REPETITIONS

144 For instance, since the second half of "Jingle Bells" (page 107) duplicates much of the first half, it obviously would save time and work if the repetition of the six measures (9 to 14) could be shown by a symbol, instead of being written out. This can be done as follows :

At the end of measure 8 you will observe a double bar with

two dots in front of it, like this

41

. This is a repeat

sign. It instructs you to go back to the beginning and play or sing the whole thing over again exactly as you did the first time. If the composer doesn't want to go all the way back to the beginning, he puts a similar sign, but facing

SUPPLEMENTARY SYMBOLS AND DEVICES

the other way

at the point where you should begin

your repeat. Just to illustrate, let's pretend that he wants you to repeat only the last four measures of the tune; then he would use the repeat signs in this way:

You would then repeat only the four measures between the dots. 145 You must also have noticed that measures 7 and 8 have this sign over them IT I and that they are followed

by two more measures marked thus: \T.

^m

This instructs the reader that he is to play or sing the measures marked rj 1

the first time through, but that in making the repeat, he is to substitute for them the measures marked

Measures 7 and 8 are called the first ending, and the other

REPETITIONS

115

two measures the second ending. Their use saves the copying of six measures in this case, and of whole pages in some compositions. 146 Sometimes, especially in long pieces, the composer will indicate a repeat by writing D.C., which is an abbreviation for the Italian words da capo, meaning "from the head" or "from the top." If he wants you to go back to some special point, but not all the way to the beginning, he may mark

that special point with a sign, either -0- or % , and write

D.S. which is an abbreviation for the Italian words dal segno, meaning "from the sign." 147 If the phrase al fine ("to the end") is added (D.C. al fine, or D.S. al fine), it means that you are to go back to the beginning or to the sign, as the case may be, but repeat only until you reach the word Fine ("end") written in the music. Here are two examples each of which includes an ordinary repeat sign as well as a D.C. or D.S.:

THE MARINE'S HYMN'

M*atur*

FINE

^C/UJjJU-iJ^^

mr

D.C. aX FINE 7 I

^Sometimes you may hear this tune in a slightly different version, with the following tones in measures 5 and 6:

$

S x

x 4

m

"OLD FOLKS AT HOME"

L

$ t j sm\i

m

%

j J JjJJUr Jl ri J j-j

T3"

FINE

| r' FT Ju- Jl ^ ^

148 Notice that in 'The Marine's Hymn" the repeat instructions occur after only part of the measure has gone by (i.e., there are only three beats, instead of the four which we expect in \ meter, in the last printed measure where the D.C. appears). A Da Capo, a Dal Segno, or an ordinary repeat sign, need not come at the end of a measure; it may be used anywhere within the measure. This is especially frequent in pieces which begin with an upbeat, as "The Marine's Hymn" does.

149 When the composer wants one whole measure to be repeated, he saves himself the trouble of writing it a second time by using this sign between the bar lines of the second measure:

For example, the first four measures of "Jingle Bells" could be written this way:

jm jijikiJT ^

REPETITIONS

117

If a composer, for any reason, wants to repeat a measure several times, he may use as many of these signs as he finds necessary:

^1 J- ]JJJ3 | y. | k | z

moans

j 8 PjJWi jjJTOujJJPl

150 When single notes must be repeated, as they often must, especially in instrumental music, there are still other shorthand devices. A beam, over or under a single note, is understood to divide the note into the shorter values indicated by the beam: for instance, a half-note with an eighth-note beam through its stem, means "a half-note's worth of eighth-notes" :

m

I rrrrJ-uH

A whole-note with a double beam under or over it means "a whole-note's worth of sixteenth-notes" (sixteenths because of the double beam) :

Here are a number of additional examples:

P

^

mmmm»

SUPPLEMENTARY SYMBOLS AND DEVICES

I

i

P^

m

m

m

WMH I

m

MHH-

P

151 The word tremolo (abbreviated trem.) written over one of these beamed notes means that the note is to be repeated as fast as possible, without sticking literally to the number of subdivisions indicated by the beams. Thus,

^ trem. trem.

» f " flr § f

does not mean that the half-note is to be divided into exact thirty-second-notes or sixty-fourth-notes, but that the player is to repeat Bs as fast as he possibly can.

REPETITIONS

119

152 Often it is desired to repeat, not a single tone, but a pair of alternating tones, like this:

This can be abbreviated by writing both of the notes involved as half-notes (in this case) but adding the double beam for sixteenth-notes to connect their stems:

Ppi

$

m>om

I

It is as though we said, "A half-note's worth of alternating As and Cs in sixteenths." Notice the difference between this abbreviation and the one for repeated notes without alternation :

It is the beam connecting the two half-notes which calls for alternation instead of simple repetition. This symbol cannot be confused with a pair of ordinary sixteenth-notes because of the hollow white heads of the half-notes; ordinary sixteenth-notes would have solid black heads, of course:

SUPPLEMENTARY SYMBOLS AND DEVICES

ORNAMENTS

153 The symbol tr indicates a trill, which is a rapid alternation of the given note with the note just above it. For example, if you see the tr over the note B, you play a rapid alternation of Bs and Cs:

^

^

m »q n « qpp rox ima7»

Notice that we have said "approximately," for the trill does not require any specific number of alternations, or any specific speed of alternation. In general, one alternates the two notes involved as rapidly as possible, until the written value of the given note is used up. You will notice that this is very much like the principle of the tremolo. Thus, in the instance cited here, one would not have exactly eight thirty-second-notes, but rather "a quarter-note's worth of Bs and Cs, alternating as fast as possible." The effect is to embellish or decorate the B.

It is also permissible to begin with the embellishing note (the upper one). That is,

tr

$

^

£

wa y toimti i m i ■ > pla y ed . ^

¥

beginning the trill on the C instead of the B. Many performers use this second interpretation of the trill in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century music; the first type, with the given note at the beginning, is more common in nineteenth- and twentieth-century music. 154 The trill is only one of a great many so-called ornaments used in music. They are very seldom encountered in the music of our time, but they were extremely common in the

ORNAMENTS

121

music of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The study of the old ornamentation is a forbiddingly complex one. Not only the scholars of today, but even the authorities of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, disagree constantly on the way in which some of the symbols are to be read and interpreted. Therefore, it is impossible to make general and simple rules, and unless one has really studied the whole literature of these centuries and knows the context in which each example occurs, it is fruitless to become involved in the perpetual arguments about them.

At the risk of oversimplifying the problem, we will nevertheless give here one rule of thumb which covers the most common kind of ornament, the grace-note, since the student is likely to encounter it even in relatively simple music. The grace-note, printed usually as a miniature eighth-note, with a little crossbar through the stem and hook, £ is used for notes so short that it is not necessary to bother with computing their exact length. The grace-note is not counted at all in adding up the beats in a measure, and its time usually is stolen from one of the more important notes on either side of it (most often from the preceding one, but sometimes from the following one). For example,

$

PS

Z2I

it pl« y »d-

•^proxi m ately ,

There is another kind of grace-note, which is printed without the little crossbar through the stem, as a miniature sixteenth-note, eighth-note, or even quarter-note. It is found in old music:

Written

■ h Uj- lej-

The first way is more common; the second is more correct.

