells to protect the size of what comes in. Foliar feeds work by spraying solutions that can be absorbed this way. Plants produce carbohydrates that are sugars in the leaf. These sugars are sent to other parts of the plants as needed. This is called translocation. It is sent down through the phloem. The excess food is stored mainly in the roots.

Of course, the whole process is much more complex than this. There are many nutrients that play vital roles in photosynthesis. The least of which is molybdenum along with chlorine, zinc, iron, manganese, copper, magnesium, and nitrogen. About 18 percent of the protein of the plant is made up of nitrogen. It is important as a protein builder and stimulates chlorophyll and green growth. Stem and leaf growth depends on it. It also is necessary for the formation of growth hormones. Nitrogen deficiency is indicated by yellowing of older leaves and overall stunted growth. Too much nitrogen causes a buildup of amino acids in plant tissue. The plant becomes more susceptible to plant diseases. This is the nutrient that most often needs to be replenished. It is used up quickly during the growing season. Legumes used as cover crops and composted manure, both animal and green manure, are a good source of nitrogen.

Phosphorous has the main role of facilitating energy metabolism. It plays a role in cell development. Again, compost and cover crops provide the best source of phosphorous and potassium. Phosphorus also stimulates flowering activity and seed germination. It is important for photosynthesis, protein formation, and energy metabolism of the plant. It forms bonds against bacterial diseases. A primary source of phosphorus is bone meal. Rock phosphate is another source, but not a sustainable one. It comes from mines. Deficiencies show up as purple stems, leaves, and flower drop.

Potassium is an activator of many enzymes. It aids in the formation of sugars, starches, proteins, and carbohydrates. It helps with cell division and activates various enzymes. It is necessary for protein synthesis. It also stimulates strong stems and roots. If you live in a place of granite, then you have access to granite sand and can cycle it through the compost pile or sometimes put it directly in the soil. Mottled, spotted, curled, or scorched leaves and burnt leaf margins and tips indicate potassium mineral deficiencies. It can show up as a temporary condition on young plants.

Sulfur is also a builder of proteins and amino enzymes. It aids in chlorophyll production and is more available in areas of high rainfall. Rainfall contributes to hydrogen. This correlates to a more acid soil or lower pH (probable hydrogen). Arid areas can suffer from a lack of sulfur. Deficiencies are similar to nitrogen deficiency with light green leaves.

Calcium helps build cell walls. So it is important to all parts of plant growth, especially roots. It supports water movement in the xylem and helps facilitate the uptake of nitrogen. Deficiencies include yellow leaf margins. Calcium and boron deficiencies contribute to excess sugars and amino acid buildup in the leaf and stem. Fungal diseases release enzymes that dissolve the lamella that bonds cells together. Calcium inhibits this activity. It forms bonds against bacterial disease. Calcium is not available in low pH soils, so liming is the best solution. The calcium is tied up at a low pH. Deficiencies can cause flower and fruit to not mature properly; this is known as blossom end rot.

Magnesium is an activator of chlorophyll. It also produces many enzymes and aids in phosphate transfer and enzymes for carbohydrates. It helps sugar and fruit production development and seed germination. It is usually readily available in a mineral balanced soil. If you need to add lime to the soil to raise the pH, use dolomitic limestone to incorporate the magnesium.

Next are the micronutrients; they are generally readily available in most soils. Iron is a catalyst for chlorophyll. It is necessary for photosynthesis and stimulates new growth and respiration. It shows deficiency through yellowing between the veins of leaves (chlorosis).

Manganese activates enzymes for photosynthesis. It helps chloroplasts function. It aids in the metabolism and respiration of the plant. It also aids in the metabolism of nitrogen.

Boron contributes to calcium uptake, the translocation of sugars, movement of hormones, and the formation of pollen. Deficiencies show up as brittle stems and leaves, hollow heart in potatoes. Boron also helps produce defense compounds. Borax can be a quick fix for boron when needed.

Silica helps protect leaves from fungal penetration. It is used widely in biodynamic preparations, in both 501 (the horn silica) and 507 (horsetail herb tea). Silica can be produced by using grasses, such as rye, oats, or wheat as a cover crop. I use a lot of bamboo for trellising beans, tomatoes, peppers, and eggplant. When the bamboo starts to crack it goes into a burn pile. The ash is used in composting as a source of silica.

