In this chapter, you will extend your understanding of the rational numbers, learn about irrational numbers, and recognize the real numbers as the set consisting of all the rational and irrational numbers. You will use rational approximations of irrational numbers to compare the size of irrational numbers, locate them approximately on a real number line, and approximate the value of irrational expressions.

Understanding Rational Numbers

(CCSS.Math.Content.8.NS.A.1)

A rational number is any number that can be expressed as ![]() , where p and q are integers and q is not zero. The rational numbers include zero and all the numbers that can be written as positive or negative fractions. They are the numbers you are familiar with from your previous work with numbers in arithmetic.

, where p and q are integers and q is not zero. The rational numbers include zero and all the numbers that can be written as positive or negative fractions. They are the numbers you are familiar with from your previous work with numbers in arithmetic.

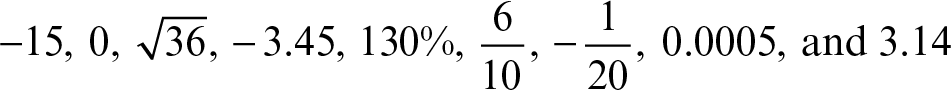

The rational numbers include whole numbers and integers. Here are examples.

The rational numbers include positive and negative fractions. Here are examples.

The rational numbers include positive and negative repeating and terminating decimals. (See below for a discussion on repeating and terminating decimals.) Here are examples.

The rational numbers include positive and negative percents. Here are examples.

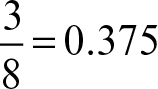

You obtain the equivalent decimal representation of a fraction, such as ![]() , by performing the indicated division. (Tip: Remember,

, by performing the indicated division. (Tip: Remember,  .) You divide the numerator by the denominator. Insert a decimal point in the numerator and zeros to the right of the decimal point to complete the division.

.) You divide the numerator by the denominator. Insert a decimal point in the numerator and zeros to the right of the decimal point to complete the division.

The fraction ![]() and the decimal 0.75 are different representations of the same rational number. They are both located at the same location on the number line.

and the decimal 0.75 are different representations of the same rational number. They are both located at the same location on the number line.

Tip: If the fraction is a negative number, perform the division without the negative sign, and then attach the negative sign to the decimal expansion. For example,  .

.

It is important you know the decimal expansion of a rational number either terminates in 0s or eventually repeats. In the case of ![]() , you need to insert only two zeros after the decimal point for the division to finally reach a zero remainder. Inserting additional zeros would lead to repeated 0s to the right of 0.75 (like this: 0.75000…). You say that the decimal expansion of

, you need to insert only two zeros after the decimal point for the division to finally reach a zero remainder. Inserting additional zeros would lead to repeated 0s to the right of 0.75 (like this: 0.75000…). You say that the decimal expansion of ![]() terminates in 0s.

terminates in 0s.

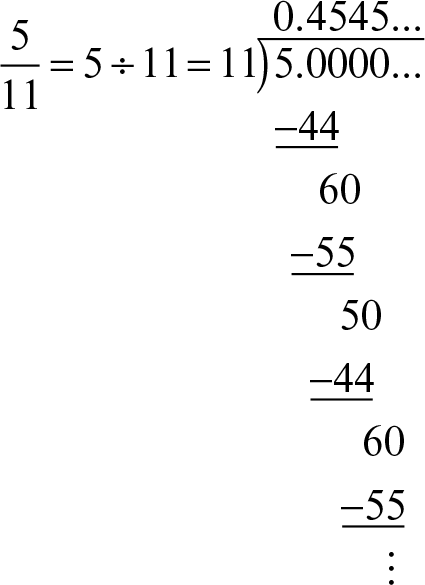

However, for some rational numbers, the decimal expansion keeps going, but in a block of one or more digits that repeats over and over again. The repeating digits are not all zero. Here is an example.