SUPPLEMENTARY SYMBOLS AND DEVICES

This grace-note without the crossbar seems generally to have been played as though it were a real note of the value indicated by its stem and hooks (its value being taken out of the following note, to which it was tied) :

««*•* y* Cfr_f f f f r

If it were printed

m

^

it would be played:

P

If you ask why such an illogical custom was adopted, and why these passages were not written in the first place as they were meant to sound, the answer is that they arose at a time when strict rules of musical composition limited the tones which properly could appear on a strong beat, and any others had to be shown or explained in their relationship to these permitted ones.

SYMBOLS FOR DYNAMICS

155 Acquaintance with a few more abbreviations and symbols, related neither to rhythm nor pitch, but to dynamic level (how loud or soft the sounds are to be), is necessary for reading music.

These symbols are usually printed just below the music staff.

156 The Italian word forte, meaning loud or strong, is abbreviated to the letter^. Piano, meaning soft, is abbreviated tojp.

From these two, a whole series of gradations is evolved. Fortissimo ("very loud") is abbreviated jQf . Pianissimo ("very soft") is PP . Between f and p, there are mezzo forte (medium loud, a little softer than forte), abbreviated mf, and mezzo piano (medium soft, a little louder than piano), abbreviated mp. Occasionally it is useful to represent a degree of loudness even greater than £f ; in such cases, jSy is used. Similarly for something even softer than PP, we write PPP .

157 The symbol fp (forte-piano) indicates that the tone so marked is to be begun forte but immediately dropped to piano. Sforzato and sforzando (abbreviated sf , sfz , or

f» , meaning "forced" or "forcing"), are slightly different — tones so marked are to be suddenly forced or accented, but there is no indication that they are to be dropped to piano immediately afterward.

158 If the music is to grow gradually louder, instead of suddenly, the word crescendo ("growing") appears. It is abbreviated cresc. Diminuendo and decrescendo, abbreviated dim. and decresc, respectively, show that the music is to grow gradually softer. Sometimes crescendo is indicated, without any words, by the symbol

and decrescendo or diminuendo by the symbol

159 For more of these terms, consult Appendix Two (See p. 155).

If a composer wants you to give a special accent or emphasis to a note, beyond that which it would normally receive,

he can put the accent mark over that note. It looks like this:

For example:

$m

Some musicians write the accent mark vertically, instead of horizontally, like this:

$

SYMBOLS FOR ARTICULATION, STYLE, ETC.

160 Dots over or under notes indicate that they are to be played in a short, crisp fashion, each note separated from the surrounding notes. This is called staccato, from the Italian word meaning "separated." In effect, this really means that they are played a little shorter than they are written:

wm

at a fast or moderate tempo is aproximately the same as

|ip 7 rrP

161 If pointed wedges are used instead of dots, they are taken to indicate an even more crisply separated execution, that is, more staccato:

^*r r r

is played approximately

In addition, the wedge often adds a sort of hammered, almost accented quality to a note.

162 The opposite of staccato, that is, the smooth connection of notes, is indicated by the slur:

Notes so marked are to be played or sung as smoothly as possible, without any interruption between them. This style is called legato, from the Italian word meaning "bound together." Notice that this is really the same symbol that is used for the tie. (See p. 15). It is called a tie when it connects notes of the same pitch so that they become one longer note, whereas it is called a slur when it connects notes of different pitch so that they are played or sung smoothly and without individual articulation. Really the tie is just a special case of the slur — the case where two notes are connected so smoothly that they become one note. It is even possible to have a tie under a slur, when a note which has been lengthened by the use of a tie is to be connected smoothly to a different note:

=2^

%

Here the lower of the two curved lines is a tie which is required to make one continuous D by joining the half-note D in the first measure with the quarter-note D in the second measure; the upper curved line is a slur which connects the resultant D smoothly with the B. 163 This is a good time to note that ties and slurs affect the rule about accidentals differently. You will remember that, in general, a flat or sharp is assumed to hold for all of the measure in which it appears (See p. 88 ff.). Since a tie makes

SUPPLEMENTARY SYMBOLS AND DEVICES

one long note of two shorter ones, an accidental before the tied note will hold for the entire length of the tie, even when it carries over into a second measure:

P

Here the flat applies not only for the second beat of measure 1, but also over the bar for the first beat of measure 2, since these two beats have been united into one by the tie. If there were no tie, it would be assumed that the flat lasted only to the end of the measure, and that the first beat of measure 2 was natural:

P

h

m:

i

In such cases, some musicians write in an extra natural (although theoretically it is superfluous) just to make sure that the reader understands their meaning:

j i r 'r r"r

Often they will put the extra accidental in parentheses, as has been done here, to show that it is not really necessary but is supplied to avoid doubt in the reader's mind. 164 When such a sharped or flatted note is tied over into the next measure, therefore, the accidental holds till the end of the tie, but not for the rest of the second measure. For instance, if another E were to occur in the second measure after the tie, it would be read as E-natural:

•^ (b) dp

SYMBOLS FOR ARTICULATION, STYLE, ETC.

127

since the force of the flat would have expired with the end of the tie. Even a slur over the whole phrase would make no difference, since a slur shows only a smooth style of performance and does not affect the length or pitch of the notes under it.

(i» op

165 Dashes over notes indicate a slight lengthening. Some performers actually make such tones a trifle longer than written, but most interpret the dash or "long mark" to indicate the holding of the separate notes to the full extent of their value, with as little break as possible between notes. This is slightly different from the legato slur, which actually binds notes together into a single smooth phrase. The dashes leave the notes separate, but with as little "air space" as possible between them.

mm

pp

166 Occasionally you will see dots under a slur, an apparent contradiction. The intention of this notation is to combine the conspicuous qualities of both dots and slurs — that is, to give the over-all effect of notes that belong together in a phrase, yet to separate them slightly from each other. It is a sort of compromise between the two.

1 in" i

is played approximately like

SUPPLEMENTARY SYMBOLS AND DEVICES

The breaks between notes are very slight, the player becomes aware that a continuous phrase is desired, and even his awareness helps to communicate this effect to the listener. 167 In vocal music, when words are printed with a melody, the notation sometimes is so arranged as to make the separate syllables of the words apparent at a glance. This is done by using separate hooks for eighths and sixteenths (or any other notes with hooks), instead of beams, whenever they are to be sung with separate text syllables; beams are saved for the cases where several eighths or sixteenths are sung to one syllable. An example will make this clear. Suppose the words "Never to return" are set to music as follows:

it p p f

Ne - ver to

2

zz

re - turn

Since each syllable gets a separate tone, separate hooks are used, and the reader knows immediately how the notes fit the syllables. This phrase would not be written with a beam in vocal music, although in instrumental music the beam would be considered easier to read, since there would be no question of reading syllables of words:

(The same phrase as written for instrumental music, but not for vocal music.) 168 If a single syllable gets two or more eighth- or sixteenth-notes (or any other kind of note that has a hook), a beam is used to show that they are all sung to one syllable. For instance, if the last syllable in the example above were sung to four eighth-notes instead of one half-note,

SYMBOLS FOR ARTICULATION, STYLE, ETC.