Copper aids in the metabolism of enzymes for proteins and carbohydrate production. It supports photosynthesis. Deficiencies cause dye back of shoot tips.

Zinc plays a role in auxin hormones. Auxin hormones affect the direction of growth in the plant and are located at the growth tips. Zinc is another component of photosynthesis. Zinc activates and metabolizes amino acids. If deficient, it can cause little leaf or rosetting. This inhibits the internodes to grow properly. If you prune side shoots, it stimulates auxin hormones to grow upward. Pruning the top of the plant also stimulates horizontal growth.

Molybdenum is the smallest nutrient found in plants. It helps break down ammonia and is essential to photosynthesis. Deficiencies affect nitrogen uptake in the plant.

Chlorine is necessary for osmosis and water transport in the plant cells. It is rarely deficient. Nickel helps break down urea. Nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, sulfur, and magnesium are macronutrients. All others are micronutrients.

It is best not to add or try to adjust micronutrients. They are needed in minute amounts. Adding them can be antagonistic to other nutrients. Excess copper or sulfur may affect molybdenum uptake. Excess zinc, manganese, or copper affects iron uptake. Excess phosphorus can cause a zinc, copper, or iron deficiency. Excess potassium affects manganese uptake. Excess iron, copper, or zinc also affects manganese absorption. So you see, it gets rather tricky to be a soil chemist and farmer at the same time. If you are feeding the soil a balanced mixture of life-giving properties as found in rich compost that is fully decomposed, it will provide a plentiful variety of nutrients. Seaweed is another source of micronutrients. Beyond that, the microorganisms in humus digest all the nutrients that the plants need. A balanced source rich in humus works best.

Most of the plants grown in the garden or farm are angiosperms. They contain built-in ovaries where seeds develop. Gymnosperms produce seeds on the outside. Pines are an example of this. Plant families make it easier to understand their individual needs. Phaseolus vulgaris, such as beans, and its relatives, peas, clover, peanuts, lentils, and related legumes, are nitrogen builders. They actually absorb nitrogen from the atmosphere and fix it. The nitrogen nodules can be found on their roots. They are native to North America. These plants are givers and help build up the soil; they will grow in many conditions. They tolerate some shade, but prefer sun and a neutral pH.

Asparagus officinalis is not related to other plants commonly grown for food. It originated from the western part of Europe. It is a coastal plant so it tolerates salt air quite well. It likes a bit more of an alkaline soil, pH 7–7.5, and grows along a rhizobial pattern with strong root development. It functions well where there is a lot of fungal growth. Plant it in a permanent location. If cared for it can last for several years.

Beta vulgaris (beets) are in the family of Chenopodium along with spinach, chard, lamb’s-quarter, and quinoa. They are medium to heavy feeders on the soil. They are a European native that likes a rich loamy soil and neutral pH.

Crucifers are a large group of vegetables. Brassicas are a subgroup. The Brassicas can be broken down into many species. The Europeans took cabbage and developed it into broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cauliflower, kale, kohlrabi, and the like. The Chinese took crucifers (the main group) that include mustards and developed them into bok choi, tat choi, mizuna, Chinese cabbage, and several others. The third group of Cruciferae includes turnip, radish, and rutabaga. These are cool weather crops. They are heavy feeders on the soil and need potassium. The leafy ones, like cabbage and broccoli, need lots of nitrogen.

Apiaceae or Umbelliferae are easy to identify by their flowers. This group consists of carrots, parsley, cilantro, dill, parsnips, celery, caraway, anise, lovage, fennel, cumin, angelica, and anything with a similar flower. They are native to southern Europe and enjoy cool dry conditions, very loamy soil, a neutral pH, but they will tolerate some fluctuation in soil types.

Cucurbitaceae belong to the squash family. They produce both male and female flowers on the same plant. If the soil is too acid, they cannot take up needed calcium and suffer from blossom end rot on their fruit. The subgroups are divided into four groups: melons, cucumbers, summer squash, and winter squash.