No matter how long you continue to add zeros and divide, 45 in the quotient continues to repeat withoutend. You put a bar over one block of the repeating digits to indicate the repetition; thus,  . You say

. You say ![]() has a repeating decimal expansion. It is incorrect to write

has a repeating decimal expansion. It is incorrect to write  . Still, when decimals repeat, they are usually rounded to a specified degree of accuracy. For instance,

. Still, when decimals repeat, they are usually rounded to a specified degree of accuracy. For instance,  when rounded to two decimalplaces.

when rounded to two decimalplaces.

Tip: Read the symbol ≈ as “is approximately equal to.”

Pretend you do not know 0.4545… is the decimal expansion of ![]() . How would you go about converting the repeating decimal expansion 0.4545… into its fractional form

. How would you go about converting the repeating decimal expansion 0.4545… into its fractional form  ? Here is the way to do it. (Tip: This procedure works for any repeating decimal expansion.)

? Here is the way to do it. (Tip: This procedure works for any repeating decimal expansion.)

Let x = 0.4545…. Do three steps. First, multiply both sides of the equation x = 0.4545… by 10r, where r is the number of digits in the repeating block of digits in the decimal expansion. Next, subtract the original equation from the new equation. Then divide both sides of the resulting equation by the coefficient of x.

Step 1. Multiply both sides of the equation x = 0.4545… by 102 = 100 (because two digits repeat).

Step 2. Subtract the original equation from the new equation.

Step 3. Solve for x by dividing both sides of the resulting equation by the coefficient of x.

Thus,  .

.

Tip: Notice when you multiply 0.4545… by 100, you can write the product as 45.4545…. You can do this because there are infinitely many 45s to the right of the decimal point, so you can write as many as you please.

Here is an additional example of the procedure.

Convert –3.666… to its equivalent fractional form.

Tip: If the number is negative, do the conversion without the negative sign, and then attach the negative sign to the fractional representation.

Let x = 3.666…

Step 1. Multiply both sides of the equation x = 3.666… by 101 = 10 (because one digit repeats).

Step 2. Subtract the original equation from the new equation.

Step 3. Solve for x by dividing both sides of the resulting equation by the coefficient of x.

Thus,  .

.

![]() Try These

Try These

- Fill in the blank(s).

- A rational number is any number that can be expressed as __________, where p and q are integers and q is not zero.

- The decimal expansion of a rational number either __________ in 0s or eventually __________.

- Write the decimal expansion for the rational number.

- Convert the decimal expansion to an equivalent fractional form.

- 0.666…

- 0.142857142857…

- 1.1818…

Solutions

Recognizing Rational and Irrational Numbers

(CCSS.Math.Content.8.NS.A.1)

Irrational numbers are numbers that cannot be written in the form ![]() , where p and q are integers and q is not zero. They have nonterminating, nonrepeating decimal expansions. An example of an irrational number is the positive number that multiplies by itself to give 2. This number is the principal square root of 2. Every positive number has two square roots: a positive square root and a negative square root. The positive square root is the principal square root. The square root symbol

, where p and q are integers and q is not zero. They have nonterminating, nonrepeating decimal expansions. An example of an irrational number is the positive number that multiplies by itself to give 2. This number is the principal square root of 2. Every positive number has two square roots: a positive square root and a negative square root. The positive square root is the principal square root. The square root symbol ![]() is used to show the principal square root. Thus, the principal square root of 2 is written like this:

is used to show the principal square root. Thus, the principal square root of 2 is written like this: ![]() . The other square root of 2 is

. The other square root of 2 is ![]() . It also is an irrational number.

. It also is an irrational number.

Tip: Zero has only one square root; namely, zero (which is a rational number).

You cannot express ![]() as

as ![]() , where p and q are integers (q ≠ 0), and you cannot express it precisely in decimal form. No matter how many decimal places you use, you can only approximate

, where p and q are integers (q ≠ 0), and you cannot express it precisely in decimal form. No matter how many decimal places you use, you can only approximate ![]() . If you use a calculator to find the square root of the number 2, the display will show a decimal approximation of

. If you use a calculator to find the square root of the number 2, the display will show a decimal approximation of ![]() . An approximation of

. An approximation of ![]() to nine decimal places is 1.414213562. You can check whether this is

to nine decimal places is 1.414213562. You can check whether this is ![]() by multiplying it by itself to see whether you get 2.

by multiplying it by itself to see whether you get 2.