129

4^ F P r 1

ne - ver to re - turn

a beam would be used for the last four eighths to show that all of them are sung over a single syllable, "-turn." 169 Strictly speaking, a slur is needed to show that the last four eighths above are sung smoothly to one syllable, but since the beam is assumed to suggest as much, the slur is often omitted in such cases. Occasionally, however, the student will see such a passage printed with both beam and slur:

f

^

^

Ne- ver to re - turn

170 The slur is more necessary when the notes sung to one syllable are of longer value than eighths, because such notes cannot be grouped under a beam. If "-turn" were sung to two quarter-notes, a slur would be advisable to indicate the smooth joining of the two notes during the singing of the one syllable:

B

ne

ver to

re

turn

171 Note that a hyphen, or a string of hyphens, is used between syllables of a word, but that a continuous line is used at the end of a word, or for a word of one syllable, when it is desired to suggest the flow of music during that word.

172 Here is "Jingle Bells" written as instrumental music (as we did it before, on p. 113), and then as vocal music with words. Observe carefully the differences in the use of beams.

SUPPLEMENTARY SYMBOLS AND DEVICES

Instrumental:

r^r

^^

m

^tg

Vocal with words:

^

£

X

Jin- gle bells, Jin- gle bells, Jin- gle all the

r r p

p

^2

; l;

way. Oh what fun it is to ride in a

^

S

t=

one horse o - pen sleigh.

' CT IT _c

one horse o pen sleigh.

PART FIVE

Tonality

173 With the information you now have, plus that contained in the Appendices, you should be able to read any simple melody. However, there is an important concept behind most of the melodies you will encounter, the understanding of which will make your reading of music more intelligent and more meaningful — the concept of tonality.

174 In almost any melody, one tone can be found which seems more important, more final, than any of the others used in making the melody. Instead of trying to explain this in words, let's illustrate by inventing a laboratory melody with which to experiment. Here is a simple one of four measures, using the tones C-D-E-F-G-A in various combinations:

ModeratO Ta Ta Ta Ta Ta Ta Ta _ Ta Ta Ta Ta Ta Ta Tq _ CDEF EDA OFEF EDC

m

m

First you must try it at the piano, singing along on the syllable Ta as we have done in the past. Since there are no flats and sharps, we know that the whole melody can be played on the white keys. The first note is Middle C, after which the melody moves up through D, E, and F on the white keys (measure 1). In measure 2, we move back through E and D, and then jump up to A. (Consult your keyboard chart, if you have to.) This is the first phrase, two measures long. In the last two measures, the melody moves down through G, F, and E, returns for one note to F, then continues down again until it reaches the Middle C on which

TONALITY

it began. The rhythm should be simple for you, mostly even quarter notes, with a half-note to end each phrase. Try the tune over as many times as necessary, until you are perfectly sure of it, since it is going to serve as our guinea pig in this experiment. It would be a good idea to memorize it if you can:

Ta Ta Ta To C D I F

Ta Ta Ta IDA

Ta Ta Ta Ta

a f i f

Ta Ta Ta IDC

175 Now, if you substitute various other tones for the last C, you will find that none of them sounds as satisfactorily final as the C. For instance, try an F as the last note instead of C:

m

i

w

s * i j

I think you will agree that the melody sounds somehow "incomplete" with the F.

176 Try another tone, B for example:

I'jjj

i

This sounds even less finished than the F, or at any rate, not so final as the original C. (At this point, you may want to play it again in its original form, just to remind yourself how the C did sound.)

177 TryD:

Pi

zz

t

Better than the B, perhaps, but certainly not so good as the C. 178 Try E and G:

ft* J J J J I J J ' J 1^ J J JIJ J J

t

|*ij J JU j J U J J J I J M

These may seem a little more stable than some of the others, but a comparison with the C will convince you that it remains the most naturally conclusive tone of all.

179 If you experiment with some of the black keys, you will find that they sound even more remote. You might try Ft, D$, or any others you wish:

P

m

#

m

w

180 In other words, for this particular melody, the C seems to be the most satisfactory final note, the note toward which the others insist on gravitating, as though some strong force were pulling them there. The other notes have varying degrees of restf ulness or activity, with respect to the C, and if we wished we could arrange them in a sort of table of relative activity.

181 This is true of most melodies - that some single tone usually tends to assert itself as the principal one. This central

tone is known as the tonic (or sometimes, the key center), and a piece of music in which the other tones are related to such a key center is said to be tonal. The whole concept of this relationship to a central tone is called tonality.

182 When, as in our experimental melody above, the final pull is toward C, the piece is said to be "in the key of C." Each melody has its own tonic or key center. If the tonic is G, the melody is "in the key of G"; if the tonic is E-flat, the melody is "in the key of E-flat," and so on. A melody need not end on its tonic, although it usually does; when it is clear from the nature of the melody which is the tonic, the composer sometimes takes the liberty of ending on one of the closely related tones other than the tonic.

183 The key of E-flat consists of a certain group of notes, all related in varying degrees to their tonic, E-flat; the key of G has another group, all related to G; the key of Ft has another group, all related to Ftf. These groups are called scales. When we state the key of a piece of music, we are giving a sort of alphabet or vocabulary of the tones available for use in that piece. They may be arranged in all sorts of different combinations. Tones outside the key occasionally may be introduced in passing, but will never assume the importance of those directly related to the tonic.

184 When we know the name of the tonic, therefore, we know pretty well, after a little experience, which tones to expect in its company. The key of C, for example, will have all "white" notes (naturals), no sharps or flats. The key of E-flat will have several flats and the rest natural. The key of A will have several sharps and the rest natural. In other words, for each key there will be a characteristic key signature.

185 To explain how this works is a bit more complicated. Since it is not absolutely necessary at this stage of the game (after

all, you have already been reading melodies provided with key signatures, without knowing how they were related to their keys), the explanation is given in the following Appendix where the ambitious student can find it if he wishes to penetrate further. However, it would be more advisable at this point to find a good instructor for the more advanced study, or at least to consult a good textbook. Paul Hinde-mith's Elementary Training for Musicians (Associated Music Publishers, N. Y.) is highly recommended for the serious student, as well as the early pages of William Mitchell's Elementary Harmony (Norton, N. Y.).

APPENDIX ONE

Scales and Key Signatures

186 We know that there are only twelve different tones from which all our melodies are made: the white notes on the piano keyboard account for seven of them - A B C D E F G, the black notes for the other five - F' Gl Al C' Dr. (Of course the five black notes can also be called by their flat names — Gb Ab B?> Dd Eb - but they are the same five keys on the piano.)

187 Some melodies use all twelve of these tones in various patterns and combinations, but most melodies use only seven or eight of them. In fact, you can construct perfectly good melodies with fewer elements than that; for instance, you might try using only the five black keys and making up melodies for yourself at the piano keyboard. If you take them in different rhythms, and rearrange the order of the five notes in all possible ways, moving sometimes smoothly from one to the next and jumping around at other times, you will find that there are countless pleasant melodies to be made from these five tones alone. The only limit is the inventiveness of the composer!