Zea mays is another vegetable from the Americas. Its common name is corn. Corn has an interesting history traced back to the Incas. It is not totally clear just what or where it came into play. It requires human interaction since seeds need to be planted and they do not store well. It is also a monocotyledon. This means it sends up one leaf and then an alternate leaf, like grass or bamboo. Dicotyledons produce two leaves at a time, opposite one another. Corn needs to be planted in a series of rows in order to pollinate well. If not planted in consistent rows, the ears end up with jack o’lantern smiles with half their kernels missing. Most of the plants in the garden are dicotyledons, sending out two leaves at a time. The dicotyledons fall off once the first true leaves take form.

Alliums consist of onions, garlic, shallots, and leeks. They are also mono cots. They have been traced back to Africa, southern Europe, and South America. They like a loamy or even sandy soil with good drainage. They respond well to a soil rich in potassium.

Solanaceae is the most popular family consisting of tomato, pepper, eggplant, potato, and tobacco. It is also related to deadly nightshade. It is native to the Andes mountain region of South America. There are occasional new discoveries of potatoes being dug up to turn into a new garden variety. Although potatoes like an acid soil, the others like a neutral pH. They respond well to a rich soil; the better the soil the better they produce. They are fairly heavy feeders.

Lactuca sativa (lettuce) has been developed into many varieties since Egyptians first developed it. It is in the Aster family like sunflowers and all types of daisy. The seeds are formed in the middle of the flower. It is a light feeder, fond of cool weather, and can accept some shade.

Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) is from west Africa and south Asia. It does well in heat. People often ask, when is it time to plant okra? I tell them when you start sweating. It is a heavy feeder. It is in the hibiscus family and related to mallow plants like hibiscus, hollyhock, and cotton.

Sweet potato is often mistaken for a type of potato. It is not at all related to the Solanaceae family. It is related to morning glory. It does well in poor soils that are cultivated well. Understanding these groups will help you to know what to plant where, and how the plants will interact with one another.

All plant families have unique ways of dealing with their environment and have physical traits for doing so. Leaf structure is a good example of this. Hairy leaves are used for insulation from light frosts. They reduce evaporation and collect moisture. They also protect against some insects. Waxy leaf plants are covered with a coating of lignin that protects against some diseases and insects. Cactus is obviously very protective about who it lets get close.

Plants relate to their environment in a number of ways. Plants can communicate with other plants as well. Researchers at the University of Aberdeen, Scotland, have discovered ways in which plants communicate by sending signals along different channels. First, damaged plants give off odorous chemicals, referred to as volatile organic compounds, that repel insect damage. Secondly, plants use the filaments or hyphae of mychorrhizal fungi to relay messages of danger. Plants also give off vibration patterns to attract bees.

The energy plants put out is very subtle. They are very sensitive to their surroundings. Plants are integral to their environment; they play a role in what is going on around them. Without their presence the environment is altered. Plants like growing in a space surrounded by other plants. They don’t like being too crowded to inhibit their growth, but like to be in close proximity with one another.

Understanding this level of sensitivity is important in knowing how to communicate with plants. Handling them in a gentle manner is a good place to start. Young plants are as gentle as their roots. You are a vital part of their environment. As you nurture the growth of the plants, you are sending them positive energy. To enhance the growth of the entire piece of land is to enhance each plant contained in it. They are gracious in their growth. Direct contact with them is something that they respond favorably to. Checking plants for insects and diseases is a form of grooming them. The attention they receive is nurturing to them. As they reach to the sky they also fill the space that they’ve been given. Most plants we grow are cultivars, derived from their wild cousins. They will need a boost to compete in the wild environment they have been cast out in. Understanding the growth habits of these species will help you prepare for their development into maturity.

The relationships and disrelationships between plants encourage healthy growth patterns. Plants that reflect similar needs can share similar habitats. Plants that support each other’s growth habits are a good choice. Plants with long taproots such as lamb’s-quarter, dock, or alfalfa are very good at permeating hard soil. Those cultivators help bring needed nutrients to the surface for shallow-rooted plants. Nitrogen fixers offer nutrients for heavy feeders like spinach, cabbage, or corn. Plants that exude strong aromas like garlic or herbs offer a deterrent for plants susceptible to insect damage.