1.414213562 · 1.414213562 = 1.999999999

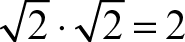

The number 1.999999999 is very close to 2, but it is not equal to 2. Only ![]() or

or ![]() will multiply by itself to give 2. Thus,

will multiply by itself to give 2. Thus,  and

and  .

.

Even though an exact value for ![]() cannot be determined,

cannot be determined, ![]() is a number that occurs frequently in the real world. For instance, architects, carpenters, and other builders encounter

is a number that occurs frequently in the real world. For instance, architects, carpenters, and other builders encounter ![]() when they measure the length of the diagonal of a square that has sides with lengths of one unit, as shown here.

when they measure the length of the diagonal of a square that has sides with lengths of one unit, as shown here.

The diagonal of such a square measures ![]() units.

units.

Tip: For most purposes, you can use 1.414 as an approximation for ![]() .

.

There are an infinite number of square roots that are irrational. Here are a few examples.

Another important irrational number is the number represented by the symbol π (pi). The number π also occurs frequently in the real world. For instance, π is the number you get when you divide the circumference of a circle by its diameter. The number π cannot be expressed as a fraction, nor can it be written as a terminating or repeating decimal. Here is an approximation of π to nine decimal places: 3.141592654.

Tip: There is no pattern to the digits of π. In this book, use the rational number 3.14 as an approximation for the irrational number π in problems involving π.

Not all square roots are irrational. For example, the principal square root of 25, denoted ![]() , is not irrational because

, is not irrational because ![]() , which is a rational number. The number 25 is a perfect square because its square root is rational. When you want to find the principal square root of a number, try to find a nonnegative number that multiplies by itself to give the number. You will find it helpful to memorize the following principal square roots.

, which is a rational number. The number 25 is a perfect square because its square root is rational. When you want to find the principal square root of a number, try to find a nonnegative number that multiplies by itself to give the number. You will find it helpful to memorize the following principal square roots.

Make yourself a set of flash cards or make matching cards for a game of “Memory.” For the Memory game, turn all the cards facedown. Turn up two cards at a time. If they match (for instance, ![]() and 12 are a match), remove the two cards; otherwise, turn them facedown again. Repeat until you have matched all the cards.

and 12 are a match), remove the two cards; otherwise, turn them facedown again. Repeat until you have matched all the cards.

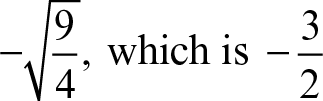

Here are examples of rational square roots.

Keep in mind, though, every positive number has two square roots. The two square roots are equal in absolute value, but opposite in sign. For instance, the two square roots of 25 are 5 and –5, with 5 being the principal square root. Still, the square root symbol ![]() always gives just one square root as the answer, and that square root is either positive or zero. Thus,

always gives just one square root as the answer, and that square root is either positive or zero. Thus, ![]() , not –5 or ±5 (read “plus or minus 5”). If you want ±5, then do this:

, not –5 or ±5 (read “plus or minus 5”). If you want ±5, then do this:  .

.

Tip: Recall that the absolute value of a specific number is just the value of the number with no sign attached.

- Fill in the blank(s).

- Irrational numbers are numbers that __________ (can, cannot) be written in the form

, where p and q are integers and q is not zero.

, where p and q are integers and q is not zero. - Irrational numbers have nonterminating, __________ decimal expansions.

- The square root symbol

is used to show a __________ square root, which is just one number.

is used to show a __________ square root, which is just one number. - Every positive number has __________ square roots.

- Zero has __________ square root(s).

- Irrational numbers are numbers that __________ (can, cannot) be written in the form

- Indicate whether the number is rational or irrational by writing “rational” or “irrational” as your answer.