"Auld Lang Syne" is a familiar tune which can be played on the black keys alone:

m

fJ ii j.jjbJuji^i'r

PS

l^f^^JliJ-bi'J^lJ^jJjli

SCALES AND KEY SIGNATURES

flfr Vfrj i ai-jJ'E PEfy

te=rf

1CL.

e^

prbj|M-bj'ip*^Mb jjj

w

Others are "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot," "Nobody Knows the Trouble I've Seen," and "Short'nin' Bread," to mention just a few.

SCALES

188 If you want to find the group of notes, or scale (see p. 134), from which any melody is built, you have only to a) list all the tones used in the melody, b) eliminate any duplications, and c) arrange in alphabetical order what remains, beginning with the tonic.

189 For instance, the "Doxology," which we used in Chapter III (p. 102), has the following notes:

¥

¥5fel

%

*

Bb Bb A G F Bb C D D D D C Bn Eb D C B b

^

C D C Bb G A Bb F D Bb C Eb D C Bb

If we eliminate the repetitions of notes which are used more than once, we have: Bb A G F C D Eb. And if we arrange them in alphabetical order, beginning with the tonic (which is Bb, as you can test by trying to end with some other tone), we have: Bb C D Eb F G A. This is the scale on which the "Doxology" is based. In other words, it is the inventory of the raw material from which the melody is made.

THE MAJOR SCALE

190 Theoretically the number of sucn scales from which melodies can be made is very great, but during the past few hundred years, European and American composers have tended to use only two or three of these scales for most of their music. The most common one is called the major scale, and the simplest example of it can be obtained by taking the white keys on the piano, from one C to the C an octave higher: C D E F G A B C. Such a scale has seven different tones, plus the repetition of the tonic at the end, one octave higher — or eight tones in all. The tones which make up a scale are called its steps or degrees.

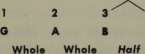

191 Now you will remember that the white keys, although they seem on the surface to be equal, really have differing distances or "intervals" between them. The distances in pitch from B to C, and from E to F, are half-steps, whereas the distances between the other notes are whole-steps.* Therefore, the scale from C to C has the following succession of whole-steps and half-steps:

%

■ ' o =°:

3ZT

^ O ^

CDE F GABC

Whole Whole Half Whole Whole Whole Half

192 This is what characterizes a major scale: that its eight tones, when arranged in alphabetical order, beginning with the tonic, will always have a half-step between the 3rd and 4th tones, a half-step between the 7th and 8th tones, and whole-steps everywhere else:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Whole Whole Half Whole Whole Whole Half

It is the small interval between the 7th and 8th tones which *See page 78.

is perhaps the most distinctive feature of the major scale, for the 7th tone, as a result of it, gives the impression of always being drawn strongly toward the near-by eighth tone, which is the tonic. The tonic in the major scale is definitely the center of attraction.

CONSTRUCTING MAJOR SCALES

193 In the scale of white notes from C to C, the half-steps fall in the right places to produce a major scale. But this is not quite so if you- begin the white-note series on G:

4 5 6 ^^ 7 8

C D E F O

Half Whole Whole Half Whole

Here the first half-step occurs between the 3rd and 4th tones, it is true, but the other half-step falls between the 6th and 7th, instead of between the 7th and 8th. Indeed, since there is a whole step between the 7th and 8th in this scale, the major scale's characteristic drive of the 7th step toward the 8th (tonic) will be absent.

194 If it is desired to construct a major scale beginning on G, however, this can be done by analogy with the one on C. It will be necessary to do a little "plastic surgery" on the upper part of the scale to imitate the basic pattern which requires a half-step between 7 and 8 (and a whole-step between 6 and 7). This can be achieved easily by using Fff instead of F.

^X \k*C **

%

£

^ '. f% a

TJ

_m

12 3 4 5 6 7 8

OABC D EF&G

Whole Whole Half Whole Whole Whole Half

By raising the F a half-step to make it FS, we bring it closer to G, so that the F3 now has the same relationship to its tonic, G, that the B in the model scale had to its tonic, C.

CONSTRUCTING MAJOR SCALES

141

Moreover, Dy raising the F to Ft, we have killed another bird with the same stone — we have enlarged the space between E and F (6 and 7) from a half-step to the desired whole-step. In other words, with the use of Ft instead of F, we can make a major scale beginning on G which has the same plan as the major scale beginning on C. Compare :

1 2 3

O A B

Whole Whole Half

4 5 6 7 /\ 8

C D I Ft O

Whole Whole Whole Half

195 Throughout any melody using this scale on G, the tendency will be to have all the Fs sharp, and none of them natural, and it will save much writing in of the sharp, if we put it in the key signature at the beginning, once and for all. "America," the first part of which we studied on p. 95, can serve as an example of a piece written "in the key of G major." Here is the entire melody:

<Tii J J J u. J) J i r r r i f ^

GOAF* OABBCB AO

tm

^^

AGFSG DDDD CBCCC

i r p J| r cr^'r fHOt ^^

C BABCBAGB CDECB AG

If you eliminate the doubles, and write the different notes employed in alphabetical order, beginning on the tonic G, you will have the following array: GABCDEFf (G).

196 Actually the high G does not appear in this melody; it is the low F# which is drawn toward the lew G, but the principle is the same, since the 8th tone of a major scale is always a duplication of the name of the first, as you will remember, and is introduced, in the scale, just for the sake of making clearer the gravitational pull of 7 toward the tonic (see page 139). The higher octave sometimes may not be included in the actual melody or, on the other hand, additional octaves, still higher, may be included without affecting the fundamental nature of the relationship: a tonic is a tonic, and it will act as a tonal magnet, drawing the 7th degree of the scale toward it, whether they are in the middle of the keyboard, way up at the high end, or down at the low end, whether they are sung by a voice, or played on an instrument.

197 A major scale can be constructed, beginning on any of the twelve tones, white or black, just as we constructed one on G, simply by adjusting the distances between the tones so that half-steps fall between 3 and 4 and between 7 and 8, and all the other distances are whole-steps.

198 It will be instructive to try a few. For instance, let us solve the problem of constructing a major scale on D. Beginning on D, take in alphabetical order the letter-names of the white notes until you have come around to D again:

^

$

o n . n

i l O EgE

1 2 /^ 3 4 5 6^^ 7 8

DEFQABCD Half Half

Both half-steps come in the wrong places. We must go

through the series of white notes, step by step, introducing accidentals where necessary to make the pattern fit the model of the C-major scale, with whole-steps everywhere, except between 3 and 4 and between 7 and 8. The first interval, from D to E, is all right, since it is a whole-step as it should be, but the second one must be enlarged by pushing the F up to Ft. By raising the F to Ft, we not only create a whole-step between 2 and 3, but we also simultaneously correct the distance between 3 and 4, for the Ft now makes the desired half-step with G:

The intervals between 4 and 5, and between 5 and 6 are whole-steps as they should be, so our next problem is to widen the space between 6 and 7. This we can do in the same way by raising the C to Ctt, and here again our next problem will be solved by the same stroke, for the Ct will now make the desired half-step with the final D:

$

w

m

XI

T3 *

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

D EF# GABC8D

Whole Whole Half Whole Whole Whole Half

The key of D, therefore, will have two sharps in its key signature, Ft and Ct:

i

&

jggl " ° g

~rr

199 B major will be just a little more complicated, but the same

SCALES AND KEY SIGNATURES

method will work. Beginning on B, take in alphabetical order the letter-names of the white notes:

#

jO_

3m

12 3 4

B C D E

Half Whole Whole Half

5 6 7 8

F G A B

Whole Whole Whole

Both half-steps are in the wrong places. Between 1 and 2 we need a whole-step, so we must raise the C to C#:

¥

xr

1 2 3

I C* 0

Whole Half

But this creates a half-step (C# to D) between 2 and 3, where it is not wanted. So we now must raise the D half a step to Dtf:

*) 1 2

33:

12 3 4

B C» D* E

Whole Whole Half

This not only gives us the desired whole-step between 2 and 3, but at the same time puts the necessary half-step between 3 and 4, by making it Dtf to E, instead of D to E.