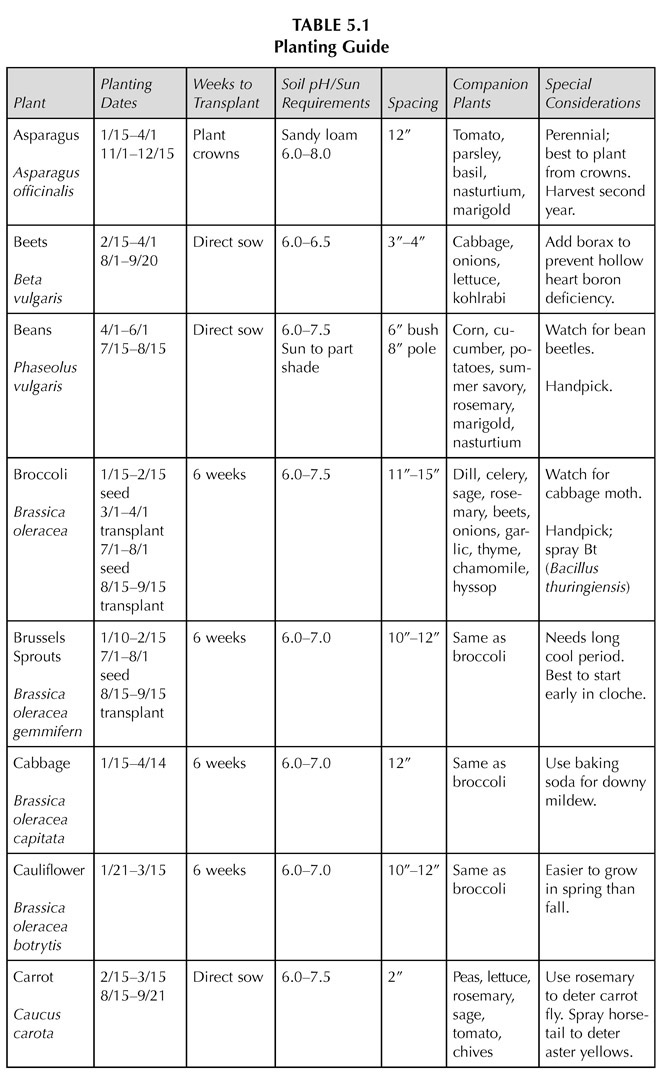

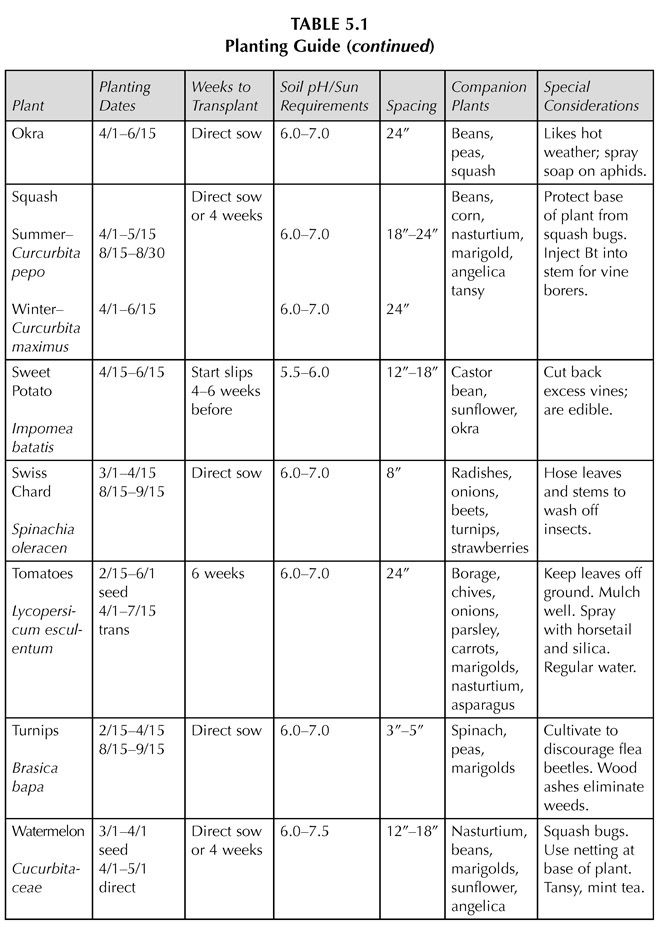

In planning a garden there are many considerations to take into account. Timing of planting is one of these. (The dates used in planting guides are for zone 7b. Add or subtract one to two weeks for each zone accordingly.) Efficiency for the work ahead is another factor. Prevention also needs to be part of the plan. There are other factors to consider like the health of the soil, weather, and so on.