- 62.75

- π

Solutions

-

- cannot

- nonrepeating

- principal

- two

- one

-

- irrational

- irrational

- rational

- irrational

- rational

- rational

- rational

- rational

- irrational

Approximating Irrational Numbers and Expressions

(CCSS.Math.Content.8.NS.A.2)

You cannot write an exact decimal representation of an irrational square root. However, you can approximate its value to a desired number of decimal places. Here is an example.

Approximate ![]() to the nearest hundredth.

to the nearest hundredth.

Step 1. Approximate ![]() to the nearest whole number.

to the nearest whole number.

Find two consecutive integers such that the square of the first integer is less than 40 and the square of the second integer is greater than 40. You know 6 × 6 = 36, which is less than 40, and 7 × 7 = 49, which is greater than 40. Thus,  . So, the approximate value of

. So, the approximate value of ![]() is between 6 and 7. It is closer to 6 because 40 is closer to 36 (4 units away) than it is to 49 (9 units away). To the nearest whole number,

is between 6 and 7. It is closer to 6 because 40 is closer to 36 (4 units away) than it is to 49 (9 units away). To the nearest whole number, ![]() is approximately 6.

is approximately 6.

Step 2. Approximate ![]() to the nearest tenth.

to the nearest tenth.

Consider that 49 and 36 are 13 units apart and 40 and 36 are 4 units apart. So, 40 is ![]() of the distance between 49 and 36. As a rough approximation,

of the distance between 49 and 36. As a rough approximation, ![]() is about

is about ![]() of the distance between 6 and 7. The distance between 6 and 7 is 1 unit. So,

of the distance between 6 and 7. The distance between 6 and 7 is 1 unit. So,  . This calculation leads to the guess that

. This calculation leads to the guess that ![]() is between 6.3 and 6.4. Square each of these numbers, 6.3 × 6.3 = 39.69 and 6.4 × 6.4 = 40.96. The value of

is between 6.3 and 6.4. Square each of these numbers, 6.3 × 6.3 = 39.69 and 6.4 × 6.4 = 40.96. The value of ![]() is closer to 6.3 than it is to 6.4 because 40 is closer to 36.69 (0.31 unit away) than it is to 40.96 (0.96 unit away). To the nearest tenth,

is closer to 6.3 than it is to 6.4 because 40 is closer to 36.69 (0.31 unit away) than it is to 40.96 (0.96 unit away). To the nearest tenth, ![]() is approximately 6.3.

is approximately 6.3.

Step 3. Approximate ![]() to the nearest hundredth.

to the nearest hundredth.

Consider that 40.96 and 39.69 are 1.27 units apart and 40 and 39.69 are 0.31 unit apart. So, 40 is ![]() of the distance between 40.96 and 39.69. As a rough approximation,

of the distance between 40.96 and 39.69. As a rough approximation, ![]() is about

is about ![]() of the distancebetween 6.3 and 6.4. The distance between 6.3 and 6.4 is 0.1 unit. So, to the nearest hundredth,

of the distancebetween 6.3 and 6.4. The distance between 6.3 and 6.4 is 0.1 unit. So, to the nearest hundredth,  . (Checking it, 6.32 × 6.32 = 39.9424, which is very close to 40.) On a number line, you would mark

. (Checking it, 6.32 × 6.32 = 39.9424, which is very close to 40.) On a number line, you would mark ![]() at approximately 6.32.

at approximately 6.32.

To approximate irrational expressions, approximate the irrational component and then evaluate.

Approximate π2 to the nearest tenth.

π2 ≈ (3.14)2 = 9.8596 ≈ 9.9

Approximate ![]() to the nearest hundredth.

to the nearest hundredth.

![]() Try These

Try These

- Approximate the irrational square root to the nearest tenth.

- Using the results from question 1, approximate the irrational expression to the nearest tenth.