Between 4 and 5 we need another whole-step, so we must raise the F to Ft :

$

3eE

2~

5

3

d:

331

*

CONSTRUCTING MAJOR SCALES 145

But this creates a half-step between 5 and 6 where it is not desired, so we must raise the G in turn to G#:

I

-«-

^^

X3I

*«*=£

£*_

1 2 3

B CS D2

Whole Whole Half

4 5 6 7

E F; G: A

WhoU Whole Half

And since this, once more, creates an unwanted half-step between 6 and 7, we must raise the A to A$:

$

#o #" f t'

do:

-«-

VT

12 3 4 5 6 7 B~~

B C~ D~ E Ft Of AS ■

WhoU Whole Ho// Whole Whole Whole Ho/f

This not only makes a whole-step between 6 and 7, but produces the final half-step between 7 and 8. The key of B major, then, has a key signature of five sharps, C$ DS F$ Gt and Alt:

i

y*

<^ ^L

;;^

200 As an example of a scale which begins on a black key, do F- major. Beginning on F2, you must take in alphabetical order the letter-names of the white notes. (The Fs itself is a black note, of course, but the whole point of the problem is that it is given as such.)

^X —

i

z^;

m

z s

m:

^

2 FJ O

Half

4 5

B C

Half

SCALES AND KEY SIGNATURES

Both half-steps are in the wrong places. Between 1 and 2 we need a whole-step, so we must raise the G to Gtf. But this will make a half-step between 2 and 3, so we now must raise the A to At:

$ it" ft° i

h

^^

2

3 AS

In this way we create, at the same time, the desired half-step between 3 and 4. If you continue by the same method, you will have to raise the C to Ctf, the D to D#, and the E to Ft (since E to Ft, wider than E to F, is a whole-step, and therefore will not do between 7 and 8).

$

y\

ft" flo #

n=fc

tin fto tV'

2 3

H Gt *&

Whole Whole Half

4 5 6 7, 8

B C$ D* E* F*

Whole Whole Whole Half

The key of Ft major has six sharps in its key signature, Ft

Gt Afl C# D# and E#:

it§

*

331

m

201 Before going any further, you should work out for yourself the major scales beginning on A, E, and Ctf. You will find that A major has a key signature of three sharps, E major of four sharps, and Ct major of seven sharps (every note is sharped in Cff major!).

202 The major scale on F adds a slight variant of the process

which is useful in other scales, too. Beginning in the usual way, take the white notes from F to F:

^X

i

o " =

31

12 3 4 5 6 7 8

FGABCDEF Half Half

Although the last half-step is in the correct place, the first one is not. Let's take the intervals one at a time. Between 1 and 2, and between 2 and 3, the desired whole-steps already exist, so nothing need be done there, but between 3 and 4 the space is too wide, not too small as in all our previous cases. We cannot correct it by raising the A to A#, because that would spoil the correct interval between 2 and 3, so we must loiver the 4th degree, B, to Bb:

$

ZEE

^

12 3 4

F O A Bb

Whole Whole Half

This will automatically correct the interval between 4 and 5 at the same time, since the unwanted half-step from B to C will be enlarged to B-flat to C, and the entire scale will now fit the pattern perfectly:

.Z\

$

ZEE

^

331

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

F O A Bb C D E F

Half Half

The key of F major has one flat, Bb, in its key signature:

j" - ■■ ■ " °

203 Try one which begins on a flatted note, Db for instance. The series of letter-names of white notes between Db and Db will be:

$

i i o *S

1 2 1 4 5 6 7 8

Db I F • A ■ , C Db

lVi Half Half Half

Notice that the first interval, between 1 and 2, is neither a whole-step nor a half-step but a step-and-a-half! (D to E would be a whole step, but this interval is widened even further by lowering its bottom member to Db; therefore it is even half a step wider than a whole-step; i.e., a step-and-a-half.) To correct it, we must lower the E to Eb, thereby producing the usual whole-step for the interval between 1 and 2, and at the same time automatically correcting the next interval by changing the half-step from E to F into a whole-step, E-flat to F:

$

[;u b <

1 2 3

Db lb F

WhoU WhoU

But the space between 3 and 4 is still too great, so we must reduce it to the required half-step by flatting the G:

$

bo » t>Q EEEEE

12 9 4 5

Db lb F Ob A

WH«W Wh*fo Half lVi

But by doing this we have enlarged the space between 4 and 5, which was a whole-step to begin with (G to A), so that it is now V/ 2 steps (Gb to A); therefore, we must proceed

as we did for the very first interval, by lowering the A to Ab:

$

*Y

bo .. bo E*E

2 3 4 5 6

Dp lb F Ob Ab B

WhoU Whole Half Whole IVi

This, of course, does the same thing to the next interval, which in turn must be reduced by lowering the B to Bb. But once this is done, the whole problem is finally solved, for the half-step between 6 and 7 becomes the correct whole-step (Bb to C) and the final half-step between 7 and 8 remains:

$

bo " ^

zsx

^Y 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Db lb F Ob Ab Bb C Db

WheU WheU Half WhoU WheU WheU Half

The key of Db major has five flats, Db Eb Gb Ab and Bb, in its key signature:

$

^

ffi

xa:

TJ ** "

204 At this point, you must work out for yourself the major scales beginning on Bb, Eb, Ab, Gb, and Cb. You will find that their key signatures have respectively, two flats, three flats, four flats, six flats, and seven flats. (Every note is flatted in Cb major.)

205 Observe that, since Cs and Db are really the same note on the piano keyboard, the scales of Ct and Db will sound alike when played on the piano. The same is true for Ft and Gb, and for Cb and B.

206 You may already have noticed that, in writing key sig-

SCALES AND KEY SIGNATURES

natures at the beginning of a piece, it is the custom not to place the sharps or flats on the staff in a haphazard manner, but to write them always in the same order. This is just a convention, but it is a useful one because the look of each signature quickly becomes familiar and the reader knows at a glance which key is intended without identifying the various accidentals or even counting them. Therefore, if you plan to continue with your music reading, it will be worth your while to memorize the following tables of key signatures. Write them several times each day, until each pattern is second nature to you:

KEY SIGNATURES, MAJOR SCALES

Treble Clef

Bass Clef

I

C major

m

*

h

D

H

m

a

m

m

m

¥tt f t\ h h%tt

m

m

Ft

#*$*,&

m

a

^^

rp

Treble Clef

Bass Clef

$

m

^

Bp

P

m

Et>

&

Ab

»

Dp

m*

fc*

m?