There are various techniques for starting seeds successfully based on their needs. Root crops need to be sown directly into the soil. Since they are primarily roots, you don’t want to disturb that part of the plant too much. Broadcast carrots, beets, and radish onto a finely prepared bed. The art of laying them down so that there is minimal thinning later takes a bit of skill and practice. It is easy to oversow the seed. Carrots and radishes need a couple inches, beets a few inches or more. Then, spread a one-half-inch cover of spent compost or leaf mold.

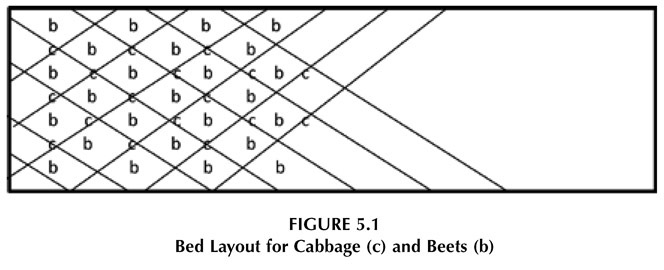

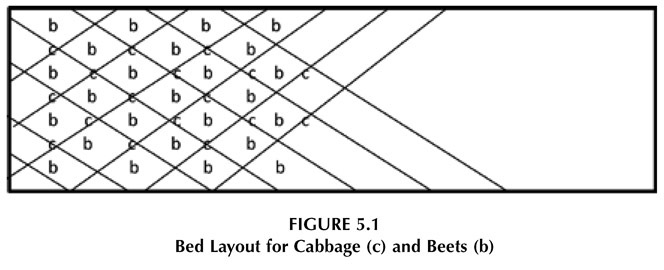

Because of the mild winters in the south, you can plant carrots in early October. They get established in the fall, brave the winter, and provide me with mid-spring carrots that are usually delightful. You can plant turnips in drills. Make light impressions in the soil a few inches apart in staggered rows across the bed and drop a couple seeds in each space and lightly cover. It is easier to keep track of them. A light water with a rose flare a few times a day helps ensure germination. Peas, beans, and other legumes are poked directly into the soil, as are corn and all cucurbits (the squash family). Using a zigzag method down the bed helps fill the squash bed well once the plants mature. A staggered planting is an optimum use of space that would otherwise invite weeds. The weeds will move in during the early phase of bed development, but once the plants mature there will be little space for them. Figure 5.1 illustrates a bed layout for cabbage and beets.

Many of the easy flowers, like marigolds, celosia, zinnias, cosmos, cleome, and sunflowers are easy to direct sow. Larkspur, nigella, and poppies can be sown during the winter. The winter cold triggers them with what they need biologically. In nature, they drop seeds in the fall. After a series of frost, they know when it is time to come up. You can do this artificially by putting them in the freezer to get the same effect.

Many other families are too fragile and need to be started indoors, namely, the brassicas (cabbage family), with exception to kale and collards, and Solanaceae (tomatoes, peppers, eggplant). Lettuce, spinach, and mustards (Chinese greens) can be directly sown or started indoors. It is preferred to start them as transplants to get an earlier start and prevent loss. It is easy to broadcast kale and collards. Thinning them later provides one with several harvests at various stages of growth. You may wish to start some kale as transplants and direct sow some. It offers a variety that works here.

Perennial flowers are peculiar and often difficult to grow. Many require being planted on the surface of the potting soil and watered with a fine mist. It is good to freeze the seed for 48 hours to trick them into germination after a winter chill. The bag method helps them to germinate. This is discussed in the chapter on propagation (chapter 6). Delphiniums require darkness for germination. Most alliums are started indoors and transplanted with a dibble. You can make one from a hardwood branch.