Solutions

-

Step 1. Approximate

to the nearest whole number.

to the nearest whole number.Find two consecutive integers such that the square of the first integer is less than 5 and the square of the second integer is greater than 5. You know 2 × 2 = 4, which is less than 5, and 3 × 3 = 9, which is greater than 5. Thus,

. So, the approximate value of

. So, the approximate value of  is between 2 and 3. It is closer to 2 because 5 is closer to 4 (1 unit away) than it is to 9 (4 units away). To the nearest whole number,

is between 2 and 3. It is closer to 2 because 5 is closer to 4 (1 unit away) than it is to 9 (4 units away). To the nearest whole number,  is approximately 2.

is approximately 2.Step 2. Approximate

to the nearest tenth.

to the nearest tenth.Consider that 9 and 4 are 5 units apart and 5 and 4 are 1 unit apart. So, 5 is

of the distance between 9 and 4. As a rough approximation,

of the distance between 9 and 4. As a rough approximation,  is about

is about  of the distance between 2 and 3. The distance between 2 and 3 is 1 unit. So,

of the distance between 2 and 3. The distance between 2 and 3 is 1 unit. So,  . This calculation leads to the guess that

. This calculation leads to the guess that  is between 2.2 and 2.3. Square each of these numbers, 2.2 × 2.2 = 4.84 and 2.3 × 2.3 = 5.29. The value of

is between 2.2 and 2.3. Square each of these numbers, 2.2 × 2.2 = 4.84 and 2.3 × 2.3 = 5.29. The value of  is closer to 2.2 than it is to 2.3 because 5 is closer to 4.84 (0.16 unit away) than it is to 5.29 (0.29 unit away). To the nearest tenth,

is closer to 2.2 than it is to 2.3 because 5 is closer to 4.84 (0.16 unit away) than it is to 5.29 (0.29 unit away). To the nearest tenth,  is approximately 2.2.

is approximately 2.2.

Step 1. Approximate

to the nearest whole number.

to the nearest whole number.Find two consecutive integers such that the square of the first integer is less than 28 and the square of the second integer is greater than 28. You know 5 × 5 = 25, which is less than 28, and 6 × 6 = 36, which is greater than 28. Thus,

. So, the approximate value of

. So, the approximate value of  is between 5 and 6. It is closer to 5 because 28 is closer to 25 (3 units away) than it is to 36 (8 units away). To the nearest whole number,

is between 5 and 6. It is closer to 5 because 28 is closer to 25 (3 units away) than it is to 36 (8 units away). To the nearest whole number,  is approximately 5.

is approximately 5.Step 2. Approximate

to the nearest tenth.

to the nearest tenth.Consider that 36 and 25 are 11 units apart and 28 and 25 are 3 units apart. So, 28 is

of the distance between 36 and 25. As a rough approximation,

of the distance between 36 and 25. As a rough approximation,  is about

is about  of the distance between 5 and 6. The distance between 5 and 6 is 1 unit. So,

of the distance between 5 and 6. The distance between 5 and 6 is 1 unit. So,  . This calculation leads to theguess that

. This calculation leads to theguess that  is between 5.3 and 5.4. Square each of these numbers, 5.3 × 5.3 = 28.09 and 5.4 × 5.4 = 29.16. The value of

is between 5.3 and 5.4. Square each of these numbers, 5.3 × 5.3 = 28.09 and 5.4 × 5.4 = 29.16. The value of  is closer to 5.3 than it is to 6.4 because 28 is closer to 28.09 (0.09 unit away) than it is to 29.16 (1.16 units away). To the nearest tenth,

is closer to 5.3 than it is to 6.4 because 28 is closer to 28.09 (0.09 unit away) than it is to 29.16 (1.16 units away). To the nearest tenth,  is approximately 5.3.

is approximately 5.3.