Ob

^

F

m

s

Cb

^^

m

&¥

THE MINOR SCALE

207 All of this discussion has been concerned with the major scale, which was described as the scale most frequently used by European and American composers during the past few hundred years. Another important scale during this period has been the minor scale, which has its own characteristic

arrangement of half- and whole-steps. Just as the series of white notes beginning on C serves as the model for the major scale, so the series of ivhite notes beginning on A serves as model for the minor scale:

$

ii o —Q-

n Q E E

12 3 4 5 6 7 8

ABCDEFOA

Whole Half Whole Whole Half Whole Whole

In minor scales, the half-steps occur between 2 and 3, and between 5 and 6. You can construct a minor scale on any note by observing this pattern.

208 In other words, the major scale on C uses the natural half-steps, B to C and E to F, with no accidentals, and the minor scale on A uses the same natural half-steps, with no accidentals, although these half-steps fall between different degrees of the scale in minor than in major. This means that C major and A minor* have the same key signature — no flats or sharps.

209 Similarly, for every major scale, there is a minor scale that uses the same key signature, and that minor scale will be the one beginning on the 6th degree of the major scale, just as A is the 6th degree in the scale of C. So, if you want to know which minor scale has the same key signature as F major (one flat), you have only to take the 6th degree of the F major scale, which is D, and the answer is D minor. If you want to know which minor scale has the same key

♦Some books use capital letters to indicate names of major scales and small letters to indicate minor scales. This permits them to tell the reader with a single letter, as a sort of shorthand, not only the name of the scale but also whether it is major or minor. For example, A would mean A major and a would mean A minor.

SCALES AND KEY SIGNATURES

signature as F# major (six sharps), take the 6th degree of Ft major, which is D#, and the answer is Dtf minor. For G major, the 6th degree is E, so the same key signature (one sharp) will be shared by E minor.

210 Now, in actual practice, the pattern of the minor scale is less rigidly maintained than is that of the major. This is because the whole-step between 7 and 8 in minor makes the pull toward the tonic weaker than in major, where the distance to the tonic is only a half-step; consequently the 7th degree in minor is often (but not always) raised in imitation of the major, and the 6th degree is sometimes (but not always) raised along with it in order to smooth over the motion from 6 to the raised 7. Even when this is done, the same key signature is kept for the minor scale, the extra accidentals required for the raising of the 6th or 7th degrees being written on the staff each time they are desired. For example, the following melody is in A minor, with no flats or sharps in the key signature, although there is a Gt, representing a raised 7th degree, in measure 3:

Ophelia's Song in "Hamlet"

friNr i rAJ

m

2

A minor

¥

ass

e

m

211 The form of the minor scale outlined on page 151 is known as the natural minor scale. When its 7th degree is raised to make a half-step between 7 and 8, the resulting scale is called the harmonic minor scale:

ZX ,/ / ' N Vi tfo ^-

$

XX

XX

ABCDEFGftA

Whole Half Whole Whole Half l'/i Half

When, in addition to the raising of the 7th degree, the 6th degree is raised along with it, the new scale is called the melodic minor scale, and the two raised tones are used only when the melody ascends; in descending passages in melodic minor, the 6th and 7th degrees are restored to the original condition in which they occurred in the natural minor scale, since the 7th step (and the 6th with it) is no longer heading upward toward the tonic but downward away from it:

^X = _ He* Ito

$

. t° *

12 3 4 5 6 7 8

ABC D E Ft Gt A

Whole Half Whole Whole Whole Whole Half

$

*~-±

ICE

ICE

H

8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A O: P = E DC B A

Whole Whole Half Whole Whole Half Whole

Notice that in all three cases the 3rd degree of the minor scale is only half a step from the 2nd, instead of a whole-step as in major; this is the most characteristic feature of minor scales.

212 Since you now must realize that each key signature has two possible meanings (a major scale, and the minor scale beginning on its 6th degree), you may wonder how one can judge from the key signature what the key may be. The truth of the matter is that the key signature alone is not infallible as a guide, but taken together with certain other indications, it will usually give the necessary information. For example, in "Ophelia's song" (page 152) we have a key signature of no sharps or flats, indicating either C major or A minor; but the two most prominent points in the piece, the beginning and the end, are on the note A, so we have

SCALES AND KEY SIGNATURES

strong reason to believe that A is the tonic, rather than C. Moreover, the Gt in measure 3 would have no place in C major, but is frequently found in A minor as a raised 7th degree. 213 We now should revise our table of key signatures so that the two meanings of each signature are indicated:

KEY SIGNATURES, MAJOR AND MINOR SCALES

Treble Clef

Bass

Clef

$

C major A minor

m

G major E minor

*

I

D major B minor

*

1

a

i

m

A major F$ minor

s

E major Cg minor

Hi

Treble Clef

Bass

Clef

pi

i

B major G$ minor

^^f

Hsl

F$ major D$ minor

^e

Bi

C$ major A$ minor

m%

F major D minor

Bj major G minor

Treble Clef

Bass Clef

$

m

Eb major

C minor

s

BE

»

Ab major F minor

s

fefe

Dn major Bb minor

m

u*

te

m

Gb major Eb minor

HP

m

Cb major Ab minor

sip

APPENDIX TWO

Vocabulary of Some Important Foreign Terms Used in Music

These terms are presented here in groups, according to subject matter.

In general, the Italian terms are the most widely used. Their German and French equivalents, and an English equivalent or explanation, are given wherever applicable. Where no German or French is given, it may be assumed that no exact equivalent exists and that the Italian form is used in all languages.

214 Terms used to indicate TEMPO

ITALIAN FRENCH GERMAN ENGLISH

Lento Lent Lang sain Slow

Largo Large Breit Broad

Adagio (literally, "At ease," but usually means "Slow," sometimes with connotation of "drawn out")

Grave Lourd Schwer Heavy, Serious

Larghetto (diminutive of Largo; not so broad as Largo) *

E

Andante Allant Gehend Medium slow

(literally, "going" or "walking")

Moderato Modere Massig Moderate

D ] Allegretto (diminutive of Allegro; less fast than Allegro)

t ] Andantino (Musicians disagree on the meaning added to Andante by the diminutive suffix "-mo," some claiming that it means "less slow

Tj F than Andante," others pointing out that Andante means "going," rather than "slow," and that Andantino therefore signifies "less

M ^ going than Andante," i.e., even slower!)*

Allegro Anime, Vite Schnell Fast

(literally, "happy")

Wivace Vif Lebhaft Lively

'Presto Tres vite Sehr schnell, Very fast

Eilig

Vivacissimo (even livelier than Vivace)

Prestissimo (even faster than Presto)

-ino ) * n g enera l> the diminutive suffix, -ino or -etto, added to one of the l basic tempo indications, implies less of the quality of the original ~ etto ) term, i.e., weakens it.

issimo In general, the augmentative suffix, -issimo, added to one of the basic tempo indications, implies more of the quality of the original term, i.e., intensifies it.

non troppo pas trop nicht zu not too

(slow, fast, etc.)

"When Andantino, Adagietto, or Larghetto is used as the title of a composition, the diminutive ending often refers to the proportions of the piece, rather than to its tempo; e.g., Andantino then signifies "an Andante of small proportions."