Garlic is the exception. These are best planted in the fall in my area. Alliums do not do a good job of covering the bed to keep weeds out like other plants. A lot of mulch and diligent weeding is required. Garlic is a high maintenance plant that responds well to the care I give it. Herbs are often easier to grow if annual or biennial. Many of the umbellifers will reseed themselves and come up the following spring. Dill, cilantro, and parsley are good at this. They often reseed themselves, which produces volunteers for the next season. These volunteers are good for providing extra plants that can be moved into empty spaces in beds.

Caring for plants properly brings the same results as caring for anything that is alive. The stages of growth in plants require different amounts of attention. From seedlings to transplant is a fragile time. Plants are tender, yet vigorous. The delicate new life has an excitement and vitality of life about it. They are easy to impact and more sensitive to climate and their environment. This is a time when fertilizing will have the biggest impact. It is also easier to overfertilize; weekly supplements especially during a waxing moon bring desired results.

Fish emulsion, compost, or comfrey tea diluted is good. As plants are developing into maturity, they can and should be in their optimum health. An established nutrient base is most effective now. This is where you see the effects of soil preparation and proper irrigation. New growth is important for the plant to become well established. It is time to train and help the plant create the environment that supports healthy growth.

Once the plant reaches maturity, it moves into the reproductive phase. The shift in energy is toward procreation more than growth. All living things want to reproduce; that is their objective. Seed production is where they are headed. It is easier to see this in annuals. For them, it is one season, one big fast performance. Perennials are less in a hurry and focused more on adaptability. They move in the direction of affecting their environment. Whereas annuals are more affected by their environment, the energy of trees and shrubs has more of a relationship with wildlife, such as birds and small animals. Trees and shrubs can be used to establish boundaries and give definition to the surrounding area. The shift from short-term plantings to long-term ones is like moving from season to season rather than from month to month. They both have their place in the overall scheme of things.

It all begins with planting seeds. Plant seeds in flats at a depth of about twice their width into a mix of your own potting soil. One of the keys to growing from seed is to water often. You can’t put a lot of water into a seed. So they don’t need a lot of water at one time. Soil temperature is also important; above 70 degrees Fahrenheit is crucial for most seeds. Most seeds will come up in a week at this temperature. At 90 degrees, they will germinate in a few days. When they form the dicotyledons, they are susceptible to damping off fungus. You can deal with this by spraying Roman chamomile tea on the surface after watering. Damping off lives on the soil surface and the tea changes the soil chemistry, so it is not a conducive environment for damping off fungus to live in. Once plants grow their first set of true leaves, the damping off is no longer a threat. When plants develop their second set of true leaves, they are about ready for transplant. It is ideal for the plant to be at least four inches tall. See the planting guide in table 5.1.

Transplant into a well-prepared bed late in the day and keep the sun off the plant for a few days, depending on how much loss occurred to the root hairs. Roots hold water. Sun pulls water from the plant through respiration. So they need to grow new roots to deal with the sun. Water them well after transplanting and try to keep water off the leaves. Watering the leaves actually pulls water from the plant, and you don’t want this. Watering well around the base pulls soil in around the roots without forcing out air. A lot of people smash the soil around the plant. This is not favorable. Let the watering pull soil in around the roots. The roots need water and air and a place to grow that is soft, not a cement-like soil. Mulch helps keep the sun off the soil and water in the soil, as well as maintaining temperature in the soil. It helps to water the plants again in a few days if rain does not show up.

Successive plantings provide a continuous harvest. This is important for a market operation. This works better with some plants than others. It works well with the companion planting model. You can plant beans alongside cabbages that are almost ready for harvest to keep the space used well. Another method is to grow English peas in hoops; as they are finished, usually when it gets too hot for them, you can pull the peas and throw a shovel of compost in its place. This makes a nice place for a late crop of tomatoes.

As mentioned before, radishes mature as the lettuce leaves consume the bed space. An early planting of turnips comes out in time for a late planting of broccoli. Time can be a factor if trying to successive plant melons, winter squash, peppers, eggplant, garlic, onions, or sweet potatoes. Peas have a short window to grow here in the South. Try to use successive plantings as much as you can to ensure success. It can be a gamble with the weather, and it is easy to have losses trying to second guess what will work. This is especially true now with our very unpredictable weather patterns.