Step 1. Approximate

to the nearest whole number.

to the nearest whole number.Find two consecutive integers such that the square of the first integer is less than 80 and the square of the second integer is greater than 80. You know 8 × 8 = 64, which is less than 80, and 9 × 9 = 81, which is greater than 80. Thus,

. So, the approximate value of

. So, the approximate value of  is between 8 and 9. It is closer to 9 because 80 is closer to 81 (1 unit away) than it is to 64 (16 units away). To the nearest whole number,

is between 8 and 9. It is closer to 9 because 80 is closer to 81 (1 unit away) than it is to 64 (16 units away). To the nearest whole number,  is approximately 9.

is approximately 9.Step 2. Approximate

to the nearest tenth.

to the nearest tenth.Consider that 81 and 64 are 17 units apart and 80 and 64 are 16 units apart. So, 80 is

of the distance between 81 and 64. As a rough approximation,

of the distance between 81 and 64. As a rough approximation,  is about

is about  of the distance between 8 and 9. The distance between 8 and 9 is 1 unit. So,

of the distance between 8 and 9. The distance between 8 and 9 is 1 unit. So,  . This calculation leads to theguess that

. This calculation leads to theguess that  is between 8.9 and 9.0. Square each of these numbers, 8.9 × 8.9 = 79.21 and 9.0 × 9.0 = 81.00. The value of

is between 8.9 and 9.0. Square each of these numbers, 8.9 × 8.9 = 79.21 and 9.0 × 9.0 = 81.00. The value of  is closer to 8.9 than it is to 9.0 because 80 is closer to 79.21 (0.79 unit away) than it is to 81.00 (1.00 unit away). To the nearest tenth,

is closer to 8.9 than it is to 9.0 because 80 is closer to 79.21 (0.79 unit away) than it is to 81.00 (1.00 unit away). To the nearest tenth,  is approximately 8.9.

is approximately 8.9.

-

Understanding the Real Numbers

(CCSS.Math.Content.8.NS.A.1, CCSS.Math.Content.8.NS.A.2)

The real numbers are made up of all the rational numbers and all the irrational numbers. You can show real numbers on a number line. Every point on the real number line corresponds to a real number, and every real number corresponds to a point on the real number line. Here are examples.

Comparing Real Numbers

When comparing two real numbers, think of their relative locations on the number line. If the numbers have the same location, they are equal. If they don’t, they are unequal. Then, the number that is farther to the right is the greater number. For example,  because

because ![]() lies to the right of –4.5 on the number line.

lies to the right of –4.5 on the number line.

Here are some tips on handling situations that might occur when you are comparing and ordering real numbers:

If negative numbers are involved, they will be less than all the positive numbers and 0.

If percents are involved, change the percents to decimals.

If the problem contains exponential expressions, evaluate them before making comparisons.

If you have square roots that are rational numbers, find the square roots before making comparisons.

If you have irrational square roots, approximate the square roots before comparing them to other numbers.

Here is an example.

Order the list of numbers from least to greatest.

You do not have to proceed in the order the numbers are listed. Start with 32, 4.39, –4, and ![]() . Clearly, –4 is less than all the other numbers. Evaluate 32 to obtain 9, and write

. Clearly, –4 is less than all the other numbers. Evaluate 32 to obtain 9, and write ![]() as 4.50. The order from least togreatest for these four numbers is –4, 4.39, 4.50, 9. Next, approximate

as 4.50. The order from least togreatest for these four numbers is –4, 4.39, 4.50, 9. Next, approximate ![]() to be between 6 and 7, because

to be between 6 and 7, because  . So

. So ![]() lies between 4.50 and 9 in the list. At this point, your ordered list is –4, 4.39, 4.50,

lies between 4.50 and 9 in the list. At this point, your ordered list is –4, 4.39, 4.50, ![]() , 9. Substitute in your original numbers to get your final answer: –4, 4.39,

, 9. Substitute in your original numbers to get your final answer: –4, 4.39, ![]() ,

, ![]() , 32.

, 32.

Tip: When you’re working with only real numbers, don’t try to find square roots of negative numbers because not one real number will multiply by itself to give a negative number. For instance,  . No real number multiplies by itself to give –25.

. No real number multiplies by itself to give –25.

![]() Try These

Try These

- Fill in the blank(s).