FOREIGN TERMS USED IN MUSIC

215 Terms used to indicate CHANGE of TEMPO

157

piu

plus

mehr

(The prefatory adverb, piu, used with a tempo indication means "more," e.g., piu allegro means "more allegro," or "faster.")

meno

moins

weniger

(The prefatory adverb, meno, used with a tempo indication means "less," e.g., meno allegro means "less allegro," or "slower.")

piu mosso plus bewegter faster

mouvemejite (more movement)

meno mosso moins weniger bewegt slower

mouvemente (less movement)

a tempo au mouvement in Zeitmass in tempo

(used to restore the main tempo after a slowing down or speeding up)

Tempo Primo Premier Erstes First tempo

(Tempo I°.) mvement Zeitmass

(used to restore the first tempo when some other has Intervened I

L'istesso tempo Mime Dasselbe The same tempo

mouvement Zeitmass

(used to confirm the continuance of the same tempo when' the reader might imagine for some reason that it could change)

216 Terms used to indicate VOLUME of SOUND

The Italian words (and abbreviations) are ordinarily used in all languages:

forte (f) piano (%)) fortissimo fflfl pianissimo (ffp) mezzo forte (mf) mezzo piano (n*p)

loud soft

very loud very soft medium loud medium soft

Levels louder than jrtP are indicated by adding additional ^s:

JXf flXf

Levels softer than ffP are indicated by adding additional Jt s:

PPP , PPPP

2\7 Terms used to indicate CHANGE of VOLUME

ITALIAN

crescendo (cresc.)

decrescendo (decresc.

diminuendo (dim.)

ido J > \

FRENCH

en croissant

diminuer

GERMAN

wachsend

diminuieren, vermindern

ENGLISH

growing louder growing softer

The Italian words, crescendo, decrescendo, and diminuendo, and their abbreviations, are usually used in all languages, but the French and German equivalents given above are found occasionally. Very often, instead of the word crescendo, the sign " is used to indicate

"growing louder"; and instead of the words decrescendo or diminuendo, the sign ^^r^=^— is used to indicate "growing softer."

(used in all "begin the note loud,

languages) but drop it to soft

immediately"

(used in all "forced, accented"

languages)

fortepiano (fp )

sforzando, sforzato

pxu vievo

I Th

1 ar

These terms, already defined in connection with tempo, e also used in connection with volume.

FOREIGN TERMS USED IN MUSIC

159

218 Terms used to indicate SIMULTANEOUS REDUCTION of TEMPO and VOLUME

219 Qualifying terms used to indicate MOOD, DEGREE, IN-TENSITY, or STYLE

troppo

FOREIGN TERMS USED IN MUSIC

agreeably

APPENDIX THREE

The C-Clefs

220 On pages 71 and 72 it was explained that the G-clef is used for high voices and instruments and the F-clef for low voices and instruments. That is to say, from the whole series of lines which make up the Great Staff, the top five (marked with a clef sign on the G-line) are used separately whenever there would be no use for low notes, and the bottom five (marked with a clef sign on the F-line) may be used separately when there would be no use for high notes:

For high voices

and instruments (6)

r , (C)--«*'-

For low voices #p» _ gy

and instruments ZZZZ

:!

THE ALTO CLEF

221 Now, if one is dealing with voices or instruments which use chiefly the middle of the Great Staff - voices like the alto, for example, and instruments like the viola — neither of these five-line groups is perfectly suited, for such middle-of-the-road instruments would have no need for the very lowest and the very highest notes. Therefore, in writing for alto or viola, we may take the middle five lines of the Great Staff,

(C)

leaving off the top three lines of the upper staff, and the

bottom three lines of the lower staff. When these five lines are written separately there is no need to use a broken line for Middle C, the broken line having been introduced only because the original series of eleven lines was too much for the eye to grasp at once (see page 70). The clef which is used for these lines is a C-clef, that is, the line of Middle C is the one that is labeled with the symbolic letter. It looks like this:

Alto

cUf

m

111 This clef is called the alto clef because of its origins, although nowadays it is seldom used by alto singers, who ordinarily read in the more common treble (G) clef which the sopranos use. Its chief use today is for the viola, and even the viola sometimes reads from the treble clef when its music goes up very high.

THE TENOR CLEF

223 For tenor voices, it used to be customary to employ a slightly different form of this idea. Since the tenor sang notes a little lower than the alto's, although still in the middle region, only one line of the upper staff was retained along with three lines of the lower staff:

(C)~

The C-line (Middle C again) is marked with a C-clef symbol, as in the case of the alto clef, but here it comes out on the next higher line.

T»nor cUf

m

THE TENOR CLEF 165

224 In this position, the C clef is called the tenor clef, although today it is used less for the tenor voice than for the higher notes of the 'cello, bassoon, and trombone (occasionally the double-bass). For their lower notes, these instruments read in the bass (F) clef.

HYBRID CLEFS

225 As for tenor singers, the strange custom has grown up in recent years for them to pretend that they are reading in treble clef, like sopranos, but actually to produce the sounds an octave lower! Sometimes, to show that the tenor's treble clef is not a real one, it is printed as a double clef,

pnn-^

=h

or with an 8 (to show the octave lower) attached to it,

f

In other words, instead of indicating Middle C for a tenor voice by the use of the tenor clef, in this way, as you might expect :_m£\ , most publishers would indicate this

I IS ° =

note an octave higher than it is intended, or perhaps with one of the hybrid double-clefs:

im-#ni-g

n

COMPARISON OF CLEFS 226 By way of summary, let us compare how Middle C and other tones look in each clef:

THE C-CLEFS

NAMES OF OCTAVES

167

NAMES OF OCTAVES

227 In discussions in the theory of music, in order to distinguish one octave of a letter-name from another (a low C from a high C, for instance), the various octaves are assigned names or numbers. The following table should show you how this works:

228 The notes of the Three-lined and Four-lined Octaves involve so many leger lines that they are hard to read in their original notation. Therefore, they are sometimes written an

octave lower with an octave sign (8 ua ) above them to show their true meaning:

¥

Even with the aid of this method, as you will observe, a number of leger lines cannot be avoided.

229 For the extremely low notes of the Contra Octave and Sub-contra Octave, a similar method is used to avoid some of the leger lines:

— —**—o— ,~ ■_

^ 8V" bassa - - '

For the low octaves, this octave sign is written below the notes, and careful musicians usually write "8 va bassa" ("low octave") to make sure that there is no confusion with the octave sign for high notes.

230 Note that the letter-names in the Great Octave are written in capital letters, those of the Small Octave in small letters, those in the one-lined Octave with one "line" or "prime mark" after each letter, the Two-lined Octave with two lines after each, etc. In the Contra Octave, a line is used below and in front of the capital letter; and in the Sub-contra Octave, a double line is used in this position. Some writers use little index numbers instead of lines, so that instead of d" and e''', you may see d 2 and e 3 . Similarly they might use 2 A for the Sub-contra Octave instead of , A.