Caring for the plants helps keep them healthy. Once the plant has reached maturity, it should occupy the space well. There are generally some weeds that show up before the plants are full size. At this stage, pull weeds. By doing this you have cultivated the soil. Topdress the open soil with compost, water it well, and cover it with mulch.

The timing of weeding is a consideration and should be done a short while before the plant reaches full size. After this, if the bed is planted intensively, there will be no more room for weeds. This is referred to as the living mulch. Use staggered plantings across the bed. Plants are not square and do not fit into a grid. They are round and occupy round spaces well. Over the years I have moved away from straight rectangular beds. The bed layout should fill the needs of the plants, not the gardener.

Using a staggered planting allows many more plants for a given space. Here are the number of plants you get for a one hundred square foot bed. At 36" spacing, 20 plants (blueberries, blackberries, cardoon). At 24" spacing, 24 plants (tomatoes, melons, squash). At 18" spacing, 40 plants (peppers, eggplants potatoes, basil). At 12" spacing, 112 plants (cucumbers, small cabbage, broccoli, sunflowers, sweet potatoes). At 10" spacing, 144 plants (Chinese cabbage, cauliflower, several flower varieties). At 8" spacing, 200 plants (kale, Asian greens, chard, many flower varieties, celery). At 6" spacing, 345 plants (lettuce, beans, small Asian greens). At 5" spacing, 540 plants (garlic, small spinach, onions). Many small roots, such as carrots, beets, turnips, and radish are broadcast directly into beds and get 2" to 4" spacing depending on variety.

The mature leaves should just overlap enough to keep weeds out and protect the bed. Try to develop a canopy over the bed with the living mulch concept. This is part of the French intensive method. Weeds are really guardians of the soil. If you do not use an area well, they will—and preserve it for you until you are ready to use it. They demonstrate how to use land effectively. Their role is that of being the scar tissue of tilled land. They protect it and help put back the ecology that was destroyed. They become weeds until we discover a practical use for them.

Weeds are good indicators of the soil, as already mentioned in the first chapter. During drought conditions, weeds do a better job of protecting the soil until there is favorable weather you can work with. Of course, there are weeds, and then there are weeds. Plants like henbit (Lamium amplexicaule), Chinese mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris), purslane (Portulaca oleracea), lamb’s-quarter, violets, clover, plantain, and dandelion are quite welcome, as they are not very competitive plants. They are not only beneficial but also sometimes edible and medicinal. There are also plants that are very beneficial but might otherwise be considered weeds. Sonchus or sow thistle is an aid to tomato culture. This, along with fava beans used as a cover crop, can be dug into the beds where tomatoes are to be planted. Horsetail (Equisetum arvense) can be spread on top of the bed below the mulch as a disease preventative.

However, some weeds are not as pleasant to deal with. It is common to have a lot of Bermuda grass (Cynodon dactylon) and Johnson grass (Sorghum halepense); and occasionally pigweed (Amaranthus palmeri) is brought in accidentally. Pigweed is related to amaranth grain and callaloo, a popular green used in Jamaica and Belize cooking. It is hard to pick your weeds, just like it is hard to pick your neighbors. I learned a long time ago to work with what I’ve got.

I worked as an apprentice in Alan Chadwick’s Enchanted Garden at UC Santa Cruz, and later worked as an apprentice at Camp Joy Garden in the Santa Cruz Mountains. Both of these experiences fed me with a lot of inspiration. Plant culture is part of garden culture. The magic of the garden is no more than a human’s ability to understand nature. For it to be a full experience, it helps if it is done in complete cycles. This means from compost to harvest and back to compost, from seed planting to seed harvest. These gardens sustain themselves on what they grow as well as on the enthusiasm they create.

These gardens were the ultimate horticultural classroom, full of eager students. It was easy to learn a lot about methods and just as much about appreciating the work that was in front of me each day and for years to come. I would lie awake each night planting gardens in my mind. By the end of the season, they would blossom in my soul. As I formed the beds, they helped form me. All plants have a strong desire to grow. If you nurture them, they usually do quite well. If not, you will learn from them, for plants are also great teachers. The whole environment needs to work together. It is important to view it this way. The fruit trees are important to the garden beds below them. The birds and insects and all life forms are part of this holistic landscape, and you are the facilitator of this magical place.