- A real number is any __________ or __________ number.

- Every __________ on the real number line corresponds to a real number, and every real number corresponds to a __________ on the real number line.

- No real number will multiply by itself to give a __________ number.

- Which numbers are rational?

- Which numbers are irrational?

- Which numbers are real numbers?

- Order the list of numbers from least to greatest.

Solutions

-

- rational; irrational

- point; point

- negative

Evaluate

to obtain –6, which is less than –5. Evaluate

to obtain –6, which is less than –5. Evaluate  to obtain

to obtain  , and write

, and write  as 1.50. Approximate

as 1.50. Approximate  as lying between 2 and 3 because

as lying between 2 and 3 because  . At this point, the orderedlist is –6, –5, 0.25, 1.25, 1.50,

. At this point, the orderedlist is –6, –5, 0.25, 1.25, 1.50,  . Substituting in the original numbers gives the final answer:

. Substituting in the original numbers gives the final answer:  , –5,

, –5,  , 1.25,

, 1.25,  ,

,  .

.

Computing with Real Numbers

The rules for computing with real numbers are the same as the rules you already know for computing with rational numbers. You do the computations by using the absolute values of the numbers and then assigning the correct sign to the result. The absolute value of a real number is its distance from 0 on the real number line. The absolute value is always positive or zero.

For sums and differences of real numbers, use the following rules.

Rule 1: The sum of 0 and any number is the number.

Rule 2: The sum of a number and its opposite is 0.

Rule 3: To add two nonzero numbers that have the same sign, add their absolute values and give the sum their common sign.

Rule 4: To add two nonzero numbers that have opposite signs, subtract the lesser absolute value from the greater absolute value and give the result the sign of the number with the greater absolute value.

Rule 5: To subtract one number from another, add the opposite of the second number to the first.

For products and quotients of real numbers, use the following rules.

Rule 1: Zero times any number is 0.

Rule 2: To multiply two nonzero numbers that have the same sign, multiply their absolute values and make the product positive.

Rule 3: To multiply two nonzero numbers that have opposite signs, multiply their absolute values and make the product negative.

Rule 4: When 0 is one of the factors, the product is always 0; otherwise, products with an even number of negative factors are positive, whereas those with an odd number of negative factors are negative.

Rule 5: To divide by a nonzero number, follow the same rules for the signs as for multiplication, except divide the absolute values of the numbers instead of multiplying.

Rule 6: The quotient is 0 when the dividend is 0 and the divisor is a nonzero number.

Rule 7: The quotient is undefined when the divisor is 0.

![]() Try These

Try These

- Fill in the blank(s).

- The sum of __________ and any number is the number.

- The sum of a number and its opposite is __________.

- Zero times any number is __________.

- Products with a(n) __________ number of negative factors are positive, whereas those with a(n) __________ number of negative factors are negative.

- The quotient is __________ when the dividend is 0 and the divisor is a nonzero number. For example,

is __________.

is __________. - The quotient is __________ when the divisor is 0. For example,

is __________ and

is __________ and  is __________.

is __________.

- Find the sum or difference as indicated.

- –36 + 20

- –105.64 – 235

- 55 – 100

- –58.99 – 0.01

- Find the product or quotient as indicated.

- (–7)(–20)

- (105.34)(–238)

- (7.8)(9.1)(0)(–3.4)(125.9)

- (2)(–1)(–3)(20)(–10)

- (2)(–1)(3)(20)(–10)

Solutions

-

- 0

- 0

- 0

- even; odd

- 0; 0

- undefined; undefined; undefined

-

- –36 + 20 = –16

- –105.64 – 235 = –340.64

- 55 – 100 = –45

- –58.99 – 0.01 = –59.00

-

- (–7)(–20) = 140

- (105.34)(–238) = –25,070.92

- (7.8)(9.1)(0)(–3.4)(125.9) = 0

- (2)(–1)(–3)(20)(–10) = –1,200

- (2)(–1)(3)(20)(–10) = 1,200