Identification of Notes in Section 87 ; Page 74

169

Identification of Notes in Section 104*, Page 85

The second Bb below

Middle C

The D below Middle C

The Fs below Middle C

The Ab below Middle C

The Bb below Middle C

The second At below

Middle C

The Ct below Middle C

The-DJt below Middle C

The Gt below Middle C

The second Ab below

Middle C

The second Gb below

Middle C

The second Ft below

Middle C

The second Eb below

Middle C

The Eb below Middle C

The second Ct below

Middle C

The Db below Middle C

The Gb below Middle C

The Ct immediately

above Middle C

(Cf. No. 6)

The D above Middle C

•For formal nomenclature of notes, according to the octa 1

which they appear, see Section 227, page 167

accent mark, 124 accidentals, 75-79, 81, 86-89,

125-127 alftne, 115-116 alia breve, 49 K. "All Through the Night," 56 alto clef, 163-164; see also

C-clef "America," 52, 95-100 articulation (symbols),

124-128 "AuClairdelaLune,"91 "Auld Lang Syne," 137 bar, 4

bar line, 4, 7,101-102 bass clef, 71-74,107;

see also F-clef beam, 21, 117-119, 128-130 beat, 1,26-27, 47-51, 101 "Blue Skies," 60 C-clef, 72 n., 163-165. See also

alto clef; tenor clef chironomy, 67 clef, 71-73,104, 163; tables,

166. See also C-clef;

F-clef; G-clef "Come Thou Almighty King,"

54 common time, 47 n. compound meter, 49-51, 58-59 cut time, 49 »., 53 D.C., 115-116 D.S., 115-116 da capo, 115-116 dalsegno, 115-116 dashes, 127 "Deck the Halls," 59 degree, 139; sec also interval dots (staccato), 124,127-128 dotted note, 18-21,33-37.

40-44,97-98,110 double bar, 4, 7 double-dotted note, 20-21 double flat, 79 n. double sharp, 79 //. "Doxology," 101, 138

"Drink to Me Only with

Thine Eyes," 58 duple meter, 29-31, 32-37,

42-44, 48-50 dynamic indications, 122-124,

158-159 dynamic level, 122-124 eighth-note, 8, 11-13,21,

117-118 F-clef, 71-74, 163; see also

bass clef fermata, 103 fine, see al fine first ending, 114-115 flat, 75-76, 84; see also

accidentals foreign-language terms,

26-27, 122-123, 155-161 frequency of vibration, 64-65 "Frere Jacques," 3, 8, 57 G-clef, 71-74, 163; see also

treble clef grace note, 121-122 great staff, 71, 163 half-note, 5-6, 49, 117-1 If half-step, 78 »., 139-149,

151-152 "Hark, the Herald Angels

Sing," 56 harmonic minor scale, 152 hold, 103 "Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord

God Almighty," 3. 7. 56 hook, 8-10, 87, 128-130 hybrid clefs, 165 interval, 78 >/.. 139, 148. "Iso half-step;

whole-step "Jingle Bells.'• -

107-114, 11C, 129-130 '•Joy to the World." 54 key, 134; $ee als<> tonality key center, L34; tti alto tonic key signature, 9 L04,

141. 143-147. L51-163 key Signature, tables. 160, 164

leger line, 74-75,167-168 major scale, 139-154; table of key signatures, 150

"Marine's Hymn, The," 115

measure, 4, 101-102. See also bar; meter; metric signature

melodic minor scale, 153

meter, 4, 28-61. See also compound meter; duple meter; metric signature; triple meter

metric signature, 28, 31, 47

metronome, 27-28

Middle C, 82

minor scales, 150-154; table of key signatures, 154

natural, 86-87

natural minor scale, 152

neumes, 67-68

notation, history, 66-71

note values, table, 10-11. See also eighth-note; sixteenth-note; subdivided beat; etc.

octave, 65-66,142, 167

octave sign, 168

"Oh, What a Beautiful Morning," 55

"Old Folks at Home," 58,116

"Old Hundred," see "Doxol-ogy"

"Onward, Christian Soldiers," 55

"Ophelia's Song" (in Hamlet), 152

ornaments, 120-122

"People Will Say We're in Love," 60

piano keyboard, 76-85,137

pitch, 1, 63-89

pulse, see beat

quarter-note, 6

quintolet, see quintuplet

quintuplet, 18

repeat sign, 113-114; see also repetitions

repetitions, 113-119

rests, 22-23

"Reuben and Rachel," 53

rhythm, 1-61

"Santa Lucia," 55

scale, 134, 138-154. See also

major scale; minor scale second ending, 115 sharp, 75-76, 84; see also

accidentals sixteenth-note, 9,13-14, 21,

117-119 sixty-fourth-note, 10 slur, 125-127,127-128,129 "Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,"

57 staff, 68-73 stem, 5, 87

step, 139; see also interval subdivided beat, 34, 36-37, 40,

50, 97-98 syllables, vocal music, 128-130 syncopation, 44-46 tempo, 25-28, 47-49 tempo indications, 26-28, 103,

156-157, 159 tenor clef, 164-165 text syllables, 128-130 thirty-second-note, 10, 118 "Three Blind Mice," 58-59 tie, 14-16, 19-21, 23, 41, 43-46,

125-127 time signature, see metric

signature tonality, 131-135 tonic, 133-134,138-140,142,

152-154 treble clef, 71-74,165; see also

G-clef tremolo, 118-119 trill, 117 triple meter, 29-31, 38-42,

47-51 triplet, 17,41,44,49-51 upbeat, 101, 104 vibrations, 65

vocal music, syllables, 128-130 volume, 158-159. See also

dynamic level; dynamic

indications whole-note, 4-5 whole-step, 78 n., 139-149 "Yankee Doodle," 52

About the Author

As Mr. Shanet explains in his Introduction, he taught the contents of this book to more than a thousand students when he was conductor of the symphony orchestra at Huntington, West Virginia. Previously, he had taught it to many others when he was a member of the Music Department at Hunter College in New York City.

For the past two years he has been Assistant Professor of Music at Columbia University and conductor of the University Orchestra. A native New Yorker, he received his undergraduate and graduate training at the same institution, and he received special training in conducting under such masters as Serge Koussevitzky, Fritz Stiedry and Rudolph Thomas, and in composition under Bohuslav Martinu and Arthur Honegger. He is also a cellist who has made many radio and concert appearances, especially in chamber music groups.

During the war, he served with the "Dixie" Division, and during 1950 he toured in the United States, Cuba, Europe, and Israel as assistant conductor to Serge Koussevitzky.

ABOUT THK Al'THOR

As Mr. Shanet explains in his Introduction, he taught the contents of this book to more than a thousand students when he was conductor of the symphony orchestra at Huntington, West Virginia. Previously, he had taught it to many others when he was a member of the Music Department at Hunter College in New York City.

For the past two years he has been Assistant Professor Of

Music at Columbia University and conductor of the University Orchestra. A native New Yorker, he received his undergraduate and graduate training at the same institution, and he received special training in conducting under BUCh masters as Serge Koussevitzky, Fritz Stiedry and Rudolph Thomas, and in composition under Bohuslav Martinu and Arthur Honegger. He is also a cellist who has made many radio and concert appearances, especially in chamber music groups.

During the war, he served with the 'I >ixi« " Division, and

during I960 he toured in the United states. Cuba. Europe,

and Israel as assistant conductor to Serge K Ky.